4

Wittgenstein and Frege

MICHAEL BEANEY

1 Introduction

Of all philosophers, it is Frege whom Wittgenstein held in greatest esteem. In the preface to the Tractatus, in commenting on the influences on him, he remarked that “I will only mention that I am indebted to the magnificent writings of Frege and the work of my friend Mr Bertrand Russell for a large part of the stimulation of my thoughts.” Wittgenstein soon became disappointed by the reception of the Tractatus by both Frege and Russell, but whereas his relationship to Russell became more and more strained as the years went by, he retained his respect for Frege’s writings to the very end of his life. At Cornell in August 1949, for example, he was still reading and struggling with Frege’s most famous essay, “Über Sinn und Bedeutung” ([1892a] 1997; WC 18, 25–7; WAM 70). When J.L. Austin’s translation of Frege’s Foundations of Arithmetic was published in 1950, Wittgenstein discussed it with Ben Richards on a trip to Norway (Kienzler, 2011, p.81, n.7). Just two weeks before his death on 29 April 1951, in the last of the notes published in Culture and Value, he remarked that “Frege’s style of writing is sometimes great” (CV 87).

That Wittgenstein admired Frege’s writing style is perhaps unsurprising. The aim of philosophy, Wittgenstein wrote in the Tractatus, “is the logical clarification of thoughts” (TLP 4.112), a characterization that might well be taken to be true of Frege’s philosophy. The clarity that Wittgenstein saw as an important philosophical virtue is arguably nowhere better illustrated than in Frege’s writings, even if one disagrees with the substantive philosophical claims that Frege makes. Peter Geach reports a remark that Wittgenstein made to him when they were discussing Frege’s essay “On Concept and Object”: “How I envy Frege! I wish I could have written like that” (LPP xiv). That this remark should be made about this particular essay is significant. It counts as the most “elucidatory” of all of Frege’s writings, and the notion of elucidation (Erläuterung) was of crucial importance to both Frege and Wittgenstein. If Wittgenstein is right that “A philosophical work consists essentially of elucidations” (TLP 4.112), then “On Concept and Object” is a paradigm.

Wittgenstein may have envied Frege’s style, but he nevertheless felt it had a strong effect on his own writing. In a remark published in Zettel, again dating from the last years of his life, he wrote: “The style of my sentences is extraordinarily strongly influenced by Frege. And if I so wanted, I could most likely establish this influence where no one at first sight would see it” (Z 123). Wittgenstein does not elaborate on this, but someone’s first impression might well be that the aphoristic style of his own writing shows no obvious trace of Frege’s influence. On deeper comparison, though, the clarity and elucidatory quality of Frege’s writings does indeed come through, and maybe this is what Wittgenstein meant (see also Chapter 2, WITTGENSTEIN’S TEXTS AND STYLE).

Whatever speculations might be offered about this, however, Frege’s influence on Wittgenstein is far more profound than matters of style, even allowing for the inclusion of elucidatory qualities. Most importantly, Wittgenstein found in reading Frege’s work a continual source of philosophical problems with which he grappled obsessively from the moment when he was first trapped in the fly‐bottle. It was the paradox that Russell discovered in Frege’s logicist project that drew Wittgenstein seriously into philosophy; and another remark that Geach reports illustrates how fascinated Wittgenstein became with Frege’s views:

The last time I saw Frege, as we were waiting at the station for my train, I said to him “Don’t you ever find any difficulty in your theory that numbers are objects?” He replied “Sometimes I seem to see a difficulty – but then again I don’t see it”.

(Geach, 1961, p.130)

Wittgenstein never held that numbers are objects, but he was intrigued as to what led someone as sharp as Frege to take that view.

Frege is explicitly cited as an influence on the Tractatus, but although he is rarely mentioned by name in his later writings, his views continued to be a major source of inspiration to the very end of Wittgenstein’s life. O.K. Bouwsma reports on what Wittgenstein told him in talks they had about Frege in August 1949: “Frege is so good. But one must try to figure out what was bothering him, and then see how the problems arise. There are so many of them” (WC 27). To identify these problems and understand how Wittgenstein tried to diagnose them is virtually to provide a complete account of the development of Wittgenstein’s philosophy. All I can do here is indicate some of those problems and some of his responses, in both his early and his later work. First, however, I will say more about the relationship between Wittgenstein and Frege from Wittgenstein’s first encounter with Frege’s ideas.

2 Wittgenstein’s Relationship with Frege

Wittgenstein probably first became acquainted with Frege’s work in late 1908 or early 1909, when he was a student of aeronautical engineering at Manchester. The standard story is that he attended J.E. Littlewood’s lectures on mathematical analysis, and joined a group of fellow students interested in the foundations of mathematics, which led him to Russell’s book The Principles of Mathematics (1903; Monk, 1990, pp.28–35; Reck, 2002, pp.4–6). That book has two appendices, the first on “The Logical and Arithmetical Doctrines of Frege” – this was the first reasonably substantial exposition of Frege’s philosophy to appear in English – and the second on “The Doctrine of Types,” Russell’s first attempt to solve the paradox that he had discovered in Frege’s work. Wittgenstein was hooked by the paradox, and in April 1909 he wrote to Philip Jourdain in Cambridge offering his own solution. Although Jourdain – with Russell’s endorsement – rejected that solution, Wittgenstein continued to work on his philosophical ideas. He read some of Frege’s writings, at the very least parts of Grundgesetze der Arithmetik (1893/1903), and according to his own account, made some criticisms, which he sent to Frege himself, asking if he could visit him (Geach, 1961, p.129; cf. RW 2).

