3

The darkest of days

ON FRIDAY, 7 February 1997, two weeks before my thirteenth birthday, my eldest brother, Rupert, suffered a serious head injury as a result of a car accident. This has had a deep and lasting effect on our whole family – but mainly, of course, on him. It’s affected each of us in different ways and, I believe, that accident was the catalyst for developing the anxiety that has been a companion throughout so much of my life. In my mind, there’s a clear divide between life before 7 February and life after it. Everything changed on that day, and when I look back I see two different families, two different times, two different worlds.

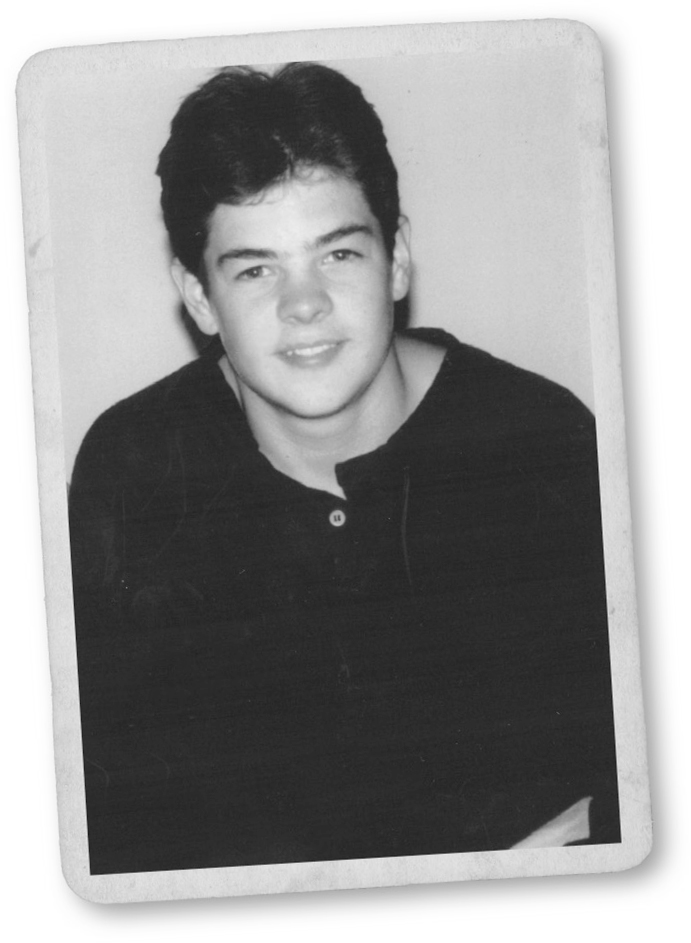

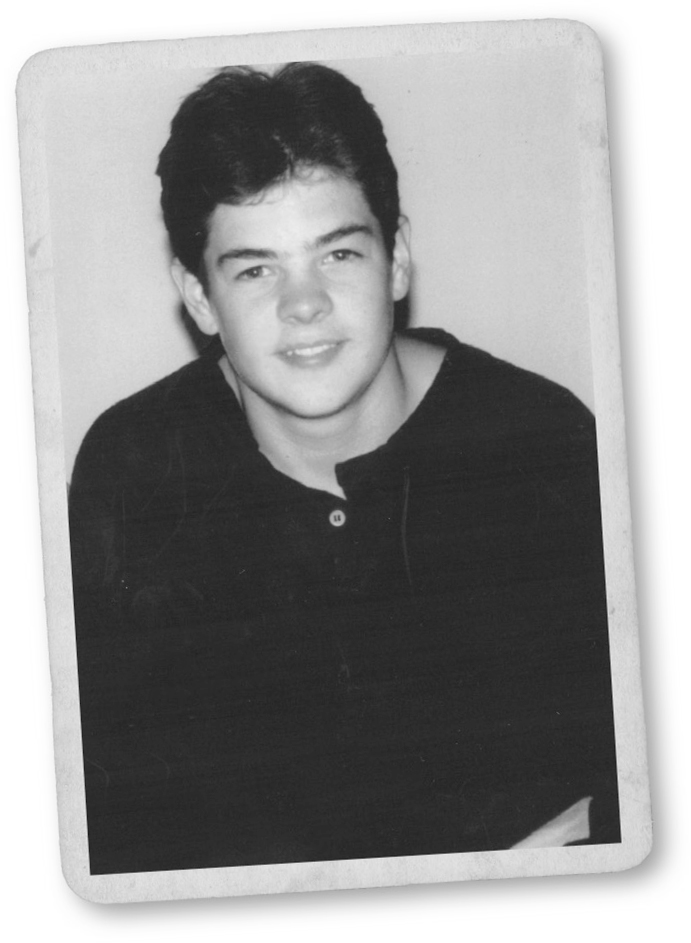

Rupert was eighteen and studying at the Guildhall School of Music in London. He was wild and charismatic, very like my mum in character. Bright, talented, energetic and full of life, everyone at school knew who Rupert was. He was popular, but not always for the right reasons. If something bad happened, Rupert often got the blame, even if it wasn’t him, and he’d often take the blame, even if it wasn’t him. He was vivacious and confident, and you either loved him or hated him. Half his teachers thought he was an amazing life force, the other half thought he was arrogant and needed taking down a peg or two. I know my mum used to dread going to his parent–teacher meetings and the arrival of his school reports, because the comment was always ‘could do better’.

I remember him flying in and out of the house. He never stayed for long as he always had plans – something he wanted to do, somewhere he needed to be. It was Rupert who gave me my nickname of Izzy. My real name is Brittany but when I was young my mum used to say a little rhyme to me: ‘Izzy wizzy, let’s get busy.’ Rupert couldn’t say Brittany, so he picked up on Izzy, and it stuck.

Rupert had a real gift for music. He played the French horn and, unlike the rest of us, barely needed to practise – he was a complete natural, which must have been frustrating for some, and had such great performance skills. Even now, there are people who heard him play when he was still very young, back before the accident, who remember something remarkable about what he was able to do.

