WITHIN MINUTES OF the Louvre closing its doors to visitors in the early evening of Friday, August 25, packing began. From all corners of the museum, workers removed the top-priority movable paintings, antiquities, and objets d’art—from religious relics to furniture to the crown jewels—from walls, pedestals and cases. As paintings were removed, first from the walls and then from their frames, workers marked the empty spaces with chalk to note their location to facilitate rehanging upon their return.

Workers took items along the carefully planned routes to designated triage areas where others wrapped and crated them, then nailed the crates shut, sealed them and applied more colored priority stickers. The tasks were all the more difficult after dark since workers had only the dim light of small portable lamps, a precaution in case of a bombing raid.

By 1 a.m., all fifty or so of the most prestigious paintings considered readily movable had been moved to the triage areas. Workers then rushed back to the galleries to begin the next round. The atmosphere was frenzied, but the packing went smoothly; every part of the endeavor had been analyzed again and again over multiple years and then rehearsed.

THE LOUVRE’S RUBENS GALLERY EMPTIED OF PAINTINGS

With the military draft underway, it had been a mad scramble for Jaujard to assemble the small army of people needed for the massive operation. Museum staff members were called back by telegram from their August holidays. Museum guards—most of whom were men injured in World War I—helped out alongside curators, technicians, professional packers and movers. Jaujard had obtained approval from military leaders and other authorities to use civilian volunteers. Among those helping out were dozens of men on loan from several of the big Parisian department stores, including the Samaritaine, whose owner, Gabriel Cognacq, was vice president of the National Museum Council. At one point, young staff member Magdeleine Hours walked into a gallery to find men from one of the department stores packing up fourteenth- and fifteenth-century paintings. Like the other workers, they were dressed in long work smocks, but they also wore mauve tights and striped caps. Hours was stupefied; they looked to her just like characters in the medieval works they were packing.

WORKERS PACKING UP PAINTINGS, AUGUST 1939

In the triage areas, antiquities were packed in protective material. Smaller paintings were wrapped first in fire-resistant paper, then in leatherette to resist humidity; fiber spacers separated multiple paintings packed in a single crate. Dust swirled in the air and hammers clattered as typists furiously tapped out quintuplicate lists of the contents of each crate. To disguise the contents of crates, they bore only three markings: the initials “MN,” the department initials and a crate number; the anonymity was intended to discourage theft and to frustrate searches by Germans. Moreover, to keep unauthorized individuals from knowing where the items were going, all shipping labels said Chambord, even though many items had already been assigned to other final destinations in the Loire Valley.

The official evacuation order came on Sunday, August 27, after two days of around-the-cl0ck packing. The Cour Carrée was closed to the public and empty trucks began rolling into the courtyard; Jacques Jaujard presided over the loading and verification operation. By evening, the first trucks were ready and waiting for departure early the following morning. The Mona Lisa, carefully wrapped in layers of special paper, set into her special velvet-lined case and packed in her own crate, was aboard a truck with thirty-one other crates. These other crates, according to procedure, bore the initials “MN,” the department initials and a crate number. Not so for Mona Lisa’s crate, which for additional security during the trip had been vaguely marked simply “MN.” Jaujard handed the convoy leader a handwritten note to be handed to Pierre Schommer at Chambord. “Truck Chenue 2162RM2,” Jaujard wrote, “contains a crate marked MN in black without letters or numbers. This crate contains the Mona Lisa. Mark it LP0 in red.”

At 6 a.m. on August 28, 1939, the first convoy of eight trucks, loaded with the Mona Lisa, the Seated Scribe, the crown jewels and 225 other crates of some of the world’s most precious art and antiquities rolled slowly away from Paris towards the French countryside.

