THREE

The First Cleanup of

Love Cemetery

A great people is made not by its blood but by its memory, by how well they transmit wisdom from the elders to the youth…. A people is its memory, its ancestral treasures.

—Robert Pinsky

“That’s why I am here today,” Joyce Schufford told us when we met outside the first of the two gates we had to pass through to get to Love. “To keep those graves clean, like we used to. That’s what I want.” It was July 31, 2003.

We were waiting for my cousin Philip, Doug Gardiner, the assistant scoutmaster, and the scouts they were bringing with them for our first cleanup.

Joyce, dressed in a short-sleeved yellow shirt, with her hair pulled tight off her neck, was ready for the July heat. Her sister, Clauddie Mae Webb, wore her signature tri-cornered straw hat as well as a long-sleeved purple shirt and work pants. Rev. Marion Henderson, well into his eighties, was the oldest member of the descendant community to go in with us. Though he claimed he couldn’t work much, he was dressed in old denim coveralls and looked like he wasn’t going to let age stop him from trying. Two of the scouts from Troop 210, Luke Girlinghouse and Ulysis Bedolla, had ridden out with me. Nuthel was there, of course, along with R.D. Johnson—Doris Vittatoe’s brother—and Willie Mae Brown, a relative of the Johnson family. Altogether six members of the descendant community had come for this first communal cleanup. Three were over seventy, and two were in their late sixties. Nuthel would be eighty the following week. As she had said in March, we needed to get the oldest people—the keepers of the group memory—to come with us to identify graves.

Nuthel looked like she was ready for combat in the army fatigues that her career military son had sent her, but she was smart, for no matter how hot it got—it was already ninety-five degrees and climbing at eight in the morning—it was important to stave off the poison ivy, nagging brambles, and thorny blackberry vines. I wore long sleeves and long pants too. Nuthel had brought a machete, as well as several cases of cold drinks for the scouts, she so appreciated their coming.

A rifle shot went off in the distance, then three more in quick succession. Hunters—but this time I didn’t jump. Mourning doves called down from the trees.

While we waited, I asked everyone to form a circle under the pines so the descendant community and the scouts could meet one another. I asked Nuthel to fill in the scouts on the history of the cemetery, but she insisted that R.D. do the talking.

R.D. was a big man in his early seventies, six-foot-two with a wide girth and grizzled white hair, dressed simply in a white t-shirt and denims. His voice was deep and fairly boomed a greeting into our circle. “I’d like to say good morning to all of you. I am the grandson of Richard Taylor—Poppa, we called him, my mother’s daddy. I was born in 1932, Poppa died around 1940.”

The descendant community stood together, listening solemnly. Luke and Ulysis, the scouts who drove out with me, stood in rapt attention behind Joyce while R.D. told us a little about Love Cemetery.

“Katie Taylor was my mother. All her uncles and aunties were buried back there,” he said, pointing back over his right shoulder with his thumb, “but since they fenced this place in and you had to find somebody to let you in here, we just bypassed this place. Other words, we didn’t think about going back in there, trying to keep it clean. But we always remembered Love Cemetery because all our ancestors were buried back there: Ohio Taylor, Richard Taylor, the Jacksons, the Browns, the Webbs, Nuthel’s people—they’re all back here.

“I’d like to say I am very proud of you, trying to get back in here and line it out where we can keep this cemetery alive. So in loving memories of our foreparents, if they were here, you would get the credit for fixing it where we can go back and check on it. And I’m so proud of these young men coming to try to help us to get it clean because I am seventy-one years old now. I can give a little advice and help here and there, but when we get young men who are willing and able to come back and help us, we the Ancestors of Love Cemetery appreciate everything you all are doing. I think God will bless you and may God ever keep you in his care. Thank you.”

The circle began to break up just as Doug and Philip showed up in their pickups with two more scouts, Tony and Adam Harmon, two hefty brothers, one sixteen, the other seventeen. Doug wore a wide-brimmed white straw cowboy hat and a faded gray t-shirt and jeans. Doug, like my cousin Philip and R.D., stood about six-two. Unlike Philip, Doug wore a neatly trimmed full beard and black wraparound sunglasses. We had another quick round of introductions and then sorted ourselves into the various pickups and drove in.

