FOUR

Borderlands,

Badlands, and the

Neutral Ground

So long as Texas is not seen as a Southern state, its people do not have to face the great moral evil of slavery and the bitter heritage of black-white relations that followed the defeat of the Confederacy in 1865. Texans are thus permitted to escape a major part of…the burden of Southern History.

—Randolph B. Campbell,

An Empire for Slavery

Stories rise out of a landscape as surely as plants grow out of the earth. History is made of stories, as are lives. All are grounded in the soil and the waters below. The landscape is our first context, the actual ground upon which our stories take place. So it’s time to understand the landscape of Harrison County out of which the story of Love Cemetery and the lives of Nuthel, Doris, R.D., and so many others have grown.

This place was given its character by the presence of Caddo Lake and its labyrinth of sloughs and bayous and by the vast pine forests that once blanketed this landscape. East Texas is part of the Gulf Coastal Plain and was once covered by warm shallow seas. Moreover, more than 65 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period, an enormous shallow sea stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Circle, submerging what is now Texas, as well as the middle section of what is now the United States and Canada. Long after those seas disappeared and the continents took on their current shapes, this small bit of land called East Texas produced enormous stands of pine forests; on the sandy ridges were longleaf pine, with loblolly and shortleaf pine below, then oak, hickory, and finally cypress and water tupelo in the bottomlands.13 Underneath it all was a sandy red clay and loam soil that would prove to be fertile ground for growing cotton. Below the sands and clays were limestones, shales, and deeper sands full of fossilized and compressed remains from those earlier millennia that could be extracted as coal, gas, and oil.

The earliest known inhabitants of the area were the tribes of the Caddo Confederacy, a matrilineal society of highly developed agriculturalists who lived in settled villages along the Red and the Sabine rivers, in what is now East Texas and Louisiana. The Caddo Confederacy was made up of about twenty-five tribes, of which the main three were the Natchitoches, the Hasinai, and the Kadohadocho. They were part of the ancient mound-building culture that flourished in the Mississippi and Ohio river valleys, stretching from Central America and Mexico up through Louisiana and Texas into the Midwest and as far north as Illinois and Minnesota.

The Caddo people had been living in northeast Texas, southwest Arkansas, and western Louisiana for roughly one thousand years at the time of the first contact with whites, when it was estimated that 200,000 Caddo people flourished in the area. Spanish explorers came through East Texas in the sixteenth century, hoping to find gold and the mythical passage to India. Traveling from Florida into northeast Texas with Hernando De Soto, who died en route, Luis de Moscoso, the leader who took over his expedition, came face-to-face with the Caddo in 1542. Moscoso’s party also seems to have come upon Caddo Lake, “Laguna Espanola,” and chose to travel south of the lake rather than attempt to cross it.

What looked like open, unoccupied land to the Spanish and to the immigrant communities that followed them was often land that had been carefully managed for over 1,000 years or, according to some estimates, for 1,500 to 3,500 years. Agriculturalists like the Caddo—river Indians famed for their fertile lands and abundant harvests—knew what crops to grow to add to the soil and when to stop growing to prevent soil depletion. They understood river bottomlands, animal habitat, migration, and space requirements for different species. They knew to leave enough land uncultivated to provide what we now call wildlife corridors and ranges—the stretches of land that animals need in order to thrive. To incoming white immigrants, the open land might have seemed uncultivated and free, there was so much of it. Some respected the boundaries of Indian villages, farms, and hunting grounds, but for the most part, whites continued the pattern of stealing land from Native people who laid the groundwork for this country and supported it for centuries.

Map of seventeenth-century Texas and the Mississippi River Valley

By 1760, France and Spain were fighting over land that belonged to neither power. The French had taken over enormous areas east of the Red River that would become the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. On the other side, the Spanish had claimed what would become Texas. The Caddo and other Native American tribes were caught between the two military powers. The Caddo were already fluent in French and were skilled traders. One of their main villages was at Natchitoches, on the Red River, where the French built an outpost. Across the river was New Spain. The constant shifting of boundaries between the Spanish and the French left a large swath of land over which neither government had jurisdiction.14

In the meantime, in 1803 Napoleon sold Louisiana to the United States, to finance his renewed war against the formerly enslaved people of what would become Haiti. The successful slave revolt that had begun in 1791 continued for twelve years. Napoleon attempted to take back the country and reestablish slavery, and was finally defeated in 1804. The rebels, formerly enslaved people, had won a huge and costly victory. They renamed the island Haiti, the original name the indigenous Arawak Indians had given it. No rebellion of enslaved people on this scale had ever succeeded before in North or South America. Slaveholders throughout the hemisphere were on notice.15

The United States became increasingly entangled in the border disputes between France and Spain. Finally, in 1806, a tacit agreement was reached: Spain would not allow its troops north and east of the Sabine River, and the French and the Americans would accept the Red River as their western boundary. In this way, a forty-mile-wide buffer zone, to be inhabited by no one, was created.

The Neutral Territory, as it was called, was an ill-defined, anarchic, ungovernable area that included Caddo Lake and Harrison County. It became known as the Badlands. The boundaries of the Neutral Territory were vague and constantly subject to renegotiation. The area soon attracted criminals on the run, horse thieves, land speculators, and pirates like the infamous Jean Lafitte, who smuggled African slaves into Louisiana through Galveston, Texas. There were law-abiding families who came just to find a place to live and who worked hard and were not criminals, but by and large the politics of the territory and the justice administered was catch as catch can, on the fly, and often settled by gunfights. Given that this was to have been a no-man’s-land, there weren’t laws to be administered and upheld. The letters GTT—“Gone to Texas”—were hand-lettered on notes and nailed up on many a door across the South. Such a note indicated to all, families and creditors alike, that the signer had skipped out on any and all obligations. To say that you had “gone to Texas” meant that you had gone beyond the law, to a foreign country where the laws of the United States did not apply. You were free from everything but the weight of your conscience. Faked deed purveyors poured into the territory and mixed with the Caddo tribes who had lived there for centuries. Vigilante justice ruled.

