The appendix added here to the American edition is not intended to provide a detailed assessment of the current state of affairs. What I should prefer to do is to explain in what respects and how, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the history of Alexander appears strangely unchanged, and why, at the same time, it is in a process of transformation. On the occasion of his Inaugural Lecture at University College London in 1952, Arnaldo Momigliano observed, “. . . all students of Ancient History know in their heart that Greek history is passing through a crisis.”1 Almost sixty years later, I am tempted to think that the history of Alexander is passing through a similar phase, namely a “crisis,” which can and should be seen positively, provided it is analysed in this way by researchers, teachers, and scholars.

Even now, the person of Alexander and his history attract attention well beyond the circle of professional ancient historians. Frequently in books on European expansion and colonization, Alexander is seen as a predecessor, and his conquests sometimes serve as an introductory chapter.2 Another example arises from the wars conducted by the Americans in Iraq and Afghanistan, which have provoked reflections on “continuities between Alexander and Bush,” that are based on an epistemological model whose relevance should categorically be challenged.3 Some have interested themselves in the history of Alexander as “a fascinating journey into the history of leadership,” illustrative of the popular saying: “There is nothing impossible for those who persevere.”4 In a completely different arena, a team of biologists has tried to demonstrate recently that analyses of blood types support the thesis of Macedonian settlement in a valley in the Hindu Kush—a kind of revival of “The Man Who Would Be King”!5

A spate of specialist books and studies shows clearly how the publicity and release of Oliver Stone’s film Alexander (2004/2005) stimulated the imagination of publishers and authors. However, the production of these works is in step with the rhythm of a long-established historiographical tradition. It is clearly out of the question to attempt to list them here. The list would be interminable and of little practical value. I will content myself with drawing up two tables, one of bibliographical assessments dating to the years 1939 to 1993 (table 1),6 and the other of collections of articles published between 1965 and 2010 (table 2). Neither table pretends to completeness.

Various critical assessments have appeared in different languages from time to time. The first, edited by H. Bengtson and published in 1939 (A1), analyzed a selection of studies and articles that had appeared since 1933; the last, edited by J. Carlsen (A16), covers the 1970s and 1980s. Those who want, understandably, to go back before 1933, should note that the centenary of the publication of Droysen’s work (1833) brought the publication of several monographs (in 1931, Wilcken in German and Radet in French; in 1933, Andreotti in Italian and Tarn in English).

It is also worth consulting the methodological introduction (in Italian) to the monograph by R. Andreotti,7 which has had a lasting influence (cf. A2, 4, 7), and (in French) the very detailed reviews of P. Roussel and G. Radet of studies published in their time (between 1931 and 1934).8 Other articles allow for a specific focus, sometimes in a political context.9 Note also the reissues with commentary of the books by the “great ancestors” (Wilcken,10 Droysen11).

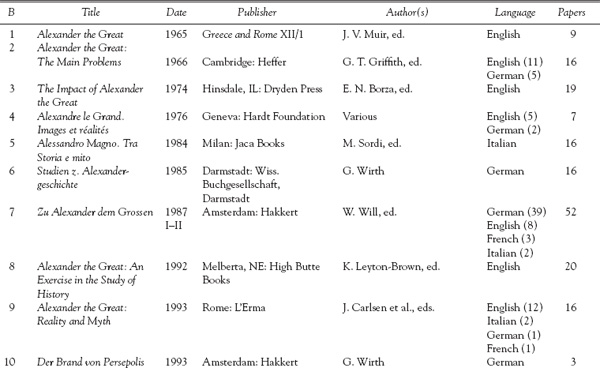

Since 1990, no one has really taken up the torch. The reason for this might appear to be the sheer magnitude of the task and the discouraging effect of the many difficulties that beset it. Sadly, this is not the case, as the production of works on Alexander has grown to such proportions that it has become an unstoppable flood, with each annual inundation threatening to swamp the sediment deposited by the preceding year’s tide! Apart from the innumerable biographies, which, when compared with one another, are all of doubtful originality, many books and manuals devoted to the Hellenistic period include an introductory chapter on the Macedonian conquest.12 The publications of collected articles (B1–3, 8, 12, 15, 17, 20),13 and proceedings of specialized colloquia (B4–5, 9, 13–14, 16, 18–19, 23) are beyond number.14 If we add the volumes of collected essays and articles (B6, 7, 11, 22), we end up with an impressive list of works (table 2) to add to the first one.

The tables call for a few brief comments:

(i) Linked to Europe’s cultural history is the decline, amounting to a virtual disappearance, of published scholarship in languages other than English. This is particularly the case for collective works and conference proceedings (B8–23 dating from 1999 to 2009, with the partial exception of B13 [1998]). English-speaking students run the risk of thinking (wrongly) that European studies of the subject have ceased entirely. When in 2004 W. Heckel posed the question, “What’s new in Alexander studies?” he might as well have asked “What’s new in English in Alexander studies?” as, with a single exception, no “foreign” study was mentioned in the entire article.15

TABLE 1

Critical Bibliographies (1939–93)

TABLE 2

Collected Essays and Anthologies on Alexander (1965–2009)

(ii) Also worth noting is the rate at which publications appear: three volumes of collected essays between 2003 and 2010, and no fewer than seven colloquia on Alexander the Great between 1998 and 2009, making a total of ten books in ten years. And that is without counting the hundreds of books and articles published in the same period.16 This exponential growth should not lead one to think that all these recent works are truly new. The manuals are certainly useful for teaching, but—with a few exceptions—structure and themes are virtually identical from one book to the next, certain articles are reprinted again and again, and major aspects of historical research are totally absent or not given the attention due them. This is particularly the case with the economic aspects of the conquest, apart from the reprinting of passages by Wilcken from 1931 (B3, B8). Just one very short article deals with Alexander’s monetary policy (B9),17 even though this is the one area where there is new evidence and interpretations have seen a striking transformation.

