Chapter Eleven

ALIVENESS & AFFECT: ALTERNATE ART & ANATOMIES

STELARC

PREFACE

1. MACHINE ART

Increasingly the potency of traditional media that artists use and the imagination of artists will be exhausted. It will be in the realm of AI (Artificial Intelligence) and AL (Artificial Life) that surprising aesthetic artifacts will be engineered. Unexpected outcomes that expose and extend what it means to be human. Art needs to be automated. Machines are what keep us fit, and accelerate people from one place to another. Instruments extend our sensory experience. Televisual media and the Internet globally monitor the world and stream information and images that we consider and consume. Machines are what keep us alive and that hasten our death. People no longer die a biological death. They die of accidents caused by technology, and they die when their life-support systems are switched off. The body’s aliveness and its affect are increasingly generated by machines. Art needs to be produced by machines. The sooner machines make art, the sooner people can focus on doing the important things in life. Art is too painful, time-consuming, and uses too many of our resources.

2. BIOART

Art is increasingly exhibiting qualities of aliveness in its responsiveness and interactivity. And with Bio-Art and Bio-Printing, living cells are now used in artistic expression as well as in medical applications. Living cells are molded into lumps of living tissue with biodegradable scaffolds, and with Organ Printing we can now print not only with cartridges of colored inks but with cartridges of living cells. Only when we can bio-print or stem cell grow, caressing a lump of terratoma-like living tissue that is slimy, that is throbbing, that quivers to the touch will we have a potent object to interrogate what it is to be alive, what it means to be a body, and what it means to be human. And with stem cell growing of organs and with Organ Printing there will be an abundance of organs. It will no longer be a time of Bodies Without Organs but rather of Organs Awaiting Bodies, OF ORGANS WITHOUT BODIES.

3. THE AGE OF CIRCULATING FLESH

In this age of gene mapping, body hacking, gender reassignment, neural implants, and prosthetic augmentation, what a body is and how a body operates has become problematic. Meat, metal, and code mesh into unexpected hybrid systems. The monstrous is no longer the alien other. We live in an age of circulating flesh. Body fluids and body parts have been preserved and are commodified. The blood flowing through my body today may be flowing in your body tomorrow. Organs are extracted from one body and are implanted into another body. Ova that have been harvested can be fertilized by sperm that was once frozen. Limbs that are amputated from a dead body can be reattached and reanimated on a living body. Faces can be exchanged. A face from a cadaver stitched to the skull of the recipient becomes a THIRD FACE, no longer resembling the face of the donor. A more robust and reliable hydraulic heart circulates the blood continuously, without pulsing. In the near future, you might place your head against your loved one’s chest. He may be warm to the touch, he may be breathing—but there will not be a heartbeat. We can preserve a cadaver indefinitely with plastination, while we can simultaneously sustain a comatose body on life-support systems. Dead bodies need not decompose, and near dead bodies need not die. THE BRAIN DEAD HAVE BEATING HEARTS. The brain dead have beating hearts.

4. CYBORG AND CHIMERIC CONSTRUCTS

We are increasingly expected to perform with Mixed & Augmented Realities as hybrid and chimeric constructs. We function as biological bodies but often are augmented and accelerated by instruments and machines. And we increasingly need to manage data streams in virtual systems. The Manga constructs of bodies being massively augmented by exoskeletons and the Medical constructs of traumatised bodies with replacement limbs and organs and the Military model of amplified and enhanced bodies are not the only possibilities. FRACTAL FLESH of bodies and bits of bodies spatially separated but electronically connected with the Internet as an external nervous system means the body itself does not change but its connectivity allows it a communication and collaboration that was not possible previously. As well as Fractal Flesh we are in an age of PHANTOM FLESH. With the increasing proliferation of haptics on the Internet we will be able to generate more potent physical experiences of the remote other. To generate phantom limbs and phantom bodies coupled to the local body.

5. ATOMS-UP ARCHITECTURE & INVERSE EMBODIMENT

Engineering structures at a nano-scale means being able to engineer architectural structures inside the body, atoms-up. It will no longer be meaningful to distinguish between the synthetic and genetic tissue of the body. Redesigning the body atoms-up, inside-out becomes an inverse embodiment. A means by which we can aesthetically interrogate the evolutionary architecture of the body. As technology becomes micro-miniaturized in scale and biocompatible in substance, it will safely inhabit the cellular and organ spaces of the body. Perhaps all technology of the future will be invisible because it will be inside the body. And perhaps art will no longer merely inhabit public spaces but rather will be inserted into private physiological spaces.

