A story

Entering the classroom John chose a place not too far forward, not too far back, and tipping, shoving, scraping, adjusted his chair to accommodate his body in a position of maximally receptive inertia. The others, as they arrived, busied themselves with their chairs as John had, then fell to cursory chat about the ordeal of study. They flicked in their folders for a clean page and doodled, stilling their thoughts. John drew a spiral around the punchhole in his page. They were not to be condemned. He had a theory: no matter how active their life elsewhere, they wiped themselves blank when they entered the teaching environment. Automatic primal therapy. They were ready for knowledge, in a dry fashion, yawning, shuffling, awaiting the lecturer, who was late. John, on principle, was passive too, because he was dedicated to openness and, anyway, he didn’t stop at passivity. Beneath that layer he seethed with inventiveness, energy and decision. Did the others realise? He wondered if it was the case with them too. They eyed each other indifferently, looking content and compact – except for the old Christian Italian lady, who gave watery smiles to the air. They were dried fruit hoping to be dunked and reconstituted in the syrupy sweetness of truth.

The lecturer was a solid chap whose commitment to the subject had led him to acquire a Chinese sense of humour. He joked as he unpacked his bag, and the class stirred familiarly to reassure him. How to tell the time in Chinese. Like everything else in the language, it was sagely and wonderfully at odds with the way things were done in English.

The lecturer was giving the first example when the woman walked in. He stopped in his tracks to usher her to a seat. John had never seen her before: she certainly hadn’t been there in the first semester. She sat on her chair, book and paper in her lap, and leaned forward at the lecturer, smiling keenly. With her hand under her chin, smiling, she welcomed the foreign sounds and the information. Her eyes were bright blue coals.

Behind her back the others in the class turned and made querying faces. Some frowned and were affronted. She couldn’t just walk in like that after half a year and upset the group dynamic. Others pulled themselves up, or slouched back coolly, to intrigue and allure her. She didn’t notice the rest of the class. Indeed, John saw, her attentiveness kept giving way to a tired dazzle.

She didn’t sit back until the end of the lecture, when she turned to her neighbour and said, ‘Isn’t it fabulous! I’d forgotten!’ She laughed, bubbling. ‘But it’s insanely difficult. I’m never going to catch up.’ She flicked her fine, dust-coloured hair out of her eyes. Turning to the people on her other side, she looked, for a moment, terribly worried. ‘What am I going to do? You’re all so good.’ Then she gave her rising tickle of a laugh again.

Her neighbour was Kevin Spike, the hawk-eye of the class. He stood up, buttoning his maroon blazer, and waited by the woman’s seat, encouraging her to rise and leave under his escort. ‘How come you’re just picking it up now?’ he asked.

She gathered up her things, still smiling, and, with half a turn of goodbye to the others, walked quickly ahead of Kevin out of the class. ‘Well, you see, it was hopeless. I first – ’

She was gone round the corner of the door before John could catch her story. There was only the string of images trailing behind her down the corridor, flashing through John’s head, twenty-four per second.

The evidence was considerable. On a normal day John spent his time working methodically in his room. Now he was drinking coffee in the Union, looking up from the cup whenever a fair-haired woman of medium height appeared, whenever a brisk lively movement occurred on the edges of his vision. Where had she come from? Perhaps she had a connection with the lecturer and was given special treatment. In his mind John saw her park her hair behind her ears – where it should have stayed, except it fell forward and made her look mysterious and late-night. John couldn’t wait for the next lecture. He had theories for everything, and speculated that this might be love.

He took the seat next to the one she had occupied, peeled off his parka and laid it across her seat. If his behaviour was obsessive, well, then, the others in the class were his rivals and would be equally devious. From the stairwell a clicking of heels announced her, rushing ahead of herself. John retrieved his parka only a fraction before she appeared in the doorway. She beamed, took the hint and collapsed in the empty chair. ‘Hi!’

John responded as softly, as significantly, as he dared.

‘What’s the time?’ she said. ‘I thought I was ages late. God I’m disorganised. It was bumper to bumper all along Belconnen Way and I just couldn’t move. My watch must be wrong. Anyway thank goodness I got here. It’s absolutely pouring outside.’

