British stretcher bearers carry a casualty over the top of a trench in the ruins of Thiepval, September 1916. German grenades are scattered amongst the debris. Picture by Lieutenant E. Brooks. (IWM Q1332)

Despite what generations of school children have been taught the trench was not the soldier’s nemesis but his friend. Sometimes it was also his grave; but more often than not it was where he hid successfully from shells and bullets, where he lived, worked and sometimes fought. It was not going into trenches that so often signed a man’s death warrant, but leaving them, especially when headed in the direction of the enemy. Paradoxically, therefore, the ultimate terror of the trenches was getting out of them.

Actually full-blown attacks were a relatively rare experience: as Grenadier Guards officer and future Prime Minister Harold MacMillan put it, ‘the thrill of battle comes now once or twice a twelvemonth’.1 But when it did come it was often terrible and spectacular. As the diary of the German 153rd Infantry Regiment recorded of Loos in 1915:

Dense masses of the enemy, line after line, appeared over the ridge, some of their officers mounted on horseback and advancing as if carrying out a field day drill in peacetime. Our artillery and machine guns riddled their ranks as they came on. As they crossed the northern front of the Bois Hugo, the machine guns there caught them in the flank and whole battalions were annihilated. The English made five consecutive efforts to press on past the wood and reach the second line position. Ten columns of extended line could clearly be distinguished, each one estimated at more than a thousand men, and offering such a target as had never been seen before, or even thought possible. Never had the machine gunners such straightforward work to do or done it so effectively. They traversed to and fro along the enemy’s ranks unceasingly. The men stood on the fire steps, some even on the parapets, and fired triumphantly into the mass of men advancing across open grassland. As the entire field of fire was covered with the enemy’s infantry the effect was devastating and they could be seen falling literally in hundreds.

Interestingly, quite a few who went ‘over the top’ regarded it not only as necessary, but also the vital duty to perform. The young Lieutenant Basil Liddell Hart, serving with the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, and later one of the generals worst critics, referred to his possible demise in action as a noble death ‘for his country and the cause of civilisation’.2

German Alfred Väth was perhaps an extreme example of this sort of attitude, but was by no means unique when he wrote in October 1915:

The attack was terribly beautiful! The most beautiful and at the same time the most terrible thing I have ever experienced. Our artillery shot magnificently, and after two hours the position was sufficiently prepared for the German infantry. The storm came, as only German infantry can storm! It was magnificent the way our men, especially the youngest, advanced, magnificent! Officers belonging to other regiments, who were looking on, have since admitted they have never seen anything like it! In the face of appalling machine gun fire they went on with a confidence which nobody can ever attempt to equal. And so the hill, which had been stormed in vain three times, was taken in an hour… But now comes the worst part – to hold the hill! Bad, very bad days are in front of us. One can scarcely hope to get through safe and sound. The French guns are shooting appallingly, and every night there are counter-attacks and bombing raids. Where I am we are only about 20 yards apart.3

A fine study of a German assault squad or Gruppe, autumn 1916. Grenade bags are worn around each shoulder, and a shelter half across the chest. Most of the team carry a P08 Luger semi-automatic pistol, grenades and a trench knife or a bayonet, two each of which are stuck into the ground, centre foreground. Textbook tactics also called for at least a couple of the group to carry a carbine or rifle to engage more distant targets. About 1.7 million Luger ‘Parabellum’ pistols were made by the end of the war. The pistol’s quickness to load and fire, combined with its well-calculated 9mm round, eight cartridge magazine and ergonomic handling, made for a useful trench weapon – though its effectiveness was sometimes compromised by susceptibility to dirt. (Author’s collection)

The problem of the attack was not merely that trenches provided cover, reduced the casualties of the defenders, and tended to bolster the morale of their garrison; it was also one of co-ordination and communication that technology and tactics, as currently pertained, were ill placed to overcome. It is well known that there were many offensives that were more or less bloody failures, but one example will serve to demonstrate that the issue was rather more than a simple equation of trenches acting as a ‘force multiplier’. The battle of Aubers Ridge, fought on 9 May 1915, was famously described as ‘a serious disappointment’, and whilst the 10,000 casualties suffered by British and Indian forces were modest compared to some of the engagements that followed, the battle was a significant one. This would be not least in terms of the way it highlighted problems such as ammunition shortages and communication failure, and the subsequent controversies that helped undermine Asquith’s government.

German machine gun team in a log and earth bunker, c.1916. The MG 08 retains its heavy ‘sledge’ mount, but rests on a semi-circular table arrangement for traversing. It is further protected by a Mantelpanzer, an optional ‘armoured jacket’, with small crew shield. The spherical grenades that lie on the table and hang from the roof in metal holders are model 1915 Kugelhandgranaten. This cast iron fragmentation bomb was particularly useful from cover in defensive situations. (Author’s collection)

On the face of it the plan for a three-division attack was a simple one, formulated at least in part to demonstrate to the French that the British forces were pulling their weight. Field Marshal French deputed the detail of the attack on the ‘ridge’, in fact a gentle rise of about 27 yards, to General Haig, then commanding First Army. Fourteen of the available battalions would go forward, attempting to break the enemy line, by surprise and in two places, supported by a preliminary bombardment of just 40 minutes’ duration. The reserves would mount fresh assaults as required. The attack would cut the road to Lille, forcing an enemy retirement with the ultimate hope of commencing a ‘general advance’. Though publicly optimistic Haig was concerned that there were simply not enough human and material resources: his instincts would be proved correct.

The 2nd Welsh were in the forefront of the southern prong of the attack. As Lieutenant B. U. S. Crips recalled:

We were told that after the bombardment there would not be many people left in the German first and second lines. We were all quite confident and very cheery… My platoon was not to leave the trench for two minutes after the first two platoons had gone. At 5.37am the first two platoons jumped over the parapet ready to charge but they were met with a perfect hail of bullets and many men just fell back into the trench riddled with bullets. A few survivors managed to get back into one of the ditches. My company commander then turned to me before my two minutes were up and said I had better try. So I took my platoon and the other platoon in the company also came and we jumped up over the parapet to charge but we met with the same fate and I with a few men managed to get into the ditch. I was the only officer left in my company, two being killed outright and my company commander and another subaltern serverely wounded. So I had to take command of the company.4

On the northern part of the battlefield the position was no better, and arguably worse. The 2nd East Lancashires, for example, faced parts of 6th and 9th companies of the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment; but despite outnumbering their enemy, solidly constructed trenches, and virtually everything else, was against them. One of the worst aspects was the distance that would have to be covered – anything from 150 to 300 yards of open ground – before the enemy position was reached. ‘Sally ports’ were cut into the British breastworks, but permission to dig further forwards prior to the attack was refused on the grounds that this would ruin the element of surprise. Nevertheless, like the Welsh, the Lancashire men were in high spirits. This hopeful attitude was bolstered by the bombardment, which appeared to be effective. This proved entirely deceptive, for as soon as the first troops left their trenches they were greeted with heavy fire. Indeed many men who had started off from the second-line British trench did not even reach the front line. One platoon was depleted to just one sergeant and a private by the time it reached what was supposed to be the jumping off point.

