Sniper of the London Irish Rifles, Albert, August 1918. Equipped with an SMLE rifle with offset scope, he also wears trousers cut down to shorts. This particular patrol was a disaster: of seven taking part one was killed and three wounded. (IWM Q6902)

Trench raids were first attempted at a surprisingly early stage, and the British Official History claims that the first mounted by British troops took place on the Aisne on 4 October 1914, just east of Troyon factory road. Here the enemy had dug a sap, and it was decided that this should be seized and destroyed by a party of the 1st Coldstream Guards under Lieutenant Beckwith Smith. The guardsmen rushed across a hundred yards of No Man’s Land, and took two lines of trenches at bayonet point, but belatedly discovered yet another trench giving covering fire, so it was not possible to fulfil the objective. A wounded Beckwith Smith received the DSO. According to Corporal Sidney Amatt of the London Rifle Brigade some of the earliest German stealth techniques were almost laughably simple:

They would pick out big, strong, physically fit men and arm them with clubs – long handled clubs about twice as long as policemen’s truncheons and with weighted ends. They would black out their faces and crawl through our wire. Then, without making any noise at all, two of them would bodily lift out one of our sentries … and drag him over to their lines. When we got wise to that sort of thing we doubled the sentries.1

By early 1915 all parties were frustrated by lack of progress, fearful of poor morale, and often suspicious of enemy plans. As a result, and perhaps in some instances as a substitute for full-scale offensive action, raids and patrols became increasingly frequent and more organized. Small patrols might include a single officer accompanied by anything from one to half a dozen other ranks. Typical objectives included intelligence on enemy wire, troops and reliefs, or, more aggressively, the capture of an enemy patrol or the recovery of identification discs. Some raids were larger, as was that mounted by 2nd Royal Welch Fusiliers on 12 March 1915:

After the word had been passed down the Cameronian companies that a party of RWF was going out, we crept over at 10 o’clock in two parties; Lieutenant Mostyn, myself and ten men of ‘D’ Company in one party, Lieutenant Fletcher and 11 other ranks of ‘B’ were the other, 10 yards on our left. Approaching the German line we ran into a known listening post. The two, perhaps three, occupants, fired, but when we made a rush for them they hopped it and got away. We pushed on to their line. Fletcher spoke in German to try to put the garrison off, telling them we were Germans, but they were ready for us when we started bombing. There was nothing for it but to get back as best we could. A blast of Mostyn’s whistle broke off the action, and a flash of his torch let Hill know. Again we were between two fires, and our guns were barraging our flanks at 50 yards distance – as Mostyn insisted, for the gunners wanted it to be 100 yards.2

Scurrying and worming their way back guided by lamps in the British trench the raiders came under heavy fire; one man was lost and five wounded – not a few ‘left pieces of clothing and flesh on the wire’.

A party of the 1st/8th (Irish) Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment, on 18 April 1916. One officer, centre, is wearing a pullover, balaclava, gloves and face blacking and is carrying a revolver. Many of the men have soft caps and rifles with fixed bayonets or trench clubs. Other headgear shown includes captured Prussian spiked helmets and a service dress cap turned backwards. Turning the cap backwards had several useful effects during night raids: there was no peak to obscure vision; the cap was less likely to be knocked off; and from the front the general appearance was more like the German peakless Feldmütze. (IWM Q510)

As one officer bitterly remarked, this raid – and not a few like it – achieved little, because little was aimed at. Nevertheless early raids did build up experience, contribute to the development of minor tactics, and create a repertoire of clothing and equipment suitable for night and close combat. Gradually a blackened face, cap turned backwards, and rifle with fixed bayonet were supplemented by grenades, revolvers, trench daggers, coshes, knobkerries, knuckle-dusters, pullovers and muffled boots. The Royal Welch Fusiliers added the nice touch of knee protectors cut from old socks, and, on occasion, bill hooks as the raiding weapon of choice.

By the latter part of 1915 it was generally expected that each brigade would mount some sort of patrol every night. Instructions of 124th Brigade reminded its officers that patrolling and constant observation of the enemy line were ‘the best security against attack’. Patrols would therefore take particular trouble to investigate the enemy wire to ensure that no gaps had been cut ready for troops to move through. Likewise friendly wire and parapets were to be checked for security. The usual method to find men in this brigade was to identify a company, then make up two small patrols of an NCO and three men each. These four-man patrols would go out sequentially, thereby ensuring some kind of patrol activity over a protracted period. The patrols were to cross the friendly obstacle zone by means of ‘two or more zig-zag paths’ through the wire. On returning the patrols were instructed to halt outside the wire, whilst the patrol commander advanced to be challenged by the sentry guarding the entrance. Once identified the leader would bring his men through the gap.

