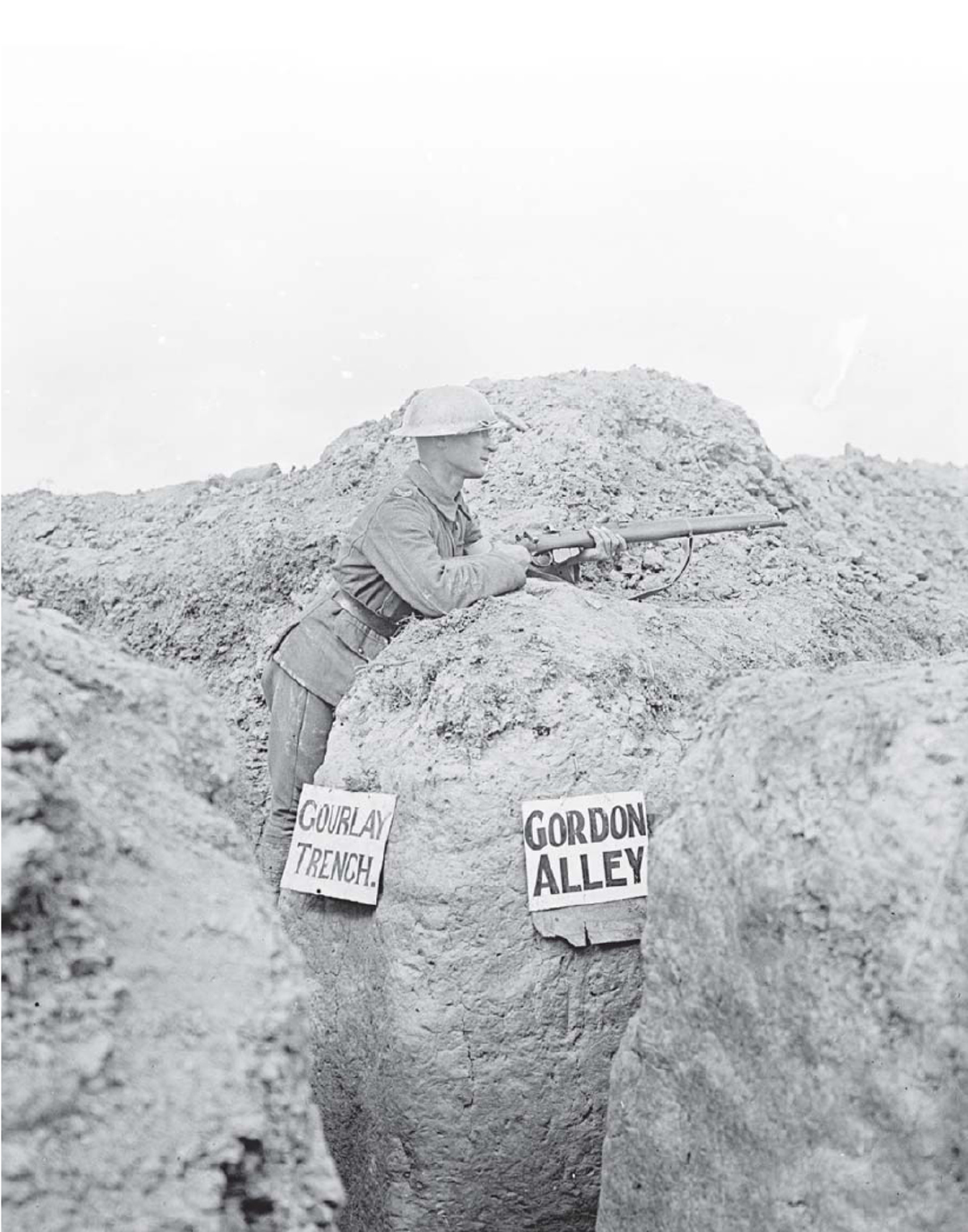

A sentry of 10th Gordon Highlanders, 15th Scottish Division, at the junction of Gourlay Trench and Gordon Alley, Martinpuich, Somme. Though neatly named the trenches are unrevetted: the final portion of the wrecked village was not captured until 15 September. In some places where trenches were very narrow or crowded, one-way systems were operated. (IWM Q4180)

By 1915 the trench struggle was recognized as a special type of war requiring new regulations to govern the day-to-day activity of the units that manned these ossified and heavily protected battle lines. This was what Edmund Dane would memorably dub ‘Trenchtown in the Making’. In the British instance many battalions, brigades or divisions modified instructions issued by the General Staff to suit local circumstances, or produced their own ‘Trench Standing Orders’. Many of these directions contained common elements such as notes on how to enter and exit the trench system; a basic daily routine; a list of stores to be accounted for; a list of paperwork to be kept complete; instructions on sanitation, cleaning and dress; rules on sentries and salvage; and anti-gas preparations. These basics of trench life are often picked up fragmentarily in soldiers’ memoirs, but have rarely been examined systematically – as perhaps they should, since they can provide a surprisingly complete picture of the soldier’s life in the trenches. Some orders, such as those of the 2nd South Lancashires from November 1916, laid out a full daily timetable:

| (Time unspecified) | ‘Stand To’ |

| 8am | Breakfast |

| 8.30–9am | Washing and cleaning of dugouts |

| 9–12.30am | Work |

| 12.30–2pm | Dinner |

| 2pm–4.30pm | Work |

| 4.30–5pm | Tea |

| 5pm | ‘Stand To’ |

Part of the French town of Armentières seen from the air. Closest to the camera can be seen the distinctive crenulated outline of a fire trench: zigzagging communication trenches follow hedge and tree lines back towards the ruined suburb. (Author’s collection)

Men who had been on night duties were excused morning activities.

The first action of a unit about to commence trench duty was a ‘preliminary visit’, usually performed by company commanders accompanied by company sergeant majors (CSM). The purpose of this reconnaissance was to examine the trenches, make a tactical appreciation, note the locations and numbers of listening and other posts, and to allow the CSM to make lists of stores present, or required, during daylight hours. Materials were then signed for, either counted or as ‘unchecked’. Hot on the heels of the preliminary visit came the battalion specialists, machine gunners, signallers and snipers – also during daylight. This enabled vital points to be manned and firepower and communications put in place before the very vulnerable moment when the bulk of the troops were set in motion. Finally the main body moved in under cover of darkness. As was explained by the Trench Standing Orders: 124th Infantry Brigade:

The strictest march discipline will be maintained by all parties proceeding to, or from the trenches. An officer will march in the rear of each company to ensure that it is properly closed up. Reliefs will be carried out as quietly as possible. No smoking or lights will be allowed after reaching a point to be decided on by Battalion Commanders. Guides at a rate of one per platoon, machine gun, or bombing post will invariably be arranged for by Brigade Headquarters when Battalions are being relieved, a similar number of guides will be detailed by them to meet relieving units.

Ideally the relieving unit would move into the walkways behind the fire steps, each platoon smoothly relieving a similar number of men – so ensuring that fire positions remained manned, and no post was inadvertently left unguarded. Such was the theory; but in darkness, and especially under fire, things could easily go awry. Near Lesboeufs, on the Somme, Sidney Rogerson participated in a relief that took seven hours. On the previous day his battalion of the West Yorkshires had departed punctually, before dawn, each company guided by a member of the Devonshires. The route crossed a valley of shell-ploughed ground on the way to Dewdrop Trench, a former German reserve line, whereabouts the ground was ‘carpeted with the dead, the khaki outnumbering the field grey by three to one’. Desultory shelling accounted for two men. Two companies occupied this first position, but the remainder had to wait for the following dusk to struggle through mud like ‘caramel’, into which the feet stuck fast with every step, looking for forward trenches which had been created by joining shell holes. None of the niceties had been performed in advance. At last:

There followed much jostling, scrambling and cursing; men floundering in the mud, officers and NCOs wrestling with the farce of handing over receipts for stores and ammunition they not could see, much less count; until at last the Devons were clear and we had taken over the sector.1

An impressive heap of battlefield relics at Péronne. Items visible include German body armour; British, French and German steel helmets; barbed wire; canteens, mess tins and cutlery; ammunition; and petrol containers. The main drawback of a collection like this is that unconnected to their archaeology the individual pieces say little; moreover, red-brown ‘live’ rust suggests that most have a finite lifespan. (Author’s collection)

Men of the Lancashire Fusiliers carry duckboards over the morass of the battlefield near Pilckem, 10 October 1917. (IWM Q6049)

What individual soldiers actually carried with them into the trenches varied, but after a while it became usual for the large pack which formed part of the 1908 web equipment to be left behind with any extraneous bulky items. Later in the war many units published a standard list of what was to be carried into the line. That produced by 42nd Division in February 1918 comprised ‘full marching order without the pack’, but with full water bottle, ammunition, iron rations and two spare pairs of socks; rifle with cover and ‘four by two’ flannelette for cleaning; periscope (if the soldier possessed one); towel, soap and shaving kit; and grenades ‘as ordered’. The steel helmet was worn, but the soft service dress cap was left in the rear with the pack.