PERFORMANCES & PROJECTS

OBSOLETE, EMPTY, ABSENT, AND INVOLUNTARY: WHAT A BODY IS AND HOW A BODY OPERATES

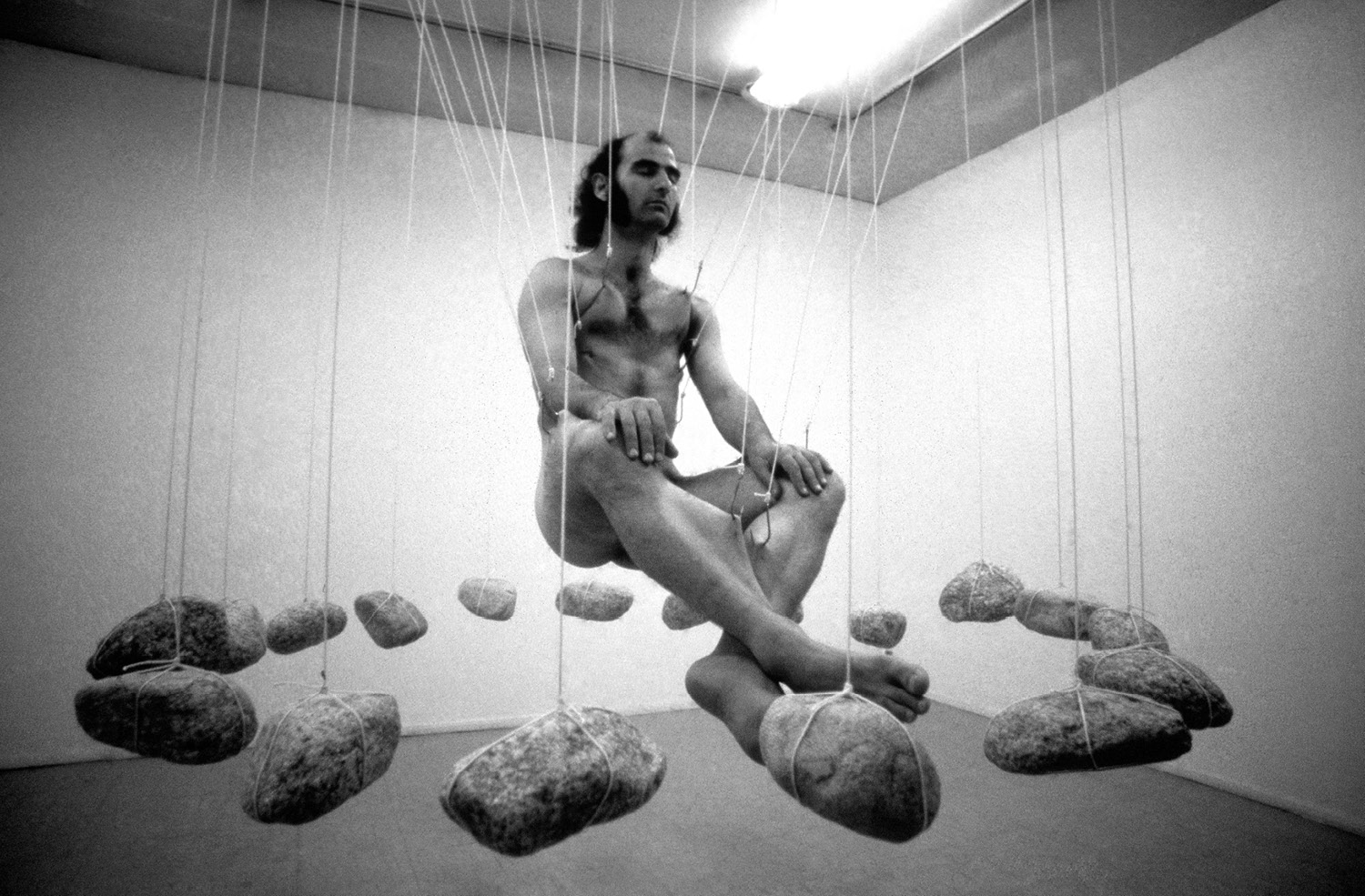

Suspended from its skin, the body becomes a gravitational landscape. The body is sitting and swaying, generating random oscillations in the surrounding ring of rocks that counterbalance the body’s weight. The performance was terminated when the telephone rang in the gallery. What becomes apparent is that the body is profoundly obsolete. It is outperformed by the precision, power, and speed of its technologies. It is absent from its own agency, and performs mostly involuntarily, its behavior determined primarily by the world it inhabits. The more and more performances this body does the less and less it experiences a mind of its own, nor any mind at all in the traditional metaphysical sense. The body neither has the cortical capacity nor the sensory apparatus to process and subjectively experience the extended terrain of information and images it must now interface with. It’s time to consider redesigning the human body. What it means to be human is perhaps not remaining human at all. Nor remaining as a species.

Figure 11.1. SITTING / SWAYING: EVENT FOR ROCK SUSPENSION- TAMURA GALLERY, TOKYO 11 MAY 1980.

PHOTOGRAPH- KEISUKE OKI.

Used by permission of the artist.