A big raid chosen as the ideal model for future action was that by 5th and 7th Canadian battalions on the Douvre River on 16 November 1915. The raiders comprised two 70-man groups, and within each were sections devoted to different tasks, as for example wire cutting, bombing, blocking, supporting and reserve. Artillery co-operation on the day of the raid included targeting known enemy machine gun posts and wire. Despite minute preparation one of the Canadian groups drew fire prematurely and was forced to withdraw. The other achieved total success, stabbing a sentry before bombing dugouts, taking prisoners and retiring according to plan – total Canadian loss was one man accidentally killed and one wounded. Such was the ideal, but it should also be noted that there were many bloody fiascos. A raid by 86 men of the Dorsets, which advanced under cover of a mine explosion, led to four dead and 17 wounded because the enemy withdrew and promptly called down fire on their old position. A 55th Division raid near Blaireville Wood was caught by massive fire before it reached the enemy line, and 60 of its 76 participants were killed or wounded.

Tommies wearing a variety of ‘liberated’ headgear, including a German Guard Hussar busby, Garde du Corps helmet, various Pickelhauben and a French steel helmet. One of the men, centre, has a German Tornister, or backpack. (Author’s collection)

In March 1916 general instructions for raids and patrols were distributed under the title Notes on Minor Enterprises. This document sharpened the focus considerably. Objectives were to be ‘limited and definite’, and the choice of target influenced by any covered approaches to the enemy line, any lack of vigilance identified, and the ability of the enemy to reinforce or cover various parts of his trenches. Preparation of a week or more was recommended for each operation. Experience suggested that patrols of from two to eight were often successful in entering the enemy lines to secure information, whilst ‘raids’ with or without artillery co-operation might be almost any size from 80 to a whole battalion. Artillery was deemed particularly useful for cutting wire before a raid, or forming a barrage around the point of attack. Gas and smoke could be used to divert the enemy’s artillery fire, or to form a barrage to one flank.

From the Zonnebeke sheet, N.E. 1, 1:10,000, with German defences in red, corrected to 30 June 1917. This area was one of the toughest nuts encountered during the 1917 offensive, with the Zonnebeke Ridge which ran from the village in the direction of St Julien infested with machine gun posts. Broodseinde was fought over twice by British 7th Division – once in 1914 and again in October 1917. The German defences are linear in only a few places, being mainly zones of bunkers and shell holes, some of which are disclosed by the presence of the tracks used to reach them. Maps of September 1917 show the main fire trench running south from Zonnebeke as ‘Docile Trench’, with ‘Desmond Trench’ continuing the front uninterrupted north of the road in the direction of ‘Thames’. Further north still the ‘D’ theme of the British names was continued with ‘Dabble Avenue’, ‘Dab’, ‘Dagger’ and ‘Dad’ trenches.

Finds from the trenches at Zonnebeke. Amongst the detritus are parts of rifles and a Lewis gun, German grenades, bayonets, ammunition and personal items. Evocative as such material undoubtedly is, creating a professional museum display of this type poses problems of both safety and long term conservation. (Author’s collection)

German Pickelhauben at the Memorial Museum, Zonnebeke. The distinctive spiked helmet was introduced as early as 1842, and widely copied. The example foreground is of the Prussian Guard infantry; that with a ball finial is an artillery example. The grey pieces have bodies made of pressed felt, a wartime emergency measure. (Author’s collection)

Naturally there are now Canadian monuments in the vicinity, but probably the locations of greatest interest nearby are the Memorial Museum, Passchendaele – which is actually in Zonnebeke and was reopened after substantial renovation in 2004 – and the vast Tyne Cot Cemetery, which actually lies on the old ‘Dabble Avenue’ about a mile north of Broodseinde. Tyne Cot is the largest British and Commonwealth cemetery in Europe, and now also boasts a small visitor centre tastefully tucked away to one side. In the midst of the cemetery the customary ‘Cross of Sacrifice’, which was designed by Reginald Blomfield and appears in most Commonwealth war graves cemeteries, is built over a German blockhouse, an arrangement which it is said was suggested by King George V during a battlefield pilgrimage in 1922.

Not giving away more information than one was able to gather was naturally a key consideration. To this end every precaution was taken against taking documents and insignia on a raid, as an American report, citing British instructions, stated:

Officers in charge of parties will be held personally responsible that all under their command are stripped of all identifying marks. Particular attention will be paid to ensure that the following articles are taken from the men and deposited in sandbags to be left at the regimental transport lines: cap badges, sleeve patches, pay books, regimental buttons, numerals, identity disks, shoulder badges, letters, roll books etc.

Individual schemes were prepared at unit level, but checked at brigade or divisional level. Reconnaissance and observation was an integral part of the planning process. Types of information to be looked at included aerial photographs, patrol and weather reports, prisoner statements, trench log books, and the reports of snipers and artillery observers. Recommended raiding wear now included woollen caps, gloves which might be discarded on reaching the enemy line, and a distinguishing mark that could be seen by friends when crawling but was not obvious to an enemy observer. Though revolvers, clubs, daggers and an issue of two grenades per man were still recommended another trick now advocated was using black insulating tape to attach an electric torch to a rifle. This was ‘found useful for men detailed to clear dugouts’. When Ernest Parker took part in a raid with 2nd Royal Fusiliers he recalled that ‘plain’ service dress was worn, with burnt cork as face camouflage. Though the party included at least one Lewis gun many of the team relied on revolvers, with grenades and torches stuffed into pockets for dugout clearance. These were backed up by knives and clubs, and ‘empty sandbags for souvenirs’. In Parker’s case these would include some ‘scraps of paper’ picked from a dugout, and German shoulder straps from corpses. All was later gratefully received by the battalion intelligence officer, who turned out in pyjamas when the team reported back to HQ behind the line.