One of the first duties of the company commander was to ensure that he was in contact with the units to either side, then re-check the locations of supporting troops, ammunition and machine guns. A telephone report was then made to the battalion commander that the relief was complete. Platoon commanders were normally expected to remain with their men, even if this entailed not having a designated dugout.

Within 24 hours of arrival the company commander was expected to make a more detailed return to his battalion commander. Typically this included: garrison return; notes on the condition of the trench, and its drainage, fields of fire and loopholes; the state of the wire; ammunition and grenade stocks; anti-gas materials and warnings. Additional reports might be required on visibility conditions; enemy shelling – type, amount and direction; any observed results of outgoing fire; casualties; and expenditure of stores. A typical list of stores returned by a company of the South Lancashire Regiment in August 1916 read as follows:

| TRENCH STORES | |

| Bombs, Mills, Boxes [of] | 25 |

| Vermorel Sprayers [anti-gas spraying tool] | 2 |

| Tins of Hypo [anti-gas solution] | 4 |

| Gas Gongs | 3 |

| Rockets [for signalling] | 100 |

| Shovels | 150 |

| Mauls | 4 |

| Axes | 5 |

| Bill Hooks | 3 |

| Loophole Plates | 5 |

| Barbed Wire Rolls | 40 |

| Trench Coils [wire] | 10 |

| Stakes, Iron, Screw [to secure wire] | 25 |

| Stakes | 6 |

| Tins, Petrol | 17 |

| Boxes, SAA [Small Arms Ammunition] | 10 |

| Rations, Iron, 2 Boxes | 40 |

| FORWARD DUMP | |

| Bombs, Mills, Boxes | 60 |

| Rifle Grenades, Boxes | 3 |

| SAA | 3 |

| Rockets, Red, Flares | 48 |

| Rockets, Green, Flares | 1 |

| Barbed Wire, Rolls | 10 |

| Wire, Trench, Coils | 5 |

| Stakes, Iron, Screw | 30 |

| Ladders, Scaling | 5 |

| Rations, Iron, 2 Boxes | 40 |

| Sticks, Rocket | 6 |

| Handsaws | 2 2 |

From the Honnecourt sheet, 57B S.W. 3, 1:10,000, showing the German trenches, in red, corrected to 8 November 1917. Planned in the autumn of 1916 the Hindenburg Line was an arc of new defences behind the existing German front. ‘Hindenburg Line’ was an Allied expression, the general German term being Siegfried Stellung. There were also different names for different sectors, and for the second and third lines backing the outer crust. The most important elements included the Wotan Stellung from near Lille to St Quentin; the Siegfried Stellung proper, from Arras to St Quentin; the Alberich Stellung; the Brunhilde Stellung; and the Kriemhilde Stellung, which extended at far as Verdun in the south. Codenamed Operation Alberich the retreat to the Hindenburg Line in the spring of 1917 straightened the front and spared the use of perhaps ten divisions, easing manpower problems, whilst the Allied armies were forced to advance over a wasteland – part created by previous battles, part by a ruthless ‘scorched earth’ policy. It is less often noted that the move also enabled the Germans to build their new defences in the best possible locations. Construction lasted about four months, and the workers included not only Germans but also local labour and Russian prisoners. Basic design elements included an anti-tank ditch, multiple obstacle zones and trenches, and concrete works.

This detail of the main line at Basket Wood, seen here, was located behind the additional cover of the St Quentin canal, and includes the formidable strong points of the village and quarry of la Terrière. The outposts were further forward on the canal line, and machine gun and observation posts, some linked to the main line by saps, may be seen west of the village. The major obstacle zone is massive, having four belts of wire in front of the first fire trench. Communication trenches connect with a second line of fire trenches, which are themselves covered by two more belts of wire. Screens and further MG and observation posts cover the back of the main line, before the second or Catelet line is reached. The various small red rectangles represent dugouts, listening posts and concrete works; red dots other earthworks. Behind the Catelet line, not seen here, was the Beaurevoir line – another double trench zone defended by two or more obstacle zones.

A German front line Granatenwerfer post, showing two model 1916 weapons, and operation by means of a lanyard allowing the firer to remain under cover away from the launchers. The Granatenwerfer spigot mortars are mounted on a raised platform with sandbags weighting their bases. The small bunker provides storage for projectiles, or emergency cover during surprise bombardment. The fin stabilized fragmentation round weighed just under 2kg, and had a range of up to 500 metres. Allied nicknames for the weapon and its bomb included the ‘Priest’ and the ‘Pigeon’. (Author’s collection)

Front line German observation and gas alarm post c.1917. The trench features a sturdy fire step, and revetment of wood and wattle, though the overhead cover is at best splinter and rain proof. One man watches using a concealed periscope with a rifleman on guard. Foreground right is the gas alarm bell, and grenades hung by their belt hooks for convenient close defence. (Author’s collection)

Often company commanders held a ‘Company Meeting’ in the evening at which some of the Platoon commanders and NCOs were called together. Here they were given work schedules, briefings and sometimes a chance to ‘discuss’ other matters. The fact that only selected personnel were present meant that enough were left at their posts in case of attack, and at the same time gave the company commander freedom to air selected issues with specific subordinates. One of the company commander’s most important companions in his work was the soft-backed Army Book 152, or Correspondence Book, in which was usually recorded not only stores handovers, but copies of reports on raids, casualties, working parties, work reports – and often enough condolence letters to next of kin. Just one of many Correspondence Books that survive is that of Captain Prior M. C., of ‘C’ Company, 8th Battalion, the South Lancashire Regiment, which contains vivid evidence of fighting in the Leipzig Salient area of the Somme during August and September 1916. In it we see that on 28 August five men were killed and 11 wounded. On 29 August the enemy shelled all morning with howitzers and ‘whiz bangs’, so by 3.10am, in the small hours of the next day, Prior could ‘not say definitely how many men are left in ‘C’ Company, but there are approximately 60’. One of the Lewis guns was put out of action on 1 September, but nevertheless supplies were holding out well as there were still 17,000 rounds of ammunition and 120 boxes of grenades in the company position. Though company commanders were responsible for detailed paperwork for individual trench sectors, much more went on at battalion headquarters – home of the adjutant as well as the battalion commander. The work of the adjutant, assisted by clerks, might include not only collating returns but also recording communications between battalion and brigade, distribution of orders, disciplinary matters and noting incoming stores. The adjutant was also responsible for keeping the ‘War Diary’, a daily record of the doings of the battalion that was kept in duplicate, and ultimately retained by both the regiment and the War Office.

Posting sentries, making sure that they were alert and changed frequently, was an important precaution. Standing orders of 75th Brigade for December 1916 were that sentries should stand guard for a maximum of two hours, a time period that was to be reduced in bad weather and at night. Each sentry post was to be provided with a periscope and wooden range card, and each machine gun was to be attended by two alert men at all times. Notes on Trench Routine and Discipline, 1916, suggested, ‘Sentries should always have one hours rest before posting. Bear in mind any physical weakness of a man before putting on sentry, e.g. bad hearing, natural tendency to sleepiness, disability, nerves etc.’ Sentries were also prevented from wearing anything over their ears. Despite wintry weather 2nd South Lancashires’ standing orders of 1916 were very specific:

Balaclava helmets are on no account to be worn by sentries in the trenches. They may be worn by men in the support and front lines, but only in such a way as the ears are not covered up and hearing interfered with. The steel helmet must always be worn.

Men of German 12th Grenadier Regiment prepare to fire model 1914 rifle grenades from a rifle mounted in a metal launching stand in a front line position c.1916. The man nearest the camera has an S98/05 nA bayonet on his belt, complete with Troddel, or company knot. (IWM Q23932)

In the 19th Manchesters word was slow to get round and two comrades of Albert Andrews got ‘names taken’ by the commanding officer for wearing the flaps of their caps down when on sentry.3 Sadly both were killed by a shell when reporting to battalion HQ regarding this offence.