She shook her hair and one of the raindrops fell on John’s hand. As she settled herself he drew the hand back. Ceremoniously, with the tip of his tongue, he licked up the drop. She unwrapped her scarf and took off her coat: her chequered vyella smock underneath looked so warm John wanted to touch it. She gave a determined heave to slow her breathing. When her breasts rose they sent out a soft wave, as if she were throwing something off, stripping herself back to a kid who was ready to learn. But nothing was happening in the classroom, and she bent over to John, whispering that she’d love a cigarette. As she came near, he could do nothing but point, silently, at the No Smoking sign.

After a pause Kevin Spike leaned forward, offering a gold packet. ‘Cigarette, Ginny?’

‘Oh no, I don’t think I will now, thanks.’

So that was her name.

When the lecture started she turned to John again, mouthing, ‘I’ve forgotten my book?’ He looked at her humorously and pushed his own book so far in her direction that it tipped off the table attached to the armrest. It spread-eagled on the floor, and he had to crouch to pick it up. At the end of the lecture John said, so flatly it was neither question nor statement, so warily it showed total disinterest, ‘Off home now.’

‘Well – ’ she grinned, shrugging, ‘via the bar.’

Kevin Spike pushed forward and asked if she was still coming.

‘Are we coming?’ she asked generally. ‘We,’ with John at her side. But she was walking towards the door in front of Kevin.

‘I wouldn’t mind a drink,’ declared John.

He would mind it; he would hate it; but he would hear more of her magical chitchat.

He discovered that she was doing Chinese as part of a DipEd and had deferred the whole thing after six months to go travelling in Asia with a really wonderful friend. Now she was back to finish off the second part of the year. The last syllable of her sentences rose with unanswered possibility. After the first drink a good-looking man in his middle twenties came and took her away. He was got up, in punk style, like a battered schoolboy. Was he the friend? As quickly as possible after she’d gone – there was nothing to be said or done to Kevin Spike – John took himself off. He saw them then, in the distance, Ginny and the man, gliding behind the sheet-glass wall of Life Sciences, short-cutting to the carpark.

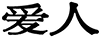

They learned many essential things in Chinese. They learned that in the opinion of some linguists there is no passive voice in Chinese. There is only greater and lesser activeness. There is no chance of withdrawing irresponsibly into a state of being worked on. On the other hand there is the compensation that our habitual passive can be strangely transmuted through Chinese eyes into an active living force. For example the character  , pronounced ‘ài’ or ‘eye’, meaning ‘to love’. Typically it combined with other basic words to make binary compounds: you could take

, pronounced ‘ài’ or ‘eye’, meaning ‘to love’. Typically it combined with other basic words to make binary compounds: you could take  , pronounced ‘rén’, meaning ‘person’, and put it with ‘ài’ to make

, pronounced ‘rén’, meaning ‘person’, and put it with ‘ài’ to make  : àirén. Literally it means ‘love person’. In English it must be translated as either ‘lover’ or ‘beloved’. There is nothing in between. In the People’s Republic it must be translated as ‘non-sexist spouse’, in Singapore as ‘mistress’. But ‘love person’, the actively loving or the passively loved, John reckoned that in Chinese there could be no distinction. Simply by loving you would necessarily be loved back.

: àirén. Literally it means ‘love person’. In English it must be translated as either ‘lover’ or ‘beloved’. There is nothing in between. In the People’s Republic it must be translated as ‘non-sexist spouse’, in Singapore as ‘mistress’. But ‘love person’, the actively loving or the passively loved, John reckoned that in Chinese there could be no distinction. Simply by loving you would necessarily be loved back.

John was sitting behind Ginny, the day they learned about love persons. He looked at the back of her head and willed love over her in waves. It was an experiment and, if the theory were correct, she would become aware of him, start to fidget and, finally, turn for a quick smiling glance at him. But she didn’t, and on the way out he couldn’t look her in the face.

The class dispersed in various directions. John went by himself down the several flights of ill-lit stairs leading to the back concourse. Outside, his eyes were dazzled by the low sunset, fiercely orange behind the black mountains that threw light to the ends of the sky in stupendous spears. Bewitched, he pressed on, lost in it, until suddenly, crossing the concourse, he all but collided with Ginny.

‘Hi,’ she said and stopped. She was wearing sunglasses.

‘Is it the same colour to you,’ asked John, ‘through those things?’

She smiled but didn’t take the glasses off. ‘It’s better.’

They looked across ten miles of suburban development at the orange fusion. Four students with squash racquets came out of one door, walked along the building, and entered another door. ‘There aren’t many people round,’ said Ginny.