KEEPING YOUR TWO EYES ON WHAT YOUR THREE HANDS ARE DOING: AUGMENTING AND EXTENDING THE BODY’S CAPABILITIES

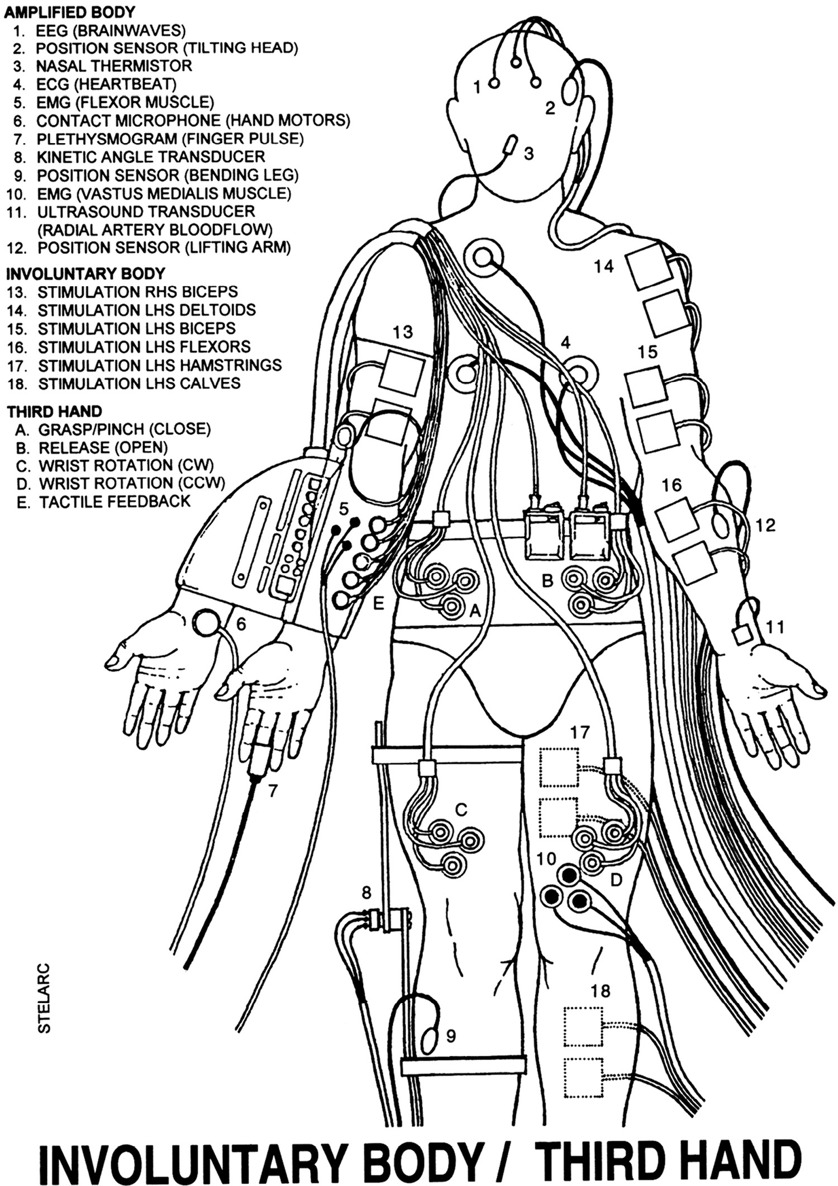

The Third Hand is an EMG actuated mechanism with a pinch-release, grasp-release and 300-degree rotation (CW & CCW). It has a tactile feedback system at its fingertips for a rudimentary sense of touch, which was felt on the forearm via vibrating sensors. The intent was to have the extra hand attached on a daily basis, using it for mundane tasks. But with skin irritation from the EMG electrodes and the weight of the hand system more than expected it was used specifically for performance. Initially the hand was merely a visual attachment in the performances. But then there were experiments in drawing and writing. Only two words were learned—Evolution and Decadence, as they are nine-letter words. Because of the spacing of the three hands you had to learn to write every third letter: E, L, and I; V, U, and O; O, T, and N. And because this performance occurred on a sheet of glass between the body and the audience I had to learn to write it back to front. The prosthesis is not a sign of lack but a symptom of excess. As technology becomes micro-miniaturized and biocompatible both in scale and substance, technology becomes a component, no longer a container of the body. Technology can be attached and safely inserted inside the body. The body over millions of years of its evolution has developed an immunological response to harmful microorganisms. It has no immunological response to technology, if that technology is small enough, sterile, and of biocompatible materials like stainless steel, gold, and medical-grade polymers.

Figure 11.2. HANDSWRITING: WRITING ONE WORD SIMULTANEOUSLY WITH THREE HANDS- MAKI GALLERY TOKYO, 1982.

PHOTOGRAPH- KEISUKE OKI.

Used by permission of the artist.

RE-WIRING THE HUMAN BODY: EXTERNAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

The THIRD HAND performances featured amplified body signals and sounds. The performance began when the body was switched on, and the performance was terminated when the body was switched off. Brainwaves, heartbeat, muscles, and bloodflow were monitored and preamplified with electrodes and transducers. The amplified sounds were partly physically controlled and partly the result of the fatigue during the performance. Blinking and contracting limb muscles generated a cacophony of percussive and white noise sounds. Constricting the radial artery at the wrist interrupted the whooshing blood flow sound. Varying breathing rate modulated the heartbeat rhythm and to a lesser extent the brainwaves. This was both an amplified and involuntary body with a computer-controlled muscle stimulation system generating preprogrammed movements of the limbs. For another Third Hand performance, titled PARASITE: EVENT FOR INVADED AND INVOLUNTARY BODY, a customized search engine was constructed that scans, selects, and displays images to the body—which functions in an interactive video field. Analyses of the JPEG files provide data that is mapped to the body via the muscle stimulation system. There is optical and electrical input into the body. The images that you see are the images that move you. The system electronically extends the body’s optical and operational parameters beyond its cyborg augmentation of its Third Hand and other peripheral devices. The prosthesis of the THIRD HAND is counterpointed by the prosthesis of the search engine software code. Plugged in, the body becomes a parasite sustained by an extended, external, and virtual nervous system. ALIEN AFFECT.

Figure 11.3. INVOLUNTARY BODY / THIRD HAND- YOKOHAMA, MELBOURNE 1990.

