According to one study, the number-one predictor of longevity is the amount of lean muscle mass on your body.

Tall, lean, smiling, and healthy at age sixty-four, exuding an unstoppable vibrancy that would make the Energizer Bunny envious, it is hard to believe that Dr. Andrew McGill began his life prematurely back in 1947. The expectations that he might actually live were so low that he wasn’t named until he was four or five days old. But such is the strong will of one Andy McGill.

However, in 1999, when Andy was turning fifty-two, he had a wake-up call that would challenge his will to survive in a whole new way. It began when professor Andy McGill attended a seminar I gave at the University of Michigan about ADHD and our work with brain SPECT imaging. At the time, Andy’s high school daughter, Katy, was struggling with ADHD. Curious about SPECT and wanting to make sure Katy had the best current diagnosis and follow-up treatment, Andy flew the whole family to California for a fun day of “having their heads examined” at one of our clinics. Andy heard me say in one of my presentations, “If your child has ADHD, look at the parents. More than likely he or she got it from one of you.”

At that moment, Andy had looked at his wife, Kathe, suspiciously, thinking, “Well, it’s obvious. Katy gets it from her mom.” At the very same moment, Andy’s wife was eyeing him, thinking, “Aha! My husband is the culprit!”

Originally, Andy and his wife’s motivation for getting their brains scanned, alongside Katy, was to help their daughter feel less alone and more comfortable with the process. As it turned out, Katy, who had taken the summer off medication to prepare for the scan, had made such marked improvement that she was able to get off medication completely a few years later. However, Dr. McGill’s scan told a different tale, and an alarming one.

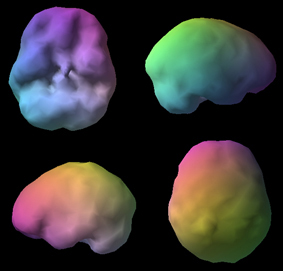

When I first saw Andy’s scan I wondered what I would tell him. It is not easy to tell a kind, educated man who had traveled more than halfway across the country to see you that his brain was damaged and looked much older than he was. His scan looked terrible. There was overall decreased activity in a Swiss cheese toxic-looking pattern. I had seen this pattern hundreds of times. It could be attributed to any number of causes: alcohol; drugs; environmental toxins, such as mold or organic solvents; infections; a lack of oxygen; or a significant medical problem like severe anemia or low thyroid.

When I asked Andy if he drank alcohol, he described what he felt was a pretty normal social drinking routine: a couple of drinks to wind down from a busy day of teaching business classes to college students, then a glass of wine with dinner, and finally, a nightcap before retiring for the evening. Since most “social drinkers” tend to fudge on the number of drinks they actually have, or the size of those drinks, I suspected that four drinks per day was probably the minimum daily drinking quota.

“How long have you been drinking?” I asked.

“Well, as a young man I was newspaper business editor for the Miami Herald and the Detroit News, so I was in a culture where smoking and drinking went hand in hand with the job. I quit smoking back in the seventies. But I’ve put in about forty years of good drinking, all together.”

|

Normal Brain SPECT Scan

Full, even, symmetrical activity |

Andy’s Brain SPECT Scan 1999

Overall decreased activity |

I cut to the chase and told him, firmly and clearly, the realities of his future if he continued to drink, such as early dementia, disease, death, and basically losing his good mind. He was also quite overweight and needed to revamp his diet and start exercising. But the first order of business was that he had to stop poisoning his brain on a daily basis with alcohol. Also, much to his chagrin, I had to tell him the news that Katy’s ADHD most likely came from her father’s side of the brain tree.

Andy thanked me and flew back to Ann Arbor with his family. I had no idea whether or not he’d take my advice to heart (or should I say “to brain”?).

Then, about a year and a half later, our office received a call from Dr. McGill, who wanted to fly out to the clinic again, this time alone (he didn’t even mention this trip to his wife), to recheck his brain. When I saw his scan, I shook my head sadly. His scan was even worse than the previous year.

This time, for whatever reason, Andy somberly assimilated the truth on a deep and profound level.

Andy will never forget New Year’s Eve of the new millennium, ushering in 2001. He was drinking a glass of wine with some buddies at a party. Glasses in hand, they all began talking about how they wanted to stop drinking. Andy said, “I’m going to do it. When I finish this glass of wine, I’ll never drink again. This is my last one.” Amazingly, the McGill “will” kicked in. He never took another drink. (His friends all began drinking again within a few months.) Emotionally ready and intellectually armed after seeing his SPECT scan and hearing my concern, Andy made that solemn commitment, and he knew he would keep this promise to himself. He wanted a new brain for the new decade.

In addition to giving up alcohol, Andy also gave up caffeine, knowing from our talks that too much caffeine constricts blood flow to the brain. Once he had these two issues under control, he started feeling better and decided to tackle the extra 100 pounds.

When he first went to see his local doctor, his weight was at 279 pounds. He exercised sporadically. He got his weight down to 208 pounds in 2002, but it jumped up to 289.5 pounds in 2006. At this time, Andy was attending medical school—at age fifty-nine! He was taking classes and seeing patients as part of his clinical program. One day, he found himself lecturing a diabetic patient about the importance of nutrition, losing weight, and exercise. On the way home he thought to himself, “Andy, what a hypocrite you are! When are you going to stop playing around with your own health?”

Andy hit a wall on November 1, 2006, and not unlike what happened to him the day he stopped drinking, he made a deep, committed vow to himself never to miss a day of exercising. He’s kept that promise for over five years now without missing a single day. Ever. Through sickness, through hard days (“through rain, through hail, through black of night”) the ol’ McGill will keeps on ticking. Once Andy fell on the ice and he was in pain, but having been through medical training, he knew he’d not broken or sprained anything. He was just bruised and sore. So to the treadmill he went.

