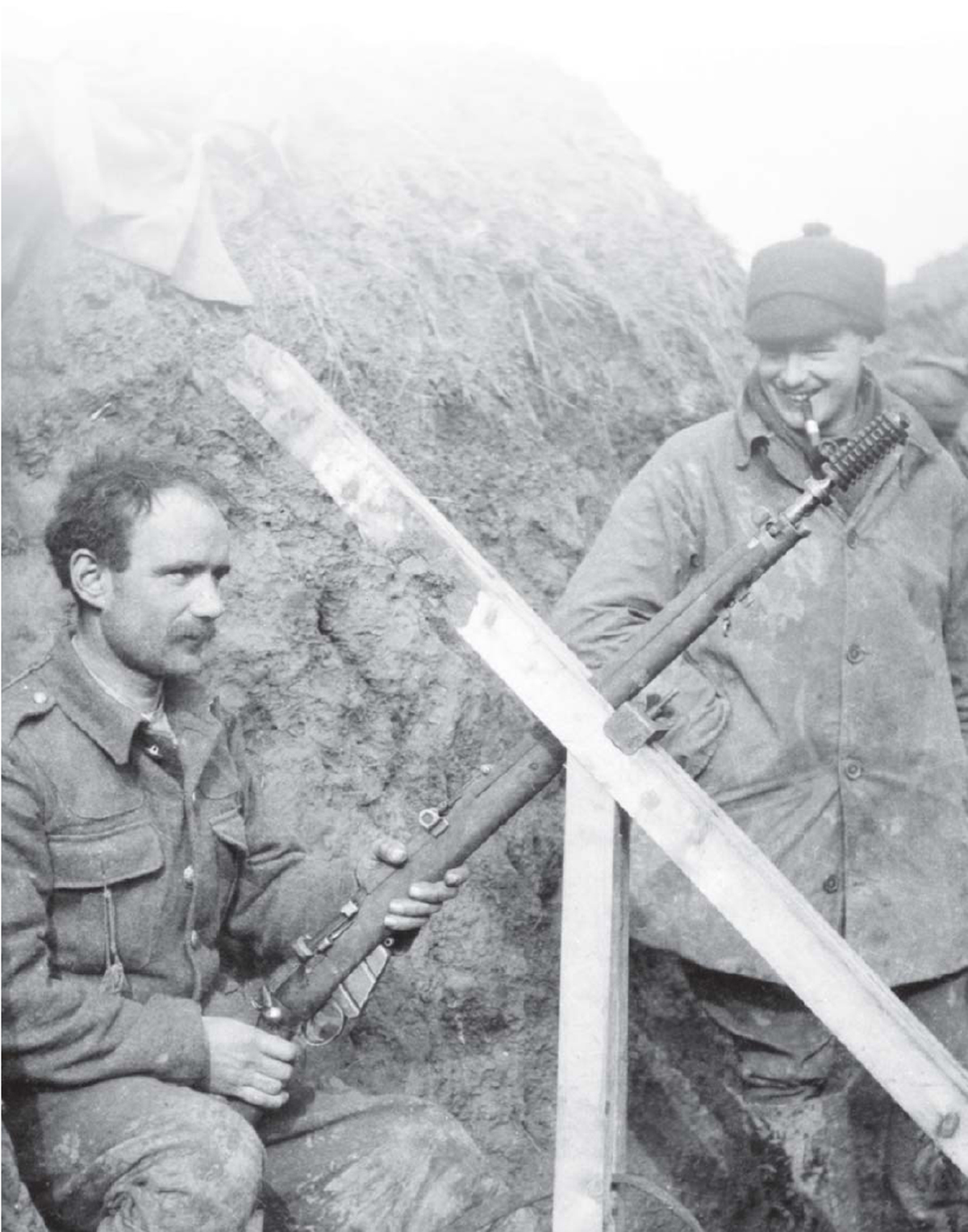

Smoking his pipe 2nd Lieutenant L. J. Barley, 1st Cameronians, watches as a rifle grenade is prepared for firing from a trench at Grande Flamengrie Farm, Bois Grenier sector, February 1915. The wooden firing stand is simply constructed, but allows steady shots at a consistent angle. The grenade is a ‘No 3’ Hale type which had a range of about 160 yards and usually burst into about 175 fragments. Best results were achieved with several rifle bombers firing a salvo, or, failing this, a series of rapid shots to saturate an area. (IWM Q51587)

The commonly held belief that trench warfare and tactics remained much the same from late 1914 to early 1918 is entirely erroneous. Though casualties were undoubtedly high, advances frequently short, and lines often static, the way armies fought, and what they fought with, underwent many changes. Moreover innovations came surprisingly quickly, and were more often delayed by the need to produce new forms of matériel and retrain troops, than by a conservative mindset of command.

The realization that dense formations and failure to dig in quickly were cardinal errors in the face of artillery and machine guns was instantaneous. Henry Williamson recalled that on arrival in France in November 1914 his battalion practised trench digging and ‘artillery formation’ daily – and in any weather. Artillery formation was described by Infantry Training, 1914, as ‘Small shallow columns, each on a narrow front, such as platoons or sections in fours or fives … on an irregular front’. Yet within weeks, if not days, it was recognized that ‘artillery formation’ was nothing like sufficient dispersal. As one general officer explained in Notes From the Front, Part 1, of 1914:

The choice of infantry fields of fire is largely governed by the necessity for avoiding exposure to artillery fire. A field of fire of 300 to 500 yards is quite sufficient… An advance should not be made in rigid lines, but with clouds of skirmishers – 5 or 6 yards apart – thrown forward according to the ground and available cover.

A few months later a new edition of Notes was recommending ‘loose elastic formations’, which were adapted to the ground, discouraging ‘rigid lines’, and suggesting a distance of ‘8 or 10 paces’ between individuals. On the other side of the line pre-war German regulations had already concluded that when ‘platoon rushes’ became difficult ‘half platoons’ and squads might be found more handy. Now, in the face of heavy casualties, orders were issued to decrease the density of attacking formations. Those of Fourth Army appeared as early as 21 August. Nevertheless this was easier said than done where reservists lacked the latest training, or there were attempts to overwhelm the enemy by sheer numbers.

Because trench lines were dug explicitly to defend the occupants against rifle fire, and a static soldier, with his rifle securely rested, had a huge actual and psychological advantage over a soldier moving in the open – who probably could not even see his enemy – the problem of attacking fieldworks came to the fore very quickly. Three answers presented themselves: to cover the approach of the attacker; to attack in new formations; or to use new weapons. All of these ideas had merit, and eventually a new combination of all of them would bring about a revolution in infantry tactics. Progress was swift, but sporadic, and often met with innovations by the defence which would mean that heavy casualties remained the order of the day. In this context, however, it is well worth observing that the greatest slaughters of World War I on the Western Front occurred in periods that were characterized by ‘open’ rather than ‘trench’ warfare. On the German side clear peak casualty figures were reached from August to November 1914, and again from March 1918 to the end of the war. French losses were at their worst in 1914. To this extent British statistics are exceptional, as the army was small in 1914, and July 1916 was catastrophic. Nevertheless British forces also experienced heavy losses from August to October 1918.

Covering the approach of the attacker could mean one of two things: concealing him from view, or physically protecting him from the enemy’s bullets. Of these concealment from view proved easily the most useful – night raids and attack around dawn or dusk were soon common, and smoke and fog were both used. Protection from bullets was far less satisfactory. ‘Sapping’, or extending trenches gradually closer to the enemy, had been practised for centuries and still formed a part of military engineering instructions, where it was seen especially useful as an aspect of siege warfare. Sapping was widely used in trench warfare, and sometimes the diggers were given the additional protection of screens or sandbags. Feld-Pionierdienst, 1911, provides an example in which pioneers erect a sandbag breastwork just ahead of, and to the vulnerable side of, a sap. Saps created useful sniping posts or ‘jumping off’ points, but were a narrow and problematic means to enter an enemy trench system as they would attract fire during their slow forward progress. Feld-Pionierdienst also suggests that advancing troops could carry filled sandbags with them, preferably under cover of darkness, and throw up a small breastwork as the first stage of cover.

