Men of the machine gun section of the 11th Hussars in the trenches at Zillebeke in the winter of 1914-15. Several of the men wear woollen caps, and one maintains one of the weapons. The trench, which lacks revetment, has been cut through tree roots, and at least one tree has been felled to help create improvised overhead cover. From the collection of Major General T. T. Pitman. (IWM Q51194)

By 1914 Western Europe had been at peace for more than four decades. Otto von Bismarck’s unification of Germany had culminated in the declaration of the German Empire in 1871. There followed a period of equilibrium in which the Drei Kaiser Bund, or ‘Three Emperors’ League’, helped hold peace in central Europe; Britain looked outwards to her world empire; and France, though stung by defeat in 1870, lacked power to challenge her new neighbour. Arguably tranquillity began to unravel from 1888 with the accession of Kaiser Wilhelm II, who was famously said to have ‘dropped the pilot’ when he dismissed Bismarck two years later. Thereafter France moved closer to Russia, whilst German fleet building, plus support of the Boers during the South African War, slowly pushed apart hitherto friendly Anglo-German relations, and a series of conflicts in the Balkans gradually destabilized Austria-Hungary. In theory the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in June 1914 need not have started a war – and certainly not a World War – but in the event it was the spark that lit the fuse that blew Europe apart. Though the immediate causus belli lay in south-eastern Europe, and Germany’s stated objective was support of Austria, existing alliances and war plans pointed to the West. The Kaiser was said to have been shocked to discover the impracticality of attacking in the East when military plans were based on a preemptive knockout blow to France, firmly framed as the most serious threat. So it was that seven out of eight German armies now swung westwards according to the diktats of a modified ‘Schlieffen Plan’, the German overall strategic plan for war. In doing so they quickly violated Belgian neutrality, an act that proved the final straw for Britain, which was now facing not only the possible defeat of France, but occupation of the Channel coast by a hostile power.

Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859-1941). Seen underneath the portrait is part of the text of a declaration made at his headquarters at Koblenz in August 1914: ‘I recognise no parties, but only Germans’, an attempt to unify the nation behind the war effort. (Author’s collection)

European armies of 1914 differed in the detail of their weapons, equipment, uniforms and organizations, but a strong common thread ran through their purpose and tactics. Rising populations, increasing wealth, industrialization and conscription in Continental powers had made massive armies possible. Increased tensions and new army laws in France and Germany had made sure that they continued to grow – potentially to millions in case of war. The universal expectation was that such a war could not be won without movement and attack, and recent historical precedent suggested that the struggle would be both short and decisive. The idea that it would be ‘over by Christmas’ was by no means as gauche as it now seems. The Austro-Prussian war of 1866 was famously a ‘seven weeks’ war; France had lasted about six months against Prussia in 1870. The relatively lengthy American Civil War and Boer War were not regarded as reliable indicators of what might happen in Europe. As Captain E. G. Hopkinson of the East Lancashire Regiment put it, ‘Few, indeed, thought that the war would last long enough to interfere with the cup final of April, 1915.’1

No recent European war had been won by defence. Prussia had defeated its enemies by swift wars of manoeuvre, and Staff colleges still taught the maxims of Napoleon and Clausewitz – in which passivity was tantamount to surrender. With some justification initiative was thought to lie with the offence: for only by advance and attack could one concentrate force against an inferior portion of the enemy and inflict decisive results. For the French in particular attack had assumed an almost mystic quality: a belief persisted that the Franco-Prussian War had been lost partly due to lack of élan, and the possibility that the enemy might muster superior numbers seemed to suggest that rapid advance and massed force was the route to military salvation. Whilst there had been numerous technical advances, the most important ‘arms of service’ were the same in 1914 as they had been a century earlier: infantry, cavalry and artillery.

The artillery was commonly divided into ‘field’ units which accompanied the fighting troops on the battlefield, and heavier guns, the main purpose of which was to batter fortifications or other fixed positions. The field elements were by far the most numerous. On the British ‘War Establishment’, for example, an infantry division also contained four artillery brigades, three of 18-pdr field guns and one of howitzers, totalling 72 guns. The field piece by which others were judged was the vaunted 1897 model French 75mm. At the time of its introduction this was the ‘Quick Firer’ par excellence. It was equipped with a hydro-pneumatic recoil system, a fast-acting breech mechanism based on a screw, a crew shield and an automatic fuse setter. The ammunition was ‘fixed’, meaning that rounds came complete in a single unit, with the shell seated in its cartridge case containing the propellant. All the loader had to do was slide the round into the open breech in a single movement. The ‘75’ was mobile by previous standards, had a maximum range of about 4 miles, and for short periods could average more than a dozen rounds a minute. Firing air-bursting shrapnel it was in its element breaking up concentrations of attacking troops. The individual gun section comprised six gunners, six drivers and a corporal, with limber and ammunition wagon, commanded by a sergeant. Over 1,000 four-gun batteries of 75s existed at the outbreak of war, and more than 17,000 pieces were manufactured by 1918. Tactically the field artillery was usually deployed in close support, often firing at relatively close, directly observed targets. The French batterie de tir did not usually begin shrapnel fire until within 4,400 yards.