This state of affairs may explain the tone of a recent review:18 “In Alexanderland, scholarship remains largely untouched by the influences which have transformed history and classics since 1945.” The chosen target (Fact and Fiction, B13) is not perhaps the best for such a dismissive judgment, and it requires some qualification, but in general terms several of the reviewer’s remarks have hit home. There are very real gaps in current Alexander histories.19 G. T. Griffith had already drawn attention to one of the lacunae in 1966 (B2, ix), when he deplored the absence of any full study of Alexander’s ability (or not) to transform the situation he found in the empire. Sadly, forty years on, this question has still not received the attention it deserves—either in most of the manuals or in the specialist colloquia, which I have just discussed.20

(iii) Research into the historiography of Alexander is strikingly limited. Despite the studies by Bikerman and Momigliano, it continues to be asserted as a self-evident truth that the study of Alexander only begins with Droysen’s Alexander of 1833.21 This is simply not the case. If we are to refresh our historiographical methods and aims, it will be essential to trace the elaboration and evolution of the dominant image of Alexander the Great from the eighteenth to the twentieth century.22 Such a study must be conducted in conjunction with an analysis of the contemporary European images of Persia and the “Orient.”23 Historiography is not a substitute for history, but it helps the process of reflection on issues and their assessment. It makes it possible to see more clearly the circumstances in which this or that thesis emerged and why it may reappear without any apparent reason. For example, a “novel” thesis has recently been resurrected, condemning Alexander for marching against Egypt after Issus rather than pursuing Darius. The king, according to this, was moved to do so by his overwhelming desire (pothos) to consult the oracle of Amun. We are asked to see here an example of Alexander’s strategic mistakes and proof of his “irrationality.”24 In fact, this discussion began at the end of the seventeenth century, and spread in the context of the “canonical history” of the eighteenth century (e.g., Rollin and Mably in France; Prideaux and Shuckford in England). Its objective was to condemn Alexander’s “extraordinary rashness” and his rejection of Darius’ diplomatic overtures.25 (Voltaire had already settled the matter brilliantly!) Plainly, this type of moralizing history has come back with vigor in the last fifteen years.

(iv) Of course, any progress is limited by the scant nature of the sources, apart from the Graeco-Roman literary ones, that document the history of Alexander directly. The most recently found and published piece of evidence is a “medallion,” which is said to have come from the treasure of Mir Zakah in Afghanistan (Fig. 10a-b).26 It is of gold alloy and of a weight similar to a double daric (16.75 grams). The reverse of this unique medallion shows an elephant walking to the right, with the letters BA (standing for Basileos Alexandrou, according to Bopearachchi, although he also expresses some well-founded doubts). On the obverse is “the head of Alexander, covered with an elephant’s scalp; he wears an aegis, or the shield of Zeus, and the ‘ram’s horns’ of Ammon.” Some features are comparable to the coin series known as the “elephant coinage,” the dating and significance of which remain highly contentious (Fig. 3).27 The “medallion” is thought to have been struck in India in Alexander’s lifetime, after his victory over Poros. It would then be the only contemporary portrait of Alexander, and would have served as a prototype for the coins struck by Ptolemy using his image (Fig. 10C). It would also bear testimony to Alexander’s divinization in his lifetime.

Unfortunately, some specialists express serious doubts about the medallion’s authenticity,28 while others are critical of the first editor’s presentation and argumentation.29 The dossier as a whole is a kind of paradigm of the uncertainties and assumptions that beset current studies of Alexander.

Fig. 10A–B. The gold “Alexander Medallion” from the Mir Zakah (Afghanistan) Hoard, discovered in 1992. A (obverse): Head of Alexander wearing an elephant’s scalp. B (reverse): elephant. Photo: copyright Osmund Bopearachchi.

Fig. 10C: Alexander with an elephant’s scalp on his head, on a coin struck by the satrap Ptolemy after 323 BC. From P. Francke and M. Hirmer, La monnaie grecque, Paris (1966): Pl. 217, no. 29.

Having expressed these criticisms, it seems to me more constructive to emphasize recent advances, which means repeating an earlier observation about the evidence.30 This is simply the fact that, as Alexander is situated at the confluence of Macedonian and Achaemenid history, the study of his career has fed both of those disciplines and it must in turn be fed by them. The unprecedented development over the last thirty years of research both on the Argead kingdom and on the empire of the Great Kings has brought, and continues to bring, a regular harvest of unpublished documents that raise new questions, which provoke new ways of approaching the history of Alexander.

We can gain an impression of how things stand by looking at what was, at the time (1948), the first real historical synthesis of the Persian empire, namely A. T. Olmstead’s History of the Persian Empire. The book was published posthumously thanks to his colleagues at the Oriental Institute of Chicago and the devotion of his daughter.31 It ends with an almost lyrical report on the recent strides made in the empire’s history:

For the whole empire period, archaeologist and philologist have come to the aid of the historian. . . . No longer are we entirely dependent on Greek “classics” for the story of Persia’s relations with the West. . . . Close to twenty-three centuries have elapsed since Alexander burned Persepolis; now, at last, through the united effort of archaeologist, philologist, and historian, Achaemenid Persia has risen from the dead. (524)

In order to underscore his point, Olmstead contrasted the profusion of evidence relating to the Persian empire with what he considered the lamentable state of evidence for Macedon:

The Macedonia of Alexander has disappeared, almost without trace. Its older capital Aegae is a malaria-ridden site and nothing more. . . . The tombs of the Macedonian rulers, where Alexander had thought to be gathered to his fathers, have never been found; his own capital, Pella, is a mass of shapeless ruins. . . . But Persepolis stands to this day. (522–23)

Since Olmstead wrote these lines, Macedonian history has developed enormously, thanks to the joint efforts of archaeologists and epigraphists. We could in fact borrow his words on Persian history and apply them to Macedon: “No longer are we entirely dependent on Greek ‘classics’ for the story of Macedonian relations with the South!” Or we might go one better and quote Miltiades Hatzopoulos, one of the protagonists of this profound historiographical shift, in a recent work:

Half a century after the start of systematic, large scale excavations, the huge labour by archaeologists, who have dragged from the earth ruins hidden in the past, and the patient work of all the scholars who have concentrated the expertise on their finds, have revealed an inhabited land that had been terra incognita and given a face to the people, enigmatic until that point, whom Alexander led to the ends of the earth.32

Hatzopoulos’ statement seems to echo, sixty years later, that of Olmstead. Taken together, they tell us quite simply that the Macedon of Philip and the empire of Artaxerxes III/IV are now open to the gaze of historians working on Alexander and Darius.