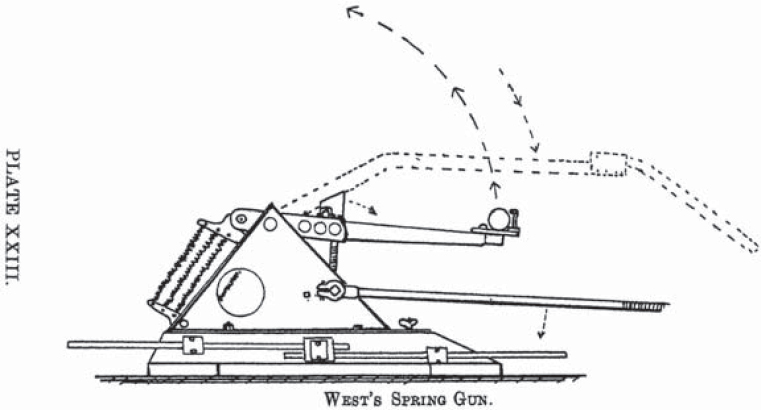

A Stosstrupp or ‘assault squad’ from 40th Fusilier Regiment, festooned with stick grenades and materials to create a ‘trench block’ or reinforce a captured position. The man in the centre of the picture carries a pick and spare sandbags on his assault pack, which consists of a shelter half-wrapped around his mess tin. The soldier on the right carries a gas mask in a soft container, a type later replaced by the familiar squat cylindrical tin. Ammunition bandoliers and a loophole plate are also to be seen in other frames from the same sequence of pictures. Here the leather Picklehaube is worn without its distinctive spike in accordance with regulations of late 1915. (Author’s collection)

Metal shields were used early in the war, some of the first being detached from German machine guns. Der Spatenkrieg even suggested that in the attack some cover from bursting shrapnel could be given to a prone soldier by the blade of the entrenching tool, when its handle was inserted between the pack and body. Such methods were superseded by a variety of small shields, often with prop stands to the rear. The British Munitions Design Committee was still considering ‘portable shields for infantry’ in 1916. Medieval-looking defences on wheels had been used during the Spanish-American War, and were used again, at least experimentally, on the Western Front. Such ideas lingered for a long time but were rarely efficacious for a number of reasons. Perhaps most obviously, to be truly bulletproof a shield had to be tough, fairly thick, and at least large enough to cover a prone man’s head and shoulders. Experiment suggested that 5mm of German armour plate was required to stop a British rifle bullet at 110 yards: a decent shield therefore weighed upwards of 44lb. This weight slowed attackers, who had to be prone to take advantage of the cover, and shields attracted more fire than individuals attempting to hug the earth. Naturally the manufacture and transport of shields in large numbers would have required considerable resources. Most of this effort was later redirected towards the provision of static loopholes.

The widespread use of heavy artillery against fieldworks had been thought unlikely before the war – but developed rapidly. The only real problem was that, initially at least, heavy artillery and suitable high explosive shells and fuses were in short supply. Following shell scandals in 1915 when batteries frequently ran short this would be corrected – then the major issue was the co-ordination of infantry with artillery. Another method of trench clearance that was sometimes successful, if terrain allowed, was to move a machine gun into a flanking position, perhaps by night, then attempt to empty the enemy trench by weight of fire.

The option of giving the infantry a weapon that could be used against holes in the ground was swiftly addressed by the grenade. Grenades had been in use since the late medieval era, and remained in the hands of the engineers as a weapon of siege warfare. Both the French and Germans held some stocks of ball-shaped bombs with pull-type igniters at the outbreak of war, whilst the British had small numbers of a much more technically advanced, but more difficult to manufacture, ‘No 1’ stick grenade which exploded on impact. That grenade-armed pioneers might have a role in trench warfare had certainly been foreseen by the Germans by 1911, and soon after trenches were dug pioneers were allotted to the infantry at the lowest level, sometimes to the extent of adding a single grenade thrower to infantry platoons where night attacks might be expected. Nevertheless in all countries grenade demand outran current production many times, the result being a scramble for new design and manufacture. The new sources of supply would be threefold – new production from home factories; extemporized production in workshops behind the lines; and bombs which the troops themselves ran up from existing scrap materials and explosives already supplied to the artillery and engineers.

Amongst the early bombs made by the troops at the front two basic designs predominated: the ‘Jam Tin’ and the ‘Hairbrush’ (or ‘raquette’), and there were equivalents on both sides of the line. Amongst the British it was the Jam Tin – sometimes nicknamed ‘Tickler’s Artillery’ after a well-known jam producer – that predominated. Basic in the extreme, it consisted of a tin can, packed with dynamite or gun cotton, with a detonator attached to a fuse that projected through the top. Fragmentation could be improved by adding pieces of scrap metal or fragments of barbed wire. The simplest fuses were lit with a match or cigarette; later some were provided with a compound to scratch against a rough surface – or a cap to be set off to ignite the fuse. Notes From the Front recommended practice with dummy bombs, and testing of fuses to determine burn time. Fuses were to be long enough that the bomb could be thrown, but not so long that an alert enemy could dive into cover or even hurl the missile back. Jam Tins were made in many different places, but one of the earliest venues that could claim the title ‘factory’ was the village of Gorre behind the Givenchy–Festubert sector where the sappers and miners of the Indian Meerut Division were ensconced from November 1914.

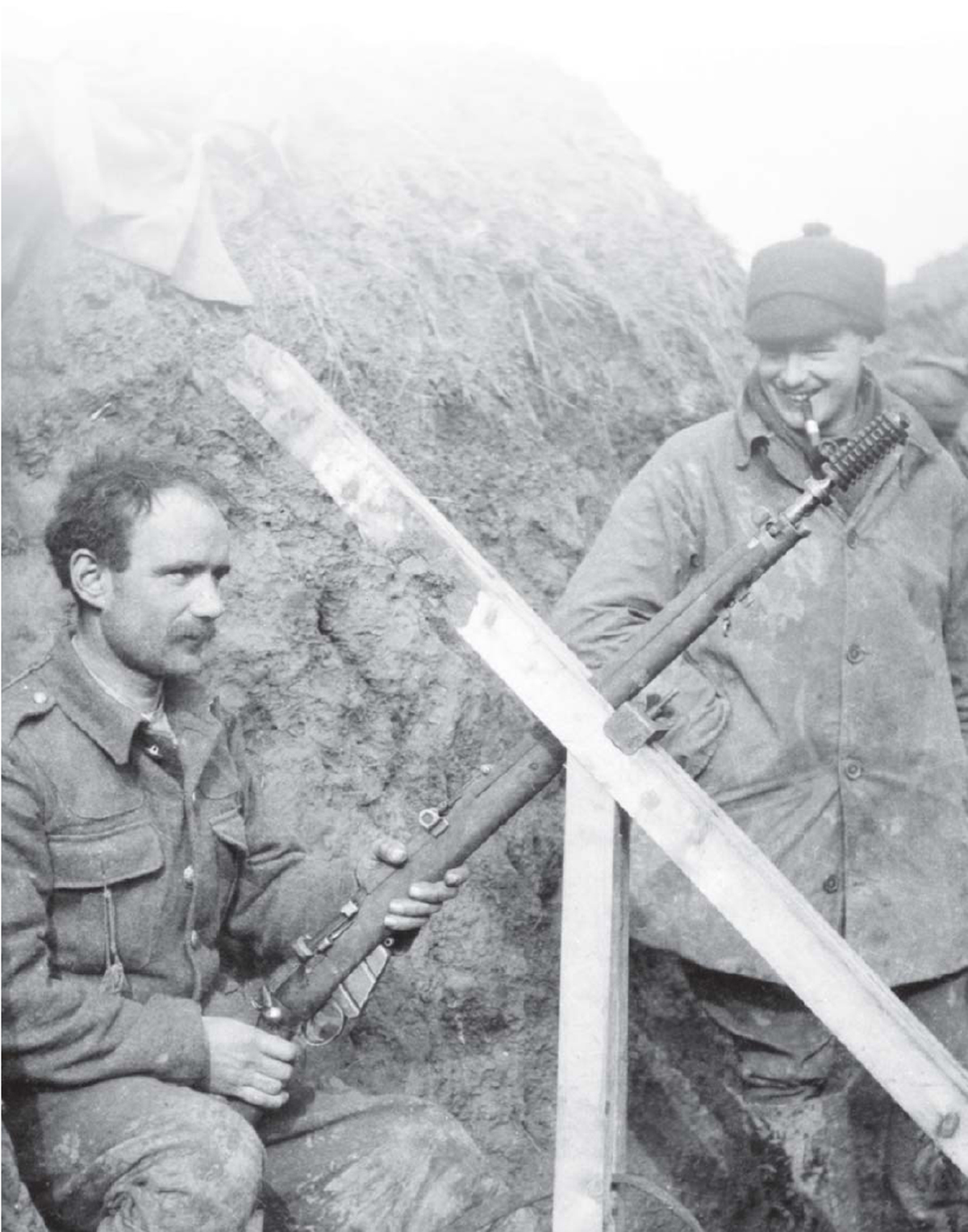

British, French and German grenade types from various manuals. Note the German stick grenades; British ‘Mills’ with lever and segmented exterior; French ‘Tromblon’ for launching ‘VB’ rifle grenades; and British ‘ball’ grenade of 1915. (Author’s collection)

According to Notes From the Front the British improvised ‘Hairbrush’ was about 20 inches in length, with a slab of explosive surrounded by metal fragments within a sacking cover, attached to the wooden handle, again with a fuse and detonator. An Imperial War Museum variant has a tin attached to the backing board. French examples, from the Les Invalides museum, and seen in photographs, vary in detail. Some have nails tied around the explosive, others feature a slot in the wooden handle by means of which they can be slung from a rope around the bomber’s body for easy carriage. The German emergency grenades were commonly known as Behelfsmäßige Handgranaten. Two models, approximating to the Jam Tin and Hairbrush, were depicted in the 1915 Dienstunterricht des Deutschen Pioniers. The tin type was about 4 inches in diameter, closed with a wooden lid, and contained fragments of iron weighing about 0.2oz. The German Hairbrush type was 20 inches long with a large slab of explosive.

