Chapter 15

Ottawa, Ontario

National Gallery of Canada

The best way to reach the crystal-towered gallery overlooking the Ottawa River is by walking through the entrance on Sussex Drive, next to the Chateâu Laurier Hotel. You descend to the Rideau locks, walk along the Rideau Canal alongside the hotel, down to the river with the Canadian Museum of History beyond, a view of colour, architecture, and the sweeping Ottawa River. Then you ascend up to the side of Moise Safdie’s elegant museum. You enter, passing by Maman , the giant egg-carrying spider (thirty-feet high and thirty-three feet wide) meant to be a nurturing and protective symbol of fertility, motherhood, and shelter. Odd, it looks huge and spooky, but a great introduction to a gallery. The sculpture is by Louise Bourgeois, a French artist.

You enter and ascend by a long runway to a cupola, a feeling of Spain. Beyond, a view of the Parliament Buildings and Supreme Court of Canada.

Saint Mark’s and the Clock Tower, Venice (c. 1735–37)

Giovanni Canaletto (1697–1768)

A big, big surprise. You assume it will be a run-of-the-mill Giovanni Canaletto, but …

This is a perfect picture for an iPad photograph. I took nineteen myself: the picture itself and the details. Enlarged, the details are the thing! He has painted a square of life, living, gossip, commerce, laundry, potted flowers, pastelled mosaics, chimney pots (eleven?), a defecating dog, turbaned tents, and the subtlest, mottled grey walls possible.

Canaletto was a great favourite in England. He churned out countless pieces, many of which were symmetrical and precise, lacking personality, but always great line and architecture. This has personality.

JP

(Image not available.)

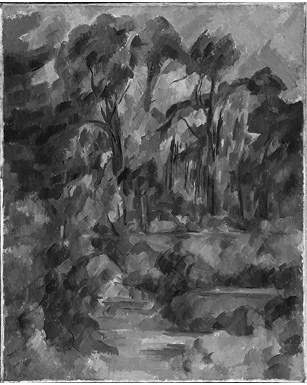

Forest (c. 1902–04)

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

Paul Cézanne, Forest, c. 1902–04

Oil on canvas, 81.9 x 66 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Photo: NGC

Room C215 has three giants: Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Klimt.

This is a marvelous, subtle Cézanne. In the MoMA, there is another view of the Château Noir, which has more strident colours. But here, subtlety is the leitmotif. Grey, pale olive green, ochre, Copenhagen blue, lilac, lavender, taupe, all patched with a dab of the brush, wet on wet. Yet the colours are no longer distinct. Slowly the dabs build up the architecture of the painting. Pissarro taught Cézanne to lighten his palette. He learned to experiment with close tones of grey and pale colours.

He wrote Pissarro, “You are perfectly right, to talk about grey; it alone reigns in nature but it is devilishly hard to capture.”

Look up close. Such delicacy? These gentle patches of colour, how he combines and alternates the patches. It is as light as Brahms glowing with the joy of colour.

Can these colours really be all there?

Cézanne is a happy struggle as words fail. It requires you to stand back, settle down, and enjoy a tapestry of patched colour.

JP

137. The Governess (1739)

Jean-Siméon Chardin (1699–1779)

Jean-Siméon Chardin, The Governess, 1739

Oil on canvas, 46.7 x 37.5 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Photo: NGC

Why do people go all goo-goo over Chardin? All he does is paint the ordinary, the everyday, the downstairs of households. Why this extraordinary praise for a mirror of the humdrum, the dark of the kitchen, the heat of the laundry room, the homeliness of the sitting room?

Chardin, born in 1699, lived for eighty years, a loner, no school, no followers.

Louis XV granted him a studio and living quarters in the Louvre. He rarely left Paris. His son, a history painter, took his own life at forty-one.

He rejected the styles of the time — Jacques David’s all serious emphasis on history, intellectual moral lessons. He rejected Boucher and Fragonard’s fluff, its frothy romance.