DIAGRAM- STELARC.

Used by permission of the artist.

ART NOT FOR A PUBLIC SPACE BUT RATHER FOR A PRIVATE PHYSIOLOGICAL SPACE

As surface, skin was once the beginning of the world and simultaneously the boundary of the self. But now stretched, pierced, and penetrated by technology, the skin is no longer the smooth and sensuous surface of a site for inscription or a screen for projection. Skin no longer signifies closure. The rupture of surface and skin means the erasure of inner and outer. An artwork has been inserted inside the body. The STOMACH SCULPTURE—constructed for the Fifth Australian Sculpture Triennale in Melbourne, whose theme was site-specific work—was inserted 40cm into the stomach cavity. Not as a prosthetic implant but as an aesthetic addition. The body is experienced as hollow with no meaningful distinctions between public, private, and physiological spaces. The hollow body becomes a host, not for a self but simply for a sculpture. As interface, the skin is obsolete. The significance of the cyber may well reside in the act of the body shedding its skin. Subjectively, the body experiences itself as a more extruded system, rather than an enclosed structure. The self becomes situated beyond the skin. It is partly through this extrusion that the body becomes empty. But this emptiness is not through a lack but from the extrusion and extension of its capabilities, its new sensory antennae, and its increasingly remote functioning.

Figure 11.4. STOMACH SCULPTURE- FIFTH AUSTRALIAN SCULPTURE TRIENNALE, NGV, MELBOURNE 1993.

PHOTOGRAPH- ANTHONY FIGALLO.

Used by permission of the artist.

INSECT ARCHITECTURE

EXOSKELETON is a six-legged, pneumatically powered walking machine. With either ripple or tripod gait it moves forward, backward, sideways, and turns on the spot. It can also squat and lift by splaying or contracting its legs. The body is positioned on a turntable, enabling it to rotate about its axis. It has an exoskeleton on its upper body and arms. The left arm is an extended arm with pneumatic manipulator having 11 degrees of freedom. It is human-like in form but with additional functions. The fingers open and close, becoming multiple grippers. There is individual flexion of the fingers, with thumb and wrist rotation. The body actuates the walking machine by moving its arms. Different gestures select different machine movements—a translation of arm to leg motions. The body’s arms guide the choreography of the locomotor’s movements and thus compose the cacophony of pneumatic, mechanical, and sensor modulated sounds. An alternate approach was taken with the MUSCLE MACHINE with the use of fluidic rubber muscle actuators eliminating problems of friction and fatigue that were a problem in the previous mechanical system of the Hexapod robot. The rubber muscles contract when inflated and extend when exhausted. This results in a more reliable and robust engineering design. The body stands on the ground within the chassis of the machine, which incorporates a lower-body exoskeleton connecting it to the robot. Encoders on the hip joints provide the data that allows the human controller to move and direct the machine as well as vary the speed at which it travels. Lifting one leg lifts the three alternate machine legs and swings them forward. By turning its torso, the body makes the machine walk in the direction it is facing. Thus the interface and interaction is more direct physical coupling, allowing an intuitive human-machine choreography. The walking system, with attached accelerometer sensors, generates data that is converted to sounds that augment the acoustical pneumatics and machine mechanism operation. The six-legged robot both extends the body and transforms its bipedal gait into a six-legged insect-like movement. Compared with Exoskeleton, the appearance and movement of the machine legs are both limb-like and wing-like in motion.

Figure 11.5. EXOSKELETON- CANKARJEV DOM, LJUBLJANA 2003.

PHOTOGRAPH- IGOR SKAFAR.

Used by permission of the artist.

STRETCHED SKIN

The STRETCHED SKIN image was printed on three panels to create a composite 4 m x 3 m color photographic installation. It was not exhibited on the wall but rather 40 cm above the floor, supported from below. Lit from above in the gallery space it became a flayed, flattened, and floating face. A landscape of stretched skin.

Figure 11.6. STRETCHED SKIN- SCOTT LIVESEY GALLERIES, MELBOURNE 2010.

PHOTOGRAPH- GRAHAM BARING.

Used by permission of the artist.