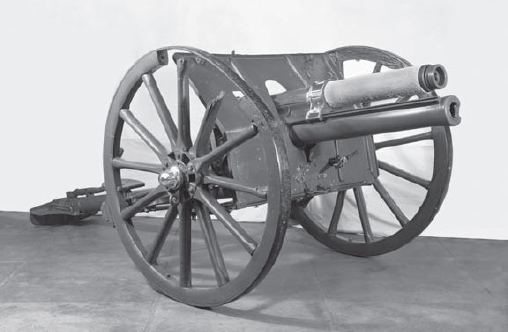

One of the 13-pdr guns used by ‘L’ Battery, Royal Horse Artillery, at Néry, during the retreat from Mons, September 1914. Under machine gun, rifle and artillery fire, the battery fought until its ammunition was exhausted. Three won the Victoria Cross: Captain E. K. Bradbury, who continued to direct the guns despite the loss of a leg, and is now buried in Néry Community Cemetery; Battery Sergeant Major G. T. Dorrell, who took over after all the officers were killed or wounded; and Sergeant D. Nelson, who remained at his post though seriously injured. The gun is now displayed in the Imperial War Museum North, Manchester. (IWM Q68293)

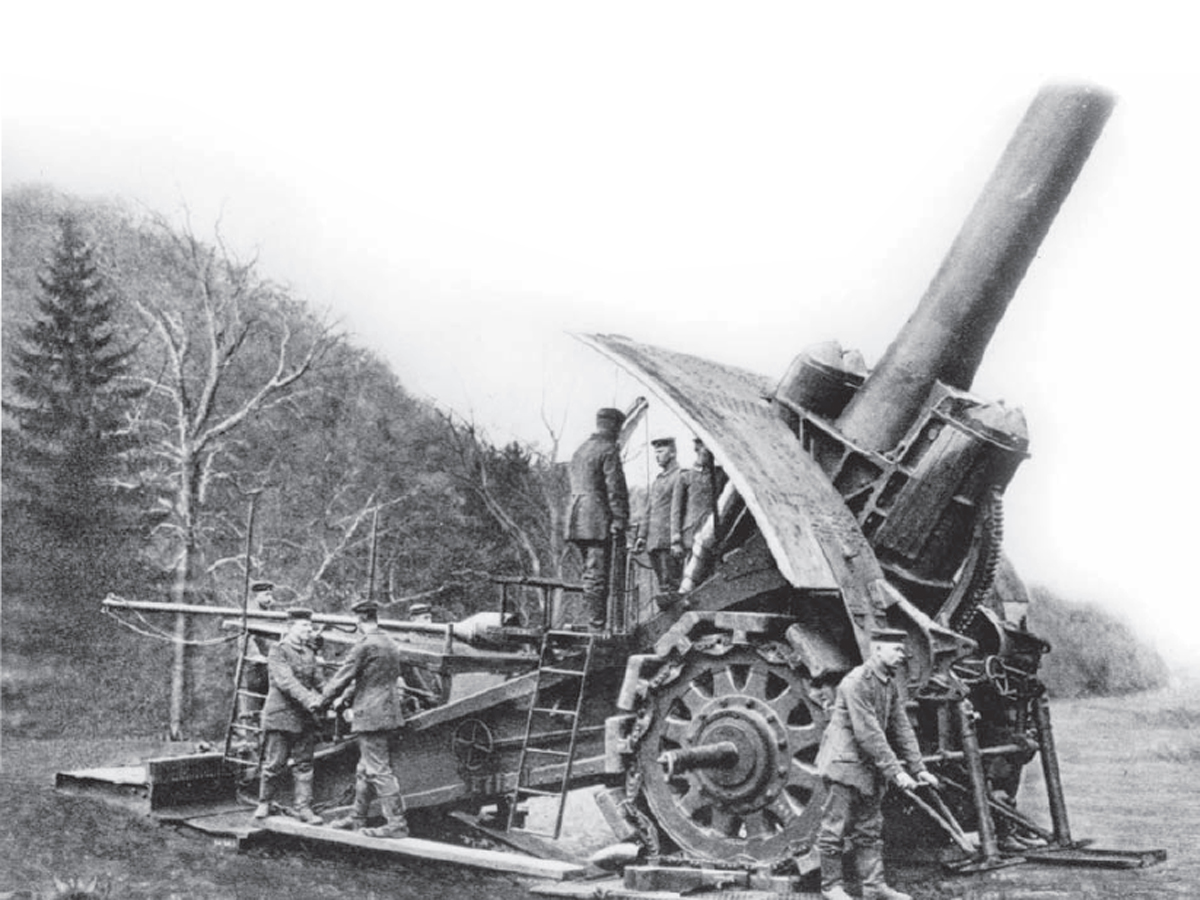

By common consent the Germans were best equipped with heavy artillery. By 1913 the ‘Foot’ artillery disposed 24 regiments, organized into 48 battalions, each of four batteries of heavy guns, or two of 21cm Mörser. Approximately half of the howitzers were 15cm types, the latest model of which was capable of throwing shells over 9,000 yards. At the super heavy end of the spectrum were a relatively small number of massive fortress-busting mortars. The biggest of all was the 42cm, whose shell stood taller than its crew. A smaller 30.5cm Austrian model was also on the inventory, and it was these weapons, together with the 21cm, which were destined for the smashing of the Belgian forts that threatened to impede the speed of the German advance. Firing the bigger guns was no light matter, as US Corporal Amos Wilder explained:

With the shells came also bags of powder and fuses. When a gun was fired one member of the crew adjusted the barrel for the required direction and trajectory; another rammed home the shell after screwing on its fuse; another added the powder charge (a bag not actually of powder but of thin yellow strips); a fourth closed the breech block; then all seven of the gun crew put their fingers in their ears as the last, at the officer’s command, pulled the lanyard.2

The range of such weapons was remarkable. The German 15cm howitzer could fire anything from 3–6 miles depending on the model and type of shell; the mighty 42cm mortar could lob approximately 8 miles. Some of the naval guns eventually deployed on land would comfortably double even this distance.

