Chapter 6

Detroit, Michigan

Detroit Institute of Arts

33. The Wedding Dance (c. 1566)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525–1569)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Wedding Dance, c. 1566

Oil on panel, 119.4 x 157.5 cm

City of Detroit Purchase (30.374)

Detroit Institute of Arts

Photo Credit: Detroit Institute of Arts / Bridgeman Images

Look at the Wedding Dance by Pieter Bruegel. The painting is part of a trilogy on marriage and partying. The bride, with a frizzy mop of hair, appears in paintings in Vienna.

I love the rhythm of this picture and aren’t those codpieces a hoot? They’re everywhere and they are huge! They weren’t a sexual boast primarily, you could remove it easily and relieve yourself!

Dancing, at the time, was viewed by church and the authorities as a vice. Here it is jolly — earthy, that’s the word, earthy. I love the thrust of the women’s hips, the sway of the backs. In the lower corner is a bagpipe, called a pizzle.

Off against the tree at eleven o’clock something’s going on. What is it? Look, look at the slobbery kiss before the pensive viewer (Bruegel himself?). Isn’t the man on the lower right copping a feel of a woman behind him?

Come on, get here quickly, there’s a riotous party!

JP

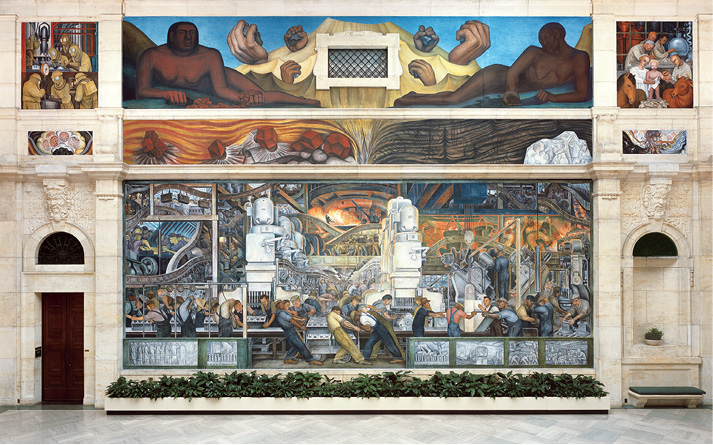

34. The Detroit Industry Murals (1932–33)

Diego Rivera (1886–1957)

Diego Rivera, The Detroit Industry Murals, North Wall, 1932–33

Fresco

Gift of Edsel B. Ford (33.10.N)

Detroit Institute of Arts

Photo Credit: Detroit Institute of Arts / Bridgeman Images

Diego Rivera was a communist. Trotsky had been a frequent guest at his house in Coyoacán, outside Mexico City. So, it was strange that Edsel Ford, son of Henry Ford, sent an invitation to Rivera to do murals on capitalism’s symbol, the motor-car assembly process.

Well, I must tell you the result is a thumping, roaring success. From April 1932 to May 1933, he did four frescoes to fill a courtyard (the centre of the museum).

When you go through the predictable paintings of Europe and America, you arrive at a flat, colourful rhythm of work and bustle. The courtyard is separate so you must concentrate on it. You receive a free, hand-held video presentation which I think is the best art-aid I’ve ever enjoyed. It explains all and shows films of Rivera actually painting the frescoes. I’ve read of fresco-making forever and yet have been a bit unsure — this video actually makes clear the mechanics of fresco-making.

The original concept was to show how a car was produced and glorify the role of the worker in the industrial process. The murals accomplish this in paint, but the fascinating subtext is that Rivera is painting the owners as monsters.

Edsel paid Rivera $20,000 for his work, upping the total in the middle. Also, one of Ford’s banks went broke and his first cheque got gobbled by the bank’s default, so he had to pay again. The unemployed American artists in the early 1930s were not amused that a Mexican communist got this plum assignment and that there may well have been a dab of public money going offshore. Rivera and his famous wife, Frida Kahlo (who was wildly unhappy living in Detroit), stayed for almost two years. Rivera studied assembly lines at Ford plants and other industrial sites.

Let me talk of the poetry in this vast work. His portrayal of the assembly line on the north wall, with its workers bending, arms pressuring down on the car parts, heads together in a confluence of work, rhythm, and sweat. Above them, a conveyor belt linking the ballet of work.

The car factory was a city unto itself: one-and-a-half miles wide, one mile long, with 120 miles of conveyor belts. Some workers rarely left and there were even places in this “city” where they could buy Christmas gifts, as they had so little time. They were paid $5.00 a day — a fortune at the time (equivalent today to $200). But this beneficent employer sent detectives to the workers’ households and, if there was evidence of smoking in the house, they were out. Presto! No unions here! Yet Rivera was glorifying a concept that he must have resented. Surely the least Rivera stood for was the right of a union.