TRUCKS LINED UP ALONG THE SEINE, MUSEUM AT RIGHT

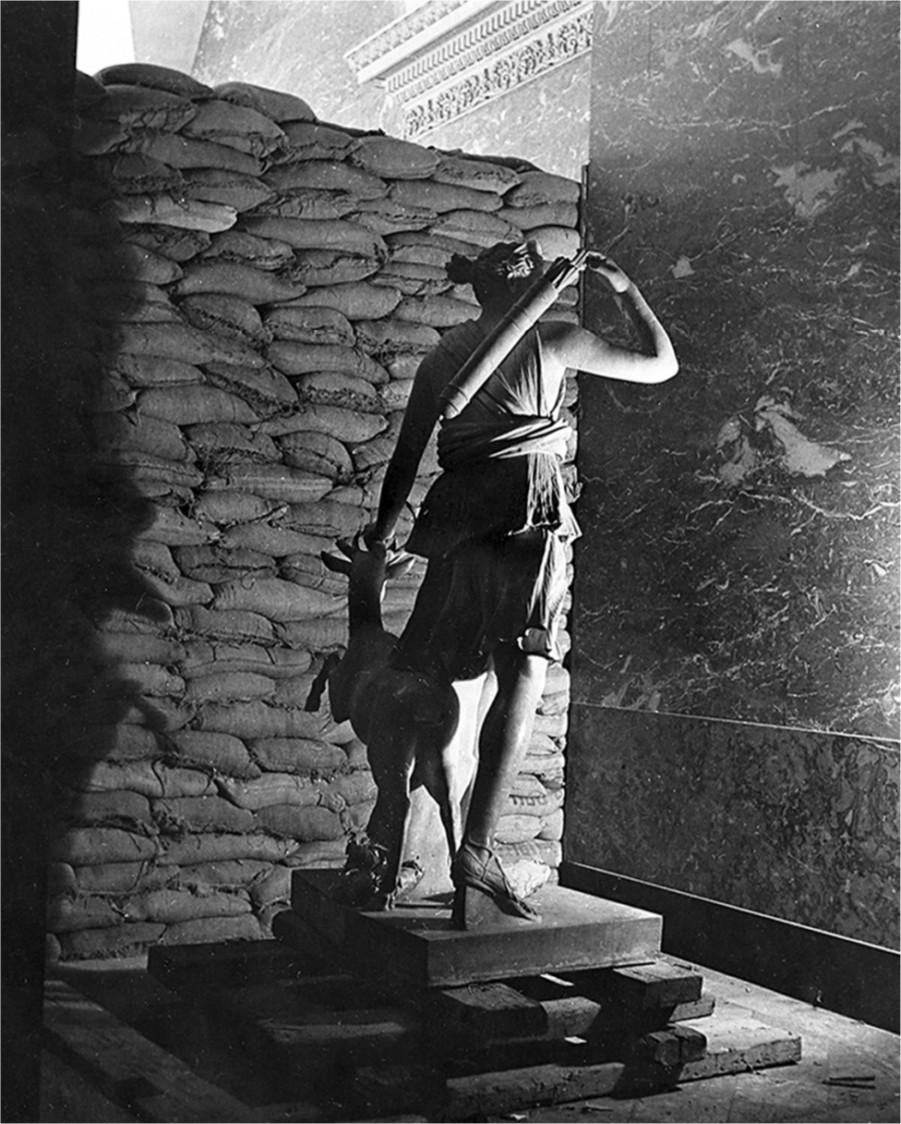

Six additional trucks were loaded that morning; they left in a second convoy at 2 p.m. By the following day, the pace had picked up, with twenty-three trucks leaving Paris. As soon as trucks returned empty from the Loire, they were quickly loaded again. Two convoys left each day until September 2, when only one convoy of nine trucks headed south. Not all evacuated items went to the Loire; between August 28 and 30, several dozen of the museum’s best pastels deemed too fragile for a long journey, among them Boucher’s Madame de Pompadour and seven works by Degas, were moved to the two climate-controlled underground vaults at the Banque de France that had been leased the previous year. Many works did not leave the museum at all. Those items deemed too fragile or heavy to move—like the ancient sarcophagi, Venus de Milo, Artemis with a Doe and Michelango’s Slaves—either remained in place or were moved to areas deemed strong enough to withstand the force of a bomb; sandbags added additional protection.