Another type devised in the winter of 1914–15 was the British ‘Battye’ or ‘Bethune’ bomb, produced in army workshops in France. Named after its inventor, Major Basil Condon Battye RE, it consisted of an externally segmented small cast iron cylinder filled with explosive, a detonator and an igniter, usually of the ‘Nobel’ type. It was delivered in wooden boxes of 30. Battye was also celebrated for his efforts in bringing electric lighting and heating to dugouts. The so-called ‘Mexican’ grenade – later known as the ‘No 2’ – was a type of British explode-on-impact stick grenade seen in small numbers. Its strange name came about because it was being produced for a commercial contract for Mexico by the Cotton Powder Company of Faversham in Kent at the outbreak of war.

Though Feld-Pionierdienst had envisaged that grenades would be used in the clearance of fieldworks, quite how the grenadier would achieve this in practice was not immediately apparent. Grenades were quickly used in raids, and grenadiers were put in the front line ahead of attacking infantry, and another tactic used at a very early stage was to open rapid fire with other weapons, so allowing bomb throwers to creep forward: but none of these methods yet exploited the grenade to its fullest potential. Only when groups of grenadiers worked together would it be possible to develop new tactics, and this had commenced by the beginning of 1915. In Notes on Attack and Defence it was recommended that attacks should always be well supplied with bombs, and that there should be ‘an organised plan’ to keep the defenders ‘of a captured trench amply supplied with these missiles’.

By May 1915 an ideal ‘Trench Storming Party’ had been devised by the British. This was to comprise upwards of 14 men commanded by an NCO. The men of the party would be divided into four distinct tasks: ‘bayonet men’ to cover the group and take the lead in winkling out the opposition; grenadiers; grenade carriers; and ‘sandbag men’ whose duty was to follow up, block side entrances, and finally form a barricade in the trench at the furthest point of the advance. To provide manpower for these storming parties the ‘very best, bravest and steadiest in an emergency’ were selected for training – with a minimum of 12 NCOs and men per company taking part. By October ideas were further refined in The Training and Employment of Grenadiers, which noted that:

The nature of operations in the present campaign has developed the employment of rifle and hand grenades both in attack and defence to such an extent that the grenade has become one of the principal weapons of trench warfare. Every infantry soldier must, therefore, receive instructions in grenade throwing. It has been found in practice, however, that some men do not possess the temperament or the qualifications necessary to make a really efficient grenadier. For this reason in every platoon there should be a nucleus of one NCO and eight men with a higher degree of training and efficiency as grenadiers than the remainder. These men will be able either to work with the platoon or to provide a reserve of grenadiers for any special object.

British grenades, described left to right. A ‘No 27’ hand or rifle projected phosphorus bomb, capable of causing dreadful burn injuries and ideal for clearing bunkers or creating smoke. The ‘No 34’ Mark III, a small ‘egg’ type ideal for combating the longer range of similar German grenades. The ‘No 36’, an improved 1917 model of Mills bomb, suitable for both hand, or – with the base plate seen here – rifle discharger use. The cast iron cylinder ‘Battye’ bomb. A ‘Jam Tin’, or, to be pedantic, in this instance ‘Milk Tin’ bomb. (Author’s collection)

A battalion ‘Bombing Officer’ and an NCO per company were to be allotted to assist in training and to organize the supply and storage of grenades. In the cavalry the basic trained element was to be one NCO and four men per troop. To carry the numbers of grenades needed for bombing duels various forms of grenade waistcoat, bandolier, bag and ‘bomb bucket’ were introduced. Flaming grenade bombers badges were initially worn unofficially, and confirmed officially by an army order of 11 October 1915.

That month the ‘Grenadier Party’ had a revised complement of nine: an NCO in command; two bayonet men; two grenade throwers; two carriers and two spare men. The bayonet men were selected from ‘quick shots and good bayonet fighters’, and were specifically ordered to advance with magazines charged and a round ‘in the chamber’ to protect the bombers ‘at all costs’. The grenadiers were supposed to keep both hands free for throwing, and the carriers to keep closed up enough to pass the grenades or take the place of a wounded comrade. Spare men would carry up further supplies until required for other duties. As part of a bigger attack grenadier parties could follow one another, or be backed up by the remainder of their platoons, who would also carry grenades. Once an objective was reached it was thought best to drive the enemy an additional 50 yards to put him out of grenade range, and then establish two temporary barricades or blocks across the trench. The section of the trench wall between the two obstructions could then be pulled down to create a permanent block whilst the workers were covered by other members of the team.

By mid 1915 the powerful and distinctive side-levered Mills bomb (or ‘No 5’), which would become synonymous with Tommy in the trenches, had entered service. The Mills bomb was an impressive performer: tests confirmed that anybody within 10 yards of its explosion was well nigh certain to be hit by its fragments, and that between 10 and 20 yards away there was a fair chance of injury. At 25 yards there was still a one in four possibility that a target would be hit. Weekly demand for Mills bombs was prodigious and apt to fluctuate wildly due to the strategic situation: half a million were wanted every seven days in July 1915, with 1.4 million being demanded in August 1916. Naturally it would be some time before such ambitious production targets were achieved, so the British Army struggled through 1915 with a whole phalanx of less efficient grenades making up the numbers.

Amongst these were not only factory-produced improvements on the ‘Jam Tin’ and ‘Hairbrush’ but oddities such as the friction pull ‘Pitcher’; the ‘Lemon’, and the ‘No 15’ ball grenade. The Pitcher, light and heavy versions of which became known as the Nos ‘13’ and ‘14’, was widely accepted as one of the most unreliable and dangerous bombs of the war: even the official History of the Ministry of Munitions admitted that accidents were ‘so numerous that they won for bombers the name of “Suicide Club”’. The Lemon bombs, Nos ‘6’ and ‘7’ were not as bad, and were delivered in boxes of 40 together with four haversacks. However, not many were produced and to activate them required such a Herculean pull that sometimes it was like removing a cork from a bottle, or even needed the efforts of two men working together. The ‘No 15’ was produced in numbers, and was much like the ball grenades of yore. Frank Richards of the Royal Welch Fusiliers called it the ‘cricket ball’.1 It was effective enough, but only if well stored away from damp. It was a staple of combat as late as the battle of Loos.

Parallel developments took place amongst the Germans, and grenadiers had certainly commenced working in concert by January 1915. During the course of the year orders were issued that ‘all infantrymen and pioneers must be trained in bombing just as thoroughly as they are trained with the rifle’. Soon the Handgranatentrupp of half a dozen, or seven, men was being promoted for both offensive and defensive actions. In the attack the assault groups moved as small scattered parties, not lines, and entered the enemy works as swiftly as possible. Once there they rolled up the line, ‘bombing’ along the trench, throwing grenades over the traverses and forming ‘blocks’ using sandbags, shields, spades and anything else that members of the party carried with them. On the defence the Handgranatentrupp went into action immediately, and unbidden by higher authority, as was illustrated by orders issued to 235th Reserve Infantry in December 1915:

All men of the party carry their rifles slung, bayonets fixed and daggers ready, with the exception of the two leaders, who do not carry rifles. The latter may carry as many grenades as they can conveniently handle and should if possible be armed with pistols. The commander, similarly armed, follows the two leading men… The remaining three men follow the others one traverse to the rear; they keep within sight of their commander, and carry as many grenades as possible. When possible the grenades are carried in their boxes. The two leading men advance along the trench in a crouching posture, so that the commander can fire over them. The interval between traverses is crossed at a rush.

By early 1916 the Handgranatentrupp was further refined so that it comprised eight men plus a leader. The eight could be broken down into two subsections of four, with the lead portion of the Gruppe composed of two ‘throwers’, with two ‘carriers’ in support. When necessary all four threw grenades, creating short but heavy showers of bombs. The lead team carried daggers and pistols, the follow up rifles and bayonets plus fresh supplies of grenades and sandbags. To deal with a blockhouse or machine gun post two members of the team would adopt sniping positions, keeping down the heads of the defenders whilst the remainder worked their way around the objective using shell holes or any other handy cover. Finally they would rush the position from unexpected angles.