Historians of Alexander will not be surprised by the first part of that observation. “The Macedonian Background” is an obligatory chapter in their publications, and some are remarkable connoisseurs of Macedon.33 I do not intend to give here a description of the most recent Macedonian discoveries. I shall limit my comments to two finds, one archaeological, the other epigraphic. It is well known that when discussing the necropolis at Aegae (the bibliography on which is immense, bordering on the uncontrollable), discussions of the dating of Tomb II (Philip II or III?) automatically involve discussion of the cross-cultural influences between Macedon and the Achaemenid world. Does the motif of the lion hunt belong to Macedonian tradition or does it indicate a borrowing from the Achaemenid world transferred to Macedon in an almost instant response to Alexander’s conquest?34

The many new inscriptions relate largely to the Hellenistic period. Their publication history can be followed in the section “Macédoine” (under the name Hatzopoulos) of the Bulletin Épigraphique of the Revue des Études Grecques, beginning in 1987.35 Alexander’s reign is illuminated by a number of inscriptions.36 These provide evidence of a herocult in honor of Hephaestion,37 and a dossier on relations between Alexander and the Greek sanctuaries,38 but we must give prominence here to an inscription from the city of Philippi. It was discovered in 1936, but first published by Vatin only in 1984; since then it has been reedited several times.39 There are problems with the restoration of the text and with its historical interpretation, as a result of which considerable controversy has arisen, in particular between Hammond and Badian.40 Several interlinked lines of enquiry are raised by this document: a) that concerning the precise territory of the new city founded by Philip in eastern Macedon, and thus the geography and topography of the region; b) that concerning intervention by the royal administration (well attested in other kingdoms) as the arbiter on frontiers and thus of relations between kings and cities at the time of Philip and Alexander;41 c) questions of Macedonian administration in Alexander’s absence, and the relations between the royal camp while on the move and his kingdom in Europe (including communications between them); d) and finally, the question of Alexander’s territorial objectives at the time of his departure from Macedon.

This last is precisely the larger perspective that Hatzopoulos wished to emphasize in a 1997 article.42 On the basis of his readings and the connections he makes with the historical context, he insists that we have here proof that Alexander changed his plans abruptly at Persepolis. Instead of turning back to Macedon (as, according to the author, he had intended), he decided to continue the war against Darius.

We can obviously either accept or reject that hypothesis—and this is not the place to go into a detailed analysis.43 But, given the major impact such a historical revision has on the much discussed problem of the burning of Persepolis (see above, chapter V), it is very odd that the inscription is only cited in that context in three of the articles included in the colloquia on Alexander (B13: 82–86),44 of which two simply refer to it in passing (B14, B15);45 odd too that the dossier has never been the subject of a full examination in any of the numerous collective volumes published between 1965 and 2009 (table 2). As far as I am aware, neither does it figure in any of the more recent monographs and articles dealing with the Persepolis affair, and it is absent as well from a recent colloquium on the teaching of Alexander’s history in American universities (B19 [2007]). And yet this is a document that raises important educational and epistemological issues relevant to the question of “documentary proof,” which is so important in our profession, and to the interaction of literary and epigraphic sources. It is of infinitely greater value to the historian than, for example, yet another account of that elusive phantom figure Cleitarchus.

When we turn to the place occupied by the Persian empire in the current historiography of Alexander, the situation is somewhat different. There is often no analysis of the Achaemenid adversary at all, and certainly none of any depth. The history of the conquest is organized exclusively around the figure of Alexander and his itinerary. Whereas the nineteenth-century works (from Droysen in 1833 onwards), as well as the eighteenth-century manuals, always included an introductory chapter on the Achaemenid state, this has disappeared, and/or the Achaemenid sources are ignored. It is as if, for example, a French historian of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 had failed to take account of the situation in Prussia and the German lands and centered his whole narrative on Napoleon III while forgetting Bismarck! Paradoxically, there has been more interest recently in the figure of Darius46 (a biographical approach to whom is literally impossible in the absence of documentation),47 but in the process the Persian empire he reigned over, about which we have more and more information, has been forgotten.

Further, more often than not these articles tend towards a kind of “rehabilitation” of the last Great King, by simplistically reversing the perspective. The task of the historian, however, is not to create a history of “victims,” any more than to write a history of “conquerors.”48 Rather, we must try to reconstruct a global history, in other words one that is complex, enfolding multiple perspectives. While the ancient sources have glorified Alexander and his conquests, the historian should not feel obliged to go to the other extreme and display, naïvely, a “compassionate admiration” of the Persian empire, comparable to the attitude supposedly evinced by Alexander when he found Darius’ corpse!49 Does it need repeating that a reconsideration of Achaemenid history is not the same thing as either the “rehabilitation” of Darius or an exaltation of the grandeur of his empire? The objective is a reevaluation (the scientific approach), not the rehabilitation (the moralizing approach) of Achaemenid history. Our aim is to understand better what state the empire was in when it was attacked and invaded by the Macedonian army.

At the same time, the accelerating development of Achaemenid history has obviously not been completely ignored. One recent writer, who presents herself as a nonspecialist on Alexander but is anxious to take an original approach, has chosen to set Alexander and the conquest into the Macedonian context vis-à-vis Achaemenid history.50 Reflecting on how we should teach the history of Alexander today, Flower expressed the same idea:51

Alexander’s achievement and its consequences must be understood against the background not just of earlier Greek and Macedonian history, but also of Persian history.

One reviewer emphasized that book’s appeal as follows:

As such, the approach is welcome, for much of the excellent scholarship on the development of the Macedonian kingdom to the death of Philip II . . . and on the nature of the Achaemenid empire on the eve of the Macedonian invasion . . . tends to be beyond the reach of many students.52

However, what needs to be stressed is the marked and highly revealing imbalance between the information on Macedon and that on the Achaemenid empire, that was brought into play by the author of the book: her pages on Achaemenid history (159–73) are extremely general and not really linked to the history of the Macedonian conquest.53

It would seem, then, that the recent advances in Achaemenid historiography are not always correctly evaluated and taken fully into account.54 Flower, in an otherwise interesting presentation (B19 [2007]: 422, n. 20), rather oddly described the British Museum exhibition of 2005 as a “major revisionist exhibition,” because, in his opinion, its aim was “to rehabilitate Persian culture.” But this was hardly the first time that an exhibition devoted to the cultural patrimony of Achaemenid Iran (which stood in little need of “rehabilitation”) had been organized, and we did not have to wait until 2005 to know that the Persians had “a sophisticated and interesting culture of their own.” With its negative connotations, the adjective “revisionist” is exceptionally problematic and misleading. There is also the danger that nonspecialists and students might confuse this with the other “revisionist school” (or rather one identified as such!) in the historiography of Alexander. In that context, the adjective generally describes those writers who have been influenced by the debunking of Tarn’s 1933 theses (B1 [1966]: 243–86) by Badian in 1958 (B1 [1966] : 287–306, B22 [2010]); however, not all authors who distance themselves from Tarn’s approach would consider themselves “revisionists”!55

This is perhaps the appropriate place to suggest what we can expect from the contribution of Achaemenid history, and at the same time to stress its limitations, so as to avoid any misunderstandings.56 One important point to note: it will never be possible to write a narrative history of Alexander from the perspective of the conquered, as we have neither continuous accounts nor even partial ones from Persia, Babylonia, or Egypt.