Feel the atmosphere.

Hard to describe “atmosphere,” no less paint it. But look at the space between the two heads, the child averting a gaze, the maid thinking, “Come on, little one.” That’s atmosphere!

Gombrich says:

He resembles Vermeer in the way in which he feels and preserved the poetry of a domestic scene without looking for striking effects or pointed allusions. Even his colour is calm and restrained and, by comparison with the scintillating paintings of Watteau, his works may seem to lack brilliance.

But if we are to study them in the original, we soon discover in them an unobtrusive mastery in the subtle gradation of tones and the seemingly artless arrangements of the scene that makes him one of the most lovable painters of the eighteenth century.1

“Lovable.” Quite a word. There’s no doubt when you inch up before a Chardin and examine his grainy technique, his thick paint, you are captivated, a mood of childhood memories, a chuckle at the reaction of a stubborn child resisting teaching.

The governess, a child about to leave for school, perhaps for the first time; on the floor, toys of the past, the open door to the future, the governess listening, almost willing the child, the boy on the cusp of shyness and trepidation. A moment. The ineloquence of youth.

This painting was an instant success in the Paris Salon of 1738.

He wasn’t brilliant in the sense of Vermeer, but his buttery touch evokes affection. A sort of, “Oh, oh, why look at that, look at the blue on the governess’s sleeve, the swallow sweep of the boy’s jacket, the black, black of his hat, and the boy’s moment of careful reticence.”

JP

138. Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Grounds (1820)

John Constable (1776–1837)

John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Grounds, 1820

Oil on canvas, 74.3 x 92.4 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Photo: NGC

Look at this delight. In the foreground: trees, with green, black-green paint, stabbed on with a palette knife — you can hear it scraping. A sun-dappled path, cows a creamy chocolate blur in a stream, with “Constable snow” skittering on the water.

Behind, the striking contrast of delicate wedding cake Gothic architecture, fragile, lacy, a vision of heaven, a roil of clouds breaking up in shards of paint.

Think Cézanne: with his subtle trees he did patches of bark not far off this, but eighty-two years later.

Constable captured an English vision of England — religion, tranquility, durability to dominate nature. Ahh, if it were only true.

There are other Constables in America, especially in the Frick, but this has power and lightness.

Constable did a more finished work of this view in 1823, which hangs in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. But it is more definite, without the elements of a sketch, primitive trees, or dreamy architecture. It lacks the cinema mood of the Ottawa painting. The trees become just trees, the church very real and dominant and the cows plump and clear.

JP

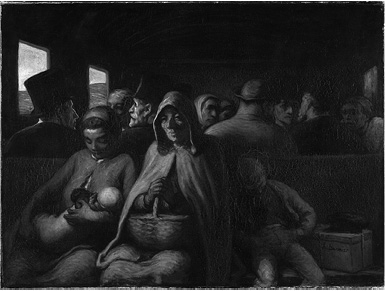

The Third Class Carriage (c. 1863–65)

Honoré Daumier (1808–79)

Honoré Daumier, The Third Class Carriage, c. 1863–65

Oil on canvas, 65.4 x 90.2 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Photo: NGC

Daumier, a master of portraying the venal, the lawyers of France, the legislators, his brush a social scalpel. He produced four thousand engravings and lithographs, many with the tone of what the French called enragé . King Louis Phillipe (1830–48) threw him in jail for six months. Daumier’s cartoons, every bit as savage as Goya’s, portrayed the king, a mountainous blob of a man, being fed by a conveyor belt of goodies. When censorship and jail curtailed Daumier’s political work, he turned to portraying scenes of ordinary life.

Here, a sketchy form that captures the fragility of existence yet conveys a bleak pervasive mood. The woman and child, isolated by poverty and the old lady’s inner thoughts, surrounded by “top hats” who will ignore her pain with a chilling certainty and utter indifference.

Sometimes the sketchy portrayal best captures the roughness of mere existence.