By the middle of the war many commanders on both sides were becoming concerned that their men had gone ‘bomb mad’ – by which they meant that they tended to use bombs rather than rifles even when the latter was obviously the correct choice. Injunctions were issued demanding that skills with the rifle should be strictly maintained. Being ‘bombed’ was an almost uniquely terrifying experience, and one which Lieutenant Symons of the 2/8th Worcesters barely survived when caught out in No Man’s Land just before dawn:

The first thing I knew about it was a rifle going off point blank and I turned round and cursed the sniper who was with me as I thought he had let off his rifle. As I turned I saw the earth at his feet kick up and then a bullet came at my feet and I looked and saw a Hun at handshake distance firing. Luckily they were either so flurried or such putrid shots that they did not hit us, anyway I was in a shell hole almost instantaneously. But the second I got in I saw a hand grenade just falling in my hole so I dashed off and got into another five yards further away. As I ran they threw six at me which burst in a shower all round and I felt my left hand go numb as I fell into the crater and when I looked at it there was only a red pulp with splinters of bones and tendons in it on the end of my arm… I got out my field dressing and poured iodine over the jelly and put on the dressings as well as I could and then bound my arm to my stick with my tie. As soon as this was done I ate my maps with all the HQs marked on them.2

Whilst grenades in the hands of small teams were the first weapons to find chinks in the tyranny of lines and trenches many devices were tried with greater or lesser success. Trench mortars, catapults and rifle grenades had all existed before 1914, and all developed rapidly during the first 18 months of the war. It was also true that all applied the same basic principle of lobbing a missile at high angle, so that it would fall into, rather than shoot across, defensive works. The rifle grenades of 1914 were based on a pattern devised by Englishman Frederick Marten Hale. The payload of the bomb and its detonator were contained in a cylinder on the end of a rod. The rod was slid into the barrel of the service rifle, which was loaded with a special blank cartridge. Any safety device, such as a pin, was withdrawn, and the rifle fired at high angle. The pressure behind the rod forced the grenade out of the rifle at speed and the grenade shot off towards the enemy. Being nose heavy the end bearing the percussion device hit the ground first and exploded the grenade. The German rifle grenades were the models 1913 and 1914 and the main British type the ‘J’ Pattern, later known as the ‘No 3’. Though such grenades were fairly local in their effects the impact could be increased by firing them off in volleys, perhaps from stands set to predetermined angles within the trench system. The ‘No 3’ was powerful enough to dissolve into a cloud of fragments on detonation likely to cause serious injury or death to anyone within a circle 10 feet in diameter, and quite a few injuries well beyond that range. Many other rodded designs, adapted for greater simplicity and ease of use, followed.

By 1916 Mills bombs were adapted for rifle projection, first with the addition of a rod, and finally by means of a cylindrical ‘discharger’. The French, Germans and Americans all adopted rifle grenades projected from dischargers or cups later in the war. The French model, also used by US forces, was the ‘Vivien Bessière’. Named after its inventors, Jean Vivien and Gustave Bessière, it was a small grenade fired from a muzzle attachment or ‘tromblon’. The cartridge used to launch the bomb was a bulleted round which passed through a channel in the grenade and ignited its fuse as it was launched. Though it was not adopted by the British Army the ‘VB’ grenade received its UK patent in January 1916. The German Wurfgranate of the late war period worked on the same principles.

The mortar was a weapon of surprising antiquity, having been in existence, primarily for siege operations, since about 1500. Interest in the development of modern ‘trench mortars’ stemmed from the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 and the battle for Port Arthur. It was the Germans who were most alert to the possibilities, noting how mortars might be applied to French fortifications in the future. A specification was therefore issued for the development of a Minenwerfer throwing a demolition charge of 110lb or greater; capable of accurate fire to at least 330 yards; plus combining compactness with the least possible weight. The first heavy trench mortars were deployed with German pioneers in 1910. Despite this lead even the Germans could field only 190 weapons at the outbreak of war. The result was the rapid development and deployment of several different stopgap mortars. These included the so-called ‘Earth Mortar’ which was a tube buried in the ground for lobbing a 52lb sheet steel projectile; the Albrecht with its wooden tube made in three calibres, and the Iko Flügelminenwerfer. The Iko was a particularly unwieldy smooth-bored beast with a massive base plate, throwing a 220lb projectile about 1,090 yards. At the other end of the scale was the little Lanz mortar capable of projecting 9lb shells about 440 yards.

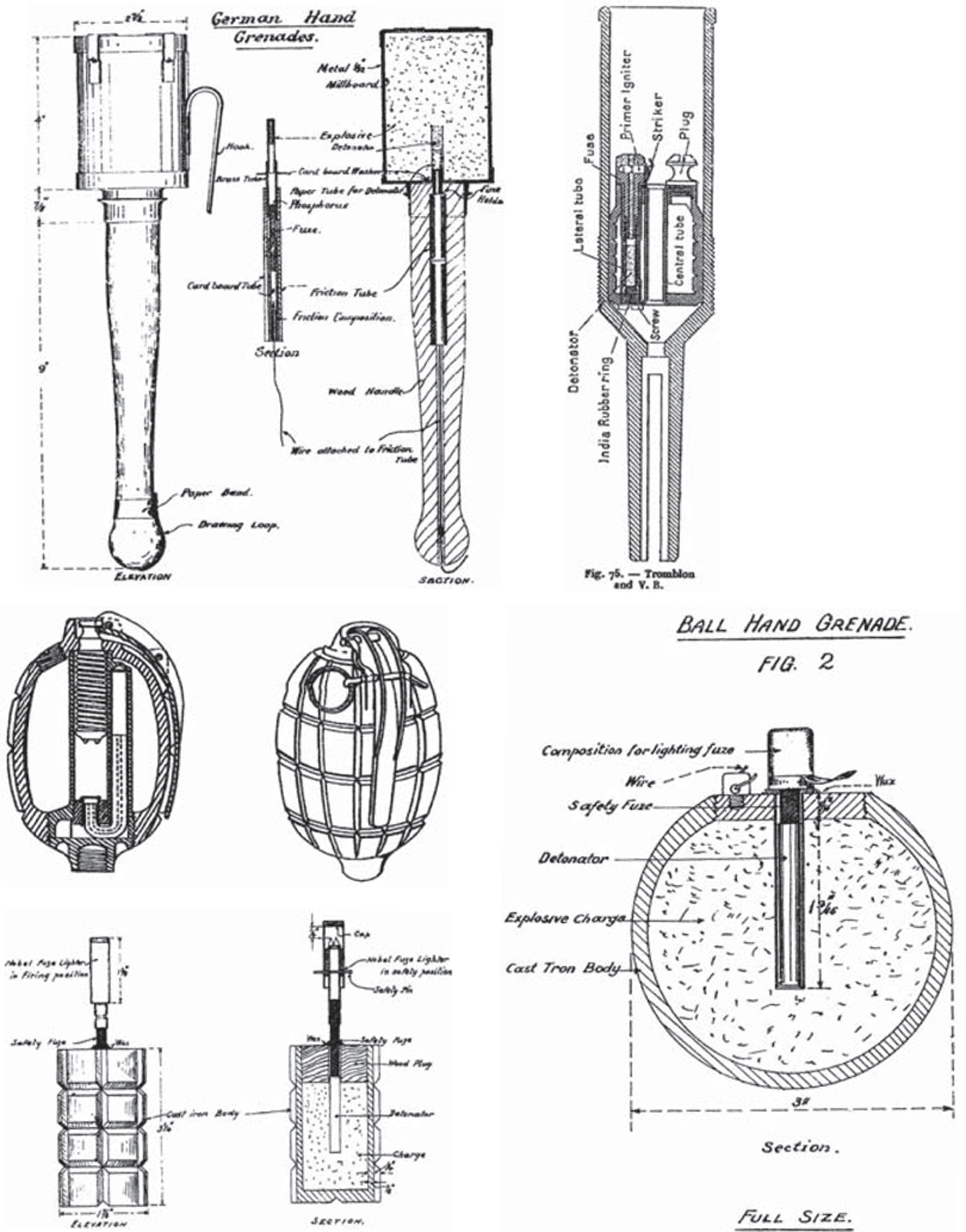

From the Australian Grenades and their Uses, 1916, showing a diagram of the West spring gun. (Author’s collection)