‘There never are,’ said John, ‘not real people. It’s illusion. That’s my theory.’ His legs were apart and he had the weight on both feet, confronting her.

‘That’s what they say about you,’ was her reply.

‘They?’

She laughed and made her eyes bulge. ‘A thousand million Chinese! Can you believe they actually communicate in that language? Anyway, see you.’ And she pursued her geometric path towards an exit from the concourse rectangle.

John lived in a room in a hall-of-residence. By his bed, in a pot, there was a comfrey plant, an ancient medicinal herb that died in winter and came alive again in spring. But John, although he watered it carefully, had little faith that anything would grow out of the remains of last year. He looked at the old leaves, shrunk and crinkled like grey potato chips, and wondered if the comfrey were technically alive or dead. A book called The Secret Life of Plants had talked of the incredible sensitivity of all organic forms – to emotions, events, hopes, stimuli of every kind. So John stood in front of the pot and repeated his experiment from Chinese, emitting waves of love at it. When nothing happened he was consoled. If a mere plant didn’t respond, why should he ever have thought a human would? Such ideas were superstitious snow!

That night, in the remotest passage of his sleep, he felt something tug him up from the deep. He kept his eyes shut, wanting to stick with his dreams, whatever they were. But slowly, sluggishly, he rolled over and edged across to hug the body in the space beside him. He reached out his arms to encompass the warm loved shape, but the sheets were cold in that part of the bed. He woke properly then and opened his eyes on the claustrophobic pitch of his room. A sorrow filled him, strong as fear. He found his body balancing along the rim of his single bed, making a place for the one he had loved in the night. But no one was there.

After the next Chinese class John intercepted Ginny in the corridor. ‘Do you feel like getting together to practise for the oral?’

‘Yes,’ she said immediately. ‘Yes, great,’ nodding, ‘come round to my place?’

‘When?’

‘Tonight.’

He nodded cautiously. ‘Okay.’

Ginny lived in a group house: two females and two males. Marilyn suffered from anorexia nervosa and worked a computer in the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Ted and Todd studied Natural Resources. It was a townhouse in the far new suburb of Holt. The group was eating vegetable casserole and rice around the television when John arrived; Marilyn and Ted in their running shorts, Todd in battle trousers and a T-shirt.

‘Will you have a drink?’ Todd challenged, ‘A beer?’

‘Ah, no – thanks.’ John stood there.

Ginny began to talk rapidly. ‘Did you get here all right? It’s incredibly difficult the first time. You’ve probably been driving round in circles for ages. Have you?’

‘I rode my bike.’

Ted looked up with interest. ‘Great,’ he judged.

Ginny heaped a forkful into her mouth and, chewing, rushed with the plate to the kitchen. ‘That was delightful,’ she said, swallowing. ‘Now John – ’

While she was in the kitchen she continued calling to him. He stayed awkwardly in the living room, looking at the others who were looking at the television. When she returned she was in command, smiling and carrying a teapot and two small Chinese cups on a tray. ‘We can practise better in my room,’ she said for the benefit of the others. ‘It’s quieter there.’

Though it was not yet spring, her window was wide open and the room was fresh. There was a line of books in the room, a line of plants, a line of non-commercial lotions and a mushroom ring of jars, vases and boxes on a little chest. On the wall was a green Asian cloth, otherwise the room was white.

Ginny closed the curtains and lit two candles. They sat on the floor with the teapot between them. Ginny talked in excited bursts, then fell soulfully silent for a stretch. John spoke in single, laconic, equally spaced sentences. Whenever they ventured into Chinese they giggled, and sipped some more Chinese tea. They were still on the floor at two in the morning. John was propped against the bed and Ginny had smoked endless cigarettes.

‘I better be going,’ he said at last.

‘You don’t have to,’ she said.

He put his hand on hers and she welcomed it with her fingers.

He was silent, then shuffled near and kissed her.

When they were in bed, when he was lying against her skinny, beautiful, fragrant form, when with her hands she seemed to treasure him, when she whispered ‘John’, he couldn’t stop wondering why he had been chosen.

On the ride home, seven kilometres, tingling, he sang his tremendous luck. His luck that he knew was his love.

But was it love? He could afford to step back now. He noticed that the comfrey plant by his bed had put out two tiny spiky shoots. He regarded them with approval, and paused a moment to emit his remaining energy in their direction.

In the morning, when he awoke, he was refreshed and the shoots had doubled in size. There were four of them now, and the sun was shining. From his high vantage point in the residence he could look out and see mountains. In the morning light they were violet and airy, as if they belonged somewhere else, and they made John feel different.