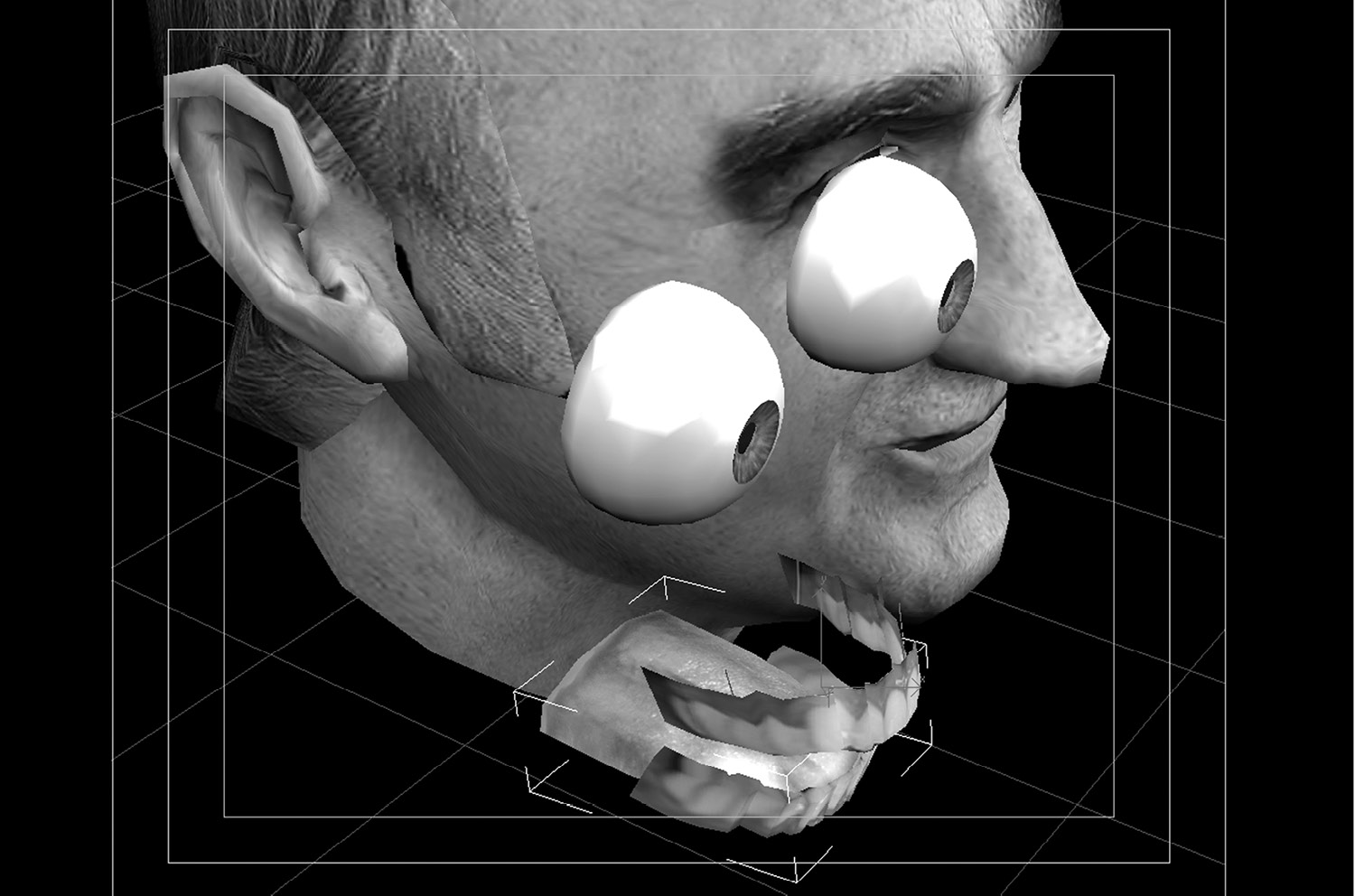

A PROSTHETIC HEAD

The aim was to construct an automated, animated, and reasonably informed talking head. The PROSTHETIC HEAD is an embodied conversational agent, which, coupled to a human head, is capable of some interesting verbal exchanges. It is a 3,000-polygon mesh wrapped with a skin that makes it somewhat resemble the artist. Its eyeballs, tongue, and teeth are separate moving components in the 3D model. There are enough morph targets for it to be able to speak all the phoneme sounds. The PROSTHETIC HEAD is ordinarily projected as a five-meter-high installation, in its own cuboid space, in its own headspace. The Head becomes a bodily presence. When you approach the keyboard it turns, opens its eyes, and initiates the conversation. It has an extensive database with a conversational strategy and real-time lip-synching. When user asks it a question it scans its database, searching for an appropriate response and, in real time, lip-synchs the spoken answer. As well as speaking, the Head makes song-like sounds and generates its own poems, which are different each time it is asked to recite one. As its database increases and the Head becomes more informed and less predictable, the artist will no longer be able to take full responsibility for what his Head says—although, at present, the Head is only as intelligent as the person interrogating it. The Prosthetic Head has been the research platform for the five-year THINKING HEAD project funded by an Australian Research Council grant to create a more intelligent, responsive, and seductive artificial agent. With the ARTICULATED HEAD, a more sculptural embodiment has been developed by mounting an LCD screen on the end of a 6-degree-of-freedom industrial robot arm. This explores sensory-motor intelligence, and an attention model has been developed by Christian Kroos. It will better test our sound location and vision tracking capabilities. Recently another iteration of the embodied conversational agent has been the FLOATING HEAD. This was a collaboration in Montreal with NXI Gestatio (Nicolas Reeves and David St. Ange) and MARCS at UWS. The SWARMING HEADS are a cluster of small wheeled robots with LCD screens mounted on their chassis, displaying the Prosthetic Head. Each robot has an attention model. With a repertoire of individual behavior, they will eventually exhibit interactive flocking and predator and prey behavior. Kinect sensors mounted on the front of each robot allow people to interact with them through arm gestures.

Figure 11.7. PROSTHETIC HEAD- SAN FRANCISCO, MELBOURNE 2002.

3D MODEL- BARRETT FOX.

Used by permission of the artist.

DIGITAL TRANSPLANT / THIRD FACE

The PARTIAL HEAD is a composite hominid-human face. After the artist’s face and a hominid skull were scanned, a digital transplant was done. The result was a THIRD FACE. The data was used to print a thermal plastic scaffold using a 3D printer. The scaffold was seeded with living cells and was placed in a custom-engineered bioreactor and life-support system. The face became contaminated within a week and the nutrients were drained, preserving the face in formaldehyde for the duration of the exhibition. The aim had been to grow a layer of living skin over a scaffold that was part hominid, part human in appearance. Whereas the PROSTHETIC HEAD is a digital portrait of the artist, the PARTIAL HEAD is a tissue-engineered portrait, and the WALKING HEAD (a six-legged robot with a human head displayed on its chassis) is a robot portrait of the artist.