Being on the receiving end of ‘Minnie’ fire was a terrifying and occasionally surreal experience. The mortar was usually concealed in a pit, and the sound of its discharge was less impressive than the bark or roar of ordinary artillery. The bombs were predominantly large but, being projected at high trajectories and relatively low velocities, could sometimes be seen tumbling or wobbling towards the ground through a serene arc. The blast created by large missiles was prodigious. Captain Hitchcock recalled that one blew his candle out, even in a dugout 20 feet below ground. For destroying all but deep dugouts and collapsing sections of trench nothing but the heaviest artillery could equal the effect. As George Coppard of the Machine Gun Corps recalled, ‘men just disappeared and no one saw them go’.3

German soldier Karl Josenhans was uncomfortably close as he watched Minenwerfer bombs fall onto the French lines:

One murderous instrument with which we have the advantage is the big trench mortar. They hurl huge shells about a thousand feet into the air and they fall almost vertically… Earth and branches are flung into the air to the height of a house, and although the shells fell 80 yards away from us, the ground under us shook. During the explosions I was looking through a periscope into the French trench opposite and could see terrified men running away to the rear. But somebody was evidently standing behind them with a revolver, for one after another they came crawling back again. This war is simply a matter of hounding men to death, and that is a degrading business.4

By 1916 German efforts focused on three standard models: a light 7.5cm, medium 17cm and heavy 25cm mortar. The following year it proved possible to replace whatever mortars were then held by the infantry with four ‘new model’ 7.5cm light Minenwerfer per battalion. All were capable of being shifted in wheeled carriages, though trench conditions meant that they were often dismantled and carried in pieces. In 1917 the light model Minenwerfer was also fitted with a flat trajectory carriage that allowed it to be used as a close support weapon, or even an anti-tank piece.

British trench mortars got off to a comparatively slow start, and not until October 1914 did Field Marshal French make a specific request for ‘some special form of artillery’ suitable for trench destruction. So it was that the British struggled for almost a year with inadequate numbers of inefficient, and often dangerous, stopgaps. The 5inch ‘Trench Howitzer’ that materialized in December was dismissed as both unwieldy and inaccurate, and a better Vickers Pattern, accepted in March 1915, was available only in pitiful numbers. Such efforts were supplemented by obsolete 19th-century French mortars, and some fashioned locally from piping.

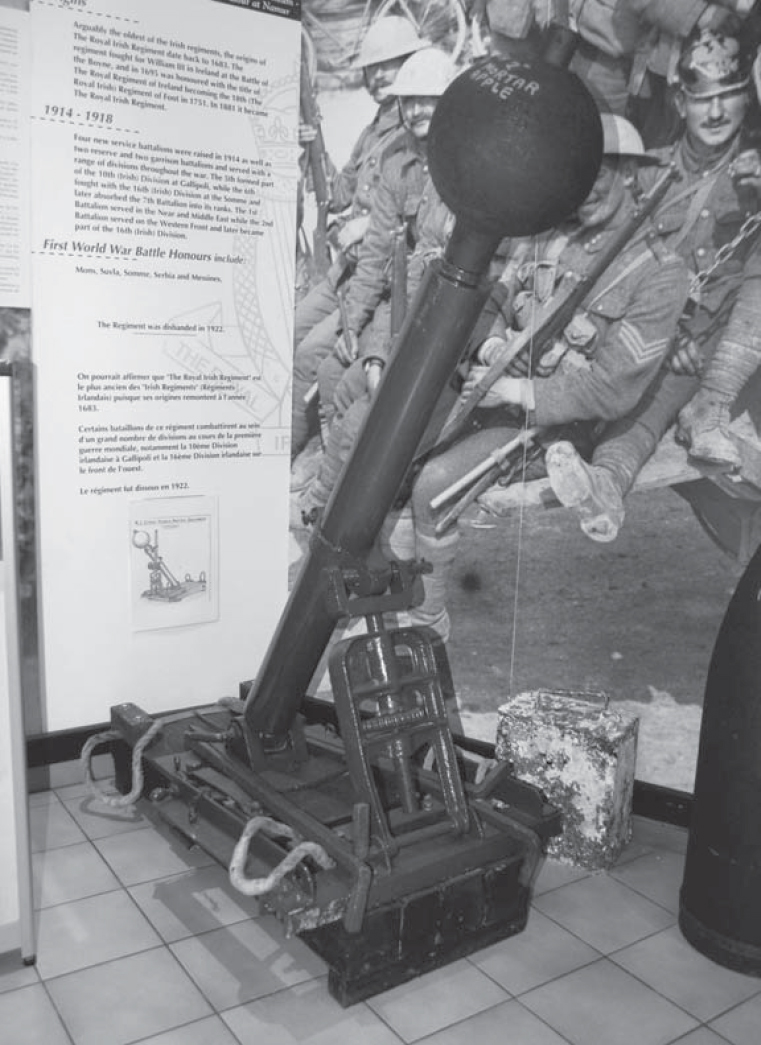

Dramatic improvements commenced in mid 1915 with the first arrivals of the 2inch ‘Trench Howitzer’, colloquially known as the ‘Toffee Apple’ bomb-thrower. True to its nickname the key to the weapon was its projectile, a large spherical bomb mounted on a steel ‘stick’. The bomb weighed 50lb and could be thrown 500 yards. By the time of the offensive on the Somme about 800 of these mortars were in use. An interesting refinement seen on some of them was a periscope attachment that enabled the firer to see the target from within the safety of a pit. A devastating salvo of Toffee Apples was witnessed by Wyn Griffith of the Royal Welch Fusiliers:

A pop, and then a black ball went soaring up, spinning round as it went through the air slowly; more pops and more queer birds against the sky. A stutter of terrific detonations seemed to shake the air and the ground, sandbags and bits of timber sailed up slowly, and fell in a calm deliberate way. In the silence that followed the explosions, an angry voice called out in English, across No Man’s Land, ‘You bloody Welsh Murderers’.5

Ammunition for the 2inch trench mortar, or ‘Toffee Apple’ bomb thrower, being brought up on the Somme, Acheux, 28 June 1916. The projectile heads are seen being picked up from the large dump and carried on blocks with a harness across a waterlogged ditch, which has been bridged using wooden 18pdr ammunition boxes. The metal projectile ‘sticks’ or tails were fitted to the explosive heads prior to firing. (IWM Q747)

At the end of 1915 the French 9.45inch heavy ‘flying pig’ design was also added to the British inventory. Parallel work in the UK also led to the development of the remarkable Stokes mortar, brainchild of Wilfrid Stokes of Ipswich. The Stokes was simple, consisting essentially of a barrel and pair of legs, and a bomb that slid into the mortar tail first. It met four vital criteria: simplicity, speed, lightness and ease of setting up. Despite teething difficulties it was introduced in 1916, and within a year had proved its efficiency. Its basic design has informed that of mortars the world over, ever since.

The trench mortars of both friend and foe were distinctly unloved by the front line infantryman, not least because one of their most favoured tactics was to displace before any retaliation occurred. As C. J. Arthur put it:

The trench mortar batteries used to come up and let off a few rounds, then go back. We were left to patch up the trenches after the usual replies from the ‘minnie’ brigade. Those Minenwerfers! I shall never forget their soul-destroying qualities. To be hit by something you could not see was not too bad, but to see something coming, sufficient to blow a crater of 15 feet diameter and not know which way to go to avoid it, was enough to destroy the nerve of a suit of armour. You can imagine, therefore, how decidedly unpopular the trench mortar batteries became.6

It is perhaps surprising that the catapult, siege weapon of the ancients, should have gained a new lease of life early in World War I. That it did was due at least in part to the early lack of more modern equipments such as mortars and rifle grenades. Like the ancient weapons many of the new catapults worked on two basic principles – the sprung arm and the bow. One built by the Cambridgeshire Regiment in Ploegsteert Wood was indeed a direct copy of a Roman machine, inspired by the classical scholarship of a Cambridge professor. A few others depended on elasticity, being not unlike overgrown schoolboys’ catapults. Most threw some form of grenade, or an extemporized Jam Tin. In addition to being relatively easy to produce these catapults had the not inconsiderable advantage of being comparatively quiet. Conversely they were not always easy to mount and conceal, had relatively short range, and were quickly outclassed by better weapons. In British official nomenclature they were ‘Bomb Engines’; in the German, Wurfmaschinen, or ‘Throwing Engines’.

Some catapults were local improvisations or patented inventions that never got much beyond the experimental. Various French devices using the leaf springs of lorries and assortments of bicycle parts would seem to conform to these descriptions. Nevertheless certain types saw widespread use. Amongst these were the French Sauterelle, and the Leach catapault and West spring gun in British service. The Leach, devised by C. P. Leach of South Kensington in 1914, was a large fork, rubber springs and a sling to hold the projectile. It was also known as the ‘Gamage’s’ catapult, since the famous London store was co-patentee, and the production version of the device was built in their factory. Amazingly Leach catapults were issued on a scale of 20 per division in 1915.

