IN retrospect, the Tribals were an interlude. The high-low mix became impractical once the Royal Navy shifted concentration to the far side of the North Sea. Now all destroyers had to be suitable to operate on the far side of the North Sea.

Meeting to frame the 1908–9 Programme in June 1907, the Admiralty Board planned both a new class of destroyer and an unarmoured cruiser which was ‘urgently needed to act as parent vessel to the large and increasingly numerous flotillas of our Destroyers when operating on an enemy’s coast, as well as to meet the vessels of the same type now being built by foreign nations (more especially Germany)’. The Board decided on a twenty-five-knot cruiser with twelve 4in guns and endurance 50 per cent greater than that of Boadicea, giving it two more guns and 1.5 knots more speed than its German counterpart.1 The draft programme showed five such ships, and the figure six was pencilled in. The programme eventually produced only a single cruiser, the repeat Boadicea, HMS Bellona, and two more followed in 1909–10.

The destroyers were described as an improved type with ‘superior endurance and sea-keeping qualities to the most recent German destroyer’. The draft programme showed twelve such ships, the figure sixteen being pencilled in as part of a rolling-force modernisation programme. Including sixteen in the 1908–9 Programme would reduce the number needed in 1909–10 to twenty-four. The rise to sixteen became possible when the estimated unit price was reduced, the same £1.5 million provided for twelve destroyers in June was considered sufficient in November 1907 for four more ships.

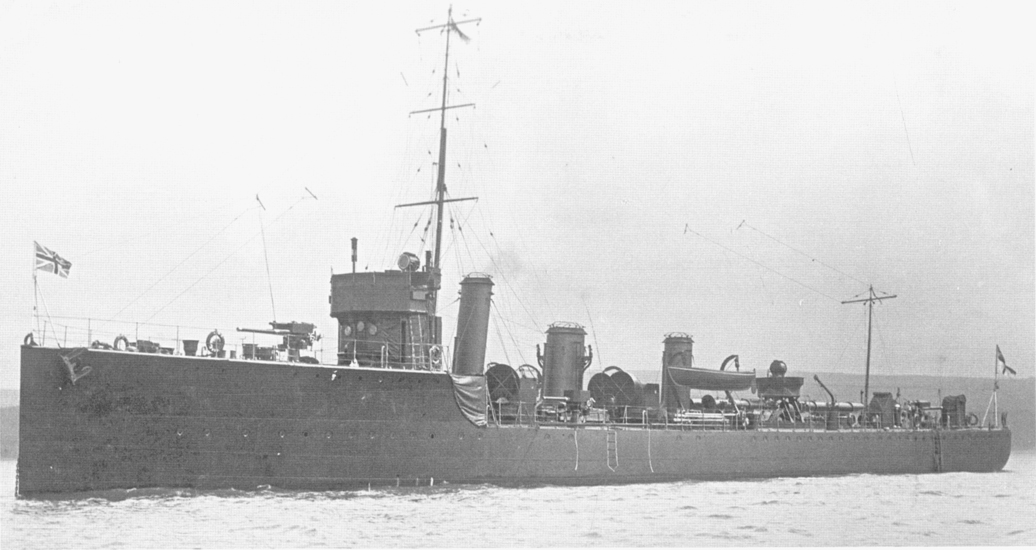

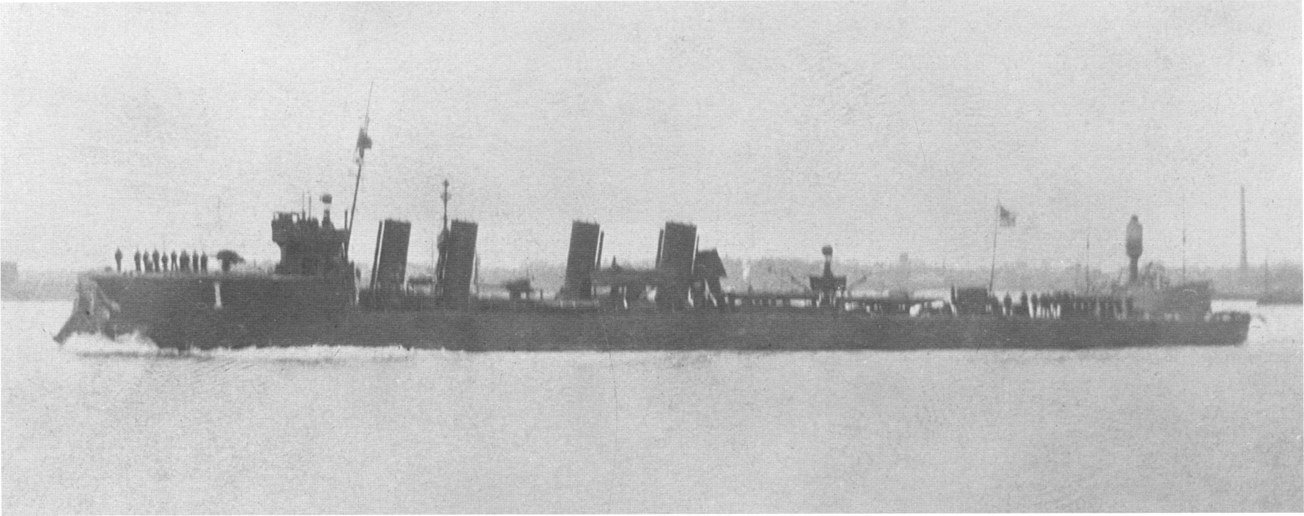

HMS Beagle was name ship of her class. These ships could be distinguished by the raised mounting for the forward 4in gun (originally it would have carried a pair of 12-pounders side by side). They were larger than their successors because of the inefficiency of their coal-burning boilers. The pole atop the bridge is for a semaphore.

Seen in 1918–19, White’s Harpy shows typical First World War modifications, such as a roofed-over bridge and a shielded forward gun. She retained all of her guns, but one single torpedo tube was landed. She had one 3-pounder Vickers antiaircraft gun. In June 1918, she carried fifty depth charges. She had two tracks, two throwers, four cages carrying reloads, and sixteen arbors for the throwers. The initial depth charge battery (1916) had been two charges in chutes. In October 1918, Beagle class destroyers operating in home waters were assigned two throwers and about thirty charges, the after gun and torpedo tube being surrendered as compensation. Beagle and Scourge alone carried four throwers and fifty charges. Of the surviving ships of the class, only Basilisk, Foxhound and Mosquito still had two torpedo tubes.

(US NAVY PHOTO, DONATED IN 1967 BY

PETER K CONNELLY AND WILLIAM H DAVIS)

In effect the new ships were the improved Rivers planned for the 1904 Programme and aborted in favour of the Tribals.

The Controller asked the DNC’s destroyer specialist (Pethick) to pay special attention to the new German 560-ton destroyer, which had her bridge further aft than in British ships and should therefore have been a better sea-keeper. The high reported speed of the new German destroyer also affected the design.2 Gun armament was initially to be five 12-pounders in place of the mixture of 12-pounders and 6-pounders in the Rivers and earlier ships.3

In January 1908, the Controller (Rear Admiral Henry B Jackson) provided some guidance to the DNC. He wanted draught and freeboard much like those in the Tribals (fifteen feet at the stem, with a good flare, and seven feet amidships; maximum draught should be seven feet). Trial duration should be six hours, again as in the Tribals. The Controller wanted oil fuel (but the ships ended up as coal-burners, to save money).4

The Commodore (T) pointed out that British destroyers would generally lie off the enemy coast waiting for his destroyers and torpedo boats to come out, so sea-keeping was much more important than maximum speed (Bayley thought a lengthened River capable of twenty-eight knots sea speed would be just right).5 Sometimes destroyers might have to retire under fire after penetrating enemy harbours. A retractable bow rudder would enable them to pull out stern first rather than take time to turn. Sea-keeping meant a high flared bow (and no turtleback) as in the Rivers, and an overhanging stern covering the rudder and lifting the ship out of the water in a following sea. It made for better steering in a quartering sea and it protected the rudder head. Sea-keeping also demanded the driest possible forebridge, hence as far aft as possible to minimise spray and waves which could blind helmsman and captain. In very heavy weather the ship would be steered from the conning tower beneath the bridge, which was no longer seen as a battle steering position. Bayley disliked the breakwater usually fitted on the forecastle because it turned waves into spray in the eyes of the helmsman and gun-layer. Existing bridges were too large, their size having been doubled by adding a radio (W/T) room – which would fall onto the guns on deck if its stanchions were shot away. It should be below decks. The Commodore (T) wanted a second searchlight aft, not blocked by the ship’s boats, to supplement the usual one on the forebridge. Ships should have a generator driven by an internal-combustion engine so that they could be lit internally when in harbour. Bayley wanted destroyers to be able to burn either coal or oil, but realised that would be a problem.

The DNC prepared a model showing the new type of bow planned. It offered as much flare as possible, although it could not have enough to lift a destroyer over large waves without dangerously straining her hull. The DNC initially offered a thirty-knot derivative of the River class, which he expected would cost £110,000 (720 tons – compared with about 580 tons for a River; 250ft (225ft) bp × 24ft (as in a River) × 8ft (7½ft), with 12,500shp engines). The sketch showed two 4in guns and two torpedo tubes, as in Tribals and Swift. Like a River, the ship would carry 130 tons on trials. In March 1908, the E-in-C asked whether it would be enough for the new destroyer to develop 60 per cent as much power as Cossack, during her full-power trials.

The Controller had something a bit less impressive in mind, with a speed of twenty-eight knots and an armament of four 12-pounders. Freeboard at the stem should be at least fifteen feet (with a good flare) and minimum freeboard at least seven feet, and extreme draught (over the propellers) should not exceed seven feet. The radius of action should be at least 1600nm at a speed not less than fifteen knots. The DNC offered an all-oil Design A and a mixed-fuel Design B, the latter verbally requested by Controller although the formal decision had been taken to to burn oil only. The DNC estimated that Design A would be 240ft × 24ft (770 tons) and would cost £106,000; Design B would be larger (270ft × 27ft; 980 tons) and more expensive (£130,000). In the previous year, the Board had decided to buy twelve destroyers for a total of £1 million, and each design would be too expensive (twelve ships would total £1.272 million and £1.56 million, respectively). The DNC’s figures were based on 12,000shp power plants sketched by the E-in-C. These sketch designs were completed about April 1908.