Some old hands would place their rifle, bayonet attached, under their chins – effectively preventing any ‘nodding’ during a quiet shift. If anything the sentry’s job was more important at night when the enemy might be expected to launch raids, and listening was even more vital than looking. Often a sentry covered more than one trench bay during the day, but after dark it was usual to put a man in each. For maximum vigilance some standing orders demanded that the trench should be ‘practically silent’ at night, perhaps with periods of total silence whilst special efforts were made to listen for enemy miners. Sentries usually kept their weapons charged, with a round ready in the chamber, but the safety catch applied. Though the prime purpose of the sentry was early warning of raid or attack, his secondary task was to report the unusual, such as lights at night, increased or deceased activity, and changes to enemy works or wire. According to Corporal Robert Rider, 14th Royal Warwickshires even went so far as to have a battery-powered bell push system installed for sentries in the most dangerous position. The alarm was raised by pushing a button which sounded a bell in the company commander’s dugout.

In the British Army the ultimate penalty for falling asleep on sentry duty was death; but, though widely publicized, this was a sanction carried out extremely rarely. More often officers and NCOs on hourly rounds would kick sleepy soldiers into wakefulness, and remind them of the possible results. In Delville Wood a particularly sympathetic South African junior officer was remembered by his men as saying loudly into the ear of any apparently dozy soldier, ‘are you awake?’ As the only possible answer was ‘yes’, this meant that the man was alerted, and startled, without need for formal action. Sergeant Hall of 26th Battalion Royal Fusiliers was rather less genteel, but his sexual expletives fulfilled much the same function – despite the danger of attracting enemy attention. The young E. C. Vaughan, working ‘by the book’, put a sleeping sentry on a charge – but a more experienced colleague pointed out the possible consequences, so the man received a thorough bawling out instead. The records of 1st Irish Rifles also reveal that even when cases of ‘sleeping at post’ did reach Courts Martial, lesser punishments were usually inflicted. No fewer than nine men of the battalion were convicted, of whom two were briefly condemned to death – but not one was actually executed. The penalties finally handed down ranged from a very stiff ten years’ penal servitude, down to as little as a suspended one-year sentence.4

Christopher Stone, a junior officer with the 22nd Royal Fusiliers, described a typical routine night round of his sector of the Cambrin trenches in December 1915:

Most of the trenches have foot boards laid down in them which keeps them fairly clean but greasy. I go up the communication trench first of all… Macdougall is said to be out in front by himself examining the wire. I go on to the fire trenches and then turn right handed. It’s all zigzag of course: a bay and then a traverse, a bay and a traverse, endlessly from the North Sea to the Swiss frontier without a break! In about every third bay there are two sentries standing on the fire step and looking over the parapet. At the corners of the bays there are often glowing braziers and men sleeping round them or half asleep: and you pass the entrance to dugouts and hear men murmuring inside, and the hot charcoal fumes come out. On and on: sometimes I clamber up beside the sentries and look out. There’s little to see, rough ground, the barbed wire entanglement about 15 yards away, the vague line of the German trenches. If a flare goes up it lights the whole place for about 30 seconds and is generally followed by a good deal of rifle fire. You see the flash at the muzzle of the rifle. If you hear a machine gun you duck your head. The bullets patter along the parapet when they do what they call traversing: backwards and forwards they patter… In my wanderings I come to a sap and go along it – very deep mud here that nearly pulls off my boots – 100 yards out towards the Germans, and at the end find three or four bombers on guard in case the Bosche tries to come across.5

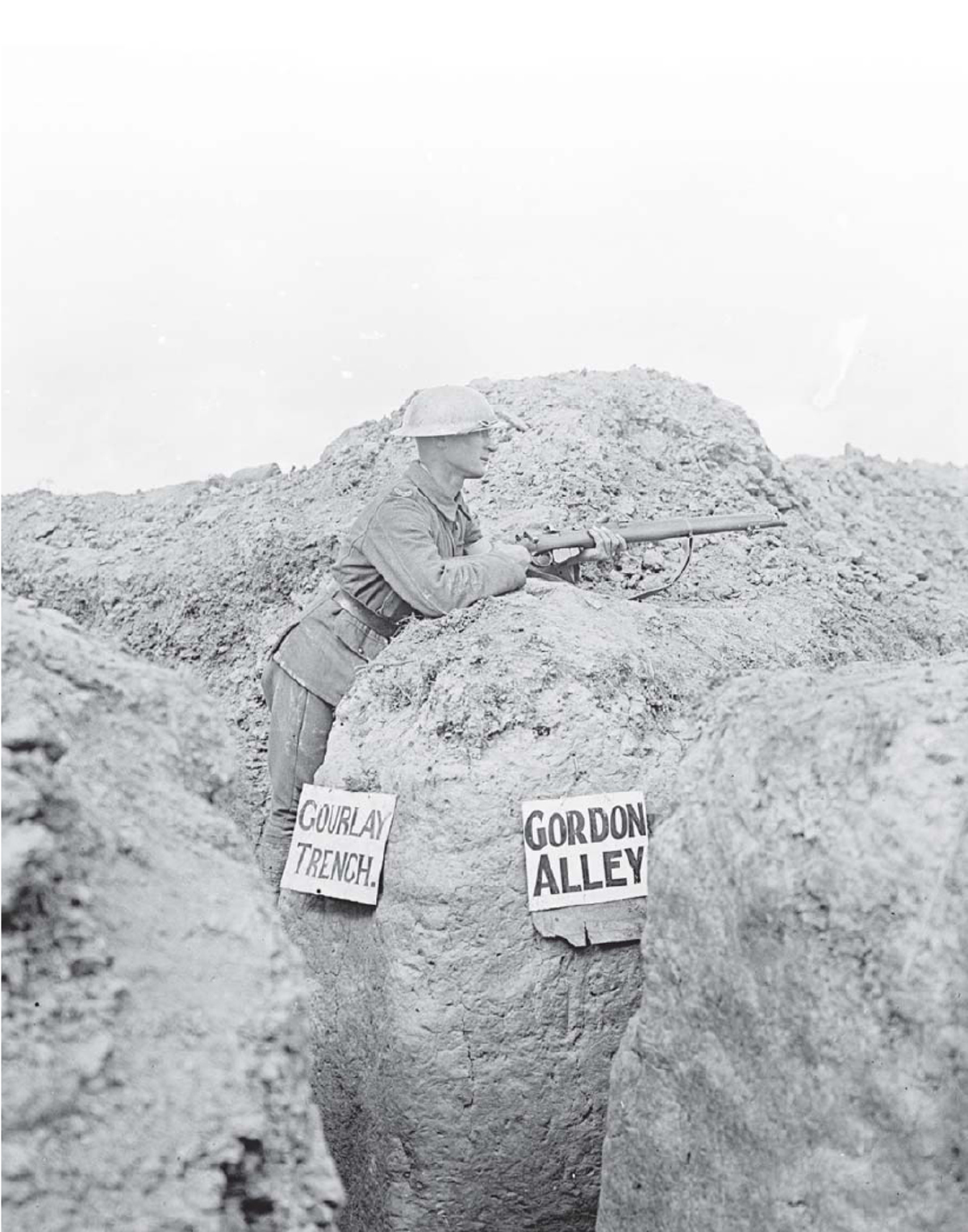

True words spoken in jest: a cartoon postcard showing Tommy standing in water, heavily laden, and lost on his way up to his company in the trenches. The name boards are not as unrealistic as they look – without a potentially suicidal look ‘over the top’ the trench system could appear very much like a directionless maze. Troops therefore followed names, or looked out for distinctive features such as a wrecked piece of heavy equipment or even an unburied body. (Author’s collection)

Early in the war whole units had been forced into the front line fire trenches, sometimes shoulder to shoulder in an effort to bring maximum weaponry to bear: but in the face of artillery massed troops soon suffered heavy casualties – even within the protection of the trench. The shambles seen by Claude Prieur, an officer of the French Fusiliers Marins at Dixmuide, in November 1914, was by no means exceptional:

The trench began to choke with wounded and the dead. The men of the 11th Company, and Belgian machine gunners who had taken refuge. The scene caused the morale of our men to plummet: they were driven to distraction. All attempts to prevent them running were as nothing – they were completely done out. Others lay on the floor of the trench without shooting, and they were taken prisoner.6

After such early mistakes with overcrowded trenches British instructions acknowledged that, in daytime, ‘front line trenches should be held as lightly as compatible with safety’. Brigade and battalion commanders were therefore encouraged to regulate garrison strength to match the tactical situation, and to take advantage of whatever supports and communication trenches were nearby. The basic minimum was to add some snipers to the sentries, and position a few bombers covering any disused communication trenches, or places where the enemy line ran uncomfortably close. As a rough yardstick Notes For Infantry Officers on Trench Warfare recommended that at night at least one man in four, and by day at least one man in ten, should be ‘on lookout in each trench’. This could be regulated quite easily by regarding six men under an NCO as a basic group for a section of trench, and two men would be on watch at night, and one during the day. The number of groups required would be varied to match such circumstances as the proximity of the enemy trenches and nature of the ground.