The scouts fanned out and were quickly swallowed up in a sea of summer green. Soon the sounds of machetes cutting through heavy vines—thwack, thwack— rang through the woods. Since Nuthel, Doris, and I were there four months earlier, the wisteria vines had grown seven or eight feet and even more in places. They were draped over bushes and entwined around trees. The scouts popped up and down in the undergrowth, disappearing as they got down on their hands and knees to look for headstones, standing up again when they’d had no luck and needed to get oriented. Luke was the easiest to spot, with his tall lanky frame topped by a red baseball cap and red-and-white striped t-shirt. It was Luke who first called out, from underneath a mountainous tangle of wisteria and chinaberries, “Hey, I found one!” He read out: “J-A-C-K-S-O-N” from a small, rusted metal marker. This was one of the few temporary funeral home markers that still had a name visible. Others were twisted back on themselves or blank or entirely missing the small, neatly typed card that had been placed under a little rectangle of glass.

“Did you get that, Ms. China?” Luke asked as he spelled the name out again, making sure I had written it down. Everybody was Mrs., Ms., or Mr. to the scouts, from Rev. Henderson on down. We were all their elders. And so we worked through the morning, finding grave after grave, many of them with no name left to read.

The familiar drone of cicadas in the trees filled the air, their chorus rising and falling, throwing me back into a treasured childhood summer day when my mother and grandmother put me on the train to East Texas from Dallas at the old Highland Park station. “All aboard!” the conductor called. “All aboard!” At ten, I couldn’t wait to get to East Texas for another hot July full of the outdoors and always someone to play with; I had at least a dozen cousins who lived near my great-grandmother’s house.

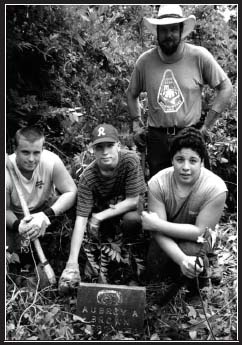

Assistant scoutmaster, Troop 210, Doug Gardiner (standing), with Tony Harman (l), Luke Girlinghouse (m), and Ulysis Bedolla (r)

As I pushed vines aside or pulled them up to cut, I stopped to make a note of stone markers we found. I followed the path Ulysis opened up with his machete and felt deliciously at home.

In a burst of gratitude and pride, I called out to Philip to thank him for his willingness to jump in and for bringing these eager scouts to help. He laughed and spoke in his simple, understated way. “I’m not doing anything special. Mrs. Britton, Mrs. Vittatoe, Mr. Johnson, Mrs. Brown, Ms. Webb, Mrs. Schufford, Rev. Henderson—these people are part of our community. They’re my neighbors. The people buried in here in Love were their relatives, this was their cemetery, this is just what you do when your neighbors ask for help.”

After a good hour of hunting and clearing, Ulysis popped up again. “Hey, I found one, a big one,” he announced, and disappeared from sight again. He’d stooped down to read the letters and whatever date he could find. Moments later he stood up and called out, “Ohio Taylor, died 1918.” He had rediscovered the headstone that Nuthel, Doris, and I had found in March. It was Doris and R.D.’s great-great-grandfather, only now the summer growth had swallowed up the tombstone. We had a big job ahead of us to free it from the vines and bushes.

R.D. made his way through the thicket to Ulysis, calling out, like a surgeon, “Bring me some long-handled clippers!” Philip worked his way over with an ax. I found the clippers R.D. needed in the back of Philip’s truck, and by the time I waded out to them, R.D. was using Philip’s ax to chop down a young chinaberry. Thwack! It was down in two blows.

Philip took his ax back from R.D. and cut down a chinaberry in front of the headstone. Doug, red-faced from the heat, his gray t-shirt dark with perspiration, clipped the vines that had bound the small chinaberry trees together and dragged them off to the side. Once those chinaberries were down, we could see Taylor’s headstone, an age-darkened, streaked granite rectangle with a flat, smooth top.