“I actually find that when I’m not feeling well, which is rare, if I’ll just get on the treadmill for a while, I will almost always feel better afterward.”

“What I’ve learned about myself, based on my history, is that once I break a streak, it’s easier to break it again and I might not stick with the program so seriously or get back with a program again,” Andy explained. “What happens when you allow yourself to take breaks or start giving yourself excuses for days off is that you set up a cognitive precedent.” A man of his word, even to himself, Andrew’s secret of quitting a bad habit and starting (and sticking with) a new one is simple: Just do it. And don’t stop doing it. Don’t break the streak.

“The secret to exercise is to make it happen first thing in the morning, no excuses,” Andy says. “The day will get away from you and you’ll rationalize not exercising all day long if you don’t do it as soon as you get up.”

Andy has also incorporated one of the most positive outlooks on exercise I’ve ever observed. “I’ll tell you what I love about exercising in the mornings,” he says with a wide grin. “I know that no matter what else happens in my day, I can guarantee a part of my day will be great. When I exercise, I feel good. Even if there are troubles or frustrations as the day wears on, I’ve ensured I have had at least one fabulous hour by keeping exercise as a regular, top priority.” In truth, because we know that exercise elevates mood and keeps the energy up throughout the day, Andy is also ensuring that his mood level stays as high as possible all day long, come what may.

Now curious to see if all the changes he’d made over the years had affected his brain, Andy called the clinic for another appointment in late 2010. To tell you the truth, and as I would tell Andy later, I was dreading this, worried that his scan might be bad or have even gotten worse. I didn’t know at this point about the scope of the lifestyle changes he’d been implementing, and of course, he was now almost a decade older since that first awful scan was taken.

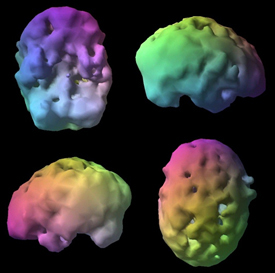

|

Andy’s Brain SPECT Scan 1999

Overall decreased activity |

Andy’s Brain SPECT Scan 2010

Dramatic overall improvement |

What I saw on Andy’s new scan simply made my entire week. As we age, typically our brain looks older, less active. This guy’s brain had aged backward! He was now the proud owner of a much younger, healthier brain than he had ten years before. I was elated to show Andy the scans and share the good news, the happy result of many years of omitting bad habits and steadily applying new ones.

When I asked Andy about his inspiration, he talked about his wife, Kathe, who had been doing her own swimming exercise routine—three times a week—for more than twenty years after being diagnosed with fibromyalgia, and had gotten back to a point of operating at 95 percent of her former mobility. She swims three days a week, in a short wetsuit after pouring hot water inside to warm her muscles, then doing a physical therapy routine of two dozen water exercises. Kathe has found that it is important to keep the muscles of fibromyalgia patients warmed up, and this way she enjoys the benefits of water exercise while keeping her muscles warm.

Today, Andy’s energy level is great and stays steady all day. He doesn’t feel run down or tired like so many his age. He also looks great and feels as intellectually engaged as when he was young, but now he has a wiser, more mature mind. He loves jazz and cooking, along with writing, some adjunct professorial duties, and some pro bono community service activities. He actually feels much more comfortable with students and people younger than himself than he does at the university retiree events. He feels decades younger than his biological age. His daughter, Katy, who once struggled in school, grew up to be a kindergarten teacher in San Diego and has a six-year-old, who happily runs his grandfather around Disneyland and Sea World when he visits. Andy McGill never takes these moments for granted, knowing full well that if he had not made vows to change his health habits ten years ago, he might not be here to see his grandson.

I recently received this encouraging and heartwarming e-mail from Andy, saying, “Along with the 2000 brain scan, it was your matter-of-fact warning, Dr. Amen, telling me that I would be in really sad shape by the time I reached sixty, unless I got serious about repairing the damage and got my brain healthy again. It scared me into action. That is when I became intellectually convinced. While it took me a few more months to become totally emotionally ready and quit drinking, you really saved my life and are responsible for me being as healthy as I am today. Never underestimate that. I may do the exercise. But you were the stimulant.”

Needless to say, letters like this and lives changed for the better, like Andy McGill’s, are why I love what I do.

Not only did Andy get a new, younger brain, he also got a new, younger body. When Andy began exercising, he was so out of shape and weighed so much that even walking at a very slow pace was tough. Today Andy is at an extreme level of fitness. For his morning routine now he runs on the treadmill for an hour, beginning at 3 mph at a 6 percent grade for the first 7.5 minutes, increasing gradually to 4.5 mph and 9 percent level. This routine gets his heart rate up to 125 beats per minute (bpm) from a resting rate of about 50 bpm. On Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays he does forty-five minutes of treadmill and then uses free weights for ten to fifteen minutes.

Andy reports, “I have now achieved a very, very high cardiac fitness level: the 99th percentile for men in my age group, comparatively—also at the 99th percentile for the age-fifty men’s group, the 99th percentile for the age forty men’s group. My regular doctor had to go down to the age thirty men’s group to find a comparative level for me: There I am only in the 75th percentile!”

In addition, on Andy’s last major fitness test, his VO2 (volume of oxygen taken in during exercise) was 63 ml/kg/min (milligrams per kilogram per minute). “Normally, your VO2 is expected to go down when you age,” wrote Andy. “Mine went from 49, when I began my exercise streak in 2006, to 63. I’m told that is considered an extraordinary fitness achievement for my age. Achievements like this also help keep me motivated.”