A sentry of 55th (West Lancashire) Division uses a mirror periscope in the front line trenches at Blaireville, 16 April 1916. In this simplest of devices there is only one mirror, so that the soldier places the mirror on the rear lip of the trench and actually observes with his back to the enemy. The original steel shrapnel helmet seen here was patented by J. L. Brodie as early as August 1915, with an updated model produced from early 1916. It was well nigh universal in the British trenches by mid 1916. (IWM Q534)

The 2nd South Lancashires’ orders from 1916 stated specifically that one officer per company and one NCO per platoon would be ‘on duty’ at all times. Both the duty officer and the NCOs would patrol their areas frequently. In addition to normal duties of those in charge of sections, NCOs in charge of trench sectors were expected to be knowledgeable regarding the geography and dangers of the trench system, and to be able to pass on relevant information to the men. Specific points they needed to be acquainted with included ranges to defined objects, and tactical features such as enemy trenches; the positions and names of neighbouring garrisons and listening posts; the presence of friendly parties and patrols; routes to important locations such as headquarters, and danger spots. Naturally NCOs also had a role in relaying standing orders. Commonly men in the front line trench were given discretion to fire as and when an opportunity presented itself, but if large or important targets were seen these were to be reported up the chain of command and machine guns or supporting weapons alerted. Sleeping in the fire trenches at all was generally discouraged if there were support trenches nearby.

However a trench was garrisoned, the assumption that it was to be held tenaciously remained common currency until late in the war. The 1917 Trench Standing Orders of 63rd Royal Naval Division stated explicitly that ‘the main front line of trenches must be held to the last, whatever happens’. Whilst lines were thinned out it was the duty of the immediate supports to reinforce the front ‘without waiting for orders’, or to ‘counter-attack at once without hesitation’. Commanders new to the line were to make plans for such counter-attacks, making particularly sure that key positions were accounted for. Launching counter-attacks quickly was vital since if an enemy was allowed to establish himself, attempting to retrieve the situation was likely to be ‘very difficult and costly’.

Before dawn, at the time of greatest danger, came ‘Stand To’, when the garrison stood ready to arms, a moment also usually chosen for the inspection of men and weapons. A dirty rifle was accounted a particular sin, and to avoid clogged mechanisms and continuous cleaning many men took to covering the action with an old sock. Later they were issued canvas breech covers. Ammunition might likewise be inspected with a view to avoiding malfunctions. According to Notes on Trench Routine each platoon was to have one or two boxes of ammunition to hand in addition to what they carried, and each trench bay was to have a further emergency box, with its wooden lid ‘eased’ ready in a recess. In the trenches the usual instruction was for equipment, including ammunition pouches, to be worn at all times. Though seen in many photographs the untidy festooning of men or trench with cotton ammunition bandoliers was officially discouraged. There were also frequent prescriptions against the wearing of greatcoats in the front line trench, and early in the war Henry Williamson, with the London Rifle Brigade, recorded that his own became so sodden and heavy that he hacked off a length in desperation.7 Henry Ogle much preferred the leather jerkins and cape-style groundsheets that appeared later in the war.8 In some units Stand To was at a set hour, or a given period before daylight; however, particularly canny commanders did not publish a set clock time, since this would enable an alert enemy to lay his plans accordingly. Often there was also a dusk Stand To, and the whole procedure, including inspections, might last more than an hour. When trouble threatened Stand To could be extended almost indefinitely. When 55th Division was in imminent danger of German raids or attack in May 1918 elements were kept on Stand To all night, several nights running.

A trench scene showing German soldiers posed with a captured Maxim gun. Other details include the use of a loophole plate, and right, a trench periscope. The shaft of the periscope has been shrouded in fabric to blend more effectively with the sandbag parapet. The troops carry slung gas mask tins. (Author’s collection)

Rum might be issued after Stand To. The letters ‘SRD’ on the ceramic rum jars were the subject of much irreverent speculation, but actually stood for ‘Supply Reserve Depot’, which was where the containers came from. Though some were teetotal, many troops appreciated the morale-raising quality of a communal tot of fairly rough alcohol after the strict observances of Stand To. From the point of view of officialdom the key factor was to ensure limited quantity but reliable and equal distribution. Quite naturally many men wanted more, and a rum jar was prized loot. To prevent this, many units placed guards on their supply and followed the rule that rum should be issued and drunk in the presence of an officer. True alcoholics were reasonably rare in disciplined units, most being weeded out before they actually reached the trenches. Perhaps paradoxically, alcoholism was more possible amongst officers who carried the stress of responsibility as well as the common dangers and discomforts of the front line – and were able to afford to have spirits sent out to the front, or provided through the officers’ mess.

After morning Stand To it was usually time for the company commander’s morning rounds, just one of many being described by the chronicler of the 1st/4th Loyal North Lancashires in late 1916:

After breakfast comes cleaning and inspecting rifles, while the Company Commander, who has already had a look round and detailed the day’s work to the Company Sergeant Major, completes and sends down by runner to the Battalion Headquarters his Trench State and account of ammunition expended; then adjusting his Tube helmet and box respirator and tightening his belt carrying his revolver and glasses (it is a standing order that everyone must wear his equipment all the time in the front line), he sets out to inspect his lines, finding, if he knows his job, a cheery word for all and sundry, and receiving often better than he gives, taking stock of everything, including slackers, and generally tuning up for the day, well knowing that if he misses anything, the Commanding Officer, or, worse still, the Brigadier, will spot and strafe him! Each sentry post has its standing orders pinned up on a board, with a duty roster showing each man’s work through 24 hours, and ensuring that each gets eight hours in which he may try to sleep, and a sheet for intelligence, which is collected by the intelligence officer every morning when he visits the sniping post. ‘Dinners up’ is the signal for a general break and a repetition of the breakfast scene, but the food is stew or roast meat and potatoes or rissoles. At 1.30pm casualty returns and special incidents have to be at Battalion Headquarters, and at 3.30 a report on the direction of the wind.9

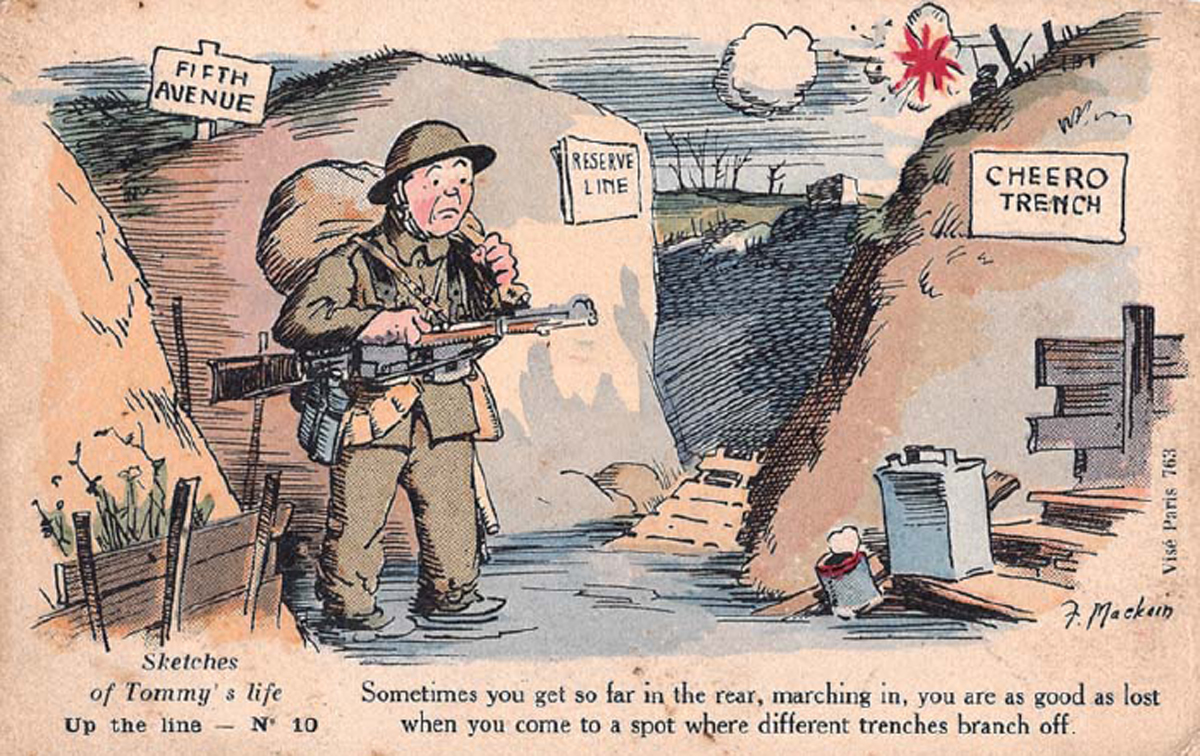

Illustrations from Notes on Trench Warfare for Infantry Officers, Revised Diagrams, December 1916, showing sunken wire entanglements, a diagrammatic sketch of portion of a front line, methods of defence of communication trenches and deep dugouts for one platoon. (Author’s collection)