(i) As we have seen, Babylonian texts are the most useful. A well-known Babylonian tablet gives us a detailed image of the weeks from the Battle of Arbela to Alexander’s entry into Babylon and of the conditions surrounding his acceptance by the Babylonian elites.57 This document can, in turn, be compared to the Graeco-Roman texts, whose narrative style adds complementary and/or contradictory elements.58 However, the meaning of cuneiform texts is not always clear. For example, the combined mention of Darius, Alexander, and Bessos in a Babylonian chronicle of this period remains hard to understand, and it cannot provide unambiguous evidence.59

Other sets of tablets, of a rather more pedestrian nature, give information on variations in the levels of the Euphrates and on regular work carried out on the Pallukatu (Pallacopas) canal. In its way, such information can be very helpful to historians trying to understand the nature of Alexander’s work in 324/3 on Babylonia’s rivers and canals.60

(ii) A single coin of Mazday/Mazaeus has given rise to a hypothesis on the maintenance of Persian positions in Syria after the Battle of Issus. But even if the coin is indeed authentic, it should not really be used in that way.61

(iii) The Aramaic papyri, seal impressions (Fig. 11), and coins found in the Wadi Daliyeh (about 30 km from Jericho), which have been known for half a century, are thought to relate to the anti-Macedonian revolt of 331 known from Quintus Curtius.62 The assumption is that well-to-do Samarians, on the occasion of the revolt, fled the city and took refuge in the caves together with their families and private archives. But Quintus Curtius’ passage can also be linked with passages in late authors, as well as to an inscription and coin from the Roman period. Putting all these together, they would attest to a joint action by Alexander and Perdiccas in Samaria and Gerasa.63 This body of material is particularly interesting in that it allows us to gauge the extent of our ignorance. By following the progress of the Macedonian army step by step and focusing on Alexander’s personality and conduct, the literary sources tend to leave in the shade the “secondary” campaigns, which were undertaken alongside the offensives by the bulk of the army.64

(iv) The Lydian inscriptions dating to one year of Alexander’s reign provide no direct information, and it is difficult (as is the case with some Babylonian documents) to determine with any certainty which king of the name Alexander is meant.65

Fig. 11. The “Persian Hero” grappling with flanking animals, from a Samarian seal impression. Drawing and description in M.J.W. Leith, Wadi Daliyeh I: The Wadi Daliyeh Seal Impressions (Discoveries in the Judaean Desert XXIV), Oxford 1997, no. WD 17, 209–210.

(v) The same problem—i.e., which Alexander is meant by the designation the “reigning king”—divides specialists dealing with some of the Aramaic administrative documents from Idumaea. Is it Alexander the Great or his son?66 If it is Alexander the Great, then the ostracon AL 38*, dated to 16 Siwan, year 2 of Alexander the king, would be of June 26, 331, when Alexander was returning from Egypt and moving towards the Euphrates. The problem with this is that it supposes the existence of an Alexander era specific to the regions of Palestine. As a result the assumption in most recent studies is that the Alexander of the Idumaean ostraca is Alexander IV.67

(vi) The new Aramaic documents from Bactria are extremely important, particularly in relation to the issue of the transition from the Achaemenid to the Macedonian period. Nevertheless, they still pose some problems as to exactly how they link up with the history of Darius, Alexander, and Bessos. Three types of documents demand consideration in this connection:

(a) Most important is the fact that we have here a set of documents dated to one year of Darius III, namely 18 wooden sticks recording debts, all from year 3 of Darius (D1–18).68

(b) A document (C1) is dated “In the month of Kislev, year 1 of Arta[xerxes] the King.” It records the delivery of various products to a certain Bayasa, “when he passed from Bactra to Varnu.” The editors propose to identify him with Bessos, in the course of his flight from Bactra, and suggest that Bessos is also the reigning king Artaxerxes. The date would then be November–December 330. This is very exciting evidence, as it would give us a direct insight into the period when Bessos was fleeing before Alexander. But it seems rather odd that in one and the same document, the same individual is called both by his own and his regnal name.69

(c) Another document (C3) is certainly dated to Alexander’s reign, as follows: “On the 15th of Siwan, year 7 of Alexander the King” (col.1, ll.1–2), which is June 8, 324 according to the editors. Again it is an administrative text recording the transfer of a variety of products (wheat, barley, millet, etc.) as rations over a period of three months (Siwan, Tammuz, and Ab), from storehouses at Airavant and Varaina. Unfortunately neither location is known.70

The proposed dating introduces information that is new. In Babylonia, the contemporary cuneiform documents are dated exclusively in terms of Alexander’s regnal years in Macedon, for which reason there are no tablets dating from years 1 to 6 of Alexander, as these correspond to years 1 to 6 of Darius. The change from Achaemenid to Macedonian control is marked by the accession year (known as year 0) of Alexander, which lasts just to the next Babylonian year, i.e., April 3, 330. At this point, Alexander’s year 7 begins and continues to Nisan, that is March of 329.71 Even though no official document records them, all events from the pursuit of Darius to Alexander’s arrival in Bactria at the end of winter/beginning of spring 329 fall into this very year 7. It is also in year 7 that, theoretically, the proclamation of Bessos as King Artaxerxes falls. If we follow this dating method, then the date of the Bactrian document would be June 15, 330. The editors consider that impossible, as Alexander had not yet arrived in Bactria; they have, therefore, chosen to date it to June 8, 324. This seems logical, but it is surprising that the Bactrian chancellery should choose to begin Alexander’s reign according to a Babylonian computation, which recent studies show was never used in Babylonia itself.72

In conclusion, I should like to turn to another instance, which illustrates the importance of the Achaemenid context for reconstructing Alexander’s campaigns. In 1978, D. W. Engels published a study of Alexander’s logistics, which was rightly welcomed as presenting a new and virtually unexamined aspect of Alexander’s history.73 He observed that the success of a long-term military expedition was inconceivable without the logistical planning necessary to ensure the resupply of resources all along the route of its advance. Alexander’s success thus depended as much on the logistical measures he took in the course of his campaigns as on the stocks of provisions he might find and mobilize in the lands he was traversing and conquering.