He began playing with the National Youth Orchestra when he was fifteen, which is extraordinary as the NYO is very hard to get into, especially for brass players. Spaces are limited and only the most talented make it. Magnus still talks about Rupert playing a big Bruckner symphony as part of the NYO. He had this incredible solo and Magnus says it was the moment everybody was waiting for – the whole room didn’t move for as long as Rupert played. He was a unique and very special musician.

The night of his accident, Rupert had been out with friends in London but had left early, even though his mates tried to persuade him to stay. He was home by around 10 p.m., but came up with the idea that he was going to drive to Wells, his old school in Somerset, that night – two and a half hours away. One of our cousins, whom Rupert was close to, was in sixth form there at the time. It was just the kind of crazy thing Rupert liked to do.

He told Steve, a friend of his who was living with us at the time – the way many people did over the years – of his plan, and Mum overheard him. She was in bed but often kept an ear open for Rupert’s comings and goings. It was already nearly 11 p.m. by then so Mum got up and told him, ‘Rupert, you can’t possibly drive to Wells.’ Of course Rupert reassured her that he hadn’t really meant it and was only going around the corner to see a friend. Mum went back to bed then, and to sleep. But tragically, Rupert didn’t only go around the corner.

He had his own car, an old white Citroën bought with a bit of money inherited from my grandfather, and he drove all the way to Somerset in it that night. It must have been after 1 a.m. by the time he arrived. He saw my cousin for an hour or so and then said he was heading back home to Harpenden. He refused to stay and get some sleep because, he said, he had a horn lesson at the Guildhall later that day.

Many days later, in the midst of the most devastating time of our lives, we learned that Rupert’s music teacher had rung and left a message on his phone to say the lesson was cancelled. But Rupert’s phone was out of battery and he never got the message. We listened to that voicemail afterwards, and that was one of the hardest things – knowing there had been no reason for Rupert to leave Wells that night. He could have stayed. He could have been safe. All of our lives could have been different.

There are so many ‘what ifs’ and ‘if onlys’, but we would send ourselves mad if we thought too hard about them.