Many units offered more extensive advice to their officers than that given in official manuals. Late in the war Major General Solly Flood produced a 31-point memorandum for 42nd East Lancashire Division entitled Questions a Commander Should Ask Himself at Frequent Intervals in the Trenches. In this officers were reminded that they were ‘here for two purposes – to do as much damage as possible to the enemy and to hold [their] part of the line in all circumstances’. To achieve these ends it was the unit commander’s duty: to ensure that he knew as much as possible about his territory; maintain contact with the adjoining formations; do everything in his power for the comfort and safety of his men; attempt to leave the trenches and dugouts in better condition than he found them; and check for all signs of ‘slackness and slovenliness’. Interestingly, 42nd Division also advised its officers on the niceties of man management, such as setting an example in punctuality, turn out and cheerfulness, and in taking part in games and skill at arms competitions. Whilst cultivating an aggressive attitude towards the enemy and enforcing strict discipline, officers were also enjoined to ‘be human’; for example, getting to know men’s circumstances and offering whatever assistance might be possible with ‘troubles at home’.

Keeping the trench, and its garrison, clean and in good order was something that took time, even in quiet sectors. Men were encouraged to wash and shave, tasks completed away from the fire trench, and in 124th Brigade the general order was that men should be as clean and smart as ‘circumstances would allow’. Bathing was out of the question until the troops were away from the line: then hastily converted breweries and other premises were pressed into service as rough and ready bath houses and de-lousing areas. Officer Christopher Stone soon discovered that ‘wearing the same pants and breeches for six days and nights without taking them off’ gave him, ‘tremendous sympathy with the working classes’.10 Latrines were kept in good order by designated orderlies with disinfectant. The best system was one of buckets ‘evacuated nightly’, but there were also pit, and various cut and cover systems in use. Notes on Trench Routine carried a strict injunction on indiscriminate urinating. Nevertheless ‘unofficial’ arrangements existed in many areas, of which relieving oneself in an empty tin and throwing it out of the trench as far as possible was one of the least objectionable. On the other side of the line sanitary arrangements were the subject of much Teutonic merriment where the wooden Donnerbalken, or ‘Thunder beam’, over a pit, was the main item of sanitary ware. Interestingly many pictures of German soldiers in the latrines exist, whilst British sensibilities make this subject something of a rarity. George Coppard of the Machine Gun Corps – no stranger to hardship or death – professed himself shocked by such exhibitions.11 Latrines were ideally positioned as far away as possible from fighting and living spaces, whilst maintaining ‘convenience’.

Preserved trench system at Sanctuary Wood. Originally named ‘Sanctuary Wood’ in 1914 because it lay in a quiet sector, by 1915 this had become a key part of the Ypres battlefield. Much of the trench system here has been re-dug since 1918, and despite new industrial strength revetting, soil movement demonstrates the difficulties of keeping trenches open to public access. The site also has a fascinating, if eclectic, museum. (Author’s collection)

Rats, which would ultimately become massive beasts of legend, were not equally prevalent everywhere. It was the worst trenches that attracted the most rats – because they found plenty to eat in the form of corpses and discarded food. Perhaps the most unpleasant and memorable image was the sight of these creatures gnawing on the faces of the dead: but they had other tricks, running over the living in their sleep, or making acrobatic endeavours to get at rations which wary soldiers had hung up within dugouts. Some units had regular rat hunts, clubbing or even shooting the vermin. Photos of the aftermath of particularly successful drives survive, showing the creatures laid out in rows or hung like the game bag of some noble shoot in the Black Forest or Scotland. For Lieutenant N. F. Percival of the Duke of Lancaster’s Own Yeomanry in the Bois Grenier sector rat hunting was a set fixture of the day, for, ‘after breakfast every morning we used to hunt rats which swarmed everywhere’.12

The first line against trench litter was usually sandbags ‘hung up for the collection of rubbish’. Securing bags by means of spent cartridges or bayonets driven into the trench wall was officially discouraged but often seen. Ideally the refuse was divided into used cartridge cases and chargers for recycling, and other waste. ‘Sanitary men’ were detailed to collect and remove the non-recyclable material, carrying it, if possible, 50 yards away from habitation and burying it in marked pits layered with earth and lime. In a perfect world wounded men were sent rearwards with their arms and equipment, but ammunition was left behind. Field glasses, tools and the effects of the dead were sent to battalion headquarters. Enemy rifles and parts of rifles were regarded as salvage, and unusual enemy shell fuses or similar items were supposed to be handed back down the line, like museum exhibits, with labels showing their provenance. Complete dud shells and rifle grenades were exceptions to the rule, being regarded as too dangerous to be moved. Correct procedure was to report them: but in active sectors most were ignored, and in quiet places souvenir-hunting accidents were not uncommon.

Interestingly, certain captured items were regarded as legitimate spoils of war: Extracts from Routine Orders of 1917 catalogued these as German helmets, caps, badges, numerals and buttons. These could be, and often were, sent home. Henry Williamson’s final haul included three German helmets, a cap, two bayonets, a ‘sack of clothing’ and, rather less legitimately and much to the consternation of his nearest and dearest, two boxes of hand grenades.13 Sidney Rogerson of the West Yorkshires had the uneasy feeling that ‘souvenir hunting’ was really a euphemistic looting of the enemy dead. One of his colleagues foraged on a purely commercial basis, selling his artefacts to men of the Army Service Corps who were rarely far forward enough to encounter the Germans. Another, more altruistic soldier went through the pockets of a ‘huge German’ who lay sprawled by a communication trench to find a piccolo, which he promptly gave away.14 What many ‘Souvenir Kings’ prized most was the Iron Cross – small and easy to carry, yet commanding ‘a very good market’.

German soldiers in festive mood: ominously the notice attached to the candlelit Christmas tree tells us that this scene is in front of Verdun in the winter of 1915. The billet is probably a shed, but has been made more homely with photographs and shelving. Many yuletide traditions were held in common by British and Germans, due at least in part to the connections of the royal families in the 19th century. (Author’s collection)

Apart from collecting rubbish the ubiquitous sandbag could be used for almost anything. Henry Ogle with 7th Royal Warwickshires was a great fan of the ‘blessed sandbag’:

I scrounged them whenever there was a chance. We carried rations in them, slung fore and aft over the shoulder; we used them … on our legs; folded they saved hips and ribs from the extremes of cold or hardness or from temporary damp. I used one as a pillow inside my steel helmet in the line or on my boots out of it. I always carried a spare.15

In fact Ogle omitted a few possibilities. With a slit the bag formed impromptu head camouflage; sliced open down one side, a hood for use when carrying dirty supplies or bags of earth; carried into action it was the raw material of protection; cut completely open the material could be used to camouflage periscopes, or made into helmet covers.

‘Trench foot’ was a vexatious complaint – but one that struck very differently at various times and places. In wet conditions, particularly in winter early in the war, it was a veritable epidemic that led to serious debilitation and even deaths. In the summer, in dry sectors, it was rare and far less serious. Medically speaking trench foot and frostbite were similar – both being related to loss of circulation – though trench foot was caused by standing in mud or water, rather than freezing. Both struck hard in the winter of 1914 to 1915 and caught the army ill prepared. A pamphlet entitled Prevention of Frost Bite or Chilled Feet was produced, but by then much of the damage had been done, and over 26,000 men required treatment for one or other condition. Shortly afterwards the subject was revisited in Notes From the Front, Part 3, which noted that cold and wet were the prime culprits and that tight puttees and poor circulation were contributory factors. Yet means of prevention, such as warm dry feet, fresh socks and decent duckboards above water level were often easier to identify than to achieve. Greasing the feet was also recognized as helpful, though naturally unpopular.

