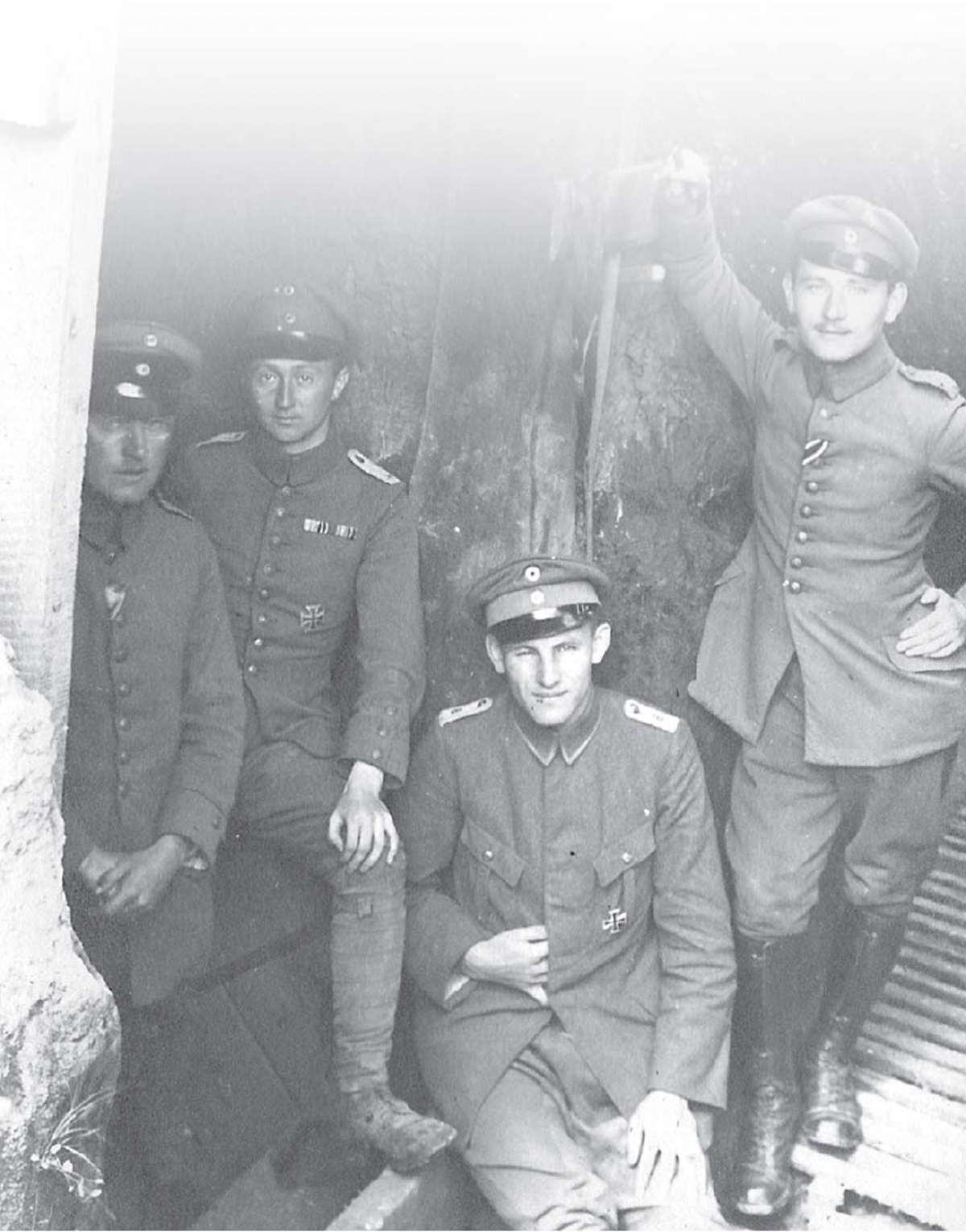

German officers at the entrance to a deep bunker. The steps lead down from the forward lip of a trench for maximum protection. The trench itself is boarded, and a raised wooden lip at the dugout entrance is intended to reduce the amount of water or detritus flowing down. According to the 1916 manual Stellungsbau, deep dugouts were unsuitable for the first line, being difficult to exit quickly. Further back, where cover 5 or more yards deep was advised for shell protection, bunker exits were to be unobstructed, and at least 1.5 yards from trench traverses. Two of the officers here wear the Iron Cross First Class. This was pinned directly to the uniform, unlike the Second Class type, which was suspended from a black and white ribbon on official occasions, and represented only by a piece of ribbon on combat uniform. Founded in 1813, and re-instituted at the outbreak of war, the cross patée shaped medal was awarded approximately 163,000 times in the first class, and 5,000,000 times in the second by November 1918. (Author’s collection)

As we have noted the first year of war saw the development of complex trench systems that became wider, and often physically deeper, with the passage of time. Early single lines with a support were soon supplemented by second, third and even fourth lines – critical points being reinforced with redoubts and strong points. Sandbags, wire and other materials were supplied more efficiently and in greater quantities. Defences were now often miles rather than hundreds of yards in depth. Led by German tactical analysis of the defensive battle, and an increasing emphasis on the role of the machine gun, there was a growing realization of the importance of posts and zones which formed a skeleton within the trench system. Progressively, and with a thinning of the trench garrisons, theorists laid more emphasis on the web of defence points, and less upon the ideas of linear obstacles and cover.

In 1916 Stellungsbau, the new German manual ‘of the construction of field positions’, became the engineering and defensive tactician’s bible. The basic purposes of works remained the same: economy of forces; diminution of loss, and increase of loss to the enemy; and utilization of the ground so as to produce favourable conditions for combat. The way this was to be achieved had, however, changed out of all recognition since 1914. Now the first position was to be ‘close up to the enemy’, and was to consist of:

a trench system of several continuous but not parallel lines, at 150 to 200 yards distance from one another. The lines are to be connected by an ample number of communication trenches. Communication rearwards is ensured by approach trenches, which can never be too numerous. All the above trenches are to be so adapted to the ground, that, as far as possible, the enemy cannot see into them anywhere. A short field of fire is sufficient. Behind the first position at least one rearward position should be prepared. The same general principles hold good for this. It should be at such a distance that a simultaneous artillery attack on both is not possible. The distance will, therefore, vary from 4 to 10 kilometres.