This meant that Achaemenid resources were absolutely indispensable to Alexander—and not merely agricultural products but also the institutions established by the imperial administration to create reserves and ensure their maintenance. A passage in the pseudo-Aristotelian Oikonomika (II.2.38) illustrates brilliantly how Alexander’s administration co-opted Achaemenid measures for maintaining reserves in the magazines along the royal roads. When Alexander made use of the Achaemenid road system, he knew well how “to turn to his own advantage the logistics the Persian authority had established to ensure its survival.”74

In this respect, Engels’ use of the Graeco-Roman sources leaves something to be desired. On p. 72, for example, he declares that Persis was “sparse and rugged,” for which his sole witness is Herodotus 9.22 in a passage created to make the point that people who are poor are perforce ready to become conquerors! Other evidence, some of it from eyewitnesses, provides far more precise and credible information.75 What is more, R. T. Hallock’s edition of the Persepolis Fortification Tablets (1969–1978) was already published and readily accessible at this point. Both agricultural production and the raising of flocks in Persis were extensive, and, in 330, there were certainly a substantial number of garrisoned storehouses, which Alexander could use to feed his army.76 It is also a structural weakness of Engels’s book that he rarely discusses the grain and other food reserves held in the satrapies, a system well attested by many Achaemenid documents, as well as by the classical sources.77 As a result of these omissions, Engels overstresses the explanatory (and often exclusive) value of the (of course, important) diverse modes of transport, and the (no less important) dates of harvests.

Yet one further example: not a single account of the Macedonian expedition in Bactria-Sogdiana refers to the existence of the region’s highly developed irrigation system, known from excavations (of which Engels is aware, pp. 98–100). The presence of irrigation agriculture must have dictated the choice of sites for colonization and urbanization made by Alexander and his successors.78 In addition to the archaeological evidence,79 the more recent Aramaic documents from Bactria (discussed above) provide extremely important information. Dating from the end of the Achaemenid era and Alexander’s reign, several of these Aramaic texts attest the existence of official storehouses, filled with foodstuffs of all kinds, on which the administration could draw to feed men and animals (fodder).80 It also had at its disposal numerous pack animals (donkeys and camels). This new material helps, however indirectly, to throw light on Alexander’s logistic and strategic choices.

Unsurprisingly, the information contained in the late Achaemenid sources does not turn the narrative of events upside down. At the same time these sources do throw light on the various lands of the empire, which are now becoming ever better known, and on the broad context in which Alexander conducted his military and organizational enterprises between 334 and 323. The observations and comments above lead us directly to the question, which has long been debated, of the continuities vs. changes from the Achaemenid to the Hellenistic period, including the ancillary question of the specific role played by Alexander, whether knowingly or not, in this process. In 1979, I tried to make an assessment and to suggest some directions for future research. I concluded that, in this respect, Alexander’s reign could be regarded as an integral part of the history of the Middle East as initiated by the conquests of Cyrus and Cambyses. I ended with the following sentence:

Was he the first of a long line of Hellenistic rulers? Of course! But I think that in the context of the history of the Near and Middle East in the first millennium, Alexander can also be considered as “the last of the Achaemenids.”81

It is of course possible to question the validity of the expression “last of the Achaemenids.”82 But the problem is not in essence one of terminology, because, once the phrase is removed, the question of Achaemenid heritage and Macedonian innovation remains.

In the overall historiographical tradition, neither the underlying question nor the response I formulated thirty years ago is in any sense innovative. In this area, the influence of Rostovtzeff has been decisive, as has that of Aymard, Bikerman and Préaux, to name only three.83 The problems are as old as the first thoughts on the Hellenistic period. When H. Bengtson in 1939 asked himself about the different views put forward by Tarn (B2: XII) and Berve (B2: VI) on the question of “universal brotherhood” (Weltverbrüderung), he could, with no need for justification, refer to “the question so often raised in recent years whether Alexander acted (or not) as a successor to the Achaemenids” (A1: 171). Nowadays, the continuity between Alexander and the Achaemenid model is often spoken of as if it were obvious, even though we, of course, question the nature and depth of that heritage. In 1992, Édouard Will reproached the author (H. Gehrke) of a book on the Hellenistic period for having neglected this aspect of the topic. His criticism is worth citing here:

I must express a reservation which, beyond Alexander, affects the whole book: the object of the conquest itself, by which I mean the Persian empire, appears here in a somewhat ghostly fashion. But can we understand Alexander’s empire and the subsequent Hellenistic empires of the Orient, without a reasonable understanding (however limited that may be) of the Achaemenid empire? . . . The slightness of the eastern substratum of the Hellenistic world leaves us craving more. . . . Recent studies have made us reevaluate our image of the Achaemenid empire, which offered in many respects the best global solution to the complex problems of the ethnic and cultural mosaic of the pre-Islamic East. . . . Alexander will certainly have understood that his work could not last unless he made use of the Achaemenid model. (Gnomon 64/1 [1992]: 68–69.)84

I do not intend to reexamine now a topic that is the central theme of this entire book. To end, I would simply underscore my critical message to the historian: that new readings of the available documents, the corpus of material found in recent years, and the clearer formulation of problems should between them encourage us to write a different history of Alexander; and this will be a history not limited to the period bounded by the two fixed dates 336/4 and 323. Rather it will be a history dynamically integrated into the longer period of transition that is defined at its upper end by the reigns of Philip II and Artaxerxes III (c. 350), and its lower end by the establishment of the new Hellenistic kingdoms around the year 300.

1 George Grote and the Study of Greek History, London, 1952: 4 (= A.D. Momigliano, Studies on Modern Scholarship, Berkeley, CA 1994: 16).

2 E.g. A. Pagden, People and Empires: Europeans and the Rest of the World from Antiquity to the Present, London 2001. In chapter 1, Pagden calls Alexander “the first world conqueror” (pp. 13–27), unfortunately forgetting that before him “the most extensive empire the ancient world had ever seen” was in fact the Achaemenid empire.