Later there was even worse to come. In hope of renewing the attack the artillery opened fire again, but the British shells were shared out between the East Lancashires. As one officer recalled:

Suddenly there broke over us a hail of shrapnel. It seemed to come from everywhere except the enemy, and men were being hit right and left. I realised that our artillery was bombarding the enemy trenches, after which we would assault if there were any of us left. From all around came the cries of wounded men mingled with the splitting crash of shrapnel, and every few minutes one’s ears were numbed by bursts of Jack Johnsons behind the forward trench.5

German shock troops practise the attack, working from shell hole to shell hole through the remnants of an obstacle zone, 1918. The advance is in no way linear, but by small groups taking advantage of cover and gaps as they present themselves. Smoke and fog were used wherever possible to avoid the fury of defensive fire: by the last months of the war all major armies were using similar ideas on the Western Front. (IWM Q47997)

So enervated was the battalion that it had to be withdrawn, partly down a sap to the main breastwork, then in dribs and drabs under cover of darkness. Ten officers had been killed, and 63 other ranks. The wounded and the missing totalled 376.

This disastrous day was described in the regimental history as the second worst that the unit suffered in the entire war. It was terrible indeed, and made all the more galling by the ingredient of ‘friendly fire’. However, it is worth noting that, as was so often the case, the wounded outnumbered the dead by a factor of two or three to one. So often we hear stories that battalions were ‘wiped out’, or that they ‘lost’ three quarters of their men – but in fact ‘casualties’ were not ‘fatalities’, and slaughter to the last man was vanishingly rare, if not completely unheard of. Often it was the presence of many wounded that made it impossible for the remainder to act – and the realization that this was so gave rise to the now inhuman-sounding orders that so often forbade attacking troops stopping to aid their fallen comrades. What made the war so awful was not so much the presence of the trench, or loss from one attack, but its duration, scale and all-encompassing nature, making the efforts of the individual appear so futile. Cumulatively, therefore, there were some units in which the numbers of the dead did exceed the original strength by the end of the war.

Moreover, to those who were there it could feel as if battalions had been obliterated in a single day. Prisoners would not be seen for years, and even the slightly wounded might be absent for days, and, perhaps unexpectedly, many of the more seriously injured who did make good recoveries were not sent back to their original units, but to wherever they were needed. Under their new cap badge they were much like any other replacement. To their former comrades they were lost in spirit if not in fact. It is also the case that in most major wars the defeated flee the field of death: the victors pursue them as fast as they are able. The battlefield dead are thus quickly out of sight, if not out of mind. In trench warfare both sides must sit and watch the lifeless bodies of friend and foe for days or weeks afterwards, and, like actors in bad feature films with a dearth of extras, the dead of the Western Front got to play multiple roles. For apart from the grief and shock visited upon their immediate comrades, they might be buried, unearthed and reburied more than once. Confined battlefields added to this sense of the charnel house, since the fatalities of every attack and battle that had occurred there were still there, or lay buried not far away, ready to re-enter from the wings.

At Aubers Ridge the attacks went on throughout the afternoon. Amongst the last to go forward were the 2/3 Gurkha Rifles, as Captain W. G. Bagot-Chester recalled:

We had to advance about 2,000 yards across open country to start with, but we were not fired on until we reached a long communication trench leading up to the front trench line. Of course we advanced in artillery formation [to avoid being caught close together by shells]. Toward the last hundred yards or so German ‘Woolly Bears’ began to burst overhead, and ‘Jack Johnsons’ close by, but I had only one man hit at this point. We then got into a long communication trench leading up from Lansdowne Post to the Gridiron Trenches. Here we were blocked for a long time, shelling increasing every moment, wounded trying to get by us. After a time we got into the Gridiron where it was absolute hell. Hun shells, large and small, bursting everywhere, blowing the parapet here and there, and knocking tree branches off. Here there was fearful confusion. No one knew the way to anywhere. There was such a maze of trenches, and such a crowd of people, many wounded, all wanting to go in different directions, one regiment trying to go back, ours trying to go forward, wounded and stretcher bearers going back, etc. I presently went on to a trench called Pioneer Trench. There I had 26 casualties from shell. Havildar Manbir had his leg blown off, and was in such agony that he asked to be shot. As one got further to the front trench, the place got more of a shambles, wounded and dead everywhere. Those who could creep or walk were trying to get back; others simply lying and waiting. The ground in front was littered with Seaforth bodies and 41st Dogras.6

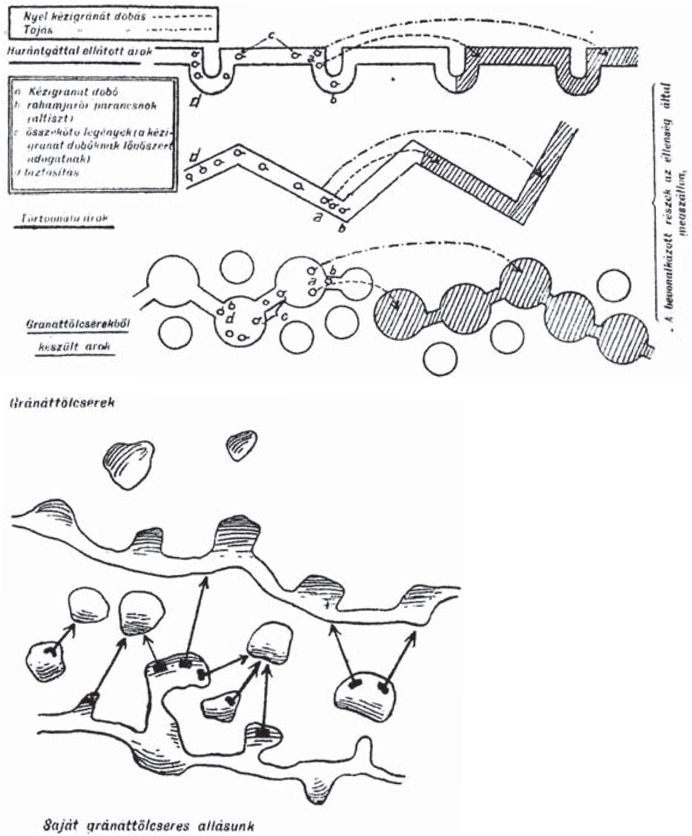

Illustrations showing the German methods of bombing and advancing using trenches and shell holes, 1917. (Author’s collection)

Haig wanted to throw in a final bayonet assault as dusk came on at about 8pm, but it was not to be. The congestion that had defeated the earlier wave now prevented new units from gaining their jumping off points. The battle came to an end. Post-war analysis concluded that there had been several causes of failure. The opening bombardment had been the worst of all worlds: enough to thoroughly alert the enemy, but insufficient to prevent him manning his machine guns and trench parapets. Much of the wire was uncut, and could not be cut later by artillery due to British troops in the vicinity. Friendly machine guns played little part in the action, and such reserves as had got through were not directed to where some success had been gained, but into the teeth of failure. Due to primitive communications the commander did not know with any clarity what had happened or why, and simply sent in more men. Counter-battery fire was totally inadequate due to lack of both guns and munitions:

Our artillery was not able to silence the enemy’s machine guns, much of our ammunition was defective, and the guns also suffered by excessive use, and so our troops as they started their attack came under very heavy fire, which was continued as they tried to cross the few hundred yards of open ground in front of the enemy trenches. That a few of our men did actually enter the German front line was marvellous, but it could lead to no definite result, and they could not be supported.

Two months after the attack Captain Owen Buckmaster of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry peered out from the British line at Aubers and could still see British troops from the battle, packs squared, bayonets fixed, ‘mummified’ on the ground facing an invisible enemy. Rags fluttered in the enemy wire where fragments of uniform had caught upon barbs.

