Chapter 16

Toronto, Ontario

Art Gallery of Ontario

Frank Gehry, noted for his free-standing new buildings, worked with the existing structure of the Art Gallery of Ontario, hemmed in by old buildings of commerce and homes. His billowing glass façade straddles a commercial street. It has the verve of a spinnaker riding high over the smooth curve of a yacht hull. Inside, Gehry has created the Galleria Italia, overlooking the entire block. The vaulted pine ribs sweeping up — a modern Gothic nave. At the base, you enjoy coffee, ice cream, the view of a vibrant city street and touch the flowing ribs. Outside, light and a city street with architecture of past houses.

In the middle of the gallery, Gehry placed a Douglas-fir sculptural stairway, rising up, soft to the eye with a feel of smooth, twirled ice cream in a cone.

Gehry evokes delicacy and romance. Rare.

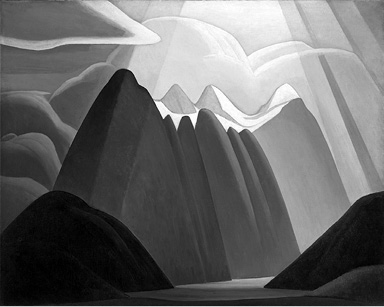

Untitled Mountain Landscape (c. 1927–28)

Lawren Harris (1885–1970)

Lawren Harris,

Untitled Mountain Landscape, c. 1927–28

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

I am distantly related to Lawren Harris, though I never met him, as he left Canada before I was born. Yet he was an influence in my home. We lived on a hill above Lawren Harris’s studio (just where the Toronto Yonge Street subway breaks into the open air north of Bloor Street). In the garden, A.Y. Jackson lived in a rustic cabin. Tom Thomson’s cabin was there until 1952 and Jackson lived in that. Jackson was close to Thomson. He gave my brother Dana art lessons when he babysat me.

My great uncle Chester had a number of Harris paintings — dark and serene pools of water enveloped in lush foliage. Unfortunately, none of them found their way to me.

Harris was born into a wealthy family — connected to the Massey-Harris Company. As a young man, he travelled extensively through Europe, traversing the continent from 1903–1907, studying art. He spent considerable time in Berlin. German artists of the period believed the land and climate influenced the citizens’ concept of their home. Harris was convinced that our northern wilderness with its snow influenced the spirit of Canadians.

He enlisted in the navy in 1916, but he suffered a nervous breakdown while in service. He was subsequently discharged.

On his return to Canada, he began to pursue a career as an artist. He admired Tom Thomson’s West Wind and Jack Pine , done in 1917. He travelled to Algoma and his spirits lifted. In 1918, he arranged for the Algoma Central Railway to supply him with a freshly painted box car with all the fixings, first class, and he took artists from the Group of Seven along. He arranged six more trips. The railway car had a hand car that would allow them to take off by themselves.

Harris was the leader of the Group of Seven artists, who all concentrated on landscape. They despised their contemporaries among Canadian artists, who followed British styles. The group believed these styles to be completely out of date and muddy.

His early small paintings from 1918 are lush (Falls Agawa River , 1918) and a version of Impressionism akin to Cézanne (Algoma Sketch XXXI , 1920–21).

A.Y. Jackson, a partner on some of these train trips, said, “The Algoma country was too opulent for Harris; he wanted something bare and stark.”

Well, Superior had suffered fires and there were plenty of burnt stumps about, so in the large Harris Room, on one side are the stark paintings of the north, Superior, Alberta, and Mount Robson. Some critics were appalled at the smooth, evenly painted canvases, stark, without a sense of detail. He later went to the Rockies, where he rendered the mountains as simple, powerful forms partly flooded with a divine light — God’s rays.

These paintings seem soothing, cool, smooth sculptures.

In the early 1900s, there was a religious philosophy, theosophy, which posited that spiritual revival would emanate from the north. The snow, the purity, the bright light evoked the divine presence.

Harris’s view:

Because of their proximity to the Arctic, Canadians, he asserted, had a special role to play in the spiritual evolution of humanity. In a 1926 essay, “Revelation of Art in Canada,” published in Canadian Theosophist, he had written: “We are on the fringe of the great North and its living whiteness, its loneliness and replenishment, its resignations and release, its call and answer — its cleansing rhythms. It seems that the top of the continent is a source of spiritual flow that will even shed clarity into the growing race of America, and we Canadians, being closest to this source, seem destined to produce an art somewhat different than our Southern fellows — an art more spacious, of a greater living quiet, perhaps of a certain conviction of eternal values. We are not placed between the Southern teeming of men and the ample, replenishing North for nothing.”

His startlingly original view of landscape fascinates. But the issue is this: would you get bored with it?