3 See F. L. Holt, Into the Land of Bones: Alexander the Great in Afghanistan, Berkeley, CA 2005. An excellent specialist on Alexander and Central Asia, Holt states that he is aware of the risk of “presentism,” which he nevertheless does not, in my view, avoid; see the apt criticisms of E. Borza (B19 [2007]: 439–40) of a comparable approach taken by J. Romm, “From Babylon to Baghdad: Teaching a Course after 9/11,” (B19 [2007]: 431–35).

4 M.F.R. Kets de Vries and E. Engellau, Are Leaders Born or Are They Made? The Case of Alexander the Great, London and New York 2004. The point of the book is indicated by the title of the last chapter: “Leadership Lessons from Alexander the Great.”

5 S. Firasat et al., “Y-chromosomal Evidence for a Limited Greek Contribution to the Pathan Population of Pakistan,” European Journal of Human Genetics 15 (2007): 121–26. (I owe this reference to my friends, Biaggio Virgilio and Omar Coloru, in Pisa.)

6 The reader will find here global analyses (A1–2, 5, 7–8, 11, 13, 16) and assessments of more specific topics (A3–4, 6, 12, 14–15); there are also two books of a very different sort (A8 and 11).

7 Il problema politico di Alessandro Magno, Rome 1933: 5–13.

8 E.g., Journal des Savants, February 1932: 49–60 (Roussel on Wilcken 1931 and Radet 1931); Revue Historique 173 (1934): 80–90 (Radet on Wilcken); Journal des Savants, July-August 1935 (Radet on Tarn 1933, Andreotti 1933, and Bickermann 1934).

9 E.g., J.-R. Knipfing, “German Historians and Macedonian Imperialism,” AHR 26 (1921): 657–71.

10 The English translation of 1932 was republished in 1967 (New York and London), with “An Introduction to Alexander Studies,” by E. N. Borza (pp. ix–xxviii).

11 The French translation (1883) of the Geschichte des Hellenismus (1877) was republished in 2003 (Ed. Laffont, Paris, 1 vol.) and in 2005 (Ed. J. Millon, Grenoble, 2 vols., with a long introduction by P. Payen, pp. 5–82); the French translation (1935) of Droysen 1833 is regularly reissued. For reasons that I do not understand (the instant and firm disagreement expressed by George Grote against Droysen’s thesis?), Droysen’s books have never been translated into English.

12 E.g., F. W. Walbank, The Hellenistic World, London (1981), chapter 1, “Alexander the Great.”

13 I have not taken into account collections that are not exclusively concerned with Alexander (e.g., Briant, Rois, tributs et paysans: 161–74; 281–330; 357–404), nor the issues of Ancient World devoted to him in the 1980s and 1990s, nor the series Ancient Macedonia (Thessaloniki 1974–).

14 Cf. http://people.clemson.edu/~elizab/Alexander%20conference.html.

15 http://www.apaclassics.org/outreach/amphora/2004/Amphora3.1.pdf.

16 In the book by M. Kets de Vries and E. Engellau (nonspecialists) published in 2004 (see above n. 4), the authors cite the round figure of “30,000 books and articles” published at the time of their writing (p. xxii, n. 1). I have no idea where they obtained this figure.

17 At this time, its author, the late Martin Price, had already planned to publish his great work on the subject (1991).

18 J. Davidson, “Bonkers about Boys,” London Review of Books (November 11, 2001: http://www.lrb.co.uk/v23/n21/davi02.html), together with A. B. Bosworth’s response (London Review of Books, January 3, 2002), and that of W. Heckel in the article cited above (n. 15).

19 See also the remarks by M. Flower in B19 (2007): 419–20.

20 On this, see my discussion in B20 (2009), chapter 9.

21 The bibliography on Droysen is too vast to cite, and is largely in languages other than English. Bravo’s book (Philologie, histoire, philosophie de l’histoire. Étude sur J.-G. Droysen historien de l’Antiquité, Wroclaw-Warsaw-Cracow 1968) remains the fundamental study. In English, see the convenient and recent discussion by A. B. Bosworth, “Alexander the Great and the Creation of the Hellenistic Age,” in G. Bugh, ed., The Cambridge Companion to the Hellenistic World, Cambridge 2006: 9–26; and “Johann Gustav Droysen, Alexander the Great and the creation of the Hellenistic Age,” in B 21 (2009): 1–27.

22 See my observations in The Oxford Handbook of Hellenic Studies, Oxford, 2009: 77–85, and the bibliography there. I have been working on this topic for several years, and am currently preparing a book on the subject.

23 Apart from Briant, Darius dans l’ombre, see also my “Alexander and the Persian Empire: Between ‘Decline’ and ‘Renovation’,” in B20 (2009): 171–88; “Le thème de la ‘décadence perse’ dans l’historiographie européenne du XVIIIe siècle: remarques préliminaires sur la genèse d’un mythe,” in L. Bodiou et al, eds., Mélanges Pierre Brulé, Rennes 2009: 19–38.

24 E. F. Bloedow, “Egypt in Alexander’s Scheme of Things,” Quaderni Urbinati di Cultura Classica 77/2 (2004): 75–99. The writer begins his investigation with Droysen, but the discussion of this theme has a much longer history. The same thesis is also found in a very naïve article by I. Worthington, “How Great Was Alexander?” AHB 13/2 (1999): 39–55, esp. 45–46 (= B17 [2003]: 308); note F. L. Holt’s justified criticism (B17: 322).

25 See my article, “Montesquieu, Mably et Alexandre le Grand: aux sources de l’histoire hellénistique,” Revue Montesquieu 8 (2005–2006): 151–85 (162–77).

26 O. Bopearachchi and P. Flandrin, Le portrait d’Alexandre le Grand, Monaco and Paris 2005. (The subtitle, Histoire d’une découverte pour l’humanité, is needlessly pompous.) An international colloquium on the object was organized by Bopearachchi at the École Normale Supérieure (Paris) on March 26, 2007. The proceedings are not yet published.

27 See the brief discussion of the issue in Le Rider, “A Mysterious Group of Silver Coins,” Alexander the Great: 247–52; and a detailed discussion in F. L. Holt, Alexander the Great and the Mystery of the Elephant Medallions, Berkeley, CA 2003.

28 E.g., K. Dahmen, The Legend of Alexander the Great on Greek and Roman Coins, London 2007: 9 (“of questionable authenticity”).