Meanwhile, the major cotton planters along the Atlantic Seaboard and in the Deep South were discovering that years of intensive cultivation was depleting the soil. East Texas with its rich, fertile land provided a tantalizing opportunity. Conventional white opinion held that chopping and picking cotton in the southern heat was too much for white people to bear. Still subscribing to that idea a century and a half later, Lydia Ball had told me that day at Blossom hall, “Why, honey, white people just can’t tolerate that heat!” She added that dark-skinned Africans, however, were made for such labor.

By the early nineteenth century, as a result of nearly three hundred years of European rationalization and a sixteenth-century mistranslation of the Biblical description of Noah’s son Ham as “black,” the enslavement of Africans had become acceptable, even “Christian.”16 Thanks to the towering work of English abolitionists like William Wilberforce and his band of Quakers, the African and Caribbean slave trade was outlawed by England in 1807, and even by the United States in 1808. Nonetheless, the institution of slavery was still legal.17 As the voices of abolitionists in the United States began to be raised, the issue of whether new states entering the Union would be “slave” or “free” became a central one. The admission of Texas in 1845 was not without controversy, given its unsavory reputation.

Randolph B. Campbell explains in An Empire for Slavery that New Spain had tolerated the ownership of slaves, but that Mexico, at least officially, did not. Shortly after gaining independence from Spain in 1821, the Mexican government outlawed slavery. Even though Texas was still part of Mexico, this territory was so large that laws against slavery could not be enforced effectively. Land grants continued to be given to settlers bringing slaves into Texas. In an attempt to increase Texas’s slave population and thereby enlarge its economy, Stephen F. Austin’s colony on the Brazos River gave immigrants eighty acres for each additional slave they brought in. This meant that in 1822, for example, one man was assigned 7,200 acres on the Brazos solely on the basis of his bringing ninety slaves with him from Georgia. He couldn’t occupy all the land he was given by Austin’s colony, it was so extensive.18

Another new arrival to what was still Mexico in 1834 was a man from Louisiana, W. T. “Buck” Scott, who would eventually give his name to Scottsville. Scott was attracted by the Neutral Territory’s “flexible” legal system, the good soil, and the ease with which he could claim 25,000 acres of land in the northeast quadrant of what would become Harrison County. One can surmise that Love Cemetery was once part of the land Scott claimed. He built his main plantation home—a wood frame house—on the site at Rock Springs where it stands to this day. Scott, like the rest of the people who poured into Mexican Texas, grabbed what he could. The fact that he had no title to the land didn’t stop him from building on it. He created his own fiefdom of five plantations, produced twelve children, and enslaved somewhere between one hundred and seven hundred people.

A year after Scott’s arrival, on July 1, 1835, the Caddo chief, Tashar, dispirited, hungry, and continually pushed back by whites like Scott and the hundreds who had preceded him, signed the Treaty of Cession selling the United States one million acres of Caddo land in Louisiana for $30,000. It’s not hard to imagine the chief’s despair. With the overwhelming influx of whites, there was less and less land for farming. Hunters had to travel longer and go farther afield, often for months at a time, to find bison, leaving the remaining tribe members increasingly vulnerable. Why not salvage something, he reasoned to the members of his tribe and the other elders. The Caddo way of life was being destroyed. Soon they would have nothing. The remaining Caddo accepted his decision. The Caddo too had a Trail of Tears.

Though it was thought that all the Caddo were forced onto a reservation in Oklahoma in 1859, in fact a handful remained at Caddo Lake and intermarried into the local population. Their descendants remain there to this day.

The 1835 treaty took place only months after Captain Albert Shreve, a steamboat builder and captain who gave his name to Shreveport, Louisiana, had completed years of dynamiting and breaking up enough of the Great Raft on the Red River to allow steamboat traffic through. The 160-mile log jam had blocked the waterways between Caddo Lake and the river for hundreds of years, making navigation impossible.

Shreve’s dynamite not only blasted a path through the log jam but also ensured the end of Caddo culture in East Texas. With news of the Red River being opened up for steamboat navigation, a new wave of white immigrants surged into Texas from the Old South like water bursting a levee. Not only was Texas land fertile, plentiful, and cheap, but now there was a waterway to transport goods to New Orleans.

Era No. 10, a nineteenth-century paddle steamer loaded with cotton. The Era traveled back and forth between Caddo Lake and New Orleans.

From this obscure part of Texas, Caddo Lake, boats traveled down the connecting Twelve-Mile Bayou out onto the Red River, briefly onto the Atchafalaya and, finally, onto the Mississippi River and on down to New Orleans. Within a few short years, the combination of rail and river transportation, bumper crops of cotton in the 1850s, and the stolen labor of slaves built the wealth of Marion County on the north shore of Caddo Lake and Harrison County on the south.

A year later, in 1836, after the Battle of the Alamo, when Texas declared itself a republic independent from Mexico, the constitution that was drafted legalized slavery but prohibited foreign slave trade. Planters from the South, as we’ve seen, were encouraged to bring with them the people they had enslaved. Free blacks could not live in Texas without the consent of the new Congress of the Republic of Texas. Years of war with Mexico followed. In fact, a new look at Texas history and the legendary Battle of the Alamo shows that the Texas fight for independence from Mexico had much more to do with the question of slavery than previously acknowledged. It was not the only reason for the break from Mexico, but it was a major factor.