Private Edward Roe of the East Lancashires viewed the foot smearing procedure with incredulity. The grease was a ‘tinned transparent substance’ resembling lard:

We are standing in water up to our knees. We are supposed to take our puttees, boots and socks off, smear our feet with this substance (it is solid and cold as an iceberg), put our wet socks, boots and puttees on again and stand up in water to our knees. Well we won’t do it.16

Australians in a trench shelter, Fleurbaix, June 1916. In this example the shelter has been prefabricated as a wooden frame and the sandbagging built up around it. Boards keep the occupants clear of the ground. This arrangement was ideal for ‘box’ or ‘breastwork’ trenches, fabricated on top of, rather than dug into, the ground. More usually shelters were dug into the side of the trench. (IWM Q668)

Roe might not have done, but many did. One unit that took trench foot extremely seriously was 2nd Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers. In the winter of 1914 its cooks saved all grease from cooking, and ‘after stand to each morning the men rubbed each other’s feet vigorously with it’.17 A man from each company was also detailed to the battalion laundry, and a pair of clean socks for every man was brought up with the rations. Socks were also sent from home in huge numbers, so eventually men were throwing them away after a single wearing. The happy result of this obsession was that only one man of the battalion had trench foot that winter, even though wet trenches were frequently occupied. Gumboots and thigh-length ‘trench waders’ gradually became more common, and undoubtedly helped – but were not suitable for duty involving swift movement. Also, as Notes For Infantry Officers pointed out, they were clammy and best kept on only for limited periods. Nevertheless the general incidence of trench foot and frostbite was reduced with time, so that though the BEF grew to many times its original size the numbers treated for these complaints were marginally reduced in latter years. Captain F. C. Hitchcock of the Leinsters records that having frostbitten feet was eventually regarded as ‘disciplinary’ – this added insult to injury but may have encouraged additional care.

In the trenches drinking water was usually stored in rum jars and barrels, and, where possible, brought up in battalion water carts at night. Biscuit tins and camp kettles were also used as impromptu water carriers. Bottled soft drinks were rare, but not unknown, unlike amongst the enemy where bottled mineral water was fairly common. Strict prohibitions were issued against using potentially contaminated streams, wells and shell holes – but in extremis, men isolated during major battles could, and did, drink anything. Whatever the source water was safest boiled, and much of Tommy’s liquid did in fact come from tea, often carried cold in the water bottle. Chloride of lime was the main alternative to boiling, but usually left the liquid unpalatable, if not undrinkable. Sensible officers kept a rough check on the amount of water to hand and stopped washing and shaving if levels ran low, or allowed potentially contaminated ‘surface water’ to be used for washing only. ‘Water parties’ were sometimes needed to fill bottles or collect tins, but were best kept nocturnal and as small as possible to avoid attracting enemy fire.

Tinned ‘iron rations’ for one day, two if possible, were supposed to be carried up to the line with each relief. These were not, however, to be consumed as a matter of course, being intended only to be opened on the orders of an officer when normal supplies were interrupted. Wherever possible cookery was not done in the foremost trenches, but as a company level activity in support areas. Naturally showing smoke during daylight was strictly forbidden. Nevertheless in many places braziers were improvised out of buckets, and small quantities of food and water were heated over candles. Later some troops acquired somewhat more efficient pocket cookers, or primus stoves. Larger commercial solid fuel stoves were occasionally lugged into dugouts with chimneys. Using any of these devices in enclosed spaces carried risks of fire and suffocation, and there were accidents. The recommended way to bring food forward was during the night immediately before it was required, but fumbling with an odd assortment of comestibles in mud and darkness was inviting spoilt food and missed deliveries. The answer given by 124th divisional orders was that the quartermasters should make up each company’s rations and pack them systematically in sandbags. Each bag was to have the company marked ‘on a piece of tin’, a second tag under the first denoting the platoon. The marks, being impressed, could be read by touch. Water and other drinks were often brought up in old petrol cans or large iron ‘dixies’, and memoirs abound with accounts of tainted tea. Nevertheless later in the war there were insulated cylindrical backpacks with screw closures allowing the carrying party free use of both hands whilst delivering tea, stew or other non-solid supplies.

A sentry of the Worcestershire Regiment observing through a loop at Villers, August 1916. This post is actually at a ‘trench block’ built with sandbags and a wooden plank lintel across the trench. This NCO wears regulation 1908 Pattern equipment, and is armed with rifle and fixed bayonet. The breech of the weapon is protected against dirt by a cover, possibly made from an old sock. (IWM Q4100)

Some staples appeared over and over again: hard biscuits, bread, and tins of stew or pork and beans – the latter being mainly beans and a suggestion of pork. Private Dolden, a cook with the London Scottish, recalled that plum and apple jam was issued so frequently that a single appearance of apricot was warmly welcomed.18 ‘Bully beef’ became the stuff of legend, being fried, stewed or simply sliced: but if badly stored, and served warm, might literally be poured from its 12oz tin. For starving Germans late in the war it was regarded as a delicacy – the French were mystified by British ‘bully’ and derided all tinned meat rations as ‘singe’ or monkey. Officially each British soldier was given 4,300 calories a day in mid 1916, a laudable target when achieved. Yet nutritional knowledge was not advanced and fresh ingredients were often lacking, particularly in the front line. Moreover the intervention of the enemy, the weather and a good shaking in a sandbag could turn even good food into an unpalatable mush. Sometimes nothing turned up; sometimes the amounts were so small that neighbouring sections would agree to take rations alternately rather than have tiny amounts more frequently. Acting Lance Corporal Eric Hiscock of the Royal Fusiliers remembered the final division of his section rations as an ‘art form’, with a loaf of bread, stale cheese and other items having to be split into eight precisely equal portions. Albert Andrews of the 19th Manchesters fared rather better – remembering a typical day’s trench rations as bacon and tea for breakfast, a ‘dinner’ of stew, a tea with bread and jam and a cup of tea at midnight.19 The young Ernest Parker of the Durham Light Infantry mused that teenagers were ‘always hungry’ – and like many of his compatriots spent any spare pay in the local estaminets whenever they were accessible.20

During times of particular stress to the supply system, or gluts after the delivery of parcels from home, nourishment turned distinctly bizarre. Lieutenant Roe of the Glosters improvised porridge from hot water, hard biscuits and jam. With the Royal Warwickshires E. C. Vaughan recalled a breakfast of ‘tinned herrings and sherry’, and supervising a work party near Courcelles he once enjoyed the rare treat of sandwiches and a bottle of English beer. Edmund Dane noted a rifleman who ‘imported a box of kippers’ to the front line at Givenchy, whilst Henry Williamson continually pestered his mother for cakes.21 In 1916 the officers of 18th King’s Royal Rifle Corps were not unique in enjoying a full Christmas dinner, but embellishments including curried prawns, caviar and 1906 Veuve Cliquot Champagne probably marked them out as the best diners of the festive season. Early in the war the Germans also enjoyed bountiful Liebesgaben (presents) from home, with sausages, cigars and spirits particularly popular gifts. At Christmas 1914 Martin Müller had almost too many seasonal goodies to carry, including sausages, gingerbread, marzipan, jam, cake and a bottle of concentrated tea and rum.22 Yet plenty was all too brief, and towards the end of the war Ernst Jünger would leave vivid descriptions of surviving on paltry ersatz (substitute) rations, and the delight occasioned by the rare appearance of dumplings or beans. German dried vegetables acquired the well-earned nickname Stacheldracht – barbed wire.

There were some sectors where men felt that they were in the waiting room of death. Places such as ‘Shell Trap Farm’ and ‘Hellfire Corner’ got their names for a reason. One particularly nasty area just south of Passchendaele was occupied by the 3/5th Lancashire Fusiliers in mid November 1917. Officially the great Flanders offensive had ended the very day they had arrived but nobody had told the Germans, or the heavens, that the battle was over. At the end of October the unit had had a ‘trench strength’ of 21 officers and 499 other ranks – but attrition and sickness soon took their toll. Three weeks later 20 men were dead, 39 wounded, seven missing and 70 sick. Of the officers lieutenants Forshaw and Lovell were dead; Lieutenant Simpson wounded. Three more were sick. Of all ranks a total of 142, or just over 27 per cent, were hors de combat even though there had been no attack by either side. As the regimental journal remarked, here ‘the weather and general conditions of life in the trenches was more expensive than the enemy’.