Illustrations from the German Stellungsbau, 1916. Fig 2 shows a communication trench block. Figs 33 and 34 show shell-proof MG emplacement and enfilading wire while Figs 49-51 demonstrate different shelters. (Author’s collection)

Nor was this all, for each of the main positions would consist of at least three lines, and between the lines of each position, and behind the rear position, every spot was to be prepared for defence – with many ‘strong points’, ‘holding points’ and ‘posts’. ‘Strong points’ were defined as defended villages, woods and the like, whilst ‘holding points’ might be smaller features such as shell holes, small trenches, ruins or thickets. The strong points were to be gradually joined up by fire trenches and obstacles to create new lines, and blockhouses built in woods, thus creating ‘a broad fortified zone’. Artillery observation posts were particularly crucial in the forward areas, and the defensive line itself was best placed on rear slopes, even if this entailed reduced fields of fire. In rearmost areas the most cost effective method was to fortify a few posts and dugouts but leave the intervening trenches until later – as extensive trench works required continual maintenance and would needlessly absorb resources.

The particular importance of posts in creating the skeleton was not overlooked:

Machine gun positions and dugouts form the framework of all infantry fighting lines. A hundred metres or less is sufficient frontal field of fire. Machine guns should be concealed in emplacements; they must enfilade the obstacles, the space in front of the obstacles, and the ground between different lines and positions from higher ground, if possible. They must, therefore, be scattered. The few guns used in the front line must endeavour to increase their power by mobility.

The Boyau de Londres – London Trench – Verdun. This trench, parts of which survive, is a fairly late French construction intended as a communication trench to the forward forts. Unusually, parts of it are revetted with original prefabricated concrete panels. (Author’s collection)

Interestingly, dugouts in the rear were to be stronger than those in the first line – presumably because the heavier enemy guns were usually trained on the more distant targets, and it did not matter so much if a rear area dugout took time to exit. The garrison of the forward defence was to be sufficient to deal with any ‘surprise attacks’, but the bulk of the troops were to be held back, being accommodated in the rear lines, ground between the lines, communication trenches and countryside behind the first position. As Hindenburg would later explain:

our defensive positions were no longer to consist of single lines and strong points but of a network of lines and groups of strong points. In the deep zones thus formed we did not intend to dispose our troops on a rigid and continuous front but in a complex system of nuclei, and distributed in depth and breadth. The defender had to keep his forces mobile to avoid the destructive effects of enemy fire during the period of preparation as well as to abandon voluntarily any parts which could no longer be held.1

Considering actual dimensions and details of works, Stellungsbau came to the conclusion that though narrow trenches gave best protection they were inconvenient for traffic and prone to blocking. For this reason narrow works were only of use as a temporary expedient, deep and broad trenches being generally preferable. Revetting was desirable where watery conditions might lead to collapse, but far less important than the construction of new works. Armoured and other loopholes were useful, but probably only required in every second bay of the fire trenches since major attacks would also be met by machine gun fire and general fire over the parapet. Communication trenches were ideally deep, sinuous and provided with recesses every 55 yards which served as cover from shrapnel and as posts for runners. Sortie steps were useful in places for quick entrance and exit. Communication trenches were similarly to be provided with the means to create a block, perhaps with a loopholed traverse and a barbed wire obstacle ready to be pulled into position. ‘Splinter proof’ dugouts were deemed of only marginal use, and fortification builders were urged to devote their efforts to ‘shell proof’ and ‘bomb proof’ shelters, these latter being defined as capable of providing protection from ‘continuous’ shelling from 21cm projectiles, and single hits from heavier guns. Concrete and deep mining could both give such protection, but the former was accounted best, as relatively tough shallow concrete works were easier to exit.

By the middle of the war German wire was usually thick and effective, and absorbed considerable labour. As the Summary of Recent Information explained in January 1917:

Every defensive line, switch and strong point is protected by a strong wire entanglement on iron or wooden posts, sited, if possible so as not to be parallel to the trenches behind it. Endeavours are made to provide two or three belts, each 10 to 15 feet or more deep, with an interval between belts of 15 to 30 feet. These intervals are filled, if possible, with trip wires, pointed iron stakes, etc. and blocked by occasional bands of entanglement connecting the belts. Four different lengths of iron screw pickets are supplied, the longest, which has five loops, giving a height of 4 feet above ground. The distance apart of the pickets in an entanglement is intentionally irregular, but averages about 6.5 feet.

Concrete bunker, Hill 60, Zwarteleen, Belgium. Interestingly, Hill 60 is essentially manmade, being composed of spoil from the nearby railway cutting. As one of the few rises it was eagerly contested. The German works here were undermined, then assaulted by the West Yorkshires in June 1917. This bunker is a curious amalgam, being an Australian observation post (facing east) constructed atop an older German pillbox. It lies within a couple of hundred yards of the enormous ‘Caterpillar’ mine crater. (Author’s collection)

The use of concrete certainly aided the development of stand-alone strong points and bunkers, though it was first thought of merely as a more effective form of reinforcement. Reinforced concrete doorways were less liable to collapse, and layers of concrete, combined with earth and wood, were found to be more effective top cover for dugouts – as a ‘sandwich’ construction could burst the shell, and contain some of the shock by virtue of the different properties of the materials. Short sections of trench might also have concrete works built into them, as for example in ‘under parapet’ shelters. Though concrete was seen in pre-war fort construction its widespread adoption for fieldworks took some time. During 1915 the Germans began to organize transport of basalt and gravel using Rhine barges through the neutral Netherlands, off loading at points on the River Lys, thus supplementing the production of cement works nearer to the front such as those at Antwerp and Mons. An important realization was that concrete, especially with steel reinforcement, could make an effective protection without the need for very deep excavations. In Flanders, where deep digging was made difficult by the water table, concrete works would become crucial, and were in fact widely used by both sides. In German parlance concrete works were often known by the acronym MEBU, or Mannshafts Eisenbeton Unterstände – ‘ferro-concrete personnel dugouts’. The term ‘blockhouse’ was already very familiar from the Boer War, and British troops also used the descriptive term ‘pillbox’.