The Republic was viewed with great suspicion by many. British abolitionists railed in the British parliament against granting the Republic of Texas diplomatic recognition. One of them, Benjamin Scoble, in 1837, called Texas “that robber state…settled by hordes of characterless villains, whose sole object has been to re-establish slavery and the slave trade.”19

In 1839, Frédéric Gaillardet, a French writer sympathetic to l’aristocratie and the new Republic, pointed out that Texas, with its rich soil and “location at the southern end of the American Union,” was indeed becoming a haven for slaveholding planters from the upper South: “In the enjoyment of this position lies the germ of Texas’ future greatness. It will become in the more or less distant future, the land of refuge for the American slaveholders; it will be the ally, the reserve force upon which they will rest…. If…that great association, the American Union, should be one day torn apart, Texas unquestionably would be in the forefront of the new confederacy, which would be formed by the Southern states from the debris of the old Union.”20

Amid the clamor and controversy, Texas was finally admitted to the United States as a slave state in 1845, the twenty-eighth state of the Union. Mexico had long accused Texas of being a crude cover for land speculators and slave traders who sought enormous profits and wanted to reopen the African slave trade.

The tumult continued after Texas came into the Union, and in 1858 John Marshall, editor of the Austin Texas State Gazette (but no relation to the man who gave Marshall, Texas, its name), claimed that Texas was destined to become the “Empire State of the South,” provided that the African slave trade could be reopened. Slavery was growing, but too slowly, Marshall wrote, “and until we reach somewhere in the vicinity of two million slaves, it is equally evident that such a thing as too many slaves in Texas is an absurdity.”21

The number of people held in slavery in North America’s “internal slave trade” grew from 1.5 million in 1820 to 4 million by 1860, the eve of the Civil War. It was this phenomenal growth of domestic slavery that allowed white Southerners to clear enormous tracts of land and extend the Cotton Kingdom from the Atlantic Coast across the entire South and eventually to East Texas.

By the 1840s, 60 percent of the world’s cotton was provided by the South, notes David Brion Davis, the author of Inhuman Bondage.22 The cheap American cotton that dominated the world market was the result of the cotton gin, water transport, and the use of slave labor. The South supplied cotton to New England, Britain, continental Europe, even Russia.

Aside from the land itself, slaves were the major form of wealth in the South, and owning them the means to prosperity. “Large planters soon ranked among America’s richest men…. By 1860, two-thirds of the wealthiest Americans lived in the South.”23 And despite the myth of the Southern slave economy as being backward and unproductive, it was, as Davis says, chillingly effective and brought in record profits during the antebellum years.

East Texas landowner W. T. Scott, the biggest slaveholder in Harrison County, was a prime example of someone who built up great wealth as a result of the international demand for cheap American cotton. Scott was one of the founders and owners of the early railroad in Harrison County, and in the late 1850s, he laid down track that ran directly from Marshall to the gin he owned seven miles to the east at Scottsville. From there, the train continued east and then turned north to Swanson’s Landing on Caddo Lake, where paddle steamers were waiting. Scott had the means to move his cotton to market quickly, first by train and then by paddle steamer to New Orleans, hence his becoming the largest and wealthiest slave owner in Harrison County before the Civil War.

On one of my earlier trips to East Texas, long before I knew anything about Love Cemetery, I discovered that it was from W. T. Scott’s son, Rip (R. R. Scott), that my great-grandfather, Stephen John Verhalen, had bought the acreage for his nursery. It had been one of Scott’s plantations, part of the Blossom head-right, a form of land grant used by the Republic of Texas based on the head of a family. I became uneasy. I wasn’t sure why. Though my great-grandfather had bought approximately 2,800 acres in 1900, well after the Civil War and Emancipation, I was dimly aware that he had built a large business in this eastern part of the county during the worst years of Jim Crow,24 the period marked by a collection of shamelessly racist laws that began to be passed around 1875 to undermine any gains made by African Americans during the years of Reconstruction immediately following the Civil War. The Jim Crow era lasted right up to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

I didn’t yet know about the “store system” or debt peonage. It too was very much a part of the Jim Crow era and was often as restrictive and cruel as the institution of slavery itself.25 “There are more Negroes held by these debt slavers than were actually owned as slaves” declared the Georgia Baptist Convention, in 1939.26

Only during this writing did one of my cousins tell me that the wages of field hands at the Verhalen Nursery were paid to one of the three stores in Scottsville, not directly to the workers, a common practice throughout the South. Over time, I learned the implications of this. Though some white storekeepers were known to help people and might see a farmer through a bad season, others became notorious for the ways they took advantage of people. I would hear local stories of storekeepers demanding—and getting—a deed of land as collateral for a ten-dollar loan or even burning down a house if the owner wouldn’t give over a deed as collateral for seed to start the planting season. By the 1940s, the Verhalen Nursery was paying its field hands directly, breaking with the store system that had prevailed since the demise of Reconstruction. Were the wages fair? I have reason to doubt it, but no proof. Were wages fair anywhere for African Americans in the 1940s? I doubt that too. Injustice knows every age, including ours. Roughly forty families were housed by the nursery and employed there, receiving some form of medical care when needed. But no matter. There was no way around what one of my older cousins told me about the nursery business participating in the store system. He knew, he told me, because he wrote out the checks for the field hands. He didn’t know what precipitated such a big change in how business was done, but there it was. That was about 1939.

