The male Mark IV tank ‘Hyacinth’, of ‘H’ Battalion, ditched in a German trench a mile west of Ribecourt, Cambrai, 20 November 1917. The infantry are men of 1st Leicesters. The Mark IV featured improvements including better fuel delivery and relocation of the petrol tank, smaller side sponsons and shorter gun barrels, and a better exhaust system. It also lacked the awkward wheeled tail of the Mark I. Entering the fray in mid 1917 the Mark IV had a maximum of 12mm armour and a crew of eight. Its top speed, on ideal ground, was 4mph, a fraction of this over a churned trenchscape. (IWM Q 6432)

Although armour, the gun and the caterpillar ‘track’ all pre-dated World War I the successful fusion of these inventions to create the tank was very much the product of trench warfare. Indeed the tank was introduced as an antidote to the trench, barbed wire and the machine gun. Interestingly, we still think of the modern tank in terms of its three basic original attributes, movement, armour and firepower – the ‘armour triangle’ – the increase of any one element being often at the expense of one, or both, of the others. As early as 1914 Major E. D. Swinton promoted the idea of a ‘machine gun destroyer’, and before long the notion had found influential backing from Winston Churchill, who urged the development of ‘armoured caterpillar tractors’. Various models were eventually put forward to the ‘Landships Committee’ of which ‘Little Willie’ by Foster’s of Lincoln was arguably the first practical design. In answer to War Office specifications further modifications were made, resulting in the now familiar rhomboid contraption which emerged as ‘Mother’ in January 1916. The name ‘tank’ was in fact a cover story intended to make the enemy think that the large riveted metal boxes were ‘water tanks’.

The real problem now was how they should be used. Swinton’s appraisal was that ‘driblets’ would ruin the shock effect, and that ideally tanks should be part of a big combined operation with infantry and gas and that at least 90 machines should be deployed on a 5-mile frontage. Field Marshal Haig would have liked to include just such an attack as part of the opening of the Somme offensive, but producing sufficient machines in the time available proved impossible. Only by mid September were anything like enough completed, and getting them to the battlefront – and beyond this to their starting points – proved difficult. Of 60 tanks, 49 were in working order on 14 September, and of these just 36 were able to join the action at Flers the following morning.

Navigation over a churned morass was so difficult up to the jumping off point that tapes were laid in advance to ensure that at least the tanks started from the right place. Lieutenant B. L. Q. Henriques was one of the tank commanders in the first tank action:

Four [o’clock] arrived and we steamed ahead, squashing dead Germans as we went. We could not steer properly and I kept losing the tape. At five I was about 500 yards behind the First Line. I again stopped as we were rather too early. There was to be a barrage of artillery fire through which there was a space left for me to go. At 5.45am I reached another English trench but was not allowed to stop there for fear of drawing fire upon the infantry so I withdrew 20 yards and waited five minutes… As we approached the German line they let fire at us with might and main. At first no damage was done and we retaliated, killing about 20. Then a smash against my flap at the front caused splinters to come in and the blood to pour down my face. Another minute and my driver got the same. Then our prism glass broke to pieces, then another smash, I think it must have been a bomb, right in my face. The next one wounded my driver so badly we had to stop. By this time I could see nothing at all, my prisms were all broken, and one periscope, while it was impossible to see through the other. On turning round I saw my gunners on the floor. I could not make out why. As the infantry were now approaching and as it was impossible to guide the car, and as I now discovered the sides weren’t bulletproof I decided that to save the car from being captured I had better withdraw. How we got back I shall never understand, we dodged shells from the artillery. I fear that I did not achieve my object…1

A Lewis gun post on the bank of the Lys canal, near Marquois, during the German Spring Offensive, 13 April 1918. The gunner fires through the bank using a wooden box type loop, whilst the sergeant stands ready with a fresh magazine. The team are dismounted tank crew and wear leather equipment; the secondary weapon of the gunner, a holstered revolver, is also visible. (IWM Q6528)

If anything, things were worse in Lieutenant Huffam’s tank:

On moving off we watched [tank] D14, it appeared to stop and immediately exploded. I went to my port side gunners to see why their guns were silent. They never fired again, both gunners were dead I believe, several bullets and small shells had penetrated our armour plate, we were all in bad shape when we were hit by a larger shell, there was an explosion, then fire, and I came round to find myself lying on top of my corporal, his shins were sticking out in the air. I had already been issued with morphia tablets and I quietened him with these and bandaged him with first aid dressings from the others of my crew. We were close to the enemy lines, with my corporal in agony and all others damaged and shell shocked.2

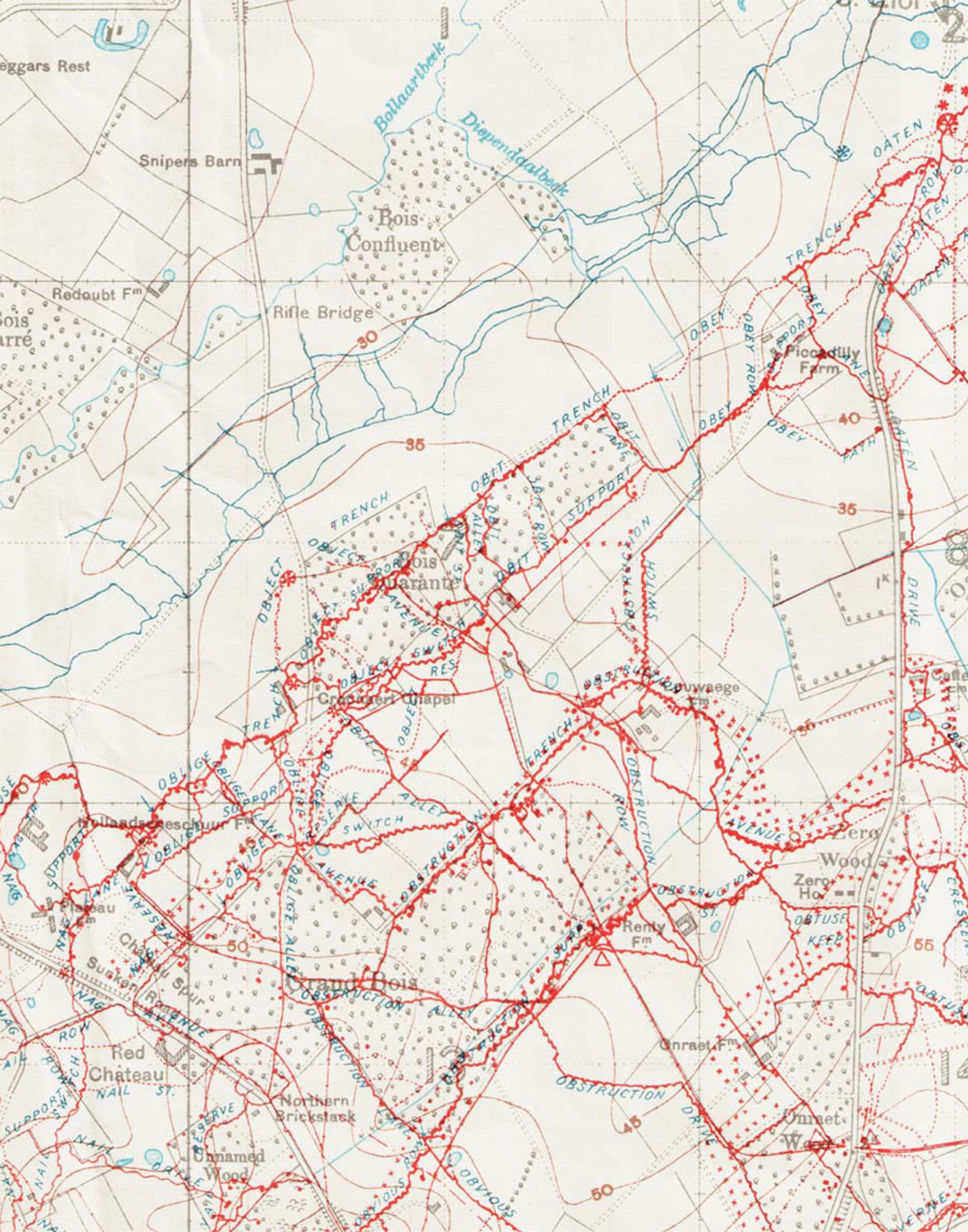

From the Wytschaete map, 28 S.W. 2, 1:10,000, with German trenches in red, British in outline in blue, corrected to 1 April 1917. The Bayernwald – or ‘Bavarian Forest’ – was so called after the garrison who manned this sector of the Ypres Salient near Wytschaete, (known to Tommy as ‘White Sheet’), which lies less than 2 miles away to the south. The local name for this woodland is ‘Croonart’, like the chapel here – or in French ‘Bois Quarante’. Although less well known to English-speaking visitors this area is one of the most interesting on the Western Front, and is one of the places in which Adolf Hitler is known to have served. The defences consisted of a trench system which was eventually studded with concrete bunkers against bombardment.