From what we know, Rupert left Wells at about 3 a.m., and he got to the junction joining the M25 and the M1 sometime around 5 a.m., at which stage he was only about ten minutes from home. The exit is a stone’s throw from where he crashed. He so nearly made it.

He drove into the back of an articulated lorry. We think he probably fell asleep at the wheel but we’ll never know. He could have been fiddling with his stereo, or reaching for something. His car went underneath the lorry and was torn up like a tin can. The M25 was shut; fire engines, police cars and ambulances arrived. Rupert had to be cut out of the wrecked car. He was dead at the scene and only brought back to life by a defibrillator. It’s a miracle that he survived but we’ve sometimes asked ourselves whether his survival was a good thing. It’s a terrible question to ask, but with everything that followed, I think my parents have thought, at times, that perhaps it would have been kinder, given Rupert’s quality of life now, if the tragedy had begun and ended that morning on the M25.

For Mum and Dad, the first they knew about the way in which all our lives had changed was when the doorbell rang very early in the morning, when all of us should have been in the house and safe asleep. At first, my dad thought it was Rupert, and that he’d forgotten his keys. When he saw the police, again his thoughts went straight to Rupert. Dad assumed Rupert had done something and was in trouble. But when the officers quoted the car registration number, asking Dad if Rupert was the owner of the vehicle, Dad knew instantly that something was terribly wrong and he fell to the floor in a state of shock.

My mother’s first reaction was to say that she hoped Rupert hadn’t broken his arm, because he was due to play in a concert at King’s the following evening with my other brothers.

I remember the moment I heard about the accident so clearly. I’d slept in my own room that night, and early in the morning Mum opened my bedroom door to let me know what had happened. She explained that she and Dad had to go to the hospital and I’d have to get myself off to school. I remember hoping Rupert hadn’t hurt himself too badly, but not being too alarmed. In fact, those were probably the last innocent thoughts of a young teenager who knew nothing about loss or grief. I had no idea how much our lives were about to change. I just went back to sleep until my alarm went off and it was time to get up as normal.

Mum and Dad were driven to the hospital by the police, who were unable to tell them much about what had happened, or even how Rupert was. Steve, Rupert’s friend, was at home so I wasn’t alone, and we just presumed at that stage that Rupert was going to be OK. About an hour after my parents had left – it was still very early and I hadn’t yet gone to school – the phone rang. It was Mum, letting me know that a police car was coming to fetch me and take me to the hospital. I grabbed Rupert’s beloved Snoopy teddy, as I hoped it would cheer him up. I imagined him sitting up in a hospital bed, getting better from his accident, with Snoopy keeping him company.

When I got to the hospital, Mum and Dad were sat in a tiny, dreary family room, their chairs pulled close to each other for support and their shoulders hunched. Seeing them there, I immediately understood that something was very wrong. I’d never seen them looking like that before – the emptiness in their eyes and fear in their voices was terrifying. It was as if my pillars of strength had crumbled. They weren’t crying – I think they either didn’t dare allow themselves to, or were perhaps in too much shock – but it was as if they weren’t quite there. I remember trying to take it all in but feeling completely lost and frightened. I just wanted to go home and then to school, where life would be normal. I wanted what already felt like a terrible nightmare to end.

Mum and Dad hadn’t even seen Rupert at that point – the nurses had advised them not to go in because of how very badly he was injured. The head injuries he’d suffered were catastrophic and he was on life support. So they’d just been sitting in that room, passing the phone back and forth between them, ringing various people to tell them the terrible news. Neither of them could really complete a sentence, so they took it in turns to try to deliver the information, which they barely understood themselves, to family and friends.

Instinctively I wanted to help, so being upset wasn’t an option in my mind. I wanted to do something to fix things, to make them feel better, and the only thing I could think of was to offer to fetch them tea and coffee.

I remember a nurse coming in and saying, ‘We’re going to wheel Rupert past.’ They were moving him to a different hospital called Atkinson Morley, in Wimbledon, which specialized in neurology and neuroscience. I wanted so much to see him, but the nurse said it was best I didn’t because he was too ill. So I asked her to give him the Snoopy, because I wanted him to have something from home.