I questioned how it was that the wages were paid to the storekeeper, not the field hands who earned it. “That’s how things were done in those days,” he answered, and then we put the subject aside. I put it aside. It made me uncomfortable. I couldn’t assign that information a place in a moral universe, so I whitewashed it. For a time. But I couldn’t forget what I’d been told. I saw how naïve I was to imagine that because no one in my family had enslaved people, somehow that meant my hands were clean. What my family did or did not do had nothing to do with me. I could no longer hide behind that excuse.

Debt peonage cropped up along with the adoption of the “black codes” of early Reconstruction. Emancipation was quickly countered by recalcitrant whites and Confederates stung by the Union’s defeat. African Americans were quickly denied the ability to vote, to serve on juries, and to attend school, among other things. Such was freedom after Emancipation.

The store system was part of the white reaction too, only the store system involves only debt. Debt peonage was a federal crime—it went further. It was widely used by southern whites to keep black labor and mobility under white control after Emancipation. With debt peonage, a person was physically restrained from leaving their “employer” until their debt was paid. It was debt tied to employment and to confinement. Debt peonage revolved around a person being physically restrained from leaving his or her employer until the debt was paid. The tentacles of debt peonage stretch out across the world and time. Debt peonage was, and remains today, slavery by another name. It continues to spread.27

To understand the real tragedy of the long Jim Crow era, you need to have a sense of the enormous hopes generated among African Americans immediately after Emancipation. For a short time after the Civil War, during Reconstruction, blacks held an array of elected offices. They served as judges, lieutenant governors, members of state legislatures and the U.S. Congress. The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified on March 30, 1870, prohibited depriving a citizen of his vote due to race, color, or condition of servitude. It essentially enfranchised black men. (Remember, no woman could vote until 1920, regardless of color.) During Reconstruction, approximately three-quarters of the registered voters in Harrison County were African Americans. Fifty-nine percent of the people in Harrison County were enslaved in 1860. They significantly outnumbered whites in the county and they voted. Marshall sent an African American state representative to the capital in Austin, as well as a black state senator, David Abner. Blacks were elected to a wide variety of offices in Harrison County too. African American children received their education in the Freedmen’s Bureau Schools set up by the federal government. Literacy was spreading, and with it, black land ownership was on the rise.

Land was a precious, hard-won commodity. The crushing story of formerly enslaved people being given “forty acres and a mule” at the end of the Civil War and then having that same land taken away from them was known throughout the South, fueling black farmers’ determination to buy their own land whenever they could. Formerly enslaved people were given forty acres and a mule, briefly, thanks to General Sherman’s special Field Orders, No. 15, issued in January 1865.

“Sherman’s Order was temporary and did grant each freed family forty acres of tillable land on islands,” the coast of Georgia, South Carolina, and the country bordering St. John’s River, Florida.28 The army also provided them with mules. After the assassination of President Lincoln, his successor, Andrew Johnson, revoked Sherman’s Orders over the repeated objections of his generals. Untold thousands of former slaves had followed Sherman’s march. Those who had been granted land had been living on it and working it for a year, along the coast in South Carolina and Florida, only to have their deeds taken back in one of the greatest treacheries of Andrew Johnson’s administration.

As soon as federal troops withdrew their protection from Harrison County in 1870 and Reconstruction began to be dismantled, southern whites began to enforce measures aimed at again disenfranchising black voters. These actions included poll taxes and literacy tests, as well as the use of violence, especially lynching, to intimidate blacks. Though statistics show only the number of lynchings that were actually reported, thousands of African Americans were lynched across the South, effectively extending a rule of terror that reverberates to this day. Taken together, black votes in the South were effectively eliminated until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.29

The white Harrison County town fathers were in the vanguard of these efforts. They had grown increasingly fearful, impotent, and angry as former slaves established themselves as a dynamic political force. To some of them, the rapid advancement of African Americans was intolerable. They organized the Citizen’s Party in 1876.30 (Some sources refer to it as the “White Citizen’s Party.”) By 1878, they had wrested control of the ballot box—in some cases, by literally stealing it. Once again, W. T. Scott, the county’s wealthiest antebellum planter and a three-term state senator during the 1850s, played a central role.

In 1936, a certain R. P. Littlejohn of Harrison County wrote A Brief History of the Days of Reconstruction in Harrison County, Texas. In it he explained how the white “gentlemen” of Harrison County “won” the elections in 1878. Given that white men were greatly outnumbered and that “it was impossible to defeat [blacks] at the polls by fair means,” Littlejohn wrote, the former town fathers decided that “any means we could adopt to overthrow that unscrupulous, thieving ring of carpet baggers would be just and right.” Formerly enslaved people were lumped into the category of northern carpetbaggers, thereby “justifying” all manner of activity.

As Littlejohn explained, “It devolved on this committee to have a watchful eye on political matters and especially elections.” The Citizen’s Party substituted fake ballots for legitimate ones. On Election Day they would mingle “among the negroes, ask to see their tickets and unknown to them would exchange our tickets for theirs, thus securing many votes for the Citizen’s Party.” After polls closed, members of the Citizen’s Party would steal the ballot box and replace it with a duplicate they had prepared.

Closer to our story, Littlejohn notes that W. T. Scott was himself “holding the election” in Scottsville. Near the end of voting day in 1878, he didn’t like the way things were unfolding so he got word to his fellow party members back in Marshall, seven miles west, that his “voting place was surrounded by Negroes who demanded that the votes be counted before those holding the election went to supper.”

“Those [Citizen’s Party] boys wanted a chance to swap a box that had been prepared for the regular box and told the Negroes they would go to supper and count the votes when they got back, but the Negroes would not let them out [with the ballot box]. So about fifteen of us secured an engine and caboose from the Railway Company (always willing to help in cases of emergency) and went to Scottsville.”