Wittgenstein’s visit to Frege in Jena in summer 1911 was of decisive importance to his philosophical career. In their discussions, as Wittgenstein reported on more than one occasion (Geach, 1961, p.130; RW 110, 214), Frege “wiped the floor” with him but nevertheless invited him to come again. More importantly, bearing in mind that Frege was by then in his sixties and suffering from ill health, Frege recommended that Wittgenstein go to Cambridge to study with Russell. Thus it was that Wittgenstein turned up, unannounced, at Russell’s rooms in Cambridge on 18 October 1911, and began attending Russell’s lectures and discussing philosophy with him. He officially registered as a student at Cambridge in February 1912. Wittgenstein worked with Russell until October 1913, when, having left some “Notes on Logic,” he went off to Norway to live by himself. He was back in Vienna the following summer, and when World War I broke out, enrolled in the Austrian army. During this period, he visited Frege at least twice more, in December 1912 and December 1913, in Brunshaupten on the Mecklenburg coast, where Frege frequently spent his vacations. They went for walks together and discussed philosophy over several days. Throughout this time, and especially during the war, they corresponded regularly, and some of this correspondence (from Frege to Wittgenstein) has survived, shedding light on their relationship and their different philosophical views.

While on leave from the war, Wittgenstein twice invited Frege to visit him in Vienna, but Frege never made the trip, for health reasons. On 25 March 1918 Wittgenstein wrote a letter to Frege (now lost) expressing a great debt of thanks and making him a gift of money. As his reply of 9 April shows, Frege was taken aback by this but accepted it gratefully: it helped him to buy a house in Bad Kleinen in Mecklenburg, where he lived after retiring from Jena in December 1918 (for further details, see Kreiser, 2001, pp.504–5). Wittgenstein finished a complete draft of the Tractatus during his leave in summer 1918, and Frege received a copy in early 1919. It took Frege several months to reply, and when he did, he confessed that he found it difficult to understand.

You place your propositions next to one another without justifying them or at least without justifying them in enough detail. So I often don’t know whether I should agree, since the sense is not distinct enough to me. A thorough justification would make the sense much clearer. The everyday use of language is in general too vacillating to be readily useable for difficult logical and epistemological purposes. Elucidations are necessary, it seems to me, to make the sense sharper. Right from the beginning you use rather a lot of words on whose sense much obviously depends.

(Letter from Frege, 28 June 1919)

Frege goes on to give examples of such words: “der Fall sein” (“to be the case”), “Tatsache” (“fact”), and “das Bestehen von Sachverhalten” (“the existence of states of affairs”). As he notes at one point, he struggled from the very opening propositions and found it impossible to go further.

Wittgenstein was deeply disappointed with this response. As he reported on 19 August 1919 in a letter to Russell from Cassino, where he was then in a prisoner‐of‐war camp, “[Frege] wrote to me a week ago and I gather that he doesn’t understand a word of it all. So my only hope is to see you soon and explain all to you, for it is VERY hard not to be understood by a single soul!” Wittgenstein was to be disappointed by Russell, too, but his main concern at the time was to find a publisher for his work. He approached Frege, one suggestion being the journal in which the first two essays of Frege’s “Logical Investigations” had just been published, edited by Frege’s colleague at Jena, Bruno Bauch. But as Frege made clear in a letter dated 30 September 1919, this would require rewriting the Tractatus, breaking it up into parts, each of which would focus on a single philosophical problem, with Wittgenstein’s solution to this problem presented not as bald assertions but with sufficient justification provided (Frege, 1989, p.23). This was not a suggestion likely to have gone down at all well with Wittgenstein.

Frege’s last known letter to Wittgenstein was written on 30 June 1920, responding to an earlier letter from Wittgenstein (now lost) in which he had criticized Frege’s treatment of idealism in “Der Gedanke,” a copy of which Frege had sent him. Frege also raises some further objections to the opening propositions of the Tractatus. By this time Wittgenstein had decided to become a schoolteacher, qualifying in July 1920 and taking up his first post in the small Austrian village of Trattenbach in September. So by then, it might be suggested, Wittgenstein’s thoughts were elsewhere, and he may no longer have felt any inclination to respond to Frege. However, given that he remained in correspondence with Russell, who did indeed help in getting the Tractatus published, I suspect that Frege’s reluctance to recommend publication, rooted as it was in his professed inability to get further than the opening page of the Tractatus, was the key reason why Wittgenstein broke off the correspondence.