French uniforms of 1914, in the Historial de la Grande Guerre, Péronne. Left to right: cuirassier, with distinctive breastplate; infantry, with greatcoat and pack; and officer. The famous red trousers would disappear in 1915 with the adoption of an ‘horizon blue’ uniform. (Author’s collection)

In many early engagements of the war the artillery would fight at comparatively close ranges, often firing over ‘open sights’ against targets observed from the gun line. Once fronts became fixed this would change quite rapidly with the use of ‘forward observers’ who positioned their observation posts amongst, or even slightly forward of, the main infantry positions. Map or ‘predicted’ fire similarly became more important as the war progressed. Artillery would take a significant toll in the ‘battles of the Frontiers’, but if anything its position as killer-in-chief would become more obvious later. Overall artillery was easily the most deadly weapon of World War I, far outstripping even that reviled newcomer, the machine gun. According to a sample of 212,659 wound cases examined at British casualty clearing stations, over 58 per cent of wounds were caused by shells and trench mortar bombs; 39 per cent by bullets from rifles and machine guns combined; 2 per cent by grenades, and less than one-third of a per cent by bayonets. Tables considered by the Munitions Design Committee in 1916 showed shell and mortar wounds outnumbering all others by more than two to one. Figures cited by Winteringham and Blashford-Snell suggest that in the period 1914–15 about 50 per cent of German casualties were caused by artillery, rising to a staggering 85 per cent from 1916 to 1918. Aggregating these statistics brings us to the conclusion that two-thirds of all deaths and wounds on the Western Front having been caused by artillery is very close to the mark.

Belgian troops on the march, 1914. Resistance helped upset the Schlieffen Plan, and assisting ‘Brave Little Belgium’ was one of the major factors bringing Britain into the war. Belgium had bought its first Maxim guns as early as 1909, and seen here are the 1912 model machine gun carts drawn by dogs. (IWM Q81728)

The impact of shells, which tended to get bigger, more frequent and more impressive in their performance as the war progressed was quite literally stunning. Captain McKinnell of the Liverpool Scottish described the largest varieties as passing ‘like an express train’ even if aimed at a distant target. As C. E. Carrington of the Royal Warwickshires related, old soldiers learned to recognize a shell by its sound: some whistled, others shrieked. The smallest projectiles leaving field guns in the distance might sound like ‘champagne corks’. The wounds and deaths caused by shells involved the most shocking sort of disfigurement and dismemberment. As Frederic Manning of the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry observed, though all the dead were equally dead, ‘it is infinitely more horrible and revolting to see a man shattered and eviscerated, than to see him shot’.3 Gustav Ebelshauser, 17th Bavarian Infantry, was witness to just one tragedy amongst thousands:

Aldrich had been struck by a large steel splinter that had made a clean cut through flesh and bones slightly beneath the belt, slicing his body in almost two equal halves. A strip of cloth at the back of his uniform prevented the two pieces from falling apart. Instead it had caused them to open, fully exposing to view their ghastly contents. The splinter hit with such force that Aldrich’s head had been forced between his legs. But his face looked as though it were still alive…4

Many memoirs include incidents in which bodies are so shredded to odd fragments that they have to be scraped up into sandbags for burial. Seaforth Highlander Norman Collins was appalled to see how much of a man’s intestines could be blown out, whilst the victim yet remained alive. There were also bizarre wounds, such as that of the German officer seen by Australian E. P. F. Lynch, who was relatively healthy bar a neat slicing off of his top lip.

A French 75mm gun and limber in the museum at Fleury, Verdun. Gunner Paul Lintier described firing this piece: ‘The gun springs back like a frightened beast. A tongue of flame leaps from the muzzle. Your skull vibrates, a thousand bells ring and peal in your ears, you shake from head to foot. The blast from the explosion has raised a cloud of dust. The ground trembles. You have a taste in your mouth that is insipid to begin with, then bitter: the taste – or is it almost more like a sensation – of powder.’ (Author’s collection)

A cabinet type hand-coloured studio portrait of a Prussian guardsman, Potsdam, c.1913. The Haarbusch, or falling plume, was a parade item not usually worn in other orders of dress, its holder then being replaced with the spike. (Author’s collection)

Some had the narrowest of escapes. Artillery officer N. F. Tytler remembered taking cover as a round hit nearby:

As soon as the shell had burst I looked out just in time to see a red lump rising out of a red pool… I pulled him into one of the trench dugouts and started a party to clean him up and then report damages. Extraordinary as it appeared, he was perfectly untouched… The shell must have burst on the back of one of the horses, as there was no crater in the ground.5

Blasts could quite literally throw men around, though it did not always kill them. As Unteroffizier Hundt remembered:

The shells came over in great salvoes, exploding with ear-splitting detonations. Then bits were flying in all directions: clods of earth, stones, pieces of wood and showers of loose earth which came down everywhere like rain … there was an almighty explosion right next to me, which seemed to get me right in the stomach and innards. I was seized by its irresistible violence and flung into the air. When I came round I had been thrown 3 metres into a hole and covered with a light layer of earth. I jumped to my feet and saw a huge shell crater right next to me. A man of my section, who had been shot through both legs, was being carried off. Despite the most energetic efforts, no trace was found of three of my men…6

Perhaps surprisingly the most remarkable statistic about shells was that a majority of those fired actually killed nobody. From March to November 1918 alone British forces on the Western Front expended more than a million shells each week, and sometimes two or even three. This was more than half a dozen for every single German under arms, even allowing for a generous margin of ‘duds’. Conversely, unlucky strikes on bunched or vulnerable targets could prove catastrophic. Mortar crewman Stuart Chapman reported a hit on a crowded estaminet in Arras that killed 28; on another occasion he was witness to a German 15cm shell that hit a house and killed not just 12 soldiers, but seven civilians, and a further four troops were wounded. Most could recall some such disaster.

