SEVEN

“You Got to

Stay on Board”

“To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul.”

Simone Weil

When I woke up, Sam Adkins’s words were with me still: “You got to choose love.” Perhaps they had never left me. In order to “choose love” that morning, I would have to go to Shiloh Baptist Church and try to speak with Doris after the service. I needed to pray with community, not turn away from them.

I went downstairs to the big front porch and found Madelon sitting in the old brown rocking chair with the cracked and faded red leather cushions. She sat with her legs tucked underneath her, while Ben leaned back, a little precariously, in a tubular aluminum chair. In the background, an aged floor fan whirred noisily and stirred the air. Creamy gardenia blossoms heavy with sweetness weighed down the branches of a bush off to one side.

I’d already told Ben and Madelon that we were not going to film the service at Shiloh this morning. Even though the minister had given us permission, I needed to show up by myself, unburdened with cameras and recorders. They were relieved to not have to load gear and set up in a new location. We had a quick breakfast together of toast and cantaloupe, then I took off for Shiloh alone.

The organ had just started up as I slipped through the swinging back doors from the vestibule into the church. Doris was sitting up front in her usual spot in the front row, dressed in a white suit with long fringe falling from the shoulders. She turned around and nodded when she saw me. Willie Mae Brown was in the row behind me with a few other women whom I’d seen before at services. I relaxed, glad to be there after all.

After the service, I immediately went up to Doris and asked if she had time to speak with me. She stood still for a moment and then said, “Well, I suppose we could do that, alright.” She warned me that I would have to wait for twenty to thirty minutes. As an officer of the church and the secretary of the congregation, she had a series of responsibilities to discharge first. I told her I’d be glad to wait.

The service had been conducted by a visiting preacher who seemed to be waiting around for someone himself. I went up to thank him for his remarks about the passage “Without a vision, the people perish,” and somehow we ended up in a wide-ranging theological discussion. He eventually changed the subject.

“Are you waiting for Doris Vittatoe?” he asked.

I told him I was.

“You know,” he said, “I heard that somebody asked her to get everyone to sign over their rights to Love Cemetery.”

I felt the blood leaving my face. I could hardly believe the level of misunderstanding that this had escalated into within twenty-four hours. He went on. “You hear anything about that?”

No, I told him, I hadn’t heard that. It made no sense to me. There must be a misunderstanding, I said. I thanked him for visiting with me and left the vestibule.

I went outside to wait in the 101-degree heat. I found a towel in the trunk of my rental car and spread it out under a sweet gum tree on the church’s newly mowed lawn. I was rattled by the minister’s comments. Had he been testing me, knowing that I was the alleged culprit in the rumor? Or was he genuinely unaware that I was involved with Love Cemetery? I couldn’t tell. I didn’t know how to read the signs. What I did grasp immediately was that this small black church community had a swift and efficient way to get the word out when one of the their members was troubled or felt threatened.

There was an undeniable value to this reaction. The genius of the black church lay in its response to the lives of its people. It had grown beyond itself to become a way of life that carried people through enslavement, through Emancipation and Reconstruction, and through the decades of upheaval, migration, lynchings, injustice, and discrimination that followed. The African American church was the alchemical vessel in which elements of the old African spiritual culture transformed the Christianity imposed from slave days into something life-sustaining and unique. The church was the place where the community was “built up,” as R.D. would say.

That morning it had been announced in church that the son of a congregation member had just graduated from the University of Texas law school, passed his bar exam, and taken his first job with a law firm in Austin. Everyone burst into applause. Good news was celebrated; sorrow was contained.

But I was startled and disturbed by the rumor’s speed, power, and inaccuracy. It had already passed right by the actual event and taken on a life of its own. It let me know that the misunderstanding between Doris and me was even more complicated than I had imagined.

Doris finally came through the doors of the church and joined me on the grass, spreading out a towel to sit on too. She seemed as puzzled as I was. We started out with small talk: “How are you doing?” “How are you doing?” As soon as I felt it appropriate, I repeated my apology from the day before for whatever I might have done to offend her. I was willing to be instructed. Would she please tell me what happened from her perspective?

For the next half-hour, Doris and I spoke cordially. But no matter how hard she tried to tell me what had happened from her side, I couldn’t understand. Nor, I knew, could she understand what I was saying. We both were trying to speak truthfully and clearly, but neither one had the words to articulate why we each felt so wounded and confused. We were two people trying to speak to each other under water. Everything was garbled.

It became clear the more we struggled to talk that a phone message I’d left on her machine a week earlier asking her to help me get people’s signatures on the releases had touched a raw nerve. Doris had fallen back on her one experience as a movie extra. She had not been asked to sign anything back then, so why now? I countered by talking about the changing nature of the media today and the litigious bent of our society. The stately sweet gum tree was our only witness as we rehashed our positions. When I spoke, Doris listened carefully, nodding her head, and when she spoke, I did my best to hear her without resistance or reaction. But something essential was missing.

“I understand that friends have misunderstandings,” Doris said finally. “People make mistakes,” she added softly, “they misinterpret each other.” She seemed to accept the fact that I had meant no harm.

I heaved a sigh of relief. It seemed that she at least understood that nothing I had done was intentional. And yet, I sensed that we were in the magnetic pull of something so much larger than the two of us that we could not possibly make out its shape.

Doris and I walked to our cars. She got in hers and was about to turn the key in the ignition when I knocked on her driver’s window. She rolled it down.

My words tumbled out. “Doris, please understand. I don’t care about the release,” I said. “It’s beside the point now. Forget it. The whole documentary idea was just a dream anyway. I got ahead of myself. I’m a writer, not a filmmaker.” I paused for breath. “The most important thing to me is our friendship. Can you understand that?”

She nodded, but I couldn’t read her face.

I was over half an hour late for an interview with R.D. back at my cousins’ house. I couldn’t have left Doris any sooner. Madelon and Ben would have set up the camera and microphone by now. I checked my voice mail as I drove away from the church. There was an impatient message from Ben wondering where I was.