The group had a struggle but they were not met by the kind of vehemence hurled at the Impressionists in France. There were some outspoken critics, but the cultural elite supported them and their works, and reproductions were widely distributed to schools. However, they didn’t sell many of their works.

There is a vast room in the gallery that allows you to compare Harris’s earlier work, his city work, with the stylized flow of mountains and single, bare limbs of trees.

This Untitled Mountain Landscape is haunting. A vision of Valhalla with dark varieties of purple, cobalt blue, dark taupe, deep lilac set off against a green foreground. The molar ribs’ slight variation of purply related colours strike a musical chord.

Many viewers prefer the small, early panels on the opposite side. They also take to his Winter Afternoon, City Street, Toronto (Sunday Morning) (1918). A picture of a city house, splashed with snow, lush trees, a feeling of Christmas bells.

Close by is his South Shore, Bylot Island.

JP

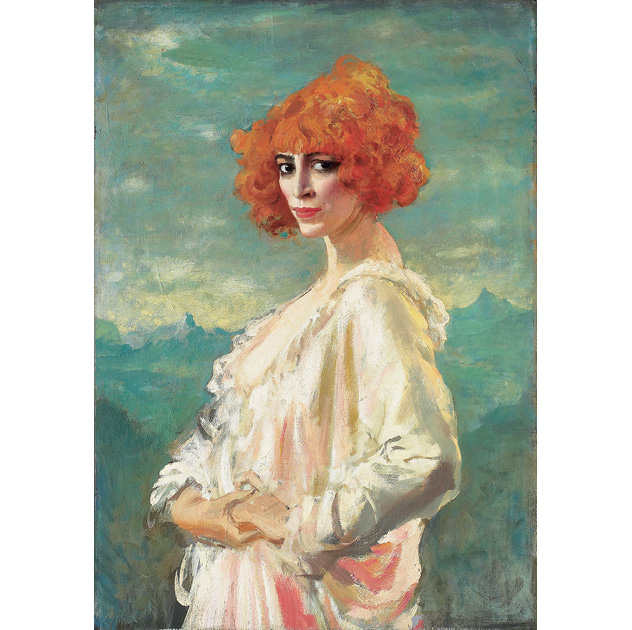

146. The Marchesa Casati (1919)

Augustus John (1878–1961)

Augustus John, The Marchesa Casati, 1919

Oil on canvas, 96.5 x 68.6 cm

Purchase, 1934

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Photo credit: Art Gallery of Ontario / Bridgeman Images

What a beautiful image! The fiery red hair, the come-hither look. Striking, magnetic, magical.

English-born Augustus John was a celebrated portraitist in the early to mid-1900s. At the Slade School of Art in London, John tried to merge Impressionism with Mannerism, the latter an emphatic use of line and hue to accentuate the features of the subject.

After his studies, John travelled abroad, becoming exposed to the famous portraitists, such as Rembrandt and El Greco, known to the cognoscenti and casual viewer alike. Their influences can be seen in one of his most famous portraits, The Marchesa Casati . The Marchesa was a prominent Italian heiress of the day, known for her buoyant, effusive personality, who captivated the world around her but died in relative poverty.

The Marchesa Casati emphasizes not only the Marchesa’s coquettishness, but also John’s painterly style. Standing tall against a wash of light blues and pinks, is she gazing at us or something in the middle distance? Is she tempting John or us, or both?

In her deep, darkly set eyes, one can catch the Impressionist influence. As the viewer’s gaze shifts from the bottom to the top of the painting, the colours gradually lighten, depicting a mountainous background against a light sky. The middle of the painting holds a lighter wash of colour, neither blue nor pink. Sunset, perhaps, or early evening?

John did three paintings of the Marchesa, this being the most popular. His legacy, though, includes portraits of many influential English figures, such as W.B. Yeats and Winston Churchill.

John’s work may also be seen at the Dalhousie Art Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

SG

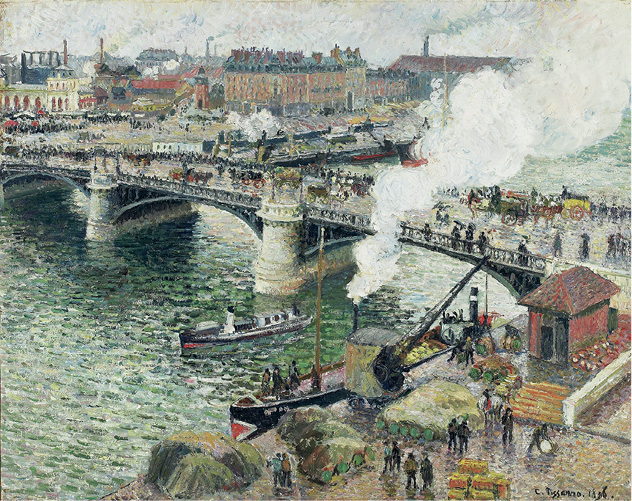

147. Pont Boieldieu in Rouen, Rainy Weather (1896)

Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)

Camille Pissarro, Pont Boieldieu in Rouen, Rainy Weather, 1896

Oil on canvas, 73.6 x 91.4 cm

Gift of Reuben Wells Leonard Estate, 1937

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Photo credit: Art Gallery of Ontario / Bridgeman Images

You should always look at a good Camille Pissarro and remember he was the undisputed leader of the Impressionists, although never as successful as the others.