The West spring gun, issued on the same scale as the Leach, relied on an arm whose vicious forward and upward flick was powered by a battery of steel springs. Downward pressure on a cocking leaver by two or three men set the mechanism. It could be carried into position by stretcher-like handles, and required sandbags on its base to prevent it bucking crazily on discharge. Guy Chapman thought that the West was likely to decapitate its user, and its dangerous reputation was certainly confirmed by a November 1915 report in the 144th Brigade War Diary:

Lieutenant Schwalm, 6th Glosters, Brigade Grenadier Officer, was killed whilst firing the West bomb thrower, his foot slipped and his head was hit by the arm of the machine, after the spring had been released. This is not the first accident which has occurred with this machine, a very cumbersome one from which the results obtained are no means commensurate with the dangers incurred by the user and the difficulty in manoeuvring it.

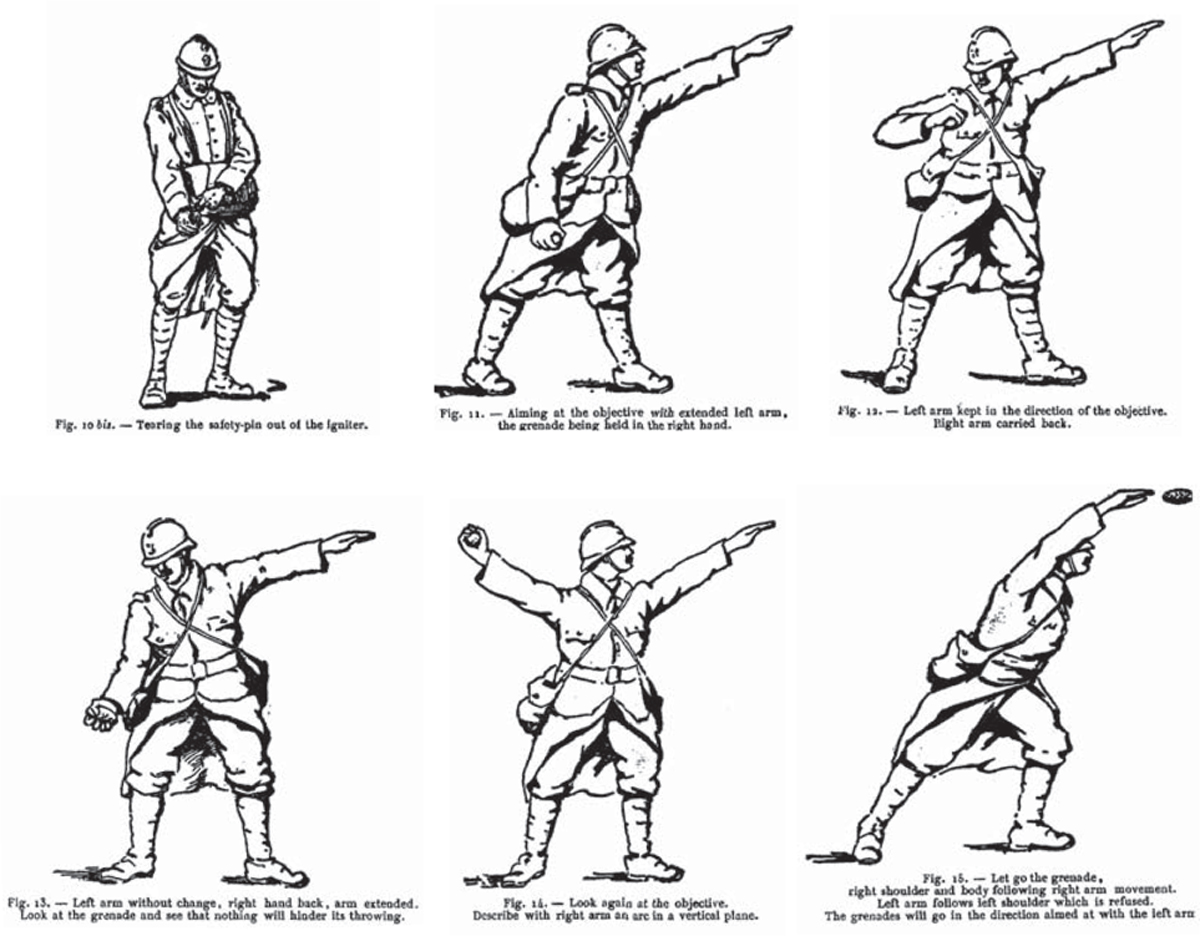

A series of drawings from the French Platoon Leader’s Manual, 1917 showing a grenade throwing sequence. (Author’s collection)

Experimentation with the weird and wonderful continued even after the demise of the West and Leach. In June 1916, for example, the Munitions Design Committee looked at a ‘Rotary Apparatus for Throwing Grenades’ designed by a Sergeant Day. This operated on the centrifugal principle, and once cranked up to speed the user consulted a ‘speedometer’ which indicated how far the bomb would fly on release. Though the machine was deemed portable, and a test determined that grenades could be flung fairly accurately to 150 yards, it was decided that the weapon was ‘unsuited to the service’. Another eight-armed centrifugal device designed by a Mr Bonnafous was also rejected by the same sitting of the Committee.

Flame weapons had existed since classical times – but a portable, practical, device for the battlefield had only been perfected in Germany in the years leading up to war. The first Flammenwerfer attack was made against the French at Malancourt in February 1915.

Before long ‘liquid fire’ was also turned on the British at Hooge. In part the flamethrower was a terror weapon – since it was very short range and for many it was totally demoralizing – but not all were daunted. Captain Hitchcock reported that the Leinsters were taught to aim specifically at those carrying the Flammenwerfer tanks, who had a heavy burden to carry, and could on occasion ignite with ‘a colossal burst’. Later the 2nd Royal Welch Fusiliers were treated to a demonstration with a captured flame-thrower, which they found more amusing than expected because, ‘its premature operation scorched some of the staff’. An eyewitness of a flame attack was Guy Chapman at Third Ypres:

The enemy were attacking under cover of Flammenwerfer, hose pipes leading to petrol tanks carried on the backs of men. When the nozzles were lighted, they threw out a roaring, hissing flame 20 or 30 feet long, swelling at the end to an oily rose, 6 feet in diameter. Under protection of these hideous weapons, the enemy surrounded the advance pillbox, stormed it and killed the garrison.7

Remarkably the German flame attack soon generated its own very specific modus operandi. As outlined in late 1915 the textbook assault began with the blowing of charges to create holes in the barbed wire, then on the sound of a siren or whistle the discharge of large static flame-throwers. The conflagration from these fixed devices was vicious, but lasted only a minute, at the end of which the attackers would swarm from their trenches – often up short ladders that had been specially positioned. Taught that small amounts of burning fuel left on the ground posed no serious threat they would hurry on before the defenders had a chance to react. The first wave were the ‘assaulting party’ with man pack flame-throwers,8 grenades, rifles with fixed bayonets and engineers with charges for blowing strong points or stubborn wire. The men would be dressed in ‘assault order’, and have with them at least two grenades and 200 rounds of ammunition. These were followed by a ‘consolidating party’ whose job was to hold the trenches captured. In the rear followed a ‘carrying party’, to bring up grenades, ammunition and other stores, and the ‘communication trench construction party’ whose much longer and laborious task was to connect the works captured with existing saps. As the attack unfolded artillery and mortars would open fire, shelling selected positions – thus supporting the assault as it unfolded rather than giving the enemy prior warning. Captain P. Christison of 6th Cameron Highlanders faced the peril of the flame-thrower at Passchendaele:

There was no immediate counter-attack, but towards dusk one came in – headed by flame-throwers to add to our misery. This was a new one. Our rifles and light machine guns were now useless, being gummed up with mud, and we had to hurl grenades and use pick handles in close combat. One had no time to feel frightened it all happened so quickly. I saw a large Hun about to aim his flame-thrower in my direction and Company Sergeant Major Adams with great presence of mind fired his Verey pistol at the man… The round hit the flame-thrower and with a scream the man collapsed in a sheet of flame.9

In terms of producing flame weapons the Allied response was patchy. Arguably the French learned the techniques most quickly, and a patent for a French portable flamethrower was lodged by March 1915. The British concentrated on fixed flame projectors. An American devised a bizarre ‘flaming bayonet’, which, perhaps fortunately, appears never to have reached the battlefield. As so often happened response then met with counter-response as the Germans issued instructions that their own artillery should be concentrated wherever possible on enemy flame projectors, whilst the infantry focused on attempting ‘to shoot the men carrying the small apparatus’, whose dangerous burdens would then become a hindrance to the men around them.