Archaeological curiosity commenced early, and the site has a long history as a visitor attraction. Schoolteacher Andre Becquart excavated the four prefabricated block construction concrete bunkers here, though other plans show as many as ten bunkers in these woods. The bunkers are relatively shallow and exit direct into the trenches, the largest of them having two doors. In 1971 Becquart investigated ‘Berta 4’, one of the two mine shafts. In 1998 a new round of more systematic work commenced involving the ‘Diggers’ and the ‘Association for Battlefield Archaeology’ under the local council. Interestingly it now proved possible to demonstrate different phases of trench construction, beginning with wood and sandbags, and from 1916 a method of inverted ‘A’ frames at intervals connected by wattle. The Bayernwald reopened to visitors in 2004, though as recently as the summer of 2008 earth movers were again in operation.

Recently re-excavated trenches at the Bayernwald near Wytschaete (now Wijtschate), Belgium. Here is seen one typical German method of revetment, the sides of the winding communication trench being held by a system of posts and willow osiers, topped off by a course of sandbags. Though primitive in appearance this method of trench construction used local materials and benefited from the flexibility of the wood, which could survive relatively near misses and be simply repaired. (Author’s collection)

A German concrete bunker at the Bayernwald. It can be seen that the shelter is built roughly flush with the surrounding ground surface, and entered via the trench. Note the construction, individual blocks of concrete having been cast off site and then used like giant bricks cemented together and reinforced with rods. (Author’s collection)

The first tank attack had been at best a local success – but it was certainly a technical feat and a propaganda victory. Tank D17 ‘Dinnaken’ under Lieutenant Hastie had made it into the village of Flers, putting the enemy to flight, a feat that made newspaper headlines. Field Marshal Haig was pleasantly surprised by their performance compared to a generally lacklustre background, remarking in his diary, ‘Certainly some of the Tanks have done marvels! And have enabled our attack to progress at a surprisingly fast pace.’3 This was enough to ensure orders for a thousand tanks – an extremely far-sighted decision considering the conservative tactical attitudes that had marked the opening of the Somme. Interestingly, improved armour was stressed as an immediate requirement of new production, and so, after day one of the tank’s service life, the battle between the tank and the anti-tank weapon began.

Tanks were used again later in September and in November 1916, and 60 were at Arras in early 1917. At Bullecourt tanks went forward in a blizzard in support of the Australians against the Hindenburg Line. The results of this engagement were far from happy. Just 12 machines were deployed for this part of the operation, of which 11 started out spread out on a front of about 800 yards. Of these four attacked Bullecourt and two the Hindenburg Line nearby. The initial terror the enemy had felt when tanks were first deployed had begun to dissipate, and the dark lumbering monsters were outlined against the snow. According to German 27th Division reports one tank got stuck in thick wire and others became the focus of streams of armour-piercing bullets, direct artillery fire and trench mortar shells. The majority of the tanks were knocked out or damaged and just one passed the first line German trench.

As Major W. H. L. Watson recorded:

The first battle of Bullecourt was a minor disaster. Our attack was a failure, in which three brigades of infantry lost very heavily indeed; and the officers and men lost, seasoned troops that had fought at Gallipoli, could never be replaced. The company of tanks had been, apparently, nothing but a broken reed. For many months after the Australians distrusted tanks, and it was not until the battle of Amiens, sixteen months later, that the Division engaged at Bullecourt were fully converted.4