This painting is one you can never shove from your mind.

JP

139. Gibbous Moon (1980)

Paterson Ewen (1925–2002)

Paterson Ewen, Gibbous Moon, 1980

Acrylic on gouged plywood, 228.6 x 243.8 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Photo: NGC

There are times in viewing art when a piece or show is overwhelming, cutting one’s perceptions into ribbons and changing one’s aesthetic landscape. For me, this came with my discovery of Paterson Ewen’s Phenomena . But it wasn’t just the images, it was Ewen’s discovery of his “tool,” the router, that forged his brilliance and my appreciation of it. This was the perfect fit, Ewen’s router in Ewen’s hand.

At school in Montreal, Ewen was taught by Arthur Lismer and Goodridge Roberts, but in the early 1970s, he profoundly changed his métier , shifting from canvas to wood. He began by cutting large sheets of plywood, initially to make a large woodblock print, but once he was almost finished, he painted over the gouged-out wood. Gibbous Moon is an example of this new direction, bridging the gap between painting and sculpture, between reflecting images and creating them. As found in many of his works, he searched for inspiration in scientific phenomena, diagrams, old photographs from science or navigational books or encyclopedias, sources from which he had been drawing motivation since his childhood.

Ewen broke barriers in the art world by incorporating his science background into his luminous creations. His work moves me beyond reason, it speaks to something primitive yet reassuring. In a word, captivating.

His work can also be seen at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

SG

140. North Shore, Lake Superior (1926)

Lawren Harris (1885–1970)

Lawren Harris, North Shore, Lake Superior, 1926

Oil on canvas, 102.2 x 128.3 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Photo: NGC

Steve Martin, the polymath American entertainer, fell in love with Lawren Harris’s paintings years ago. He recently co-curated an art show, The Idea of the North, in Los Angeles, Boston, and Toronto. He is an eloquent missionary.

A picture like North Shore, Lake Superior, 1926, in the National Gallery, is his masterpiece. It is a very dramatic picture but he does something really wrong; he places the dead tree directly in the centre of the painting, which is a taboo. If it were a little bit off to the left or to the right, it would be a more balanced composition. It’s like painting a person and their head is at the top of the frame. But it completely works.

Lawren Harris has dead trees but they’re always backed up by a promise of sunlight and life and the sun rising, or the sun going down, but they are in the light. I think that’s Canadian. The depression is American.2

Martin spoke of serenity, isolation, resilience, and calm embodied in the hollowed-out trunk. I don’t agree. I see a struggle for survival in a hostile setting. I see isolation in a vast frigid space. I see the loneliness of the north. I see changeable weather — nice now, but it will change. I see the challenge of the north. A sensation of silence.

See the discussion of Harris in Chapter 16, on the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto.

JP

Hope I (1903)

Gustav Klimt (1862–1918)

Gustav Klimt,

Hope I, 1903

Oil on canvas, 189.2 x 67 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Photo: NGC

Hope I was and is a shocker. An eye-popping pregnancy pushing out under thin shoulder and frail arms. The official guidebook says the original studies portrayed a man standing with his arm around the girl in “an affectionate moment of contemplation.” Perhaps Klimt’s son, who died in infancy, changed his outlook. The model, Herma, had, according to Klimt, “… a backside more beautiful and more intelligent than the faces of many other models.”

Klimt meant to provoke and this painting accomplished that, so much so that he was persuaded by the minister of culture to withdraw the painting from public exhibition.

Pregnancy was not a subject of art at the time and the frankness of the girl’s look, with flouncy head and pubic hair, was beyond the pale.

There are three figures of disease in the background: old age and madness, a sea monster on the left with its large tail girdling her feet, and a skull above, a momento mori .

But the issue is “her look.” What is it? She’s not defensive. She’s certainly not embarrassed. It’s a bit of a gimlet stare. She’s impervious to our reaction. Something else is going on in her head and she’s suggesting we push off.