Though some concrete works had embrasures for machine guns and rifles, quite a few did not. First aid posts and rear area bombardment shelters did not need them, and perforation significantly reduced ballistic resistance. Even in the front line many bunkers were designed essentially as temporary shell protection for a section or two of troops, who would immediately emerge to fire over the top of the work, or disperse into nearby trenches and shell holes. German concrete structures appeared in numbers during 1916. By early 1917 the wide range of standard model works included observation posts incorporating rails for reinforcement; a bell-like iron reinforcement and aperture intended to be used with a mirror or stereoscopic binoculars; a machine gun post with side apertures for enfilading fire; a two-storey ‘battle headquarters’; various command posts, ammunition bunkers, battery positions and shelters for supports. Some of these latter were designed as tubes, gaining additional strength from their shape. A nine-man Gruppe in such a tube obtained about 1 square yard of floor space per person. Perhaps the most frightening fieldwork was the ‘low shelter’, a coffin-like alcove 2 yards long into which a few men could squeeze themselves, but only when prone.

The yardstick conclusion of German engineers was that 30 inches of concrete was sufficient for a general ‘shell proof’ construction, half this being adequate ‘splinter’ protection. German concrete bunkers were constructed using both ‘wet’ concrete and prefabricated blocks. Designated ‘mixing places’ just behind the front line were used to make pouring concrete, with blocks manufactured further away as at the Wervik factory. On larger jobs light railways and tramways were used to move the materials. Standard fortification concrete was cement, sand and stone ballast in a 1:2:4 ratio, though this was reduced to 1:2:2 and the water content increased in reinforced structures to ensure that the mix flowed around the metal rods or joists. In block constructions the concrete bricks could be slotted together with rods on site to create a stronger structure. Though the works that remain today often appear very obvious cubes in the landscape most were originally well concealed. Some were deliberately placed in folds in the ground. Others were made to appear like agricultural buildings, or were built into genuine farms, and many were wholly or partially buried, or obscured with brushwood. The texture of the wet concrete was sometimes broken up with sacking and shapes concealed with netting.

Over 2,000 German concrete works were built around the Ypres Salient alone. As General Gough explained, this was ‘a different system of defence’, powerful and made more so by mud and drainage ditches, impossible to locate precisely from a distance, safest from all but the very heaviest shells, and very much like a series of small forts.2 Though battered and furiously fought over a majority of these bunkers remained usable even in mid 1918. Some had been bodily lifted or had subsided but remained intact. Reports noted:

Most of the dugouts have been hit, and except for some in the front line, where the concrete appears to have been poor or the thickness insufficient, they have not suffered. One farm has been bombarded by ourselves and by the enemy for over a month, and is none the worse… The effect of shell fire on these structures has been practically nil, though the intervening ground is a mass of interlocking shell holes.