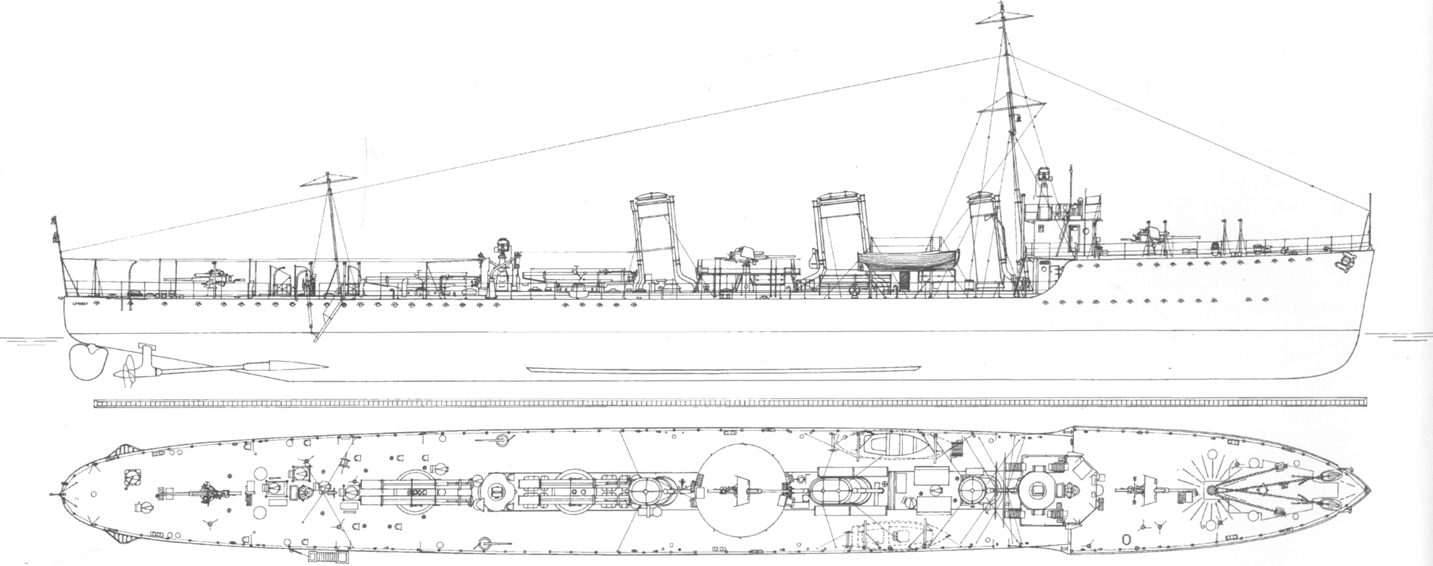

HMS Beagle HMS Beagle was a unit of the first class to be designed after the Tribals. She is shown in June 1910. As in earlier classes, these ships were built to different builders’ designs (Beagle was by John Brown), but the Admiralty imposed a standard general arrangement and armament arrangement. The decision to switch to coal-burning boilers (to cut costs) made it necessary to use five boilers (each of the two fatter funnels carried two uptakes), and the larger machinery space pushed deck features such as torpedo tubes aft. The boilers operated at 220psi, and the ship developed 14,333shp on trials (27.12 knots at 965 tons). These ships were unusual in British practice in having one of their two torpedo tubes right aft. As designed the ships would have had two more 12-pounders abreast forward, which is why the gun platform (for the 4in substituted for those two 12-pounders) was so wide. The Beagles were unique in having short 21 in torpedo tubes; note also the two reloads stowed on deck. The pattern of the brass ‘foot straps’ to port amidships was repeat to starboard with minor alterations to allow space for fittings. The open wooden decking around the after 12-pounder gun and the two searchlight platforms is only partially shown. Like other destroyers, these ships were fitted with increasing numbers of depth charges.

(DRAWING BY A D BAKER III)

HMS Fury was the Inglis version of the Admiralty Acorn class design. Note the 12-pounder alongside the second funnel, and the radio antenna spreaders aloft.

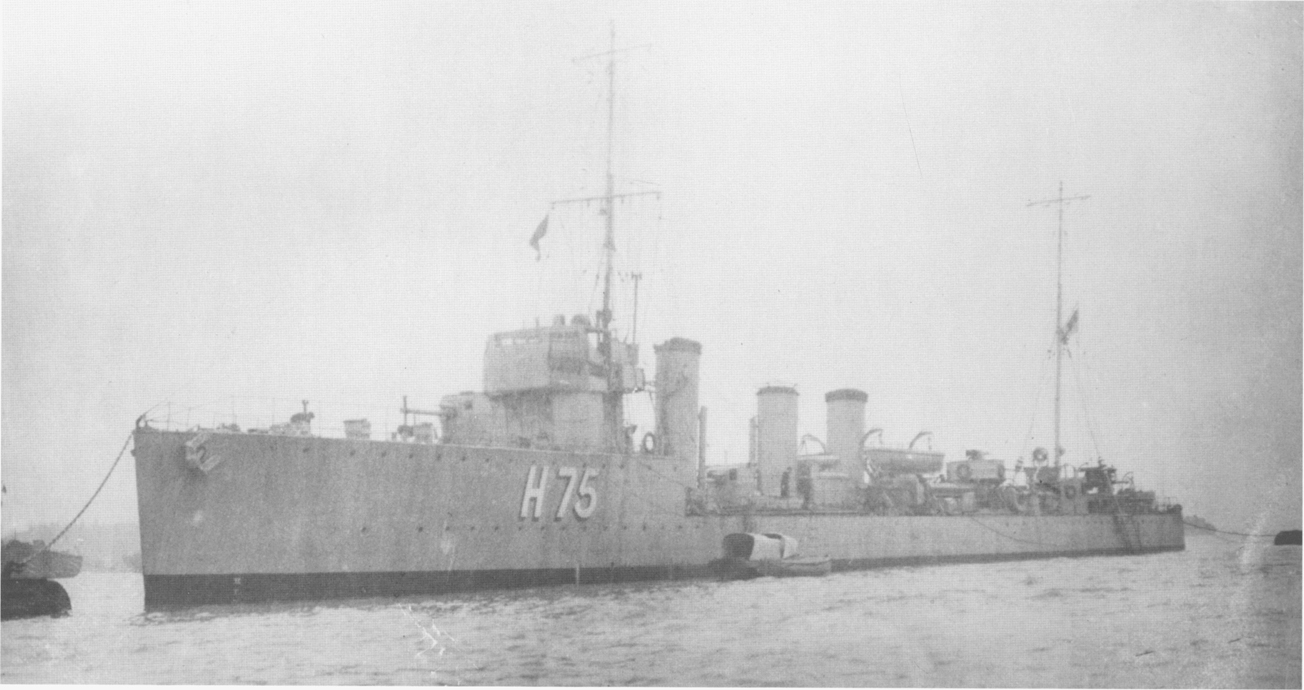

HMS Comet shows wartime changes in this 1918 photograph (she was torpedoed in August 1918). Her quarterdeck is filled with depth charges, and the after 4in gun has been relocated to the position of the after torpedo tubes. By this time ships of her class had been reduced to one torpedo tube, and her remaining tube was landed between October 1917 and April 1918. This photograph is somewhat puzzling because her H.25 pendant number was cancelled in 1916 when she went to the Mediterranean, where she was sunk. Apparently it was never painted out. In June 1918, HMS Brisk of this class had two throwers (four charges each), one depth charge track, and twenty-three depth charges; weight compensation included removal of one paravane crane and two depth charge chutes.

The guns were mounted two abreast on the forecastle and two abreast on the upper deck aft, the centreline being filled with machinery. Mounting guns abreast also increased firepower when chasing. Another two guns (total six) could be mounted in the waist. Alternatively, the guns at the ends could be mounted en echelon to increase the broadside. The DNC rejected the Controller’s suggestion that one torpedo tube be mounted between the funnels (to keep it as far as possible from the other) because it would have interfered with the fan cowls and stokehold hatches normally placed there, where they did not compromise the ship’s girder strength.

The Controller saw and approved this design. Bayley’s stern lengthened the ship about eight feet, which was acceptable. The forebridge could not be moved any further aft because of the position of the forefunnel. Destroyers designed (rather than modified after completion) for wireless already had their wireless offices below decks. The second searchlight had been considered and rejected in connection with the Tribals. Placing a torpedo tube between the funnels would be difficult. A lifting bow rudder would be practicable but would add considerable weight. Fuel would be oil only.

By May, the Board had settled on a sixteen-ship programme. As of 26 May, the Board hoped to approve the final design by 15 June, the DNC inviting tenders for hull and machinery at the end of August, and accepting tenders on 20 November. This schedule suggests that the DNC expected to produce a single design, since it seems that there would not be enough time to evaluate multiple designs. He was under intense pressure to get within the Board’s price range. On 3 June, the Controller asked for a ship to cost less than £100,000. To that end she would burn only coal, carrying two-thirds of her fuel on trial. Accommodations would be less spacious than in designs A and B. Guns would be mounted en echelon to fire across the deck, and the forefunnel would be raised to reduce smoke on the bridge.

The DNC’s destroyer specialist (Champness) pointed out the serious disadvantages of reverting to coal. The power available per square foot of boiler room would much decrease, and fuel weight would greatly increase (because the thermal content of coal is so much less). Heavier machinery would force up the size and cost of the hull, and the trial load would nearly double compared with that of a River (it would be seven times that in a thirty-knotter). Burning coal (with stokeholds lengthened to suit), Design A would produce only 75 per cent as much power as with oil. It would be difficult to stow enough coal, because only about one hundred tons could be abreast the boilers. The rest would have to be in a cross-deck space about fifteen feet long, imposing a serious structural load.

Champness estimated that for a four-boiler coal-burner with the width of boiler room used in Design A, the maximum displacement which could be driven at twenty-eight knots would be about 540 tons – allowing only an unacceptable forty tons for armament, equipment, and coal. With five boilers a 750-tonner could be driven at twenty-eight knots. On that displacement the ship could carry a third of the coal required for the radius of action. Carrying enough coal would reduce speed by 1.5–1.75 knots. The DNC (Watts) thought that if at least two such ships were placed with each firm, the Board’s desired average price could be attained.

The Controller now (11 June) accepted some reductions: twenty-seven knots with two-thirds fuel on board, and five rather than six guns (with two on the forecastle). Accommodation could be cut to that of the River class, if that would cut the ship’s size. Projected armament arrangement was six guns: two abreast forward, one to port ahead of one to starboard in the waist, and one right aft offset to port. The DNO (Bacon) decided to raise the forecastle guns to ensure that sights could be kept on a target despite pitching. The planned 18in torpedo tubes could be changed to 21in tubes if required. The wireless office was soon placed on deck to free accommodation space below it (the design was badly cramped). The DNO pointed out that an office below decks probably would be unable to operate on the destroyer wavelength (presumably the leads to the aerial strung between the masts would have been the wrong length). Watts and E-in-C Durston suggested that the full speed trial should be for four hours, as in other coal-burning destroyers.