JP

141. The Evening Visitor (1956)

Jean Paul Lemieux (1904–90)

Jean Paul Lemieux, The Evening Visitor, 1956

Oil on canvas, 80.4 x 110 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Photo: NGC

Look at this image! Bleak, yet rich in details, stark, yet comforting in its self-sufficiency, this is a masterpiece of landscape and figure.

In his portrayals of the Québécois, Jean Paul Lemieux is among the most important postwar contemporary artists in Canada. His early works were inspired by the Group of Seven and the American Social Realist painters. His beautiful images reflected the people who came across his path, social studies on canvas. After a year abroad, on his return to Canada in 1955, Lemieux transformed his style from a more detailed painter into something iconic. Embracing a more signature approach, a cubist influence became evident in his stripped-down but immediate figures and vistas.

The Evening Visitor is one of many solemn monochrome landscapes he created. In his paintings from the 1950s onward, he interrupts his serene backgrounds with an eerie figure, often revealing emotion along the lines of fear, solitude, skepticism, or anxiety, trying to connect his subject and viewer, evoking the existentialism prevalent in that age. Here, a priest stands out against the snow, encompassing all that is Lemieux’s métier and for what he is today remembered.

Canada Post has issued commemorative stamps of his works, among them Self Portrait (1974), June Wedding (1972), and Summer (1959). Greatly admired by other Canadian artists and critics, Lemieux is also on display at the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

SG

142. St. Catherine of Alexandria (c. 1320–25)

Simone Martini (1284–1344)

Simone Martini,

St. Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1320–25

Egg tempera and gold leaf on wood, likely poplar, 82.2 x 44.5 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Photo: NGC

This was once the left panel of an altarpiece done in 1325!

The slender and melancholy saint looks tenderly at the Virgin and child in the centre. Legend has it she was a beautiful young Alexandrian lady who was pursued by Emperor Maximus, whom she rebuffed. She admonished him for his cruelties and his worship of fake gods. Maximus sent for pagan scholars to argue with her. They failed. He sent her to jail. She converted his wife. He ordered her to be broken on the wheel, but it was shattered by her touch. The headsman’s axe proved more fatal and her body was borne by angels to Mount Sinai.

Here she bears the horrific weapons that identify her. The wheel has been reduced to a brooch under her neck. She holds the pommel of the sword in one hand and a palm branch in the other — symbols of her martyrdom and spiritual victory.

Look at her pink cheek, the thin rivers of gold bronze hair, the eye-shadow, the implacable eyes, the gold chain emblems in the halo, the hands of a harpsichord player, the bejeweled trim of the gown.

Ahh, what delicacy! What grace! 1325.

Simone Martini was a prolific artist of paintings and frescoes. There are many of his works in Siena.

Giotto was master of Florence and the great creator of a new art, breaking away from the gold stylized Byzantine wooden figures. Siena veered somewhat from Florence and kept a bit of the artificial Byzantine style. I think Martini makes the Byzantine style alive, interestingly theatrical in colour and in pose, yet not necessarily “real.” Some view his figures as artificial, with convoluted poses and gestures, stylized faces without genuine emotion, everything bowing to a decorative effect. They view Martini as the final chapter of the past, whereas Giotto was the future.

I disagree. I think Martini is a precursor to Modigliani.

Perhaps, perhaps, but my, isn’t she beautiful?!

Martini was a friend of the poet Petrarch. He spent time in the Court of the Pope in Avignon.

JP

143. Voice of Fire (1967)

Barnett Newman (1905–70)

Barnett Newman, Voice of Fire, 1967

Acrylic on canvas, 543.6 x 243.8 cm National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa © The Barnett Newman Foundation, New York / SODRAC, Montreal (2017) Photo: NGC

Quelle horreur!

In 1990, twenty years after Barnett Newman’s death, the National Gallery of Canada announced it had bought Voice of Fire for $1.8 million, sparking an unheard of national debate about the meaning and value of art.