Frege died in 1925, and Wittgenstein did not fully return to philosophy until 1929, although he met and corresponded with, among others, F.P. Ramsey during his time as a schoolteacher. Wittgenstein may have had no more contact with Frege, but he continued to read Frege’s writings. Just a month into his job in Trattenbach, he wrote to Paul Engelmann asking him to send “registered and express” the two volumes of Frege’s Grundgesetze (Engelmann, 1967, p.39). He recommended Frege to Ramsey, as is clear from a letter from Ramsey dated 11 November 1923: “I do agree that Frege is wonderful; I enjoyed his critique of the theory of irrationals in the Grundgesetze enormously.” Six weeks later Ramsey writes:

I think Frege is more read now; two great mathematicians Hilbert and Weyl have been writing on the foundations of mathematics and pay compliments to Frege, appear in fact to have appreciated him to some extent. His unpopularity would naturally go as the generation he criticized dies.

(Letter from Ramsey, 27 December 1923)

Wittgenstein continued to recommend Frege, and maintained his interest in his writings, on his return to philosophy and throughout his subsequent life. I will say something about Wittgenstein’s later engagement with Frege’s ideas in due course. Here I will end by noting Wittgenstein’s role in the first collection of Frege’s papers to be published in English, Translations from the Philosophical Writings of Gottlob Frege, edited and translated by Peter Geach and Max Black, which appeared in 1952. This included all three of Frege’s seminal essays from 1891–1892 as well as other articles and selections from both the Begriffsschrift (1879) and Grundgesetze. Wittgenstein had encouraged the project; both Geach and Black had studied with Wittgenstein at Cambridge, and Wittgenstein had advised on the selection. The book does not include excerpts from The Foundations of Arithmetic, since, as noted above, this had appeared in an English translation by J.L. Austin in 1950. Nor does it, surprisingly to us now, contain the first of the three essays of Frege’s “Logical Investigations” but, instead, the second. Here is how Geach later reported this decision:

[Wittgenstein] advised me to translate ‘Die Verneinung’, but not ‘Der Gedanke’: that, he considered, was an inferior work – it attacked idealism on its weak side, whereas a worthwhile criticism of idealism would attack it just where it was strongest. Wittgenstein told me he had made this point to Frege in correspondence: Frege could not understand – for him, idealism was the enemy he had long fought, and of course you attack your enemy on his weak side.

(Geach, in Frege, 1977, p.viii)

We catch a glimpse here not only of the dialogue that Frege and Wittgenstein actually engaged in at a crucial point in their relationship but also of one of the main, and perhaps deepest, differences in their philosophical approach.

3 Frege and Wittgenstein’s Early Work

As mentioned above, Wittgenstein’s first piece of philosophical writing appears to have been an attempt to solve Russell’s paradox that he sent to Jourdain in April 1909. We do not know what that attempted solution was, nor do we have Jourdain’s actual reply. But we do have an entry in Jourdain’s notebook that records the essence of that reply, as well as revealing that he had discussed the matter with Russell:

Russell said that the views I gave in a reply to Wittgenstein (who had ‘solved’ Russell’s contradiction) agree with his own. These views are: The difficulty seems to me to be as follows. In certain cases (e.g., Burali‐Forti’s case, Russell’s ‘class’ […], Epimenides’ remark) we get what seems to be meaningless limiting cases of statements which are not meaningless.

(Grattan‐Guinness, 1977, p.114)

If this is the view that was transmitted to Wittgenstein, then it is prescient in its anticipation of one of Wittgenstein’s central claims in the Tractatus – that (senseless) tautologies and contradictions are limiting cases of (meaningful) empirical propositions (cf. 4.46, 4.466) – as well as of what might be regarded as his central preoccupation throughout his life, that of understanding and delimiting the boundaries between meaningfulness and meaninglessness.

The ideas that Wittgenstein sent to Frege in asking if he could visit him would surely have included further thoughts on the resolution of the paradox, and it was presumably one of the main topics that they discussed on their first meeting. Frege would have been deeply interested in Wittgenstein’s thoughts. He had been devastated when Russell had informed him, in June 1902, of the contradiction in his system, which arises in the following way. In his attempt to demonstrate the logicist claim that arithmetic can be reduced to logic, Frege had defined the natural numbers as extensions of (logically definable) concepts, and had treated extensions of concepts – and hence numbers – as objects. He had also made the crucial assumption that all concepts must be defined for all objects, including extensions of concepts. Now if every concept is defined for all objects, then every concept can be thought of as dividing all objects into those that do, and those that do not, fall under it. Furthermore, if extensions of concepts are objects, then extensions themselves can be divided into those that fall under the concept whose extension they are (for example, the extension of the concept “( ) is an extension”) and those that do not (for example, the extension of the concept “( ) is a horse”). But now consider the concept “( ) is the extension of a concept under which it does not fall.” Does the extension of this concept fall under the concept or not? If it does, then it does not, and if it does not, then it does. This contradiction is one version of Russell’s paradox.