“Cut those vines right here,” I heard R.D. tell Ulysis as I headed back to the trees. He was guiding Ulysis around Ohio’s headstone. “See what I say,” he said with an edge of frustration in his big, gravelly voice, “they knocked over all these tombstones—Ohio Taylor, Richard Taylor. Ohio’s was tall as I was; now these pieces are laying around here on the ground. Look here at that lamb they knocked off”—another piece we had found in March—“that’s from another Taylor grave.”

“Somebody got in here and cut some of those big pine trees down and knocked these tombstones all over. See the stump here?” he said, pointing to a nearby stump that had emerged from Philip’s clearing. “It got cut down about four or five years ago, you can tell by its condition. Now hand me those long clippers.” Whoever stole those trees, they had done it in the last four or five years, he was sure. That was wrong, he said—those trees belonged to the cemetery.

“When they dragged those big pines out, that’s what tore up this cemetery. These things here,” he said, gesturing at the fluted columns and the plinth on the ground, “they were sitting on top of Ohio’s grave, my great-grandfather. We need to put this back together.”

I went back to where Nuthel and the other women were sitting—except for Clauddie Mae, who was out of sight somewhere on the burial ground, determined to find the headstone marking the grave of her father, Claude Webb, and the row of five Webb family members that lay alongside him. Nuthel had put her machete away and was sitting in the shade on the Hendersons’ tombstone. It was 102°F and still climbing; she wouldn’t be able to take the heat much longer.

We watched as R.D. bent over and picked up one of the fluted columns and carefully placed it where it belonged, on one side of Ohio’s headstone. The metal anchor inside the column had been sheared off by whatever hit it. I had tried to lift one of those columns when Doris and Nuthel and I were here in March, but I couldn’t budge it in the slightest. I could hear R.D. breathing hard. Nonetheless he got the other column as well and carefully laid it on the other side. He knew how to pivot the weight to put those columns in place with the kind of grace that comes only from experience. Then he got Ulysis and Luke to help him with the plinth—the graceful, elegantly engraved triangular stone, incised with ivy and oak leaves, that rested on top of the two columns. Heavier than the columns, it took all three of them—the two scouts and R.D.—to get it securely balanced in place.

R.D. Johnson (l.) and Philip Verhalen (r.)

Ulysis Bedolla Clearing Ohio Taylor’s Grave

From where we sat, Ohio Taylor’s grave marker emerged like a ship on the horizon, low in the water, weighed down with memory. It was balanced precariously, but it stood now as it had stood for over three-quarters of century.

“My, oh my,” Nuthel said, “now look at that.”

After the excitement of seeing Ohio Taylor’s grave put back together, Joyce joined Nuthel, sitting back-to-back on the Henderson headstone. We were dripping and wiped our faces with bandanas or tissues, whatever we had. Willie Mae wore a cool, beltless purple dress with white embroidery, and seemed to have fared the best with the heat. I sat on the ground on my day pack, trying without much success to avoid poison ivy.

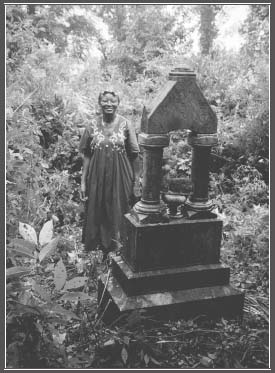

Willie Mae Brown

I needed to tell Nuthel what I had found out about Della Love, the mysterious woman who deeded this cemetery to the Love Colored Burial Association in 1904. Nuthel had given me a copy of the original 1904 deed and told me that Della Love was a white woman, part of the Scott family. The Scotts had been the largest landowners in the eastern part of the county; Scottsville was named after them. Old man W. T. Scott brought in the railroad and ran it due east from Marshall past his cotton gin in Scottsville and over to nearby Caddo Lake, where they could load the bales onto paddle steamers that ran downriver to the Cotton Exchange at New Orleans.