Since the day I was born, I’ve had a Winnie-the-Pooh bear that has always been such a comfort to me, and I hoped Snoopy would be the same for Roops that day. The nurse was very kind and said she would give it to him, but really I wanted to do it myself. I remember being so confused as to why I couldn’t see him, and when I handed Rupert’s Snoopy over to the nurse, I suddenly wanted it back; I realized it had been comforting me.

For all the strangeness of the hospital, I only really began to understand how very bad things were once we got home and I started to pick up on the atmosphere of fear. Even though I was thinking about Rupert, I was more sensitive to what I could see around me, and that was Mum, Dad, Magnus, Guy and my granny. I was very tuned in to them and their reactions. I was certainly being protected from the full story, but I had an intuition that I wasn’t being told everything.

I remember being sat on my granny’s knee and asking her if Rupert died whether he’d be with my grandfather. The thought of him going to heaven gave me comfort, as I knew he’d be safe there. My granny was the real matriarch of the family, and she and I were very close. She was the anchor, the person who held it all together. She’d been through so much herself – the war, losing her husband, siblings and friends – and she was so strong that she gave me hope that everything would be OK.

About a week after the accident, during which time Rupert remained on life support in the intensive care unit, he had brain surgery – a twelve-hour operation followed by every conceivable type of setback. First he contracted MRSA. Then one of his lungs collapsed. Then he got pneumonia, followed by a cranial fluid leak, which meant more surgery and a tracheotomy – which is where they make an incision in the windpipe to relieve an obstruction to breathing. But Rupert is such a fighter.

He contracted pneumonia on my thirteenth birthday. I’d been looking forward to this birthday so much – I think any girl’s thirteenth is exciting. I was having a disco with friends in the hall of my parents’ music school. However, before the party got under way, Mum told me that Rupert was unwell and they had to go back to the hospital. The party still went ahead but without my parents there. I remember feeling irritated that they’d gone, that I couldn’t even have just this one day. Perhaps because Mum and Dad tried so hard to make sure life went on as normal for me, I wasn’t fully aware of just how bad things were.

The first time I saw Rupert after the accident he was still in intensive care, wired up to so many machines, which he hated – they had to put the blood-pressure monitor on his toe instead of his finger because he kept tearing it off. I remember the ICU so clearly – it was somehow peaceful, despite the near-constant beeps from the machines. Sometimes, in between the noises, I could even hear the clock ticking on the wall behind the nurses station.

The other patients around Rupert were also in very serious conditions. I was both too young and too old to cope well with that; too old not to understand what was happening, but not yet old enough to comprehend the full implications. I so badly wanted to do something, anything, to help and to make people feel better, but there was little I could do.

When tragedy happens, the world seems to stop, but soon enough a normal kind of life resumes. The trauma doesn’t go away, so you learn to live around it. At a certain point, those who have visited with food and flowers have to go back to their own lives but you’re still left with a terrible new reality. That’s when you know – really know – who your true friends are, because they’re still with you. And we were lucky. We had many true friends.

The doctors couldn’t tell us much immediately after the surgery, as at that stage they had no idea exactly how much damage had been done. The hope was that the parts of Rupert’s brain that hadn’t been injured would gradually learn to take over the functions of those that had been, and that Rupert would start to re-learn any skills he’d lost. They told us this could take up to ten years.

At first Rupert wasn’t able to communicate at all. The tracheotomy meant that he couldn’t talk, and there were very few other signs of response from him. The only real sign of life, or memory, came through his reaction to the classical horn music we played to him. One day we even gave him his French horn to hold. He couldn’t play it, of course, but he started to move his fingers in time to the music. That was the first indication we had that he recognized something, that somewhere in there the Rupert we knew was trying to communicate with us.

In the months following his operation, progress was evident every day. He slowly started to learn to walk, to talk and to feed himself again. But it got to a point, about a year later, once he’d re-learned these basic life skills, that it became a question of seeing how much more he was going to improve, and what his permanent cognitive injuries would be. Today, twenty years down the line, we’re definitely at a point where we know there won’t be any further recovery. For a long time, we were watching every day, desperately hoping, but then I think we slowly began to realize that he wasn’t going to get any better than he was. Although the realization was gradual, it was very painful.