Yet the significance of the artillery was not in any one round, but the marshalling of bombardments to multiply effect and even deny whole areas to an enemy. During one bombardment at Delville Wood in 1916 it was calculated that 400 German shells per minute were raining down on the South African positions. Private Charles Dunn returned to the wood after such a pounding:

Dead men were lying all about. At some parts one was obliged to step over the dead bodies of Germans, Britishers [sic], South Africans and Highlanders. And some awful sights there were. Some men with half bodies, heads off, some were in a really awful state. All the time that I spent in Delville Wood in one large shell hole a dead Jock was sitting upright, he had evidently died from loss of blood. On his left lay half a man – he was a Jock too. All that could be seen of him was his kilt and two legs.7

Little wonder that bombardment became one of the greatest trials of the soldier; fear and exhaustion, combined with brain-shaking concussion, would lead ultimately to the as yet little understood condition of ‘shell shock’. This ailment was not named until February 1915 when the term was coined by Dr C. S. Myers writing in the Lancet. Yet, interestingly, few could actually agree what shell shock was. Sufferers seldom felt their real problem was understood while the authorities believed that ‘shell shock’ was a cover for cowardice and malingering. Both sides could point to specific instances to support their views. The treatment, if any, varied radically depending on circumstance and the experience of the medical staff involved. Some victims of nervous breakdown were treated simply as disciplinary cases, others as lunatics, and at the most extreme end of the spectrum were given a primitive form of electric shock therapy, which, it was observed, was useful at least in the sense that it sometimes exposed those who had been shamming their neurosis. Some were handled much more sympathetically and rested behind the line. Perhaps the biggest surprise was that there were not more shell shock casualties: in 1915 for example there were just over 20,000 cases of ‘nervous disorders’ of all types requiring medical intervention. This total amounted to less than 4 per cent of all British hospital cases, and covered things that were not actually ‘shell shock’.

Not until the institution of a War Office Committee of Enquiry in 1922 was the issue systematically examined. Then there was broad agreement that the phrase ‘shell shock’ was not really useful, Dr W. H. Rivers being just one of many medical practitioners who pointed out that stress was the main factor in most cases, ‘shock’ being merely the last straw. Some were physical victims of concussion to brain and spine; many more simply collapsed under the strain of combat; some presented complex mixtures of the physical and emotional. Major General H. S. Jeudwine, former commander of 55th Division, iterated the opinion that shell shock had been used as a portmanteau term to cover everything from the ‘badly frightened’ to those suffering serious derangement of nerves or health. Its incidence happened to have been greatest in the middle of the war when the armies were static under fire. Historian John Fortescue offered the surprisingly modern conclusion that stress was cumulative and everybody had his limit where combat was concerned, as ‘even the bravest man cannot endure to be under fire for more than a certain number of consecutive days’.8

The cavalry were no longer the decisive fighting force they had been in the Napoleonic era. Nevertheless they retained a significant, though reduced, niche in the order of battle. Horsemen could move faster than infantry, at least for short periods, and could screen army movements as well as probe enemy positions. They could also act as ‘mounted infantry’ and defend outposts, act as a spoiling or surprise force, or could exploit gaps or enemy retreats. Likewise they could seize important positions until the main body came up to secure them. The old distinctions between ‘heavy’ and ‘light’ cavalry, and ‘dragoons’ had become increasingly blurred: indeed German cavalry were now issued with lances whatever their theoretical designation. In the French mounted arm all had lances except the heavy Cuirassiers. Perhaps surprisingly the cavalry also retained swords as well as a carbine or rifle. Even after the first clash of arms British instructions issued as part of Notes From the Front stated that cavalry patrols should ‘invariably carry their swords – not their rifles – in their hands for immediate use’. The official default action on meeting enemy cavalry, even if superior in numbers, was to ‘charge at once at the gallop’.

Men of the 16th Queen’s Lancers on the retreat from Mons, September 1914. The 16th were part of 3rd Cavalry Brigade, and engaged as early as 22 August when they gave chase to an enemy patrol, and then overran a party of Jäger. During the retreat they attempted to screen the crossing of the Crozeat canal, but were driven out of Jussy on 29 August. On 12 September they succeeded in ambushing the 13th Landwehr Infantry Regiment, killing or capturing almost a complete company. (IWM Q56309)

The basic mounted unit was the regiment, divided into squadrons. In 1914 cavalry were sometimes deployed in complete brigades, but were also attached in smaller units to infantry divisions. In the German order of battle a cavalry regiment formed part of each division; in the British, a squadron. The French cavalry were widely acknowledged as amongst the best, animated with ‘patriotic spirit’ and having good march discipline and well-informed officers. A British report of 1912 stated that French horse could manage a steady 8 miles per hour, and that in a patrol action it was possible for small groups of half a dozen to cover anything up to 45 miles in a morning. Perhaps less sensibly they displayed ‘contempt’ for rifle fire, and were not inclined to admit that they required infantry support.