On 22 June, the Controller accepted this sketch design C, with three funnels, the tops of which should be in line. It showed five boilers in three boiler rooms, the aftermost containing a single boiler and therefore of smaller (circular) section. The Controller asked that, if possible, the bridge be made lower and the funnels shortened to match. It was impossible to lower the bridge, so the funnels were raised. The Commodore (T) still wanted his second searchlight, which was placed abaft the after funnel. The design showed five guns: two forecastle guns on a low platform, the after gun offset to starboard, the after waist gun to port. The Controller approved the design on 7 July, and it received the Board stamp that day. The ship would displace 850 tons.6 Ships came out considerably larger. Thin protective bulkheads (half-inch Krupp non-cemented (KNC) armour) were added at both ends of their machinery spaces in the contracting stage.7

As before, each bidder produced his own drawing, which the DNC had to check. By this time, destroyers were about the size of the old torpedo gunboats. It was no longer obvious that the specialist builders had a monopoly on the relevant design skills; slight savings in hull weight were no longer decisive. The DNC argued that it was no longer so useful to invite separate sketch designs. Instead of arguing that his own staff was competent enough to design such ships, he pointed to the lengthy delay in awarding contracts as his staff checked each design, particularly its structural strength. The situation was particularly difficult because the Controller wanted the maximum possible number of bidders so that he could force down unit price. Some of the bidders had no destroyer experience at all; presumably they, too, had concluded that these ships were more like the larger ships they normally built. The DNC complained that simply checking the bids would require additional staff and overtime, and that even then the process would be delayed. The alternative was simply to limit bidding to the most experienced firms, because experience showed that they offered the best and least expensive designs; designs by firms with little or no experience required much work to make them acceptable. The Controller liked the idea of adding bidders to force down the price. He agreed that the DNC should design the next year’s ships. Builders might still submit their own designs, some of which the DNC accepted specifically to try out desirable new features.

Builders were John Brown (three)*, Denny (one), Fairfield (three), Hawthorn Leslie (one)*, Cammell Laird (three), London & Glasgow (one)*, Thames Iron Works (one)*, Thornycroft (one), and White (two)*. Asterisks indicate firms that followed the Admiralty arrangement, with the third funnel smaller than the others; the other ships had equal-width funnels.

Because the 1908–9 ships, the Beagle class, were obviously inferior to the Tribals, they were criticised as examples of Admiralty failure. However, with the abandonment of the (unpublicised) high-low policy, the only way to provide the required numbers was to reduce unit cost. Admiralty policy shifted to seeking twenty destroyers each year. The main modification to the new ships while under construction was substitution of one 4in gun for the two 12-pounders on the forecastle. This was done well after ships had been laid down; it is not clear why this decision, which echoed that for the later Tribals, came so late. In effect the Beagles were the prototypes of all later British destroyers through the first half of the First World War.

For the 1909–10 Programme, the DNC got full design authority and the E-in-C continued to demand individual machinery designs from the different yards, requiring only that they fit in the space and weight the DNC allowed. As a consequence, ships with the same hull design might still have different arrangements of funnels, reflecting different boiler arrangements. The Superintendent of Contracting complained in January 1909 that the previous year’s contracting had taken far too long. Invitations to tender went out 21 August 1908, provisional telegrams of acceptance on 10 October and confirmation letters on 14 November – but as of January 1909 no contract had been signed. These dates apparently concealed a lengthy process of negotiation in which the Admiralty succeeded in forcing down prices because of a slump in British naval shipbuilding for foreign powers.8 The Superintendent wanted to order ships in September 1909 and as a result of this, invitations to tender had to go out in May rather than in August.

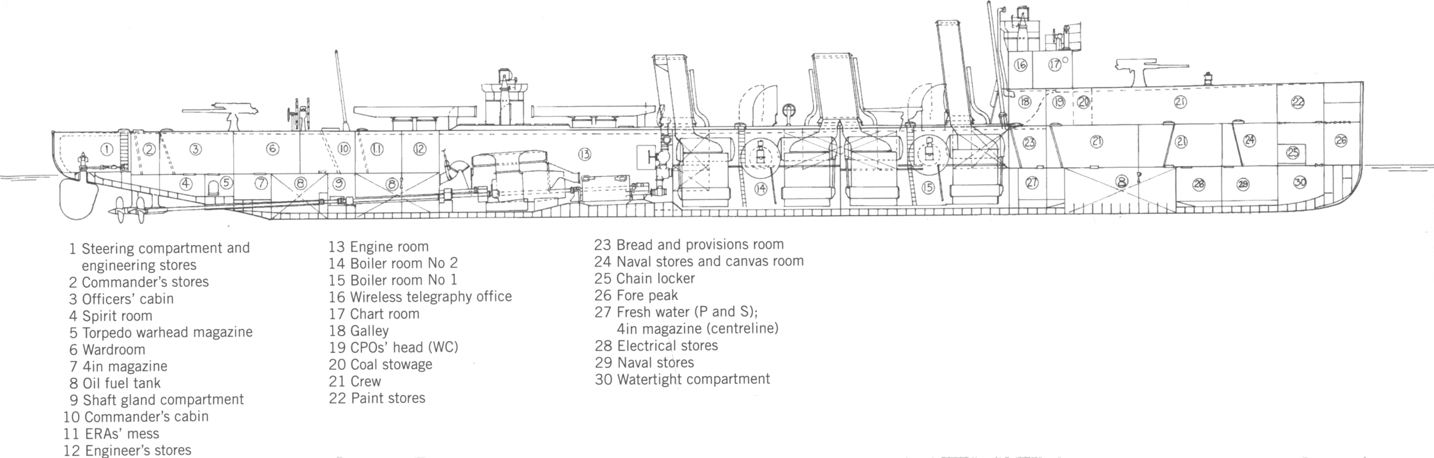

HMS Acorn The Acorns were the first British destroyers built to a standard Admiralty design. The name ship is shown as completed in 1910. These ships reverted to oil-burning boilers, so only four (220psi Yarrows) were needed. That cleared centreline space so that both (long) torpedo tubes could be amidships, with space for a second 4in gun on the centreline aft. Note the reload torpedoes stowed on deck. One reason a British destroyer carried fewer torpedo tubes than a foreign counterpart was that their torpedo tubes were much heavier, to the point that British officers were sometimes asked whether they were armoured. The forefunnel was raised during construction.

(DRAWING BY A D BAKER III)

Acorn INBOARD HMS Acorn shows the layout of the standard British destroyer design, as it developed through the early part of the First World War, with two boiler rooms (two boilers each, in this case). Acorn had two 4in guns on the centreline and two 12-pounders on the beam, where they could be supported alongside the boilers (which were on the centreline). The problem came when they were replaced, in later classes, by a third 4in gun. Unlike the torpedo tubes above and abaft the engine room, a gun needed substantial support. The two options, both of which were used in some ships, were to use the bulkhead between the two boiler rooms (in this case, below the middle funnel) or to run a gun support between two boilers (or to one side of a boiler). Ships with three larger boilers typically had two in one boiler room and one in the other, the one-boiler room being adjacent to the engine room to limit flooding if the ship were hit at the bulkhead dividing two spaces. Only in the First World War destroyers of the S and V & W classes was this principle reversed, to move the forefunnel and hence the bridge back as far as possible to keep it drier. The triple screws were typical of direct-drive turbine destroyers, whose propellers necessarily ran fast and hence inefficiently (geared-turbine ships all had twin screws; a few direct-drive ships did, too). Note too the large-diameter hand steering wheel of the emergency steering position aft.

(DRAWING BY A D BAKER III)

Work on the 1909–10 ships began with a 22 October 1908 memo from new the Controller, Admiral Jellicoe. Money would be even tighter, he thought, so he wanted unit cost cut to £80,000. To get there he would accept reduced speed (twenty-six knots) and even a reciprocating power plant. The ships could burn coal or oil. Armament would be at least three 12-pounders (the Beagles had not yet been given a 4in gun). Radius of action would match that of the Beagles. If the price limit could not be met, Jellicoe wanted to know what could be done. He did not yet know that during the protracted contracting process the Admiralty had succeeded in forcing down the prices of the Beagles below the estimated £100,000.

Work apparently began in March 1909 with estimates of machinery size and weight. Machinery so filled the hull of a destroyer that, once it had been settled, all other basic characteristics would follow. Armament took up so small a part of the ship’s displacement that the number and type of guns and torpedoes was quite secondary. The E-in-C saw Jellicoe’s ship as essentially a River and offered repeats of the coal-burning reciprocating and turbine power plants of HMS Usk and Eden, respectively, both of which had attained twenty-six knots on trial. He offered an oil plant with the same output and with one hundred tons of fuel, which he hoped would suffice for 1600nm at fifteen knots. The Controller soon decided to drop reciprocating engines, and the DNC’s destroyer chief (Champness) asked the E-in-C whether he could use the same turbines as in Eden. How much weight and space would oil fuel save? Without being sure of the size of the ship, Champness also asked for the weight of boilers and turbines producing 10,000shp, burning coal or oil. By the end of March, coal-burning had been abandoned, and the E-in-C noted that a 10,000shp oil-burning plant would weigh less than the less powerful plant aboard Eden, and occupy somewhat less space.

On the basis of model experiments using the form of HMS Cossack and a propulsive efficiency estimated from the trials of HMS Eden (which made 26.099 knots on trials), the DNC estimated that he needed 12,000shp. On 6 April, he told the E-in-C that he planned a four-boiler oil-burning ship (two boiler rooms) producing 12,000shp at 750rpm (Eden had run trials at 934.6rpm), the whole plant weighing 325 tons and 114 feet or 115 feet long. The E-in-C wanted longer boiler rooms, but offered to cut total weight to 305 tons.

HMS Jackal was a Hawthorn Leslie destroyer built to the Admiralty Acheron class design, with three boilers feeding two funnels. These ships were considered repeat Acorns. Note the funnel stripes indicating the ship’s identity (stripes indicating the flotilla were adopted postwar).

(PHOTO BY TOM MOLLAND LTD OF PORTSMOUTH

COURTESY DAVID C ISBY)

HMS Lurcher was a Yarrow ‘special’ (Firedrake type) within the Acheron class, HMS Oak, wartime tender to the Grand Fleet flagship, was of this type.

HMS Achates was an Admiralty Acasta class destroyer, the first group to have three rather than two 4in guns (in her case, abaft the boilers). This photograph was apparently taken before guns were placed aboard. Note the fold-down canvas strips on the fore side of the bridge.

Champness estimated that he needed a 310-ton hull (based on the River class), adding some hull weight to hold down stresses; the new ship would be somewhat wider and shallower. Given the E-in-C’s figures, he added seventy-five tons for oil and ten tons for reserve feed water, and 45 tons for armament and equipment, giving a total of 765 tons. Matching Beagle, he added two 12-pounders to the Controller’s original three, and also the desired long 21in torpedoes. This sketch design went to the Controller (a former DNO) on 7 April. By this time he had approved the 4in gun for the Beagles. Jellicoe therefore asked that the five 12-pounders be replaced by two 4in guns, the forward gun being raised on a platform like that in the Beagle class. He also increased trial speed to twenty-seven knots. The DNC added another two 12-pounders in the waist between the first and second funnels. Both of the two single 21in torpedo tubes were abaft the funnels. The four boilers were in three rooms, the middle one containing two boilers whose uptakes were trunked together into a wider funnel (the others were circular in section). Given the E-in-C’s comments, machinery weight could be considerably reduced, but it would be necessary to accept higher hull stresses.9 The design was arranged on the lines of the early Tribals, but it added half-inch KNC steel protective bulkheads at the ends of the machinery spaces, it offered the increased flare now desired, it showed the wireless office on the forecastle deck abaft the chart house, two searchlights giving nearly all-round coverage, and a wardroom and cabins for five officers. At the Controller’s request, one of the two masts originally planned was eliminated. The DNC thought he could come quite close to the Controller’s goal with a unit price of £82,000, but that was soon raised to £92,000, based on the costs of thirteen Beagles including necessary supplemental. The difference may also have been based on added power to achieve twenty-seven knots, not counted in the original figures.10 Weight-saving expedients included moving the engine room spares to the parent ship (tender) and moving the steering engine from the engine room to right aft (if that did not require extra personnel).