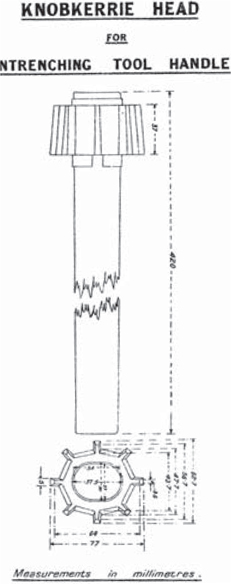

A not untypical raid described by Captain F. C. Hitchcock near Vimy on 5 October 1916 consisted of two assault groups of 14 and 13 men respectively, each led by an officer; a ‘covering party’ of 20 with an officer; and ten men to carry and operate ‘Bangalore Torpedoes’ – these last were a new trench warfare device consisting of a long tube packed with explosive for blowing a path through wire. These efforts in wire cutting were supported both by trench mortars and by scouts with wire cutters, both of which had been operative over the last few days. The attackers carried rifle and bayonet, grenades and ‘knobkerries’ based on entrenching tool handles. These may well have been the type with a metal ‘cog wheel’ head made up especially by the Royal Engineers. Hitchcock explained:

When the enemy opened rifle fire, we judged that the raid was in ‘full swing’. A few of our own wounded crawled back, but they didn’t prove very informative. There was now a good deal of bombing, which showed that they were meeting with opposition. Then some more wounded came back, and were followed by a small party escorting one slightly wounded Hun. Within a half hour from zero all the raiders had returned to our lines. Our casualties were six men wounded. The raiders had a great scrapping in the Hun trenches, and accounted for at least six enemy killed. It was a most successful enterprise… The prisoners, on being given some whisky, became very communicative, and talked of machine gun and trench mortar emplacements, reliefs and casualties.3

Such triumphs were balanced by dismal failures. One such, later described by Rudyard Kipling, was mounted on the Somme on 2 July 1916. It comprised 32 all ranks drawn from 2nd Irish Guards, plus three ‘gas experts’ – who were tasked to locate enemy gas equipment – and an officer of the Royal Engineers. At first, and despite the lightness of the night, all went well with 20 minutes of supporting bombardment. Thereafter everything that could go wrong, did. Alert German gunners returned fire on the British front line, and as the raiders emerged the gunners’ efforts were backed up by machine guns from the enemy second line. Two of the gas team were wounded in No Man’s Land. When the raiders reached the first trench they were checked by bombing and patches of uncut wire. Sergeant Austen was hit and fell into the entanglement. Thereafter many did get into the German line and Lieutenant Pym succeeded in knocking out a machine gun. Bombers now attempted to work their way along the trench, resulting in a ‘general bomb scuffle’, whilst the remaining gas scout discovered nothing. Some documents were picked up, but the man carrying them was killed and the booty lost. As the barrage grew heavier Pym sounded a horn, which was the signal to retire. The Guardsmen scrambled back into the fire with four prisoners – there had been five, but one had been shot when he proved ‘unmanageable’. Two of the remaining four were killed by German shells, as were some of the raiders. Lieutenant Pym was missing near the enemy line, believed killed, and Lieutenant Synge very badly hit in the British front trench. The Engineer officer, theoretically in charge of demolitions, was hit twice before he could achieve anything, but managed to get back. No useful information was gained – it was ‘heroic failure’. The brigadier congratulated the survivors on their ‘gallant behaviour in adverse circumstances’.4

Men of the York and Lancaster Regiment are briefed by a sergeant before starting out for a raid, Roclincourt, January 1918. A variety of crawling suits and camouflage robes are worn – ‘boiler suit’ designs were more popular for raiding as they were less of an impediment when crawling. The men also wear hoods, one of them modified for better hearing. (IWM Q23580)

Though well planned, an enterprise by 2nd East Lancashires in the early hours of 9 September 1916, also on the Somme, similarly achieved very little. This foray, organized mainly to investigate the opposing line and glean identifications, comprised 50 other ranks divided into three sections each led by an officer and provided with mats by means of which they were supposed to cross the enemy wire. It commenced well enough with the attackers crawling up to their start positions just 40 yards from the German parapet. At 2.15am the British artillery laid a ‘box barrage’ around the target zone, and the raiders attempted to storm the trench:

The right party placed their mats but the enemy were on the alert, and the party was unable to force an entry into the trench and after a bombing fight, which lasted for some ten minutes, the party withdrew, firing a green Verey light as it did so. The centre party, under Captain Dowling, entered the trench without opposition, and worked along it to the right and left, bombing dugouts but seeing no Germans. When the green light went up from the right party, Captain Dowling waited for some minutes, and then sounded a Klaxon horn, which was the signal for withdrawing. The left party also entered the trench without opposition, and captured a prisoner. He could not, however, be induced to leave the trench, and had to be left. There was a good deal of fighting with bombs and revolvers, in which Sergeant Brenton distinguished himself considerably: but the party withdrew on the sound of the Klaxon horn without prisoners.5

The raiders lost six men, three wounded and two missing. The gallant Sergeant Brenton was killed by a grenade in No Man’s Land.