Vorwärts – ‘Forwards’ – a German patriotic postcard of 1914 showing an infantry standard bearer on the advance. Too often dug-in troops brought such popular heroics to a premature halt. (Author’s collection)

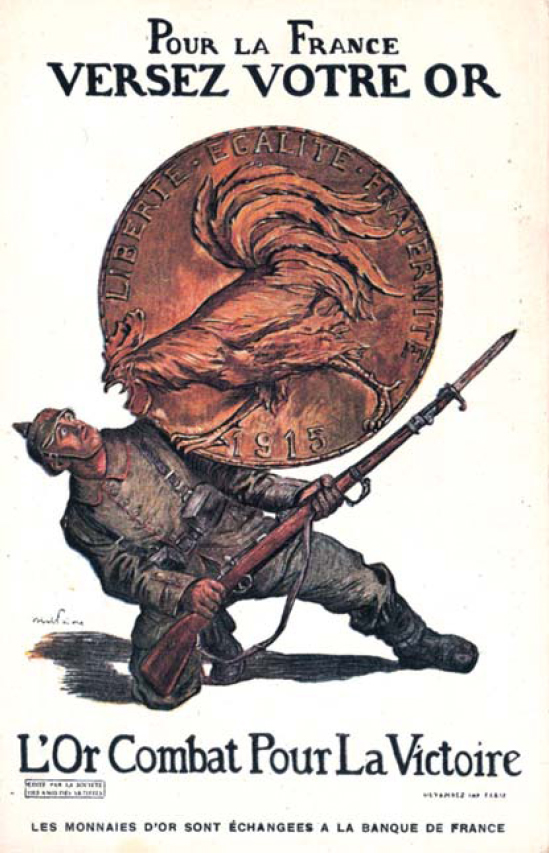

A French poster by Jules Abel Faivre – ‘Give your gold for France: gold fights for victory’. The German infantryman is confronted by an angry French cockerel and crushed by the weight of money. (Author’s collection)

Infantry were by far the most numerous of the fighting troops, and also took the vast majority of the punishment. Not only did German drill manuals warn the foot soldier this was so, but British statistics proved it. According to that great digest The Military Effort of the British Empire, no less than 86 per cent of all casualties fell on the infantry. Captain Henry Dundas of the Scots Guards did not survive the war, and so was without benefit of hindsight when he wrote:

The infantry in the line, who bear the brunt of the whole thing, get nothing done for them, get paid a pittance compared to anyone else, and then get butchered in droves when the fine weather comes. No one would object to being condamnés à la mort as the French pithily describe the infantry, if there was a little fattening up attached to it.9

The infantry were universally armed with bolt action rifles. In the four decades leading up to 1914 the ‘infantryman’s friend’ had changed almost out of recognition. The rifle was no longer a single-shot large-bored beast, but a relatively slender, relatively high velocity, precision tool with a magazine. These improvements had been made possible by the perfected, powerful, smokeless powder, brass cartridge – now usually with a pointed jacketed bullet – which was easy to handle, and worked reliably though the loading mechanism. The penetration of such a bullet is astounding to anyone who has not seen it first hand. At 200 yards a .303 round will cut through a house brick. According to British training anything under 600 yards was close range, and most rifles were sighted up to about 2,000 yards. In 1915 Corporal W. F. Lowe of the 10th Durhams reported an incident in a crowded trench in which one man – being wounded in the act of reloading – suffered an accidental discharge. His bullet went straight through his neighbour’s head and ricocheted through the arm and thigh of a second man, before landing in the stomach of a third.10 What happened when a man was hit varied considerably and depended greatly on where he was struck and at what range. Canadian Herbert McBride explained some of the possibilities:

At short ranges, due to the high velocity, it does have an explosive effect and … when it strikes, it sounds like an explosion. Bullets may be cracking viciously all around you, when all of a sudden, you hear a ‘whop’ and the man alongside goes down. If it is daylight and you are looking that way, you may see a little tuft of cloth sticking out from his clothes. Wherever the bullet comes out, it carries a little of the clothing – but it is unmistakable… And the effect of the bullet, at short range, also suggests the idea of an explosion, especially if a large bone is struck.11

Modern experimental techniques show that where any significant body mass is hit by a fast-moving projectile a temporary cavity is formed, and often the bullet begins to tumble – massive tissue damage being the result. French soldier Marc Bloch saw a comrade’s skull quite literally shattered by a bullet that left half the face hanging, ‘like a shutter whose hinges no longer held’.12 Rifleman John Asprey of the 1st Royal Irish Rifles was killed by a ricochet that ‘turned at right angles’ – and hit him in the left temple. Usually entry wounds were deceptively small and neat: as Private R. G. Bultitude of the Artist’s Rifles put it, ‘bullets drill a fairly clean hole’.13 Exit wounds, on the other hand, were often ugly and gaping. When Siegfried Sassoon took a sniper’s bullet and slumped against the side of a sap his initial impression was that a bomb had hit him from behind. Stomach wounds were nasty, and often fatal – slowly. Lieutenant D. W. J. Cuddeford of the 12th Highland Light Infantry saw one such at Arras in 1917:

He was only a boy, obviously not more than about 17 years of age, but he had always refused to be sent back to the Base Depot along with the other ‘under ages’. The bullet struck him in the belly, and as is usual with one of these abdominal wounds he rolled about clawing the ground, screaming and making a terrible fuss. Certainly, to have one’s guts stirred up by a red hot bullet must be a dreadful thing, and that a bullet is really hot after its flight through the air is well known to anyone who tries to pick up a newly spent one. However, they got the boy back into the trench, opened his clothes and put a bandage around his middle over the wound, but of course we could see from the first it was hopeless.14

Conversely there were some men, hit in non-vital areas, who had lucky escapes when a round passed clean through without inflicting serious injury. McBride similarly described a long-range, and probably low-velocity, impact where a bullet slipped into a soldier’s leg and the man remained unaware for sometime that his minor injury had been caused by a bullet.