I flew through a tunnel of tall East Texas piney woods, then past a new clear-cut, a red dirt cutout on my right, then bore down on the old Motley cemetery (black), then the woods again, a field of locust trees, a house. I rolled down a gentle hillside and crossed over Harrison Bayou as it ran out to Caddo Lake. Cleared pastures whooshed by on both sides; I passed my great-uncle Peter Fax’s farm in a heartbeat. I glimpsed the rusted-out, honeysuckle-entwined gate to Verhalen Lake. Rock Springs Cemetery (black) loomed on the other side of the fence from the Scott cemetery (white). I caught a flash of marble angel wings, and then the springs for which people settled here flowing under a wisteria-covered pagoda. I crested the hill, where I had to slow down and turn left. This hill was the highest point in Harrison County, and hence determined which way the waters would drain. East, all the waters ran into Harrison Bayou and Caddo Lake. West, they drained into the Sabine River in adjacent Panola County. On the right, wisteria grew thirty feet high and more, climbed the telephone pole, wrapped itself on the line, and spread over the fifty-foot pines. On the left were the homes of two more of my Verhalen cousins. I felt the rumble of tires running over loose railroad ties and braked hard as I crossed the tracks, coming up on the Scottsville Community Center and the old Verhalen Nursery barn still falling in on itself, waiting to be cleared away. The nursery closed in 1976. I glided by a tranquil marsh, a small, still lake with two white egrets flying low over their own reflections. Tall cumulus clouds rested on its surface. I sped past the two-fire-truck barn and down between a mile of white-fenced pasture on the right and a fringe of woods on the left, thinned so you could see the pastures just on the other side of what used to be my family’s flower fields—fields of jonquils, King Alfred daffodils, narcissus, roses, wisteria, balled stock, Cedars of Lebanon, Voorhees Cedar, privet, American hollies, nandina—I didn’t know the names of all they grew. Only that I still hurt inside. Only that I still didn’t understand what had happened with Doris.

As I turned into the drive and pulled up to the house, I could see Ben filming a conversation between R.D. and Philip. They were sitting comfortably in the shade of the long front porch. Madelon held the boom-mounted microphone between them, out of camera range. The crunch of my tires on gravel interrupted their recording. Ben looked as if he’d relaxed since he left the voice mail on my cell phone. A warm wave of pleasure washed over me. My family, R.D., everyone seemed happy and engaged. I parked under some Spanish oaks where a mockingbird was singing.

R.D. seemed glad to see me. I detected none of the caution I’d sensed from Doris, but I didn’t know R.D. as well. I apologized for being late and added that I’d had a little misunderstanding with Doris and had stayed at church to speak with her since I would leaving town tomorrow.

R.D. leaned back a little in the brown rocking chair and smiled. I thought what I said had gone by him and was relieved that he made nothing of it. He and Philip went back to their conversation as I pulled up a chair and sat down with them. Ben signaled to Madelon that he was recording again, and she unobtrusively raised the mike. R.D. turned to me.

“Look, I’m not responsible, China, how you treat me. But I am responsible for how I treat you. The only thing we really have to do is trust.”

I recognized from R.D.’s cadence that he had started in on a spontaneous, personal sermon.

“You have to have faith. Faith is the substance of things unseen,” he continued. “I don’t see it but I just have a feeling. That’s faith. And that’s where he wants all of his children to be, in faith. And if we keep the faith in Jesus Christ, we’ll be able to weather the storm.

“If you remember the story when Paul was in that shipwreck, they got out on the ocean and ran into a storm that tore up that ship, and Paul got a word from God tellin’ him, ‘Paul, tell your passengers to stay on board. If they stay on board, no one will be lost. Although the ship is tore up, you got to stay on board.’ All them in the water, everyone had his hand on a piece of that boat, holdin’ on. Now what you think about that? They were a-cryin’ and a-sobbin’…sure they were goin’ to drown, but they stayed on board!”

I was aware of nothing but R.D.’s voice resonating between the arches of the porch, giving me something to hold on to.

“That’s the only thing you got to do—‘stay on board’—put your faith and trust in him, and he will see you through. It may seem hopeless, you may not see your way out, but all you got to do is trust in him. He said, ‘I’m the way maker, I make ways out of no way. When you can’t see your way, that’s what my eyes are for. I got eyes that never shut.’”

There was nothing I could say but “thank you, R.D., I needed that.” I was amazed by how thoroughly he seemed to understand that I was struggling, though I had said nothing to him about anything. He was telling me through his own language of parable that giving up was not an option. That I didn’t need to figure everything out. I didn’t need to understand why he was telling me these things, whether his sermonizing was a coincidence, or if it was just the way he spoke to everyone, or if he knew something that I didn’t. It didn’t matter, it was a gift to me in that moment. I just needed to “stay on board.”

By late afternoon, a thunderstorm was moving into the area, and there were severe-weather warnings posted. Thunder rumbled, a light rain fell, then stopped close to six in the evening. At the last minute, Philip’s sister, our cousin Mary Lou, called up with an offer Ben and Madelon and I could not resist, exhausted though we all were. She and her husband, Charlie Reeves, an avid bass fisherman in his late fifties, would take us out on Caddo Lake in their boat. Then we could have catfish at Johnson’s Landing, overlooking the bayou. Could we meet them in half an hour at the boat landing for a run? We could.

We were out on the water by seven in the evening, when the light was glowing pink and gold. Charlie was up front, Mary Lou in a seat behind him, next were Madelon and me with Ben just behind us, in the last seat, his arms around us both, his head touching Madelon’s. A green, violet, rose, blue, and gold rainbow shone over Mary Lou’s head.

Madelon and I hadn’t been to the lake together since we went canoeing here twenty years earlier, the summer before she left for college. The dark-haired woman in her mid-thirties sitting next to me was such a different person from the quiet seventeen-year-old who had drunk in the wild beauty of Caddo Lake twenty years ago. She had crossed so many waters since then. I wondered if she was also remembering our last time together on this lake.

I remembered how all those years ago we had started out before dawn. Just as we paddled out of a bald cypress grove into open water, the sun rose, pulsing and blinding us with a light so fierce that, for a moment, we could see nothing and had to stop. Then the sun caught the early mist and burned it off in a blaze of mauves, salmons, and pinks—fire on the water.