That day he began to feel differently about many things. He saw a maintenance man sitting on a stone under a willow by the artificial pond in the college courtyard. For a moment the man was an elder in a scroll painting. On the approach to the residence block there were black plum and cherry trees studded with pale buds. They became Zen foreground. They had their mode of being as John had his, yet something linked them to him. Even the other students shambling about in the Union could be seen as fellows on the path, on the Way. But was this love?

He came early to the Chinese lecture and sat on the chair beside the one where Ginny would sit. He opened his folder and scribbled like the others, but now the idleness and inconsequence had vanished and the occasion acquired fantastic meaningfulness. Just before time, Ginny dashed in and whispered that she wanted to speak to John outside.

‘How are you?’ she said, pressing her back against the wall of the corridor.

He looked at her blankly.

‘Listen, I can’t stay for this lecture. I’ve got to see a friend.’

His tongue was a tangle of inexpressibles. He might as well have tried to speak in Chinese.

She was saying, ‘What happened – last night – it was just something I wanted to happen.’

He gave nothing away. ‘I wanted it too.’

‘I know. That’s all.’

‘That’s okay,’ he confirmed.

‘Anyway, look, we must see each other soon,’ she said, smiling at him, turning from him, spattering down the stairs.

John spent most of the twenty-four hours until the next Chinese class in the Union drinking coffee. His favourite theory of all was that the individual should exert no pressure on the world. The being should be as if non-being. The world should do all the determining, all the moulding, all the pushing and shoving. He sat at one of the plastic tables overlooking his cup, moving only when the lady came to wipe the table. He waited until he was actually late for the lecture so he could make an entrance. But Ginny wasn’t there. During the hour Kevin Spike tapped his shoulder and passed him a message on a piece of Defence Department notepaper. Kevin had written: ‘I saw Ginny on the way here. She wanted me to tell you she’s feeling crook and will catch up with you later.’

John’s room in the hall-of-residence was small, but that night it seemed so enormous and empty he couldn’t stand it. And there was the whole weekend to go.

At midday on Saturday , after he had busied himself all morning, he rode his bike out to Holt. It was the first sunny day of the season. Marilyn and one of the Natural Resourcers were playing frisbee on the nature strip. ‘Hi!’ they yelled, bouncing, offering nothing more. John went up to the front door and knocked. Todd, the other Natural Resourcer, answered. He was in his dressing-gown. He allowed John to walk into the living room, where the curtains were still closed. In the gloom, above the music, John heard Todd say that they hadn’t seen Ginny for a few days.

‘She could be at her parents.’

John had not imagined she would have parents.

‘Wait if you want to,’ said Todd.

But John wanted to return to the hall-of-residence. On the ride back an insect got in his eye and he cried. Why wasn’t it working?

That Monday he was walking up the steps to the top concourse of the College of Advanced Education. It was early dusk and the view towards the sun was a fairytale. John couldn’t help being enchanted. It was so clear and gentle. The mountains were blue-violet wash. The sun was silver. On the horizon a single green cloud rose in a zigzag, like a cartoonist’s squiggle. All the way down the valley the planned development looked like scattered futurist cubes and carefree twinkling lights. John ascended the stairs as if advancing towards an unveiled dream city. The concourse was a high concrete plateau. It might have been an open-air stage for the mountains, or a slab from which the suburbs could witness sacrifices. At that moment it was depopulated, save for one couple. They were alone among the select native shrubbery. John saw the man put his arm around the woman. The woman stood up on tiptoes to kiss him quickly on the cheek, leaning into him, then lowered herself, pulled her sunglasses down, and was gone. The man walked on as if he were going somewhere. The woman was Ginny. John looked at the revealed city. It was a death metropolis fuelled by human dreams.

John and Ginny sat next to each other in the lecture. She greeted him solemnly. He felt the sharpness. They had a further lesson on binary compounds and the lecturer, beaming at the mysteries he imparted, introduced the word

bó ài – and its derivation. ‘You know the word bó meaning “broad” or “wide”, as in broadcast, sowing the seed wide. You know ài meaning “love”. Put them together and you have “wide-love”. What is this concept?’

bó ài – and its derivation. ‘You know the word bó meaning “broad” or “wide”, as in broadcast, sowing the seed wide. You know ài meaning “love”. Put them together and you have “wide-love”. What is this concept?’