Such is the tragic picture of the infantry attack during World War I. Yet to accept this model as unchanging, and unconsidered, throughout 1914–18 would be entirely wrong. For gradually, if often painfully, the new weapons and techniques were integrated into attacking methods, until an entirely different form of assault had emerged. That this was not immediately reflected in lighter casualties appears to be due to several factors: defenders also learned new techniques and acquired new weapons; communications with attacking formations may have improved but remained problematic; and, last but not least, any attack that involved leaving the relative safety of fieldworks or rear areas was almost bound to involve serious casualties against a determined enemy. Moreover, some of the ‘lessons learned’ during the first year of war were questionable, and though they might have led to more successful local attacks in the short term, also resulted in even higher casualties.7

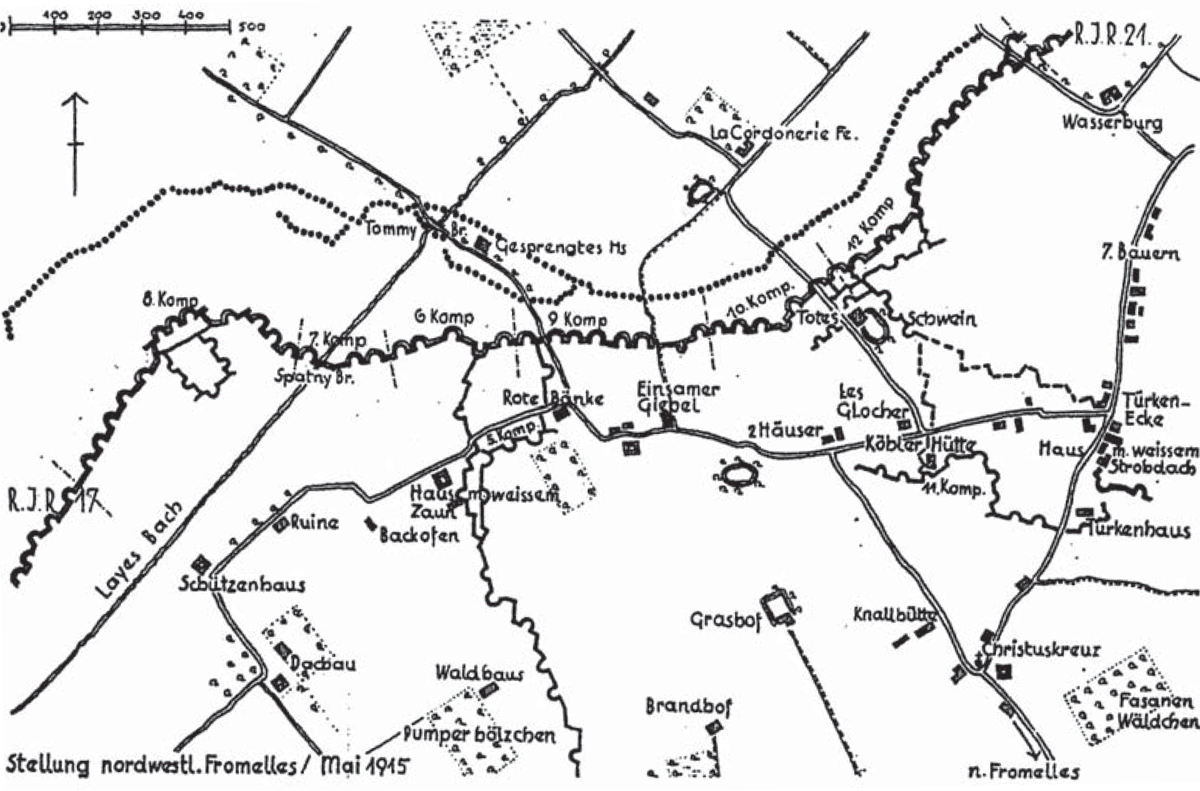

Taken from a German sketch plan of May 1915 we see the area attacked by Major General F. J. Davies’ 8th Division. The British front at the north (top) of the map is shown only as a dotted line, whilst the German front line trench is represented as a schematic series of bays, which are not to scale. The troops occupying the central part of the trench system were of the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment, the various companies being denoted by their number and the abbreviation Komp. On either flank the unit was bounded by the positions of the 17th and 21st Reserve Infantry regiments. The opening British attack came from the area directly west of La Cordonnerie Farm and was made by 13th Londons (Kensingtons); 1st Royal Irish Rifles; 2nd Rifle Brigade; and 2nd East Lancashires. The 2nd Northamptonshires attacked further west still, in the vicinity of the point marked ‘Tommy Br’, which is presumably the bridge across the Layes Bach, or Rivière des Laies. Note also the words ‘Gesprengtes Ms’ marked just inside the British position showing blown mines.

The attack on the morning of 9 May at first managed to cross the narrowest part of No Man’s Land fairly successfully, entering the 9th Company position: two mines blew craters which the Londons were quick to exploit with a ‘magnificent charge’. However, where wider ground was swept by fire, casualties were heavy. As attacks faltered fresh troops from the 2nd Lincolns and 1st Sherwood Foresters were fed in from the rear, Corporal J. Upton of the latter unit being the first of four men to win the Victoria Cross this day. Though the 13th Londons reached the German second line, and two other lodgements were formed by other units, casualties mounted as isolated groups were caught in enfilade fire and confused shelling from both sides. New assaults by other units served only to choke the trenches with dead and wounded. In the mid afternoon and through into the night German counter-attacks gradually forced the British out of the ground they had captured.

In early 1915, for example, French infantry Captain Andre Laffargue reflected on his experiences at Neuville St Vaast, and in a pamphlet entitled L’Etude sur L’Attaque, or ‘A Study of the Attack’, produced a series of ideas that he believed might lead to better results. His first conclusion was that attacks should not be merely ‘progressive’ but ‘forward bounds’ achieving their objectives in a single day. They should be ‘unlimited’ and aim for breakthrough of the trench lines. Artillery preparation would be as heavy and prolonged as required to destroy barbed wire entanglements; neutralize or destroy the defenders of the trenches; prevent hostile artillery from coming into action; block the passage of enemy reserves; and destroy machine guns as soon as they were located. The infantry attack needed to be big enough, and sustained long enough, to capture the enemy’s lines of defence, and by means of reserves pushing through, prevent the enemy from forming other defence lines further back. The advance was to be in lines, preferably with men marching in step to show ‘cool resolution’, but firing on the move if required. The first attacking wave was to carry on with ‘no limit’ unless physically prevented; the second wave would set off as soon as the first reached the enemy trench, and be quickly followed by a third. Since it took time for news of progress to filter back attacks were to be pushed on ‘in a preconceived and almost unintelligent manner till the moment when the last mesh is broken’.

At the end of 1915 and early in 1916 General Foch offered the opinion that it was artillery which was the prime ‘destructive force’ and that it should be applied repeatedly, ‘increasing all the time’.8 Artillery preparation indeed became the ‘measure of the success’ that the infantry could obtain. General Pétain went further still when he stated that artillery conquered the position; infantry occupied it. After the battle of Loos in September and October 1915 British analysts came to the conclusion that lack of any significant success was due to a number of avoidable factors. Important amongst these was the insufficiency of the bombardment, as Field Marshal French had observed:

They’ve dug themselves in their entrenchments so deeply and so well that our shrapnel can’t get at them, and owing to the bungling and lack of foresight at our fine War Office we have only a very insufficient quantity of high explosive… It’s simple murder to send infantry against these powerfully fortified entrenchments until they’ve been heavily hammered.9

Major efforts were put into artillery and shell production so that the scandals of early 1915, when batteries of guns often fell silent through lack of ammunition, should not be repeated. Also deemed of crucial significance was the failure to marshal sufficient reserves at the decisive point – something that French was himself held to task over, and for which he was ultimately sacked. To be successful it was therefore held not only that larger numbers of troops needed to be available close to the centre of the action, but that they should strive to maintain ‘momentum’ – not giving the enemy any chance to react or seize the initiative.