The Citizen’s Party men from Marshall got off the train a little way up the track from Scottsville and “took the negroes by surprise and surrounded them.” They freed the white men and saw to it that they could leave for supper as they had planned, with the ballot box. Littlejohn again: “When the votes were counted, though that was a large Negro precinct, it developed that the Citizens Party had carried it, by a large majority.” Littlejohn noted that “the ringleaders of the Negroes were arrested, tried, and fined.”

In the final paragraphs he tells how the Citizen’s Party broke up any “Negro meetings” they could find and added that “the Negroes were very ignorant in those days and much leniency was shown them on this account, but harsh measures were resorted to in some instances.” He said that it was easy to outvote the Republicans of those days by “changing Negro votes” and using “fictitious ballots, and other methods…until the majority of Negroes gave up trying to vote and finally were excluded in primary elections.” His brief history, written in 1936, closes with this final note: “Negroes have made wonderful progress since the days of Reconstruction, in education, acquisition of property…. They have accepted the political situation and no longer try to interfere with a white man’s government and as long as they maintain that attitude, the best element of whites bid them Godspeed.”

Littlejohn’s account could be dismissed as exaggeration were it not for countless other accounts that paint a similar picture. History is not a repository of lifeless archival information. It is a story and stories are alive. They keep taking hold of us until we can retell them in ways that point us toward a new understanding.

In the early 1980s, I had spent time in Harrison County, around Caddo Lake in particular, meeting and interviewing African American elders for a story I was working on. On those trips, I came to know Deacon Hagerty and his wife, Pammy, Mabel and Leon Rivers—Sam Adkins’s grandchildren, who cared for him at the end of his life—and Kizzie Mae Hicks. Their stories brought to life painful terms like disenfranchisement and land theft.

Deacon Hagerty, still tall, rail-thin, and erect at ninety-seven when I first met him, told me that he didn’t learn to read until World War I, when he was on the battlefields of France. There his commanding officer taught him to read by lantern light in his tent at night. He came back to East Texas a very different man. He was literate, he’d seen the larger world, he’d fought for our country. When he arrived back in Marshall in 1918, he told me, he went down to the courthouse to register to vote. He was greeted with barrels of shotguns lined up to meet him or any other black man who dared to try to vote. He knew those men and they knew him. He never forgot that, he said. Once off the battlefield, American guns were turned on him. Deacon Hagerty ended up working for the railroad and was a member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the famous black labor union.

It was also Deacon Hagerty who gave me a firsthand account of the workings of the “store system” that had so troubled me when I discovered that the Verhalen Nursery had participated in it.

He told me, “The storekeeper would give you a mule, a wagon. And then, time to pay, he’d say: ‘You owe me so many thousands of dollars, oh, you don’t have the money, well I’ll just have to take your land.’ Black folks didn’t understand the system and they didn’t know nothing, they couldn’t read and write. Storekeepers continued to take advantage of them, even after they turned ’em free. A lot of land got put together that way…yes it did, unless you had learned to read and write. I’m strong about that,” he told me. He had put his son through college. He had a daughter getting a master’s degree. He had a granddaughter with three degrees. He told me, “Most colored people didn’t have no one to help them at first.”

Deacon Hagerty told me that he was fortunate in his family, because his father “had a good white friend, Old Man Driscoll, quite nice, and he taught him how to own the land.” He let Deacon Hagerty’s father have a plot of land and told him, “I’m going to deed this land to you. Now you take it and raise your family on it.”

“My daddy bought the land from Driscoll cheap, two hundred acres. Driscoll set the price so he could afford it. He showed him how to do the paperwork and register a deed, how to handle and work two hundred acres of land and how to leave it for his children. Driscoll showed him how to do it, sure, that’s right, mmhm. That’s the way it was. When we was in the army, my brother went next to me. Driscoll told us, ‘When you boys come back out of the army, you take your discharge papers and go on down to the county and get them recorded so you get your benefits.’

“Driscoll helped me and my father. Old Man Driscoll’s father helped colored people too. They were some good white people, they weren’t all bad.

“In three more years of living, I’ll be one hundred,” Deacon Hagerty said. “If I make it, I will thank the Lord. We got to get together and pull together, black and white, everybody, we got to be all one nation. I’m strong about that. We got to come together, we got to work together on one accord, we’re all God’s children. That’s what the Lord said to do. He said we’d have to sit down together, reason things out. That’s what the Good Book tells us…we got to love one another.”

Then, after a pause, he asked with genuine bafflement and sincerity, “What is wrong with your people? Don’t white people read the Bible?”

“That’s a good question, Deacon Hagerty,” I said, but I had no answer.

The enormous importance Deacon Hagerty placed on education was echoed by almost all the African Americans I came to know in East Texas. Nuthel’s family had been gathering college degrees for generations. Nuthel’s aunt had a bachelor’s degree from Wiley—that meant graduating in approximately 1896. Education—even learning to read—had for the most part been forbidden to those enslaved. During Reconstruction, the fierce hunger for education could not be stopped. Dedicated teachers came to Marshall from around the country to teach in the Freedmen’s Schools—white teachers who were risking their lives to educate these children. Freedmen’s School teachers were insulted, sometimes shot at, and driven out of town. They also trained African American teachers, who continued schooling their newly freed communities, risking their lives to educate their people. Young African American people walked barefoot for miles to school. They too faced harassment and danger, but they could not be stopped.