There are four major lessons in Andy’s story.

1. Being able to see your own brain often creates brain envy and motivates people to start taking better care of it.

2. Alcohol is not your friend, especially lots of alcohol. The sooner you lose it or significantly decrease your intake, the better your brain and body will be.

3. Regular exercise can make a dramatic difference in how you look and feel.

4. Dedicate yourself to brain healthy habits and keep them going for a long, healthy life.

Andy |

|

Before |

After eleven years, down 100 pounds, with a better brain and cardiovascular system! |

I used to exercise for my butt. Now I exercise for my brain.

—DAVID SMITH, M.D., FOUNDER OF THE HAIGHT-ASHBURY FREE CLINICS AND MY COAUTHOR OF UNCHAIN YOUR BRAIN

This is one of my favorite quotes. David is a pioneer in the addiction treatment field, and together we wrote a terrific book, Unchain Your Brain: 10 Steps to Breaking the Addictions That Steal Your Life, on using the latest brain science to help people with addiction issues. As David learned more and more about creating a brain healthy life, his daily exercise routine became more about his brain than his body. Physical exercise is another fountain of youth for the health of your brain. Regular exercise will help you look younger, be trimmer, feel smarter, and boost your mood all at the same time.

Certainly, it is no secret that our society has shifted to a sedentary lifestyle where most of us spend our days sitting—working on computers, watching TV, and driving. The problem is that a lack of physical activity robs the brain of optimal function and is linked to obesity, higher rates of depression, a greater risk for cognitive impairment …and worse.

Physical inactivity is the fourth most common preventable cause of death, behind smoking, hypertension, and obesity.

New research seems to be popping up every day proving that exercise will not only increase how long you live but also the quality of life in those years. Here’s a sample of some of the findings.

A recent study shows that after age sixty-five, one strong predictor of longevity is walking speed. Those who can still hoof it after age seventy-five have an even better chance of living even longer. An eighty-year-old man who clocks 1 mph has a 10 percent probability of reaching age ninety, while a woman of the same age walking at that pace has a 23 percent chance. Now let’s assume this pair is hoofing it a little faster at a speed of 3.5 mph. Now the eighty-year-old man has an 84 percent probability of reaching age ninety, while a woman would have an 86 percent chance.

If you are like me, you’d like to keep every iota of brain tissue you possibly can as you get older. Researchers found that exercise, particularly aerobic exercise, reduces brain tissue loss in aging adults.

Gentle exercise, like yoga or tai chi, increases balance, which decreases falls, which decreases injury and complications leading to death.

Exercising thirty minutes a day, five times a week, can make you look many years younger than your biological age. Researchers from the University of St. Andrews in Scotland found that aging in the form of loose skin on the neck and jowls are the most pronounced effect of not exercising. The forehead and eye area also tend to fatten more in inactive people.

University of Michigan researchers published a study showing that after an average of eighteen to twenty weeks of progressive resistance training, an adult can add 2.42 pounds of lean muscle to their body mass and increase their overall strength 25–30 percent. This is significant because without proactive training, aging adults tend to lose muscle mass and strength. The study recommended that people over age fifty begin by using their own body weight to do squats, modified push-ups, lying hip bridges, or standing up out of a chair. (Also, tai chi, Pilates, and yoga employ many resistance exercises using your own body weight as well.) Then you can add weights in a progressive training program designed specifically for your age and fitness, preferably starting with a personal trainer who can teach you good exercise form with weights, how many reps to do, and when it is time to up your weights.

According to research done at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, individuals with weaker muscles appear to have a higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease and declines in cognitive function over time. Those at the 90th percentile of muscle strength had about a 61 percent reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease compared with those in the 10th percentile. Overall, the data showed that greater muscle strength is associated with a decreased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. It also suggests that a common but yet-to-be-determined factor may underlie loss of muscle strength and cognition in aging.

Exercise improves telomere maintenance by increasing the activity of the enzyme telomerase that builds and repairs telomeres. Telomeres are the part of your chromosomes that control aging. They represent your biological clock. When you are young your telomeres are longer, and they progressively shorten with age. But the rate at which that shortening occurs is directly influenced by lifestyle choices. So at any age, healthier individuals have longer telomeres than their unhealthy counterparts.

There are so many other benefits to regular exercise. Here are a few more of them.

Handle stress better. Working out helps you manage stress by immediately lowering stress hormones, and it makes you more resistant to stress over time. Raising your heart rate through exercise also makes you a better stress handler because it raises beta-endorphins, the brain’s own natural morphine. Increasing your ability to manage stress can keep you from polishing off a whole bag of chips when you are under a lot of pressure.

Eat healthier foods. A 2008 study found that being physically active makes you more inclined to choose foods that are good for you, seek out more social support, and manage stress more effectively. Obviously, choosing brain healthy foods over junk food provides the foundation for lasting health. Creating a solid support network to encourage your new brain healthy habits can help you stay on track.

Get more restful sleep. Engaging in exercise on a routine basis normalizes melatonin production in the brain and improves sleeping habits. Getting better sleep improves brain function, helps you make better decisions about the foods you eat, and enhances your mood. Chronic lack of sleep nearly doubles your risk for obesity and is linked to depression and a sluggish brain.

Increase circulation. Physical activity improves your heart’s ability to pump blood throughout your body, which increases blood flow to your brain. Better blood flow equals better overall brain function.

Grow more new brain cells. Exercise increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF is like an antiaging wonder drug that is involved with the growth of new brain cells. Think of BDNF as a sort of Miracle-Gro for your brain.