Conservative MP Felix Holtmann, chairman of the House of Commons communications and culture committee, famously said, “It looks like two cans of paint and two rollers and about 10 minutes would do the trick.” He isn’t remembered for anything else.

Others took a more nuanced view. Diana Nemiroff, who was the National Gallery’s contemporary art curator and is now director of Carleton University’s art gallery, defended the painting on CBC Newsworld , saying, “I wore a blue blazer with a red T-shirt underneath. It took a while before someone noticed.”

Shirley Thompson, then the National Gallery’s director, offered that, “You have to look at your understanding of the metaphysical dimensions of life.”

It’s a stunning piece of art, even more so today, in its spatial dimension and spirituality.

Russian, Poland-born Barnett Newman grew up in Manhattan and began drawing at the Arts League, where he met Adolph Gottlieb (see page 279). The well-connected Gottlieb introduced Newman to the vibrant art scene happening in New York at the time. Suffering through the Great Depression, he gave up art for a time, but in 1936, he became friends with gallery owner Betty Parsons, who began representing his friends Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, and Jackson Pollock. Once ensconced in this milieu, he resumed his painting career, but, as a conscious gesture, destroyed all his work to that date.

Suddenly, Newman found his niche. He began painting what he trade-marked as the “zip.” These paintings forged elements of Abstract Expressionism and minimalism. Voice of Fire is but one example. It encompasses simplicity, but evokes emotion and power. While it can be viewed at a distance, it invites a closer inspection. Yet, on first showing, Newman’s works evoked exactly no response from the viewing public. After a few poor showings, he withdrew from the gallery scene altogether. Instead, he focused on his art criticism and philosophical essays.

Showing that the art world and its appreciation is constantly in transition, he started to gain recognition in the 1960s, such that he returned to his craft, this time creating lithographs and sculpture. In 1966, he had his very first solo exhibition at the Guggenheim. Among other works, his Stations of the Cross series was on display, any one of which, like Voice of Fire , is too profound to be missed.

SG

144. Red Currant Jelly (1972)

Mary Pratt (1935–)

Mary Pratt, Red Currant Jelly, 1972

Oil on Masonite, 45.9 x 45.6 cm National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Photo: NGC

Jelly is not particularly difficult to make, and it seems to be a civilized and wholesome accompaniment to meat. It is as necessary to our kitchen as bread and butter. Because it is so beautiful — such a clear and brilliant reminder of its origins — we treat it with respect, given the major symbols of our culture. We set it, unmoulded and shimmering, on a crystal plate, transport it to the table with care, lay a silver spoon beside it and stand back and consider the pleasure it gives us.3

Red currant — what colour springs to mind? A red stronger than papal red? Perhaps, but here the currants are spiced with light, some darker, some lighter, one near ketchup. The chords of a bass viola, a bit of Bach, with the setting of tinfoil juicing it all up.

Would it work without the tinfoil? No. Red is usually a colour used as a startling companion to other colours. Here, the boldness of the red is the statement, but the frame is the unusual tinfoil, crinkly, play of reflected silver, silver blue, silver black, crevices, wrinkles, torn edges.

The daughter of a lawyer, politician, and judge in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Mary Pratt had a sheltered, structured, happy childhood. She went to Mount Allison University, close to Sackville. Reflecting on the words of one guest speaker at the art school, then director of the National Gallery, Pratt said, “He told us how wonderful ugly art was. I jumped up and said I haven’t led an ugly life. Do I have to go out and find one in order to paint?” The speaker retorted, “Oh, well, if you want to join the Mummy-Bunny School.”

Her Newfoundland husband, Christopher Pratt, quickly became a famous artist. She sketched, and gave birth to four children. She dabbled at sketching and Christopher Pratt took some photographs of a dining room scene in their Newfoundland house that she was trying to capture in fleeting light. The photographs were a revelation, catching things she hadn’t seen before.