June 1917 was something of a watershed, for that month the British tank battalions, previously regarded as merely the ‘Heavy Branch’ of the Machine Gun Corps, now became a ‘Tank Corps’ in their own right. Pairs of battalions were brigaded together and old Mark I types were attached as supply tanks. At the same time the new Mark IV took pride of place as the main fighting tank. In many respects the Mark IV was similar to its predecessors, being of the familiar rhomboid design, having a six-cylinder Daimler engine, and a top speed of just under 4 miles per hour. It also came in ‘Male’ and ‘Female’ varieties – the former having two 6-pdr guns and a secondary four machine gun armament, the latter six machine guns only. Nevertheless there were numerous improvements, including relocated fuel tanks with greater capacity which increased the radius of action to 35 miles, and slightly thicker armour. Whilst tanks were still defenceless against direct hits from shells they were reckoned proof against ‘all bullets’. Another innovation that appeared at about this time, and was reported to be the brainchild of Major P. Johnson, was the ‘unditching beam’. This great Baulk of metal-shod oak was supported on rails atop the tank whilst progress was good, but when the machine got stuck in mud it could be chained to the tracks. As the tracks slithered they pulled the beam down in front of the tank and provided traction, allowing the tank to move forward.

Australian engineers of 4th Field Company carry a dummy tank near Catalet, September 1918. Some dummies were for training, but by 1918 the main use was as decoys to mislead enemy air observers. To advise on the camouflage of real tanks a Royal Engineers officer was on permanent attachment to the Tank Corps. (IWM E.AUS 4938)

Despite appalling conditions tanks were deployed at the Third Battle of Ypres. Amazingly they scored some successes even with mud and concrete added to enemy resistance. One such was achieved by Lieutenant Maelor-Jones in tank G9:

At dawn on 31 July I proceeded with other tanks of No 3 Section, crossing over the enemy front line in a north-easterly direction for Kitchener Wood to the right of the Oblong and Juliet Farms. At the latter I waited for our barrage to lift, meanwhile filling up our radiator with water. I then steered for Alberta, leaving it on my left. Here I met some Hampshires retiring. With difficulty I persuaded a man to speak. He told me they were held up by some machine guns. I advanced towards a long blockhouse about six feet high where I observed a machine gun emplacement on which I drove the tank. On the other side I came on a machine gun and two men whom we shot and crumpled up the gun. Advancing we came to an old and strong breastwork manned by the enemy on which our gunners opened fire. The Hampshires then came on and cleared the trench, taking all prisoners.5

It has been said, with some truth, that the battle of Cambrai in November 1917 restored the credibility of tanks – and also convinced the infantry that they were vital to a new era of warfare. All nine battalions of the new ‘Tank Corps’, with 378 machines, took part with a 6-mile line of tanks led into action by Brigadier General Hugh Elles. Following a short and selective barrage the tanks advanced in three waves, dropping fascines into the three lines of trenches to create crossing points. Other vehicles were equipped with grapnels to shift barbed wire, and there were even nine tanks with wireless sets to provide mobile communication posts. Planned essentially as a three-day ‘raid’ the battle was initially a success that it proved impossible to exploit. The commander of ‘H’ Battalion left a graphic account of the working of a Mark IV in action:

Shells were bursting all around us and the fragments of them were striking the sides of the tank. Each of our 6-pounders required a gun layer and a gun loader, and while these four men blazed away, the rest of the perspiring crew kept the tank zig-zagging to upset the enemy’s aim. It was a hard job to turn one of these early tanks. It needed four of the crew to work the levers, and they took their orders by signals. First of all the tank had to stop. A knock on the right side would attract the attention of the right gearsman. The driver would hold out a clenched fist, which was the signal to put the track into neutral. The gearsman would repeat the signal to show it was done. The officer, who controlled two brake levers, would pull the right one, which held the right track. The driver would accelerate and the tank would slew round slowly on the stationary right track while the left track went into motion. As soon as the tank had turned sufficiently the procedure was reversed. Zig-zagging was therefore a slow and complicated business.6

A fighting section was now three machines. In the ‘unicorn’ deployment first used at Cambrai the advance was in a triangular formation with the lead tank pointing toward the objective, and the two rear tanks each leading a platoon of infantry.

By the end of 1917 the tank had proved its worth, and new regularized methods and training were brought forward. A ‘uniformity’ of doctrine was aimed at, based upon commanders training the tank troops they would lead into action. As explained in Instructions for the Training of the Tank Corps in France, aspirations were high:

The object of all training is to create a ‘Corps d’Elite’; that is a body of men who are not only capable of helping to win this war, but are determined to do so. It cannot be emphasized too often that all training, at all times and in all places, must aim at the cultivation of the offensive spirit in all ranks.