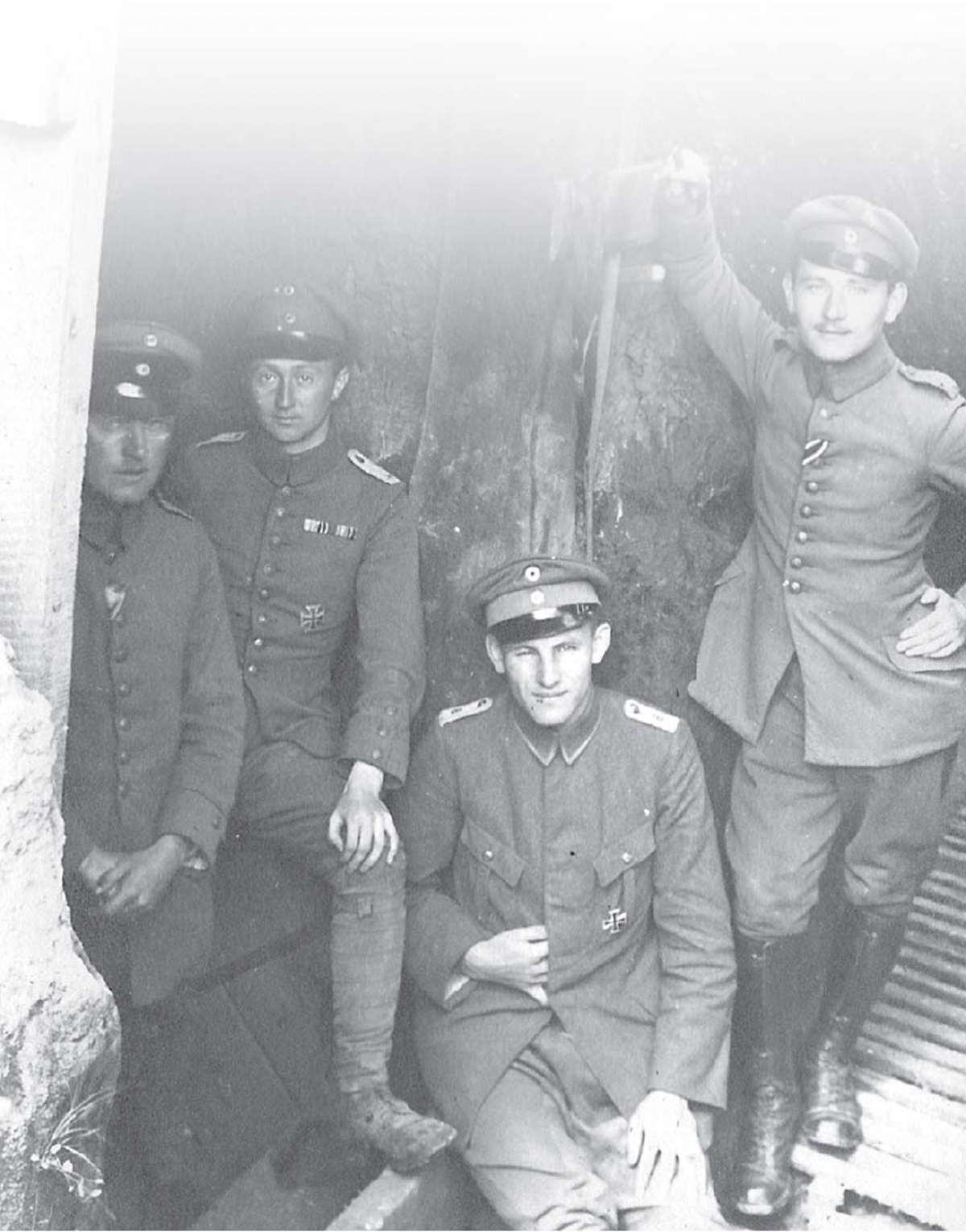

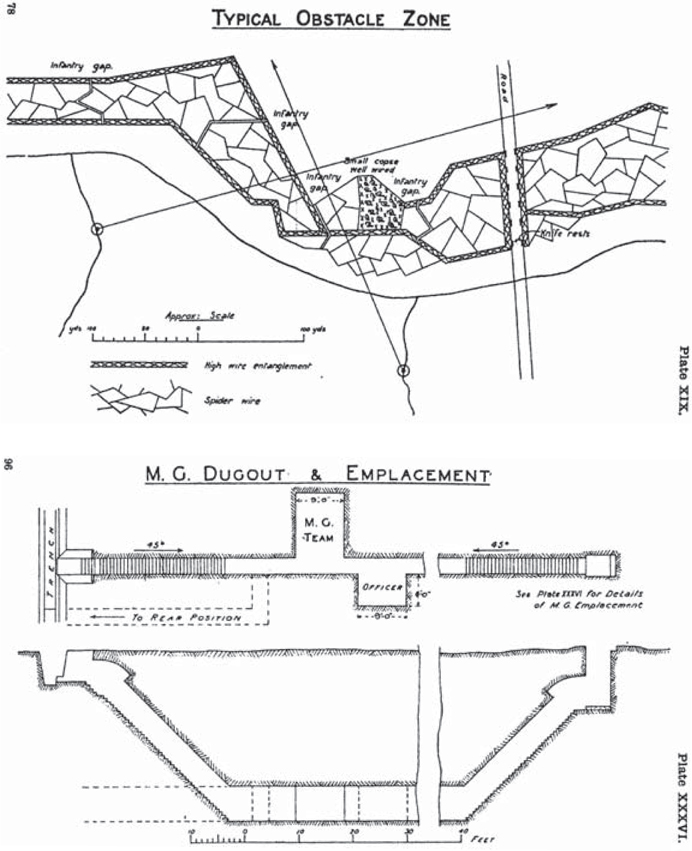

The German obstacle zone, near Arras, June 1917. Strictly speaking this particularly fearsome entanglement is not ‘barbed wire’ but ‘razor wire’, as it is formed of serrated bands cut from a steel sheet – not made by attaching ‘barbs’ to wire. Laid out in front of the trench system, belts of wire provided early warning, hindered attack and funnelled the enemy into the path of machine guns. Often obstacle zones were formed of multiple belts with gaps between: such elaborate obstructions were difficult to clear either by shelling or by teams equipped with cutters and explosives. (IWM Q2548)

From the Ploegsteert sheet, 28 S.W. 4, 1:10,000, trenches corrected to 1 April 1917. In this map we see the eastern edge of the famous Ploegsteert Wood and the German trenches opposite. The village of Ploegsteert, known to Tommy as ‘Plug Street’, lay to the west and south of the wood, and often served as a reserve billet for troops manning the line. The British trenches, in blue, are shown only in outline, the enemy trenches, in red, in considerable detail. In this area the English names for the German trenches all begin with ‘U’ – hence ‘Umpire’, ‘Umbria’, ‘Ultra’ and ‘Ulster’. ‘Uncle’ trench is the German second line. What passes for landmarks have been given names that bear mute witness to the destruction of war – ‘Broken Tree House’, ‘Flattened Farm’ and ‘Dead Horse Corner’ being just the most obvious. Mine craters, two held by the Germans, and three held by the British, are marked within a few yards of each other just to the north of Le Pelerin, close to the ‘White Estaminet’. Remarkably another mine laid in this vicinity in 1917 lay dormant until it finally exploded – in 1955.

The wood was first taken by British cavalry in 1914, but part was later retaken by the enemy who were not actually driven back to the positions seen here until 1917. The next April it fell again during the Spring Offensive – and was only completely cleared by British 29th Division on 4 September 1918. ‘Hunter Avenue’ was one of the main thoroughfares through the wood, photographs of 1917 showing it as a roughly boarded ‘corduroy’ track passing through trees stripped of foliage. Both British and German concrete works from the latter part of the war survive on the fringes of the wood. ‘Laurence Farm’ – seen left of centre in square 27 – was sketched by Winston Churchill when he was here with the 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers.

British and German soldiers on the 11th Brigade front at Ploegsteert fraternizing on Christmas Day during the unofficial, but widespread, truce of 1914. The bearded smoking German, right, wears the spiked Pickelhaube with cover, and the early type regulation greatcoat with coloured collar patches. Several men have soft caps, scarves or pullovers against the winter weather. (IWM Q70075)

Often the combination of concrete and scattered ‘defence in depth’ worked all too well, economizing on troops and creating a very tough nut to crack. At Passchendaele in 1917, for example, the defences were arranged as a series of zones, studded with concrete. The foremost parts, along the Pilckem Ridge and western part of the Gheluvelt Plateau, were merely the ‘outpost’ zone of a ‘battle zone’ that covered the reverse slopes and ran back to the centre of the plateau. Beyond this were a third line and a rear zone. Further back had been created a ‘Flanders I’ line, and two further lines, ‘Flanders II’ and ‘III’, had just been laid out. Making progress through this would be expensive. Just one example from the battle was the advance of 1st Irish Rifles up Pilckem Ridge. The battalion followed a bombardment in an open ‘artillery formation’, but was not impeded so much by linear defence as by machine gun and sniper fire – much of it from a flank less affected by the shelling. The cost was 36 dead and 167 wounded and missing. The adjutant, Lieutenant Whifeld, was the only officer to survive the attack unscathed. As he later remarked, he was ‘surprised to find so few dead’ in the German line, ‘showing that the enemy was evidently distributed in depth and that we should have a tough time’.