BDNF promotes learning and memory and makes your brain stronger. Specifically, exercise generates new brain cells in the temporal lobes (involved in memory) and the prefrontal cortex, or PFC (involved in planning and judgment). Having a strong PFC and temporal lobes is critical for successful weight loss.

A better memory helps you remember to do the important things that will help you stay healthy—for example, making an appointment with your physician to check your important health numbers, shopping for the foods that are the best for your brain, and taking the daily supplements that will benefit your brain type. Planning and judgment are vital because you need to plan meals and snacks in advance, and you need to make the best decisions throughout the day to stay on track.

The increased production of BDNF you get from exercise is only temporary. The new brain cells survive for about four weeks, then die off, unless they are stimulated with mental exercise or social interaction. This means you have to exercise on a regular basis in order to benefit from a continual supply of new brain cells. It also explains why people who work out at the gym and then go to the library are smarter than people who only work out at the gym.

Enhance brainpower. No matter how old you are, exercise increases your memory, your ability to think clearly, and your ability to plan. Decades of research have found that physical activity leads to better grades and higher test scores among students at all levels. It also boosts memory in young adults and improves frontal lobe function in older adults.

Getting your body moving also protects the short-term memory structures in the temporal lobes (hippocampus) from high-stress conditions. Stress causes the adrenal glands to produce excessive amounts of the hormone cortisol, which has been found to kill cells in the hippocampus and impair memory. In fact, people with Alzheimer’s disease have higher cortisol levels than normal aging people.

Ward off memory loss and dementia. Exercise helps prevent, delay, and reduce the cognitive impairment that comes with aging, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease. In 2010 alone, more than a dozen studies reported that physical exercise results in a reduction in cognitive dysfunction in older people. One of them came from a group of Canadian researchers who looked at physical activity over the course of the lifetime of 9,344 women. Specifically, they looked at the women’s activity levels as teenagers, at age thirty, at age fifty, and in late life. Physical activity as a teenager was associated with the lowest incidence of cognitive impairment later in life, but physical activity at any age correlated to reduced risk. This study tells me that it is never too late to start an exercise program.

Protect against brain injuries. Exercise strengthens the brain and enhances its ability to fight back against the damaging effects of brain injuries. This is so critical because brain injuries—even mild ones—can take the PFC offline, which reduces self-control, weakens your ability to say no to cravings, and increases the need for immediate gratification, as in “I must have that bacon cheeseburger right this minute!”

You don’t have to lose consciousness to suffer from brain trauma. Even mild head injuries that do not typically show up on the structural brain imaging tests, such as MRIs or CT scans, can seriously impact your life and increase your risk for unhealthy behaviors. That is because trauma can affect not only the brain’s hardware, or physical health, but also its software, or how it functions. Head injuries can disrupt and alter neurochemical functioning, resulting in emotional and behavioral problems, including an increased risk for eating problems and substance abuse.

Each year, two million new brain injuries are reported, and millions more go unreported. Brain trauma is especially common among people with addictions of all kinds, including food addiction. At Sierra Tucson, a world-renowned treatment center for addictions and behavioral disorders, our brain imaging technology has been used since 2009. One of the most surprising things the brain scans have shown, according to Robert Johnson, M.D., the facility’s medical director, is a much higher than expected incidence of traumatic brain injury among their patients.

Get moving to get happier. Have you ever heard the term runner’s high? Is it really possible to feel that good, just from exercise? You bet it is. Exercise can activate the same pathways in the brain as morphine and increases the release of endorphins, natural feel-good neurotransmitters. That makes exercise the closest thing to a happiness pill you will ever find.

Boost your mood. Physical exercise stimulates neurotransmitter activity, specifically norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin, which elevates mood.

Fight depression. In some people, exercise can be as effective as prescription medicine in treating depression. One of the reasons why exercise can be so useful is because BDNF not only grows new brain cells, but it is also instrumental in putting the brakes on depression.

The antidepressant benefits of exercise have been documented in medical literature. One study compared the benefits of exercise with those of the prescription antidepressant drug Zoloft. After twelve weeks, exercise proved equally effective as Zoloft in curbing depression. After ten months, exercise surpassed the effects of the drug. Minimizing symptoms of depression isn’t the only way physical exercise outshined Zoloft.

Like all prescription medications for depression, Zoloft is associated with negative side effects, such as sexual dysfunction and lack of libido. Furthermore, taking Zoloft may ruin your ability to qualify for health insurance. Finally, popping a prescription pill doesn’t help you learn any new skills. On the contrary, exercise improves your fitness, your shape, and your health, which also boosts self-esteem. It doesn’t affect your insurability, and it allows you to gain new skills. If anyone in your family has feelings of depression, exercise can help.

I teach a course for people who suffer from depression, and one of the main things we cover is the importance of exercise in warding off this condition. I encourage all of these patients to start exercising and especially to engage in aerobic activity that gets the heart pumping. The results are truly amazing. Over time, many of these patients who have been taking antidepressant medication for years feel so much better that they are able to wean off the medicine.

Ease anxiety. Although the research on the effects of exercise on anxiety isn’t quite as voluminous as the evidence on exercise and depression, it shows that physical activity of just about any kind and at any intensity level can soothe anxiety. In particular, high-intensity activity has been shown to reduce the incidence of panic attacks.

Boost your sexuality. Exercise helps to boost testosterone levels and makes you feel sexier. In addition, you look better, which also makes you feel and act more attractive. Even a few pounds or inches lost can make a big difference in how sexy we feel.

Aerobic exercise, coordination activities, and resistance training have all been found to benefit the brain.