As the sun rose, the birds started up, first only one or two but soon a chorus that seemed to wake up the frogs and set the insects buzzing. We started paddling again, moving slowly into the revelation that surrounded us. Rising still, the sun scattered its light into a million tiny mirrors rippling into reflections on the steely green surface, reflecting so much brightness that my eyes could barely take it in. Our guide disappeared from view in the labyrinthine bayous. I asked Madelon, in the bow, to stop paddling. I was blinded. I closed my eyes and rested my paddle across my knees. The canoe rocked gently from side to side as we sat together quietly, breathing, feeling the warm honeyed light pour over us, a benediction, until the boat was still. By the time I opened my eyes, the dark greens and reds of cypress were paling fast, the gray-green of mosses fading. The world was changing every second, turning and turning, no way to stop it.

I felt the landscape breathe—the birds sailed off on its exhalation, then settled back down on the branches, its inhalation. We were part of this great breathing out over the waters of creation. For a moment it was easy to understand that everything continued, nothing was ever over.

“Mom, look!” Madelon cried, bringing my attention into the boat. “Something’s moving, in the duckweed, there.” She asked if I could see the tiny brilliant yellow beads that had appeared on the surface. I could see tiny movements all over the mantle of duckweed, making it ripple and come alive. “Watch,” Madelon said. “Frogs, Mom, there’s hundreds of them. It’s their eyes we’re seeing. Just their eyes, moving.”

We started paddling again. I had to shade my eyes to read the water, the light was still so blinding. I thought we’d lost our guide altogether, he’d surged so far ahead, until I noticed that there was a ribbon of darkness moving across the surface, a hundred or so feet ahead. It was opening and closing, opening and closing. I whispered to Madelon. She saw it too. It was the wake of our guide’s canoe folding back in on itself, showing us the way back. That’s what we followed—that darkening of the water, its stirring. It was all we could see, but it was enough. A line from the old hymn “God’s Gonna Trouble the Waters” came back to me.

All these years later, Caddo still enchanted me. Whatever had been unsettled in me back on land was washed away in the spray of the turns Charlie took us through. We motored between two islands, approaching the favorite bass fishing spot he wanted to show Ben. Charlie cut the motor and pulled out fishing poles for himself and Ben. Suddenly we were bathed in the lake’s quiet—and the sounds of frogs. Mary Lou was quiet also. Madelon smiled. We drifted slowly past pale yellow lotus blossoms. The lake’s current was all that moved us now, and we were free to marvel at the way water beaded on the two-foot-wide lily pads. Refracted in those drops of water we could see our boat with Madelon leaning over the side to marvel at their jewel-like clarity, and me, behind her, worlds within worlds.

The next day, Ben and Madelon went back to Dallas to visit their grandmother, my mother, Ruth Verhalen Langdon. I stayed over in Scottsville to finish up my research as best I could and pick up the pieces of the story. I still felt storm-tossed, but I saw a way to “stay on board:” go back to the early history of Love Cemetery. The obligation I felt I had to the Ancestors themselves didn’t stop with the restoration of the cemetery. I also needed to piece together the untold story of this place, its secret history. I wanted to understand how I fit into it—if, indeed, I had a place at all or if, as Doris had blurted out, I was not needed.

I planned to drive to Dallas that evening. With one day left in East Texas, I quickly packed and drove a few miles to Marshall, the county seat. The courthouse had become a familiar haunt from the many hours I’d spent researching the history of Kizzie’s grandfather’s land. That day, as I walked down the white-walled, beige-wainscoted hall, I could see, through the double glass doors, that the county clerk’s office was unusually busy.

When I walked in, the room was packed with fifty or sixty people. Rollers squealed and made tiny screeches as people pulled out volumes of records that weighed ten to fifteen pounds each. They were so heavy they had to be stored horizontally. Three copy machines whined and clicked steadily in the background. People were standing in lines to use them. The room was a beehive.

When I got to a table with the volume I needed, I asked the woman next to me why it was so crowded. She told me that she was a landwoman—almost everyone in the office that morning was a landman or woman—and that she was researching oil and gas leases and mineral rights. The man on the other side of me was from California. From what she said, I gathered that these folks were tracing the sometimes impossibly tangled threads of land ownership in East Texas in hopes that they could discover leases that were still available or overlooked mineral rights that might be purchased. This was all part of a general frenzy to reexamine existing domestic supplies of oil and natural gas and to find new ones. The price of crude had taken off with the invasion of Iraq. With new technology, there was hope of getting more oil and gas out of old wells, and the funds were available to make it a priority. The landpeople were either freelancers or employees of any number of oil companies, land speculators, investment groups—anyone, really, who recognized the skyrocketing value of domestic properties that had any potential of yielding up more oil or natural gas. I thanked her for the lesson and got to work.

The landman from California showed me how to handle the heavy volumes and remove the pages I needed. I did manage to turn up a deed record for Della Love’s father, Wilson Love: a purchase of 225 acres northeast of Marshall with three partners, and a second deed as well, of a 56½-acre purchase. I looked up the original deed to the cemetery again. It was as I had recalled: a “burial plot,” dated August 9, 1904, when Della deeded the land to the Love Colored Burial Association. But where did Della get the land she deeded Love? Had her father willed her some of his property? She was born the year he died. Had she bought it herself, like Lizzie Sparks, Nuthel’s grandmother, was said to have done with her farm nearby?

I asked the landman from California how one went about getting a photocopy of a record under the circumstances.

“We’re on the honor system here,” he explained, “it’s so crowded. You make your own copies and just keep track of how many. Put the pages back where you got them.”

The honor system? Fortunes could be made and destroyed here, depending on these records. What was to prevent an attractive record from simply disappearing?

While I waited in line, first to make the photocopy, then to pay for it, I ran through the story as I had pieced it together so far.

Wilson Love, Della’s father, was reportedly a free black man, born in 1829. I had learned from materials in the County Historical Society that his father was Robert Love, an Irishman who owned a plantation in the western part of Harrison County. His mother, whose name is lost, was one of Robert Love’s enslaved African women, a “house slave.”

As the son of a white plantation owner, Wilson might have been brought up outside of slavery altogether as a free black man or been given his freedom at some later point. Before the Civil War, free black men were rare. Texas had outlawed their entry, perceiving them as dangerous and liable to give enslaved people “ideas.” The settlers were already having problems with their labor force running away to Mexico, where slavery had been outlawed in 1821, as I’d discovered earlier.