Though less enamoured of concrete British engineers were by no means ignorant of its use. In the La Bassée sector, for example, many tons of cement, sand and shingle were used as an antidote to swampy ground. Manuals of 1916, such as Notes on Trench Warfare for Infantry Officers: Revised Diagrams, did include reinforced concrete, most notably as a ‘bursting course’ in shelters designed against 15cm projectiles. There was also reference to a double-skinned concrete machine gun emplacement incorporating a blast-cushioning air space between the layers. Concrete had also been used for some time for ‘hardening’ specific points such as exposed observation posts and dressing stations. Similarly the Royal Engineers experimented with a front line concrete Lewis gun post, which was calculated to take 20 men 14 days to complete. Yet for two apparent reasons concrete was not widely used in the British front line. The first of these was that British forces expected to be on the offensive, and putting resources into fixed defences was not first priority. The second reason was the natural corollary of the first: for if the British attacked they moved forward, and, even if territorial gains were trivial, lines of fixed defences were quickly rendered useless. Interestingly British theory of 1916 suggested that, particularly in the front line, machine gun dugouts could be counterproductive, since any obvious work would attract artillery fire – which it was assumed would lead to their destruction. ‘Bomb Proofs’ were therefore only to be located where the enemy could not see them, and these were essentially cover during bombardments. Actual machine gun firing positions would be carefully concealed nearby, but might not be ‘hardened’ at all. They would be approached wherever possible by covered saps, tunnels or any other means presenting no obvious track way to give away their position.

Württembergers of the 123rd Grenadier Regiment ‘König Karl’ conduct a ‘louse hunt’ through their clothing behind a front line concrete bunker in Flanders. This regiment was part of the highly respected 27th Division, and spent much of 1916 and 1917 in the Somme and Ypres sectors. Though many pillboxes now stand as obvious cubes, proud of the surrounding landscape, most were not constructed in this way, being semi-submerged, linked by trenches, or hidden within other buildings, camouflaged with earth and vegetation, or painted. This well-concealed structure is designed with firing positions to the rear, and a ‘knife rest’ of barbed wire to prevent attackers clambering in. (Author’s collection)

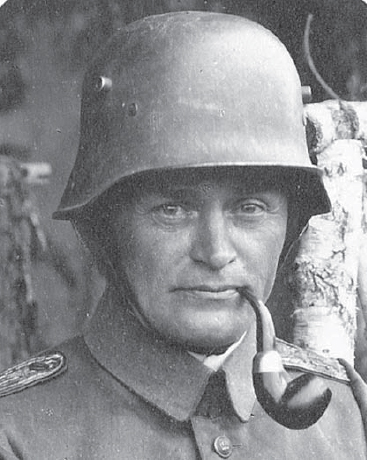

The Stahlhelm worn by a pipe-smoking German officer. Designed by Dr Friedrich Schwerd the German steel helmet was trialled in 1915, and made a general issue during the course of 1916. It was not bulletproof unless fitted with a heavy brow plate which fixed over the distinctive side lugs, but was capable of stopping the small splinters and fragments which were the cause of many head wounds. Initially regarded with some misgiving it was soon a popular, even iconic, piece of equipment. (Author’s collection)

Even so the toughness of the 1917 German concrete defences in Flanders undoubtedly came as a nasty surprise, and one that the Royal Engineers history readily admits caused a re-evaluation of the significance of such works. The result was a renewed interest in concrete, and a factory for blocks was opened at Aire-sur-la-Lys: a ‘School of Concrete’ was founded in early 1918. Though this would be too little too late to meet the German Spring Offensive, quite a few concrete pillboxes were erected towards the end of the war. These included not only conventional-looking boxes, but ‘Moir’ model machine gun posts and the Australian-designed armoured ‘Hobbs’ post with a revolving cupola.

Arguably the last official outline for a British First World War trench system was that presented in the booklet Field Works for Pioneer Battalions, originally produced in 1918, though many of the copies do not appear to have been printed until the following year. This set the context for trench defences rather more explicitly than earlier instructions. Now it was assumed that the ‘general line of defence’ would be dictated by the strategic situation and ‘higher authority’, whilst the siting of actual trenches would be determined by the need to retain ‘tactical features’ which would ‘screen from the enemy’s direct observation the maximum amount of ground’. The unobserved area would serve for the marshalling of reserves and artillery, ideally whilst denying similar cover to the enemy. The essential parts of the system were the ‘Main Battle Zone’ and an ‘Outpost Zone’, with an additional area for the reserve. The outpost zone alone was from 1,500 to 4,000 yards in depth. The distance between the main battle zone’s front trench line and its support was to be a further 150 to 200 yards, and the distance from here to the rear reserve line about 500 yards. The whole system could therefore range from under 2, up to well over 3, miles in depth. In case of necessity a whole new system was to be constructed behind the first.

Detailed layouts were to be ‘very irregular’, with trenches taking advantage not only of natural cover and folds in the ground, but particularly any ‘water obstacles’ that might constitute a defence against tanks. In all instances the enemy view of the position was to be considered when planning. The outpost zone was to be lightly held, inconspicuous, and should not require ‘continuous lines’ or a high level of organization. Nevertheless ‘artificial obstacles’ and ‘shell proof accommodation’ were to be included in every zone. Trench lines were to be marked out first with tracing tapes, flags, pegs and pickets, the work being done by a ‘tracing party’ led by an officer and an NCO, with as many men as were needed to carry the equipment. Basic dimensions of trenches remained much the same as previously, but particular attention was to be paid to drainage, as it was not safe to assume that if pumps were included in an initial scheme it would prove possible to keep them working indefinitely.

Revetments were divided into two main types. The first were those intended to form a ‘skin’ against the face of earth, held in position by uprights. These revetments were likely to include corrugated iron, expanded metal, brushwood and hurdles, supported by pickets or frames. The second type of revetment was those that were built up like a retaining wall or dam, acting under their own weight. These included sandbags, sods and gabions. Where possible trenches would be dug to take standard frames, made at base workshops, which would also accommodate a duckboard with a drainage channel below. By 1918 the Royal Engineers’ ‘battalion dumps’ usually contained two sizes of ‘A’ frame; corrugated iron sheets; duckboards, with spare slats for running repairs; revetting panels; and hurdles a standard 6 feet by 4. Sandbags were still held, but were regarded as mainly for sap heads and other special tasks. When completed lengths of trench were to be put under the eye of a designated ‘warden’, and immediate repairs would be done by the troops in occupation.