29 See the recent study of S. Bhandare, “Not Just a Pretty Face: Interpretations of Alexander’s Numismatic Imagery in the Hellenistic East,” in H. P. Ray and D. T. Potts, eds., Memory as History: The Legacy of Alexander in Asia, New Delhi 2007: 208–56, who inserts the medallion into the long-term debate about the “elephant coinage.”

30 This is an observation that I have made before, more than once; see most recently, The Oxford Handbook of Hellenic Studies, Oxford 2009: 82–84.

31 See the Foreword by George Cameron (p. v), who was publishing, in the same year, the first volume of the Persepolis tablets (Persepolis Treasury Tablets, Chicago, IL 1948).

32 M. Hatzopoulos, La Macédoine. Géographie historique, langue, culte et croyances, institutions, Paris 2006: 93; see also, M. Hatzopoulos, Macedonian Institutions under the Kings I (1996): 37–42, and his synthesis, “L’État macédonien antique: un nouveau visage,” CRAI 1997: 7–25.

33 I am thinking particularly of Eugene Borza. Apart from his general book on Macedon (In the Shadow of Olympus: The Emergence of Macedon, Princeton, NJ 1990), he has published two collections of his articles on Macedon (Association of Ancient Historians, 1995 and 1999), as well as editing a volume of essays by various authors on Alexander (B3) and providing an “Introduction to Alexander Studies,” as the preface to a reissue of the English translation of Wilcken (Alexander the Great, New York 1967: ix–xxviii); see also his contribution to a debate on teaching Alexander history (B12 [2007]: 436–40). On Borza’s work, see recently T. Howe and J. Reames, eds., Macedonian Legacies: Studies in Ancient Macedonian History and Culture in Honour of E. N. Borza, Claremont, CA 2008. See also the following footnote.

34 See most recently, O. Palagia and E. Borza, “The Chronology of the Macedonian Royal Tombs at Vergina,” Jahreshefte des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 122 (2007): 81–124 (90–103), with a full bibliography. On the Macedonian and Persian traditions of the hunt in the epoch of Alexander, see also my remarks in AchHist VIII (1994): 302–310, P. Vidal-Naquet’s contribution (now sadly forgotten), “Alexandre et les chasseurs noirs,” in Arrien entre deux mondes (Arrien, Histoire d’Alexandre, trans. P. Savinel, Paris 1984: 309–94): 355–65, and E. Carney, “Hunting and the Macedonian Elite: Sharing the Rivalry of the Chase,” in D. Ogden, ed., The Hellenistic World: New Perspectives, Classical Press of Wales and Duckworth 2002: 59–80.

35 The Bulletin Épigraphique 1987–2001 has been reprinted as four volumes (Paris 2007).

36 See R. M. Errington’s analytical study, “Neue epigraphische Belege für Makedonien zur Zeit Alexanders des Grossen,” in B13 (1998): 77–90.

37 Bulletin Épigraphique 1992, no. 309, and M. Mari in Studi Ellenistici XX (2008): 230–31 and n. 27 (dedication on a stela from Pydna, ca. 315–300 BC).

38 See now, M. Mari, Al di là di Olimpo. Macedoni e grandi santuari della Grecia dall’età arcaica al primo Ellenismo (Meletemata 34), Athens 2002: 203–262; see the epigraphical analysis on pp. 227–30 of relations between Olympias and Delphi during her son’s campaign, which complements E. Carney’s work, Olympias (2006): 49.

39 See M. Hatzopoulos, Macedonian Institutions II (1996), no. 6 (25–28); S. Ager, Interstate Arbitrations in the Greek World (337–90 B.C.), Berkeley, CA 1996, no. 5 (47–49).

40 The debates can be followed via the Bulletin Épigraphique 1987, no. 714; 1988, no. 495; 1990, no. 495; 1991, no. 417; 1993, no. 356; and 1994, no. 436.

41 This point is discussed by Farraguna in B15 (1998): 111–12.

42 “Alexandre en Perse. La revanche et l’empire,” ZPE 116 (1997): 41–52; the author had clearly stated his interpretation in the Bulletin Épigraphique 1987, no. 714; his view is repeated in no. 282. (1998): nn. 36 and 39.

43 I have never concealed my very serious reservations; cf. the 2002 and 2005 French editions of this book (p. 57, n. 1) and Briant, History (2002): 1047–48. It seems to me that the dating of the boundary marking (entrusted to Philotas and Leonnatos) to a time preceding 334 is much more persuasive than the very complex scenario presented by Hatzopoulos. See the similar criticisms of e.g., Errington (n. 36, above) and Ager (n. 39, above).

44 The detailed epigraphic and historical discussion by R. M. Errington, countering the readings and interpretations of Hatzopoulos (for his reply, see Bulletin Épigraphique 1998, no. 281).

45 M. Flower (B3 [2000]: 116, n. 85) observes briefly that the literary sources do not agree with Hatzopoulos’ interpretation, but does not treat the inscription itself; Brosius in B15 (2003): 185, n. 25, refers to it indirectly while analyzing the Persepolis affair.

46 Cf. J. Seibert, “Dareios III,” in B7, I (1987): 437–56; E. Badian, “Darius III,” HSClPh 100 (2000): 241–68 [= B22, 2010]; E. Garvin, “Darius III and the Homeland Defense,” in B16 [2003]: 87–112; see also C. Nylander, “Darius III—The Coward King. Point and Counterpoint,” in B9 (1993): 145–59.

47 See Briant, Darius dans l’ombre, esp. p. 530f. on Nylander’s idea in the wake of Widengren.

48 Pace J. D. Grainger, Alexander the Great Failure: The Collapse of the Macedonian Empire (2007): 189–90.

49 On this image, see Briant, Darius dans l’ombre, chapter 11: “Mort et transfiguration” (pp. 487ff.). It is this lachrymose tradition that G. Grote denounced as “almost tragic pathos” (cited ibid.: 103–104).

50 C. Thomas, Alexander the Great and His World, Oxford 2007: esp. p. x.

51 M. Flower in B19 (2007): 420.

52 E. Mackil, CR 58/1 (2008): 201. (Despite Flower’s identical observation [see the previous note], I am not convinced that this problem is exclusively one experienced by students.)

53 The same is true, for example, of P. Cartledge’s book despite its promising subtitle: Alexander the Great: The Hunt for a New Past, London 2004: 40–46.