Get the most out of your aerobic exercise with burst training. If you want a higher-calorie burn, a faster-fat burn, a greater mood enhancer, and a better brain booster, try burst training. Also known as interval training, burst training involves sixty-second bursts at go-for-broke intensity followed by a few minutes of lower-intensity exertion. This is the type of workout I do, and it works. Scientific evidence says so. A 2006 study from researchers at the University of Guelph in Canada found that doing high-intensity burst training burns fat faster than continuous moderately intensive activities.

If you want to burn calories with bursts, do intense exercise, such as fast walking (walking as if you were late for an appointment), for thirty minutes at least four to five times a week. In addition, in each of these sessions, you are to do four one-minute bursts of intense exercise. These short bursts are essential to get the most out of your training. Short-burst training helps raise endorphins, lift your mood, and make you feel more energized. It also burns more calories and fat than continuous moderate exercise. Here is a sample of a heart-pumping thirty-minute workout with bursts:

| 3 minutes | Warm-up |

| 4 minutes | Fast walking (walk like you are late) |

| 1 minute | Burst (run or walk as fast as you can) |

| 4 minutes | Fast walking |

| 1 minute | Burst |

| 4 minutes | Fast walking |

| 1 minute | Burst |

| 4 minutes | Fast walking |

| 1 minute | Burst |

| 4 minutes | Fast walking |

| 3 minutes | Cool down |

If you can’t devote an entire thirty minutes to an aerobic burst routine, don’t throw in the towel. Research from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston shows that just ten minutes of vigorous exercise can spark metabolic changes that promote fat burning, calorie burning, and better blood sugar control for at least an hour. For the 2010 trial, researchers looked at exercise-induced metabolic changes in people of varying fitness levels: people who became short of breath during exercise, healthy middle-aged individuals, and marathon runners.

All three groups benefited from ten minutes on a treadmill, but the fittest individuals got the biggest metabolic boost. This indicates that as you increase your fitness, your body will become more effective at burning fat and calories with exercise.

Boost your brain with coordination activities. Doing coordination activities—like dancing, tennis, or table tennis (the world’s best brain sport)—that incorporate aerobic activity and coordination moves are the best brain boosters for all types of overeaters. The aerobic activity spawns new brain cells while the coordination moves strengthen the connections between those new cells so your brain can recruit them for other purposes, such as thinking, learning, and remembering.

What I really like about aerobic coordination activities is that many of them also work as burst-training sessions. For example, in tennis and table tennis, you give it your all during the point, then you have a brief rest period before the next point begins. It is the same with dancing, where you dance to the song and then take a short break.

In general, I recommend that all of us do some form of aerobic coordination activity at least four to five times a week for at least thirty minutes.

Have you typically avoided coordination activities because you have two left feet? This could be part of the reason why you have a hard time controlling yourself around food. That is because the cerebellum, which is the coordination center of the brain, is linked to the PFC, where judgment and decision-making occur. If you aren’t very coordinated, it may indicate that you are not very good at making good decisions either. Increasing coordination exercises can activate the cerebellum, thereby improving your judgment so you can make better decisions.

Strengthen your brain with strength training. I also recommend adding resistance training to your workouts. Canadian researchers have found that resistance training plays a role in preventing cognitive decline. Plus, it builds muscle, which can rev your metabolism to help you burn more calories throughout the day. Extensive research shows that adding resistance training to a controlled-calorie nutrition program results in greater loss of body fat and more inches lost than diet alone.

Calm and focus your mind with mindful activities. Yoga, tai chi, and other mindful exercises have been found to reduce anxiety and depression and to increase focus. Although they don’t offer the same BDNF-generating benefits as aerobic activity, these types of exercise can still boost your brain so you can improve your self-control and reduce emotional or anxious overeating.

Eddie Deems has taught ballroom dance for seventy of his ninety-two years, which makes him one of the oldest—and most accomplished—hoofers in the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex. Lithe and graceful in his nineties, Eddie dresses in a handsome dark suit complete with ascot, looking every bit the professional dance instructor that he still is. Eddie is a living testimony to one of the world’s best exercises for longevity: dancing!

Imagine going to the doctor, complaining of depression, and instead of giving you a prescription for Zoloft or Prozac, he hands you an Rx slip that says, “Take ten tango lessons and call me in two months.” As far-fetched as that might sound, it could very well be a better answer than medication for many people with low-mood issues.

“We’ve become a nation of armchair dancers, mesmerized by Dancing with the Stars and So You Think You Can Dance,” says Lane Anderson, author of an article in Psychology Today. “But research shows that getting your own groove on is more beneficial in improving social skills, lifting your spirits, even reversing depression.

“In a recent study at the University of Derby,” Anderson wrote, “depressed patients given salsa-dancing lessons improved their moods significantly by the end of the nine-week, hip-swiveling therapy.” Researchers found that the combination of the endorphin boost from exercise, along with the social interaction and forced concentration, lifted moods. I think it is safe to assume that the emotional boost of music, which calms and energizes the brain, also helped, along with the pride learning a new skill.

In a study from Germany, twenty-two tango dancers had lower levels of stress hormones and higher levels of testosterone. They also reported feeling sexier and more relaxed. Another study from the University of New England showed that after six weeks of tango lessons, the participants showed significantly lower levels of depression than a control group who took no classes, and had similar results to a third group who took meditation lessons. Dance requires extreme focus or “mindfulness” and when the brain is deeply engaged at this level, negative thought patterns that lead to anxiety and depression are interrupted.

Using the body in physical, rhythmic movement also plays a part in opening people up on several levels. “Depressed patients tend to have a curved back, which brings the head down so it’s facing the ground,” said Donna Newman-Bluestein, a dance therapist with the American Dance Therapy Association. “Dancing lifts the body to an open, optimistic posture.”