Captured German officers under guard outside a recently captured concrete bunker near Langemarck, 12 October 1917. The highland sentry wears a groundsheet as a rain cape. Heavily fought over in late 1914, Langemarck near Ypres was captured by the Germans in April 1915. It was recaptured by British 20th Division in August 1917; recaptured by the enemy in early 1918; then finally fell to Belgian forces on 28 September 1918. The sombre cemetery at Langemarck is now the main site for German burials in the Salient area. It contains over 44,000 bodies, including a mass grave of 25,000. (IWM Q3013)

Interestingly, though pioneer battalions were to be particularly proficient in the construction of fieldworks, infantry were still expected to get themselves under cover by the swiftest means possible. Whilst formulas of men, per hour, per yard, were still employed, by 1918 the new system of ‘intensive digging’ was used in times of emergency. As Hints on Training explained, relays of one spade per three men, or one pick and two spades per nine men for hard ground, was the ideal balance between economy of weight and economy of effort. So supplied, all tools could be kept at work, at maximum efficiency, day and night – with one of the three-man team digging for all he was worth for a couple of minutes only, before handing the spade to the next. The change over being accomplished with ‘lightning rapidity’, the whole unit could be underground in a 6-foot deep trench in an hour.

Germans in a deep bunker from a work by Elk Eber exhibited at the Haus der Deutschen Kunst in Munich. The original caption states that the subjects are sheltering from Trommel, or ‘drum’ fire. Note the use of a French bayonet as a candle holder. Deep cover saved many lives, but was not necessarily proof against super heavy projectiles, gas, collapsed entrances and surprise attacks, during which the enemy might attempt to bowl grenades down steps. Nerve-wracking bombardment might continue for days, and became a well nigh universal aspect of the trench warfare experience. By the latter part of the war it was usual to shelter troops in parties of one or two Gruppen, or up to about 20 individuals, reducing potential losses. (Author’s collection)

Drawings found at Messines. showing a German dugout with concrete block walls. (Author’s collection)

Whilst a full trench system was still regarded as an ideal, in quite a few instances Allied defensive zones – like the German – came to rely on a series of posts rather than a continuous line. In the case of the South Africans at Delville Wood on the Somme, for example, the first stage of hurried consolidation was the digging of mainly two-man rifle pits. Digging was rendered difficult by tree roots. Lewis guns were then brought up around the perimeter, and once in place supplemented by Vickers guns. Only then were the original pits extended to form continuous trenches, and support trenches dug in Buchanan Street, Princes Street and Strand Street. Finally strong points were constructed by the Royal Engineers. Colonel Tanner’s original intention had been to hold the wood with machine guns ‘with small detachments of infantry’, but was overtaken in this design by immediate enemy counter-attacks which necessitated a larger garrison to resist.

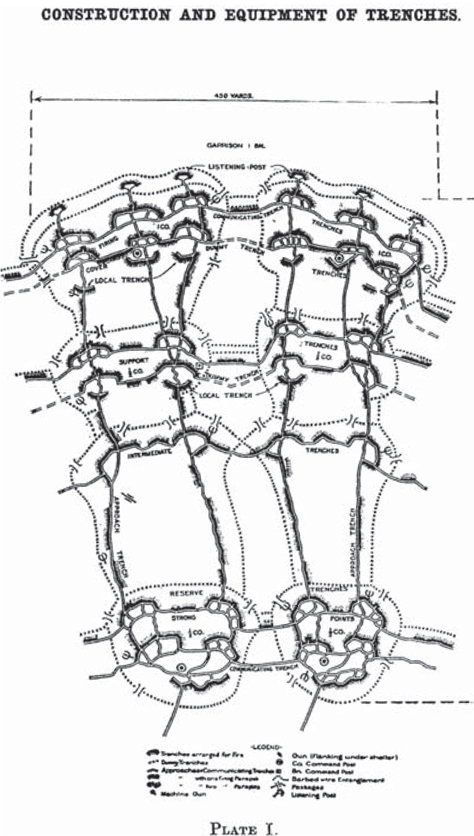

Line drawings from the US Trench Construction and Equipment, 1917. The illustrations show concertina wire and entanglements, a blocking gate for a communication trench and the trench system for a battalion in the front line. (Author’s collection)

As early as November 1916 the forward positions of the 1st/4th Loyal North Lancashire Regiment at Railway Wood were noted as:

a certain number of sentry posts, each consisting of an NCO and, when possible six men – more often four – some posts being Lewis gun posts, others bombing posts, others riflemen only. This line of posts, weak as it is, is strung out between and in front of a series of strong points containing machine guns and an infantry garrison lodged deep in mines, while behind us is the support company ready to come up in case of need, and reserve troops further back; in addition we have the guns, which we can always switch on in a few seconds by telephone or sending up a rocket; all these things give us confidence, weak though we feel ourselves to be.

Sometimes such discontinuity of the line was a conscious tactical choice, but often it was a function of either the terrain or movement that did not give time for a recreation of the ambitious works of the middle war period. British defences on the Lys canal, erected hurriedly in the face of the German offensive of 1918, were described by C. G. Chead of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders as:

small ‘posts’ a few yards distant from each other, each holding about half a dozen men. These ‘posts’ were actually strips of trench with a rather high parapet – open at the rear, made up with very little sand-bagging, protected in front with the usual rows of barbed wire.

Dugouts and shelters for the trench system of 1918 were divided into ‘cut and cover’, ‘concrete’ and ‘tunnelled’ types. Cut and cover models were not to exceed a capacity of 12 men, and not expected to be proof against anything bigger than a 15cm shell. The overhead protection of such a shelter was a five-layer sandwich consisting of a bursting course, cushion, distributing course, second cushion and a thin layer of hard material on the inner face, immediately above the roof to stop splinters. Concrete shelters were to be either of the poured or block concrete types, and to resist a 21cm shell a thickness of 3 feet 6 inches was recommended.