A German soldier fights from a shallow ditch that might once have been a trench, next to the body of a Frenchman. The German wears the new Stahlhelm; the Adrian helmet of the battered corpse lies nearby. Photograph taken by a German official photographer near Fort Vaux during the battle of Verdun, 1916. (G. Theodore Collection. IWM Q23760)

Though active sectors and keen, aggressive commanding officers effectively exhausted both the time and the energy of the private soldier, most areas had some experience of boredom. Some happy places, where the enemy was quiescent, were filled with boredom. In the winter of 1915 the 5th South Wales Borderers battled the elements at Festubert and Neuve Chapelle, but lost not a single man throughout November and December. This their history ascribed to their ‘having learned to work very silently and to be careful not to leave things about to attract the Germans’ attention’. The 10th Lincolns struck particularly lucky near Armentières, in good weather, during February 1916. Here Major Walter Vignoles found the trenches ‘really quite comfortable’ and ‘in good condition’, with the enemy doing no more than containing the British occasionally with small arms fire. Despite the presence of snipers Vignoles’ company was unscathed. In such circumstances amusements were at a premium. Many played cards. ‘Crown and Anchor’ was also a popular gambling pastime, using a fabric playing surface the soldier could pack away in his pocket at a moment’s notice – a particularly useful characteristic given that technically it was banned. Nevertheless many officers winked at its existence, provided that the game was peaceful and not played in plain sight of authority.

Diaries were also frowned upon, though quite a few were kept. Writing letters and filling field postcards was actively encouraged and was a significant morale raiser, though officers censored the outgoing post. Despite this, and specific prohibitions against mentioning units and places, many men managed to convey a surprising amount of information by means of hints, or outright encoding. One method of indicating location was to write that you were ‘back at the same place’ as you were when some memorable event had happened at home. Another was to scatter the letters of a vital word at set intervals throughout the message. Though the Army Postal Service was part of the Royal Engineers who brought the mail most of the way, the last and usually most difficult part of the journey was in the hands of a unit postman – commonly a corporal or lance corporal. Christopher Stone described him as a ‘poor devil’ who ‘trudges about 10 miles a day with a bag over his shoulder through incredible sludge and mush’.23 From 28 August 1914 sending letters home was free: relatives posting to the front paid 1d. Usually, and unless an offensive intervened, delivery took about ten days.

Reading was popular with some, particularly where a unit was static for a while. Perhaps surprisingly, quite a few officers managed to get fairly current newspapers and periodicals delivered directly to the front. These might come by subscription from the publisher, or through an intermediary at home. Many soldiers were given abbreviated ‘Soldier’s Testaments’ or other religious works by societies or well wishers, and other books made it to the trenches in packs, or were found amongst ruined buildings. Divisions and chaplains might have their own libraries, though fewer of those volumes were actually taken to the front line. Trench newspapers were also published by soldiers, for soldiers. These varied in quality and execution, and might actually be prepared in the trenches, or in camps behind the line. Many papers were the product of specific divisions; others were less tidy in their parentage. In the British case trench newspapers generally had a high quotient of humour, leavened with a little news, and brainteasers or drawings.

The majority bore splendidly evocative titles such as The Gasper, The Dump, or The Open Exhaust, but most famous of all was undoubtedly the Wipers Times. This was a 24th Division production, edited by Captain F. J. Roberts of the Sherwood Foresters, who was fortunate to discover a disused Ypres printing works with ‘parts of the building remaining’, and the type spread over the surrounding countryside. With the machinery quickly reassembled by a sergeant who had formerly been a printer, production of the journal commenced with ‘issue one’ on 12 February 1916. Later, when the division moved to the Somme the title changed to Somme Times, and, later still, to BEF Times. In 1918 the March edition was lost to the German offensive, and printing was not resumed until November 1918. Blighty was an interesting periodical, for though it bore many of the characteristics of the ‘trench’ productions, was supplied to the war zone, and contained ‘pictures and humour from our men at the front’, it was actually printed in London and numbered Field Marshal Haig and Lord Jellicoe amongst its patrons. Unlike a good deal of the ‘advertising’ in Wipers Times which was satirical, Blighty carried paid sponsorship from major businesses such as insurance companies, Players cigarettes, BSA and Austin cars.

The French also had a vibrant trench publication market – though distinctively different in tone. Where the British tended to be almost uniformly irreverent, surreal and indefatigably humorous, some of the French material was by turns more jingoistic, philosophical and downbeat. In August 1916, for example, Le Poilu explicitly stated that its purpose was to draw together the ties of friendship of the regiment that had given it life. In 1917 Le Crapouillot became distinctly more cynical and less funny, in tune perhaps with the atmosphere of seriousness and mutiny in the French Army at the time. Realistic or dramatic accounts of actions, deaths and obituaries were all rather more common than in the British papers. Criticism of the home front was also overt, and boiled over into some very direct opinions, as in a piece in L’Echo des Tranchées in May 1917:

There are civilians who cannot approach a man on leave without asking him, ‘Why aren’t you advancing?’ Why can we not make use of this ardour of civilians greedy for offensives? We could take them into the front line trenches and urge them to advance. We bet that anyone returning from such an expedition would no longer enquire why one does not advance.

Though private cameras were banned, photography in various forms did have its place in the trenches. Quite a few officers ignored the prohibition and carried with them a ‘pocket Kodak’, or similar small camera of the type that was coming into use beside the old tripod-mounted wood and brass contraptions of the professional. Most regimental collections contain at least some of the pictures by officer photographers alongside those taken by official bodies, or those passed for release through the press. Moreover commercial photographic studios in and near military camps did a roaring trade throughout the war, and as long as materials were available. Literally millions of portraits of individuals or groups were produced. Most were made as multiple prints and given to friends and relatives, whilst soldiers took pictures of their families with them to the trenches. The most salubrious dugouts usually contained one or more pictures, including perhaps a pin-up of a pretty girl, a cartoon or, less commonly, a more patriotic piece. Eventually the war, and the trenches themselves, became the subject of moving pictures such as the remarkable film Battle of the Somme, which was widely shown in British cinemas. It is estimated that more than a third of the entire population of the British Isles saw this production within months of its release.

Artistic endeavour was not entirely absent from the trenches either, and indeed a whole genre of applied decoration and crafts has acquired the general description of ‘trench art’ – what the Germans called Soldatenkunst. In fact quite a bit of ‘trench’ art was made behind the lines, as cottage industry, or as commercial exploitation of war surplus. Some trench art even originated as a by-product of workers’ free time in UK factories. Nevertheless many pieces were made by the soldiers themselves, sometimes in the front line. Though drawings and watercolours are not unknown, most trench art was three-dimensional and often had some sort of practical element. Common items included letter openers fabricated from discarded brass or shell splinters, vases, ashtrays and boxes from shell cases, walking sticks, rings and crucifixes. Also seen are cigarette and matchbox holders; lamps; miniature tanks; and decorated bayonets and water bottles. In certain sectors soldiers carved their regimental badges into pieces of chalk, or created larger designs as permanent features of the trench. In the very front line music was usually out of the question, except for that most exceptional Christmas of 1914. Nevertheless second line trenches and dugouts could sometimes boast a musical instrument and the odd rendition of a popular ballad. There are even stories of enterprising souls who managed to get a piano underground. Gramophones were certainly seen in HQ dugouts and billets. The officers of 22nd Royal Fusiliers received a ‘Decca’ and half a dozen records in January 1917, though the junior officers would later complain that the choice of music was monopolized by the colonel.

