— PROFILE —

by Ted Butchart, GreenFire Institute

Architectural design is always a matter of juggling a great number of competing and even conflicting imperatives. Rare is the project that allows a designer to give flight to all his or her sculptural and tactile longings, because the more subtle aspects of a design often must give way to more prosaic, but far more practical, considerations. Anne Thrune’s project was that rare exception for me.

Anne came to me with a simple request. She wanted a small building to house her massage and healing practice, and to function as a short-stay retreat for a person wanting some concentrated introspection time. Functionally, the list of requirements for this project was much shorter than that of a typical house design. It only had to provide a small arrival space for a waiting client, a changing room with toilet and shower, and a main room for massage and other healing work. Certainly less demanding than a house, with its stipulations for eating, cooking, entertaining, noisy areas, quiet areas, and so on, the relative simplicity of this program allowed us to go quite deeply into the subtle needs of the space.

I have had two principal threads of fascination through my life—architecture and medi-cine—and all my divergent interests weave back into those primary plaits. I approach my design work as medicine, be it houses or healing spaces; and I often ponder what it is that makes a space conducive to therapies. Foremost is the ideal of a safe and sheltering space that will support a patient’s healing work. I believe that as designers we must grapple with the more subtle aspects of health, and in building design our work should reflect the shift toward empower-ing the patient and toward the emotional and spiritual content of the space. Although my “medicine” is oriented toward built space, it springs from Chinese and Tibetan medical thinking, and the overlap with Anne’s medical models gave us a common vocabulary. The trust that quickly formed between us was an important key to the success of the final product.

My approach to the building was guided by the experience of a person receiving a massage. I wanted that experience to flow from a feeling of complete safety and security. To fully relax, physically and emotionally, we have to know that we are safe and this building had to communi-cate on many levels that “here was sanctuary.” Straw bale walls are ideal for that; their thickness makes the person inside feel invulnerable, the walls are highly soundproof, the reflected sound is soft, not harsh, and the stucco exterior adds yet more to the feeling of complete safety.

Another important part of the experience is what the client sees and feels while lying on the massage table. Assuming we don’t immediately fall asleep, the visual field can be important. A boxy room with a flat white ceiling and sharp corners can actually interfere with drifting into deeper states of relaxation. The eye is constantly stopped, or pulled repeatedly to some bland view. This is emotionally neutral at best, if not annoying, and the only option is to close one’s eyes. I wanted a space that was somehow myste-rious, that pulled the eye toward unusual patterns and engaged the right brain more than the left. I believe that where we enter into psycho-therapies, somatic therapies, or any emotional and spiritual healing, the space should be visu-ally complex, but never jarring. Smooth curves and complex ceiling planes allow the logical mind to wander, giving the other aspects of con-sciousness a chance to come to the fore.

I rolled these ideas around in the back of my mind for some time as I played with various designs for the building. One day Anne traded me a massage session against some design time. She is a multitalented practitioner, and as I lay on the table slowly melting into a pool of limpness and relief, I focused on the tendons and verte- brae of my neck that she was delineating. Suddenly I had the answer, or at least a vision that I could attempt to replicate in the new building. I wanted to have the building reflect the work she did: cleaning up the interplay between the bones and the tendons, or in my case, the posts and the beams. The net of tendons became a complex ray of beams, and the spinal column became a steel-ring-bound cluster of thin cedar poles making up the center support post. The brief image there on the massage table also showed a wonderful quality of light filtering down through the “tendons” of the roof. As I chased this idea it evolved into a multilayered roof with thin windows filling the space between the layers. This would allow light to enter at the top of the space and directly illuminate the wood of the ceiling, drawing the eye upward.

The problem of daylighting the space was only partly solved by the roof windows. A more critical problem was placing windows so that daylight would enter, but privacy would be preserved. Anne’s property is forested, and it is large enough that the chance of anyone peeping in through the windows is fairly slight. But when it comes to the experience of feeling secure, the perception of safety is far more relevant than the reality. For the space to work on all the levels that we desired, we needed win-dows that would allow us to connect to the natural world outside, yet would not require curtains to prevent any imaginary peeping Toms from peering in. The answer came while juggling yet another subtle need: the desire to have the building quetly acknowledge the presence and the importance of the client.

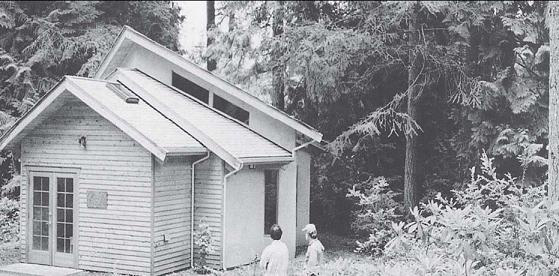

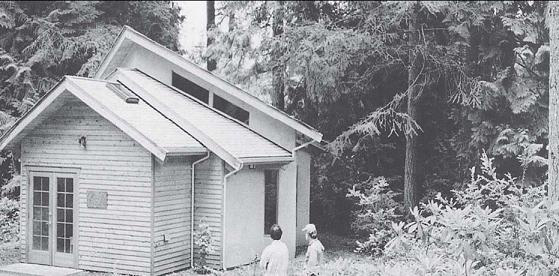

Anne Thrune’s massage studio, designed by Ted Butchart of Greenfire Institute.