In a hastily written appendix to the second volume of the Grundgesetze, which was in press when Russell wrote to Frege informing him of the contradiction, Frege attempted to respond to the paradox. An obvious way out is to abandon the assumption that extensions of concepts are objects. But this would have been to reject one of Frege’s key claims, that numbers are objects. Frege does consider the suggestion that extensions of concepts are “improper objects,” for which only some concepts are defined, excluding those engendering the paradox. However, he rejects this on the grounds that the resulting system would be too complex, requiring “an incalculable multiplicity of types,” since it would have to be specified for every function what kind of objects are admissible as either argument or value (cf. Frege, 1997, p.282). A theory of types was what Russell was led to develop in response to the paradox; and not only did it indeed prove complex but it also generated problems of its own, not least concerning the status of the additional axioms that Russell felt obliged to introduce in seeking to demonstrate the logicist claim.

Frege’s own response was simply to outlaw concepts from applying to their own extensions. However, the resulting restriction of the axiom of his system that had given rise to the paradox has also been found to generate a contradiction, and Frege was in any case unable to provide any principled reason for outlawing this possibility (see Beaney, 2003, sec.5). As noted above, we do not know what Wittgenstein’s first “solution” to the paradox was, but it does seem that from very early on, he was skeptical of the existence of any kind of “logical object,” whether numbers, extensions of concepts, or the “logical constants” that Russell had been inclined to posit. In his first surviving letter to Russell, he remarks that the consequence of a correct account of logic “must be that there are NO logical constants” (NB 120). In the Tractatus he calls this his “fundamental thought” (“Grundgedanke”), viz., that the “logical constants” do not represent (4.0312).

This suggests a fundamental difference in philosophical attitude between Wittgenstein, on the one hand, and Frege and Russell, on the other. This difference is rooted in the claim that Wittgenstein immediately goes on to make in the letter to Russell just cited: “Logic must turn out to be a totally different kind than any other science” (NB 120). For both Frege and Russell, logic was a science just like other sciences, except for being maximally general. As a science, it was seen as having a subject matter – for Frege, logical objects and functions; for Russell, the logical constants. Wittgenstein agreed that logic was maximally general, but for just this reason, he noted in October 1913, “logic cannot treat a special set of things” (NB 98; cf. TLP 5.4). For him, what characterized logical propositions was not topic‐neutrality but vacuity.

Frege held that logic was maximally general because its laws governed all thought. The laws of logic, as laws of truth, he wrote, are “boundary stones set in an eternal foundation, which our thought can overflow but not dislodge” ([1893] 1997, p.203). This remark is made in the preface to Frege’s Grundgesetze, in a passage where Frege attacks psychologism. Wittgenstein was reportedly able to quote large parts of this preface by heart, and this passage would almost certainly have been among them. Like Frege, he rejected psychologism (cf. e.g., TLP 4.1121; on the differences between their understanding of “psychologism,” however, see Potter, 2009, pp.99–101). But unlike Frege, he did not think that treating the laws of logic as laws of truth answered the question of how logic governed our thinking. If logic is a science treating a special set of things, then how can it apply to everything? The metaphor of “boundary stones set in an eternal foundation” needs unpacking. What Wittgenstein came to believe was that logic is built into the essential nature of propositions (so thought cannot even overflow the eternal foundation that logic provides, since “illogical thought” is not, strictly speaking, thought at all). Precisely how is what he attempted to work out and explain in the Tractatus.

One argument that Wittgenstein gives for rejecting Frege’s and Russell’s view of logic is provided at the very beginning of the “Notes on Logic” that he wrote for Russell before departing for Norway in October 1913:

One reason for thinking the old notation wrong is that it is very unlikely that from every proposition p an infinite number of other propositions not‐not‐p, not‐not‐not‐not‐p, etc., should follow.

(NL 93; cf. TLP 5.43)

Wittgenstein went on to conclude from this that “not‐not‐p” must be taken as the same symbol as “p.” This in turn suggests that what might be regarded as a law of logic, namely, the principle of double negation, stating the equivalence between p and not‐not‐p, lacks content, in the way that “a = a” lacks content. In the Tractatus, after reiterating the reason just noted, he goes on to remark: “All propositions of logic, however, say the same. Namely, nothing” (5.43).

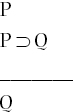

That logical propositions say nothing, in other words, lack sense, is one of the most characteristic and fundamental claims of the Tractatus, and is in direct opposition to Frege’s views. It also provided a way of articulating another objection that Wittgenstein had to Frege’s and Russell’s views, concerning their account of logical inference. The best way to explain this is to take a very simple example of a logical inference:

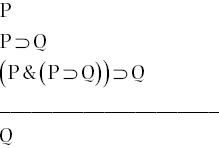

Here Q follows by modus ponens, which it is tempting to express by formulating the logical proposition “(P & (P ⊅ Q)) ⊅ Q” and saying that the inference is only valid if this proposition is true. However, we must not treat this proposition as a missing premise in the argument, which needs to be “completed” as follows:

If we do this, then an infinite regress threatens. Should we not add as a further premise “(P & (P ⊅ Q) & (P & (P ⊅ Q))) ⊅ Q”? (If the rule has to be formulated as a premise, then we generate the so‐called “paradox of inference,” first formulated – though not under that name – by Lewis Carroll in 1895.)