This is a panorama of the intricate spirits of honest work and a paean of praise to the larger systems of industry. Why do I see the evil theme? The video doesn’t accentuate it. It is my impression.

The First World War produced factories, planes, and gas for war’s purposes. Rivera shows the insect, science-fiction workmen, enclosed in gas masks, making poison gas bombs — a dreadful memory of gas and lifelong convalescence without end. There are more mounting planes revving up for war and death.

There is a pale green-blue cast on the faces of workers mixing sand for the making of moulds. The fiery furnace ascending to the volcano on top of the mural, an explosion ready to pop through a volcano encased in clenched hands, salutes of resentment.

Rivera obviously was given carte blanche .

He portrayed a baby being vaccinated, replicating a Renaissance Madonna and child theme. Fair enough, but the Madonna was a dead ringer for the famous Hollywood actress Jean Harlow (companion of Clark Gable) and the infant (Jesus) a replica of Lindbergh’s kidnapped son.

Ten thousand jammed the Detroit Institute of Arts on March 26, 1933, for the opening of the murals. The vaccination panel drew complaint from the Detroit religious community as sacrilegious and “one subtle blasphemy” a caricature of the Holy Family.

Whitewash the walls, the critics demanded.

Edsel countered: “I admire Rivera’s spirit. I really believe he was trying to express his idea of the spirit of Detroit.” He persevered.

March 18, 1933: The Detroit News called the frescoes, “coarse in conception … foolishly vulgar … a slander to Detroit workmen … un-American.”

From January through March 1933, labour strikes paralyzed the auto industry. On February 15, Detroit’s banking system collapsed, failures of banks erupted.

Rivera gave poetry and dignity to workers in their rhythmical work, but I see a theme of last judgment to it in the volcanic fire at the top, poison masks, planes of war, workers green in pallor.

JP

Gamblers Quarreling (c. 1665)

Jan Steen (1626–79)

Jan Steen, Gamblers Quarreling, c. 1665

Oil on canvas, 70.5 x 88.9 cm

Gift of James E. Scripps (89.46)

Detroit Institute of Arts

Photo Credit: Detroit Institute of Arts / Bridgeman Images

Whoopee!!!!!

The blood is up — the brawl is on!

Jan Steen followed the era of Rembrandt. A tough act to follow, to put it mildly. I chose this painting because it is a pure boozy brawl, all fist, belch, and curse. Steen owned an inn so he could observe first hand. Usually Steen is more precise and subtle with quiet hints tucked away in domestic scenes, revealing cuckoldry or the like. Here no subtlety. If someone casually says, “There’s a little Steen in the next room which is worth a look,” run, don’t walk.

JP

The Jewish Cemetery (1654–55)

Jacob Isaacksz van Ruisdael (1628–82)

Jacob Isaacksz van Ruisdael, The Jewish Cemetery, 1654–55

Oil on canvas, 142.2 x 189.2 cm

Gift of Julius H. Haass in memory of his brother Dr. Ernest W. Haass (26.3)

Detroit Institute of Arts

Photo Credit: Detroit Institute of Arts / Bridgeman Images

Van Ruisdael was the leading Dutch landscape painter of the second half of the seventeenth century. (A sad man, also a surgeon.)

This very large work on canvas (56 in x 74 in) — just bustles with the energy of a stage play.

Rain, storm clouds, ruined Romanesque church, lightning, birch, gurgling water, pale rainbows, all in a dark light This is a fanciful Portuguese-Jewish cemetery in Amsterdam, where neither hills nor a Romanesque church existed.

The guidebook prattles on about the symbols in it. The marble tomb smack in the centre is reduced to “marble tombs memorialize people’s lives yet remind us of death’s inevitability” or “the flowing stream is a symbol of life and the rainbow, in biblical terms, is God’s covenant with Noah, after the flood.” Give me a break! This painting is a sweeping Tchaikovsky, all vibrato, violins, melodrama. The play is about to begin OR the play is ended and we’re off to a nether world.

This painting is lush and has pop.

You would need a big wall for this.

JP

35. Nocturne in Black and Gold, the Falling Rocket (1875)

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Nocturne in Black and Gold, the Falling Rocket, 1875

Oil on panel, 60.2 x 46.7 cm

Gift of Dexter M. Ferry Jr. (46.309)

Detroit Institute of Arts

Photo Credit: Detroit Institute of Arts / Bridgeman Images

In 1877, London, England, was dominated in social circles by two electric gentlemen: Oscar Wilde and James McNeill Whistler. Whistler was born in America, left for Paris at twenty-one (all 5 ' 3 " of him), trained in Paris Bohemian art life, and was the spitting image of Mark Twain.