Senegalese troops, 20 June 1916. France deployed Tunisian, Algerian and Moroccan troops from North Africa, and Senegalese and others drawn from French West Africa. The Senegalese formed part of the ‘Colonial Army’ and in 1914 included both volunteers and conscripts. Often village headmen were responsible for providing a quota of troops, initially set at about one, but not more than two, per thousand of the population. Rail transport was quicker than marching, and therefore tended to bestow advantages to defending forces with internal lines of communication. (IWM Q78086)

The lessons of 1915 therefore seemed to be that attacks should be delivered in a deliberate manner; should be commenced with massive artillery preparation; should be as large as resources allowed; and, crucially, should be pre-arranged so that wave after wave struck the enemy, maintaining ‘momentum’ without let up. Once started such an attack would not hesitate to take stock of early intelligence that might well be out of date or wrong, but continue until the whole of the enemy battle position had been swallowed. The gaping hole in the front could then be exploited by a handy reserve which would be able to continue quickly to more distant targets or roll up parts of the front from behind. In the British case such notions were codified in various documents, including The Training of Divisions in Offensive Action of May 1916. Doubtless it was also the case that Field Marshal Haig sought to demonstrate that he was not about to commit the very error of slowness and hesitancy regarding the commitment of reinforcements over which he had helped to have his predecessor, Field Marshal French, removed. These factors set the scene for the ‘Big Push’, and specifically for the opening of the battle of the Somme.

As the American manual Notes on the Methods of Attack and Defense made clear, the British conception of tactics in mid 1916 was by no means unique:

The general method of attack used almost exclusively at present in Europe is to smother the defense with a torrent of explosive shells, kept up incessantly for from one to three or more days, so shattering the defense that they will be able to offer but slight resistance to the advance of the infantry; then to rush forward with the infantry and seize the enemy’s positions while his forces are still demoralized and consolidate them before reinforcements can be brought up through the artillery barrage for counter-attack.

Understandably it is the attacks that lead to heavy casualties which stay longest in the mind – both of those who took part and of those who remember the dead. Nevertheless there were assaults in which few fell, or serious casualties only occurred after an attack had succeeded. At Bernafay Wood on the Somme, for example, the 6th King’s Own Scottish Borderers and 12th Royal Scots crossed 500 yards of flat ground and retook the wood at a cost of six casualties. Occupying the wood for six days led to 316 casualties.

British forces had no monopoly on disaster: at various times slaughter fell upon every combatant. At the height of Verdun German infantryman Georg Bucher reviewed the scene across the front line:

The few hundred yards in front of Douamont was an amazing sight. The dead, mainly Germans, lay in heaps. Then we came to a strip of ground where the French dead lay in rows and groups, the remains of a mass attack which had been repulsed; as they had moved forward, row after row in waves of attack, they must have been mown down by cunningly sited machine gun nests. But where? I could see no sign of such strong points, and I was no longer sure of my direction in the bewildering labyrinth of trenches. Ahead of us more mud-fountains were being thrown up into the air by the heavy shelling.10

Ultimately it would be universally recognized that moving as swiftly as possible from one piece of cover to the next was the best way to advance over the moonscapes that many of the battlefields became. The idea of moving portions of units, covered by the fire of the remainder, had in fact existed well before 1914. Shell hole to shell hole movement was used sporadically fairly early in the war, was tried and tested during raids, and did indeed become the norm during the course of the battle for Verdun. Yet getting this generally accepted, and training troops to perform this apparently simple manoeuvre reliably, was no easy, or overnight, task. Crucially, sections and Gruppe spread around the empty battlefield in penny packets were extremely difficult to control, and thinly spread there was concern that they would not have sufficient firepower to overcome resistance. There was also worry that untried troops would be more likely to falter without the visible support of their comrades and the overseeing eye of officers. Such issues were very much to mind in mid 1916, when British instructions often stipulated that formations be adhered to, and pace of movement regulated to that of the slowest. The horrific results of the plodding advance of 1 July were due at least in part to such insistence on uniformity. As Field Marshal Haig’s notes on a conference with army commanders on 15 June recorded:

The length of each bound forward by the infantry depends on the area which has been prepared by the artillery. The infantry must for their part, capture and hold the ground which the artillery has prepared with as little delay as possible… The advance of isolated detachments (except for reconnoitring purposes) should be avoided. They lead to loss of the boldest and best without result: enemy can concentrate on these detachments. Advance should be uniform. Discipline and the power of subordinate commanders should be exercised to prevent troops getting out of hand.11

Another problem was just what should be carried into the attack. Poor communications and the difficulty of getting supplies across the battlefield suggested that the troops should take with them enough food, water and ammunition to last for a couple of days, plus whatever specialist equipment was required to ‘turn’ trenches, break wire and signal. Conversely the more that was carried the slower and more difficult progress became. French soldier Robert Laloum of the 321st Infantry set out for the recapture of Fort Douamont heavily laden:

Our equipment is amazing. In addition to the regular infantry equipment and our crammed cartridge pouch, we have two gas masks, a haversack for the biscuits, one for beef and chocolate, a third for grenades, two bottles, one filled with wine and the other with water, a blanket rolled in the tent sheet, a tool, two bags. We were all as large as a casket.12

German Funkstation, or wireless post. Radios were still heavy pieces of equipment, and whilst they were eventually introduced to the trenches were not easy to move. By 1918 the German establishment included 26 sets per division, though the majority of these were short range only (capable of ranges from 600 to 6,600 yards) – just one set per division was capable of long-range communication. (Author’s collection)

Led by mounted officers and a machine gun team German troops advance through the Somme village of Etricourt, during the 1918 Spring Offensive. Remarkably some of the buildings seen in this picture are still standing almost a century later. All the ground taken in four months of fighting during the summer and autumn of 1916 – and much more – would be in German hands after just two weeks. Ludendorff’s successful thrust pushed his armies beyond the established trenchscape, but at a cost, and now the already limited supply chain had to pass through the areas of devastation. (Author’s collection)

Instructions on equipment given to 1st Irish Rifles on 1 July 1916 were not untypical of the period:

Rifle, equipment including water-proof sheet (less pack and greatcoat). Haversacks to be carried on the back. Water bottles to be full… Two bandoliers in addition to equipment ammunition (total 220 rounds per man). Bombers and Pioneers will carry equipment ammunition only and Machine Gunners 50 rounds only. Bombers may discard their pouches and carry two bandoliers instead. Iron rations and unexpended portion of day’s ration. Not less than two sandbags. Not less than two grenades. Smoke helmets. Every third man a pick or shovel of which 50 per cent will be picks. The following to be carried by selected men. 130 wire cutters with lanyard per battalion. 64 bill hooks per battalion. 100 pairs hedging gloves. 48 bridges for assaulting battalions. 415 flares per battalion for signalling to Aeroplanes. Each bomb squad, of which there will be one to every platoon, will carry not less than 90 grenades.