Bayonets were taken seriously by military authorities, and drill with ‘cold steel’ featured prominently in training. Generally it was assumed that the longer the bayonet, the better ‘reach’ its user would have in a fight. The bayonet charge was the final phase of the attack, intended, as British instructions put it, to give ‘moral and physical advantages’ over a stationary line. Though useful in the dark, or for the intimidation of an unwilling prisoner, few bayonet wounds were actually inflicted. Nevertheless soldiers found other applications for them and strict injunctions had to be issued against using them as pokers or toasting forks. Jean Norton Cru, French veteran of Verdun, was particularly scathing. He had never seen a bayonet used, stained with blood, nor stuck in a corpse. True bayonets were ‘fixed’ at the start of an attack, ‘but that was not a reason for calling it a bayonet charge, any more than a charge in puttees’.15

In the infantry the principal tactical units were the battalion, of about 1,000 men, and the company, four of which made up the battalion under German, British and French organizations. The infantry attack was similar in the doctrine of all the combatant nations. Battalions would advance on the enemy, starting off in columns of various types for ease of movement, fall into skirmish lines for maximum deployment of their weapons, then engage. Having gained the upper hand with fire they would charge forward, taking the fight to the enemy, perhaps with the addition of reserves thrown in at a vital moment. There were, however, differences in the detail. In the British synthesis, as outlined in the 1914 Manual of Infantry Training, the troops were divided into firing line, supports and ‘local reserves’. Ideally a portion of the force held the enemy by fire, and the crucial blow was struck by the general reserve. The attack would begin as a ‘determined and steady advance’, though the routes forward would be planned with an eye to concealment and opportunity for ‘covering fire’. The attackers were not to halt until ‘compelled to do so’, and fire was to be used with the object of making ‘advance to close quarters possible’. When checked by ‘heavy and accurate fire’ the infantry would resort to advances by rushes, using either the whole line, or parts, as the manual explains:

The fact that superiority of fire has been obtained will usually be first observed from the firing line; it will be known by the weakening of the enemy’s fire, and perhaps by the movement of individuals or groups of men from the enemy’s position towards the rear. The impulse for the assault must therefore often come from the firing line, and it is the duty of any commander in the firing line, who sees that the moment for the assault has arrived, to carry it out, and for all other commanders to co-operate.

Designed specifically with fortress destruction in mind, the 42cm mortar was the ace in the pack of German heavy artillery in 1914. Though designated ‘mortars’ in German terminology, these pieces were effectively super heavy howitzers – throwing monster 2,000lb shells more than 8 miles. Along with Skoda 30.5cm and 21cm ordnance this class of mortar was deployed against the forts of Liège, Namur, Antwerp and Maubeurge. Though many guns have been popularly dubbed ‘Big Bertha’ this was the original – being nicknamed after Bertha Krupp (1886-1957) of the Essen armaments dynasty. (IWM Q65817)