The Scotts were also the biggest slaveholders in the county. My great-grandfather had bought the land from them in 1900 for what became the Verhalen Nursery business. Next to their original plantation in Scottsville was the historic white Scott cemetery, boasting elegant marble statuary and a Gothic-style stone chapel with stained-glass windows. Beyond that cemetery, another mile or so up the road, there was a well-populated black Scott cemetery. There was an endless mixing of blood in slaveholding families, with many African American children fathered by white slave-owners. I was surprised to see it as open and public, if not acknowledged, as it seemed to be in the white and black Scott cemeteries down the road from each other. There was also the black Rock Springs Cemetery just on the other side of the fence from the white Scott cemetery. Some say that Rock Springs began as the burial ground for enslaved people on the Scott plantation. It continues to be used and maintained to this day, like the Scott cemetery.

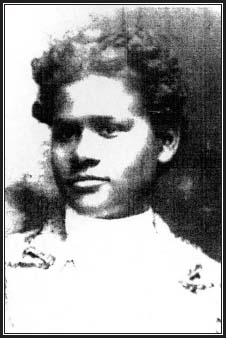

Before this cleanup, I told Nuthel and the others, I’d gone down to the Harrison County Historical Society Library to find out what I could about Love Cemetery. The librarian, Edna Sorber, brought out an unusual homemade book devoted to the Love family, The Love Line.11 The book included a photograph of Della Love that made it clear Della was black, not white. Nuthel’s eyebrows shot up in surprise. So did Joyce’s and Willie Mae’s. All three of them exclaimed “Ohhhhhh…!” at the same time.

Della Love Walker, 1883–1920

According to the Love family history, Della Love’s father, Wilson Love, was half-white. His brother, Nat Love, went west and became the famous black cowboy “Deadwood Dick.” Wilson’s father, Robert Love, was a white plantation owner from Ireland. Wilson’s mother had been Robert’s household slave, and Wilson was apparently one of those rare free black men in 1860s Marshall. Free African American men were not welcome in Texas. They were considered a threat to the institution of slavery, and it was against the law for them to enter Texas. As historian Randolph Campbell writes in An Empire for Slavery: The Peculiar Institution in Texas, there were only about 350 free blacks in the entire state of Texas in the 1860s, just before the Civil War broke out. Wilson Love’s upbringing as a free black man would have made him a lonely anomaly in Harrison County, where virtually all African Americans were enslaved until after the Civil War. Prior to Emancipation, an “owner” had to petition the Texas State Legislature if he or she wanted to free someone they held in slavery, for in the eyes of the state, “Negroes were fit only to be slaves.”

Wilson married an African American woman, had a family, and divorced, then married Della Love’s mother, who was also black. Despite Wilson’s astuteness in buying more than two hundred acres of rural land in the county, either by himself or with business partners, he was declared mentally incompetent in 1882 and a guardian was appointed by the court. He was only fifty years old. Wilson Love died the following year, 1883. Compounding the mystery of Wilson’s mental condition is the fact that the records of the lawsuits that ensued over Wilson’s estate, according to one Love family history, seem to remain missing from the Harrison County Clerk’s office.

Had Della inherited land from her father—is that where this cemetery for the Love Colored Burial Association came from? Had she bought it herself? Della married, had several children, and moved to Oklahoma with her husband. In the self-published history, the text following the photograph of the attractive, alert woman said that Della died on an Indian reservation in Oklahoma, probably after being poisoned, in 1920.

A chorus of sighs greeted this news. The women shook their heads. None of us knew how to respond to these seeming non-sequiturs. Lawsuits. Indian reservation. Death by poison. I explained that I felt that I’d reached a dead end with my research on Della, at least for the moment.

The mood changed when Nuthel said decisively, “We got to clean up Love, now ain’t that the truth? No matter how it came to be here, if this was all cleared, you’d really see something. It’s a beautiful place.” Everyone agreed.

I noticed that R.D. was sitting nearby on a big tree stump, taking a break too, drinking ice water and wiping his face with a kerchief. Most of his white t-shirt was soaked through and sticking to his chest. The scouts were still out clearing and burrowing under the vines looking for more graves. They labored on, unfazed by the sun, unimpeded by age, propelled by the unfamiliar excitement of finding graves. Doug worked with a broadax to cut high vines, while Philip was in the thick of it, chopping down trees whenever he could, the sound of his ax echoing in the woods.