Albert Andrews of 19th Manchesters also received some additional embellishments to uniform prior to the Somme battle:

We already had one colour on the back of our tunics, a green and yellow star, which was the battalion colour. We now had to stick a yellow cloth over the flap of our pack – I believe this was for the Artillery Observing Officer to see in the attack how far we had got. On top of this went a tin disc… We had already been wearing short trousers all the summer. These had to be just above the knee and the puttees just below, showing our bare knees, which was all right in the daytime but not at night. Anyway I had a piece of red ribbon which I had to sew round the bottom of the right trouser leg with a bow on the outside. This was to show I was entitled to go down German dugouts after clearing out.13

Over his basic uniform went:

Rifle and bayonet with wire cutters attached; a shovel fastened on my back; pack containing two days’ rations, oil sheet, cardigan jacket and mess tin; haversack containing one day’s iron rations and two Mills bombs; 150 rounds of ammunition; two extra bandoliers containing 50 rounds each, one over each shoulder; a bag of bombs.14

How quickly attacking troops could have moved is open to some debate. Early 19th-century experiments suggested that charging at a full run from much more than 100 yards of the enemy, particularly over rough ground or any obstruction, was likely to be prematurely tiring – and the time to move fastest was when closest to danger. In short there was little point in moving very quickly at any distance from an objective if this meant arriving exhausted, and at a snail’s pace, to be easily shot down at point blank range by a comparatively fresh, or concealed, enemy. On the other hand some units did run and move more freely, and appeared to have benefited from doing so. Attacking rapidly in short ‘bounds’ may still have resulted in heavy casualties on many occasions – but there can be little doubting that bursts of swift movement by troops who threw themselves flat in any cover and regained their breath before repeating the process produced less of a target than those who simply walked forwards. On 1 July 1916, 36th Ulster Division are recorded as rushing directly into action without forming up. The relative success of the Ulster attack was no doubt in part due to great courage and élan, but was also aided significantly by the fact that it started from trenches at the edge of a battered wood quite close to the enemy. The assault could therefore naturally be launched more rapidly than by those who started from completely open positions further away.

Bringing up Mills bombs near Bernafay Wood during the battle of Bazentin Ridge, Somme, mid July 1916. In addition to the grenades, the men carry rifles, bandoliers and cotton drill bags for gas helmets. The bombs were packed with a dozen, and a tin of detonators, in each rope-handled wooden box. Eight such boxes, or 96 grenades, formed a factory ‘lot’. (IWM Q4052)

The Somme was Haig’s worst hour, and the British Army’s bloodiest. The battle had started as a matter of necessity, due to insistence from above and from the French, that something, indeed anything, that could be done should be done, to relieve the pressure on Verdun. At the same time the French had scaled down their own participation in the offensive. To this extent Haig was a victim of circumstance. Yet the idea that bombardment could simply sweep the enemy away had been tried before – and failed before. Using the New Armies in a largely unimaginative manner, ostensibly because it was believed that they could not handle anything more complicated, was also patronizing at best. It was also an indictment of holding them back for over a year whilst apparently ‘training’. By 14 August Haig certainly seems to have realized that the tactics of early July had been a dire mistake – though naturally that of somebody else. According to his own narrative we find him on that day impressing upon General Jacob that the divisions were not ‘to employ so many men in the front line’ and to use Lewis guns and ‘detachments’ instead. He also berated him for the slowness of information in reaching HQ – though how Jacob, or anybody else for that matter, could speed this up was unclear. All this was in direct contradiction of his own instructions of a few weeks earlier. Despite the apparent dawning of clarity Haig still spoke in terms of ‘maintaining steady pressure’, criticized 49th Division for its lack of casualties and failure to salute his car, and greeted his new cavalry general Kavanagh on 9 September with the uplifting news that ‘the enemy seemed to have exhausted his reserves’.

Interestingly, German comments of the Somme period confirm some of the stereotypes that have become part of folklore – whilst rejecting other equally cherished notions. In several instances lack of ‘tactical sense’ was observed, yet increasing skill with small groups and Lewis guns was also seen as a worrying development. The strict discipline in the Kitchener battalions was also remarked upon, which the Germans compared unfavourably with the Territorials. Bavarian reports later noted enemy other ranks as surprisingly physically fit two years into the war, but ‘Australian officers are inferior in every respect to the British’. Another report remarked on 3rd and 4th Australian divisions as ‘poor’.

A problem that dogged virtually every offensive of the war was lack of adequate communications – and this remained an issue even when an attack succeeded. Field telephone exchanges did excellent work, provided the army stayed still and was not heavily shelled. Radios had existed for some years, but they were large, delicate and impossible for infantry on the move to use, though they were put in some tanks and aircraft. ‘Trench sets’ were introduced during 1916. Advancing troops therefore quickly outran their communications, and were reduced to the ancient methods of dispatching runners and visual signalling. In the heat of battle such means often went sadly awry: messages sent at different times overtook one another, others arrived very slowly, some not at all.

A German 21cm Mörser at the moment of discharge. The shells are delivered in wicker containers, seen to the right of the picture, then carried to the gun for loading using the stretcher device, foreground. The crew have stuffed their ears against potentially deafening noise. (Author’s collection)

The usual method to keep communication with the advance was the battalion observation post in the front line equipped with one field telephone, signal flags and runners. Battalions then reported to brigades the progress of the advance by means of telephone or runner. As can be imagined the success of this system rested upon the ability of the observers to see the troops in front of them, or the attacking waves to send back runners. Enemy bombardment might not only hit the attacking infantry but also disable runners and sever telephone wires. Brigades would receive patchy reports, often in the wrong chronological order. Carrier pigeons, signal flares and aircraft could supplement the basic system, but at risk of causing additional confusion. In the event that the attack appeared to be going well battalions would attempt to set up ‘forward report centres’ – the officer and men responsible for setting this up would follow the last wave of the attack.

The idea of attacking ‘waves’ remained current for much of the war – yet the emphasis shifted from relatively rigid formations of riflemen, to looser arrangements in which different echelons performed different functions, as, for example, attacking; mopping up; holding and consolidating. This principle had been established by the end of 1915, and by mid 1916 it had become usual to put even smaller groups of specialists out ahead of the already thinned assaulting waves. By the time of the battle of Arras in early 1917 a typical British company attack was formed of waves in which there were supposed to be about 6 yards between individuals. The first wave consisted of a single platoon, split into four sections – and two sections each comprised a separate line. This first wave was followed by some ‘moppers up’. The second wave was again one platoon followed by ‘moppers up’; and the third wave a further platoon. The nucleus of the fourth platoon was kept back at transport lines with any remaining men. Part of the logic of keeping back some troops ‘out of battle’ was that in the event of disaster there would be seasoned troops remaining on which to rebuild the company.

From the Bantouzelle sheet 57B S.W. 1, 1:10,000, with German trenches in red corrected to 19 May 1917. Here we see how a classic piece of Hindenburg Line defensive design has been combined with the St Quentin canal to maximum effect. The red hatching along the canal banks denotes flooded areas, crosses indicate obstacle zones. In front of Bantouzelle there are no fewer than three separate belts of wire, and these continue not only into the flooded area but also across the canal itself, the whole space being flanked by trenches and emplacements. A machine gun post is also placed at 90 degrees to the front to rake the streets of Banteux with enfilade fire. The front line is a double trench system, with not only another double obstacle zone between the first and second trenches, but also obstacles running along either side of the communication trenches, making them potential flanking positions – or enemy death traps.

However, the real firepower is to be found in the second line, squares ‘27’ and ‘33’. Here we see wire – three, four and even five belts deep – shaped into arrow bastions which will have the effect of channelling attackers into narrow zones which are swept by the heaviest fire. Machine guns are positioned not only in the fire trench but also behind yet another obstacle zone another 100-200 yards further back. The eastern half of square 27 alone shows 16 fixed machine gun posts – how many would have been missed by observers and how many weapons could be used in a roving capacity could only be guessed.