So grab your partner and do a little waltz around the kitchen, or go ahead and turn on “Dancing Queen” full volume (nobody’s looking, right?) and get your groove on. What have you got to lose but a bad mood and a few pounds?

In addition to keeping a streak, another aspect that is unique to Andy’s story was his “all in” approach to two life-altering decisions, from which there was no turning back. Not even a slip-up. It reminds me of that famous scene from The Empire Strikes Back in which Yoda tells Luke, “Do or do not. There is no try.”

What enables people to make these strong vows to themselves that they simply don’t break? Where there is no more “try,” there is only “do.”

Dr. Joe Dispenza, author of the book Evolve the Brain: The Science of Changing Your Mind, wrote: “I hope you’ve had this experience in your life where your intention, your focus and your will have all come into alignment.” Dr. Dispenza has become a friend and refers many people to our clinics. I think he is on to something here. Ponder for a moment about vows you’ve made to yourself in the past, and think about what occurred in the times that you kept a vow and never broke from it. For some of you, perhaps, there was a moment where you said to yourself, “I will not be abused anymore” and broke free from an abuser, never to return. Or maybe it was the moment you chose your career path, knowing all the years of schooling and training ahead of you, knowing too that this was the course for you, so you signed up, went all in, and finished your degree. These were moments when your “intention, focus and will” collided to facilitate major change. I believe that intention, focus, and will stem from your PFC (the brain’s supervisor) and your limbic system (emotional brain), working in tandem. Together they help you make the kind of deep, intrinsic, lasting vow to yourself to make radically better choices for your new, improved brain.

In a recent conversation with Dr. Joe Dispenza he shared more about the why and how of getting to an “all in” decision for your well-being, which could positively change the course of your life.

To begin the change process, Dr. Dispenza teaches others to become “metacognitive.” This means that we step back from our thought patterns and observe them. We “think about our thinking patterns.”

“ ‘What if?’ questions, when we start to speculate about new ways of thinking and being, open up a world of possibilities,” he says. The PFC loves these kinds of questions, finds them stimulating. “Why not wake up every morning and begin the day by reminding yourself how you want to be and feel?” he asks. “And also remind yourself of who you don’t want to be each day.”

Dr. Dispenza points out that how you think creates how you feel (emotions). How you feel (your emotional state) creates a mood that, if left unchecked, eventually creates a temperament and, ultimately, your personality. Your personality, no doubt, ultimately affects your sense of reality. So much starts with a single thought. As the ancient proverb goes, “As a man thinks in his heart, so is he.” But how do we really make up our minds to change? Dr. Dispenza says it has to do with creating a firm intention (with our PFC) that is strong enough to break old habits.

One way of creating new habits is to mentally practice. In one experiment, Dr. Dispenza points out that non-piano-playing people were taught to practice a series of finger movements on the piano for two hours a day, for five days. Another group of non–piano players was asked to mentally “practice” playing the piano (without moving their fingers) for the same amount of time. Brain scans showed that both groups showed the same pattern of new learning had taken place in the brain. Mental rehearsal, alone, changed the brain in the same way that actual practicing with the body did. Spending some time visualizing exactly how you’ll spend your day in order to be healthier and live longer is a valuable mental tool in prepping you for that “all in” decision to change once and for all.

Dr. Dispenza’s work emphasizes the brain science truth that “neurons that fire together, wire together.” The more that you feed your brain new experiences and new learning, the more those neurons fire; and the more you repeat similar experiences and layer similar knowledge, the more your neurons fire and wire together. Under heavy-duty microscopes, the neurons look very much like threads coming together to create a fishing net. In fact, this is what is called a neural net. Another way, then, to make a “once-and-for-all decision” is to feed your brain new experiences and new learning until your neurons “fire and wire together” to become new neuron nets, or new automatic thoughts and actions. For example, the more you read and study books like this one on brain health, the more you create connections of information that link together and begin to change your brain. The more you risk new experiences over time—like eating more fruits and vegetables every day or walking for thirty minutes a day—the more this becomes a good habit.

Another way to help your brain change is to read and study those whose lives you’d like to emulate. Dr. Dispenza enjoyed Nelson Mandela’s biography because it taught him how a noble man can suffer unjustly, for years, in a prison and then forgive and go on to great things with his life. The biography of the Wright Brothers is of great encouragement for someone risking a dream that seems unrealistic to many. Abraham Lincoln is a role model of honor, integrity, faith, and humor in a time of great crisis. I am sharing stories of real people in this book who have changed their brain, changed their life and their biological age, to help inspire you to believe that you too can change.

“The problem with the way most people make decisions to change is that they’ll tell themselves, while lying on the couch with the remote, eating junk food and drinking beer, ‘I’m going to get my act together and change tomorrow,’ ” explains Dr. Dispenza. “But the body is saying to the mind, ‘Oh, relax. He doesn’t really mean it. He always says this over and over but he never changes. Go ahead and have another potato chip and a swig of beer.’

But when you really truly make up your mind and are in a state of firm intention—that is, you absolutely know that you are going to follow through on a new way of thinking or acting, you can almost feel the hair on the back of your neck stand up. You are saying to yourself, with deep conviction, ‘I don’t care what anyone else says or does. I don’t care what happens or what challenges I face. I don’t care how hard it is. I am going to do this. I am going to change.’ When you are at this point of serious, firm attention, your body sits up and pays attention. It knows the brain means business. And the body will now follow the direction of a firmly convinced prefrontal cortex.”