This may sound odd at first reading. How can a building acknowledge a person? It can, and builders have been using perceptual tricks to do just that since classical times. It is a subtle conversation based on how we perceive space. If a building swells out toward you with a convex surface it is subtly indicating that you are not important. Something on the other side of it seems to be “pushing it outward,” and your tiny presence has no counter “push.” However, when a wall falls away from you in a concave form, just the opposite is being stated in its form—your side of the wall is “pushing” it away to create space and the building is respectfully backing away. If you have seen a picture of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, or happily had the chance to experience it in person, perhaps you remember the grand out-curving colonnade that surrounds the plaza in front of the cathedral. The great curves seem to have been placed to surround and envelop a great crowd of people and their presence in that plaza is important and articulated even when the crowd is absent. The colonnade is being pressed back by an unseen force.

The windows on the Thrune massage studio are oriented to provide privacy for the people inside.

Generally only important civic spaces engage in that sort of interplay. But on a rural, forested lot, what is to prevent us from acknowledging these subtleties? The activity inside Anne’s studio is critically important to the participants as they struggle with healing physical and emo-tional wounds, or delve into the hidden vistas of their spiritual landscapes. The individual has a “personal space bubble” around them, and the social act between healer and patient creates a virtual space bubble that is a great deal larger. We can acknowledge that social space, and very subtly support the act, by allowing the walls to flex outward and mark the edges of the space. The presence and innate worth of the client is visually marked.

I realized that this concept of acknowledgment offered an elegant solution to my problem with the windows. Even a straight bale wall is much more sensual than a boring old wallboard wall, but a curved bale wall is a wonder of sensuality and texture. And the best way to light such a wall is with a glancing light across its face to highlight the subtle variations on the surface. If we were to step the curved walls out and insert a tall thin window in the step-out, we would get exactly the right sort of light and a high degree of privacy, too. In this design, the windows are set on the radius of the building, always at right angles to, and invisible from, the massage table. As the sun progresses through the day there is a constantly changing play of light and shadow on the wall.

Externally, the building is composed of two different materials: stucco on the bale walls and cedar on the standard stud walls that make up the entrance and changing rooms. The cedar walls reflect the forested setting and harken back to the older cultural history of the area. From one vantage point, if you know where to look, the public face of the building makes a vi-sual allusion to the traditional Long Houses of the coastal Indians, an attempt at respecting the history of the place without overtly mimicking another culture’s forms.

For the technically inclined, I offer a brief de-scription of the structural system. Although I have designed straw bale buildings with every imaginable structure, my personal preference is for a system that allows the straw bales to be used as flexibly as possible. I often set structural piers outside the bale wall so that the bales can be set both more rapidly and in any curved form I desire. In the case of this studio I did not want the outer posts exposed, I did not want to use concrete or cantilevered posts to take the lateral forces, and we did not then have the engineer-ing test results to justify using the stucco skin as the lateral bracing system. What we came up with were basically box columns, sufficiently stiff and sufficiently anchored to the concrete foundation to resist movement in the plane of the supported beam. These box columns formed the end of each curved segment of wall (18 inches), included the thin window between the segments (12 inches), and formed the start of the next segment (another 18 inches). So each was approximately 4 feet wide. These boxes-columns, arrayed around the north side of the building, combine with the standard plywood-braced walls on the south side to sufficiently stabilize the building in this high-seismic zone. The great strength of the stucco walls, as is often the case with straw buildings, simply offers a very high level of backup.

Central load-bearing column, where the main rafters converge.

Floor plan.

The interior of the building was finished as naturally as was possible. The floor was intended to be a troweled-on earthen floor, but a lack of suitable material on Whidbey, a glacier debris island, eventually caused us to switch to a concrete slab floor. The radiant heat in the floor works perfectly with the high insulation level of the straw walls, and the brownish acid-wash coloring on the concrete gives a remarkably “earthen” look to the floor. Where Anne must stand to work around the table she has a circu-lar carpet to soften the concrete. The walls are covered in a pure white clay plaster, which further softens the straw walls acoustically. The exposed beams and wood decking of the ceiling were flamed and brushed to seal the surfaces and highlight the grain without the use of chemical sealers. Excellent local craftsmen created fine detailed doors covered with split bamboo to bring the scale of the studio down to the very small where people would approach it most closely.

The final space is meditative and exudes what I would have to call a welcoming quiet. It simply feels good to be inside that space. That Anne and her husband, Crispin, were actively involved in the construction undoubtedly con-tributes to that sense. When I teach courses on home building I like to take the participants onto the unbroken ground of the building site and have them sit quietly and just “feel” the space in its natural state. When the building is complete and they are surrounded by walls and roof, I tell them, it should still feel that good to sit there. The use of straw bale and other natural materials can intensify the feeling of connection to the site instead of arbitrarily cutting it off at the wall. The rediscovery of straw provides the ideal building material for eliciting the subtle possibilities of a project, and gives us yet another way to create buildings that are supportive of the people that use them.