In Leigh, Texas, between Scottsville and Caddo Lake, a dozen miles northeast of Marshall, neighbors and members of the historic African American Antioch Baptist Church banded together to work the fields of their pastor, Jim Patt, so he could go to Marshall for an education in the 1870s. Patt not only became literate and learned enough property law to be able to help his community prove their ownership of the land, but in 1881 he also became involved in the founding of Bishop College. Jim Patt taught his congregants how to read and write and how to register their deeds at the courthouse, while taking care of their spiritual needs as well.

By the end of Reconstruction in 1880, historian Steven Hahn notes, “owing to their many struggles for schooling and literacy…between 20 and 30% of African Americans over the age of ten in the former Confederate states could read and write. Between 1865 and 1880, more than fifty newspapers [were] edited, and at times owned, by African Americans.” Those numbers grew rapidly over the next two decades. People were on fire with freedom.31

Though some people learned to read during slavery, most could not. It was illegal to teach a slave to read; in some cases, doing so was punishable by death. After Emancipation as African Americans fed their hunger for learning, they were stymied by the white colleges and universities that barred them from attending. The need to remedy the situation prompted church groups and the Freedmen’s Bureau to start elementary schools, high schools, and colleges throughout the South as quickly as possible. It was specifically the Freedmen’s Aid Society of the United Methodist Church that started Wiley College in 1873, in Marshall. In 1907, Wiley College was the first recipient of an Andrew Carnegie library west of the Mississippi. Ironically, Wiley had a better library than the city of Marshall.

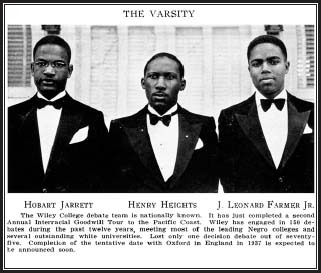

Gail Beil, a member of our Love Cemetery Committee, knew a good deal about Wiley’s surprising history through her friendship with James Farmer Jr., her involvement with Wiley, mentioned earlier, and her research for a book about James Farmer Jr. and his father. Farmer’s father, James Farmer Sr., was the first African American in Texas to earn a Ph.D. (Boston University, 1918) and was a professor at Wiley. James Farmer Jr. was born and raised in Marshall and graduated from Wiley in 1938. Though his early days there would be eclipsed by his later prominence in the civil rights movement as the founder of CORE and a leader of the Freedom Rides, Farmer had been a member of the famous Wiley College debate team that, in 1935, defeated the reigning national champion college debate team, the University of Southern California. Given that, in 1935, black teams were not allowed to debate white teams, Wiley’s victories became the stuff of a legend that grew from that famous victory in 1935 to their 1937 win over the Oxford University team, then on tour in the United States.32

The Wiley team was coached by the extraordinary Melvin B. Tolson, a poet and English professor who continued to have a deep influence on Farmer for the rest of his life. Farmer was fond of saying that after he beat Malcolm X in a debate for the fourth time, he thought Malcolm should just give up; Malcolm hadn’t been trained by Tolson, whose strict discipline and ferocious preparations made Wiley’s team famously unbeatable. Tolson, in turn, had been influenced by the Harlem Renaissance, spending summers in New York while finishing his master’s degree at Columbia University. Tolson taught his students about W. E. B. Du Bois, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and other great African American and African Caribbean thinkers and artists, bringing awareness of the Harlem Renaissance and the 1930s flowering of black intellectual and artistic culture to East Texas. It’s not hard to imagine that Tolson’s introduction of James Farmer Jr. to Henry David Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience could only have helped shape the course of the civil rights movement of the sixties.

Later, I would meet another member of that legendary team back in California: Rev. Hamilton Boswell, pastor emeritus of Jones Methodist Church in San Francisco and a leader in the San Francisco community, who also served ten years as the chaplain of the California State Assembly. The influence of Tolson’s debate team at Wiley made itself felt far beyond Marshall.

Boswell explained how in 1935, even though blacks were prohibited from debating whites, the Wiley team was so outstanding that it was informally invited to debate the University of Southern California through their mutual ties with the Methodist Church. Boswell was present at that electrifying debate in Los Angeles and was so inspired that he left school in California to attend a tiny black college in “Prejudice, Texas,” as he called it, to join the debate team with Farmer and to study under Melvin Tolson.

1935 Championship Debate Team, Wiley College, Marshall, Texas

As Gail Beil has noted, almost every Wiley debater during this period either observed or was threatened with lynching.33 Boswell, who had become one of Tolson’s star debaters by then, told me about a night when he and Farmer and Tolson found themselves driving into a lynching in progress in a little town between Marshall and Beaumont, where they had been competing.

“You see, I’m not what you might call a southerner,” Boswell told me, still very alert at ninety-three. “I was reared in California, and I had a reputation for fighting. I remember the southerners, Farmer and Tolson, as we were driving along, as we began to see the crowd gathering, they knew something was up. I was oblivious, didn’t know what was going on at first, until they said, ‘Hamilton, you get in that backseat and keep your mouth shut and let us handle it if there’s any trouble.’ They had faced this situation before. I was fresh in from California. They put me in the backseat to keep quiet, and I did. Nobody bothered us. We got through town.

“After driving on for a while, though, Tolson decided to turn around so we could see what had happened. By then most of the crowd had dispersed. There were only a few, very few people around that tree then. You could see the body hanging on the tree about fifty yards from the road we were traveling on. The dismemberment of the body. It was the worst thing I ever saw in my life. I still sometimes have nightmares about it.

“They had dismembered most of his fingers, his penis, toes. People took them for souvenirs. Souvenirs,” he repeated for emphasis, still shocked at ninety-three, as was I to hear this from a living witness.