Oscar Wilde said of him, “Mr. Whistler always spelt art and we believe still spells it with a capital ‘I,’”

In the summer of 1877, Sir Coutts Lindsay, a wealthy English banker and art lover, organized an exhibition of paintings by the leading contemporary artists in the Grosvenor Gallery, London, which he had founded in opposition to the more conventional Royal Academy. The exhibition, which attracted a great deal of publicity, became a focal point for art critics as well as avant-garde artists. It was the subject of a complimentary notice by Oscar Wilde, who was a frequent visitor, and a fiercely critical one by John Ruskin, then Slade Professor of Art at Oxford and the acknowledged leader of the popular conservative school of art criticism. The American Impressionist painter James McNeill Whistler was singled out as a particular object of attack by Ruskin, who wrote:

For Mr. Whistler’s own sake, no less than for the protection of the purchaser, Sir Coutts Lindsay ought not to have admitted works into the gallery in which the ill-educated conceit of the artist so nearly approached the aspect of wilful imposture. I have seen, and heard, much of cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.1

Why the fuss?

The picture itself (1875) is now at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Whistler created an indeterminate flash of fireworks falling and rising in the night without any reference to a figure or a solid building. This done in a time when rather exact camera-like pictures held sway. This picture all dark, flash, and sparkle, but in the Park Cremorne, which had a shady reputation where sexual activities flourished.

Ruskin was a famed conservative art professor in his sixtieth year.

Whistler sued Ruskin for libel in 1877. In November 1878, Ruskin suffered a mental breakdown before the trial began and was unable to participate. He was deemed unfit to stand trial.

Whistler’s lawyer argued, “the terms on which Mr. Ruskin has spoken of Mr. Whistler are unfair and ungentlemanly and are calculated to have done him considerable injury and it will be for you gentlemen of the jury to say what damages Mr. Whistler is entitled to.”

The Falling Rocket was initially exhibited to the jury upside down as the court clerk handed it forward.

Whistler was cross-examined by Sir John Holker, the attorney-general, with a lucrative private practice, who represented Ruskin:

Attorney-General: Did it take much time to paint the Nocturne in Black and Gold ? How soon did you knock it off? (Laughter )

Whistler: I beg your pardon.

Attorney-General: I was using an expression which was rather more applicable to my own profession. (Laughter ) How long did you take to knock off one of your pictures?

Whistler: Oh, I knock off one possibly in a couple of days — one day to do the work and another to finish it. (Laughter )

Attorney-General: And that was the labour for which you asked two hundred guineas?

Whistler: No; it was for the knowledge gained through a lifetime.

Attorney-General: You have made the study of art your study of a lifetime. What is the peculiar beauty of that picture?

Whistler: It is impossible for me to explain to you the beauty of that picture as it would be for a musician to explain to you the beauty of harmony in a particular piece of music if you have no ear for music.2

One of the witnesses for Ruskin was Tom Taylor:

The third and final witness for the defence was Tom Taylor, editor of Punch and for many years art critic of The Times and The Graphic. He said that he had seen Whistler’s pictures in the Grosvenor Gallery, and he confirmed the opinion of Frith and Burne-Jones that “The Falling Rocket” was not a serious work of art.… “All Mr. Whistler’s work is unfinished,” said Taylor. “It is sketchy. He, no doubt, possesses artistic qualities, and he has got appreciation of qualities of tone, but he is not complete, and all his works are in the nature of sketching. I have expressed, and still adhere to the opinion, that these pictures only come ‘one step nearer pictures than a delicately tinted wall-paper.’”3

The jury returned and found for Whistler but awarded the lowest coin of the realm, a single farthing, as damages. Whistler put the farthing on a chain around his neck.

Whistler had to pay his lawyer’s costs of £500. This and other debts forced him into bankruptcy.

Ruskin resigned as Slade Professor of Art at Oxford because of the judgment and his condition.

Whistler’s view of art as harmony, his night studies as nocturnes, with the emphasis on abstract, is modern art.

Well, what does this actually look like? My first impression is one of ingots showering from a smelting oven. Also quite muddy, all muddy. But, when I stand back a good distance from it, there is a sense of place and a revelation of bubbling, flickering light.

Whistler shouldn’t have brought the suit; Ruskin was a bit over the top. Definition of coxcomb? “The comb resembling that of a cock formerly worn by Jesters; a conceited person, a fop, a dandy.”

JP