Mary Pratt said of Chardin:

The painters I like the best are the seventeenth and eighteenth century genre paintings especially Chardin. I’d like to do as well by texture like tinfoil and saran wrap as they did by cottons and linens.4

This image just makes me smile.

JP

145. The Jack Pine (1916–17)

Tom Thomson (1877–1917)

Tom Thomson, The Jack Pine, 1916–17

Oil on canvas, 127.9 x 139.8 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Photo: NGC

To understand Canada is to understand Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven. Seeing this work and its resplendent companions should make one kvell with the pride of our country, its variegated beauty, and diverse natural heritage. If there were a synoptic shot of Canada from a period, one identifiable perspective, this is it. A forlorn tree in a silent vista.

Thomson was one of the two Canadians (Emily Carr, the other) who were extended parts of the Group of Seven artistic family — originally, Franklin Carmichael, Lawren Harris, A.Y. Jackson, Frederick Varley, J.E.H. MacDonald, Arthur Lismer, and Frank Johnston — that gave Canadian painters international renown. Thomson, Harris later said, “was part of the movement before we pinned a label on it.” Echoes of their work resonate in later Canadian artists, like Ralph Wallace Burton and William Goodridge Roberts.

Born in Claremont, Ontario, Thomson was heavily influenced by his cousin, Dr. William Brodie, a naturalist and the director of the biological department of what is now the Royal Ontario Museum. Thanks to the relationship between Brodie and Thomson, nature became the latter’s muse. In 1902 Thomson enrolled in business college and then transferred to a Seattle business school that was run by his brother. There, he was given his first job at a commercial art company doing engravings. This gave him the impetus and opportunity to show his artistic skills, and not long after, he moved to Toronto with the goal of becoming an artist full-time.

He enrolled in the Central Ontario School of Art and Industrial Design (now OCAD University). While studying, Thomson also worked at Grip Limited, a commercial art firm. At Grip, Thomson struck up friendships with the likes of J.E.H. MacDonald. In 1911, Thomson made his first trip to Algonquin Park as a wilderness guide, where he was smitten with his surroundings. The natural light radiating from the trees presented a challenge for Thomson. He wanted to be able to replicate it in his sketches and later his paintings. Falling in love with Algonquin, Thomson lived there in the spring and fall, sketching the ever-changing landscape. In winter, he returned to Toronto to turn the sketches into paintings, relying on his memory to do so.

The Jack Pine shows Thomson in his maturity. Flat panels of colour transluce through the imagery but maintain constant movement, enhanced by the striation of the horizontal brushstrokes. The droopy trees look slightly unnatural and resigned, winter is coming or has been here. As he had to rely on his imagination, the painting is in a way more evocative than if it were a mere replication of the scene before him.

Shrouded in mystery, Thomson drowned in Canoe Lake the same year that he completed Jack Pine. But Thomson’s legacy is still alive, at least in Canada, brought to full life in the film West Wind: The Vision of Tom Thomson (2012). In artistic terms, Thomson is a manifestation of the magnificence of this country.

SG

Also in the gallery, there are about thirty-two of Tom Thomson’s small oil on panel (8.5 in x 10 in) sketches. They represent what was the central theme of the great Canadian landscape painting. In a word — weather. Yes, weather. All kinds of it, everywhere. You can’t escape weather in Canada and its variations are a delight in an often-barren land.

See the clouds, the lightning, the sunset clouds, cirrus clouds, coming storm, far-off rain, peaks of blue, sunny day blue. Not a human in the works. Other than the birch trees, very little is still. Weather here is on the move. Storm’s coming, let’s get moving.

This is the best possible analysis of Thomson, all a product of the outdoors, all instinctive, combining talent and the accumulation of experience.

He died young, very young.

The paintings are on a variety of available materials: plywood, wood, wood-pulp board, cardboard. They fit in a small wooden sort of briefcase with slots, so when the paintings were put in it, they didn’t rub each other and smear the paint. The briefcase was placed in the canoe with a grub box, axe, bedroll, and a groundsheet.

JP