Dr. Cyrus Raji, M.D., Ph.D., is a bright, articulate, kindhearted doctor and researcher at the University of Pittsburgh’s Department of Radiology, who oversaw and released some fascinating studies on the correlation between Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and physical activity. He has also become a good friend, as we both share a keen interest in the brain and longevity.

Dr. Raji comes to an interest in helping the brain stay healthier longer from personal experience. Cyrus’s grandmother was a teacher, a brilliant woman who spoke five languages. But she was a smoker, suffered from a couple of strokes, and eventually succumbed to dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. In her waning years of life her brain was reduced to that of a lost and confused child. Watching this bright light in his life grow dim, Cyrus has dedicated much of his career to doing what he can to stem the ugly tide of dementia and Alzheimer’s in the world. As I mentioned in chapter 1, over five million Americans currently suffer from this disease, and because it doesn’t just affect those who have Alzheimer’s, but those who love them, the ripple effect of pain is tremendous.

Dr. Raji has been involved in brain imaging and Alzheimer’s research for seven years, but for the last five years he’s concentrated his research on how lifestyle factors can affect our brains positively or negatively. Using a special type of brain scan, researchers can measure the overall amount of volume in the brain as well as the volume in individual parts of the brain. The larger the volume in a brain, the healthier it is. When a brain is unhealthy or gets old, it will shrink, and the neurons will get smaller as well. But when a person has Alzheimer’s disease, the neurons don’t just shrink—they actually begin to die in the parts of the brain that are responsible for memory, organization, and personality.

Dr. Raji has been involved with a study that began in the 1980s, following 450 individuals over a period of twenty years, specifically to observe how lifestyle factors affected their brains as they aged. Some amount of brain shrinkage is normal in aging. Scientists call this process atrophy; the brain shrinks much the way a muscle will shrink when you don’t use it. As the brain atrophies, senior moments happen with increased frequency.

However, in Alzheimer’s disease, because the neurons are dying, there are actually fewer of them in the parts of the brain that help a person organize their day, remember things and people and places, and make up a large part of their personality.

One of the first studies that Dr. Raji worked on looked at how obesity affected brain volume in a group of normal people (individuals with no indication of brain deterioration issues). I mentioned this study in chapter 1, but it is worth repeating. He measured obesity using the body mass index (BMI), which is your weight divided by your height squared. A normal BMI is between 18.5 and 24.9; overweight is 25 to 29.5 (one hundred million Americans are in this category), and over 30 is considered obese (seventy-two million people in our country fall into this category). What Dr. Raji and his research team found was that the higher the obesity, the lower the brain volume and the higher the risk for Alzheimer’s. Those who were overweight had some shrinkage. Those who were not overweight had no preshrinkage. This is the study upon which I base what I call the dinosaur syndrome in my PBS specials: the bigger the body, the smaller the brain. Not good. Dr. Raji’s group repeated the study using seven hundred individuals with early stage Alzheimer’s and found that obesity makes things worse. (They didn’t use people in late stage Alzheimer’s because people at this stage are thin since they are forgetting to feed themselves, and at this point, losing weight is not going to help their brain. It’s too late.)

When Dr. Raji published this study, it received a lot of media attention. It was a “downer of a finding,” Dr. Raji said in a recent conversation. This was the stimulus to find something positive that might help alter a bad brain trend. So he began to look at how lifestyle factors, particularly physical activity, might help the brain. He and his team looked at the most basic kind of simply physical activity anyone at any age can do: walking. He knew if they could prove that walking helped the brain, then it would follow that more exercise would do the same or perhaps even more good for brain volume.

“We looked at the effect of walking on 299 cognitively normal subjects,” Cyrus shared. “We found that people who walked a mile a day or about twelve city blocks, six times a week, had increased brain volume over time in areas for memory and learning.” Taking it further, he discovered that there would be a 50 percent reduction in the possibility of getting Alzheimer’s over a thirteen-year test period. (Another way to say this is that Alzheimer’s was cut down by a factor of two.)

In November of 2010, Dr. Raji looked at 127 people who had what we call mild cognitive impairment (lots of “senior moments”) and were at a high risk for getting Alzheimer’s or early stage Alzheimer’s. “We looked at the effect walking had on their susceptible brains. In this study, we only had people walk about five miles a week, or three-quarters of a mile per day. The good news was that walking preserved their brain volume. It didn’t increase their brain volume but it helped them to preserve what they had, without further brain shrinkage.” This benefit even extended to those in the obese category. For anyone of any weight, walking stemmed the tide of brain atrophy.

Dr. Raji is often asked about other types of exercise for people who don’t like walking. His reply is always, “Do what you like to do because you’re more likely to participate in it more often. Being physically active improves blood flow to the brain. It delivers oxygen and other nutrients to your neurons.”

When software developer Brad Isaac asked Jerry Seinfeld, who in those days was still a touring comic, what his secret was, Seinfeld asked Isaac to pick up one of those wall calendars that had the entire year on a single page. To Seinfeld, becoming a better comedian meant writing every day, so for each day Jerry worked on his writing he would put a big red X in the box for that day. Pretty soon, there’d be a chain of red Xs and not breaking the chain became its own motivation. Some people might think Andy McGill’s dedication extreme, but it is often the hallmark of a successful person. Keep a good streak going.

There are moments when, caught up in the mental resistance that keeps us from getting started, we forget just how enjoyable the act of doing really is. When you’ve finally started and you’re engaged in the work, you think, “Hey, I kind of like this.” What I love about the Seinfeld calendar idea is that it lets you divert your stubbornness away from the “I don’t wannas” and redirect to not wanting to mess up a good winning streak.