‘Promiscuity,’ snorted Kevin Spike in a stage whisper. Beside John Ginny giggled.

‘For the Chinese,’ the lecturer continued, oblivious, ‘bó ài means “universal brotherhood”.’ He paused so the class could contemplate the celestial simplicity.

Wide-love, thought John. He could almost accept the concept, quietly and soothingly, almost. He turned to Ginny, whose eyes met his with an expression of indecipherable wonder. He had a theory. All right, he understood. It was wide-love that she practised. It was her version of universal brotherhood and was only proper. He had no special claim.

Afterwards John and Ginny went to the Union together, to speak in Chinese over their coffee as training for the oral. Suddenly the sensation of being with her came back, trying to assert itself. She held the coffee cup daintily in her hand, not quite keeping it level. It was surely that hand he had touched. But the more her sharp eyes shone at him, the less he knew whether it had happened or not. It was imperative not to be deceived by the illusion of an action. Everything reduced to passivity in the end. Everything reduced to receptivity. Everything reduced to dream. His own love was only one drop in the universal sea.

Ginny suggested they should arrange a time for further oral practice.

‘It can wait,’ said John gallantly. He didn’t want to push her into something that wasn’t real. ‘Are you free on the weekend?’

She at once gave a great long uncontrolled speech about all the things she had to do, her assignments, her parents, her house, her hydroponics, her really wonderful friend, concluding that Saturday was fine.

John nodded. She brushed back her hair and laughed wildly.

‘Great,’ she said. ‘See you.’

His theory was that it had never really happened. That seemed the right approach. In the evening he put himself in front of his books. The comfrey plant had exerted itself, and four large green leaves now sprouted from the pot. They were ridiculous. He laughed, to distract himself. He would see her next Saturday and they would talk in Chinese. He had behaved well. He had done nothing possessive towards her. He had done nothing at all. He shifted restlessly and turned the first of many pages.

Hours later there was a knock. The midnight intrusion startled him. He had been deep in study. Anxiously he went to the door. It was Ginny, face rosy, puffing. She’d been in the bar.

‘Sorry,’ she said clumsily. ‘I’m sorry. Are you asleep?’ Something had changed her since the afternoon.

She walked in and sat down heavily on the bed, bowing her head guiltily. John was at a loss.

‘At least I got the right room,’ she said. ‘Sorry to bother you. I couldn’t wait – ’

John stood away from her, wanting to go to her but not doing so. ‘Is anything wrong?’

She kept her eyes to the floor, shaking and altering position in great uncomfortable heaves. He couldn’t stop thinking, nervously, about what was happening, watching for signs, wondering. The comfrey leaves had pricked up: the charge in the air would do them good. He prayed that she would speak – explain what was going on and release him from uncertainty.

‘What?’ he said, thinking she’d made a sound.

The room was monstrously vacant. Sunken on the bedspread, crouching round her knees, Ginny looked like an unwrapped parcel. John was hot, and heard thumping in the cave of his chest.

He went to her and put his hand on her head. At the same instant she spoke. ‘What are you doing? Why don’t you say anything ever? Why don’t you do anything? What’s going on?’ She had been talking to the ground but now faced him. ‘I’m sorry. I can’t help it. I haven’t done anything wrong. I don’t want to hassle you but – oh God! – ’ She put her head down against his knee.

She had done it. He gasped, half-yelping, half-mumbling. ‘But I love you!’

In a convulsive motion, strong as shock, he jerked towards her.

‘John?’

He had tears in his eyes.

They were together. It was real. Squeezing each other they understood that they filled the curiously matter-of-fact hall-of-residence room.

In the morning they opened the window – the world. They faced the furthest mountain, which was tipped with snow, and the nearer ones, glowing purple. Nearer still the suburbs were busy, packed with green. It was spring and the cherries and plums made pink and white spray. All was in proportion: background, middle and fore. John gulped the air. They touched each other, and, as each traced a separate path over the other’s body, their hands at last met and compounded.

They called the scene outside On a Road to the Yunnan Mountains, or, Approaching the Capital of the Southern Province. Overnight, overstimulated, the comfrey plant had produced two bellflowers which now tinkled in the morning breeze. There was no theory to cover it. Love person, love person, blew John in Ginny’s ear. Together they looked out at the sprawling houses, all similar, containing rooms containing people, as blank and deceptive as Chinese boxes. Wide love could know them all.

1980