ARTEMIS WITH A DOE DURING THE WAR (1ST–2ND CENTURY AD)

LOUVRE, SULLY WING, GROUND FLOOR, SALLE DES CARYATIDES

In the pre-dawn hours of September 1, as 1.5 million German troops began pouring into Poland, workers in the museum picked up the pace even more. On September 1 and 2, they worked through the night as war became more inevitable by the minute. By then, they had turned towards the challenging task of evacuating the very large paintings. The Louvre’s largest painting of all, the Wedding Feast at Cana, was removed from its chassis and rolled onto a giant oak column; David’s giant Coronation of Napoleon was also rolled. Too long to fit in a truck, these and other rolled paintings were loaded onto huge scenery trailers loaned by the Comédie-Française.

Moving the giant Raft of the Medusa—22 feet wide by 16 feet tall—caused unique problems. Géricault had used bitumen, used in making asphalt, in large areas of the painting to achieve a saturated black. Because the sticky material never completely dries, the painting could not be rolled and its massive height made it a challenge to transport since the convoy would have to pass under bridges and utility wires.

The route was carefully studied. Arrangements were made for agents of the French post office and telecommunications agency to precede the convoy with insulated poles that could temporarily disconnect telephone and telegraph wires to allow the convoy to safely pass. Even the weather report was consulted to be sure the depiction of sailors and their sails would not itself be cast adrift by heavy winds.

Reassured—or so they thought—of the painting’s safety en route, the convoy, which included other large nineteenth-century paintings, set out in the early evening of September 1. Daytime travel would have been easier, but the scenery trailers could crawl along at only eleven miles per hour and evening travel would cause less disruption to traffic.

Except for a detour around the viaduct at Passy, which did not provide sufficient clearance for the combined height of the Raft and the scenery trailer, the convoy passed uneventfully under the other bridges from Paris towards Versailles, one of the towns along the route to the Loire Valley. But as the convoy passed the Versailles town hall, the museum staff suddenly heard loud crackling, giant sparks flew everywhere and the Raft’s trailer was thrown sideways. The route planners had not taken into account overhead trolley wires, into which the giant painting had crashed. As sparks lit up the night, electricity to the entire town had to be shut off, plunging the town into darkness and setting off panic among residents, who thought surely it was a German attack. Curators feared not only a fire, but also rioting by the angry mob that gathered around the convoy. To the curators’ surprise, the painting was not damaged. René Huyghe, curator of the Louvre’s Department of Paintings, later commented that it was “unthinkable that after having escaped the furious sea, the Raft would fall victim to flames.”

RAFT OF THE MEDUSA LEAVING THE LOUVRE, SEPTEMBER 1939

As the scene calmed, the convoy leader realized that the continued presence of the Raft could cause similar problems along the rest of the route. He sent Louvre curator Magdeleine Hours to ask the curator at the nearby château de Versailles if he would shelter it and the other paintings on the trailer until other arrangements could be made. Hours spent more than a quarter hour in the pitch-black darkness feeling her way bar by bar along the château’s closed gates before she finally found the bell. Her repeated ringing received no response. Finally, the curator appeared in his nightclothes; he had gone to bed early to be ready for an evacuation at dawn of some of the château’s own artworks. He opened the gates wide for the large scenery trailer loaded with its even larger artwork.

After hearing about the day’s debacle, Jaujard changed the route for the next shipment of large paintings scheduled to head to Chambord. He was concerned not only about more potential wire problems, but also whether the other large unrolled works, and even the rolled Wedding Feast at Cana, would fit through the low entry to the Chambord courtyard. He decided that the newest shipment of large works would join the others at Versailles for several weeks as a temporary measure until the administration could find safe routes directly to the châteaux that would host the paintings, bypassing the Chambord way station altogether. When they were finally moved to the Loire Valley, the 100-mile journey would take sixteen hours.

MOVING WINGED VICTORY OF SAMOTHRACE (1945 RETURN)

By the morning of September 2, the Louvre had already removed every item on the three top-priority lists. While workers packed yet more items and protected those that would remain, Jaujard faced another unexpected challenge: bringing the 9-foot-high, 3.5-ton Winged Victory of Samothrace down from the top of the soaring Daru staircase. Curators had originally considered the statue impractical to move, but believed sandbags and the vaulted ceiling above could adequately protect it. However, a subsequent examination indicated the ceiling was, in fact, not strong enough to withstand a bomb impact. On September 2, using a thick pulley, chains and ropes mounted to a huge wooden frame constructed around the statue, the Winged Victory—made of 118 pieces, some just fragile plaster replacements—rose slowly from its base and onto a specially built wooden ramp, along which it was slowly inched down the fifty-three steps of the staircase while a small group of staff members watched, holding their collective breath. Once it had safely reached the ground floor, the statue was moved to a vaulted wall recess supported by giant pillars and covered with a thick barrier of sandbags.