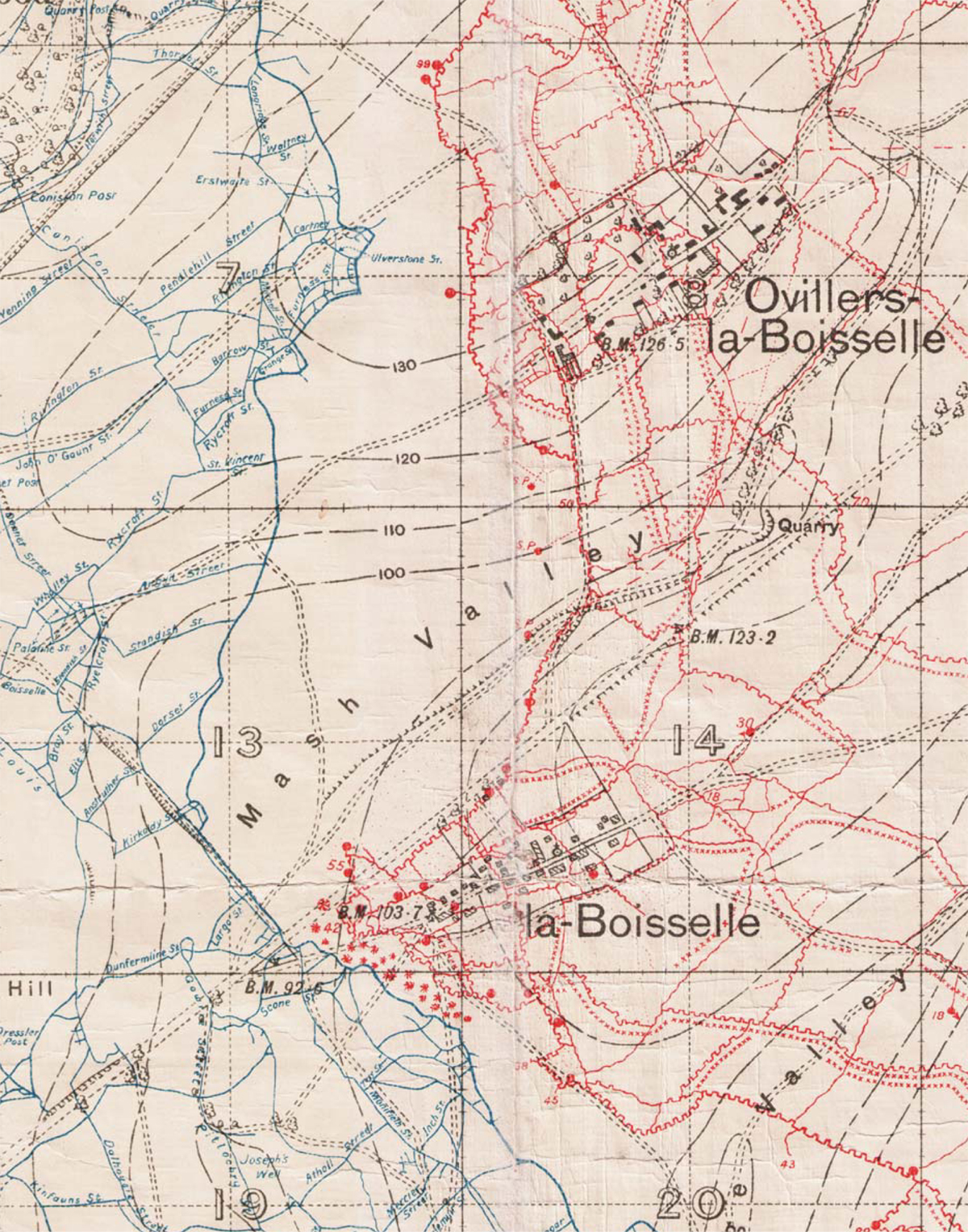

The infamous ‘Mash Valley’ from the ‘Ovillers’ trench map, sheet 57D S.E. 4, 1:10,000, with German trenches, in red, corrected to 27 April, and British trenches, in blue, corrected to 11 June 1916. The red dots are identified as German ‘earthworks’. On the morning of 1 July, Ovillers, at the top of the area shown, was the main objective of the 8th Division assault – but some of the attackers had 700 yards of open ground to cross, overlooked and under fire from more than one direction. The 2nd Middlesex actually entered the German line but suffered 540 casualties, including their commanding officer, who was wounded, and had only one officer and 28 men remaining at the end of the day. The 8th King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry were similarly hard hit, and the 8th York and Lancasters lost 597. The 8th Division suffered a total of 5,121 casualties.

Ovillers was eventually taken during intensive fighting from 15–17 July, the last 128 German defenders being officers and men of 15th Reserve Infantry Regiment and Garde Fusiliers, who were finally winkled out by bombers of 11th Lancashire Fusiliers. Three German machine guns, still operative, were also captured. The Ovillers British military cemetery, designed by Sir Herbert Baker, is just one of several in the area. It commemorates 3,440 Commonwealth servicemen, and also contains 120 French burials. One of the graves here is that of Captain J. C. Lauder, 1st/8th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, son of Sir Harry Lauder, killed in December 1916. The remains of La Boiselle, located at the bottom of the plan on the spur between Mash and Sausage valleys south of what was once the main road to Albert, were attacked by Tyneside Scottish and Irish battalions of 34th Division at the cost of 6,380 killed, wounded and missing − the highest number lost by any division on 1 July.

Men of ‘A’ Company, 11th Battalion, Cheshire Regiment, occupy a captured German position at Ovillers-la-Boiselle on the Somme, July 1916. Note that the trench has been ‘turned’, and is now being defended from its parados, or rear lip. One man keeps sentry, using an improvised fire step, whilst his comrades rest. Picture taken by Lieutenant J. W. Brooke. (IWM Q3990)

In the German system, as laid down in the Infantry Drill Regulations 1906, the attack was described as consisting of ‘firing on the enemy until close range is reached, if this is necessary. Victory is made complete by charging with fixed bayonet.’ Following deployment into skirmish lines the infantry would move as close as possible before opening fire, and though open ground was best avoided or crossed swiftly by ‘well extended forces’, in extremis it could be used for the attack. The desire to press forward was to ‘animate all units of the attacking force’. Despite this bullish approach, organized ‘mutual fire support’, breaking into smaller units to take difficult targets, and rushes were all part of the plan. Rushes were commonly of platoon size units, as smaller bodies tended to break up fire effect, and larger ones made mutual fire support difficult. ‘Regularity’ in the advance of units was positively to be avoided, though interfering with the fire of neighbouring units was strictly forbidden. Before the outbreak of war the British General Staff was in no way complacent about the comparative merits of the Continental infantry. Whilst it was thought that British troops had the edge in ‘musketry’ and ‘minor tactics’, a report of 1912 suggested that the French infantry were superior in marching. British observers noted some units covering 30 miles in a day. The ‘spirit, discipline, endurance and marching powers’ of the Prussians and Saxons in the German Army was acknowledged as ‘in every sense admirable’.

The machine gun was something of a Cinderella on the battlefields of 1914, for though it had existed in its modern form for three decades there was still disagreement about its best tactical use. Performance in colonial wars was not thought to be a particularly good guide as to what might happen when ‘civilized’ enemies, who also had machine guns, were encountered. The models in use at the outbreak of war were neither available in very large numbers nor of particularly mobile designs. Most nations, including Britain and Germany, fielded water-cooled Maxim designs; the French air-cooled guns were mainly of the Hotchkiss type. Water-cooled weapons were better for long periods of sustained fire but required a supply of water and a can. Sometimes this was easier said than done, and many crews had to resort to what Georg Bucher would delicately call the ‘human water spring’ – with the result that a hot gun stank. Moreover boiling liquid gave rise to steam which could sometimes reveal the position of an otherwise well-placed gun. Air-cooled guns did not suffer these inconveniences, but were less useful in prolonged actions. All machine guns were heavy – though the air-cooled models were generally a little lighter – and the British and French guns were mounted on tripods, the German MG 08 on an elaborate ‘sledge mount’. The Germans had kept their machine guns in separate units until comparatively recently, but then, like the British, had allotted them, two per battalion, to the infantry, though Jäger battalions had a complete company of six guns. British regulations described the machine gun as a weapon ‘of opportunity’. In the event they were somewhat cumbersome in the attack, but would prove devastating in defence.