“How you doing, R.D.?” I asked. He allowed that he was enjoying his break but was planning to get up and work a little more before we left. A breeze stirred under the trees shading the stump he sat on. “Now that feels good, mighty good.” He took another big drink of ice water. “Soon as I’m done restin’ up a bit, I need to get over there and tell those young boys to be on the lookout for some things might not come to mind too easy, they bein’ so young and not familiar with our ways.”

He explained that everyone who was working on the cleanup needed to be aware that graves might be marked in all sorts of ways.

“A lot of these folks out here, they didn’t have money for no headstone,” R.D. said, as Nuthel and the others leaned in to listen. “They were all farmers back here. They just used what they had. Plates, crocks, plow points, churns. Just put something on the grave so they know who was buried where.”

“Old lamps,” Nuthel added.

“That’s right,” R.D. said, “and plenty of them, old kerosene lamps.”

I later learned it was an African tradition to put a lamp on a grave, to guide the soul of the deceased and light their way.

“Even a sewing machine, or part of one,” Nuthel said, “if somebody’d been a seamstress.”

“Uh-huh,” R.D. said. “You would be surprised. Could be an old pipe, anything connected to that person.”

Just then, Clauddie Mae returned and told us that she and Joyce had found the grave of their father, Claude Webb, and several more relatives. She was very happy but had to leave early to take Rev. Henderson back to his house. His wife was in the hospital and it was time for him to get changed and go for a visit.

Nuthel, R.D., Willie Mae, and Joyce switched from cataloguing types of grave markers to rattling off more names of people they knew who were buried out here: Taylor, Brown, Sparks, Webb, Jackson, and Henderson. The gentle talk, the shade of the trees, the comfort of ice water to drink, the sound of a woodpecker drilling into a tree nearby all coalesced into a sense of deep peace. Nuthel was right. This was a beautiful place.

I checked my notebook for some other names of people I’d been told we would find here: the Jenkins, Kings, and Johnsons—more of R.D. and Doris’s relations—and the Brooks, Mineweathers, Samuels, and Woodkins.

There had hardly been any air movement, but suddenly a breeze whooshed through the trees. It made me think of the tree that had crashed here months earlier when Doris was with us, when Nuthel explained that it was the Ancestors. I asked R.D. what he believed about them.

“My belief is the Ancestors come back, in a sense, because if you will notice you can come to a place like this and if it gets late in the evenin’, you hear a noise,” he said authoritatively, elongating his words, pausing, pacing himself, as if he were telling us a story around a fire. “Sometimes you will hear a fox howl. Or a treetop fall. That’s a noise they’re making to let you know that they know you’re here. That’s really true.

“They know we’re out here working today,” R.D. continued, “and they are proud of us cleaning this cemetery back up. They know we’re here. They’re smiling on us right now.”

“And they know why we’re here,” said Nuthel.

Now even the scouts were almost done. Philip, still out in the sun in the middle of the cemetery, called out that he was “just about warm” and thought it was time to head back to the house. Philip’s wife, Carolyn, would have hot dogs waiting for us, so we could all have lunch together. It was well after one in the afternoon.

“Do you think we could do a little singing and praying before we leave here today?” I asked R.D., feeling that the end of this first cleanup day needed to be marked.

“I will do anything for the upbuilding of God’s kingdom,” he replied with a big grin.

I called to the others: “Why don’t we all circle up. R.D.’s going to lead us in a prayer and a song.”

The scouts gathered respectfully, taking their hats off, and stood in a rough circle with the rest of us. R.D., still sitting on the stump, started singing: “Guide me over, great Jehovah, pilgrim through this barren land; I am weak but Thou art mighty, hold me with Thy power hand; bread of heaven, feed me till I want no more….” He stood up. Willie Mae, Joyce, and Nuthel joined him singing, and it was clear they had been singing like this all their lives. R.D.’s deep and gravelly voice kept the pulse of the song while the long, extended ummmhhmmms of Joyce, Willie Mae, and Nuthel were moans that sent shivers through me.