By the middle of the war raids could be very large indeed, and were sometimes more like small attacks than pinpricks as part of general reconnaissance. One British raid on the night of 12 February 1917 employed a whole battalion, of whom 162 all ranks became casualties, though 160 enemy casualties were also claimed – plus destruction of 41 dugouts and 52 prisoners taken from a Bavarian Reserve Infantry regiment. Their captors noted that these were of good physique and ‘appeared generally very intelligent’. A more obscure observation was that ‘cotton underclothing’ was worn by all the prisoners: this was probably taken to indicate that the unit had been recently re-supplied, or were new arrivals at the front.

Artwork illustrating British raiders. From left to right:

A) Private, 12th Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment, dressed for a daytime winter patrol in the Arlux area, January 1918. The snow camouflage ‘boiler suit’ was an issue garment introduced in the latter part of the war to be worn over the service dress.

B) Officer, 1/8th (Irish) Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment, 1916.

C) Private, York and Lancaster Regiment, 1918.

(© Adam Hook, Osprey Publishing)

Those on the receiving end of an enemy raid were not supposed to await their fate passively, and orders were often issued accordingly. Some such were disseminated to the company commanders of 1st/5th South Lancashires in early 1917. Captain Dickinson copied them into his Correspondence Book:

Dispositions in Event of Raid

This would be preceded by a heavy bombardment. In this event all men retire to dugouts except two men at each sentry post. A sentry armed with bombs will be posted at the door of each dugout. Immediately fire lifts from the trench everyone will come out [and] take up firing positions. During the bombardment NCOs (including Platoon Sergeants), also Platoon Commanders will be in dugouts either with, or very near, their men. This is important, Sergeants are not to remain in their usual dugouts but to be actually with their men. Grenadier party will be told off for each listening post – an additional grenadier party will be told off now, so as to be ready for use for each platoon. Every man to be acquainted with this – This supercedes the method of edging away to each flank.

Adopting such precautions was not always possible. The 1st South Wales Borderers were caught in the act of conducting a relief in the Maroc sector when struck by a German raid. They were ‘still encumbered with packs and greatcoats and had not yet taken over when a tremendous bombardment began’. The other battalion ‘cleared out’, leaving the SWB to fight off the Germans, some of whom were hit by a machine gun whilst making their escape. Nonetheless the battalion suffered several casualties including a sergeant killed. Lieutenant Davidson had hardly gained his place in the trench before the enemy hauled him away as prisoner.

Raiding techniques were naturally modified to suit the new types of defence as they were brought into use. Eric Hiscock of the Royal Fusiliers described a raid just before dawn against Flanders concrete works, consisting of ten NCOs and other ranks led by an officer:

Lieutenant Clarke, the Company Sergeant Major, and the two Sergeants, carried revolvers. The rest of us carried bandoliers full of cartridges, short Lee Enfield rifles, and small sacks hanging from the shoulder full of Mills bombs… We were to hurl our Mills bombs, then follow up the explosions by dashing round the rear of the pillboxes, entering, and seizing at least one prisoner.

On 1 November 1917 a carefully co-ordinated night raid was mounted by 7th King’s Own Lancaster Regiment in the ‘Bitter Wood’ area: it comprised two officers and 28 other ranks, organized so that groups could attack individual dugouts. Its departure from friendly lines was covered by Lewis guns, and two men with a whistle were left near the jumping off point so that any stragglers could be attracted back to safety. As the battalion War Diary reported:

The raiders crossed the Beek in small parties at ten minute intervals and by 7.50pm had successfully worked their way into a position of assembly about ten yards west of and parallel with ‘Rifle Road’ – about 80 yards from their objectives. At 8.20 our barrage opened on the whole chain of dugouts which were not being attacked. At 8.24 the barrage lifted 150 yards east of the northern group and each party rushed forward to its objective. Dugouts 1, 2, 3, and 5 were found to be unoccupied. Dugout 4 was defended by a machine gun section which in its endeavour to escape was driven by Corporal Woods and his party into the barrage and probably suffered casualties. Lieutenant Holmes went for dugout 6 and found an entrance on the far side guarded by two sentries. These he promptly shot and they fell back blocking the doorway. The occupants of the dugout were firing through the entrance and prevented our men from getting in. A bomb was therefore thrown in. A machine gunner who opened out through the loophole was shot through the loophole by one of the men. Corporal Storey in the meantime was dealing with dugout 7. Lieutenant Holmes went to his assistance and eventually six prisoners were extracted. A further attempt to clear dugout 6 was made by Lieutenant Conheeny but he was held up by fire from within. The object of the raid having now been accomplished, Lieutenant Holmes sounded the signal to withdraw and the whole party were safely back across the Beek with their prisoners by 8.40. Our casualties were nil.