German field telegraphist of infantry regiment 452. Responsible for setting up field telephone systems the Fernsprecher Trupp usually consisted of an NCO and three men. Equipment of these troops included handsets, cable spools, transmission boxes, pliers, wire cutters, and as seen here on the soldier’s back, special poles. These Drahtgabel (literally ‘cable forks’) could be used to hoist wires into trees or onto telegraph poles. Several poles could be slotted together to obtain greater height. (Author’s collection)

A manual illustration showing a Royal Engineer with the cup discharger used for projecting No 36 Mills bombs in the latter part of the war. Note how the rifle is held upside down, allowing the shock of discharge to be transmitted directly to the ground rather than setting up stress in the butt. (Author’s collection)

It is commonly stated that the ‘Stormtroop’ tactics that eventually achieved major breakthroughs on the Western Front were introduced only by the Germans, and ‘invented’ essentially by General von Hutier on the Eastern Front. Though this makes for a dramatic story, and is useful as one more thing with which to castigate supposedly universally unimaginative Allied generals and tacticians, none of these things is actually true. Most, if not all, of the techniques displayed in Operation Michael in March 1918 had been used before, and by no means had every one of them been developed by the Germans – and those that were certainly did not appear suddenly, or in isolation. Perhaps the biggest myth of all was the development of the new trench-busting techniques on the Eastern Front. As Ludendorff himself stated:

On the Eastern Front we had for the most part adhered to the old tactical methods and old training which we had learned in the days of peace. Here [in the West] we met with new conditions and it was my duty to adapt myself to them.15

Indeed it may reasonably be argued that the resumption of mobility in the West was a function of a number of different tactical and strategic factors that developed over time. One point easily overlooked is that the latest defensive methods of 1918 no longer regarded continuous linear trench lines as essential to the defence. Though best perfected by the Germans, ‘zones’ of defence with reliance on machine weapons and artillery had become universally more important than trench ‘lines’ defended mainly by rifles. Similarly, artillery techniques and hardware, such as new types of shell and fuse, had reached new levels of sophistication – and suitability for use in shorter bombardments. The usefulness of the tank as at least a ‘breaking in’ weapon – if not a fully developed ‘breakthrough’ arm – has already been considered.

Finally, the good old-fashioned idea of weight of numbers also had a critical part in the resumption of movement on the Western Front. The revolution of October 1917 and the opening of negotiations at Brest-Litovsk spelled the end of Russia as an Entente partner. This allowed the Germans to achieve at least local and temporary superiorities of numbers in the West, at the very time that British politicians were unwilling to write Haig a blank cheque in terms of replacements after the bloody battles of 1917. During the spring and early summer of 1918 the wheel of fortune spun again, for whilst the Germans made very significant advances this was at the cost of heavy losses and further stretching of already perilous supply chains. Meanwhile US troop numbers, relatively insignificant the previous year, now built up to a level where American divisions were ready to mount their own offensive battles. French forces, degraded to the point of mutiny in 1917, now also recovered their composure. Taken together these factors helped to give the British in particular the local superiorities required for successful attack.

A gefallener Engländer of the North Staffords. Bodies were often searched – for identification as well as valuables – and boots were removed by the Germans as salvage. (Author’s collection)

The artillery techniques of short ‘hurricane’ bombardments, creeping barrages and fire without registration were not new. German artillery guru Georg Brüchmuller had been using them all for months or years, and creeping barrages in particular had been in use by the British and French, as well as the Germans, since at least 1916. Fire without registration had been a subject of experiment by the Royal Artillery in 1917 and generally dismissed as questionable. Map firing was now the norm, not the exception.

Corporal Amos Wilder of the US 17th Field Artillery described typical long-range artillery techniques of 1918:

When the camouflaged guns were in firing position in a given sector, orders would come by field telephone or courier from the Colonel at regimental headquarters to our Captain. So many rounds of either explosive or shrapnel shells at such and such times and such frequency. The targets were identified by coordinates on a grid map of the area which showed its features in great detail. Using the map our officers could determine the direction and distance of the target in relation to our position. Allowance had to be made, however, for such factors as atmospheric conditions as well as distortion in the maps themselves. Trial firings by our guns therefore needed to be observed from a forward position. Our telephone detail would string wires through the woods and fields to such an observation post. Instructing our gunners to fire, the officer would then note how far the shot was ‘over’ or ‘short’ right or left, and thus correct the following trial.16

The small unit infantry tactics of platoons and sections moving rapidly from cover to cover, working around enemy positions and making copious use of grenades, whilst directly supported by their own light machine guns, evolved – as we have seen – over a period of three years. Small units were deployed experimentally, and in raids, and various sorts of bomb squad and stealthy assault party were in action as early as 1915; the same year in which offensive techniques were developed for light flame-throwers. Light machine gun tactics were more advanced in the British Army than pretty well anywhere, and the French were also well aware of them though sometimes hampered by poor equipment. Aircraft co-operation was at least as advanced in the Allied armies as in the German, and the obvious piece of offensive equipment that the Germans were short of in 1918 was the tank.

In 1916 the reorganization of infantry companies as a combination of specialized groups had already begun. The French were arguably as advanced in this process as any nation. By the end of 1916 the standard French infantry company of four platoons contained as its fighting complement:

12 NCOs armed as automatic riflemen or bombers

12 Rifle armed NCOs

24 Automatic riflemen

68 Riflemen

28 Bombers

16 Rifle grenade men

8 Grenade carriers

Each of the four platoons was made up of two full and two half sections. The half sections comprised one with a corporal and seven bombers, the other, two Chauchat teams of three led by a corporal. The full sections were eight or nine riflemen each, backed by two rifle grenadiers and a grenade carrier – these full sections being led by sergeants. As far as possible individuals were taught more than one specialism, and all were trained to use the rifle and hand grenade.

Within the French battalion there was also a machine gun company, armed with not only eight medium machine guns but a 37mm gun for light close support. As an American commentary in the publication Notes on the Methods of Attack and Defense observed, ‘The battalion has thus come to be a very strong unit, capable of progressing by its own means, and of breaking most resistance it encounters.’ The organization within the French companies allowed the ‘introduction of new arms into the infantry without upsetting the organic channels of command as they are now established’. Whilst the specialists could remain within their sections it was also possible for the company or battalion commander to concentrate them for a particular tactical requirement.

For the British the introduction of Lewis gun teams with the infantry battalions in 1915, and the use of ‘Grenadier Parties’, had marked the beginning of a shift from lines to more flexible attacking tactics; but the idea that the platoon was the ‘unit of attack’ was not general until after the battle of the Somme. In February 1917 the important manual Instructions for the Training of Platoons for Offensive Action laid down a scheme for platoon organization somewhat similar to the French model. The British platoon was now to number from 28 to 44 with an ‘average strength’ of 36 in four sections. These sections were designated bombers, Lewis gunners, riflemen and rifle bombers, and each section was led by an NCO. Men with particular aptitude for shooting, throwing or scouting were to be allotted accordingly. The platoon ‘HQ’ was an additional four men led by an officer. Each of the weapons had something different to contribute. The rifle and bayonet – with which all troops were to be proficient – were defined as ‘the most efficient offensive weapons of the soldier’ and intended primarily for assault, repelling of attack, and ‘obtaining superiority of fire’. The grenade was the ‘secondary weapon’ of all, being ideal for ‘dislodging the enemy from behind cover or killing him below ground’. The rifle bomb was the infantry ‘howitzer’, attacking the enemy from behind cover and perhaps driving him underground. The Lewis gun, as ‘weapon of opportunity’, could kill the enemy above ground or drive him below. The fact that it was mobile and presented a small target made it useful to work round a flank or protect a flank.