Unlike “P,” “P ⊅ Q,” and “Q,” all of which may have content, “(P & (P ⊅ Q)) ⊅ Q” lacks content, in the sense that it adds nothing to the inference. All it does is reflect that “Q” can indeed be inferred from “P” and “P ⊅ Q,” i.e., it reflects the rule licensing the inference. As Wittgenstein put it in notes dictated to Moore in April 1914, “Logical propositions are forms of proofs: they shew that one or more propositions follow from one (or more)” (NM 109; cf. TLP 6.1264). All logical propositions, he came to believe, are tautologies, and as such, no one set of logical propositions is more privileged than another, implying a rejection of Frege’s and Russell’s axiomatic conception of logic. (See TLP 6.1, 6.1201, 6.127, 6.1271.) They simply show that a certain inference is valid (cf. TLP 6.1264).

Wittgenstein’s notes to Moore open with the remark: “Logical so‐called propositions shew [the] logical properties of language and therefore of [the] Universe, but say nothing” (NM 108; cf. TLP 6.12). This distinction between saying and showing is another fundamental idea of the Tractatus, but it does not appear in the notes he wrote for Russell in October 1913. Wittgenstein went to Norway immediately after writing these notes to Russell and stayed there until July 1914, with the exception of several weeks over Christmas, when he went home to Vienna via a visit to Frege in Mecklenburg. (Moore visited Wittgenstein in Norway in March, and Wittgenstein dictated the notes to him during the first two weeks of April.) There is nothing in the letters that Wittgenstein wrote during this period to shed any light on exactly when Wittgenstein came to draw the distinction, but an obvious suggestion is that it had something to do with his discussions with Frege.

In an influential paper published in 1976, Peter Geach suggested that Wittgenstein’s distinction between saying and showing was already foreshadowed in Frege’s philosophy, and indeed can be invoked in making sense of (if not actually resolving) a problem in Frege’s philosophy. This is the problem that has come to be known as the paradox of the concept “horse.” According to Frege, there is an absolute distinction between objects and concepts (or functions, more generally): the former are “saturated,” reflecting the fact that the names for them are “complete,” and the latter are “unsaturated,” reflecting the fact that the names for them are “incomplete.” In “Pegasus is a horse,” for example, “Pegasus” is a proper name, referring to an object, while “( ) is a horse” is a concept‐word, with the gap indicating where the name goes to complete the expression to form a sentence. But now consider the sentence “The concept horse is a concept,” which might seem obviously true. On Frege’s view, however, the use of the definite article in “the concept horse” indicates an object (if anything), not a concept, so that, strictly speaking, the sentence is false. As Frege wrote in “On Concept and Object,” in discussing the problem, “By a kind of necessity of language, my expressions, taken literally, sometimes miss my thought; I mention an object, when what I intend is a concept” ([1892b] 1997, p.192). He found no way round the problem, which he thought was “founded on the nature of our language,” and he therefore concluded “that we cannot avoid a certain inappropriateness of linguistic expression; and that there is nothing for it but to realize this and always take it into account” ([1892b] 1997, p.193).

If I had to select a single remark or idea that demonstrated the profound effect that Frege had on Wittgenstein, then it would be this. (It is no accident that it is this idea that has inspired so‐called “New Wittgenstein” readings of the Tractatus, from the work of Cora Diamond onwards; see especially Diamond, 1988.) We see revealed here the central theme that came to obsess Wittgenstein: the way that language can mislead us, especially when doing philosophy, which easily gives rise to the temptation to utter nonsense. Armed with Wittgenstein’s distinction between saying and showing, however, we can at least offer a formulation of what Frege wants to convey: namely, that what the sentence “The concept horse is a concept” tries to say can only be shown – shown, that is, by using the concept‐word “( ) is a horse” to say, truly or falsely, that an object is a horse. (It is but a short step from here to Wittgenstein’s later conception of meaning as use: the meaning of “( ) is a horse,” for example, is not given by specifying some entity (whether object or function) but is simply revealed by its use.)