Tunnelled dugouts could be anything up to 40 feet deep, dug according to a number of standard plans, or designed around specific circumstances. The standard plans included HQs, deep shelters attached to MG emplacements, and personnel shelters. All could contain bunked sleeping accommodation. Precise depth and the amount of timber needed in galleries were to be varied according to ground conditions. The biggest tunnelled dugouts were complexes capable of holding complete battalions, and might even be linked to each other, or trench systems, by ‘subways’ – often at about 20 feet under ground level. These subways were wooden lined corridors with a standard height of 6 feet 6 inches and a width of 3 feet 6. These dimensions ensured that all but the very tallest troops could walk fully erect and if necessary pass each other without undue difficulty. The standard subway design of the latter part of the war also allowed for electric lighting with bulbs at intervals protected by expanded metal guards.3

Illustrations from Fieldworks for Pioneer Battalions, 1918. (Author’s collection)

Tunnelled dugouts had the advantages that they were easy to conceal and gave better protection. On the negative side they were difficult to exit. For these reasons they were to have a minimum of two entrances at least 40 feet apart. Nevertheless there were still accidents, such as that which overcame part of the ‘Hedge Street Tunnels’ complex of dugouts, south of the Menin Road, near to a location known as ‘Tower Hamlets’, in January 1918. Fire broke out underground, and 2nd Green Howards were forced to seal up part of the system to localize the conflagration:

… when it was reopened some days later by the 20th Division the bodies of our men were found in the various bunks still wearing their gas helmets. Except where part of a man’s body was lying in the main alley there were no marks of burning on the bodies, but everything in the main alley was charred up.4

The notion of multiple entrances to deep dugouts was sound, but sometimes two were not enough. At Turco Farm, for example, the enemy happened to succeed in landing heavy trench mortar bombs on both entrances of a large dugout simultaneously. Signaller Stanley Bradbury of the Seaforths was one of those entombed:

The result was terrific. The whole of the heavy cement blocks crashed in burying those under and near them and the dugout was reduced to a heap of dirt and debris. The dugout had been full of men all sitting on the steps from the top to the bottom. We were blown amongst a heap of wreckage onto the floor of the dugout but beyond the shock had not suffered any injury although from the cries and groans of those who had been on the steps it seemed that many were terribly injured. A state of panic then existed as with intense darkness and the only entrance whereby fresh air could enter the dugout being completely blocked there appeared to be grave fear that we should suffocate.5

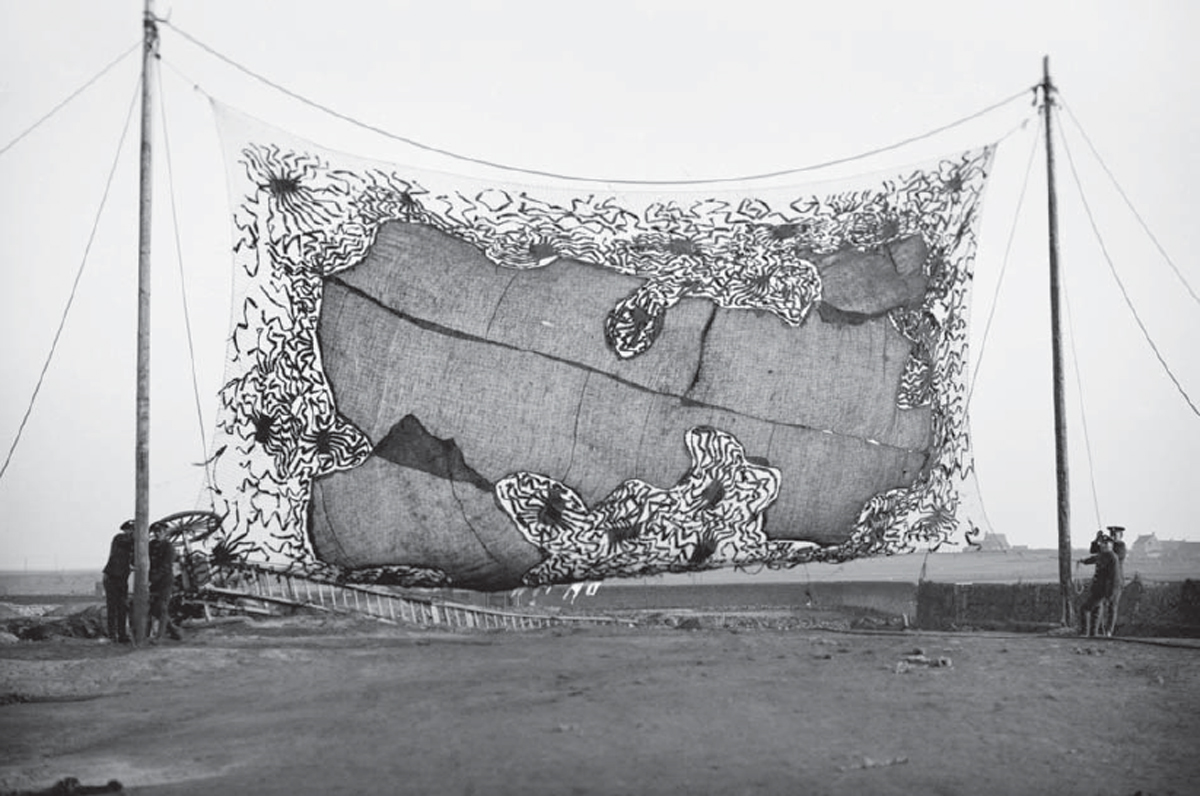

A photograph from the Royal Engineers’ camouflage collection, showing a screen of canvas and ‘fish netting’. The fish net proved effective and popular, and could be garnished with grass, raffia or canvas strips. In many instances it was simply thrown over stores or positions and pegged down. By August 1916 a standard portable kit was devised for the 18-pdr field gun, which included a 30 foot square net with dyed raffia, guy ropes and a light iron frame supported on four ‘gas pipe’ uprights. Almost 13,000 of these kits had been made by the end of the war, and the total output of fish netting was approximately 7.5 million square yards. (IWM Q17791)

A canvas and steel ‘tree’ observation post, near Souchez, 15 May 1918. This idea appears to have been pioneered by the French. The first British dummy tree erected to order by the Royal Engineers was in March 1916 at Burnt Farm north of Ypres, and used real willow bark, sourced from the King’s Park at Windsor, sewn onto canvas. The standard model tree in the Royal Engineers history features bulletproof loopholes for the observer. (IWM Q10310)

Eventually rescuers tunnelled in: of 38 occupants three were dead, and 32 wounded. The problem of ventilation in dugouts was difficult to solve, since lack of ventilation meant possible suffocation, whilst too much ventilation could lead to the ingress of gas, or present opportunities to drop grenades down ventilation pipes – for which reason vents were sometimes kinked or fitted with a trap. Where vents had to be created after the construction of a dugout or shallow mine gallery this was sometimes accomplished using the ‘Wombat Borer’, a giant two-man hand-cranked drill with which the operators bored upward.