I listened, all the white folks listened, but none of us could follow to the country where the singers lived in this moment, a far country filled with the Spirit. That’s where that song was coming from—“under the water,” an African phrase, and the pain of being dragged in chains to this country. It was humbling just to hear it, sung out here in the woods on the burial ground. The scouts bowed their heads and held their hats with hands crossed in front of them.

Then R.D. began to pray, rhythmically, erasing any line between speech and song. “Our Father in heaven…” Nuthel, Willie Mae, and Joyce kept humming the melody they’d been singing while R.D. prayed right over them.

“Father, we give thanks for thy many blessings. Our Father, we give you thanks because your name is worthy to be praised, thank you, Father, for what our eyes have seen and our ears have heard, thank you again our Father for those who turned away from their busy schedules and come over today trying to help us reestablish this cemetery. You know our hearts, you know our heart’s desires, hmmhmm, we thank you, Father. We love you because you first loved us. We continue to hold up this bloodstained banner, and we pray, our Father, that you will bind us together in one band of Christian love. You said in your words, our Father, there is no chain stronger than its weakest link. We are weak, Father, but we know you are strong. And we ask you to hold us and keep our heads about us, Father, as we all head home. In the name of Jesus we pray, for his sake. Amen.”

All together we answer: “Amen.”

“Now let us be dismissed,” R.D. says, “and may the peace of God that passes all understanding keep our hearts and minds on Jesus Christ our Lord. Let us all sing now,” he said, and began “’Til We Meet Again,” a hymn that was easy to follow.

“’Til we meet again, ’til we meet again, God be with you, ’til we meet again….”

“There’re hot dogs on the table, buns, mustard, and relish,” my cousin Carolyn, Philip’s wife, said to the scouts, R.D., Mrs. Britton, Doug, and me, when we got back to my family’s house. Willie Mae had had to leave early, but the rest of us were hot, dirty, hungry, and thirsty. Carolyn had been cooking all morning, but when we arrived she seemed the picture of coolness. She greeted us with the screen door open. She was wearing a red, white, and blue American flag silk blouse and American flag earrings; her dark, curly hair was perfectly coiffed.

“Get your food in here and then you can bring it back outside to the picnic table,” she instructed as we filed in to wash our hands and get lunch. We got our plates of homemade beans and coleslaw and plucked hot dogs from a boiling pot of water on the stove and went outside. The lawn was grassy and shady under the massive pecan tree in back. There was a picnic table and, most importantly, a breeze.

Carolyn was used to entertaining with flair after years of being an officer’s wife and living in Europe, where Philip was stationed in the navy. She loved being a hostess and was good at making people of many backgrounds and nationalities feel welcome and comfortable. We ate lunch and drank iced tea, then enjoyed the brownies she’d baked; we relaxed and talked over what we’d seen at Love Cemetery, and the work that still needed doing.

Philip, Doug, and R.D. sat at the picnic table making plans to get out to Love again on Saturday—two days away—with a tractor and a brush hog, a machine with spinning blades that would clear out anything above ground level. They would use the tractor to tow it around the perimeter where there weren’t gravestones and markers that could be destroyed. For the foreseeable future, the work among the gravestones had to be done by hand. Some of the markers we found were little temporary funeral home markers only six inches high. Some headstones were only a foot high. At least one had been knocked down and was flat on the ground, and there could be others. R.D. assured us that there were a lot more graves back there; we’d only cleared a small part of the cemetery. We had to work carefully. He suggested waiting awhile before coming in with the heavy equipment.

The clearing we’d made by hand around Ohio Taylor’s gravestone would soon be reclaimed by the vines if we didn’t get back out there and keep cutting back the wisteria and pulling it out as much as we could. Philip had impressed on me that, when left wild, the East Texas wisteria could envelop and slowly pull on a seventy-foot pine until one day it would topple to the ground. Now that we’d started the job, they agreed, we had to keep after it.

In that moment I had a great hope: If we could work together like we had, side by side, if we could sweat out the pain of it, if we could sing together and pray together as we helped reclaim this graveyard for the Ancestors and their descendants—and for the larger community—then there was a chance we could begin to transform some of the mistrust and lack of understanding that has gotten in our way for more than 200 years. And if we could reestablish Love in this community, it would be possible anywhere.