The distinction between objects and concepts (functions) is the most fundamental distinction in Frege’s philosophy, and yet this distinction cannot actually be stated in Frege’s “Begriffsschrift” (literally, “concept‐script”), as he called his logical language, which had been specifically designed to capture all legitimate thoughts. Any attempt to formalize “No concepts are objects” would require quantifying over entities of which it could be meaningfully asserted either that they are concepts or that they are objects. But there are no such entities, on Frege’s view. (As Wittgenstein was to put it, the concept of an object and the concept of a concept are “formal concepts”; TLP 4.126 ff. For discussion of this, see McGinn 2006, ch.7.) Here, too, though, we might suggest that what Frege is trying to say in uttering a sentence such as “No concepts are objects” can only be shown in the correct use of his logical language. The idea here generalizes. Any attempt to express the distinctions upon which the logical language itself depends cannot be expressed within that language. If we now recognize that, in his early work, Wittgenstein understood by “logic” precisely the logic that Frege saw himself as formalizing in his Begriffsschrift (not that Wittgenstein thought that Frege had got his notation right; see e.g., TLP 3.325, 4.442, 5.42, 5.53 ff.), then we arrive at the result that everything that we might try to say about the conditions of the applicability of this logic cannot actually be said but only shown. In the light of all this, it is perhaps not surprising that Wittgenstein himself was eventually forced to admit that his own attempts in the Tractatus to elucidate these conditions resulted in nonsense that had to be “overcome” at the end.

We do not know whether Frege and Wittgenstein discussed the paradox of the concept “horse” when they met in December 1913. But we do know from what Wittgenstein wrote to Russell immediately after his discussions with Frege the previous year, i.e., in December 1912, that Wittgenstein had come to appreciate the basic idea of Frege’s distinction between object and concept. At this point Wittgenstein was clearly under the spell of Russell’s conception of a proposition as some kind of complex entity composed of simpler entities. But this raised the question of the unity of such a proposition. If the only constituents of a proposition are objects, then how do they combine to generate a meaningful proposition? As Wittgenstein was to put it, what makes “Socrates is mortal” meaningful but “mortality is Socrates” meaningless? Frege’s answer was clear: concepts are “unsaturated,” reflected in the fact that the concept‐word, as properly represented in this example by “( ) is mortal,” contains a “gap” indicating where the proper name goes to complete the sentence.

Wittgenstein seems to have recognized what is in effect Frege’s solution to the problem of the unity of the proposition. On 26 December 1912 he wrote to Russell: “I had a long discussion with Frege about our theory of symbolism of which, I think, he roughly understood the general outline. […] The complex‐problem is now clearer to me and I hope very much that I may solve it” (NB 121). On 16 January 1913, he then writes to Russell:

I have changed my views on “atomic” complexes: I now think that qualities, relations (like love) etc. are all copulae! That means I for instance analyse a subject‐predicate proposition, say, “Socrates is human” into “Socrates” and “something is human”, (which I think is not complex). The reason for this is a very fundamental one. I think that there cannot be different Types of things! In other words whatever can be symbolized by a simple proper name must belong to one type. And further: every theory of types must be rendered superfluous by a proper theory of symbolism: For instance if I analyse the proposition Socrates is mortal into Socrates, mortality and (∃x,y) ∈I (x,y) I want a theory of types to tell me that “mortality is Socrates” is nonsensical, because if I treat “mortality” as a proper name (as I did) there is nothing to prevent me to make the substitution the wrong way round. But if I analyse (as I do now) into Socrates and (∃x).x is mortal or generally into x and (∃x) ϕx it becomes impossible to substitute the wrong way round because the two symbols are now of a different kind themselves. What I am most certain of is not however the correctness of my present way of analysis, but of the fact that all theory of types must be done away with by a theory of symbolism showing that what seem to be different kinds of things are symbolized by different kinds of symbols which cannot possibly be substituted in one another’s places. I hope I have made this fairly clear!

(NB 16.1.13)

Wittgenstein’s “analysis” here differs from Frege’s, and he did indeed soon come to reject it, but the essential idea that there are different “kinds” of things that can only be shown by a correct symbolism remained. The distinction between saying and showing is not formulated explicitly until April 1914, in the notes he dictated to Moore, but it is clearly implicit in this letter. It provides a good example of an idea that was inspired by Wittgenstein’s dialogue with Frege, which he used both in articulating his objections to the views of Frege and Russell and in attempting to resolve the problems raised by their work.

Most of Wittgenstein’s objections to Frege’s and Russell’s views are already made in his “Notes on Logic” of 1913 (for a full discussion, see Potter, 2009). He attempts to resolve the problems raised by their work in the years that follow, developing a positive account of logic and language rooted in his so‐called picture theory of the proposition. The idea of treating propositions as “pictures” first emerged in September 1914 (NB 7), and his positive account found its definitive articulation in the Tractatus (see Beaney, 2006; McGinn, 2006, chs1–5; Diamond, 2013). As far as Frege is concerned, he is mentioned by name in 17 of the numbered propositions of the Tractatus (for further discussion, see Kienzler, 2011). He cites Frege favorably in four of these propositions (3.318, 3.325, 4.431, 5.451), although with some qualification in two of them (3.325, 4.431). In most of them, however, he criticizes Frege. Some of these criticisms have already been mentioned: his repudiation of Frege’s conceptions of logic (6.1271), logical inference (5.132), and logical objects (5.4, 5.42). Space prohibits discussion of the other criticisms, but for the record they can be noted here. Wittgenstein also raises objections to Frege’s views on sense (Sinn) and reference (Bedeutung), and especially his treatment of propositions as names of truth values (3.143, 4.063, 5.02, 5.4733, 6.232), and he criticizes Frege’s introduction of an assertion‐sign into logic (4.442; cf. BT 160–1; PI §22) and his conception of generality, where he takes issue with Frege for failing to appreciate the role of “formal concepts” (4.1272, 4.1273, 5.521; cf. BT 247–8). (See the end of this chapter for suggested further reading on these topics.)