Impressive as tunnelled dugouts became, the ultimate in underground accommodation were the caves of Arras. This town near the front line was built of a form of hard chalk, much of which had been mined locally, and the caves were discovered by the military in late 1916. They were found to extend up to 60 feet underground and were conveniently located between the town and front line. Soon it was decided that the caves should be occupied and connected to the front via subways, excavated mainly by the New Zealand Tunnelling Company. These 3 miles of subways contained not only electric lighting, but water mains and supplementary dugouts. There were nine major caves and a complex of mainly smaller ones, these latter being known collectively as the St Sauveur caves. Many had multiple entrances. The total capacity was reckoned at a staggering 11,425 men – or the better part of a division. The bigger caves were identified by suitably New Zealand-inspired names such as Wellington, Christchurch and Auckland, whilst the St Sauveur caves were named after British towns and Channel Islands, hence Crewe, Glasgow, London and Alderney.

Like concrete, camouflage and the associated art of screening also grew in sophistication and organization as the war progressed. The uniforms of many units had acquired dull hues as early as the 19th century, and foliage had been used for centuries, but it is claimed that one of the first real attempts to hide large objects in World War I came in September 1914 when French artist Guirand de Scevola conceived the idea of hiding his gun battery behind screens of painted canvas. An experimental French camouflage detachment was formed at Amiens in February 1915. Eventually this grew into an entire ‘Camouflage Service’ whose works included not only netting, screens, frames and painting but also more exotic devices such as concealed observation posts and dummy bodies of men and animals. A key adjunct was the use of ‘Army Factories’ and ‘Base Factories’ – the latter being mainly staffed by women and tasked with mass production.

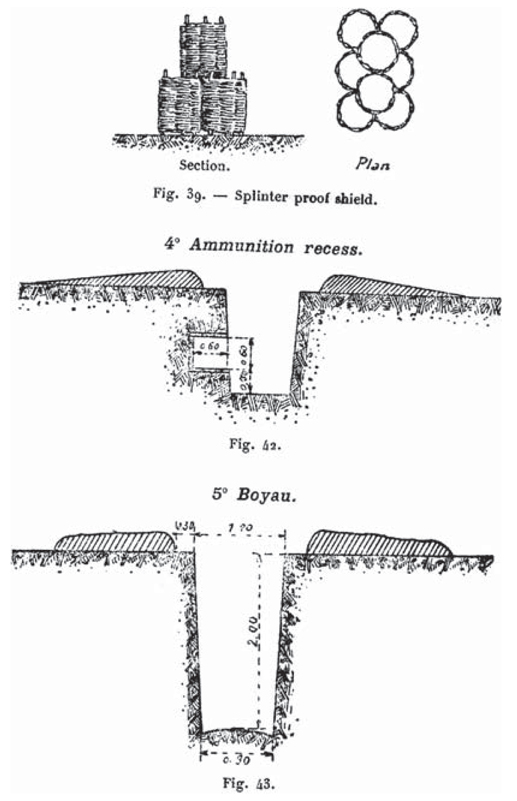

Drawings from the French Platoon Leader’s Manual, 1917, showing trench sections and gabions. (Author’s collection)

In co-operation with the French the British professionalized their own camouflage efforts in the winter of 1915 to 1916, and a full ‘Special Works Park’ of the Royal Engineers was soon in operation. This was expanded to multiple establishments and depots later. Early efforts included disguised observation posts, which might appear to be trees or parts of parapets, and gun covers of painted canvas. Later the product range was extended to the concealment of almost anything, and in their turn American officers were attached to the British camouflage units to learn the trade. By 1918 there were five British camouflage factories under a ‘Controller of Camouflage’. Some of the main British standard items of camouflage included canvas and scrim; wire netting; ‘fish nets’; various types of observation post; concealed periscopes; road screens; sniper suits and ‘Chinese’ figures. These last were wooden cut outs that could be raised suddenly to simulate an attack – though of course these only stood a significant chance of misleading the enemy if used in concert with a bombardment or poor visibility.

The concrete and armoured observation posts atop Fort Vaux, Verdun. This fort, which was effectively the north-eastern bastion of the defence, held on heroically until June 1916, and was recaptured by the French in November. On its outer wall is one of the oddest memorials of the conflict, a tablet recording the pigeon which carried the last message from Vaux by its commander, Commandant Raynal. (Author’s collection)

Though various aspects of concealment were dealt with in different publications such as Notes on Camouflage and Notes on the Camouflage of Battery Positions, the manual The Principles and Practice of Camouflage, of March 1918, was arguably the most important summation. This made it clear that all possible methods of observation and reconnaissance had to be taken into account, including not only eyes and binoculars but also aerial photography, flash spotting and sound ranging. Key concepts in the war against observation included light and shade, point of view, covering evidence of approaches and use, as well as the actual point or object, and shadows and pattern. In addition to standard items ‘special manufacture’ pieces could be ordered through the camouflage officer. It was also recommended that artillery pieces should be camouflage painted: as it was seldom possible to repaint a gun every time it was moved to match the new surroundings the ‘next best thing’ was to attempt to ‘destroy its identity’ so that it was difficult to recognize from a distance. The present scheme of three colour painting with green, cream and brown with a ‘strong black definition between each colour’ was calculated so that one of the three pigments would be likely to merge with the landscape, leaving the remaining areas a meaningless jumble of ‘dissociated pieces’ not readily discernible as a gun.