In the only photograph of Wilson Love that I could find, he gazes forcefully at the camera. He has high, sculpted cheekbones and a carefully trimmed goatee. His brother, Nathaniel or Nat Love, was the famous black cowboy “Deadwood Dick,” who rode throughout the West and was befriended by the likes of Wyatt Earp. By now, little about the Loves could surprise me. For example, I discovered that Wilson’s first wife was named Phoebe Love before Wilson married her. She had apparently once belonged to a different family of white slaveholding Loves. Might they already have been related?

Sometime in the 1870s, after fathering several children with her, Wilson left Phoebe and married Sarah Williams. By then, he and his partners had purchased nearly three hundred acres in the northeast part of the county. Still, one cannot conclude that this is the area where Love Cemetery is found. There are thousands of acres in the northeast part of the county, and there were Loves up around Caddo Lake, also northeast of Marshall, both black and white families. The Love I tracked down claimed no relation to Della and her father’s line.

I wanted to assume that the area around Love belonged to Della’s father and that it was passed on to her when he died.

I was unable to find out if Love Cemetery corresponds with land that was owned by Wilson Love and his partners in the 1870s. It’s reasonable to assume that there’s some connection; however, there may be no connection, no matter how reasonable the assumption might seem. Tracing land ownership in East Texas was famously frustrating, with all its dead ends, loopholes, missing pieces of information, and missing records, to say nothing of the number of nineteenth-century courthouses that burned down. In one fire, only records of black land ownership burned.

The nineteenth-century maps that I found years ago showed a lot of “invalid” surveys. It was explained that an “invalid” survey was a nice way of saying that the question of ownership had come to blows, generally in a gunfight. In some cases, the name on the “valid” survey was actually a record of who was the best shot, not who had the legitimate claim. The gentleman who explained these things refused to be quoted or named, since clearing titles was such a loaded subject still.

Years ago, one of the former owners of a local title company in Marshall told me that a lot of black land ownership was put together in the 1870s and the 1880s by former slaveholders who had fathered black children. They wanted to help their offspring once they saw how difficult it was for African Americans to establish themselves.42

Some African Americans (like Deacon Hagerty) spoke of white friends and white relatives who helped their ancestors get their own land. Yet many African Americans acquired land with no help from white people, only by dint of phenomenally hard work, not only farming but hauling, clearing, sewing, cleaning—almost any manual labor. One African American family showed me a deed carefully handed down in their family that showed that they had bought and paid for their land with bales of cotton.

In 1883, Wilson and Sarah Williams Love had twin girls, Della and Stella. Wilson died at the age of fifty-one that same year. I’d already found out that he had been declared mentally incompetent by the Harrison County courts in 1882, but I hadn’t been able to find out anything about the nature of Wilson’s breakdown. Was it really mental illness, or might it have been a device used by family members to gain control of his estate? The two wives fought to be appointed administrator of his estate. A court battle ensued, with an administrator finally appointed in 1890. Though I looked it up again that morning, I could still find no record of the disposition of Wilson Love’s estate. I could not confirm whether Della had, in fact, inherited Wilson’s land. Yet she clearly must have owned enough land by 1904 to bequeath the small parcel to the Love Colored Burial Association. Della, according to a family account, married Lee Walker and moved to Oklahoma, where they had five children and lived on a Native American reservation in Chickasaw County. According to the family history, Della died in 1920 from poisoning.

By now I’d made the photocopies of the deed records I had pulled and had returned the originals and put the oversized volume back in its place at the county clerk’s office. The room was gradually emptying, as people headed out for lunch. There were still a few people ahead of me in the line to pay for the copies, though. I stood there wondering whether this flurry of research on Della Love was necessary that morning or whether it was a distraction from thinking about what had happened with Doris. I asked myself what I hoped to find embedded in these pages covered with the tight, formal, extraordinarily curvilinear nineteenth-century handwriting.

I wanted confirmation of the hidden story that existed among the shards and fragments we had been discovering at the cemetery, among the memories of the elders and in the scraps of records here in the courthouse. I wanted to know more about the secret history of what seemed to have been a thriving black farm community that had existed in eastern Harrison County from sometime after the Civil War until sometime in the 1950s or 1960s—the community that Doris’s great-grandfather, Ohio Taylor, and Nuthel’s grandmother, Lizzie Sparks, were part of. Sabine Farms of the 1930s—the ten-thousand-acre resettlement project for black farmers—we knew about, but the area known as Love seemed to have left no written trace.43

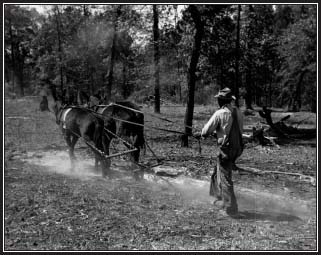

Sabine Farms, Marshall, Texas, 1930s

But I was beginning to understand that I was looking in the wrong place. There was an inherent problem in trying to coax the story of the black experience from these records. Here the story would be told by the silences, the omissions, the gaps in the records, what was missing. The records did not say whether a title was obtained ethically. They didn’t indicate whether a transaction was proper or if it was an egregious theft. The records, I realized, were the victor’s story. They were elaborate lists of who ended up with the title, not whether they had gained the title legally or ethically. That information was not recorded.

Finally it was my turn at the counter. Since there was no one in the line behind me, I had a moment to chat with the clerk, a woman about my age. I told her about Della Love and the difficulty I’d had finding a record of her ownership of the parcel from which she had deeded the acreage to Love Cemetery. She had no suggestions other than visiting the Historical Society, which was my next stop anyway. I commented on how packed with landpeople the office had been just moments ago. That was the way things were lately, she allowed. Then, in a quiet voice, she told me that there was a troubling side to all this activity. The landpeople at work here were scouting for a number of large corporations that were intensely interested in oil leases and mineral rights. The clerk—who asked me not to use her name when I wrote about this—was aware of cases of elderly people, especially black elders, who had accepted offers to sell the mineral rights to land they were living on, only to discover that because of some loophole, they had sold the land itself and suddenly had nowhere to live. The kind of land theft that had haunted me in the years since I heard Kizzie’s story was still taking place.