Whilst Instructions for the Training of Platoons still assumed that major assaults would be launched in a series of rough ‘waves’ (not parade ground lines), there were many instances in which the platoon would be expected to operate as sections. In a ‘trench to trench’ attack, for example, the rifle section was expected to ‘gain a position on a flank’, attacking with both ‘fire and the bayonet’. The bombers with hand grenades would similarly and ‘without halting’ gain a position on a flank from which to attack. Meanwhile, the rifle bombing section was to lend support, gaining the nearest cover possible, and from here ‘open a hurricane bombardment’. The Lewis gunners were to take cover and open a ‘traversing fire’ upon the point of resistance, being later available to work round a flank. Though by no means general for all purposes, section-strong ‘blob’ and ‘worm’ formations were also in use by this time. For attacking in woods a ‘line of skirmishers’ was recommended, followed by small section columns. Under threat of artillery fire the platoon would also move as sections, in ‘fours, file, or single file, according to the ground and other factors of the case’.

Just a month later, in March 1917, Canadian 4th Division issued a memorandum instructing that it was ‘the mobility of the platoon’ and nothing else which could deal with the sudden and unexpected discovery of a machine gun. General Arthur Currie investigated French methods, as had been applied at Verdun, and concluded that capturing useful topography was a better aim than simply attacking trench lines. Moreover, careful training, particularly of companies and platoons, paid better dividends than the painstaking organization of ‘jumping off’ trenches and other somewhat predictable forms of preparation.

That the art of attack had moved on significantly was underlined by the instruction Assault Training, issued in September 1917:

Fire and movement are inseparable in the attack. Ground is gained by a body of troops advancing while supported by the fire of another body of troops. The principle of fire and movement should be known to all ranks, and the one object of every advance, namely to close with the enemy, should be emphasised on all occasions.

Assault training was now to be divided into three stages: training the individual in the ‘combination of rifle fire and bayonet work’; training in bullet, bayonet and bomb and the use of ‘the weapon appropriate to the situation’; and collective training in ‘all infantry weapons by means of a tactical exercise’. Departure from the start line was still ‘at a steady pace’ – but might include ‘firing from the hip’, and was to lead to a charge close to the enemy position. Some of the most advanced methods were borrowed from those of the scout, as is illustrated by an exercise given in Scouting and Patrolling of December 1917:

A group of men, covering each other’s advance, rush from cover to cover, a distance of 200 to 300 yards, to shell holes within 50 yards of the butts. Targets, stationary, representing Machine Guns or loopholes at longer ranges, moving figures at closer ranges. Dummy figures just in front of the butts. Scouts in the butts watch the advancing men with periscopes, noting the mistakes and learning how difficult a mark the good scout presents.

By May 1918 Hints on Training, published under the auspices of Lieutenant General Ivor Maxse, gave further indication of just how far things had changed. General principles of training were now to be ‘on simple lines’ and to cover the essentials. These were discipline, the importance of keeping direction, the ‘value of the bullet’, the use of ground, immediate counter-attack – and, perhaps critically, ‘fire and movement’. All tactical training at platoon level was to include the use of a Lewis gun, and training was to be designed ‘to interest, not bore’. Sections were now to comprise six men and an NCO, and all sections were to be trained first and foremost as ‘rifle sections’. Any section that fell below three was to be disbanded and reintegrated with others to provide viable units. Sergeants and corporals were to be trained to fulfil the roles of platoon commander in case of lack of replacement officers: ‘A battalion must be organized into 16 platoons and 64 sections. This is the basis of all training.’

Though bomb, rifle grenade and bayonet training were still part of the curriculum, the maxim now was that ‘the bullet beats the bomb and bayonet’. Rifle training was to concentrate on rapid loading, aiming and firing, with an expectation of 15 accurate rounds per minute. Where possible rapid loading could be used as subject for a competition, perhaps with one man attempting to load faster than another could empty a rifle. Practice for the attack was now to focus on objectives, covering fire by Lewis guns and machine guns, fire and movement, and liaison with units to the flank. The mantra for the attack was now, ‘When in doubt go ahead. When uncertain do that which will kill most Germans. Don’t fear an exposed flank. Teach the exposed flank to hang on, or to push out and protect itself.’ Somme veteran D. V. Kelly was just one of many convinced that the British methods had made ‘enormous advances’ between the opening of the Somme and 1918.17 ‘Tremendous’ artillery bombardments – poorly synchronized, but lasting days – gave way to shorter but cleverly planned efforts which did not disclose the objectives in advance. Advances in plodding waves by daylight were often replaced by movement or attack under darkness. Large daylight operations were commonly fronted by tanks.

As we have seen, changes to German infantry tactics commenced very early with the use of small grenade-armed Stoss and Handgranaten troops for specific actions, such as attacks on strong points or raids. Experimental units, or Versuchstruppen, for testing trench mortars, small ‘assault cannon’ and flame-throwers were started in March 1915. The unit that tested the Sturmkanonen under Major Kalsow and later Hauptmann Wilhelm Rohr subsequently became recognized as the forerunner of all ‘Stormtroops’. Following the barrage as closely as possible, and movement from shell hole to shell hole, were established techniques by the time of Verdun, as the account of a lieutenant of the 115th Hessian Leibgarde Infantry Regiment made clear:

I had already established with my people that ‘with the barrage we were out’. Everything then hung between life and death. The advance began immediately, creeping and jumping from crater to crater. A shell which struck on the edge of our crater showered my brave lad Franz at my side with stones and earth, but the effect was trivial. Forwards, only forwards, called my inner voice. My undaunted colleague Martin S. quickly found another hole and raised his rifle: we were beside him in an instant. Often we held craters only a few metres from each other, but without being aware of it in the crazy noise – bullets whistling over us, and amongst the roar of the arrival of shells.18

The damp subterranean central passageway of Fort Douamont. Outdated, but still a substantial obstacle, Douamont was arguably the most formidable of Verdun’s 19 major forts. Occupied by only a skeleton garrison it was seized by the Germans in an unexpected, and possibly accidental, coup on 25 February 1916. Repeated and bloody attempts to take it back followed. On 8 May several hundred German soldiers were killed in an accidental explosion and fire, stoked by hand grenades, a munitions dump and flame-thrower fuel. Following massive bombardment the French re-entered Douamont in October 1916. (Author’s collection)

New manuals for the weapons of close combat, Nahkampfmittel, issued in August 1916 and again in January 1917, stressed the role of grenades, pistols and close range work from one shell hole to another. There was also a widespread willingness on the part of commanders, generally unmatched in Allied armies, to allow latitude to juniors – to lead by ‘directive’, and target driven means, rather than prescription. Crucially, however, producing the new equipment required to re-equip the entire infantry arm, and to retrain it in new methods, would take a long time. Integrating small unit tactics with the bigger picture could also be problematic. Moreover, as Clausewitz had once remarked, ‘War consists of a continuous interaction of opposites’ – and many methods would evolve to perfection only through a process of trial and error, and of learning by observing enemy successes and failures. Some new techniques were also honed by the mountain troops of the Alpenkorps, where, by necessity, small gun batteries and machine gun units were attached at a low organizational level to the rifle-armed troops, and terrain offered opportunities for small unit actions on non-continuous fronts. So it was that for quite some time ‘shock units’ were just a small part of the army, drawn out from existing battalions and regiments to spearhead an attack or perform a specific role. This process was regularized in May 1916 when the High Command ordered that all armies on the Western Front should send cadres of officers and men to the new Sturmbataillon to learn techniques, and then return to their units to teach the latest ideas. By November most divisions, and many regiments, could boast at least one Sturmabteilung, or ‘assault detachment’, of company strength.