A British officer stands with a bullet-riddled steel loophole plate, July 1916. The modern rifle bullet was remarkably powerful, particularly at close ranges. Though some loop plates were left partly exposed as deliberate decoys, they were most effective when integrated into earth or sandbag defences and carefully camouflaged. Such work was best undertaken at night or otherwise screened from the enemy. (IWM Q120)

Some of the weirdest patrols of the war were undertaken by two battalions of the East Lancashires at the northern end of the Allied line, where their positions butted against a canal in September 1917. Here intermittent shelling and gas were the order of the day:

Conditions in the front line were accordingly unpleasant, and such of the men and officers as were strong swimmers found themselves in the disagreeable situation of being detailed for swimming patrols. These patrols, clad in nothing but their skins and a waterproof bag containing a revolver slung around their waists, were assigned the unenviable task of descending from the British lines to the muddy edge of the canal, swimming the two hundred yards width of the canal to the German side (in itself no mean task, considering the run of the tide) and then of wandering, naked and shivering, on the enemy side to try and ascertain at what distance from the bank lay the occupied German trenches – there being certain trenches shown on field maps quite close to the edge of the water which proved to be unoccupied. No information of value was ever ascertained by these patrols other than the fact that the trenches referred to were unoccupied, but it speaks volumes for the spirit of the troops concerned that on one occasion a non-commissioned officer of the 2/5th Battalion who was a famous swimmer in his home town, once swam, not only across the Yser canal, but out to the end of the jetty or pier protruding into the sea from the enemy side and there affixed a small Union Jack…6

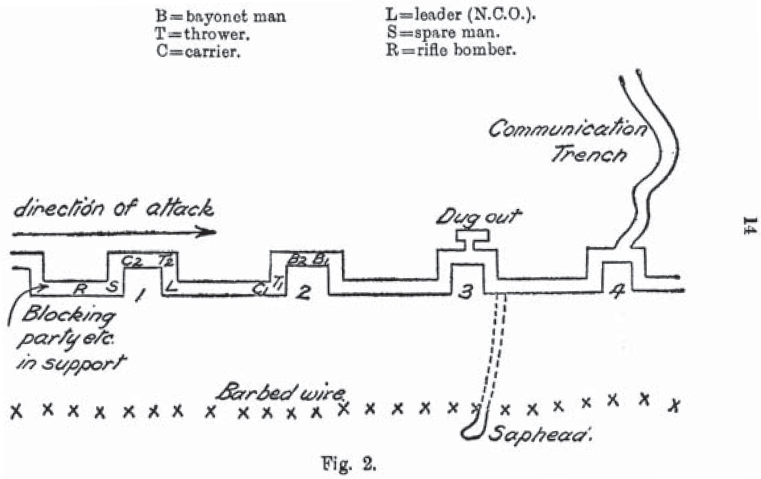

Line drawing from Instructions on Bombing, 1917, showing the tactics of the ‘Bombing Party’. (Author’s collection)

Perhaps the ultimate summary of British raiding methods came in the December 1917 manual Scouting and Patrolling. Now the principal duties of scouts and patrols were recognized as essentially ‘pre’ and ‘post’ attack missions. Before offensive action scouts were to reconnoitre enemy wire, locate machine guns and snipers, and generally provide intelligence. Patrols were to achieve ‘complete mastery’ in No Man’s Land. In a post-offensive situation scouts were to locate the enemy’s new positions, attempt to ascertain his intentions, and act as guides. Patrols were now to follow up the retreating enemy and ‘seize tactical features’.

Diagram from Work of the RE in the European War, showing the Knobkerrie head for entrenching tool. (Author’s collection)

As before much of the work would be done at night and was likely to focus around operations to gain information; kill, capture or harass the enemy; or protect vulnerable areas. Patrols were not to move until they had become accustomed to the dark, and at least one man was to remain listening whilst the remainder were in motion. Basic formations were described for patrols from two to nine men, and 20 was the recommended maximum for a ‘fighting patrol’. In the largest patrols the men formed boxes around a Lewis gun for firepower, whilst a five-man patrol was ideal for two bombers thrown forward with three riflemen behind, through which they could retire. Men on patrol work were to go lightly equipped:

A cap comforter is least visible, the face and hands should be darkened and gloves may be worn. Each man should carry two bombs, a bayonet or knobkerrie, and a revolver or rifle. A revolver is more convenient, but men so armed must be expert in its use. The rifle is the best weapon for purposes of protection… Scouts going out on patrol should have nothing on them which would assist the enemy if they were captured.7

Training for patrol work now included night exercises in which men were taught to differentiate the sounds of digging, marching, wire cutting, talking, whispering – and how far such sounds travelled under differing conditions of wind and weather. They also learnt various tricks to distract attention, and quiet movement, crawling and communication. Groups were instructed how to maintain contact with each other by touch, means of string, signals, white badges and even ‘luminous marks’. Special ‘Crawling Suits’ also made their appearance during 1916 and were in widespread use by the following year.