Later, I would speak with Spencer Wood, a professor who is a nationally recognized expert on black farmers and black land ownership.44 Spencer confirmed that while it might not be possible to verify stories like the one the clerk told me that day in Marshall or the one that Kizzie had shared with me earlier, both of them were, as he put it, “completely in keeping with a pattern of deceit and depredation that has led to a lot of black people losing their land.”45 In the end, the name on the deed is all that counts, not how it got there.

The pattern Spencer spoke of was as old as Reconstruction. Like segregation, disenfranchisement, and lynching, land theft had grown and thrived in the long shadow that slavery still cast—in spite of its abolition. In fact, all of these horrors could be seen as responses to the new possibilities that had opened to African Americans after Emancipation, even as forms of revenge for daring to even begin to claim the rights of education, the vote, ownership of property, employment, freedom of movement, and equal opportunity.

I left the courthouse sick at heart. At a moment like this, racism seemed so deeply rooted in—what? Society? The System? These were abstractions. If racism lived anywhere, it was inside each of us, sometimes consciously, often unconsciously. With racism rooted inside us and cultivated over centuries, we have institutionalized our prejudice and built white bias and privilege so thoroughly into the structures of our society that we mistake it for normalcy. Like the wisteria at the cemetery, perhaps we’ll never be rid of it. Our only hope might be to keep attending to it, trimming it here, uprooting it there, cutting it back, cutting it back, and contending with it.

From the county clerk’s office, I went a few blocks north to the train station and the old Ginocchio Hotel, which housed the Harrison County Historical Society Library and Museum. The volunteer librarian, white-haired Edna Sorber, with her bright blue eyes, was a trained librarian by profession. It was Edna who had helped me find everything I’d gathered about the Love family. She introduced me to their library.

Edna had nothing new to tell me but suggested I talk to Jimmy Oliphant before I left town. Jimmy was a retired military man whose ancestors on both sides had owned slaves. Like Edna, he volunteered at the Historical Society. When she told me about the unusual task he had taken on, the way another person might go on pilgrimage or join the Peace Corps, I was impressed. Jimmy had decided to find, record, and index the name of every single person who had been enslaved in Harrison County. Edna thought maybe he’d come across someone in the Love family, or something about Robert Love’s plantation.

Jimmy was sitting in an old-fashioned wooden library chair near the corner of a long library table, wearing a gray shirt the color of his hair, and jeans and boots. He unfolded his tall frame and stood up to greet me, asking after my family. I sat down across from him, where the mid-afternoon light streamed through the long casement windows.

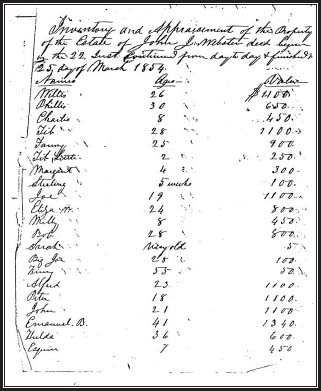

Jimmy used deeds, wills, bills of sale—anything that listed slaves—as a source for names. Until the census of 1870, enslaved people did not have last names, so Jimmy was compiling an index of first names. As a volunteer at the Historical Society, he had taken it upon himself to answer every query that came in from African Americans wanting to trace their ancestry. He showed me what he was working on that day.

“I got someone writing me who’s looking for a ‘Henry Cook,’” he said in a gravelly voice with a southern drawl. “They know he was born in 1855.” He pointed to a stack of paper. “So I got my list out and I went lookin’ at the Henrys. There’s about a dozen Henrys on there, but only one of them was born in 1855.” He grinned, deepening the creases in his well-worn face. But the grin faded as he went on. “I found him in some property records dated 1859. He was four years old and belonged to the William J. Blocker estate.”

The 1870 census, which listed black peoples’ full names, was first census after the Civil War. Newly freed people made up names, took names of their heroes, of occupations, sometimes of former owners if they’d been halfway decent. After finding him in the 1859 property record, Jimmy then found Henry’s last name in the 1870 census by looking for his mother, Hannah, matching ages. Hannah Cook was listed with Henry’s name under hers. Maybe Hannah had been a cook on the Blocker estate. Hannah and Henry, rescued from oblivion.

Jimmy grew silent. His already deep-set blue eyes receded further under his brow as he scanned one of the photocopied lists. After a moment he said, “It’s hard to look at these. Just a name with a price after it, like ‘Sarah, 13, $900,’ or ‘John, blacksmith, $1,800,’ and ‘Elizabeth, 50, $400.’ And turn the page, now look at this one: ‘Sarah, very old, $5.’ Or how about this: ‘Sterling, 5 weeks, $100.”

List of enslaved people of Mimosa Hall plantation, Harrison County, Texas. Original text from a planter’s journal: “Inventory and Appraisement of the Property of the Estate of John Webster.”

He drew in his breath with a sniff: “And sometimes you’d see horses and cows and pigs on the same page. They just lumped people in with livestock and traded ’em. Slaves were livestock—property—and that’s kind of hard to comprehend.” He cleared his throat. Then, he said “oh,” as if he had remembered something. “I ran across a strange one here,” he said, “doing my Hilliard research.”

I knew that Jeremy Hilliard was Jimmy’s great-great-grandfather and that he’d been a well-off planter. Jimmy explained that Hilliard had a stepdaughter who married a man named James Sims.

“Now, look here,” he pulled another photocopy from a manila envelope. “James Sims owned a slave named Henry Sims.” He paused to make sure I was following. “James Sims. Henry Sims. Henry was James’s half-brother.” His bushy gray eyebrows rose, then he shrugged his shoulders and turned up his open palms.

“A person could own his brother.” He chuckled softly as though he didn’t know what else to do about this disturbing discovery but to make light of it.

I felt awkward too, and changed the subject to Della Love, but Jimmy told me he hadn’t run across any Loves yet.

I thanked both Jimmy and Edna for keeping the Historical Society Library—this rich resource—open. They promised to let me know if anything about the Loves showed up in their research.

I made a quick stop by Nuthel’s home to say goodbye. I found her outside collecting the mail, wearing a brown straw hat from her large collection. She invited me in for iced tea, but I knew that if I accepted, any chance for a timely departure to Dallas would be wiped out by Nuthel’s generous hospitality. Besides, I enjoyed visiting with her. I begged off and we stayed outside, catching up.