Pissarro painted outdoors with Cézanne from about 1875 to 1885. They painted side by side. But Pissarro led, Cézanne followed, and became more disciplined. He moved Cézanne from an anguished portrayer of awkward bodies to outdoor painting and an ability to focus on landscape with a keen discipline. Pissarro taught him to watch the whole panorama and put emphasis on certain aspects. Cézanne took to structures as a focus and concentrated on forms, reducing them to essentials, creating starker images, prominent, often created with a palette-knife. Cézanne wrote, “Pissarro was like a father to me: he was a man you turned to for advice and was something like le bon Dieu.”

The differences of approach — Pissarro favoured a more panoramic view and tended toward the descriptive, yet with a structural sense.

Pissarro was no less prominent at the time. Émile Zola wrote highly of him. His dealer, Durand-Ruel, sold eight hundred of his paintings. The other Impressionists all thought well of him. He was a leader.

He organized an exhibition in April 1874. Degas had ten pieces in the show, Monet nine, Morisot nine, Renoir seven, Sisley and Pissarro five, Cézanne three. Imagine how many people would come today! Then, only 3,500 people came (over four weeks) and they came but to jeer. That was when the derisive term “Impressionists” was born. The sales were disastrous and the art dealers, including Durand-Ruel, backed off supporting them for almost five years.

This painting has the sense of city, energy, and motion. He was successful, in the league of Monet and Renoir.

Look at the detail. A whole town, a huge number of people on the bridge, the figures indistinct, rendered by a quick dab of the brush. It’s hard to imagine more detailed yet more fudged people.

Pissarro wrote his son:

I think I shall stay here until the end of March, for I found a really unusual motif looking out of one of the hotel rooms facing north. (It’s ice cold and has no fireplace). Just imagine it: the whole of old Rouen seen from above the roofs, with the cathedral, St-Ouen’s Church and the fantastic roofs and really amazing turrets of the city.

Look at the variety of colour in the architecture of the big harbor town. How is this massive bridge held in check by an empty space of green water?

The energy of commerce is captured.

Pissarro spanned the second half of the nineteenth century, from Courbet to Fauvism at the turn of the century. He was a prodigious producer. He tried many styles and was influenced by Seurat’s Pointillism.

In 1906, his last year, Cézanne eulogized his comrades of former years: “Monet and Pissarro were the two great masters, the only ones.” In the catalogue of his exhibition in Aix in that last year, he humbly described himself as “Paul Cézanne, pupil of Pissarro.”

JP

Portrait of a Lady with a Lap Dog (c. 1665)

Rembrandt (Rembrandt van Rijn) (1606–69)

Rembrandt

(Rembrandt van Rijn), Portrait of a Lady with a Lap Dog, c. 1665

Oil on canvas, 81.3 x 64.1 cm

Bequest of Frank P. Wood, 1955

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Photo credit: Art Gallery of Ontario / Bridgeman Images

Ah Rembrandt! My passion. I talk so much about him that I must apologize.

Look, if you talk of music, you must, you absolutely must, mention Mozart, Verdi, Beethoven, even Bach; so it’s the same with art. There are some towering masters — surely Rembrandt, surely Titian, and a whole spate of Italians — never mind Goya and Velázquez.

So here in the AGO is a Rembrandt — one.

I saw this painting as a kid at the house of the donor, a Mr. Frank Wood, who lived around the corner from us.

A stupid-looking lap dog, which one would think could trivialize the whole picture. Not so.

At first it seemed only an innocuous painting, done near the end of Rembrandt’s life (1665), when bankruptcy and the death of his dear son, Titus, pressed on him. Initially, your impression may be of a mindless, pampered sitter — a product of wealth — BUT — look closely — look! First the roughened palette-knife creation of her blouse, a blur, a furry blur, that from a distance “takes substance.” The pearls, all with a flick of white, the glint of light or the glint of the internal life of the pearl. Pearls have a shine. Red cheeks, curly hair, and the eyes — look again at the eyes. Look at the slash of white on her sleeve. The ruddy red of the dress to the eyes. The eyes have it. Are they immature? Or are they remarkably subtle? Look.