Smoking was so common that non-smokers were marked out as unusual, and cigarettes and tobacco came up with the rations as well as being sent from home. The amount issued appears to have varied, with some getting 2oz a week early in the war, others up to 30 cigarettes later. Pipes had been more popular than cigarettes in the Victorian era, and various wood or briar models now predominated: Henry Ogle of the Warwickshires puffed away on ‘Digger Mixture’ in a corn cob until his mouth ‘felt like pickled leather’. A few, like Corporal Fleet of the East Lancashires, still favoured the old-fashioned clay pipe. Cigarettes appear to have become more popular during the war, at least in part because they were small, quick and convenient – easier to hide from NCOs and the enemy, and less of a disaster if they had to be thrown away. On the other side of the line the traditional long German pipe was sometimes seen, and indeed this was recognized as the mark of a man who had served out his conscription time and passed into the reserves; cigars were also popular until they were exhausted. Germans also received tobacco rations, and when available these were supposed to be two cigars and two cigarettes, or an ounce of pipe tobacco per day. Smoking was widely seen as a comforting tonic for the nerves, and, unlike drink, left the soldier in fighting shape. Unless matches were struck in view of the enemy, or a soldier smoked at the wrong time, it was accepted as completely normal. At Christmas 1914 Princess Mary’s fund sent a special brass presentation box to every British soldier, the majority of which contained smoking materials along with a card. Though very welcome the massive deliveries clogged the already well-used delivery systems. When Private Edward Roe ran out of tobacco he resorted to an unsatisfactory mixture of substitutes including tea leaves.24

A German NCO and his Soldatenkunst, brass shell cases decorated in art nouveau style. ‘Trench art’, as it was known on the other side of the line, was fabricated from almost any found material, including bullets, shell fragments and other munitions, or discarded wood, or carved from chalk and bone. Making trench art could while away hours of boredom, providing souvenirs for loved ones or items for a ready market. Some of the most popular pieces included engraved water bottles and mess tins; letter openers; rings; regimental badges; walking sticks and crucifixes. Though there were exhibitions of soldiers’ work even during the war, not all was made at the front. Some originated from workshops behind the lines, some from prisoners, and many of the lace makers of Flanders similarly turned their hands to commemorative textile designs. (Author’s collection)

How ‘comfortable’, or how ‘diabolical’, a trench system became was dependent on many factors, not least location, weather and enemy action. As early as May 1915 the adjutant of a Loyal North Lancashire battalion was intrigued to discover the ‘elaborate way’ the enemy had dug himself in. In one captured Festubert trench was discovered a dugout room, ‘about 15 feet square, with doors and a window, lined throughout with wooden planking covered in cloth, and furnished with leather covered chairs and a table’. In another was found a ‘quantity of feminine underclothing’, the purpose of which caused considerable speculation. At the same time the ground recently occupied by the Lancashire battalion was described as ‘strewn’ with bodies, and defended only by waterlogged trenches 2 feet deep.25

The ‘working party’ became a feature of life as soon as the trenches were dug, though fortunately it was realized that drawing men from reserve areas rather than the front line trenches, except when the front line trench was needing attention, was the most effective utilization of manpower. For technical tasks they often acted under orders of the Royal Engineers. Working parties repaired support and communication trenches, cleared drainage, prepared supplies, helped to erect huts – and a dozen other things – but often they were ‘carrying parties’ by another name. As such they encountered all the trials of the trench relief, but often under even heavier burdens. As the history of the 1/4th Loyal North Lancashires explained, in bad weather the communication trenches turned into quagmires:

very dirty, being in no place less than boot deep and in many places thigh deep in pestilent liquid mud. The boards placed at the bottom of the trench were quite covered over, and, being extremely slippery, were mainly useful in leading the way to the deeper, wetter, part of the trenches! Working parties at night and in heavy rain had very great difficulty in making progress.26

Near Festubert at 9pm on the pitch dark night of 10 June 1915 a Loyals working party under the splendidly named Captain Crump picked up spades, hurdles and sandbags and headed for the front line trench. Though the distance was less than a mile not all of them arrived, and the time taken was about three hours.

Though there were some long periods in the front line early in the war, and the Germans in particular were forced into semi-permanent occupation, most troops had surprisingly short periods of actual ‘trench warfare’. At Verdun in 1916 the French Noria system of rotating troops may well have saved the battle, for by May, 40 divisions had been passed through ‘the mill on the Meuse’. The idea that trench duty was finite, and that the majority rather than a minority would emerge after a given time, was a considerable boost to morale. In the British instance a division at the front was usually placed with its brigades in line, side by side. At least half the strength was held back from the foremost line, so that each brigade had a battalion each in ‘support’ and ‘reserve’, respectively. Therefore only six battalions of the division were actually facing the enemy in the trenches, and of these only half would be in the fire trenches, posts or immediate supports. At any given moment many men were deployed on tasks behind the line, and Royal Artillery personnel were not usually at the sharp end – unless as forward observers. The Army Service Corps, veterinarians and many other support troops had no real place in the trenches. According to one calculation, therefore, a typical division with perhaps 10,000 infantry usually had no more than 1,000 men in possible ‘contact’ with the enemy, though it needs to be borne in mind that most of the others could be, and sometimes were, subject to often unpredictable shelling.

Personal armour protection of the trench war. The mobile shields mainly proved impractical, but body armour saw some use right up to the end of the war. (Author’s collection)

From the Beaumont sheet, 57D S.E.1 & 2, 1:10,000, showing German trenches in red, corrected to 15 August 1916. The British line is marked in blue outline only, and the hamlet of Auchonvillers (known to Tommies as ‘Ocean Villas’) is just behind the British line, off plan, to the west. Parts of squares ‘10’ and ‘16’ are now occupied by the ‘Newfoundland Memorial Park’ with its famous Caribou statue and preserved trenches. ‘Y’ Ravine, which sheltered deep German dugouts, is clearly marked in the south-eastern quadrant of square ‘11’. On 1 July 1916 British 29th Division attacked this sector with a ‘first objective’ of advancing right through Beaumont-Hamel. The onslaught was prefaced with the explosion of the double mine at Hawthorn Redoubt – which damaged a portion of the enemy line, but also alerted the defenders to the imminence of the attack. Two brigades had gone in before the Newfoundlanders, who now ignored the narrow but safer communication trenches, which were already clogged with casualties, and went over the top ahead of 1st Essex. They met concentrated fire unsupported – whilst bunching to avoid uncut wire.

Much of interest remains in this area. In addition to the visitor centre and trenches of the memorial park there are several memorials, including those to 51st Highland Division and 29th Division, and a variety of cemeteries including the tiny circular ‘Hunter’s Cemetery’ – which is probably this shape because it began as a large shell hole. Recent archaeology has served to emphasize the fact that this area was a battlefield long before, and long after, the tragic Newfoundland attack. Excavation in pasture adjoining the park tentatively identified part of the ‘Carlisle Street’ communication trench, but also discovered trenches of what appeared to be an earlier French design and unearthed masses of small arms ammunition. A large proportion of this was French and bore dates of manufacture as early as 1901, but not later than 1915 – which fitted neatly with the period before this sector was handed over to the British. Other artefacts included French, British and New Zealand uniform buttons as well as water bottles, medical items, tin cans and other ‘domestic’ objects. Remarkably Beaumont-Hamel was not taken until 13 November 1916, when the Highlanders of 51st Division cleared its dugouts and cellars, capturing the staffs of 1st and 3rd battalions of German 62nd Infantry Regiment.

Excavated trench leading to a cellar used as a bunker at Auchonvillers, Somme. The building, now used as a tea room and guest house, was rebuilt after the war. The ‘Ocean Villas’ project, run over many seasons, revealed that part of the trench near to the building had been floored with brick, and also the sequence in which it had fallen into disuse and been back filled. (Author’s collection)

Trench in the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial Park, Somme. Once somewhat disorganized, the Newfoundland site has undergone considerable work in recent years – with, for example, duckboards being added to the trenches, and a new ‘Canadian style’ visitor centre. Most of the barbed wire pickets, still present in the 1970s, and all the trench debris have now gone. Though essentially commemorating 1 July and the 800 Newfoundlanders missing on land and at sea, the park encompasses many memorials and graves to other units, and at the rear the famous ‘Y’ Ravine. (Author’s collection)

Quite how long a unit stayed in the trenches varied according to how active the area was, whether attacks were in progress, and the total number of troops available. One of the longest front line sojourns was that of 13th York and Lancasters, who spent an incredible 51 consecutive days in the front line during the Somme, though from a few days to a week or so in the front line trench was a far more typical average. During big attacks, and particularly when heavy casualties were suffered, it was usual for battalions to be taken out of the front line very quickly indeed – sometimes being extracted within 24 hours. According to the history of the 2nd East Lancashires, describing the latter part of 1916, a ‘normal’ trench tour of duty was 16 days, which might be extended to as many as 24. The battalion was rotated by companies with two in the front line trench and one each in support and reserve. The total time in the front line trench therefore varied from eight to twelve days.

At various times British divisions also enjoyed the comparative luxury of deployments to quiet sectors, or even away from the front. In this respect the British were better situated than their adversaries, who often spent months on the same spot – though with sub-units still rotating between the actual front and local reserve. To mention but a few examples at random, German 1st Reserve Division were in and around Arras for roughly two years up to August 1916, and were then redeployed to the Somme; 16th Bavarian Landwehr were in the Vosges for roughly two years in 1916–17; 25th Hessian Division spent a year on the Somme from late 1914 to late 1915; and the 26th Wurttemberg had similarly been on the Somme for about a year prior to almost total destruction in 1916. As the Crown Prince explained, ‘we did not enjoy the invaluable advantages of our enemies, who were able to make good the wear and tear of nerve strength by frequent reliefs and periods of rest’.27