She was happy we’d made so much progress on Saturday. She asked me again if I’d liked the beans that she had picked from her own garden and cooked for the potluck. I told her I had, though I did not tell her that, in truth, I had been too taken up with Doris’s anger and my own to notice what I was eating that day.

“You know,” she said, “I am real happy that Coach, R.D., and Philip—and we’ll see who else—are going back out there in September with their tractors. Now that’s gonna be something, to finish it off from like it is.”

The September cleanup would be the first one to happen without me. That’s good, I thought. It’s healthy for the group to rotate the leadership, for someone else to take over. Yet I couldn’t help letting Doris’s words about not needing me color my feelings about the day. I said nothing to Nuthel about any of this, just gave her a long goodbye hug and resisted telling her I’d changed my mind and would come in for tea after all. I would miss her.

I backed out of her driveway and headed away. I could see Nuthel waving in my rearview mirror until the road curved, and then she was out of sight. The three-hour drive between Marshall and Dallas would be good. Three hours to begin to digest all that had happened in the last few days: the complexities of human relationships; the intricacies of slavery, with relatives “owning” each other and the mixed blood; the hidden history of land theft, and the land theft still going on.

Even a few minutes with Nuthel had been a balm. She lived with a kind of healthy distance from the world, in a place that was informed by the perspectives of age, education, and travel. Above all, she was, as she’d said many times, a farmer. She was grounded in the land itself.

That deep connection to the land was shared by almost all the people who had been drawn into the communal effort at Love. I was convinced of the connection between our treatment of the land and our relations with our fellow humans. The racial wound, so deep that it was making itself felt between Doris and me despite our best efforts, had its origins in the same worldview that had led to the cruel and thoughtless exploitation of the earth. It seemed no accident that East Texas, historically considered one of the most racist parts of the state, should also be home to one of the worst toxic “superfund” sites in the country, Longhorn Munitions.46

I did not want to be alone with these thoughts. I had one friend, besides Philip, who might share this bubbling stew of historical, environmental, sociological, and human concern. Born and raised in the area, my friend was one of the engineers brought in to analyze the hazardous materials at the Longhorn, the eight-thousand-acre “superfund” site adjoining Caddo Lake and its rare and fragile wetlands. Caddo Lake is also the community water supply for the area. My friend had explained how the plant manufactured rocket fuel during the Cold War, and then years later, when hitherto unknown toxins were discovered at the site, the scientists were called in. It turned out that the plant had also been charged with experimenting with explosives. In doing so, toxic compounds were created that never existed before or since. Detoxifying the most dangerous parts of this site was complicated beyond imagining. Nonetheless the site was being designated a National Wildlife Refuge.

I was able to stop and visit with my friend on my way back to Dallas. She was glad to hear from me and eager to hear the latest developments at Love Cemetery. I filled her in on the progress we’d made and how invaluable the generous sense of community of my cousin, Philip, whom she knew, had been.

I quickly got to the part about Doris and me. When I told her about Doris’s reaction to the releases I had asked people to sign, the first thing she said was, “Of course Doris would be upset by a white person coming in and saying ‘just sign here.’” Her father, who’d grown up in that area, had told her that during the Depression, one of the local storekeepers had offered people cash to “help them through the hard times.” The “store system” again. All they had to do was sign a piece of paper. At that time, out in the country many of the African American people he dealt with were illiterate and not by choice. The forces arrayed against their becoming literate were legion, including the infamous Jim Crow laws, which were a holdover from slavery. They didn’t understand the severe terms of the “loan” he gave them, described in papers they couldn’t read, and which they had to sign with Xs or else not be able to put in the season’s crops or feed and clothe their families. Many lost the deeds to their land. The storekeeper ended up being one of the biggest landowners in the area. “It caused a huge amount of bitterness among black folks,” she explained, “and deepened mistrust of whites.”

Though the storekeeper in her father’s story was infamous, I now understood all too well how pervasive was the practice of taking deeds to African Americans’ land in exchange for cash or flour, sugar, cloth, or seed. This was how the plantation system of bondage reasserted itself, how whites attempted to regain control over a black work force they could no longer call their own. Whether it was called “the store system” or was actually debt peonage, which is a crime, each time I encountered an iteration of this system, I developed a clearer sense of the deep, ingrown resistance to the very idea of black land ownership that was embedded in white history.

Now I began to understand that I had unwittingly stepped into an archetypal role. I had become the white-person-with-a-piece-of-paper for the black person to sign. If this was true, how could Doris not feel suspicious? Whatever had come between us was larger than the two of us, too large for us to be able to talk about. Even language itself was part of the problem, full of unconscious associations. Our interchange had taken place within a context in which African Americans had suffered devastating economic consequences anytime they signed the white man’s paper.

I drove into Dallas close to dusk. I wanted to get off the freeway as soon as possible. I needed to slow down. I needed to collect myself before walking into my mother’s for a late dinner. Though we had not yet spoken of what I was doing in much detail, my mother, Ruth, among all the family and friends I had in Dallas, seemed to grasp what I was trying to accomplish at Love Cemetery.

I turned off at Lemmon Avenue, an older, crosstown street that would take me to Turtle Creek, a graceful, curving street that followed the path of the creek. As I sat at a long red light at Lemmon, I realized that directly across the intersection, at the corner of Lemmon and Central, was the Dallas Freedman’s Cemetery. That’s where I needed to stop. I turned off when the light changed, parked my car, and got out.

The Dallas Freedman’s Cemetery and Memorial Park was a long way from the remoteness of Love Cemetery. The Freedman’s Cemetery is the largest reburial project to date in the United States, with 1,157 remains reinterred in 1994. The Freedman’s Cemetery project was even larger than the African Burial Ground Project in New York, which is now a National Monument.47

On either side of the marble entry arch were two larger than life-size dark cast bronze sculptures by David Newman. On the left was a powerful, calm, broad-shouldered African warrior holding a large sword with its tip to the ground between his feet, a cemetery guardian who looked directly at anyone approaching the entry. On the right side was a serene, regal woman, draped in a graceful robe, turbaned, and holding a lyre. This figure too gazed directly at me as I walked closer. Both had the faintest hint of a smile. The woman depicted was the “griote,” the keeper of communal memory. Both the warrior and the griote had an uncanny presence, a command of their worlds. The sculptures were simple and stunning. I peered through the iron bars of the locked entry gate between them and saw a walkway with an incised marble slab in the center. Off to the right was a well-tended grove of post oaks surrounded by recently cut grass. No one was in sight. The peacefulness of the place, the mystery, beckoned.