By now patrol reports were expected to follow a standard form, with the information requested being the most important part and therefore forming the first section. To this was to be appended a map reference sheet; a list of personnel with names, ranks and numbers; time and place of departure and return; and a list of casualties and any details of how these occurred. The whole was to be signed and dated at a given place by the author. The task of patrol report writing, often not welcomed by the exhausted, was made slightly easier in some units by the provision of a standard ‘Patrol Report’ template. That of 42nd Division from early 1918 consisted of boxes for ‘composition’, ‘task’, times and places of exit and return, and a space for a sketch map. The main body comprised a brief chronological narrative. Interestingly it was now assumed that the person leading a small patrol, and hence writing the report, might be a sergeant.

Heart stopping as raiding and patrolling might be there were at least a few who preferred it to other possibilities. P. H. Jackson of 6th Manchesters recalled for example that in his battalion scouts were exempted from fatigues or inhabiting the front line trench unless slated for a patrol. The scouts formed a self-contained group of four, occupying a hut near battalion headquarters, and one man would remain behind to attend to rations whilst the other three were on patrol. Nevertheless by the end of the war there was an expectation that patrolling would be a normal part of the soldier’s experience, not a specialized skill. As Hints on Training explained in May 1918, ‘Patrolling must be done by roster and not on the voluntary system; every man in the company should be used for patrolling.’ Moreover the ideal patrol was not only one with specific objectives, but one so organized that sections participated under their own section commanders. In any case there was a point of view that in the trenches danger and fear were perfectly natural. As Lieutenant Colonel J. S. Y. Rogers, Medical Officer to 4th Black Watch, opined:

I think every man, no matter how brave out at the front, has experienced fear. You cannot avoid it with the various things that are going on. A man in the front line is under constant stress of excitement. He does not know when he is going to be shelled or sniped or undergo the dangers of patrol duty. He may be mined underneath; he does not know when the mine is going up. He has a fear of gas… They are not cowards.8

At first glance one might be forgiven for thinking that there was no connection between the rough but noble engagement of ‘minor enterprises’, as raids were called in official publications, and the ‘dirty’ game of sniping. In fact the two were soon intractably associated, for both were seen as methods to interfere with the enemy, and to gain intelligence.

To begin with sniping was an ad hoc undertaking, with no special training, and haphazard provision of equipment – this being whatever came to the front on the initiative of individual officers who had been target shooters or big game hunters. So it was that the soldier was stalked like game, and shot with high-powered sporting rifles such as the Jeffreys .333, .416 Rigby and the .280 Ross. Indeed the reactions of men aimed at by the sniper’s bullet were much the same as those of large animals. A near miss would often cause a man to pause for a fraction of a second before ducking, or moving sharply away. A hit caused an instant reaction with buckling knees, or instantaneous flinch. Fatal wounds often caused the victim to fall forwards and slip down – rarely did a man throw up his arms or fall backwards. Experienced shots would look out for such signs when wondering what retaliation might be due from the enemy line, and when to relocate.

Orders for scopes were placed with classic gun makers such as Purdy, Holland and Holland, Churchill, Lancaster and Westley Richards. Soon ‘magnifying’ or ‘Galilean’ sights were also employed – these being separate convex and concave lenses mounted atop the rifle. Yet for the first year the Germans had clear advantage. There were two main reasons for this, the first being that in Germany, as a land of forests, game, shooting clubs and military conscription, there were already numbers of men trained in the arts of field shooting. The second, less obvious, was that the optics industries of Europe were centred in Germany, and supplies of telescopic sights and binoculars were more easily obtained in Central Europe. As Major Hesketh Pritchard reported:

At this time the skill of the German sniper had become a byword, and in the early days of trench warfare brave German riflemen used to lie out between the lines, sending their bullets through the head of any officer or man who dared to look over our parapet. These Germans, who were often Forest Guards … did their business with a skill and gallantry which must be freely acknowledged. From the ruined house or the field of decaying roots, sometimes resting their rifles on the bodies of the dead, they sent forth a plague of head wounds into the British lines. Their marks were small, but when they hit they usually killed their man, and the hardest soldier turned sick when he saw the effect of the pointed German bullet, which was apt to keyhole so that the little hole in the forehead where it entered often became a huge tear, the size of a fist, on the other side of the stricken man’s head.9

An illustration of the Symien Sniper Suit from The Principles and Practice of Camouflage, March 1918. (Author’s collection)

Moreover, as Major F. M. Crum of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps observed, the ‘Bosche’ remained ‘top dog’ in 1915. Crum himself was first employed leading snipers in Sanctuary Wood:

We lie in wait for them from dawn to dusk; there are always some of them watching with their eyes glued to the telescope. They become each day more cunning, and have great duels with the enemy’s snipers. Sometimes we disguise ourselves by wearing a sandbag, sometimes with a mask of brown or green gauze, or with grass and bushes, or it might be a common masquerading mask painted like bricks or stone… The German sniper has iron loopholes; you watch and watch, and at last you see the slot slowly opening, the muzzle of the rifle being gradually pushed forward. This is the time for your marksman to shoot, but sometimes he shuts up his porthole quickly, like a snail going back into his shell. Now that’s the time for the elephant gun – a steady aim and bang goes the steel bullet through the steel plate.10

During the latter part of 1915 and 1916, however, British sniping was revolutionized, both by an influx of new equipment and by the establishment of ‘schools’ behind the lines and in the UK. Colonel Lloyd’s X Corps School was set up in 1915, and the same year Major Hesketh Pritchard began an itinerant teaching mission around the Corps of First and Third Armies, bringing with him telescopes and rifles from the UK. In May 1916 a brigade, later army, sniping school was opened at a disused quarry at Acq, which included a dummy German trench occupied by instructors in enemy uniforms. XI Corps School was at Steenbecque under Lieutenant Forsyth of the Black Watch, and was one of the inspirations for the large First Army School near Linghem which instituted a 17-day course. The Fourth Army School was set against the huge natural backstop of a steep chalk slope at Bouchon, and eventually equipped with a prefabricated ‘farm building’ which could be moved about. The Northern Command School at Rugeley Camp in Staffordshire, operating under Lieutenant Colonel Fremantle, printed its own little textbook of notes for its instructors in December 1916.

Artwork showing British Snipers. From left to right:

A) Sniper from the Irish Guards, with a camouflage hood made from a sandbag and local vegetation. He is holding an SMLE with Lattey optical sights.

B) An individual sniper, 2nd Lt, 2nd Bt. DLI, armed with a sporting rifle from 1915.

C) Sniper wearing camouflage: a long, loose canvas robe of light green, splashed with disruptive daubs of black, white and light brown paint. The rifle is camouflaged with hessian strips. It is an SMLE with an off-set telescope, c.1916.

(© Adam Hook, Osprey Publishing)

From practical experience and training emerged a systematic approach. Each battalion was now to have a minimum sniper establishment of eight men (a figure which was later increased, and could be as high as 24 in some units). These were intended to operate as two-man teams, spread across the battalion front, usually with one man observing, preferably with a rested telescope, the other ready to take shots. Though naturally one of the team might be better at one task than the other occasional changes were useful to keep the team alert. Their work was co-ordinated by an officer who kept plans of the posts, took back reports of enemy activity – and made sure that his team were kept fresh by reduced fatigues. For consistency of shooting each man attempted to stick with one rifle and the same batch of cartridges, kept clean and corrosion free. On firing usual practice was to look in the general direction of a target, often found by the observer, then bring the scope up to the eye. Searching using the scope was a useful supplement to the observer, but not the best way to take a fleeting shot – which was often all that was presented by a gap in sandbags, or a wary working party. Sights were not usually adjusted in action, but left set at perhaps 200 yards. The sniper could then act swiftly, correcting his aim as he lined up the target, higher for more distant, lower for closer – slightly ahead of a moving soldier by ‘aiming off’. As Colonel Lloyd observed, trench sniping was ‘the art of hitting a very small object straight off and without the advantage of a sighting shot’.11

Contrary to popular belief most sniping was done at relatively close ranges, and moving targets in particular were not much engaged beyond 300 yards. Indeed one of the key, and most dangerous, sniper tactics was to move closer to the enemy, perhaps slithering out of a sap or tunnel at night, and into a firing position which enfiladed an enemy post, or took an unexpectedly low angle on a loop or fire step. A long wait might be rewarded by a single clear shot before another long wait and retreat to friendly lines. Such work was best done wearing a sniper suit or robe and hood painted to match the local background, or with a speckled ‘domino’ cape which was particularly suited to conditions such as light filtering through trees or foliage. Where crawling forwards was too dangerous or restrictive, some snipers preferred to crawl a few yards back from their own trench line – which lengthened range slightly, but might create a different field of fire.

By the end of the war the two main issue patterns of sniper garb were the ‘Symien’ sniper suit of painted scrim, and the ‘boiler suit’ type, both commonly used with scrim hood, rifle cover or camouflage, and gloves. Expert snipers rarely shot from an obvious loophole, but from tunnelled lairs, prone from amongst heaps of earth or rubbish, or from within some location in deep shadow. Where armoured loops were shot from, best practice was to have a multitude of them. As Hesketh Pritchard noted, the Germans often had numerous loopholes:

Many steel plates were shoved up on the parapet in the most obvious positions. These were rarely shot through, but they were certainly sometimes used. The German argument must have been that if you have thirty loopholes, it is thirty to one against the particular one from which you fire being under observation at that particular moment.12

Snipers of US 168th Infantry at battalion headquarters, Badonvillers, May 1918. The rifles are .30 bolt action, 1903 model, Springfields. The modern-looking, and very effective, camouflaged suits break up the human form with nondescript shape as well as by means of colour and foliage. Hands and faces, often apparent to an observer, are also obscured. (IWM Q65492)