Figure 11.8. PARTIAL HEAD- HEIDE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, MELBOURNE 2006.

3D MODEL- VINCENT WAN.

Used by permission of the artist.

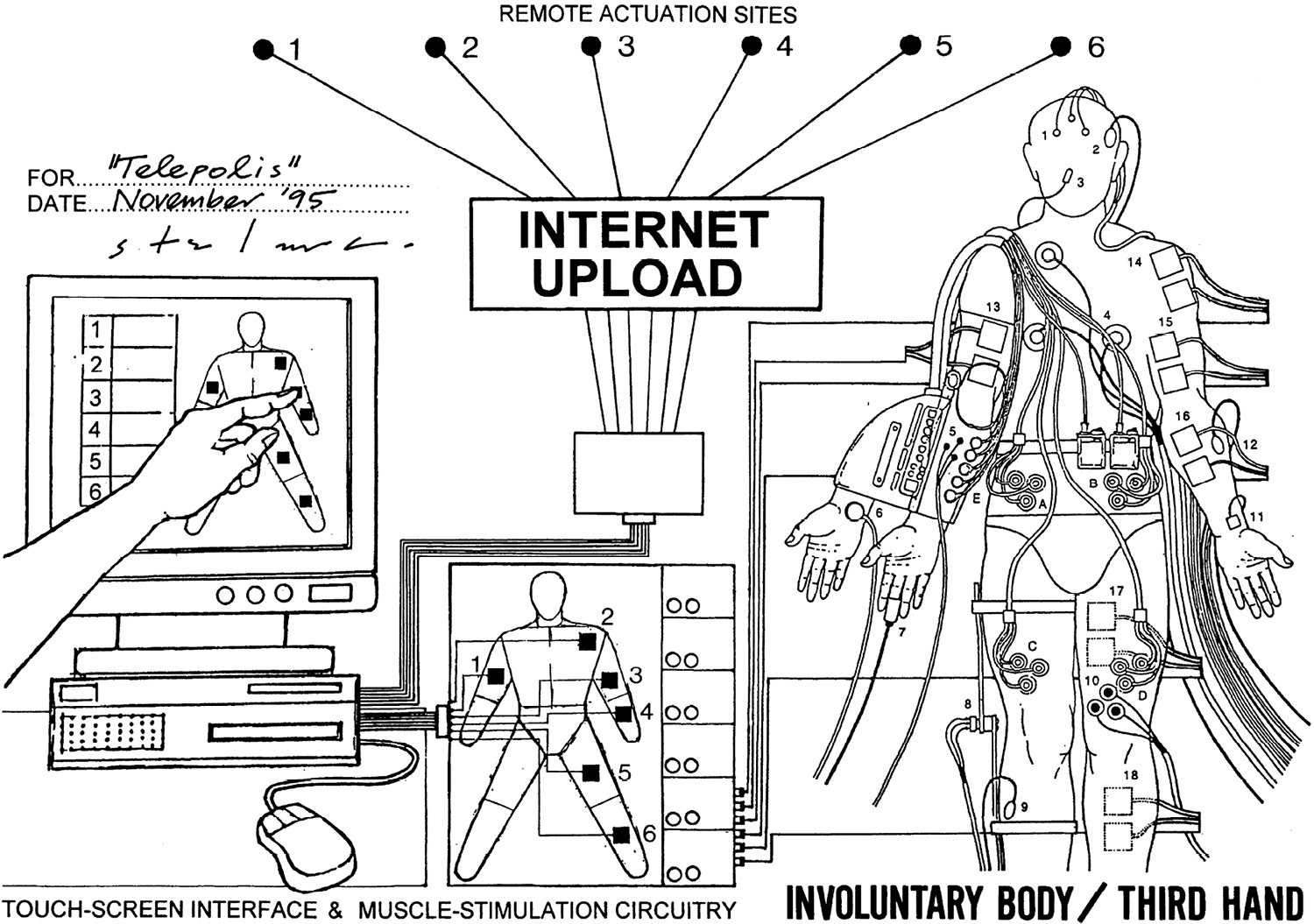

FRACTAL FLESH: REMOTELY ACCESSING AND ACTUATING A BODY BY PEOPLE IN OTHER PLACES

A touch-screen interface enabled people in the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the Media Lab in Helsinki, and the Doors of Perception Conference in Amsterdam to remotely access and remotely choreograph the body in Luxembourg. The touch-screen muscle stimulation system delivered 15–50 volts to the arm and leg muscles of the body. This performance was for two days, six hours a day continuously. While the artist was able to see the face of the person who was programming him, the programmers saw their remote choreography on large screens at each location. From the point of view of the users, they could project their physical presence to a body in another place. For the artist, the body becomes a host for the desires of remote agents. The body becomes simultaneously a possessed and performing body. When prompted to move involuntarily on its left side, it improvises with its Third Hand on the right side as a counterpoint. FRACTAL FLESH is not about a fragmented body but a multiplicity of bodies and parts of bodies prompting and remotely guiding each other. This is not about master-slave control mechanisms but feedback-loops of alternate awareness, agency and of split physiology. This physically split body may have one arm gesturing involuntarily (remotely actuated by an unknown agent), while the other arm is enhanced by an exoskeleton prosthesis to perform with exquisite skill and with extreme speed—a body capable of incorporating movement that from moment to moment would be a pure machinic motion performed with neither memory nor desire.