Tank battalion commanders were specifically tasked with keeping track of the efficiency of the unit and the ‘mechanical efficiency’ of the machines; detailed reconnaissance of the ground to the front; laying schemes for possible formations, routes of attack and co-operation with other arms; and concealment of the unit. Some elements could be delegated to company commanders, who would also supervise the section commanders in the selection of specific ‘tracks’ along the axis of advance. Battalion and company commanders would be trained specifically on conditions that battle would be likely to produce, the latest details of organization and equipment, and the practicalities of specific ‘schemes’, which were set as outdoor and indoor exercises. The models for these plans would be drawn from real actions of the past year. Individual tank officers were expected to learn orders and timings by heart and to ‘locate all prominent topographical objects in the neighbourhood of the operations’. During the attack it would be their responsibility to see that ‘a sharp lookout is kept for the enemy’s machine guns, signals from our infantry, points where the enemy are holding out, and the progress of the infantry and of the neighbouring tanks’.

A British Mark I ‘male’ tank of ‘C’ Company, broken down across a trench whilst on its way to Thiepval, 25 September 1916. The usual armament of the 28ton Mk I ‘male’ was two 6-pdr guns in the side sponsons and four machine guns; ‘females’ carried six machine guns. Top speed was less than 4 miles per hour, even on good ground, and a gallon of fuel was required for every mile; nevertheless, the Mk I could cross a trench 11 feet wide. The strange superstructure of wood and netting seen here is an anti-grenade precaution: bombs hurled on top of the tank will usually roll off before exploding. (IWM Q2486)

Individual ‘schools’ were used to teach tank skills using training machines on range areas containing trenches. The ‘Gunnery School’ covered the 6-pdr and Hotchkiss guns, which were now the key tank weapons, as well as revolvers, which were the emergency arms of the crews. The teams of the main armament were tried against targets at various distances from moving and stationary vehicles, and machine gunners practised against moving and disappearing targets. Revolver training encompassed not only simple accuracy and care of weapons but realistic ‘trench practices’. In the ‘Mechanical and Driving School’ the trainees were grouped together as crews and taught not only maintenance and driving but night work, ‘unditching’ and camouflage. Instructors took note of the amount of driving each pupil completed, and at the end of the course graded the candidates as first- or second-class drivers, or failures. The failures were further screened so that some were recorded as able to repeat the course, others as ‘unsuitable as a driver’. ‘Wireless’, ‘Gas’ and ‘Compass’ schools dealt with these specialist subjects as they pertained to tank crews.

By 1918 tactics had advanced beyond supporting the infantry into enemy trenches, knocking out machine gun posts and driving up and down the lines shooting up or terrifying enemy troops. Now there were aspirations to break out of and through, not merely into, enemy positions. This was made possible partly by the introduction of new types of machine. The Mark V, which was another conventional rhomboid design, first extended the radius of action to 45, and finally to as much as 67 miles in a version poised to take the field at the end of the war. At Amiens the ‘Carrier’ tanks, armed with just one machine gun, provided a valuable service in taking supplies across the battlefield – according to one calculation effectively replacing the efforts of 2,500 men who would otherwise have been required in old-fashioned ‘carrying parties’. In the summer of 1918 a completely new ‘Whippet’ type also appeared. This was armed with machine guns only, but cut the number of crew required from eight to only four. At the same time it boasted ranges over 65 miles, and a top speed of about 8 miles per hour. It was initially hoped that Whippets could work in conjunction with cavalry and armoured cars, but with or without accompanying horses and other vehicles they managed to cover some impressive distances during their operations and pointed the way to what future armour might achieve.

Though Britain deployed the first tank it is sometimes forgotten how close on its heels came French armour. As early as 1914 a civil engineer called Frot had suggested building an armoured body onto a road roller, an idea that was tested, albeit rather unsuccessfully, the following year. Filtz and Bajac agricultural tractors with wire cutting devices were tried about the same time. Holt tractors with ‘crawler tracks’ were obtained by the Schneider company in May 1915, and one of these was soon armoured as a prototype ‘machine gun carrier’. Eventually a co-operation between Colonel Estienne and Monsieur Brillié of Schneider came up with a design acceptable to the authorities, and a target date of November 1916 was set for the delivery of 400 vehicles.