An MG 08 deployed on an improvised wooden based ‘trench mount’, 1917. The standard mount of the MG 08 weighed 70lb – not counting any armoured shield, cooling water, spare barrel or ammunition. Attempts to increase battlefield mobility led to the use of many different lightweight mounts, and eventually the introduction of a tripod, though this was never a universal issue. Finally the ‘08’ was replaced in the attack by the somewhat lighter 08/15 with shoulder stock and bipod. This team, wearing 1915 type gas masks, are led by an NCO (right) with the oval arm badge of the MG ‘Sharpshooter’ detachments. These independent Scharfschützen units were allocated wherever circumstance demanded rather than permanently tied to an individual infantry regiment or battalion. (Author’s collection)

Perhaps more than anything it was the development of the light machine gun that helped free the infantry from pedestrian tactics – and whilst the Germans could claim leads in the fields of the grenade, mortar, light weight artillery and flame-thrower the British had a definitive head start in this area. The Lewis gun, initially referred to by some as an ‘automatic rifle’, was first designed by an American before the war and was under production in Birmingham by August 1914. It weighed about 29lb, against the 90lb of Vickers gun and tripod. The immediate priority was that the air-cooled Lewis should be adapted for use for aircraft, but before the year was out demand for machine weapons of any type – and a growing realization that lightness had advantages – saw its experimental introduction with the infantry. A gradual build up in Lewis gun numbers allowed the heavy Vickers guns to be withdrawn from the infantry and placed together into the companies of the Machine Gun Corps, which was founded in October 1915. Thereafter Lewis gun numbers continued to increase in the ranks of the infantry, to two per company by the Somme, and to at least one per platoon during 1917.

Whilst it had long been realized that Lewis guns had greater flexibility to be hidden or rapidly redeployed in and around the front line trenches, and the long range of the Vickers suited it better to flanks or positions further back, the organizational separation of the two hastened tactical reassessment. A key instruction in this development was Notes on the Tactical Employment of Machine Guns and Lewis Guns, issued in March 1916. This drew a clear distinction in tactical roles. Lewis guns complemented heavier machine guns, but could not entirely replace them, nevertheless:

Owing to its lightness and the small target that it offers, the Lewis gun is of great value in an attack. It is particularly adapted for providing covering fire from the front during the first stage of an attack. Lewis gunners, under cover of darkness, smoke, or artillery bombardment, may be able to creep out in front and establish themselves in shell holes, ditches, crops, long grass etc., where it will be difficult for them to be detected, and where they will be able to fire on enemy machine gun emplacements, loopholes and parapets generally, and so assist the infantry to advance. Covering fire on the flanks of the attack, must, however, be provided by machine guns as they can keep up a sustained fire from stationary platforms on previously considered objectives.

A selection of automatic weapons from the trenches. Left to right: German 08/15 light machine gun; Bergman ‘MP 18’ Maschinenpistole; British Lewis gun; and French Chauchat model 1915 or ‘CSRG’ machine rifle. The MP 18 was the first true sub-machine gun, firing a 9mm pistol type round from a 32-round magazine. Designed for trench clearance and mobile attack it came too late to have a significant impact on events. (Author’s collection)

At this stage, however, it was thought that Lewis guns should not be in the forefront of the attack proper – an opinion that was later modified.

The withdrawal of the Vickers guns from the infantry to the companies of the Machine Gun Corps was not met with universal approval, but this mass of heavy firepower did allow more imaginative long-range saturation tactics. Machine gun ‘barrage fire’ was defined by The Employment of Machine Guns, Part 2 as, ‘the fire of a large number of guns acting under centralised control, directed on to definite lines or areas, in which the frontage engaged by a gun approximates [to] 40 yards’. Commonly guns would be concentrated in ‘batteries’ of from four to eight machine guns, and anything up to 24 guns in several batteries would make up a ‘group’. The wall of bullets thus generated could be used for a number of different purposes: preventing enemy troop and supply movements; destroying morale; preventing the operation of working parties; creating a protective screen of fire; general harassing, or suppressing enemy fire. Machine gun barrages could also supplement artillery barrages, being worked progressively over areas or adding a surprise element at intervals. By regulation a ‘slow’ barrage was 60–75 rounds per minute per gun (in bursts of 15–25 rounds); ‘medium’ 125–150rpm; and ‘rapid’ 250–300rpm. It may thus be seen that a full size group firing a ‘rapid barrage’ was capable of dropping over 7,000 rounds per minute into a relatively confined space.

Interestingly, the French had quickly come to the conclusion that light machine weapons would be useful for ‘walking fire’, in which a two-man team could fire on the move – or rather more practically go prone from time to time during the advance. Unfortunately it was some time before the 1915 model French Chauchat could be made in quantity, and worse, the gun itself proved unreliable, unergonomic and intolerant of mud. The concept of carrying light machine guns into the forefront of the attack remained, however, and sooner or later all the major armies included a sling with their weapons.

The German MG 08/15 light machine gun was much more reliable than the Chauchat, but also took time to bring into production, and was actually quite weighty at 43lb. As Georg Bucher recalled:

I wasn’t at all enthusiastic about that latest type of gun – in the first place I was unable, with the best will in the world, to understand why the clumsy things should be called ‘light’, and secondly, the old heavy gun was my favourite weapon because of its reliability and precision.10

Nevertheless the introduction of the 08/15 was one of the things that allowed the German infantry to adopt more flexible ‘self supporting’ tactics in the latter part of the war. German Sixth Army instructions on the use of the new gun recommended three-man teams, who were to carry carbines for close protection, or in the event of mechanical failure of the machine gun. Initially it was intended that the weapon be positioned near to the platoon commander, and that the battalion commander keep a reserve of these guns in hand for use in counter-attacks. Ideally the 08/15s, which were highly suitable for flanking fire, were to be ‘posted in the first line, in shell craters, or in other available places which have been reconnoitred in advance’. Where possible two different guns were to be able to cover one piece of ground. As the 08/15 was not suitable for overhead fire direct lines of sight to the targets were needed, but it was ideal for ‘mobile defence’ and bursts of ‘harassing fire’ in short surprise volleys.

German MG 08/15 team. Devised in 1915, but not reaching the front in large numbers until 1917, the new ‘light’ machine gun was still water-cooled, belt fed, and weighed about 43lb. Nevertheless its widespread issue down to small unit level made possible much more flexible tactics in which machine gun support could be carried forward at the pace of the infantry platoon. Note the use of the weapon’s distinctive wooden shoulder stock and the 250-round metal ammunition boxes shown here. Some guns were fitted with a detachable drum magazine. (Author’s collection)