Figure 11.9. FRACTAL FLESH- TELEPOLIS, LUXEMBOURG 1995.

DIAGRAM- STELARC.

Used by permission of the artist.

SPLIT BODY: VOLTAGE-IN / VOLTAGE-OUT

We no longer function “all here” in this body nor “all there” in that body but “partly here” sometimes and “partly there” other times. Awareness slips and slides between spaces and situations. Imagine the consequences and advantages of being a SPLIT BODY with voltage-in manifesting the behavior of a remote agent and voltage-out actuating peripheral devices. This would be a more complex and interesting body, not simply a single entity with one agency but one that would be a construct of multiple and remote agents. Subjectively, the body experiences itself as more an EXTRUDED SYSTEM rather than as an enclosed structure. The self becomes situated beyond the skin, and the body is emptied. But this emptiness is not an emptiness of lack but rather a radical emptiness and absence through excess. An emptiness and absence from the extrusion and extension of its capabilities, its augmented sensory antennae, and its increasingly remote functioning. What becomes important is not merely the body’s identity but its connectivity, not its mobility or location but its interface. The body acts with indifference, an indifference that allows something other to occur, that allows an unfolding, in its own time and with its own rhythm.

Figure 11.10. SPLIT BODY: VOLTAGE-IN / VOLTAGE-OUT- GALERIE KAPELICA, LJUBLJANA 1996.

PHOTOGRAPHER- IGOR ANDJELIC.

Used by permission of the artist.

LIQUID BODY—BLENDED BIOMATERIAL

BLENDER, a more recent project exhibited in 2006 and in collaboration with another artist, Nina Sellars, involved undergoing surgical procedures to extract biomaterial from each artist’s body—from Stelarc’s torso and Nina’s limbs. The biomaterial was autoclaved for sterilization and the Blender vessel disinfected and hermetically sealed. Contents of the Blender vessel included subcutaneous fat, saline solution, local anaesthetic, adrenalin, O+ blood, sodium bicarbonate, peripheral nerves, and connective tissue. The machine installation was constructed of stainless steel, aluminum, and acrylic—supported and made operational by four bottles of compressed air. The idea was that a machine installation would host and blend the biomaterials for the duration of the exhibition. The biomaterial was aerated and blended once every five minutes, creating an automated choreography of bubbling and blending sounds that were amplified. This was a machine installation hosting a liquid body composed of biomaterial from two artists’ bodies. It was the inverse of the STOMACH SCULPTURE, where a soft and wet internal body space was the host for a machine choreography.

Figure 11.11. BLENDER- STELARC & NINA SELLARS- TEKNIKUNST, MEAT MARKET PROJECT SPACE, MELBOURNE 2007.

PHOTOGRAPH- STELARC.

Used by permission of the artist.

EXTRA EAR / REMOTE EYES

An extra ear is presently being constructed on my forearm: a left ear on a left arm, an ear that not only hears but also transmits. A facial feature has been replicated, relocated, and will now be rewired for alternate capabilities. Excess skin was created with an implanted expander in the forearm. By injecting saline solution into a subcutaneous port, the kidney-shaped silicon implant stretched the skin, forming a pocket of excess skin that could be used in surgically constructing the ear. A second surgery inserted a Medpor scaffold with the skin being suctioned over it. Tissue cells grow into the porous scaffold, fusing it to the skin and fixing it in place. At present it is only a relief of an ear. Further surgery is needed to lift the helix to construct an ear flap, and a soft ear lobe needs to be grown with the artist’s own adult stem cells. These would be replicated in vitro and then reinjected with growth hormones to produce the soft tissue. An additional surgical procedure will reimplant a miniature microphone that, connected to a wireless transmitter, will Internet-enable the ear in any Wi-Fi hotspot, making the ear a remote listening device for people in other places. This additional and enabled EAR ON ARM effectively becomes an Internet organ for the body, an alternate anatomical architecture—a publicly accessible, mobile acoustical organ for people in other places.

EPILOGUE

ALIVENESS, SURVEILLANCE, AND LIMINAL SPACES

- With sensor and computer technology, Art is exhibiting qualities of aliveness in its responsiveness, interactivity, and hybridity. Perhaps Art itself will become alive: Art as an Exo- and Endo-Organ of the body. An art that evolves, replicating, disseminating, and diversifying. Art gone viral. Grow an artwork on your body. The protuberance on your body is the artwork. Genetically Modified Art. The artist becomes a GENETIC SCULPTOR.

- Art will not be merely an outside-in experience, but rather an inside-out experience. Internal surveillance systems proliferate. Endo-architectures are engineered. The body becomes the host for its artifacts and instruments. Internal medical surveillance of the body needs to be implemented, and nano-sensors and nano-bots need to be deployed, to monitor and manage pathological changes in temperature and chemistry. Interfaces become more intimate. With wireless contact lens displays it will be possible to augment your vision with information and animations that both instruct and generate more potent affect with your environment. EPIDERMAL ELECTRONICS (stick-on, thin, flexible circuitry) can monitor and transmit body data. Electronic tattoos could also be stuck in strategic internal spaces.