We’d hoped for a miracle – that Rupert would return fully to himself. Beginning to accept that that wouldn’t happen meant saying goodbye to the Rupert we had known, and mourning the person he could have been. It’s still something we experience every day. I don’t think we’ll ever fully come to terms with it.

For many months, Rupert’s bed stayed exactly as I had found it on that first morning, because Mum couldn’t bear to go into his room. The room continued to smell of Lynx Africa, and his Charles Worthington shampoo stayed in the bathroom, even though no one else ever used it. For a long time, we expected him to come home, and so everything stayed right where he’d left it, waiting for him.

Although Rupert did come home briefly after his long stay in hospital, my parents quickly realized that they couldn’t cope with him living there. It was a difficult time as we were all in a state of confusion about Rupert’s needs and how best to look after him day to day. Eventually, after much thought and advice from local services, it was decided that it would be best for Rupert to move to a residential home for rehabilitation and ongoing care. I can only imagine now what a heart-wrenching decision that was for my parents to have made.

Today, Roops is basically an exaggerated version of the person he was before the accident. You never forget meeting him! He walks into a room and people are immediately aware of his presence. His behaviour is very friendly and he’s immensely loving and giving, but he can often be inappropriate because he has no awareness of boundaries or personal space. He’ll sometimes shout at the top of his voice in crowded places, or get up and begin walking around when it’s not appropriate to. He can’t settle to any occupation for very long and constantly wants to know what’s happening next. He lives in either the past or the future, but finds it difficult to be in the moment.

What’s almost more frustrating is the fact that he is so nearly there. He’s capable physically, engaging, understands nearly everything and knows who everyone is. He can still play music beautifully and take part in conversation. There’s just something missing, a layer of awareness. He’s childlike, but in an adult’s body, with adult language, adult strength and some adult knowledge.

He’s also very conscious of what he doesn’t have. Major life events have a profound emotional effect on him because he understands that they may never happen for him – he’s unlikely ever to get engaged or married or have a family, and he’s deeply saddened by this. As are all of us, for him.