When I was in Sacramento recently for public television, the station manager used the same technique for exercise. He got on his treadmill for thirty minutes a day and marked an X on the calendar. So satisfying was that series of Xs that he felt he had to keep his streak going. Then it became a habit. I urge you to try the “wall calendar and X system” as you begin your habit of daily exercise. This simple visual engages the brain in a way that motivates your body to get with the program. The chart appeals to your logical PFC; but the series of Xs, signifying accomplishment, gives your limbic system a little rush of good feelings. Ka-ching! Your brain is buying in!

Bottom line? Find an exercise you like, whether it is walking around the block or hitting the gym or dancing with the stars (in your living room) and make up your mind, in firm intention to just do it. Your body and brain will thank you for decades and decades to come!

1. It is never too late to be the person you always wanted to be. Stopping a bad habit, like drinking too much, and adopting a new one, like exercising every day, is something anyone can do when they have truly made up their mind to change. Consider “doing an Andy McGill”—stop a bad habit today, and replace it with a new one right away.

2. Most “social drinkers” underestimate the amount they drink and the damage it is doing to their brains. Take a look at Andy’s “before SPECT” scan again. If you know you are drinking too much, remember that excess alcohol is toxic to your brain. The “potholes” in an alcohol-soaked brain scan represent areas where your brain is not getting enough blood to function well. Determine to make your brain a “toxin-free zone” and get the blood pumping through it again!

3. Adopt Andy’s attitude that daily exercise will ensure that one part of your day will be great! No matter what else happens, you can enjoy and feel energized in the special time you set aside to love yourself by investing in your health. Good mood endorphins are your immediate reward! Good health is the long-term payoff.

4. Start a streak and don’t stop it! Try getting a calendar that you use only to keep track of your exercise. Make an X on it every day you exercise and set a goal to have five to seven Xs on your calendar every week for the month. Reward yourself when you meet that goal! Then do it again, and again and again . . .

5. Your brain knows whether or not you mean business when you make a resolution. Set aside some time to let your brain and body know that your commitment to change is no joke by saying to yourself, with deep conviction, “I don’t care what anyone else says or does. I don’t care what happens or what challenges I face. I don’t care how hard it is. I am going to do this. I am going to change.” Write it down and reread your promise to yourself often.

6. Begin every morning by reminding yourself how you want to be and feel. Help create your own great day by doing this. Also remind yourself of how you don’t want to feel and what steps you’ll need to take to ensure you have a fabulous day—beginning with taking time out of your day for exercise.

7. Expect for it to take some time to push pass the discomfort of adding a new routine, like daily physical activity, into your life. The brain likes the status quo, but it can be trained to change and upgrade itself. Take custody of your brain and body! Push through the unease, until exercise becomes a familiar and routine habit, like brushing your teeth.

8. Instead of reaching for sweets, fatty snacks, or alcohol when you are stressed, do something that will really work to lower anxiety and upset: Work up a sweat! Working out helps you manage stress by immediately lowering stress hormones, and it makes you more resistant to stress over time.

9. If you are suffering from mild to moderate depression or even a temporary low mood, remember that exercise can be as effective as an antidepressant without the negative side effects. In fact, the side effects are positive: You’ll look better, have a better body, and increase your libido. Even if you take antidepressants for severe depression, exercise can boost the effects.

10. Besides longevity, looking good, and enjoying more energy, remind yourself that exercise is one of the best and proven preventions for dementia, cognitive decline, and Alzheimer’s. If scientists could patent a pill with these kinds of results, they’d be very rich.

11. Everyone is motivated to get healthy for different reasons, but I have found that sharing the research finding that “as your weight goes up, your brain size goes down” is a powerful motivator for many people to get moving and get their weight under control.

12. Most people who do not exercise first thing in the morning, won’t get it done. The day and its to-do lists invade us and provide excuses to miss our workout. Do your physical activity routine in the morning as part of your regular morning routine, and the habit will be easier to maintain.

13. Walking a mile six days a week is generally an easy and doable activity for most people and proven to help protect the brain. However, the best exercise for you is the one you will do! If swimming is your thing, by all means do that and enjoy it! If you like tennis, incorporate that into your weekly routine. Do whatever exercise floats your boat. The main thing is to simply do it, and do it almost every day, for consistency.

14. Consider dancing if you enjoy the music and the beat. It can keep you young at heart, can lift depression, keep you socially connected, and enhance your brain and your body.

15. Ever notice that you sleep better on days when you get physically active? And that you may have trouble getting to sleep and staying asleep when you’ve “couch potatoed” the day away? Engaging in exercise on a routine basis normalizes melatonin production in the brain and helps give you a good night’s worth of z’s. Good sleep enhances your mood and decision making and also lowers your risk for obesity and depression.

16. Want to look younger? Those who do not exercise look older because they have more loose skin on their face and neck. Those who exercise tend to look years younger than those who do not.

17. Lifting weights or using your own weight as resistance can increase your muscle strength and stamina, and tighten up the muscles beneath your skin, giving you a whole body “lift.” While watching TV, do some sit-ups and push-ups or leg lifts or squats. Keep a pair of handheld weights near the couch and pump some iron while you are watching the tube.

18. Get the lead out! Walking speed is a predictor of longevity, so try to put a little pep in your step. I tell people to walk as if they are late for a meeting.

19. Stretching and bending exercises such as yoga, Pilates, and tai chi help strengthen your core, support flexibility, reduce stress, and aid in balance, which can reduce your risk of falls.

20. To really burn calories, try burst training, which involves going all out for a few minutes followed by more moderate exercise. Run as fast as you can for a minute, and then walk fast for four minutes and repeat until thirty minutes or more is up.