Arguably the full development of self-supporting platoons and squads was held back by heavy losses, the need to maintain a very long perimeter on two fronts, and a failure to fully realize Germany’s industrial potential until 1916. Nevertheless Stoss troops had been employed at Verdun, and the use of small detachments and infiltration techniques was well advanced by 1917. In August 1917, for example, German 451st Regiment launched an operation on the ridge of Hill 124 based almost entirely on the deployment of Stoss troops and ‘Storm companies’. The attackers were both special companies drawn from ordinary units, and detachments from a Sturmbataillon. Part of the force moved out of the German front line under cover of darkness, taking position from 80 to 220 yards from the French, and a second wave then occupied the jumping off trenches. The assault was supported by brief mortar and artillery fire, aimed mainly at the neutralization of French batteries, and the sealing off of the target area. The Stoss troops were under orders to seize the objectives, but to retire back on the German lines when other troops arrived to relieve them.

In September 1917 1st Bavarian Division prepared plans for a limited attack, or giant raid, in the Champagne – ‘Operation Sommerernte’ (Summer Harvest) – which was to integrate gas with no fewer than 12 ‘shock troops’ drawn from the division, three from the 2nd Sturmbataillon, and some specially formed ‘destruction’ and ‘salvage’ squads. Further shock troops from neighbouring divisions would also attack, leaving the enemy in doubt of the extent of the operation and reducing the possibility of enemy interference from a flank. There would be no drawn out advanced bombardment, but artillery and trench mortars would fire to ‘neutralize’ enemy artillery with shells and gas. As a document later translated by the Americans explained:

The role of the shock troops will be to open a passage through the enemy’s positions for the salvage and destruction squads, to break down the remaining resistance, to attain the objectives assigned to them, and to protect the salvage and destruction squads during their operations.

US official photograph showing Lieutenant V. A. Browning firing the machine gun invented by his father at Thillombois, 5 October 1918. The 1917 model .30 Browning was manufactured by Colt, Westinghouse and Remington, with 68,000 produced by the end of the war. (IWM Q70559)

A gunner major at the awesome breech of a 12-inch howitzer of 444 Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery, near Arras, 19 July 1918. The weapon weighed well over 20,000lb, and 20 tons of soil were loaded into its ‘earth box’ to counteract the massive recoil. The officer’s rank is denoted by the crown and three lines of lace on his cuff: a gold ‘wound stripe’ worn above his rank insignia shows that he has been wounded once. (IWM Q6873)

The individual shock troop units were of about 50 men each, led by an officer, and mixed together infantry and pioneers to match the tasks to hand. The basis of each troop was a light machine gun squad, bombing squad and attached specialists and riflemen. The majority were organized as follows:

From the infantry

1 Officer

3 NCOs

16 Men

5 Man light machine gun squad

2 Signallers

From the pioneers

1 NCO

4 Pioneers

3 Gas specialists

From the Sturmbataillon

2 NCOs

3 Pioneers

6 Grenadiers

2 Stretcher bearers

Towards the end of 1917, during the battle of Cambrai, British commentators noted German use of what were virtually fully developed ‘Stormtroop tactics’. As the Official History recorded:

Preceded by patrols the Germans had advanced at 7am in small columns bearing many light machine guns, and in some cases flame-throwers. From overhead low flying airplanes, in greater numbers than had hitherto been seen, bombed and machine gunned the British defenders, causing further casualties and, especially, distraction at the critical moment. Nevertheless few posts appear to have been attacked from the front, the assault sweeping in between them to envelop them from flanks and rear.

By the end of 1917 Allied intelligence therefore had quite a good idea of the latest German techniques. In the US this knowledge was summarized as ‘Tactics of the German Assault Detachments’ as part of the manual German Notes on Minor Tactics. The key factors identified were good advanced preparation; a brief but ‘very violent’ application of artillery and mortars which ‘caged’ the area under attack; and finally the actual attack of the Stosstrupp units. Their method was to advance ‘by groups, using the shell holes’ with the wings of attack having ‘reinforced groups’ for flank protection. Study of a specific action at Sechamp Woods suggested a model of a Stosstrupp that numbered 106 men, carrying with them two light machine guns and an automatic rifle. Probably in addition to some long arms, individuals were equipped with ‘a Mauser pistol, a trench knife, a bayonet, and in a sandbag 16 stick grenades and 8 egg shaped grenades’.

What was different about the German Spring Offensive of 1918 therefore was not the application of any individual technique, but its scale, reinforced by troops drawn from the East, the general equipment of the assaulting divisions to the latest standard with items such as new mortars and light machine guns, and the willingness of Ludendorff to take this all or nothing gamble to finish the war with a ‘Peace Offensive’. Also of significance was the existence of an overarching doctrine in the form of the new manual Der Angriff im Stellungskrieg – ‘The Attack in Position Warfare’. This document, published on 1 January 1918 under the authorship of Hauptmann Hermann Geyer, served to pull together all previous experience from all fronts into a general blueprint for the attack – not only limited attacks, significantly, but full-scale offensive battles leading from ‘position warfare to the breakthrough’.

The ‘New Armies’ – a soldier of the Durham Light Infantry in full marching order including the ‘large pack’, which was normally deposited before entering the trenches. Note the fearsome model 1907 ‘sword bayonet’ with its 17 inch blade, much of the time it was more of a weapon of morale than practical impact on the modern ‘empty battlefield’. The 1914 type leather equipment with its distinctive large pouches was a stop gap but never as popular as the 1908 webbing with its ten small ammunition pouches. (Author’s collection)

Preparation for the assault was to be thorough but subtle, so as not to give away time or place. The bombardment likewise would be intensive and include gas, with a view towards ‘neutralization’, but would not be so prolonged as to give the enemy the chance to react. Where the shells were aimed at trenches a density of one German howitzer battery was deemed desirable for every hundred yards of trench line. The assault would be an attack ‘in depth’, with each division so deployed that it had a frontage of 2,000–3,000 yards. Reserves were to be pushed in where there was success, not failure, and the keeping back of a portion of fresh artillery was seen as even more important than fresh infantry. Some of the lighter units, such as light trench mortars, would be designated as ‘accompanying artillery’, moving up with the infantry to fire at close range over open sights on arrival.

The infantry were to advance so hard on the bombardment that it was deemed preferable that they take casualties from their own guns, rather than appear after the enemy had any chance to recover. Assault detachments would as a matter of course lead the attack, but whether the main effort was ‘waves of skirmishers’ or waves of assault detachments was left up to circumstance. The battle was to be seen not so much as a matter of numbers as of comparative ‘fighting power’, that is, training and equipment, preparation and skill, ‘combined with rapid and determined action’. As far as possible the distance from the attackers to their objective would be minimized, the forces being gathered as far forward as practical in trenches, shell holes and dugouts. The effect of the enemy artillery response would be further reduced through surprise, and the fact that the first wave would be across the barrage zone before it could be badly hit. Subsequent reinforcing waves would be less dense and therefore suffer fewer casualties accordingly.

As Der Angriff observed:

Besides making full use of the weapons at their disposal and exploiting the enemy’s known weaknesses, the troops must have dash if the assault is to be successful. Success is gained by determined and reckless drive and initiative on the part of every individual man. A check in the attack in one place must not spread to the whole line; infantry which pushes well forward will envelop the parties of the enemy that are standing fast.