“They had their children there to see the lynching. Carried them on their shoulders. Schoolchildren! The worst thing I ever saw.

“Tolson saw a man standing in the shadow, a black man. He went up and talked to him, and the man said the victim was his cousin and he would get him down. There was a relative waiting. Someone to cut him down and care for the body. Tolson decided that it was best to get out of there now that he knew that there was somebody there to take care of the body.”34

Rev. Boswell admitted to me that after experiences like that, he started to hate white people. It was when he realized that Jesus himself had been lynched that he was able to let go of those feelings. That’s when he felt called to become a pastor.

In that tumultuous period after the Civil War—in the 1870s and 1880s—African Americans were intent on educating themselves, and for the first time in the South, they were also beginning to acquire land to farm. People like Ohio Taylor, Lizzie Sparks, the Johnsons—Doris and R.D.’s grandparents—the Hendersons, and others, maybe even Wilson Love, Della’s father—managed, over time, to buy land together or adjacent to one another on the north side of Scott’s main plantation. The deeper I navigated into the history of this place, the clearer it became that Love Cemetery was indeed, as Nuthel had told me, the last vestige of that thriving black farm community. There was no little irony in the fact that almost all this land must have belonged, at one time, to W. T. Scott, the former slave owner and white supremacist politician. In 1872, according to one source, Scott was “brought low” by creditors, including Pendleton Murrah, the governor of Texas, and was forced to sell off parts of his holdings.35 This sale occurred around the time that African American farmers were buying land.

By November 1877, black farmers in Harrison County were meeting weekly. Steven Hahn, in A Nation Under Their Feet, notes that by 1890 the Colored Farmers’ Alliance could claim 90,000 members in Texas.36 A new militancy was growing, as African American landowners, tenant farmers, and sharecroppers took up issues ranging from low wages paid to cotton pickers to emigration to Liberia.

How did this little-noted rural activity affect the farmers around what became known as the Love place? I found no record of that, yet. But no amount of organization, education, and progress could keep out the larger forces at play. Hahn’s well-taken point is that vibrant organizing, thinking, and communicating were going on in the emerging black farming communities across the South, largely unnoticed by white people.

What happened to the community of farmers around Love Cemetery? I still had only fragments. Obviously, there is no single answer to that question. Even those families that had been able to hold on to their land, like Doris, R.D., and Albert Johnson’s, had not been able to keep the younger generations from seeking opportunities in large cities. The Depression and World War II had had their effect, taking many people off the farms or out of farming altogether. The difficulties of farming and bias against African Americans took their toll. And, always, there was the issue of land theft.

In contrast to Deacon Hagerty’s story about Old Man Driscoll, who had helped his family buy land and made sure they knew how to keep it, there was a story that another friend of mine, Kizzie Mae Hicks, had told me. The consensus in Uncertain, Texas, when I met her in 1983, was that Kizzie was “the best fry cook on Caddo Lake.” Over the years, Kizzie’s story became, for me, emblematic of land theft. This is how she’d told it to me one day, sitting in the Waterfront Café on Caddo Lake, where she was the cook at the time.

“Strange things happen when you live around a place like this for a long time. I used to work a second job cleaning house for a man who lived nearby. One day I was there cleaning and we got to talking. My family used to have a lot of land nearby, the Hicks, and some of my cousins still do. He remarked on that. I told him this story that came down in my family.

“After Emancipation, my great-grandfather, Jeff Hicks, put together a lot of land, three or four hundred acres, some say nearly a whole section of land, even though he’d been a slave. When he died, that land passed on to his children and some of it became my grandfather’s.

“Well, one day my grandmother was out plowing behind a mule and the mule ran off. She broke her leg and grandfather put her in the wagon and took her to the doctor. He had no money to pay for a doctor so he put up the deed to his land to get the doctor to treat my grandmama and set her leg. He paid the doctor off on time and went to get his deed but the doctor said my grandfather never paid his bill, so he’d just have to keep the title to his land. The doctor said he wouldn’t run my grandfather off, that he could stay on his land and sharecrop.

“It was the 1930s in East Texas. It was a black man’s word against a white’s. So that’s what my grandfather did, he became a sharecropper on his own land. Then my father became the sharecropper.

“My father hated sharecropping on that land. I will never forget the day he said he’d had enough. Said he wouldn’t sharecrop no more no matter what, he didn’t care, he couldn’t put up with it. He would never be able to get our land back, no matter how hard he worked or how many years he tried. He piled all our belongings into two wagons and we left. He bought a little land here near the lake and built the house I live in now with my children. It’s not much, but it’s ours.

“I told this man I was working for this story about how my grandfather lost his land and he said, yes, he imagined it was true. ‘Lotta land got put together like that. Nothin’ you can do about it.’

“The strange part was we kept talking and we figured out that the doctor who stole my grandfather’s land was the grandfather of the man I was talking to, the man whose house I was cleaning that day. In fact, that house I was cleaning was on the very piece of land that was stolen from my grandfather.”

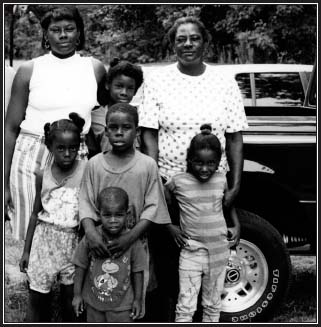

Kizzie Mae Hicks (r), her daughter Barbara Brooks (l), and Barbara’s children

Kizzie’s story took hold of me and kept working on me through the ensuing years and my regular visits back to visit family. I started checking records. First I found her great-grandfather in the 1870 census, the first time African Americans had last names in the eyes of the law. I started checking deed records and discovered that her great-grandfather, Jeff Hicks, had indeed owned over three hundred acres, if not more. In 1983, when I first tried to understand Kizzie’s story, I was naïve enough to think that black people had never owned parcels larger than a few acres. But through research, I discovered that in 1910 black Americans owned more farmland than at any time before or since—at least 15 million acres. Nearly all of it was in the South, according to the U.S. Agricultural Census. By 2000, blacks owned only 1.1 million of the country’s more than 1 billion acres of arable land.