French gunners with the 8mm Hotchkiss machine gun. The air-cooled Hotchkiss was a reliable weapon, usually fed from strips of 24 or 30 cartridges. Despite the lack of a water jacket the equipment was still heavy – with the gun and the mount weighing about 53lb each. (Author’s collection)

One thing that contemporaries did agree on was that, whilst they occupied a relatively small space, machine guns were remarkably powerful – equalling from 30–50 riflemen depending on the authority quoted. Moreover, as an Austrian report translated by the British General Staff in 1911 observed, the effect of machine weapons was not just physical:

When we think of the heavy loss which can be caused by machine guns over a restricted area in a very short period of time we see that the influence which they exert on the enemy must be very great. Nor must we forget that the bullets which fail actually to hit have also great moral effect if they get close to the enemy. They force him down under cover, disturb his aim, and thus enable our own infantry to fire more effectively.

In the British Army at the outbreak of war the old .303 Maxim was already slated for replacement by the Vickers model of 1912, an essentially similar, but somewhat improved gun. George Coppard remembered the Vickers as the most successful, being highly efficient, reliable and compact:

The tripod was the heaviest component, weighing about 50 pounds; the gun itself weighed 28 pounds without water. In good tune the rate of fire was well over 600 rounds per minute, and when the gun was firmly fixed on the tripod there was little or no movement to upset its accuracy. Being water cooled, it could fire continuously for long periods. Heat engendered by rapid fire soon boiled the water and caused a powerful emission of steam, which was condensed by passing it through a pliable tube into a canvas bucket of water.16

So much for the technology and tactics – which might have worked were it not for a number of strategic and technical matters that confounded all expectations of a swift and emphatic encounter. One important factor that made the occurrence of trench warfare more likely on the Western Front was the relatively fine balance of the opposing forces. Germany was strong, but needed to retain a defence in the East against Russia: her seven armies involved in the initial onslaught in the West therefore totalled approximately 1.5 million men, with the greatest concentrations at the northern end of the front. Against this France could initially dispose just under 1.2 million, but with the enemy advance into Belgium other forces also came into play. The Belgians numbered approximately 120,000, and, though poorly equipped in some respects, on the defensive they benefited from existing fortifications, notably those at Liège and Namur. These forts of the Meuse were not new, having been completed in 1891; nevertheless they were extensive, involving 21 individual forts, concrete shelters and an investment of 72 million Belgian Francs. Their presence impeded enemy use of the Belgian railway system. The arrival of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from 12–17 August added another 100,000 men. Though traversing Belgium gave more space in which to deploy, and offered the tempting prospect of avoiding the main concentration of French forces, it also increased the distance the German armies had to travel. The spearhead of the German offensive, First and Second Armies, would strike Belgians, British and French in turn – and would cross hostile territory, while the British and French were welcomed as friends.

With time any initial German numerical advantage evaporated as the Entente powers gained strength faster than their enemy in the West – and more effort was required to hold in the East. In his memoirs von Falkenhayn went so far as to claim that as early as mid October 1914 the German Army was significantly outnumbered on the Western Front, having just 1.7 million troops to the 2.3 million commanded by France and its allies. This is something of an exaggeration; nevertheless Germany could never bring as many reinforcements to the Western Front as her opponents, at least until Russia finally capitulated. We may therefore see that although it proved possible to create local advantages on specific sectors the total numbers deployed on either side at the start of war were similar. When we consider that modern commentators expect that successful attacks will require perhaps three times the force of a prepared defence, the difficulty of achieving any decisive opening campaign becomes apparent.

Sheer numbers also created inertia. The dramatic European campaigns of earlier centuries had been mounted by much smaller armies, formed from smaller populations, with less effective communications technology. In simple terms this had meant that previous armies fighting in the ‘cockpit of Europe’ had more space and time in which to manoeuvre. There were simply not enough troops to maintain continuous lines across the Continent, and no observation aircraft or telephones to provide early warning. Forces could, and did, slip around each other, and sometimes remained undetected at relatively short distances. In 1914 the Germans quickly ran out of physical space, though doubtless the inescapable mathematical calculation of men and frontages had been one of the factors influencing the decision to enter neutral Belgium in the first place. On the right the German First Army, under Kluck, has been calculated as packed to a density of 18,000 men per mile of its front, whilst even Sixth Army, which was spread over 70 miles on the least crowded sector, had 3,100 men for each mile. As events would prove, simply cramming more men into less space did not make matters easier. Railways did speed troop movement behind the lines, and created what has been famously dubbed an opening ‘war of timetables’, but once the railhead was reached mobility slowed to walking pace. The attack being joined, railways and roads favoured the defender who could now usually move forces more quickly than the attacker. The ‘miracle of the Marne’ was at least in part due to the ability of Joffre to reorder his forces to the left-hand end of his line under Maunoury, meeting strength with strength.

The technical improvement of weapons also played their part in the stalemate. In the opinion of Marshal Foch, commenting on 1914:

Generally speaking, it seemed proved that the new means of action furnished by automatic weapons and long range guns enabled the defence to hold up any attempt at breaking through long enough for a counter-attack to be launched with saving effect. The ‘pockets’ which resulted from partial attacks which were successful and seemingly even decisive, could not be maintained, in spite of very costly losses, long enough to ensure a definite rupture of the adversary’s line.17

More men with more effective arms certainly made closing with the opposition or breakthrough more difficult. In 1814 the musket-armed infantryman would have been lucky to achieve three aimed shots to an effective range of 100 yards; by 1914 the magazine rifle made ten or more rounds per yard to 500 yards perfectly practicable. Artillery, with a rate of fire of perhaps one solid round shot per minute to 1,000 yards, had advanced to a state where shrapnel shells were being thrown ten times per minute to much greater ranges. Machine guns, which had not existed at all in 1814, were effective surprise or defensive weapons, creating ‘beaten zones’ out to ranges of hundreds of yards. Such walls of fire certainly made a significant contribution to the creation of the ‘empty battlefield’: units remaining in plain sight of the enemy for very long were likely to be crippled as an attacking force.