Despite delays 132 Schneiders mounting short 75mm guns were committed to action on the Chemin des Dames in April 1917. This was a significant achievement, though the first French tank battle was extremely bloody: 76 tanks were immobilized on the battlefield and 57 of these completely destroyed – many of them burned out. As one French tank commander reported:

A few machines were stopped by enemy fire; others, including mine, got into critical positions in shell holes and could only get out again after many attempts. For a few minutes, as I was second in the column, I was terribly afraid of blocking the other 79 tanks which in that spot had no way of getting through either on the left or right. One of my steering mechanisms was broken and all I could do was get out of the hole to clear the way… I cried with rage at our helplessness to repair the tank, and it was difficult for me to follow the stages of the battle; I saw tanks catching fire all over the plain and the first wounded men walking past my vehicle; some tanks were several kilometres ahead of me and pushing on.7

A rival Saint Chamond model was first used in May 1917 when a company of 16 machines, together with Schneiders, supported an infantry attack at Laffaulx Mill. The Saint Chamond mounted a 75mm gun in the bows, but its long body, which overhung the tracks, front and rear, had a tendency to ground. The Renault FT 17, a modern-looking lightweight with a turret, was introduced in early 1918, and large numbers were made before the end of the war. More than 2,000 tanks of French provenance were in service on 11 November 1918, some of the light tanks being with American units. Another 2,000 British machines were in service, giving the Allies total domination in armoured warfare. Little wonder that the Germans focused significant effort on methods to counter tanks in the last two years of war, including the deployment of single guns and whole batteries on anti-tank work, and the invention of the anti-tank rifle. The first ‘AT’ rifle was the Mauser T-Gewehr, introduced in 1918: this was effectively a huge single-shot rifle, firing a 13mm round.

Perhaps oddly, the Germans made least progress with producing actual tanks, partly due to an early underestimation of their eventual worth, and partly due to lack of industrial resources, over which artillery and machine guns claimed priority. The only German-made tank of the war was the monstrous A7V, whose key specifications were not laid down until October 1916. The first battle-worthy vehicle was produced a year later, and only in 1918 were A7Vs committed to action. As finally fielded it weighed 33 tons and was equipped with one 57mm gun and six machine guns and a crew of 18. The total German tank arm in July 1918 was just eight detachments of five tanks each, and of these only three were composed of German-made tanks, the remainder being captured machines.

The eastern part of the ridge from the St Julien sheet 28 N.W. 2, 1:10,000, German trenches in red, corrected to 30 June 1917. The low-lying Pilckem Ridge north-east of Ypres was one of the enemy-held features that hemmed in the town, and stood directly in the way of the 1917 plan to break out towards the coast. The maze of fortification seen here is the German first line, and parts of the second – a third lay further back between Langemarck and Poelcappelle. On the British side these defence lines were dubbed ‘Blue’, ‘Black’ and ‘Green’. The battle of Pilckem Ridge was launched at 3.50am on 31 July with all batteries from 12inch down to field guns firing in the darkness against pre-registered positions. Taking the ‘Blue’ and ‘Black’ lines would cost 30,000 casualties.

British topographers have excelled themselves in finding suitably Teutonic names for the features in this sector, from the ‘Iron Cross’ near the top of square 3, to ‘Mauser Cottage’, ‘Essen Farm’ and ‘Krupp Farm’ in square 14. Many buildings have been given the names of German generals, hence mentions of Hindenburg, Below, von Kluck, Francois and the like. A more satirical mind appears to have dreamed up the names ‘Civilisation’ and ‘Kultur’ for the farms in square 16. Being in area ‘C’ the trenches follow the letter – with such gems as ‘Cake Lane’, ‘Cannon Trench’ and ‘Camphor Support’. What is less apparent and proved even more deadly to the attackers were the many concrete bunkers, some forming shelters within the trench systems, others flanking fire positions.