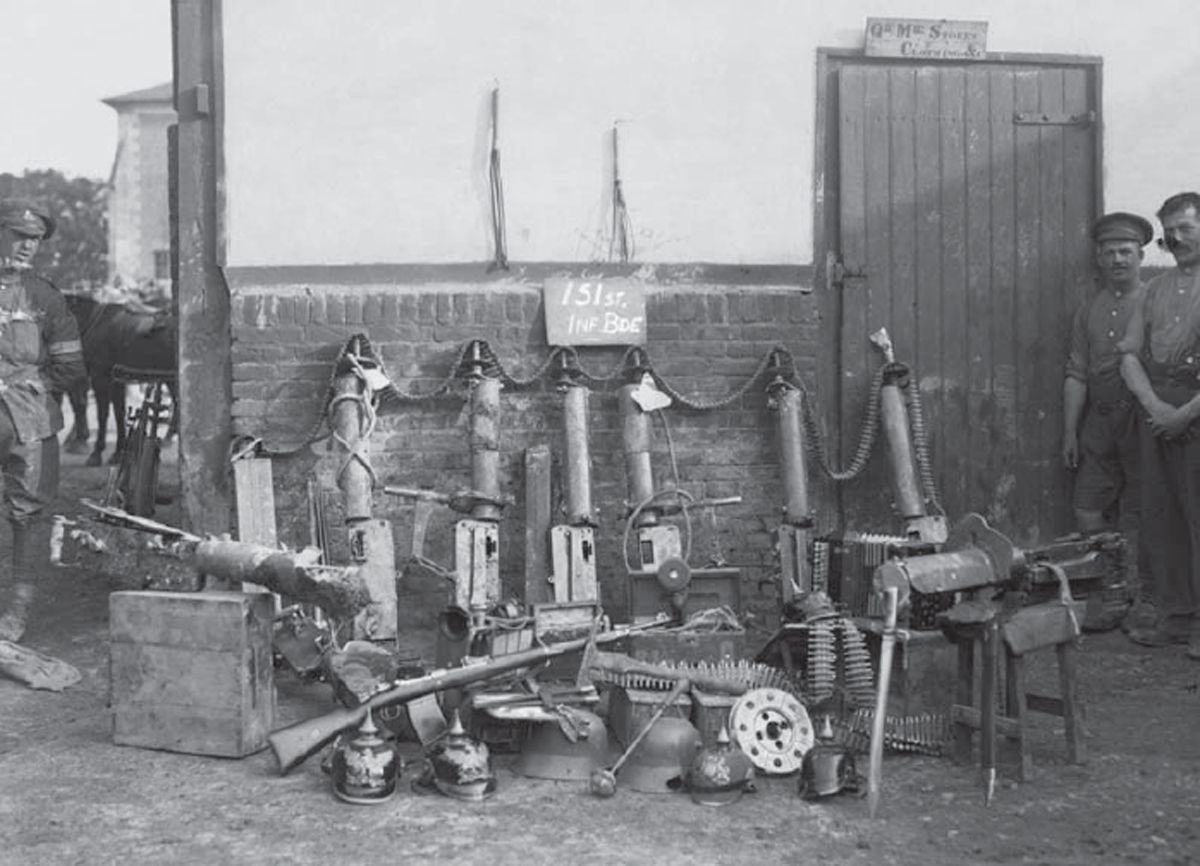

German booty captured by the South Staffordshire Regiment on the Somme. The weaponry includes nine MG 08 machine guns, a bayonet and a G98 rifle with special 20-round ‘trench magazine’. Towards the centre are boxes of communications equipment. In the foreground are spiked helmets or Pickelhauben from Baden and Bavarian units; steel helmets; and a trench club. (IWM Q162)

As the German manual observed:

It should not be forgotten, however, that the precision of the 08/15 machine gun is limited and that this fact must be taken into account in regulating and utilisation. The gun must never completely take the place of infantry, but on the contrary, the infantry must have clearly in mind that for them the 08/15 machine gun is only a means of increasing their firing capacity. By reasons of imperfections of a technical order the 08/15 model does not serve entirely to replace the 1908 machine gun.

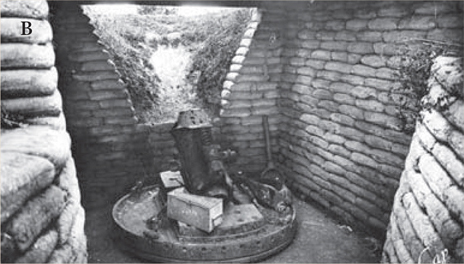

The archaeology of a mortar pit: Vimy Ridge.

On the battlefields of the Western Front, even those now preserved as memorial parks, trenches and shell holes can often appear as surprisingly gentle or shallow features. In some areas this may be because of high water tables which impeded deep excavations – but more usually it is due to ‘solifluction’, or soil flow. Observed over time soil may act more akin to a liquid than a solid, creeping to restore uniform levels. This phenomenon is more pronounced, and may occur more rapidly, in sandy or muddy conditions – indeed, geomorphologists commonly divide movement into ‘wet mud flow’, and ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ sand flow. The following illustrations show such effects on a German mortar position constructed according to standard plans.

A) Mortar position schematic from the latter half of the war. The oblong cavity is framed with timber and accessed from the rear by five steps down. Overhead cover is of a sandwich construction, which includes baulks of wood, concrete and sand. This arrangement is designed to burst shells before they can penetrate the pit and absorb shock and fragments. The high angle of outgoing fire means that the embrasure is effectively a large, steeply sloping slot in the ground, presenting no direct target to the enemy. (Author’s collection)

B) Inter-war photo of a preserved sandbagged pit within the Canadian memorial park at Vimy, c.1930. A medium Minenwerfer, together with its accoutrements and a helmet, is correctly positioned with a circular traversing base on the floor of the pit, its muzzle pointing up through the steeply sloping port. However, soil flow has already commenced, as can be seen from the vegetation pattern. (Author’s collection)

C) Author’s photo showing the same structure in 1988. Over just half a century almost a foot of soil has flowed in through the aperture, burying the weapon so that the deep base plate is now flush with the ground level. The lintel over the pit embrasure, some of the cement sandbags, and all the small artefacts, have disappeared whilst the mortar has been broken from its mount. Rather than re-excavation to conserve the monument poor restoration techniques have included blocking up the embrasure with an additional three courses of sandbags in a vain effort to prevent flow, and the placing of an anachronistic concrete ‘duckboard’ to keep visitors’ feet clear of the mud. The impression created is of a very shallow concrete bagged pit, quite unlike the original. (Author’s collection)

D) Contemporary photo showing how the medium Minenwerfer was disassembled for movement over rough terrain, with the heavy barrel slung between four of the crew. (IWM Q23723)

E) An extemporized battlefield variation on the textbook mortar pit showing how the medium Minenwerfer was muzzle loaded, an operation requiring particular care as the barrel was rifled, and the shell weighed 110lb. It could be fired at a maximum speed of one round per minute. The range of the 17cm medium Minenwerfer was about 985 yards, and the projectiles included high explosive and gas munitions. According to Notes on German Shells, 1918, explosive rounds of this calibre were likely to create shell holes 5 feet deep and almost 10 feet across in clay; even larger holes were blown in other types of soil. (IWM Q56544)

The initial American approach was summed up by the document Notes on the Use of Machine Guns in Trench Warfare, issued in March 1917:

In trench warfare as it exists in Europe, automatic machine rifles, popularly called machine guns, find their greatest use. Besides the trench, the essential elements of the trench line consist of a depth of wire and a front of machine guns. The tremendous stopping power of machine guns enable them to replace a large number of riflemen along this line, reducing to a minimum the men employed in actual defence, thereby leaving a large part of the force in reserve for use in the counter-attack, or for the assumption of the offensive at another part of the line. Their use also reduces the daily wastage due to sickness, and prevents the offensive spirit of the infantry from becoming impaired.

Somewhat optimistically this manual claimed that the US Benet-Mercie model 1909 gun could fulfil all of the roles of both the machine gun proper and the machine rifle. Sadly this proved to be an exaggeration of its capabilities, and in fact American forces used a number of different types of machine gun depending on availability and which ally they were fighting alongside.

The German 7.6cm ‘new type’ light Minenwerfer. This rifled mortar fired a 11lb shell to a range of over half a mile, and could be used with both high explosive and gas munitions. At the beginning of 1917 four of these weapons were directly attached to each infantry battalion, replacing obsolete models and providing immediate fire support. Pictured in September 1918 with men of a Landsturm infantry unit this mortar is in a low-trajectory mounting on a wheeled travelling carriage. (Author’s collection)

British 2inch ‘Trench Howitzer’ or ‘Toffee Apple’ bomb thrower in the visitor centre at the Ulster Tower, Thiepval. A suitable riposte to the German Minenwerfer, the Trench Howitzer packed a heavy punch. During the Somme these weapons were in positions just a few hundred yards from this display example. (Author’s collection)

American instructions took particular note of the painful lessons that had been learned in offensives prior to 1917:

Experience in Europe has been that some machine guns and crews have always survived, ready to emerge and open a flanking, annihilating fire against the enemy’s advancing infantry and the more oblique has been this cross fire the greater has been its effect… Emplacements in front of the firing line are made by digging narrow trenches of the same depth as the firing trench to the front, 15 or 20 feet, and then turning them to the right or left and then widening them out to accommodate the guns and crews. The gun rests solidly on the ground at the end of this cul de sac, which is sunk just low enough below the natural ground to conceal it when in position… Where opposing trenches are close together and machine guns would be subject to capture by raid if placed in the front line trench or in front of it, this danger can be avoided by emplacing them behind the parados of the firing trench. This position will give a better field of fire, and, owing to the feeling of safety which this position inspires, the men will work their gun with more coolness and judgement than if the gun were sited in the parapet or in front of it.

Though it was appreciated that the machine gun officer was required to handle gun with ‘boldness and cunning’, US instructions did not immediately recognize that automatic weapons had a role in the spearhead of the attack. The initial theory was that machine weapons should be in the ‘fourth wave’. When moving forward it was stated that ‘the machine guns should mix with the infantry and try to disguise their identity as much as possible’. Combat experience and acquaintance with the woeful Chauchat made many in the US Army realize that both equipment and tactics needed swift and drastic revision. If anything the later American version of the French automatic rifle was worse than the original since it was modified to fire the more powerful .30 cartridge. This, and rushed production, tested the already dubious Chauchat beyond its capabilities. However, at the eleventh hour, and in a complete reversal of fortune, US forces received what was arguably one of the best light support weapons, the Browning automatic rifle, or ‘BAR’. Weighing 22lb it was lighter than the Lewis gun, and fired from a modern-looking 20-round box magazine. It has been criticized for production problems and lack of great accuracy, but this was not the point – it was capable of going where platoons and squads went, at much the same speed, and when it arrived in the summer of 1918 it was more than a match for anything else used in this role.