If you were younger, might you not fall in love with the deep well of her eyes? If you did, a mistake, I fear. Not much fun and a little too judgmental. Look up close at the puppy dashed off, yet its eyes have a liveliness.

How can a painter do this with a dob, or dab, of a brush?

This painting was included in the great Rembrandt show in the National Gallery in London in 2014.

JP

148. The Massacre of the Innocents (c. 1611–12)

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

Peter Paul Rubens, The Massacre of the Innocents, c. 1611–12

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

This painting was donated by Lord Kenneth Thomson. He paid £70 million for it. It is technically incomparable, the skin alive, the slaughter realistic.

King Herod ordered all boys, under two years of age in the vicinity of Bethlehem, be slaughtered.

The scene: eleven kids dead, dying, some still moving. Never was the feel of thrust of a sword more jaw yanking, with the old dying lady holding the blade as it slashes her palm. The live babies all a glisten and wriggle while the dead flesh moves from ivory to grey. The man on the right — huge — lifting a baby up to crash it down on the marble pediment. Your head averts — you turn to escape the gore and brutality.

It is quintessential gore. I have seen women come to this painting, they turn, focus, focus again, and once they understand it, they turn away, hand to mouth.

Most of the painters of the time took a run at this subject.

It used to hang over a fireplace in an Antwerp house, meant to be viewed from the far-right side (standing before it) giving it more of a motion picture effect. A baroque, over-the-top painting, all operatic boffo, as realistic as television wrestling or a Schwarzenegger movie, all pretend, glorious, surreal violence. Orthodox Jewesses were not in red silk dresses, with exposed bare shoulders. Bethlehem was just a village then, as now, not a city stage set. And Roman soldiers really did wear clothes. It is all an action movie. Ready, action, start the camera rolling!

Rubens, a towering giant in art, in league with Rembrandt and Michelangelo. A prodigious worker, dominating Antwerp, and a diplomat to boot. He loved the portrayal of flesh.

JP

Winter Thaw in the Woods (1916)

Tom Thomson (1877–1917)

Tom Thomson, Winter Thaw in the Woods, 1916

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

The wall has, on both sides, a running double panel of twenty-five paint boards by Tom Thomson, reflecting preoccupation of art on north sky’s weather, trees, and water — the three sisters of the Canadian north.

This painting (21.6 cm x 26.8 cm) best shows Thomson’s method of sloshing tubes of paint on a painting. The melting snow, rivers of smeared, white, trowelled meringue, cake icing, setting off the Copenhagen blue and the barked trees with a variety of Cézanne colours. The sheer glee of slapping on rivers of ribbed white paint, a life of its own, a sense of gloop, gloop, gloop.

See a similar Thomson room in Ottawa’s National Gallery, which captures the spirit of the Group of Seven. Also, Thomson’s Jack Pine is discussed on page 424.

JP

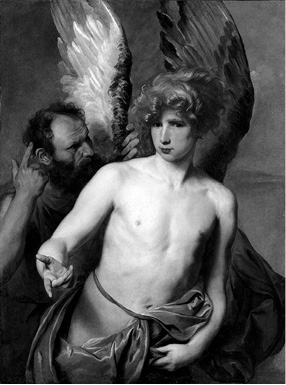

Daedalus and Icarus (c. 1620)

Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Sir Anthony van Dyck,

Daedalus and Icarus, c. 1620

Oil on canvas, 115.3 x 86.4 cm

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frank P. Wood, 1940

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Photo credit: Art Gallery of Ontario / Bridgeman Images

A strange Van Dyck here. The artist, who lived only to the age of forty, was a prodigy, a worker, a genius. He created the fashion of elegant portraiture, emphasizing many shades of black, elongating figures, creating beauty, sometimes from the ordinary. But this is not one of his conventional portraits (see Marchesa Balbi on page 377).

This tells of the myth of Icarus. Daedalus, the inventor, built a labyrinth for King Minos. Later, Minos imprisoned Daedalus and his son, Icarus, in the labyrinth. Daedalus made wings for himself and Icarus. He urged Icarus, “Don’t fly too close to the sun.” They both escaped and Icarus didn’t listen and fell to his death. Here, a beguiling Icarus with a mop of blond hair, a scattered life of its own, a mouth in pre-pout, a tender youth listening to unsolicited counsel, his eyes with the glint of suspicion. The pupils different in angle and focus. The slim emerald green strap fails in its task of camouflage — erotica comparable to Donatello’s David . A mirror of seductive puberty.

Daedalus hectoring, grasping one wax wing, the white one, different than the grey one, the wings a startle.

Was ever youthful uncertainty or other agenda better portrayed?

JP