- Bacteria now propel nano-machines, while rat neurons control the movements of robots. LIMINAL SPACES are proliferating with the blurring of the synthetic and of the genetic; of the cellular and of the machinic; of the living and the dead. Bodies that once existed now are plastinated and need not decompose. Near dead bodies need not die, sustained on their life-support systems. And the cryogenically preserved await reanimation at some imagined future. We engineer chimeras in the lab, transgenic entities of human, animal, and plant genes. Stem cells replicated in vitro are reinjected and repair tissue in vivo. Stem cells can become skin and muscle cells. A skin cell from an impotent male can be reengineered into a sperm cell. More interestingly, a skin cell from a female can be transformed into a sperm cell. Wombs from a deceased donor that would last the full term of a pregnancy will soon be able to be implanted into a patient. And further, if a fetus can be sustained in an artificial and external womb, then a body’s life would not begin with birth—nor necessarily end in death, given the replacement of the malfunctioning parts of the body. Birth and death, the evolutionary means for shuffling genetic material to create diversity in our species and for population control, will no longer be the bounding of our existence. The cadaver, the comatose, the cryogenically preserved, and the chimera occupy the same space at the same time. They are present to each other—and present for us.

- Having evolved with soft internal organs to better function biologically, we can now engineer additional external organs to better interface and operate in the technological terrain and media landscape that we now inhabit. The ear becomes a mobile and accessible acoustical organ for people in other places, the body an INTERNET PORTAL. People will become portals for distributed sensory and motor experiences. I might be seeing with the eyes of someone from London, listening with the ears of someone else in New York, while simultaneously another person from Tokyo actuates my arm to perform a task in Melbourne. The body operates beyond the boundaries of its skin and beyond the local space it inhabits. It has the distributed awareness of FRACTAL FLESH.

- A SPLIT BODY would not only possess a split physiology but it would experience parts of itself as automated, absent, and alien. The problem would no longer be possessing a split personality, but rather a split physicality. In our Platonic, Cartesian, and Freudian pasts these might have been considered pathological, and in our Foucauldian present we focus on inscription and control of the body. But in the terrain of cyber complexity that we now inhabit, the inadequacy and the obsolescence of the ego-agent body cannot be more apparent. A transition from psycho-body to cyber system becomes necessary to function effectively and intuitively in remote spaces, speeded-up situations, and complex technological terrains. Can a body cope with experiences of extreme absence and alien action without becoming overcome by outmoded metaphysical fears and obsessions of individuality and free agency?

- What is needed is not a Second Life, but rather a THIRD LIFE. An inverse motion capture system that enables an intelligent avatar to access a physical body and perform with it in the real world. A surrogate body that is actuated to move and animated to generate emotional expression. AVATAR AFFECT. To be both a possessed and performing body. To be avatar actuated. Clothe your body with a Virtual Skin. This would not be a cosmetic skin—it would change not only your appearance but also your operational capabilities.

- The realm of the Posthuman may no longer reside in bodies and machines, but rather in artificially intelligent entities sustained in electronic media and the Internet. Bodies and machines perform ponderously in gravity, with weight and friction. Images are ephemeral and perform at the speed of light. AVATARS HAVE NO ORGANS. Have no organs.

- The future is not what it seems nor what can be adequately imagined. The outcome of the present will neither be utopian nor dystopian. What’s next is not a meaningful question to ask. The future never is. To predict the future is to do an injustice to the present. The future is not fixed, hence not determined in the human sense. Possibilities collapse into actualities only in the present. It never is until it becomes the present; then it isn’t anymore. Complexity generates instability. The posture to take living in the present is one of INDIFFERENCE—as opposed to expectation. To be open to possibilities, to incorporate the accident, to generate ambivalence and uncertainty. Be indifferent and be on edge. The excitement of the unexpected.

- Feedback loops of self-improving intelligence generated by the exponential trajectory of improvements in computer technology will undoubtedly surpass human capabilities. It is seductive but simplistic to imagine this triggers the demise of the human body. Transhuman intelligence has always been a counterpoint to our own capabilities. But it is not about humans and/or machines but rather constructing intelligent systems of meat, metal, and code. Intelligence becomes embodied in diverse ways. Chimeric architectures proliferate. There will be no Singularity, only a multiplicity of CONTESTABLE FUTURES that can be examined and evaluated, possibly appropriated or most probably discarded.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

STOMACH SCULPTURE: Jason Patterson, Rainer Linz

EXOSKELETON: F18, Hamburg

PROSTHETIC HEAD: Karen Marcelo, Sam Trychin, Barrett Fox

The THINKING HEAD project is led by Professor Denis Burnham, who is the director of the MARCS Auditory Laboratories at the University of Western Sydney, Bankstown Campus. The ARTICULATED HEAD and the SWARMING HEADS were developed at the MARCS Robotics Lab by Damith Herath, Zhengzhi Zhang, and Christian Kroos, with the artist.

PARTIAL HEAD: TC&A, Mark Walters, Cynthia Wong, Vincent Wan, and Tim Wetherell

BLENDER: Adam Fiannaca, Rainer Linz

EAR ON ARM: Jeremy Taylor, Malcom Lesavoy, MD, Sean Bidic, MD, J. William Futrell, MD.