Jellicoe disliked the raised platform forward for the 4in gun because it acted as a breakwater, throwing up spray. The main argument in its favour was that without it the gun could not depress sufficiently when trained near the bow. By the time the detailed design went to the Board in July, the platform was gone. All 12-pounder ammunition was stowed in the forward 4in magazine and shell room, somewhat limiting what the after guns could do. One searchlight was in the usual position over the forebridge, and another aft over the engine room, raised high enough for its beam to clear the ship’s boats. Jellicoe saw no point in the protective bulkhead at the after end of the machinery spaces.

To cut costs, Jellicoe asked for a reduction to 26.5 knots at full power, and also asked about increasing endurance to 2000nm. He also wanted the after torpedo tube moved forward of the after 4in gun. Maximum cost was set at £88,000. To get 2000nm and keep speed at twenty-six knots would require thirty tons more fuel, and to stow that below the lower deck (as required) would require another sixteen feet of length – which was not needed for accommodation. The required power would rise to 13,500shp, hull weight would rise to 343 tons, machinery to 345 tons, and displacement to 822 tons – at a cost of £92,500. These estimates were completed on 30 April, to meet a 28 April request by the DNC. The legend showed a smaller ship (748 tons) making twenty-seven knots on 13,500shp. Jellicoe approved the design on 21 May, and the First Sea Lord (Fisher) and the First Lord (Reginald McKenna) approved it the same day. It showed two boiler rooms containing four boilers rather than the three rooms that the DNC had provided for the Beagles. In each the boilers were arranged with their furnace faces opposite, so that stokers could monitor both boilers in each room at the same time. Thus each room had an uptake at each end. The two middle uptakes were trunked together into a single casing, with narrower funnels fore and aft of them. The design showed three short funnels, all the same height. In the detailed version approved by the Board on 30 July 1909, trials displacement rose to 772 tons and radius at thirteen knots was about 2250nm rather than 1900nm. At this stage estimated cost was £82,000.

Twenty Acorn class were built. Brisk had twin screws driven by Brown-Curtis turbines; all the others were triple screw. Ships followed the planned funnel arrangement, but with the forefunnel raised six feet to reduce smoke on the bridge. On full power trials Acorn made 27.355 knots on 15,072shp at 745rpm (735 tons), suggesting just how approximate all of those horsepower estimates had been. Other ships did better; Larne made 28.723 knots on 14,900shp (720.2rpm), and Ruby made 30.335 knots on 16,776shp at 736 tons. Minstrel made 29.627 knots at 16,431shp (828.6rpm), and Sheldrake made 23.388 knots on 15,402shp at 786.7rpm.

In February 1910, the Controller (Jellicoe) told the DNC that of the twenty ships planned for 1910–11, fourteen would be repeat Acorns (‘new Acorns’). The other six would be ‘specials’ for which Yarrow, White, Thornycroft, Parsons, and John Brown were invited to tender. The latter held the license for Brown-Curtis, as opposed to Parsons, turbines. Brown had redesigned the Curtis turbine to improve its efficiency. The displacement, armament, form of bow, method of rudder attachment with type of steering gear, and factor of safety structurally were to be same as for the Acorn class. Otherwise they had a free hand to produce a boat of the highest attainable speed, which they had to guarantee.

A May 1910 legend showed triple-screw ships with the same armament and machinery, but slightly beamier (25ft 7in compared with 25ft 3in), displacing six tons more (778 compared with 772 tons). Estimated machinery weight was slightly reduced (303 rather than 310 tons) by using three rather than four boilers. As in the Acorns, two were in one boiler room (forward, hence not adjacent to the engine room). Trunking them together eliminated the funnel just abaft the bridge. It could be made substantially lower, giving the destroyer a less visible silhouette at night. Because this funnel badly smoked the bridge, it was raised during the First World War.

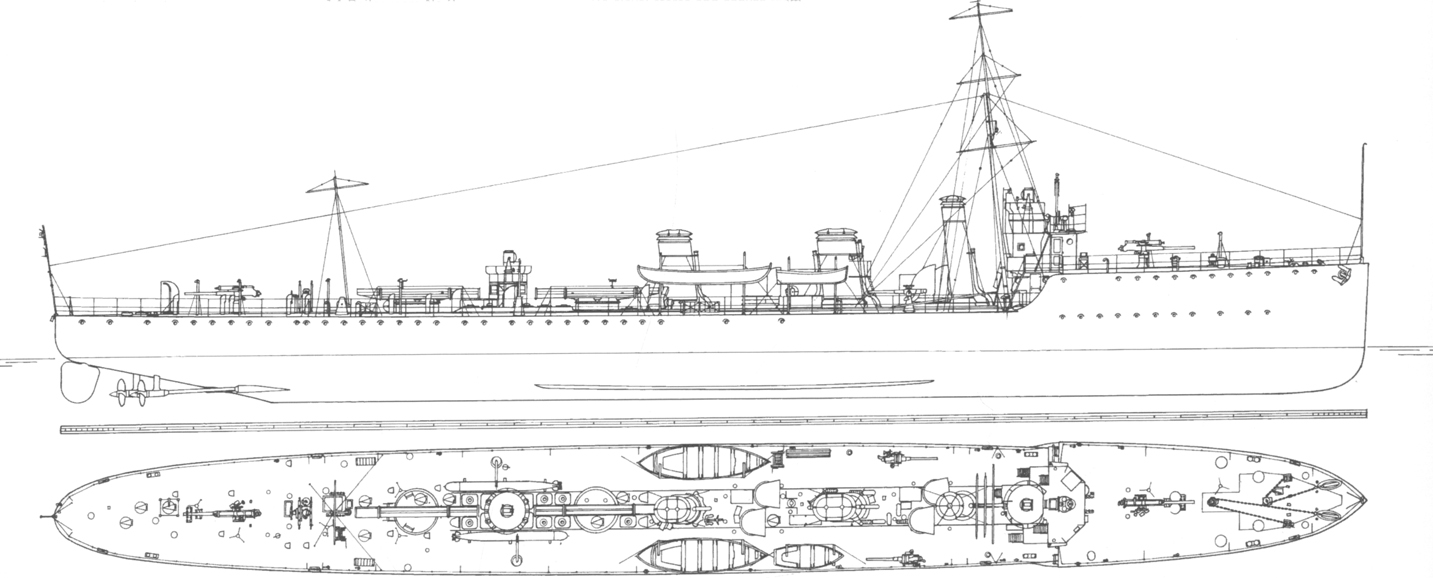

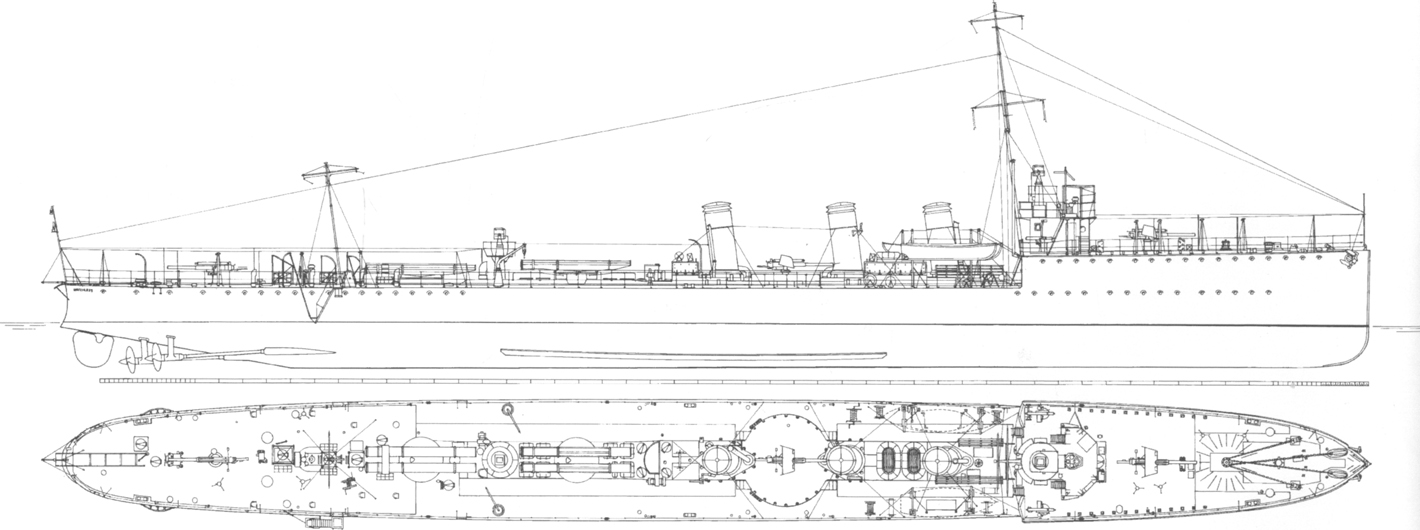

New Torpedo Boat Destroyers 1911–12 This Admiralty sketch design for the 1911–12 destroyers (K or Acasta class), dated 26 May 1911, was circulated to bidders. It showed four boilers (note the trunking in the middle funnel, and the line in the third funnel indicating that the uptake did not take up the entire width of the funnel) and two sets of geared turbines (24,500shp, twenty-nine knots). Dimensions were 267.5ft oa × 27ft × 9.25ft (1072 tons fully loaded). Armament was three 4in guns and two 21 in torpedo tubes (plus two reloads, one of which is visible abreast the second funnel). Designed range was 2750nm at fifteen knots. At this time standard practice was for bidders to offer their own machinery arrangements within the available space. For some reason hull but not machinery design was an Admiralty function, and the E-in-C commented on what sort of machinery he wanted but did not produce a design for builders to follow. Thus bidders could and did offer both direct-drive and geared turbines, and three or four boilers. The US Navy followed a similar procedure. This was the last class to have ventilating cowls for their machinery spaces.

(DRAWING BY A D BAKER III)

As before, the E-in-C evaluated different machinery arrangements offered by the bidders. The specials’ were offered with twin-screw plants – twin screws for simplicity and for its better manoeuvrability, as the two shafts could be run separately. These designs had no cruising turbines (normally on the centre shaft only). The E-in-C therefore recommended that ‘a fair proportion’ of the ships have two shafts. The DNC countered that their larger-diameter propellers added at least a foot of draught, an important consideration for ships operating close inshore. Since the ‘specials’ would provide experience with twin-screw plants, he wanted only two or four of the Admiralty boats to have them.