I walked the perimeter looking for another way in but could find nothing. Across the street was Greenwood Cemetery, one of the oldest in Dallas, and across from that, Calvary Cemetery. It was a quiet neighborhood of cemeteries on two sides and high-speed traffic on the other two. Why this park had been locked every time I had driven by on my way to and from East Texas was beyond me. I’d been wanting to see it from the inside for over a year. It was a well-kept place, inviting and clearly meant to be used.

After pacing back and forth, I finally found a way in that no one seemed to have noticed. I kept looking around, unable to understand why this memorial was locked up when all the surrounding cemeteries had their gates open. They had elaborate marble carvings and headstones, carefully incised granite markers, tiny streets within name “Hope,” and “Faith,” whereas the Freedmen’s Memorial had no individual markers, only a quiet grove of oak trees. Still, there was no one around, only speeding cars and the dead. I slipped in and quickly found myself standing on the site of Freedman’s Town, once a remarkably vibrant, self-sustaining black community.

A vagrancy ordinance passed in 1865 in Dallas on the heels of Emancipation imposed fines and a six-month prison term on blacks for walking on Dallas streets. This draconian legislation directed against African Americans, along with other discriminatory conditions that persisted well into the twentieth century—prohibitions against black participation in civic life, lack of schools, churches, medical care, housing, transportation, jobs, economic opportunities, banks, public bathrooms, social clubs, swimming pools, athletics, and voting rights, to begin with—led to the growth of Freedman’s Town, which, in those early days, stood outside the Dallas city limits. It had been established just after Emancipation as African Americans tried to reconnect with family and find employment.

During its heyday, which seems to have lasted into the 1930s and 1940s, Freedman’s Town housed four black churches, which had each started grade schools and a high school. The Dallas Express, the African American community newspaper, was established in 1892. There were women’s associations—the Ladies Reading Circle was started in 1891, to mention one of dozens. The first local black Masonic Lodge was organized in 1876 in Freedman’s Town. There was a center for music and concerts where local black jazz and blues musicians like Blind Lemmon Jefferson and bands from New Orleans often stopped to play on their tours of the country. There was a swimming pool, a YWCA, and a branch of the public library. Freedman’s Town had its own medical clinics staffed by black doctors, dentists, and nurses, its own funeral home, bank, insurance companies, art clubs, movie theater, and cemetery. Freedman’s Town became the center of black intellectual, social, educational, religious, and cultural life for a good part of the city.

As Dallas grew, it lost the name Freedman’s Town; the area became North Dallas and was incorporated into the city. Burials in the Freedman’s Cemetery reportedly continued into the 1920s, when the City of Dallas Sanitation Department forced its closure, supposedly because of overcrowding, a claim later proven to be false. The cemetery itself, where I sat that evening, was turned into a park for children.

Part of the cemetery was desecrated and paved over in the 1940s. The city bulldozed the tombstones, ground them up for road fill for the big freeway, and opened Central Expressway with enormous fanfare in 1949—a shining example of civic growth and progress.

Finally, in the 1980s, when the city wanted to widen Central Expressway again, the African American community of Dallas, especially Dr. Robert Prince, a physician in Dallas who had family buried there, and Black Dallas Remembers, under the leadership of educator Mamie McKnight, organized and joined forces with the city preservationists. The City of Dallas, the Texas Department of Transportation, Black Dallas Remembers, the Dallas Historical Commission, the African American Museum of Dallas, and hundreds of volunteers arrived at a compromise: the creation of the Freedman’s Cemetery and Memorial Park, in which I sat that night. It took twelve years to negotiate, design, and create the memorial. More land was added to the cemetery to replace what the city had taken and would need for the expansion. Then more than 1,100 burials were reinterred. The city agreed to permanent maintenance of the memorial. The book Facing the Rising Sun: Freedman’s Cemetery was published and a documentary made for national television.48 A solemn celebration took place for the opening,

From inside the memorial I could see the figures that had drawn me in. The warrior and griote that guarded the cemetery on the outside appeared again, but inside the memorial they are in chains. Stripped of their power—the sword and the lyre—stripped of their clothing but for the barest covering, they were caught by the sculptor in the moment when they had been thrown off their feet and chained in the hold of a slave ship. Overpowered, broken, and crushed, they lay on either side of the entry arch, on the opposite side of the wall from their former, powerful selves. The warrior now had heavy chains on his left arm, which was thrown back over his eyes. His face turned away from the gaze of the onlooker. The woman, bareheaded now, held her face in her manacled hands. She covered her breasts with her crossed arms. They were frozen forever in this ship’s hold, making their way on the hellish Middle Passage from Africa across the Atlantic.

We will never know the exact numbers of Africans kidnapped from their homelands by Muslim traders and warring African tribes. Europeans joined in and fueled the plunder, escalating the number well into the millions. Roughly 20 million people were kidnapped, “disappeared,” and an estimated half of those captives, in wooden collars and chains, died on the forced march from the interior of Africa to the coasts. Those who survived were sold to the highest bidder and put aboard ship. Of the more than 11 million sold on the African coast, 9 million survived the horrors of the passage.49

The degradation and helplessness of being enslaved was captured more eloquently in each statue’s gesture than in the thousands of pages I’ve read on the history of slavery. I stood in front of first one bronze sculpture, then the other, taking in the images for a long time. I marveled at this simple and magnificently understated memorial to the suffering of America’s African ancestors who arrived here in chains. The cruelty of the Middle Passage is emblematic of the brutal history of slavery.