ANCIENT STONE SLABS IN LOUVRE UNDERGROUND SERVICE CORRIDOR

A last pre-war convoy left on the evening of September 2. By then, dust-covered workers had toiled around the clock for days, catching brief naps in the museum. By that point, ninety-five truckloads had carried away more than 1,200 crates of the Louvre’s treasures. As in previous wars, items deemed too fragile or heavy to evacuate had been brought down to the ground floor and the basements, many protected with sandbags. Some were tucked into vaulted recesses or other safe areas, while others were stacked along the endless underground service corridors.

WORKERS MOVING VENUS DE MILO (1945 RETURN)

The only items remaining in the largely deserted museum were items of lesser value, including 600 paintings, plus works deemed too fragile or large to move, including the Venus de Milo and the Winged Victory of Samothrace. These two items would not remain for long.

On September 3 at 9 a.m., England issued an ultimatum to Hitler that it would declare war if it did not hear within two hours that Germany was prepared to withdraw its troops from Poland. At noon, France issued a similar ultimatum expiring at 5 p.m. At 5 p.m., France declared war on Germany. No trucks left the Louvre that day. Almost ninety percent of the museum’s paintings were already gone; the only trace of them was white chalk marks on gallery walls and empty frames on the floors. The majority of the transportable antiquities and objets d’art were also gone, tucked away safely—or so it was hoped—at Chambord and other châteaux of the Loire.

Paris waited in dread that night for German bombers, but none came. The following night, the city’s residents heard the sirens of an air raid alert, but again there was no sign of German planes. Nor did they come in the days that followed. By September 6, the Louvre administration felt it safe to begin evacuating—on a far smaller scale—still more items of lesser importance. However, on September 20, Jaujard and the Commission of Historic Monuments and Buildings concluded that the important large sculptures still in the Louvre were not safe enough. In the first days of October, a twenty-ninth convoy left from the Louvre, this one heading to the Loire Valley château de Valençay. It carried the Venus de Milo, the Winged Victory of Samothrace and Michelangelo’s Slaves, along with 2,400-year-old frieze fragments from the Greek Parthenon and Houdon’s eighteenth-century bronze sculpture, Diana.

Just over a week later, restoration specialists balanced on shaky scaffolding that reached almost to the top of the 45-foot-high galerie d’Apollon while they removed Delacroix’s Apollo Slays Python from the room’s ceiling. The large work was then rolled onto a long custom-made wooden cylinder. René Huyghe was not happy about the rolling since it could cause the paint to crack, but he knew there was no choice.

Smaller convoys continued to remove items to châteaux in the countryside. By the end of October, more than 2,000 crates filled with treasures had been removed from the Louvre in more than 200 truckloads. The museum had been emptied of 3,691 paintings plus many thousands more antiquities, engravings, drawings, sculptures, and objets d’art. Sixty percent of the herculean task had been accomplished in the six days between August 28 and September 2, and ninety-two percent of it all by the end of September. Virtually all the rest had been removed before the end of October.

In addition to orchestrating the massive evacuation at the Louvre, Jaujard also supervised the evacuation of 465 crates from the Cluny, Luxembourg, Jeu de Paume and other Paris museums under the jurisdiction of the Musées Nationaux, 599 crates from Versailles and the other non-Paris national museums under its control, more than 1,400 crates from the Musée des Arts Décoratifs and other public institutions, and almost 600 crates from private collections, most belonging to prominent Jewish collectors.

With most of the Louvre’s treasures spread across the French countryside, nobody knew how long they would stay away. In fact, they would not start heading home for almost six years.

THE LOUVRE’S GRANDE GALERIE, EMPTIED OF ITS ART