4 Frege and Wittgenstein’s Later Work

The Tractatus was essentially complete in 1918. In that same year Frege published “Der Gedanke” (“Thought”), the first of his “Logical Investigations,” and sent a copy to Wittgenstein. The second essay, “Die Verneinung” (“Negation”), was published in 1919 and “Gedankengefüge” (“Compound Thoughts”) followed in 1923. None of these influenced the Tractatus directly, although ideas that Frege expressed in these works may have been discussed in Frege’s earlier conversations with Wittgenstein. But their influence can certainly be traced in Wittgenstein’s later work, and Wittgenstein re‐engaged with Frege’s thinking on his return to philosophy in 1929.

As mentioned above, Frege and Wittgenstein corresponded during and immediately after World War I, and the letters from Frege to Wittgenstein in 1919 and 1920, in which Frege comments on the draft of the Tractatus that had been sent to him and responds to Wittgenstein’s own comments on “Der Gedanke,” are especially revealing. I will note just two issues here, one raised by Frege’s comments on the Tractatus and the other by Wittgenstein’s comments on “Der Gedanke.” The first issue concerns the opening propositions of the Tractatus. In 1.1 Wittgenstein states that “The world is the totality of facts, not of things.” A few propositions later he claims both that a fact (Tatsache) is the obtaining of states of affairs (das Bestehen von Sachverhalten) and that a state of affairs is a combination of objects (2, 2.01). This would seem to imply that objects are constituents of facts, so that the world, after all, is a totality of things and not just of facts; and it is this implication that Frege draws out and criticizes in the letter he wrote to Wittgenstein on 28 June 1919 (Frege, 1989, pp.19–20). On Frege’s own view, “facts” are simply true thoughts, and the constituents of thoughts are the senses of the expressions that constitute the sentences that express the thoughts; the constituents of thoughts are not the references (Bedeutungen) of those expressions.

We do not have Wittgenstein’s reply to this, although one might argue that, properly interpreted, facts are not identified with (existing) states of affairs; it is that a state of affairs obtains that is the fact. (On the difficulties in interpreting Wittgenstein here, see the entry under “fact” in Glock, 1996.) In remarks on “Complex and Fact” written in June 1931, however, Wittgenstein says the following:

To say that a red circle is composed of redness and circularity, or is a complex with these component parts, is a misuse of these words and is misleading. (Frege was aware of this and told me.)

It is just as misleading to say the fact that this circle is red (that I am tired) is a complex whose component parts are a circle and redness (myself and tiredness). (PR 302)

Wittgenstein does not indicate whether he took himself to have failed to distinguish adequately between fact and complex in the Tractatus; but it is clear that he now recognizes how important this distinction is, parenthetically suggesting that it was Frege who taught him this.

The second issue concerns Wittgenstein’s comments on Frege’s treatment of idealism in “Der Gedanke.” As reported above, Wittgenstein thought that Frege had attacked idealism on its weak side, whereas the most effective critique needed to uncover its deepest, strongest roots. Wittgenstein must have raised this objection in a letter (now lost) to Frege himself, as on 3 April 1920 Frege wrote back to him:

Many thanks for your letter of 19 March! Of course I don’t mind your frankness. But I would very much like to know what deep grounds of idealism you think I have not grasped. I understood that you yourself do not take epistemological idealism to be true. You thus recognize, I think, that there are no deeper grounds at all for this idealism. The grounds for it can then only be apparent grounds, not logical grounds. One is indeed misled at times by language, since language does not always satisfy logical demands. In the formation of language, as well as the logical abilities of human beings, much that is psychological has had an effect. Logical errors do not originate from logic, but arise from the contaminations or disruptions to which the logical activity of human beings is exposed. It was not my intention to track down all such disruptions of psychological‐linguistic origin. Please just go through my essay on thought until you come to the first sentence with which you disagree and let me know which this is and the reasons for your disagreement. This may well be the best way for me to see what you have in mind. I might not have wanted to combat idealism at all in the sense you meant. I may well not have used the expression ‘idealism’ at all. Take my sentences just as they are, without imputing an intention that might have been foreign to me.