In 2001, the Associated Press carried out a remarkable investigation that included interviews with more than a thousand people and examination of tens of thousands of public records in county courthouses and state and federal archives. The report, “Torn from the Land” by Associated Press reporters Todd Lewan and Dolores Barclay, documented 107 land takings in thirteen southern and border states. In those cases alone, 406 black landowners lost more than 24,000 acres of farm and timberland. Today, virtually all of this property, valued at tens of millions of dollars and growing, is owned by whites or by corporations. Thousands of additional reports of land takings remain to be investigated. Ray Winbush, director of Fisk University’s Institute of Race Relations, said the Associated Press findings “are just the tip of the iceberg of one of the biggest crimes of this country’s history.” And I might add, one of the least known and least understood.37

I ended up in the back office of a title company, where the staff let me sit for as long as I wanted with a long box of typed and handwritten index cards. One clerk told me to make myself comfortable and “have at it.” I discovered that the parcel of Kizzie’s grandfather, Gifford Hicks, changed hands time and time again as it was leased or sold. There was oil and gas all over East Texas, and Gifford Hicks’s parcel appeared to have some of it, or at least the likelihood of it.

It was like going through geological layers in time with names and stories painted across those cards like petroglyphs on a canyon wall: one person’s suicide, another family’s need to sell. The most unsettling of all the cards I found was the one in which I discovered that my own great-grandfather had once, briefly, owned Kizzie’s grandfather’s parcel. Our lives had crossed long before we met.

I’ve stayed in touch with Kizzie, and I try to see her whenever I’m in the area. The last time was at the Big Pine Lodge, overlooking the lake. I could see the waitress working her way over to our table. I quickly looked at the standard lake menu of catfish, shrimp, Gulf Coast oysters, or steak. Down at the bottom of the page, enclosed in a wide black box was a discomforting official warning about the mercury content in local fish.38 In fact, the catfish served at Big Pines Lodge and other restaurants around the lake no longer come from Caddo Lake, but are trucked in from catfish farms in Louisiana. For all its beauty, Caddo suffers from mercury poisoning. The biggest reserve of “dirty coal,” lignite, in the United States, is found near Caddo Lake. It’s mined and burned in nearby coal-fired plants for power generation. As beautiful as it is, Caddo Lake can no longer be described as pristine.39

Caddo Lake

Kizzie said that people who fish the lake, including her, don’t talk about this. She has kept fishing the lake through it all—acid rain, mercury poisoning. While Kizzie fishes some for enjoyment at this point in her life, when she was growing up, she and her father fished as a necessity, hunted too, to supplement their crops. Kizzie’s family was not alone in needing to hunt and fish. The lake and the woods still feed people; not everyone at Caddo fishes for sport or hunts for pleasure.

After we ordered our dinner of fried catfish, hush puppies, and coleslaw, Kizzie told me that increased fencing of land, the “Posted, Stay Out” signs, and increasing numbers of parcels designated as private hunting clubs and reserves had locked out more and more people. There were fewer and fewer places to hunt. She had seen it change in her lifetime. The commons that people depended on here had almost vanished but for this jewel—Caddo Lake.

“The fishing’s not as good anymore. The lake is low now—not what it used to be. Motorboats, all that gas and oil have hurt it. When I started fishing these parts, there was nothing but wagon roads to this place, nothing paved or black-topped, and you could always catch something. This place, the Waterfront, is on what we used to call Sand Banks. Every slough and bayou had a name given to it by the old colored. We called them something other than what’s on your map. We’ve got a whole different map of the same area—’course it’s not printed up, never will be.

“I have been on and around this lake most all my life. I’ve cooked at most of the lodges: Waterfront, Flying Fish, Shady Glade, Curley’s, and now the Big Pine. When I first started working, I never sat down like this. Couldn’t take a break, not even to eat, nothin’ but work, it was so busy.

“I made three dollars a day when I started, working from ten in the morning to ten at night. Did that for six days a week. After twenty years of working like that on my feet, I’ve got arthritis bad. I don’t want my daughter Barbara to ever have to work like that. Kids today hardly know how different the world is for them.”

Love Cemetery was one of the few tangible vestiges of that different world Kizzie was talking about. Here was another compelling reason to restore Love Cemetery. Kizzie said that younger generations didn’t know the extent of their ancestors’ suffering. They couldn’t, but they could learn their history. Wasn’t it just as important for them to know their ancestors’ hopes, their visions? Love Cemetery’s fragments and shards might be what was left of a community that had kept its connection with the land. That’s what Nuthel had been trying to help me understand when she spoke of the Ancestors or when she spoke of the peace and beauty of Love Cemetery. That’s what needed to be remembered and marked and protected. That’s what drew Doris, R.D., Willie Mae, Albert, Clauddie May, and Joyce: that long-ago vision of community that their Ancestors offered them, and a place to remember and honor them. By reclaiming the cemetery, they could reclaim a part of themselves. Only now, it would take all of us to make it happen, young and old, all races, to get it untangled and cleared out. This was the story. This was the story that needed telling, the story of the clearing and what it takes to reclaim the ground.