One slave ship captain candidly noted in his journal: “Women were taken aboard trembling and terrified. The prey is divided up on the spot…. Resistance or refusal [to be raped] would be utterly in vain.” Once sold, slaves were branded on board with the initials of the ship’s owners. Death ravaged the holds below deck before the ships even got started. The author of the hymn “Amazing Grace,” John Newton, for many years the captain of a slaving ship, mentions sixty-two people out of two hundred captives dying before his ship could leave shore. Deaths were so common that reportedly sharks circled the ships at anchor, then followed them out to sea. The voyage lasted months, and death dogged them at every turn. Captives rebelled: there were three hundred known uprisings shipboard and countless numbers never recorded. If freed from their shackles, some people jumped overboard rather than remain enslaved. Others refused to eat. Captains and crews administered lashes, they used thumbscrews, they used a metal instrument to force feedings. People rebelled in every way they could. One ship was commandeered by a group of enslaved women, who were able to turn the boat around to Africa but were unable to sail it back by themselves.

We know from the rare journals of former slaves, like Olaudah Equiano, that life in the ship’s hold was pure hell. The stench below deck—the combined odors of sweat, urine, feces, and vomit—was suffocating, he reported from firsthand experience. There was little room to move or turn over amid the hundreds of slaves crammed into the holds. The cries of the sick, the groaning, and the calls of the dying gave rise to the moans still heard in African American spirituals.

As I sat in front of these two sculptures, I wondered if it was even possible to imagine the terror of the Middle Passage. Of course I could not, and yet these sculptures gave the unimaginable a face, a sorrow, and a vulnerability so human that they invited me to try. I’d been drawn in by their beauty and power on the outside. Could I now take in their sorrow, their defeat, their cries? If I had any hope of understanding what had happened to my friendship with Doris, I had to try. There was so much pain between us, at least on my side.

I imagined. I imagined that I was living in a village in Africa, that I was out working in a field. There are other women in the field too. I don’t know how it happened, but suddenly I am being ripped from the pulsing center of my own life by thick, rough hands; ripped out of my mother’s, husband’s, children’s, father’s, sister’s, brother’s, lover’s arms; ripped away and bound, wrist to ankle, forced to march away from everything I’ve ever known—my native tongue, the shape of my lips as I spoke it, the place in my throat it comes from, the familiar smell of the land after rain, the color of the winter light, the way light beats down in summer, the shapes of the harvest, the smell of my land’s wood burning, the shape of the flowers, their smells, their color, the sounds, the tinkle of bells, young children laughing, a wedding song. Little to cover myself with but scraps I’ve held on to.

Where would I be today, or where would my family be, if 150 years or so ago, only five or six generations back, one of my ancestors had been the one captured and enslaved?

I tried to imagine being crammed into a crowded room with strangers, with no one who speaks my language, waiting, waiting, fighting for scraps, dying for water. For the first time in my life, I am in a place where no one knows my name or the names of my ancestors or the names of my gods. And I begin to forget all these things myself.

Forced to eat strange food that makes me sick, nothing of my home remains except the memories I cling to—that is all I have left, memory, but even my memory is torn, gnawed by the curse of hunger and burning thirst. I stand in my own filth. Soon I will lie in it.

Those hands that stole me now chain me to the floor of the ship’s hold. The boat is rocking, rocking me, like my grandmother used to do, but where are her arms? The stench, the wailing, the cacophony of cries—suddenly the person next to me gasps and screams close to my ear. Then she is silent. She has died. The hatch closes. They take away the light. There is barely any air. Consciousness, once a gift, is now the cruelest burden of all. I want nothing so much as to die, but we sail on like this. We speak different languages, yet our moans translate our differences into song. We barely live through this hell. Many don’t and are thrown overboard, sometimes dead, sometimes alive. I live.

After this I am put up on the auction block and sold to my “owner.” Then there is the journey that follows. I am in chains, whether they show or not. I learn to sing into the cracks, into holes in the ground, into wash pots. I learn to keep my being a secret in order to stay alive.50

As I sat in the Dallas memorial at dusk and allowed myself to imagine the life depicted in these bronzes, I began to understand the complexity of this history, its agony, and the devastation of being stripped of family, language, religion, even one’s name. I began to understand that healing my relationship with Doris wasn’t simple or easy, not at the depth I knew was required. I would have to earn my part of it. In order to even dream that our work at Love Cemetery could succeed, I had to be willing to sit inside the pain of Doris’s reaction to my behavior. The fact that much of it was unconscious on my part didn’t matter. Something very deep had surfaced. A shadow had fallen across my relationship with Doris. Was it my own racism? Did I assume that good intentions could override my unconscious actions, like the way I documented everything, photographed it, videoed, took notes, and recorded it? Some of this desire came out of the sheer excitement of being entrusted with this story and recognizing its depth. Some of my documenting came out of my own shyness and insecurity, my need to learn experientially, and my need to mask my discomfort first of all from myself.

Was my documentary instinct my craft, or was it my way of avoiding being present? Was it my way of defending myself? I knew what it was like to have people deny my experience. Was I documenting events, or was I buttressing my experience of them in order to control the narrative? I was getting a look at my unconscious white presumption about the white way being “the way things are done.” Looking for records in the Harrison County Courthouse had shown me how white people made the rules, kept the records, and wrote the history. There was power in being someone who knew how to use that system. I could see that. Now I was beginning to see the lens of whiteness that I was wearing, beginning to feel the glasses on my own nose, becoming aware of this distortion. I had a long way to go, and I had Doris to thank for piercing the shell of my whiteness, forcing me to see it more.

I sat there alone in the early evening light, still stunned by the breach with Doris, the Scottsville story of land theft my friend told me, and the awareness that driving on Central Expressway meant driving over ground-up tombstones from the Freedman’s Cemetery. I sat there, haunted by the knowledge of the community that had once lived, thrived, cared for their dead here, as once the community around Love Cemetery had. The community at Love had arisen out of the same hard times as the Dallas Freedman’s Town and had been able to claim the land and work it and prosper, for a time. I knew that I would not be able to write this story if I remained untouched. I had to learn these lessons, no matter how much they hurt. And I had to see that even having my feelings hurt came out of the privilege of being white. I could let this pain take over or I could say thank you for this lesson and be willing to sit and let it drive me deeper, let it broaden me to include more of what I’d been taught was other. It was teaching me that the other was also myself and that we are not separate.

And I knew that whether Doris still felt that I was needed or not, I needed to see this situation through. I may not have known why, but some instinct told me that the real story unfolding around Love Cemetery demanded that I—a white woman—and Doris, an African American woman, find a way through this together.