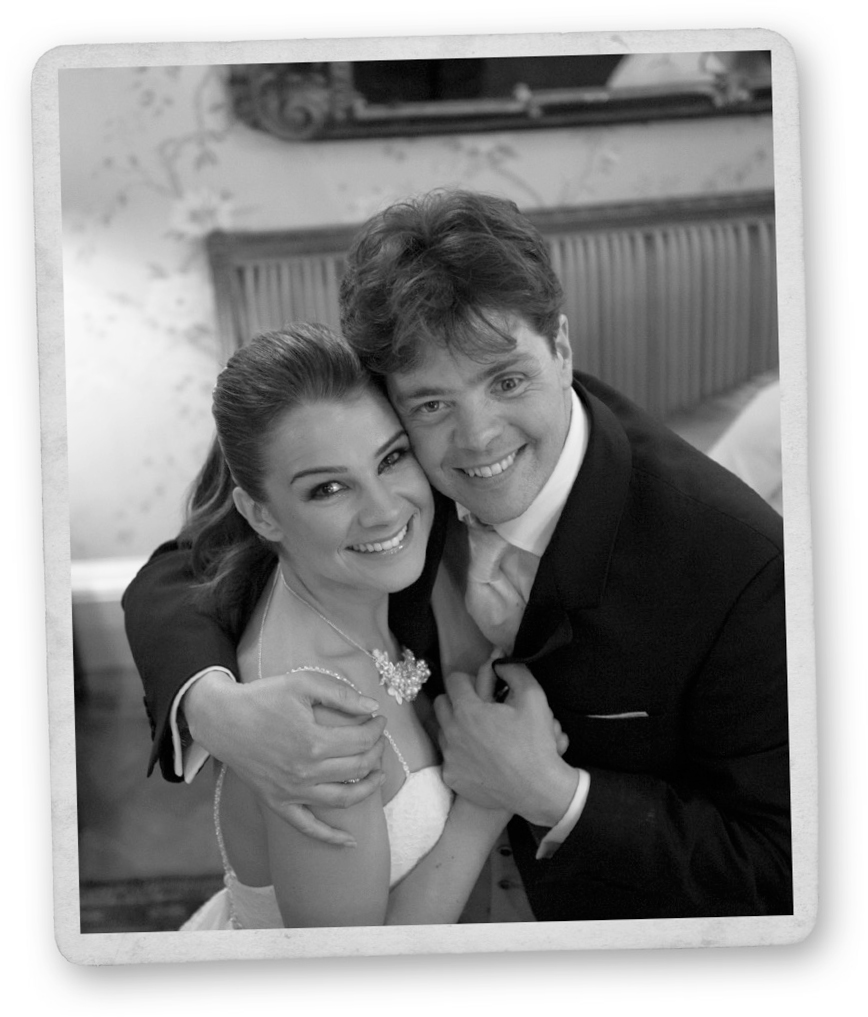

When I accepted Harry’s proposal, I felt so guilty when I thought about Rupert. I’m so lucky to have Harry and it seemed incredibly unfair that Roops may never experience the same feelings of love and happiness, as he’s such a warm and loving person himself. In so many ways, Rupert’s life stopped the day of his accident.

Mum was very worried about how Rupert would behave on our wedding day. She was concerned that he would be disruptive in some way, such as coming up to the altar during the service. There had been discussions about him being there just for the ceremony, missing the reception and returning for the evening celebrations, but I insisted that he stay for the whole day. I didn’t mind if he was disruptive – as far as I was concerned, he was welcome to stand with Harry and me throughout the whole ceremony if he wanted to. I wanted to make him feel it was his celebration as much as mine. ‘After all,’ I thought, ‘if he can’t be himself on my wedding day, when can Rupert just be Rupert?’ And he was brilliant. He played his French horn during the service, and of course made the most of his moment, coming out and taking a bow before the congregation. Then, during the after-dinner speeches, he was even heckling with one-liners, making everyone laugh.

But it was very hard too, for all of us, because even though Rupert was happy for me, and happy to be there, he was terribly emotional. My brothers Magnus and Guy played as I walked down the aisle – ‘Gabriel’s Oboe’ from the film The Mission – and in the recording, on the wedding video, you can clearly hear Rupert sobbing. I can’t listen to it without wanting to cry for him.

Rupert has so much to offer but we all still grieve for what we’ve lost. His music career, which was so promising, tragically never materialized. He requires twenty-four-hour care, can’t lead an independent life and never will. We love the person who is here now, of course we do – he’s our brother, my parents’ son – but it’s impossible not to wonder sometimes about what he might have been had this never happened.

That was the reason I later set up the Eyes Alight appeal, to raise money for victims of brain injury. To try to give Roops back a little something of what he had lost. And because my way of dealing with the sad and terrible things that sometimes happen is to try to make something good come out of them. It’s the same impulse that later made me want to be honest about my IVF experiences – the idea that I could help others, and that the hard times I went through could somehow be turned into something positive.

Twenty years ago, my family’s life changed for ever. I’ll remember every second of 7 February 1997 for the rest of my life. It is through tragedy that you discover so much about yourself and others. It changes the way you look at life. You learn who will stay by your side to help you through the difficult times. There’s a handful of truly special friends to Rupert, the ones who still visit, answer his endless phone calls and brighten up his day. These people are amazing and I don’t think they realize what their kindness means to my family and, of course, to Rupert. Harry has become a best friend to him – he loves him unconditionally and that’s just so special. He reminds me to take Rupert for who he is today – a unique, inspirational and awesome brother. I couldn’t imagine my life without Rupert in it.

Through my darkest times when my anxiety was unbearable and my desperation for a baby was taking over my life, somehow Roops always seemed to be sitting on my shoulder, reminding me to keep things in perspective and try my hardest to make the most of each day. This isn’t always easy, of course, but I’ve tried my best. I feel I owe that to him and the fight he put up for life. But most importantly, Rupert has taught me to celebrate life, family, friends, love and everything we have to live for.