The Controller bought three Admiralty two-shaft ships, all from John Brown, whose more efficient turbine design might make up for the lack of cruising turbines. The other ships went to builders offering Parsons turbines, because of the high cost John Brown charged for its engines.

The six specials were ordered before the Admiralty boats: two from Parsons, built by Denny (Badger and Beaver); two from Yarrow (Attack and Archer); two from Thornycroft (Acheron and Ariel). Yarrow and Parsons both offered hulls about the size of the Admiralty boats (240 feet long); Thornycroft’s was longer (251ft 9in) and somewhat beamier (26ft 4in compared with 25ft 9¾in for Yarrow and 25ft 7in for Parsons) but with slightly less power (15,500shp rather than the 20,000shp of the others). Thornycroft’s design displaced more (830 tons compared with 780 or 790 tons, respectively) and drew more water (8ft 7in compared with 7ft 10in in the others). Guaranteed speeds were, respectively, thirty, twenty-eight, and twenty-nine knots. The two Parsons (Denny) ships had semi-geared turbines: extensions of the shafts of the low-pressure turbines were geared to fast-running small-diameter high-pressure and cruising turbines, transmitting up to 3000shp to the larger low-pressure units. The E-in-C expected better economy and smoother running, at a cost in greater complication and smaller blade clearances for the small highspeed turbines.

Three more destroyers of Admiralty Acorn design were planned for the New Zealand unit of the Royal Navy, paid for by the Imperial government (Canada was considering buying destroyers of its own at about the same time).11 By mid-1910, information had been received that the Germans were building thirty-two-knot destroyers. Their later ships would probably be faster. Money earmarked for the New Zealand ships was instead spent on three further ‘specials’ for the design of which the two specialist builders, Thornycroft and Yarrow, would have a freer hand. Reportedly, the information about the Germans came directly from Sir Alfred Yarrow.12 Yarrow may have offered an unsolicited proposal. The DNC check of the hull strength of the Yarrow proposal was dated 22 June 1910. A draft letter of acceptance was dated 1 November 1910, but on 26 November Thornycroft offered its own design (Design 6009, which was possibly a modified version of an earlier submitted design).13 Yarrow’s bid was far below Thornycroft’s, the difference sufficient for the Admiralty to pay for the necessary increased scantlings without reaching Thornycroft’s. After Thornycroft’s thirty-three-knotter lost to Yarrow’s thirty-two-knotter the company asked to be allowed to reduce to thirty-two knots and to reduce its price accordingly. Instead the Admiralty asked Yarrow how much more it would charge for a thirty-three-knotter of its own. Even that was far less expensive than Thornycroft’s design. Yarrow’s 255-foot Firedrake developed 20,000shp with three boilers (two funnels). She displaced 780 tons like the earlier Yarrow special, but she was not as beamy (25ft 7in) but drew more water (eight feet). On trials, Firedrake made 33.17 knots at 774 tons on 19,174shp.

In a December 1910 memorandum for the Controller, Captain Superintending Torpedo Boat Destroyers Wilmot Nicholson prioritised destroyer requirements: gun armament; speed and seaworthiness; low cost; and good radius. Because fights with enemy torpedo craft would be short, QF guns were vital: 4in QF rather than breech-loaders, or at least twice as many 12-pounder QF.

Nicholson doubted that a destroyer could be driven at over thirty knots in the North Sea on one day in three, and even then half the time it would be useless due to spray and similar problems. The Acorns had been designed for 13,500shp, but surely there would be no great difficulty in attaining 17,500–18,000shp, which should give a trial speed somewhat over twenty-nine knots. Seagoing speed when fully loaded should be about two knots less (adding seventy-five tons would cost about one knot). Although the advertised trial speeds of German destroyers were over thirty-two knots, ‘fairly reliable information’ gave their sea speed as about twenty-six knots. Nicholson was much opposed to seeking greater speed by unduly increasing size or unduly reducing scantlings (hence seaworthiness), ‘but if another three knots or say thirty-two knots on trial could be obtained by increased efficiency of motive power I think it would be desirable’. Nicholson suggested a maximum length of 255 feet.

Porpoise was Thornycroft’s version of the Acasta design. Like the Admiralty ships, she had her second and third 4in guns right aft. After the First World War, this ship was sold to Brazil. The Washington Treaty precluded the possible sale of many other surplus British (and other) destroyers, the sole other foreign sale being HMS Radiant, to Thailand. The clause involved was intended to prevent circumvention of the treaty by retention (by allies) of larger ships slated for scrapping, but it also prevented the collapse of the postwar warship-building market. This builder’s model is in the Science Museum, London.

(N FRIEDMAN)

Nicholson referred to a recent Thornycroft design intended to reach thirty-three knots, but armed only with 12-pounder guns. It was probably a version of the design Thornycroft had just offered unsuccessfully for the recent special destroyer programme (he was clearly unaware of Yarrow’s Firedrake). The NID produced a list of foreign destroyers showing that several foreign navies (Germany, France, the United States, Japan, and Argentina) were building large destroyers capable of exceeding thirty knots.14 It was reported that the Russians were about to lay down four thirty-five-knotters, each displacing 1000 tons.

In connection with the new design, on 31 January 1911, the DNC asked its test tank to try a destroyer hull form at speeds of ten to thirty-five knots. Later, the DNC asked for a curve for a ship 20 per cent deep, that is, at 1020–1030 tons. These figures give some idea of what was being developed.

The DNC submitted a sketch design to the Board on 6 February; tenders were expected in April. Yarrow’s thirty-two-knotter Firedrake rather than Acorn became the baseline, the new class sometimes being called the new Firedrake (repeat Firedrake). Like Firedrake, the ship was intended to reach thirty-two knots on trial at the usual trial load. However, early in the design process the trial condition was redefined as full load. That load was greatly increased because the desired radius of action was increased. Fuel load grew from 170 tons to 200 tons and then to 250 tons, so trial load increased from the 122 tons of an Acorn to 130 tons and then, when the basis for trials changed, to 310 tons. The Acorn trial load sufficed for 1000nm at thirteen knots; initially, the few extra tons in the new ship would have allowed her to make this distance at fifteen knots. On her full fuel load an Acorn could make 2750nm at thirteen knots. The new ship would have that range at fifteen knots, and could make 3650nm at thirteen knots. Given the heavier load, trial speed was cut to 29.5 knots (tank tests showed that was equivalent to thirty-two knots at the lighter load initially planned). The only weight compensation was elimination of the armour bulkhead at the fore end of the machinery, a step already approved.

Christopher ex Kite HMS Christopher (July 1914) shows how the 1911–12 design came out in practice. While she was building, the letter designations were applied to destroyers, and a series of ‘K’ names was proposed – and then abandoned (she would have been renamed Kite). Two of the three 4in guns were well aft (where a single hit would have disabled both) because the DNC and the E-in-C did not want to place a gun support column inside a boiler room, and because the obvious position atop the bulkhead between the two engine rooms was taken up by the middle funnel. Since the middle gun occupied centreline space which might otherwise have accommodated a torpedo tube, the forward tube was placed between Nos 2 and 3 funnels. Like previous destroyers, Christopher was completed without gun shields. She carried two reload torpedoes on deck, which are not shown. In April 1916, Admiral Jellicoe asked that eight destroyers have one 4in mounting converted to high-angle. That applied to HMS Christopher and to seven sisters: Acasta, Cockatrice, Contest, Garland (with QF guns, apparently not modified), Hardy, Midge and Spitfire. Garland was trials ship (September 1916), the gun being mounted on a trap door that could tilt up to fifty degrees to add to the gun’s elevation. Ships which did not have a mount converted were fitted with a single 2-pounder pompom. In April 1918, Christopher and others landed No 3 (high-angle) gun to clear the quarterdeck for depth charges and paravanes (the high-angle gun was retained at that time only on board Hardy, Midge and Spitfire; all of the ships with BL guns were reduced to two guns). Christopher also surrendered both torpedo tubes, as did Achates, Ambuscade, Cockatrice, Owl, Garland, Porpoise and Unity. Acasta and Owl had the high-angle guns and existing torpedo armament removed and two twin torpedo tubes fitted when attached to HMS Vernon, the torpedo training and experimental establishment. Achates and Owl were both assigned special (ie, heavy) depth charge armament, their after guns and torpedo tubes to be removed as weight compensation. Owl had a fish hydrophone (with a silent cabinet abreast the galley) and thirty depth charges: four throwers (four charges each) and two rails. In addition to her two 4in guns she had a 2- pounder pompom over the engine room, plus a Maxim. She carried no sweeps. Unity was a kite balloon ship. In October 1918, Christopher had all three 4in guns (none high angle) but still no torpedo tubes. Acasta also had three guns, but would have the two twin tubes as tender to Vernon. Owl was no longer assigned any sort of special armament, but Achates had the special depth charge battery, with her after gun and her torpedo tubes ordered landed.

(DRAWING BY A D BAKER III)

HMS Garland, a Parsons ‘special’, is shown shortly before the First World War at Netley, wearing her class (K) letter. Note the two 4in guns aft.

HMS Sparrowhawk was a Swan Hunter Acasta.

Adding oil and an extra (rather than two, as Nicholson wanted) 12-pounder aft on the centreline stretched the ship another five feet, to 260 feet. She displaced more (860 tons, later 870 tons). Given the extra load, the ship needed much more power (25,000shp, later 24,500shp). The E-in-C pointed out that the ship would need much lighter machinery than in the past: 34.3lbs/shp. The best to date was the 35.8lbs/shp in Firedrake. These were, however, design figures, and ships often did far better on the basis of trial performance (Crusader, the most spectacular, exceeded her designed power by 61 per cent). Power output depended heavily on how much oil was burned per square foot of heating surface. Admiralty contracts limited it to a conservative 1’1.05lbs per square foot, but Yarrow wanted to burn a quarter more in Firedrake. Given the possibility of gaining a quarter more than rated power, the E-in-C felt reassured that the new ships would not need unreliably lightweight machinery.

In February 1911, the DNO pointed out that recent tests had shown that a single 4in shell had roughly the effect of four 12-pounder shells. The 12-pounder did fire faster, but recent tests showed that the 4in made nearly as many hits per minute. One 4in gun was about equivalent to three 12-pounders at the expected short range. Replacing the three 12-pounders with a third 4in gun would save fifteen men. All three guns should be on the centreline, where they could be fought even in rough weather. This change was approved before the design went to the Board. In the last seven of the new ships DNO’s new QF 4in gun replaced the earlier breech-loading (bag) weapon. It was expected to match the 12-pounder firing rate. The DNC and the DNO argued that arming an 870-ton British destroyer with three 4in guns was reasonable, given that 950-tonners already being built for Argentina had four of these.