54 See J. Lendering, BMCR 2008.09.62., and “Let’s Abandon Achaemenid Studies!” July 2008: http.livius.org/opinion/opinion0012.html; see also V. Vashakize’s excessively aggressive response (together with others), BMCRI 2009.02.02. I stress that such a polemical exchange gives a distorted, not to say caricatured, image of the state of Achaemenid history today.

55 E.g., Bosworth, Alexander and the East: p. v.

56 See on this the apt remarks of J.-P. Stronk, BMCR 2005.07.35.

57 Texts in R. Van der Spek, AchHist XIII (2003); 289–346; A. Kuhrt, The Persian Empire I (2007): 447–48.

58 To the familiar texts (Arrian, Quintus Curtius, etc.) P. Goukowsky’s recent article (“Le cortège des ‘rois de Babylone,’ ” Bulletin of the Asia Institute 12 (1998): 69–77) adds the evidence of Iamblichus; but its late date raises problems.

59 Cf. R. Van der Spek, AchHist XIII (2003): 303–308.

60 Briant, Studi Ellenistici XX (2008): 204–207 (with references to the Assyriological studies).

61 The problem is discussed by Lemaire, in Briant and Joannès, eds., La Transition: 407.

62 IV.6.9–10 (above, chapter I); see already Briant, History (2002): 713–16 and 1016 (with bibliography) and, since then, M.J.W. Leith, Wadi Daliyeh I: The Wadi Daliyeh Seal Impressions (Discoveries in the Judaean Desert XXIV), Oxford 1997, esp. pp. 3–35, and D. M. Gropp, Wadi Daliyeh II: The Samaria Papyri from the Wadi Daliyeh (Discoveries in the Judaean Desert XXVIII), Oxford 2001, esp. pp. 3–32. The latest papyrus (WDSP 1) dates to year 0 of Darius III and year 2 of his (unnamed) predecessor (March 19, 335), and was drawn up “in Samaria the citadel (birtha), which is in Samaria the province (medinah).”

63 See H. Seyrig, “Alexandre le Grand, fondateur de Gerasa,” (1965) in Antiquités Syriennes VIè série, Paris 1966: 141–44.

64 Apart from Quintus Curtius, IV.8.9–10 (Samaria), see IV.1.4 (Parmenion’s expedition in Syria) and IV.2.24, 3.1 (Alexander’s move from Tyre to deal with revolts in Lebanon): Atkinson, Commentary I (1980); 300–301, 369–70.

65 See T. Boiy, Kadmos 44 (2005); 165–74.

66 Different positions are taken by Lemaire in Briant and Joannès, eds., La Transition: 416–19, and Boiy, in La Transition: 48, 58–63; cf. Briant, “Empire of Darius” in B20 (2009): 152–55, with bibliography.

67 See in particular B. Porten and A. Yardeni, “The Chronology of the Idumaean Ostraka in the Decade or so after the Death of Alexander the Great and Its Relevance for Historical Events,” in M. Cogan and D. Kahn, eds., Treasures on Camel’s Humps: Historical and Literary Studies from the Ancient Near East Presented to Israel Eph’al, Jerusalem 2008: 237–50.

68 Documents dated to Darius III in the empire are collected in Briant, Darius dans l’ombre: 62–64 and 562–63 (together with a preliminary discussion of the Bactrian documents, p. 63 and n. 19).

69 For a presentation, translation, and detailed commentary on this document, see S. Shaked, “De Khulmi à Nikhšapaya: les données des nouveaux documents araméens de Bactres sur la toponymie de la région (IVe siècle av. notre ère),” CRAI November–December 2003: 1517–35. See my doubts on this dating in B20 (2009): 147, n. 28.

70 Shaked, Satrape de Bactriane (2003): 17–18.

71 See Briant and Joannès, eds., La Transition: 42–49 (Boiy) and 104–108 (Joannès).

72 Given that Alexander on leaving Parthia and Areia decided to pursue Bessos to Bactria from the moment of the latter’s proclamation as king, before being compelled to take the road back to Areia (Arrian III.23–25.1–6), we might be tempted to think that he was recognized as king from his year 7 onwards in accordance with the Macedonian pattern; but the suggestion is not free of problems.

73 Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army, Berkeley, CA 1978; on working out the rations needed for animals, see the critical comments by M. Gabrielli, Le cheval dans l’empire achéménide, Istanbul 2006.

74 Briant, History (2002): 317–74 (373); on the ps.-Aristotle passage, see Briant, “Empire of Darius,” in B20 (2009): 166–67.

75 Diodorus XVII.67.3, XIX.21.2–3; Quintus Curtius V.4.6–9.

76 See already my observations in Briant, Rois, tributs et paysans: 202–10, 329, 331–45; History: 733–37.

77 Cf. Xenophon, Anab. III.4.17, 31 (strategic materials).

78 Cf. Briant, Rois, tributs et paysans: 230–33; 247–48, 314–16; Briant, “Colonizazzione ellenistica e popolazione locale,” in S. Settis, ed., I Greci II/2, Florence 1999: 309–33.

79 See most recently, H.-P. Francfort and O. Lecomte, “Irrigation et société en Asie Centrale des origines à l’époque achéménide,” Annales HSS 57/3 (2002): 625–63.

80 On the fodder reserves in the empire, see the texts cited in Briant, “Empire of Darius,” in B20 (2009): 155, n. 65.

81 “Des Achéménides aux rois hellénistiques. Continuités et ruptures. (Bilan et propositions),” = Briant, Rois, tributs et paysans: 291–30 (p. 330).

82 R. Lane Fox, “Alexander the Great: ‘Last of the Achaemenids’?” in C. Tuplin, ed., Persian Responses: Political and Cultural Interaction with(in) the Achaemenid Empire, Swansea 2007: 267–311; H.-U. Wiemer, “Alexander—der letzte Achämenide? Eroberungspolitik, lokale Eliten und altorientalische Traditionen im Jahr 323,” Historische Zeitschrift 284 (2007): 281–309. Both articles deserve a thorough analysis; see some preliminary remarks in Briant, Studi Ellenistici XX (2008): 203, nn. 154, 162, 166; Briant, “The Empire of Darius,” in B20 (2009), nn. 112, 122, 127.

83 See Briant, “Michel Rostovtzeff et le passage du monde achéménide au monde hellénistique,” Studi Ellenistici XX (2008): 137–54.

84 See my comments in Briant, History: 1007; also Briant, Rois, tributs et paysans: 505 and n. 41.