The sniper post was addressed at some length in the Northern Command Notes. The ideal was a place that commanded weak points in the enemy line, overlooked the enemy wherever possible, but was well concealed. Mostly these would be within 100–700 yards of the enemy. Somewhere within the parados at the rear of a friendly trench was one possibility, but the corner of a traverse in the parapet was also handy. Posts that were bullet, rain and sun proof as well as reasonably comfortable were most suitable for long-term observation – with alternative posts for relocation. Ideally the muzzle of the sniper’s rifle would not project out of a post, and where this was likely to occur a pipe or sandbags could be arranged to conceal it. Openings would be made less obvious by being irregular, and by placing different coloured sandbags at intervals; covering with gauze or rubbish would also help. Disguise could include dummy loopholes, perhaps with a dummy rifle, or a black lining and some broken glass inside, to mimic the reflective nature of optics at a distance. Posts were best worked on at night with disposal of any freshly dug earth elsewhere before dawn. Major Crum’s ideal post was somewhat different, being a gently sloped alcove off the forward side of the fire trench, within the parapet, and lined with sandbags and other materials to allow the prone sniper to remain in comfort for some time. It was protected from the front by a loophole plate, but so positioned that the plate was within the earth, rather than outside. Sandbags filled with scrap iron could also be judiciously used for increased, but not obvious, bullet protection.

From the Richebourg sheet, 36 S.W. 3, 1:10,000, with trenches corrected to 22 December 1917. The battle of Neuve Chapelle, fought in March 1915, saw British First Army seize the village at a cost of 13,000 casualties – but German reserves rushed to this sector prevented any possibility of a breakthrough. The village later changed hands again. Two and a half years later the enemy was still barely 500 yards from what little remained of the settlement. Myriad drainage channels show that this area was no rest cure in wet weather.

The British trenches and thoroughfares, marked in blue, show an interesting history through their names. ‘Baluchi Road’ and ‘Gurkha Road’ are reminders of the presence of the Indian Corps in 1914 and the subsequent attack by the Meerut Division. An Indian memorial now stands at the La Bombe crossroads. ‘Oxford Street’, ‘Liverpool Street’ and ‘Edgware Road’ are all London inspired – ‘Hun Street’ was probably once an enemy trench. The British have given the German trenches in the ‘S’ area opposite a predictable theme – with ‘Sandy’, ‘Sampson’ and ‘Solomon’. ‘Molly’ and ‘Mitre’ are associated with the ‘M’ area. At the northern edge of the map can be seen the distinctive symbols of mine craters – which, being in red, are currently in enemy hands. In 1918 the ruins of Neuve Chapelle were held by the Portuguese, whose military cemetery is also nearby.

German troops make emergency repairs to a front line trench. Both the elements and shells could cause maintenance problems for the trench garrison. If walkways were allowed to remain blocked the flow of reserves and supplies could be disastrously impeded, and fire positions go unmanned. Very heavy bombardments or repeated shelling over long periods filled in trenches, blocked entrances, damaged drainage and degraded obstacles. Conversely new tactical features appeared in the form of shell holes. (Author’s collection)

‘After Relief from the Trenches’ – the appearance of one German Frontschwein (literally ‘front line hog’) after a tour of duty. This man has used sand bags and sacking to create both improvised cape and knee pads. Though many Germans sported beards, which cut down on the amount of personal grooming required in the front line, these were later discouraged, or cut back, to allow the proper fitting of full face gas masks. (Author’s collection)

In December 1917 the role of the sniper was succinctly described in Scouting and Patrolling. Snipers were useful in both ‘open’ and ‘trench’ warfare. In the former they could be employed in both attack and defence, from concealed positions and as a counter to enemy snipers and machine guns. Additionally they could be used as a precaution against counter-attack when an enemy trench had been seized. From here they would creep a few yards further forward and occupy a shell hole or other suitable position whilst their comrades consolidated the trench. Picking off the first enemy to appear would deter counter-attack, and give alert to friendly troops. In static trench warfare a good network of snipers’ posts could be arranged so that the whole of the opposing line could be kept ‘under telescopic observation’ and any enemy head showing at up to 300 yards brought under fire. Friendly casualties caused by rifle fire were to be investigated and snipers detailed to deal with the threat. The sniper posts were to be used for firing at ‘live’ targets only, whilst periscope smashing and firing armour-piercing rounds at loopholes were best done from elsewhere. Posts that had been discovered and fired upon by the enemy were to be put out of bounds for at least seven days, and preferably abandoned altogether.

As Scouting and Patrolling suggested:

The sniper should make use of veils, sniper suits, camouflage etc. when available and Scout Officers should keep themselves up to date with the latest ideas. The study of protective colouring is interesting and of value; but it must be impressed on the Sniper that, however well his disguise may conform with his surroundings, if he does not learn at the same time to keep still, or, move only with stealth and cunning, he is likely to disclose his position… Disguises may be improvised by using grass, leaves etc., and by smearing hands and face and kit to harmonise with surroundings. A regular outline of any shape attracts attention.