The problem was where to mount the third (roughly amidships) gun, because it was difficult to work in gun supports through a boiler or engine room, and machinery filled the middle of the ship. A boiler room position would be the worst, but a position over the engine room would make it difficult to unship turbines for repairs. The choice was to place the additional gun well aft, where earlier ships carried a torpedo tube, accepting that its blast might interfere with the searchlight there. The aftermost gun was shifted further aft to keep the two about forty feet apart.15

A four-boiler plant was adopted after the First Sea Lord, Admiral A K Wilson, warned against unduly forcing machinery (a higher rate of forcing was to be tried in HMS Savage, which was Thornycroft’s Beagle). The boilers were arranged as in the Acorns, with two narrow funnels and one wider trunked funnel, and the forefunnel raised to keep smoke out of the bridge. Unlike the earlier class, these ships had the forward torpedo tubes between the second and third funnels, rather than abaft the funnels. Adding the boiler lengthened machinery about 8.9 feet, the ship gained about twenty-five tons at a net cost of 0.4 knot in trials speed (the First Sea Lord approved twenty-nine knots). Since oil could not be stowed under the boilers, this extension cost fuel capacity. To some extent that could be balanced by adding peace tanks abreast the boiler rooms.

HMS Legion was a Denny Admiralty L (Laforey) class destroyer, her fatter middle funnel indicating that she had four boilers. Note the bandstand and covered form of her middle 4in gun, between Nos 2 and 3 funnels rather than aft. The gun was supported by a pillar in the after (of two) boiler room, between the two boilers in that space. In the previous Acasta class the middle gun was abaft the engine room.

Presenting the new design to the Board on 13 March 1911, the Controller (Admiral Charles J Briggs) pointed out not only that foreign destroyers were becoming faster, but also that some foreign (German) second-class cruisers, which would normally chase destroyers, could sustain more than twenty-seven knots. Some already building were designed for twenty-eight knots. Acorns would find it difficult to keep their distance from such ships even under favourable conditions. However, Acorns were not as inferior as might be imagined. The jump in rated power from 13,500shp in Acorns to 20,000 in Firedrake was not as dramatic as it seemed. On trials, ships regularly produced far more power than their rated outputs. If they produced 17,000shp, Acorns with oil tanks full would make 27.5–28 knots, compared with 29.5 knots for the new ship. All such figures were to some extent guesstimates. Model tests showed how much power (effective horsepower: ehp) had to be transmitted into the water. Turbines put out shaft horsepower (shp). How much of that went into ehp depended on the propulsive coefficient – which was difficult to estimate.16

The new ship was expected to cost £95,000.

It was assumed that specials would be ordered in addition to the Admiralty design, and the Controller promised the Board that they would not be allowed to exceed the 260 feet of the Admiralty ships. Wilson approved the sketch design on 7 April, and First Lord Reginald McKenna decided the next day that twelve ships would be built to Admiralty design and eight to special designs, one of which would have internal-combustion engines (Hardy). The legend received the Board Stamp on 12 June 1911.

All successful bidders offered two-shaft turbines. Geared turbines were offered, but the E-in-C decided not to adopt geared turbines pending trials with Badger and Beaver. On full-power trials in the Firth of Clyde, on 16 May 1913, John Browns Ambuscade made 30.636 knots on 25,595shp.

HMS Nicator was a late Admiralty M class destroyer, essentially an improved Laforey with No 2 gun moved to between the second and third funnels. They had three boilers (note the three equal funnels). The forward boiler room contained two boilers, the after one (forward of the engine room) one. The initial M class had straight stems and dispensed with gun platforms. Wartime repeat ships had raked stems and gun platforms. Bridge searchlights were generally eliminated in favour of remote-controlled searchlights aft. The tub visible aft carries a light anti-aircraft gun. All M class destroyers had three screws driven by direct-drive turbines.

(PERKINS)

Among proposed specials, the E-in-C liked Thornycroft’s tenders better than any of the others, so he recommended ordering at least three, preferably four ships (which was done). To him the two best other designs were those by Fairfield and Parsons. Because it was also interested in the diesel project, Thornycroft developed designs in which diesel engines or mines occupied the same compartment. When the DNC accepted this design, he asked that anti-roll tanks occupy this space. Mine stowage was rejected because steam pipes passed through this space. This was the shortest (257 feet) and lowest-powered (21,300shp; thirty-one knots) of Thornycroft’s four alternatives. Its other special feature was that the midships 4in gun was placed over the engine room – a position that the DNC disliked but had to accept.

Single specials were bought from Denny, Fairfield, and Parsons (hull by Cammell Laird). The DNC was interested in Denny’s longitudinally framed hull, which might be attractive for future construction. He considered the Denny ship very well designed, and remarked that Denny had invested heavily in research, building its own testing tank. Unlike the other ships of the 1911–12 Programme, Denny’s Ardent had three boilers (hence two rather than three funnels), her middle 4in gun being mounted between them above the bulkhead between the two boiler rooms. Fairfield also offered a three-boiler design, but with three funnels. Fairfield’s HMS Fortune had increased flare, hence a clipper bow. Parson’s Garland had semi-geared turbines in the standard Admiralty hull.

The Admiralty was already interested in a diesel destroyer, at the time called the ICE (internal-combustion engine) ship. The first proposal to install a diesel in a surface ship was apparently made in 1904. When the old torpedo boat TB 047 needed major machinery repairs (including boiler retubing), it was approved to replace her steam plant with internal-combustion engines, with £12,000 included in the 1906–7 Estimates (and retained in 1907–8 and in 1908–9). Tenders received from several British firms were disappointing, and the only British diesel maker, Mirrlees Watson, declined to tender. By September 1910, two-cycle diesels had made considerable progress, and the idea was revived (by this time TB 047 had become a target). The E-in-C (Oram) asked for £15,000 to install a four-cylinder 600bhp engine.

Now Thornycroft and Yarrow proposed mixed-power destroyers. Yarrow saw the diesel as the engine of the future, offering two-shaft Curtis turbines (for high speed, twenty-seven knots) and one- or two-shaft diesels to cruise at thirteen knots. The machinery space would be twenty-six feet longer, the ship 20ft 3in longer and eighty tons heavier, but she would have six times the range of a conventional destroyer. A third 4in gun could be mounted over the diesel compartment. Thornycroft thought it could squeeze in diesels (to cruise at fifteen knots) with 7ft 8in more machinery space (total addition of 11ft 9in to an Acorn) at a cost of at least fifty tons, to double or triple cruising radius. The E-in-C was interested, although he pointed out that even with the diesel running the ship would still need a small auxiliary boiler (eg, to generate electricity). Neither proposed design was worthwhile on its own merits, but a test ship, preferably Yarrow’s, would buy valuable diesel experience. The Superintendent of TBDs warned that in wartime a destroyer would always keep her boilers on line so that she could quickly accelerate to full speed.

HMS Mentor was Hawthorn Leslie’s special version of the M class, with four boilers and four funnels. In this 1915 photograph, the ship has had her bow crushed, but is otherwise undamaged. The significance of the Roman numeral / on the bow is unknown, since she was presumably part of the 3rd Destroyer Flotilla operating from Harwich.

(NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM)

The idea would have died, but in January 1911, Thornycroft asked what action was being taken on its mixed-power proposals. The E-in-C considered that neither firm’s proposal was entirely satisfactory. Since he still wanted to gain experience with diesels larger than those in current submarines, he suggested asking both firms to submit designs for the 1911–12 Programme with sufficient diesel power for fifteen knots (maximum speed would be thirty-two knots, as in the destroyers), and length should not exceed 260 feet, as in the destroyers.

On 4 March, Thornycroft offered a new design similar to their previous design. Steam turbines would drive two wing shafts, Sulzer diesels (total about 1800shp; eight cylinders total) in a separate compartment driving two centre shafts for cruising. This was the basis for its ‘special’. The DNC accepted Thornycroft’s bid (the First Lord approved the choice on 14 June 1911). Because the planned diesels were not ready in time, HMS Hardy was completed without them. She had the same 21,000shp steam plant as the other Thornycroft specials.