A packhorse, with a gas mask bag secured to his head harness, is loaded with supplies near Pilckem, 31 July 1917. The long items on top of the burden are metal screw pickets to hold barbed wire in place. Screwing in metal pickets was usually quieter than banging in wooden stakes. (IWM Q5717)

Men of the Irish Guards tend a wounded German prisoner during the battle of Pilckem Ridge, 31 July 1917. The trench is revetted with wooden stakes and wattle. At least two of the men wear ‘Small Box’ respirator bags slung on their chests, another, back to camera, has a ‘Cruise Visor’ hanging from his helmet which is worn back to front. The Cruise Visor was devised by Captain Cruise of the Royal Army Medical Corps, oculist to the King, and was a curtain of chain links for eye protection. It was said to produce dizziness when worn in front of the eyes, and was not popular. (IWM Q2628)

Given the lack of German tanks and the gaps between their battlefield deployments it was not until April 1918 that the first tank versus tank action took place at Villers-Bretonneux. A dozen German machines left the start line in three groups, under cover of fog, and following a fight with machine gun nests managed to assist their accompanying infantry into the British front line, capturing quite a number of troops. The ‘Steinhart Group’ of four tanks, however, quickly found itself confronted by British tanks – and what happened next depends on whose records are used. According to German sources one A7V accidentally overturned and its crew continued to fight dismounted, their tank being later blown up to prevent it being captured. The second German tank was set upon by eight British tanks, and forced one of these to retire, before receiving multiple hits, and itself retiring before being abandoned. The third, supporting the infantry, survived unscathed; and the fourth was in action with another group of seven British tanks. In the firefight between these no fewer than three of the British tanks were claimed put out of action by Leutnant Bittner, and the German machine eventually retired with a damaged main armament. A British counter-attack later retook the ground gained.

The British account of Villers-Bretonneux by Frank Mitchell, commander of number one tank, of 1st Section, A Company, 1st Tank Battalion, awarded the Military Cross for this action, was rather different:

Suddenly a hurricane of hail pattered against our steel wall, filling our interior with myriads of sparks and flying splinters. Something rattled against the steel helmet of the driver sitting next to me, and my face was stung with minute fragments of steel. The crew flung themselves flat on the floor. The driver ducked his head and drove straight on. Above the roar of the engine sounded the staccato rat-tat-tat-tat of machine guns, and another furious jet of bullets sprayed our steel side, the splinters clanging against the engine cover. The Jerry had treated us to a broadside of armour piercing bullets!

Taking advantage of a dip in the ground, we got beyond range, and then turning, we manoeuvred to get the left gunner on the moving target. Owing to our gas casualties the gunner was working single handed, and his right eye was swollen with gas, he aimed with the left. Moreover as the ground was heavily scarred with shell holes, we kept going up and down like a ship in a heavy sea, which made accurate shooting difficult. His first shot fell some fifteen yards in front, the next went beyond, and then I saw the shells bursting all around the tank. He fired shot after shot every time it came into view.

Nearing the village of Cachy, I noticed to my astonishment that the two females were slowly limping away to the rear. Almost immediately on their arrival they had both been hit by shells which tore great holes in their sides, leaving them defenceless against machine gun bullets, and as their Lewis guns were defenceless against the heavy armour plate of the enemy they could do nothing but withdraw… We turned again and proceeded at a slower pace. The left gunner registering carefully, began to hit the ground right in front of the Jerry tank. I took a risk and stopped the tank for a moment. The pause was justified; a well aimed shot hit the enemy’s conning tower, bringing him to a standstill. Another roar and another white puff at the front of the tank denoted a second hit!8

New Zealand artillery personnel in a captured German emplacement near Grévillers, 25 August 1918. The officers, foreground, are holding a German ‘T-Gewehr’ anti-tank rifle: other equipment, including packs and mess tins, can be seen scattered on the ground. (IWM Q11264)

Whippet tanks then came up and joined the fray getting amongst the German infantry. Three of seven returned, ‘their tracks dripping with blood’. Whilst it is clear that the A7Vs had been grossly outnumbered at Villers-Bretonneux it has to be acknowledged that many of the British machines deployed on that day were armed only with machine guns and not really capable of engaging tanks. Moreover, whether the German machines were mainly disabled by enemy shells or their own inherent design flaws mattered little. They were outnumbered, or outclassed, or possibly both. In the armour balance Germany was at a huge disadvantage from which she could not recover.

A cartoon from the Blighty Christmas Number, 1917, illustrating German trench armour. (Author’s collection)