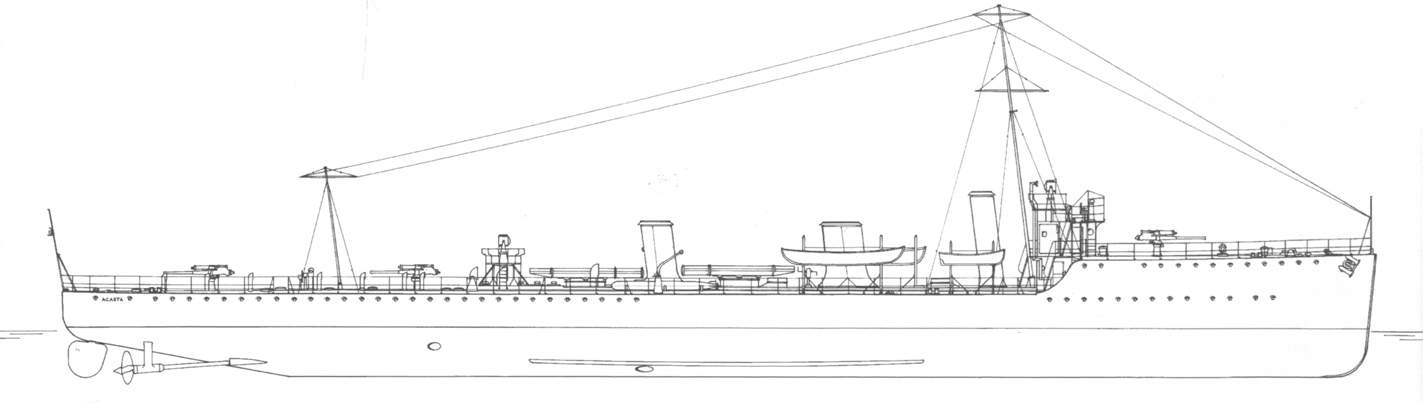

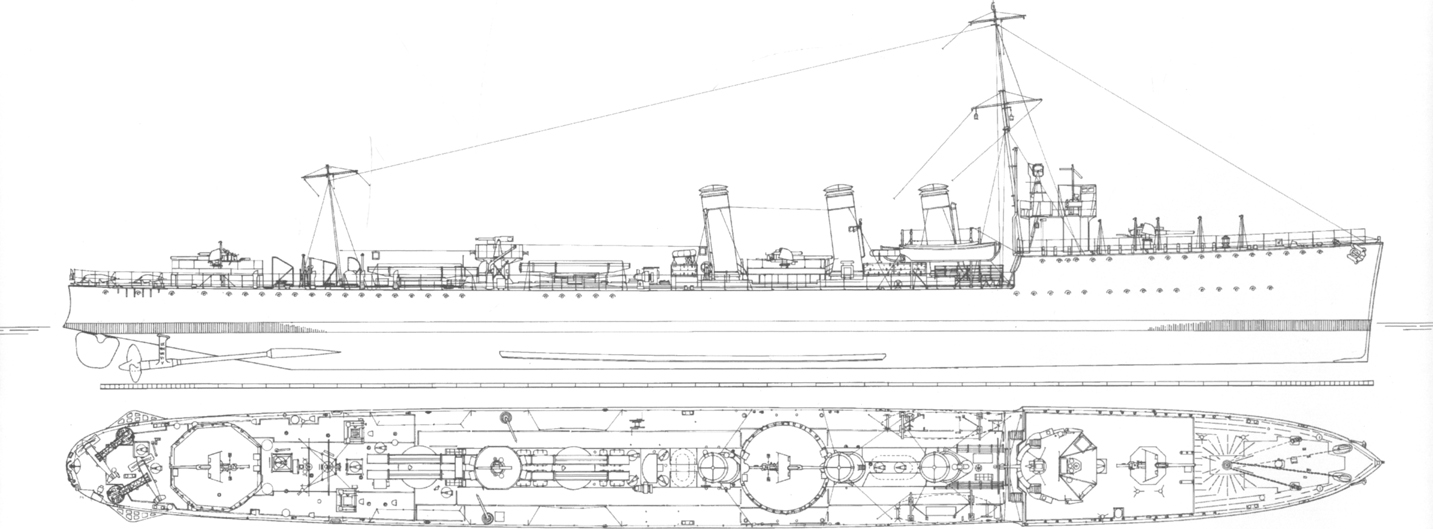

Laforey The L class destroyers were the prototype for the Royal Navy’s main series of First World War destroyers. Laforey is shown newly completed (19 February 1914). In this class the middle gun was finally moved amidships, in this case using a support column passing between Nos 3 and 4 boilers (the fatter middle funnel carried trunked uptakes from Nos 2 and 3 boilers in separate boiler rooms, so the bulkhead between the boiler rooms could not be used as a gun support). Single torpedo tubes were replaced by twins, the standard wartime arrangement, and two of the three 4in guns were given the shields shown, which became the First World War standard. Power was provided by four 250psi Yarrow boilers, and the ship had two direct-drive turbines. On trials, she made 29.95 knots on 25,128shp at 1112 tons (her full load displacement). This was the last class of destroyers for which the rated speed was at full load. The first war emergency programme included two repeat L class destroyers, built by Beardmore (Lochinvar and Lassoo).

(DRAWING BY A D BAKER III)

Thornycroft’s Meteor had four boilers, two of them trunked into the fatter middle funnel. Her middle gun is just visible between Nos 2 and 3 funnels. The lines were an expanded version of those used for HMS Hardy and also for the Italian Indomito, a Thornycroft design built in Italy. The Italian ships were the first turbine destroyers built in that country. Thornycroft had previously designed the Italian Nembo class, built by Pattison, which were roughly equivalent to its thirty-knotters (the next Italian destroyers, the Bersagliere class, were a derivative built by Ansaldo). The Indomitos were the next built. As in British practice, they introduced a forecastle, and they had four boilers in two compartments, feeding three funnels. The Ardito, Audace, Pilo, Sirtori, La Masa and Cantore classes – a total of thirty ships in addition to the first six – were slightly larger improved versions; a further series of these 700-tonners was cancelled at the end of the First World War. The four follow-on Palestros (and four similar Curtatones ordered at the same time) were considered an enlarged and improved version of the basic Thornycroft design. Compared with contemporary British destroyers, the Indomitos were more heavily armed, with a single 4.7in gun and four 76mm/40 or with five 4in/35 guns plus a single pompom. The problem of placing guns on the centreline in way of the machinery not yet having been solved, they had their smaller guns on the beam in the waist and right aft (in echelon on the beam, to avoid fouling the propeller shafts). The Indomitos displaced 770 tons (metric) full loaded, 672 light, and were 73m × 7.32m × 2.66m (239.4ft × 24ft × 8.7ft). They were rated at thirty knots (16,000shp). The Pilo class had two 4in guns on the forecastle mounted abeam, as in HMS Swift, plus a second pair of torpedo tubes, all four being mounted on the sides of the ship (during the First World War, ships were fitted with British-type combined sweeps, and their quarterdecks had to be cleared, so two guns were eliminated and the other two placed abeam further forward; the four single tubes were replaced by two twins). Centreline guns aft were finally introduced in the La Masa class, which had one right aft and one between the after funnel and the after steering station. The main differences from British practice were the two guns abeam forward and the use of torpedo tubes en echelon rather than on the centreline, but these notes give some idea of the alternatives available to destroyer designers of this era. It is not clear to what extent Thornycroft was responsible for later Italian destroyers through its connection with the Pattison yard. This photograph of HMS Meteor was taken in 1914.

(NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM)

In 1913, with the Acastas and the specials under construction, it was decided to designate the 1911–12 ships as the K class. For a time it seemed that all would receive ‘K’ names to make it easier to associate them with that class letter. Although the names appeared briefly in Admiralty lists, they were not used. All ships were fitted with single sweeps while building.

In the aftermath of the 1911 design season, the DNC, presumably prompted by the Controller, asked his destroyer section to work out a less expensive design costing about £80,000, compared with the £90,000 or more of the new specials. He thought that might be possible on 800 tons, with two 4in guns and two torpedo tubes. Speed would be the same, twenty-nine knots. The least expensive Acorns averaged £82,500 and they had a pair of 12-pounders in addition to their two 4in guns. They could probably make twenty-nine knots. An Acorn without 12-pounders or KNC bulkhead would probably come in at the desired price. Repeat Acorns had been somewhat more expensive, but a stripped-down version might cost about £82,350.

This idea was soon dropped. In January 1912, the Controller asked for an improved Acasta with two twin (rather than single) torpedo tubes, but without reloads. Presumably this change reflected Admiral Callaghan’s increasing interest in torpedo fire in fleet actions (Callaghan wanted three single tubes, as in some German destroyers, but a Controller’s conference opted for the two twins). A suggested reduction in 4in guns was abandoned because German destroyers were being armed more heavily. Existing destroyers had 15-pounders (8.8cm, about 3.5in calibre) and it was believed (correctly) that newer destroyers would have 24-pounder (4.1in, 10.5cm) guns.

In March, the First Sea Lord approved a proposal to supply anti-aircraft machine guns (Maxims: 4500 rounds) to the 1st, 2nd, and 7th flotillas as they became available, other flotillas receiving them later. This applied to the new ships and to the Acastas.

The after searchlight would be controllable from the bridge. Length (between perpendiculars) was not to grow beyond the 260 feet of the Acastas, but the forecastle would be raised one foot, the ships given a raking bow and the flare carried further aft, and the forebody fined as far aft as the bridge (to avoid damage such as that suffered by the Acorn class). The Captain (D) of the 1st Flotilla (Acorns) complained that his ships were so lively they could not generally use their 4in guns. At first it seemed that some ships would have anti-roll tanks, but that was later reversed (a proposal to use anti-roll gyros, then being proposed for the US Navy, was rejected). Deeper (fifteen inches rather than nine inches) bilge keels were acceptable, but not double bilge keels; bilge keels caused drag and limited speed.

The sketch design showed four boilers, as in the Acastas (both three- and four-boiler arrangements were acceptable). Like the Fairfield and Denny specials of the previous programme, ships would have their middle 4in gun above the after boiler room, between the second and third funnels (a drawing of the three-boiler arrangement practically duplicated the arrangements in the Denny special). The gun was supported on a pillar passing through the middle of the after boiler room. This arrangement offered good separation between the after and middle guns. With the torpedo tubes blocking access to the middle gun from aft, its ammunition was stowed forward instead of aft. It was placed on a raised platform to allow access to the boiler room beneath it, but the platform could not be raised too high for ammunition to be passed up to it. The DNO also wanted to keep the line of sight below funnel smoke. The second and third funnels were raised four feet to keep smoke clear of the gun.

Adoption of the QF gun and twin torpedo tubes would add seven tons. Hull changes would add another six tons: higher bow, deeper bilge keels, and three inches more beam (to maintain stability). The 0.15-knot cost was entirely acceptable.

Twenty ships were planned (at a March meeting, the Controller decided not to buy any specials with different dimensions). The first sixteen ships were ordered on 29 March: four from Fairfield and two each from Denny, Parsons (hulls by Palmers), Swan Hunter, Thornycroft, White, and Yarrow. Fairfield offered the desirable improved Brown-Curtis turbine (which the E-in-C thought offered 2 per cent better economy than ordinary Parsons turbines at full power, and 13 per cent at low power). Parsons offered geared turbines, which gained an estimated 10 per cent in propulsive efficiency by running at higher speeds but running their propellers at lower speeds (280rpm compared with 1800rpm and 2000rpm at the turbines), the ship needing 22,500shp rather than 24,500shp. Compared with ordinary Parsons turbines, this arrangement was expected to gain 9 per cent at full power and 20 per cent at low power. White and Yarrow used three-boiler plants with two funnels. The others followed the boiler arrangement in HMS Shark of the previous programme, which had a forefunnel in addition to the other two. Two ships were later ordered from Beardmore, and two more from Yarrow. The Yarrow ships had been designed for anti-roll tanks, the space being used for extra fuel.

Matchless HMS Matchless exemplified the standard First World War Royal Navy destroyers built through 1916. She was ordered under the last prewar programme (1913–14). Matchless is shown as in February 1915. She had three rather than four boilers (Yarrow, 250psi), her middle 4in gun being mounted over the bulkhead separating the two-boiler forward room from the one-boiler after room. Two Impounder anti-aircraft pompoms were mounted alongside her bridge. Like the L class, these M class destroyers were conceived to carry four mines (note the mine tracks on the stern), but it seems they were never carried, and the mine tracks were eliminated in favour of various sweeps. In response to reports of fast new German destroyers, these ships were rated at thirty-four knots. However, they had the same power output as the nominally slower L class, the difference being in the displacement on trial. At full speed, her 25,000shp direct-drive turbines ran at 750rpm, compared to 360rpm for the single-reduction geared turbines (27,000shp) of the R class. Ships came out somewhat heavy: Matchless was designed to displace 1126.5 tons fully loaded, but displaced 1154 tons as completed. The ready-service ammunition boxes shown on the forecastle were inclined at about a forty-degree angle facing inboard. The ship was later fitted for sweeping. By January 1919, the forward searchlight had been removed, the after searchlight moved to a new platform between the after torpedo tubes and the mainmast, two depth charge throwers added abreast the breech end of the after tubes, and a 2-pounder anti-aircraft gun placed on the original searchlight platform, which was enlarged.

(DRAWING BY A D BAKER III)

The Repeat M class destroyer Orpheus is shown in 1919 with standard war modifications such as elimination of the bridge searchlight and addition of antiaircraft guns between her twin tubes. Note the retained bridge semaphores. In April 1918, the standard depth charge battery was four chutes, two throwers, and eight charges, but many ships carried more charges.

(NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM)

HMS Murray was one of the original M class, with a straight bow and without a platform for the amidships gun. Note her unusually short funnels in this 1920 photograph.

(NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM)

On 30 September 1913, the Admiralty assigned L names to these ships, which had been called the Rob Roy class. They became the first British destroyers whose names matched their class designation.17

In spring 1912, while the L class was being ordered, German destroyers were reportedly making much higher speeds. The new British destroyers might be obsolete before they were laid down. Although the Controller pointed out that in a seaway the British ships would be faster, on 19 June the First Lord, Winston Churchill, wrote the Controller and the First Sea Lord that ‘I cannot say how serious and urgent this question seems to be. We should get on without delay with the designs for the 13–14 TBD which may have to be started early [ie, to meet the new German ships]. Nothing less than thirty-six knots will be satisfactory.’ Yarrow had already offered higher speed for £3000 per knot.

The Controller still wanted destroyers strong enough and properly shaped to maintain fairly high speed in average sea conditions, without sacrificing too much strength and weight, hence he did not expect the highest conceivable speeds. Armament would match that of the 1912–13 ships (L class). The DNC expected to have the sheer drawings and midship section approved by the Board and building drawings roughly pencilled by September, with finished profile and plans ready for issue by mid-November. Since bids for the 1913–14 destroyers would normally have been invited no earlier than mid-1913, this would push the schedule ahead by more than six months.

The DNC estimated that the desired speed could be achieved on a length of 275 feet (between perpendiculars) and a beam of twenty-seven feet, with 33,000shp rather than the current 24,500shp (his first estimate was 300 feet length). Ships would carry 150 tons at the beginning of trials, compared to 250 tons in an Acasta. Given the need for higher speed, on 26 July, the DNC asked the test tank to run a model of a 736-ton destroyer at speeds up to forty knots, and also to try it 10 per cent light and 15 per cent heavy. The E-in-C estimated machinery space and weight for two-shaft four boiler 30,000shp and 33,000shp plants, using two boiler rooms with common firing spaces (ie, with boilers facing each other, the uptakes being at each end of the boiler room). A narrow beam would complicate machinery arrangement, so the E-in-C asked for another foot and a half.

There was no hope that the government would fund a large supplemental destroyer programme in advance of the usual 1913–14 Estimates. Thornycroft offered to build an Admiralty design on spec on the understanding that if the Admiralty bought destroyers in the coming year (a certainty) it would first buy theirs at a price fixed beforehand. The Controller pointed out that on this basis the Royal Navy could get perhaps six new destroyers well in advance of the usual 1913–14 orders. Churchill approved the idea on 17 July, the Controller deciding to order two ships from each of Thornycroft, Yarrow, and White. These designs would compete with the Admiralty design for the rest of the 1913–14 ships. As the whole idea was unofficial, the Controller would ask the firms to forward their designs to him personally for review. Later, White was replaced by Hawthorn Leslie. For a time, it seemed that the firms would all be asked to build to a standard new 275-foot Admiralty design, but that did not happen.

Radstock HMS Radstock, a war-built R class destroyer, shows typical wartime changes as newly completed (December 1916). The R class was essentially the M class with geared rather than direct-drive turbines, hence with two rather than three screws (they also had slightly more power, 27,000shp instead of 25,000shp). Unlike Matchless, she had shields on all three 4in guns, and she seems to have had a plated-in bridge front with glass windows. The entire bridge structure was reshaped, partly to reduce damage when it was swept by seas. The paravanes right aft, with two winches just abaft the after set of torpedo tubes, were probably for explosive sweeps (the high speed submarine sweep). There was a similar high speed mine sweep using inert paravanes (Type C instead of Type Q). A single depth charge with a hydraulic release is visible next to the starboard side lattice davit. Both davits could be raised to the vertical. The winches used to handle the paravanes are visible on both sides just abaft the after torpedo tubes. A single 2-pounder anti-aircraft gun was mounted on the former after searchlight platform between the torpedo tubes, HMS Skate was the sole unit of this class to survive into the Second World War; her later configuration is illustrated in the last chapter. Radstock was sold for scrap in 1927.

(DRAWING BY A D BAKER III)

The Thornycroft ‘special’ M class destroyer Patrician served postwar with the Royal Canadian Navy. The US Navy photographed her at San Diego on 2 December 1924.

HMS Truculent was a Yarrow R class ‘special’ with her two forward uptakes trunked together to carry them away from her bridge. Yarrow M ‘specials’ were similar. The earliest had vertical stems and flimsy bridges carried on an aftwards extension of the forecastle, the sides of which were open: these bridges could be further aft than in conventional Ms. In later ships, the sides of the forecastle were plated in. The ship is shown in 1919.

(NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM)

Greece bought the first export version of the M class; the Royal Navy took over all four ships in 1914. Dimensions matched those of the M class, but the double boiler room was adjacent to the engine room, a change the Royal Navy would later make in the Modified R and S classes. In this case the builders took no advantage of the change to bring the bridge aft. The contemporary DNC view would have been that such rearrangement endangered the ship because an underwater hit on the bulkhead between the double boiler room and the large engine room might have caused her to founder. Because of this rearrangement, the support for the middle 4in gun had to go through No 2 boiler room, between Nos 2 and 3 funnels. As completed, the two ships built by John Brown (Medea and Medusa) had raised funnels, the others following suit in wartime (these were the only M or R class destroyers with raised forefunnels). Melampus is shown in 1919.

(NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM)

On 14 August, when the legend of the DNC’s design was completed, the DNC met with the Controller and others.18 Yarrow’s Firedrake, the special 1911–12 destroyer, had not yet been completed, but the Controller apparently asked whether she could make the required speed if lightly loaded. That was ruled out, but some juggling suggested that a slightly redesigned Firedrake operating on a different basis for trials (enough oil for six hours) could make thirty-four knots.19 Nothing radical was needed; the DNC would simply apply much the same standards to British design that the Germans were applying to their own destroyers, loading them lightly to make impressive speeds. He switched from the 275-footer to a 265-footer, which would make thirty-four knots on 25,000shp on trials.20 A legend and sketch design were completed in September 1912. Work on this design continued through March 1913, in preparation for the usual orders for the 1913–14 Programme. In November 1912, it was modified to carry four mines on the upper deck, to provide for fuelling at sea, and to move an enlarged generator from the usual separate compartment into the engine room (where space became available because the number of turbines was reduced). More generator power was needed because the after searchlight was to be enlarged from the previous 30–34 inches. A May 1913 legend omitted the mines but included two 1-pounder pompoms on high-angle mountings replacing the earlier 0.303in Maxim machine guns. By this time machinery weight had grown slightly, and trial displacement was given as 908 tons.

A new Barr & Stroud rangefinder would enable a destroyer to take ranges in almost any weather. Should destroyers have spotting platforms and other means of fire control comparable to those on board larger ships? The Royal Navy settled on voice tubing, one main tube having branches to bridge, torpedo tubes, and searchlights and another from bridge to middle and after guns. A smaller-diameter flexible pipe would connect the bridge to the forecastle gun. The alternative sound-powered telephones (telaupads) were rejected as unreliable after trial in HMS Beagle.

Meanwhile the three firms were sent draft requirements based on the 275-footer. The ship should make thirty-five knots on an eight-hour full power trial, with 150 tons of oil on board (full capacity 200 tons in war tanks, maximum possible in peace tanks). Armament and accommodation were to be as in the 1912–13 ships (L class). The firms were not enthusiastic to leave the price open, and it took the Admiralty until August 1912 to work out arrangements. None of the firms needed the full length that the DNC thought he needed. Thornycroft and Hawthorn Leslie submitted designs for 265-footers, and Yarrow produced a ship 260ft 3in in length. Outputs were not too far from those of the Admiralty design: 26,500shp for Thornycroft, 27,000shp for Hawthorn Leslie, and 23,000shp for Yarrow. All of the ‘specials’ had twin screws. The Yarrow ‘specials’ had three boilers, their Nos 1 and 2 uptakes trunked together to form a funnel well separated from the bridge. The Thornycroft ‘specials’ had four boilers, Nos 2 and 3 uptakes being trunked together to form a single funnel. The Hawthorn Leslie ‘specials’ had four boilers and four funnels.

During the First World War, Vickers and John Brown sold a modified M class design to Spain, the main change being an additional boiler. The Admiralty protested that the two builders were exporting valuable shipbuilding knowledge, but the sale went through anyway. The Spanish ships were not laid down until after the war (the first was in 1920). Alsedo is shown. Note her bridge rangefinder, a most unusual feature for destroyers of this size. It was probably associated with Vickers’ destroyer fire control system, a version of which the Royal Navy adopted.

A Thornycroft M or R ‘special’ photographed near Queenstown in 1917–18 shows the typical end of war configuration of British destroyers, with a prominent paravane mounted aft. Paravanes were used both for minesweeping and (in explosive form) for ASW. The ship’s identity is unknown, because none of the Thornycroft ‘specials’ seems to have had a pendant number ending in ‘68’. In contrast to the Grand Fleet, the ASW force in the Irish Sea seems not to have painted on the flag superior in its pendant numbers.

(US NAVAL HISTORICAL CENTER, DONATED BY LOUIS S DAVIDSON)

Plans apparently called for fifteen destroyers, that is, nine Admiralty ships.21 Options on the on-spec destroyers were exercised about March 1913, Yarrow offering a third ship (which was bought in May). The Controller then wrote that he wanted to spread the remaining ships as widely as possible: two from John Brown (with Brown-Curtis turbines), two from Palmers (Parsons), two from Swan Hunter (Wallsend Machinery), one from Denny (Parsons), and one from White (Parsons). The First Lord cut the programme to six ships (Denny was omitted), the remaining three being replaced by prototype leaders (see below).

In contrast to previous practice, each of the three boilers in the Admiralty design fed its own uptake, Nos 2 and 3 being slightly further apart than Nos 1 and 2. The amidships gun was supported by the bulkhead between the two boiler rooms, the uptake for the one boiler in No 2 room being led abaft it (the funnel was shaped to provide the necessary clearance). Admiralty ships all had three shafts, the E-in-C having rejected two-shaft arrangements. The key change from 1912–13 was that the trial load was based on a six-hour rather than an eight-hour trial, so it took only 500shp and five feet more length to transform the twenty-nine-knot L into a thirty-four-knot 1913–14 destroyer. The design showed a new flat (underbody) stern rather than the earlier cruiser stern, for which the DNC claimed a considerable improvement in speed and manoeuvrability, without slamming in bad weather. Generous flare forward made these ships better sea-boats. Building drawings were submitted on 8 September 1913. The 1913–14 destroyers became the first of the Admiralty M class and the prototypes for ninety ships, most of them built under the war programmes.

Greece ordered four destroyers in 1913, sometimes described as essentially copies of the M class, from John Brown and Fairfield. Unlike the M class, these had the double boiler room adjacent to the engine room, carrying the middle guns between Nos 1 and 2 funnels rather than between Nos 2 and 3 funnels. In addition, the forefunnels were raised. They were still under construction when war broke out in August 1914, and were taken over by the Royal Navy as the Medea class.

In April 1915, John Brown and Vickers jointly offered an M class destroyer with a fourth boiler (hence four funnels) to Spain, whose shipbuilding industry Vickers then dominated. The DNC protested unsuccessfully that in doing so they were providing the current British destroyer design to a foreign power. The resulting Spanish Alsedo class was built under the Navy Law of 17 February 1915, and the first ship was laid down in 1920.