(Letter from Frege, 3 April 1920)

We do not have Wittgenstein’s reply, nor do we have any subsequent letters from Frege. But Frege was right that he does not use the term “idealism” in his essay; and it is equally clear that Wittgenstein thought he saw a deep truth in idealism – or at least in solipsism – that he attempted to articulate in the notoriously difficult sections of the Tractatus that discuss “the limits of my language” (5.6–5.641). What Wittgenstein presumably had in mind in criticizing Frege, though, was the passage in “Der Gedanke” where Frege discusses the thesis that only what is my idea can be the object of my awareness ([1918] 1997, pp.337–41). Frege argues that since ideas require an owner, my ideas must have an owner, which must then be recognized as an object of my awareness that is not itself an idea. This frees the way, he suggests, for acknowledging other people as independent owners of ideas, which in turn makes the probability “very great, so great that it is in my opinion no longer distinguishable from certainty” that such people, and hence an external world, exist ([1918] 1997, p.341). This argument from “probability” is presumably what Wittgenstein was alluding to in his talk of Frege’s attacking idealism on its weak side. A far more effective attack is to identify a fundamental assumption on which one might well be tempted to agree (like Frege) with the idealist and show how that assumption needs repudiating or qualifying (e.g., by reinterpreting or disambiguating) in order to resist the idealist’s conclusion.

Just such an assumption is Frege’s claim in “Der Gedanke” that “Nobody else has my idea,” which might seem to be as incontrovertible as “Nobody else has my pain,” which Frege also asserts ([1918] 1997, p.335). But this is precisely the assertion that Wittgenstein interrogates in §253 of his later Philosophical Investigations, as part of his so‐called private language argument. (For further discussion of one source of the private language argument lying in Wittgenstein’s reading of “Der Gedanke,” see Künne, 2009, pp.36–40.) This later argument, we might say, does indeed attack idealism on its strong side. Frege’s and Wittgenstein’s approaches to idealism thus reveal very different philosophical methodologies. Frege criticizes a doctrine by taking its formulation literally (as he urges Wittgenstein to do of his own sentences in the letter just cited) and drawing out its consequences in an attempt to refute it by reductio ad absurdum. Wittgenstein’s approach, by contrast, seeks to identify the underlying assumption that might be accepted on both sides of a dispute in order to show how the dispute itself is fundamentally misguided.

In this respect §308 of the Investigations is particularly revealing of Wittgenstein’s methodology. Wittgenstein here talks about the “first step” in a philosophical dispute being “the one that altogether escapes notice” and “that’s just what commits us to a particular way of looking at the matter,” adding in parentheses: “The decisive movement in the conjuring trick has been made, and it was the very one that seemed to us quite innocent.” Frege’s work, I would say, provides excellent examples of precisely the kind of “first steps” or “decisive movements” that generate the philosophical disputes that Wittgenstein aimed to dissolve; and this is one of the main reasons why Wittgenstein found in Frege’s writings a continual source of inspiration. It is significant that it is after this passage that Wittgenstein makes his famous remark about the aim of philosophy being to show the fly the way out of the fly‐bottle (PI §309).

In his early thinking, Wittgenstein had himself been trapped in a fly‐bottle of Frege’s making. As noted above, he had accepted Frege’s view that logic is essentially what Frege had attempted to formalize in his Begriffsschrift. For Frege, this was rooted in his use of function–argument analysis and his consequent emphasis on the distinction between concept and object. Frege’s assumption that concepts are functions was a “first step” that did indeed commit him to a particular way of looking at things. (I discuss how Frege’s use of function–argument analysis led to all his characteristic doctrines in Beaney, 2007; 2011.) In his later critique of Fregean logic, the concept/object distinction was one of the first doctrines that Wittgenstein attacked. In the Philosophical Remarks, for example, Wittgenstein treats this distinction as just a version of the subject/predicate distinction, which reflects not just one logical form but “countless fundamentally different logical forms” (PR 119). Such forms, he writes, are norms of representation, “moulds into which we have squeezed the proposition” (PR 137).

One feature of Frege’s way of looking at things was his assumption that concepts are – or should be – sharp, in other words, that it must be determined for any (genuine) concept whether any given object falls under it or not (see e.g., Frege, [1903] 1997, p.259). This, too, was something that Wittgenstein later criticized. In §71 of the Investigations, for example, where Frege is explicitly mentioned, his imagined interlocutor asks “But is a blurred concept a concept at all?,” and Wittgenstein goes on to reply that a blurred concept such as that of a game may actually have advantages over sharper concepts (cf. BT 68–9). Wittgenstein writes:

We want to say that there can’t be any vagueness in logic. The idea now absorbs us that the ideal ‘must’ occur in reality.

(PI §101)

The ideal, as we conceive it, is unshakable. You can’t step outside it. […] The idea is like a pair of glasses on our nose through which we see whatever we look at. It never occurs to us to take them off.

(PI §103)

These remarks can be seen as addressed to Frege just as much as to his own earlier self. (On Wittgenstein’s account of vagueness, see also Chapter 25, VAGUENESS AND FAMILY RESEMBLANCE.)

Wittgenstein also had Frege in mind in his discussion of rule‐following, which is central to both Philosophical Investigations and Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics. Frege, he thought, was someone who held the view that he was concerned to criticize – that the applications of a rule are already somehow predetermined, in the way that a line between two points is already there before it has been drawn or a series of numbers is already there once the rule has been given (see e.g., RFM I §21; BT 343, 570). Especially in the Philosophical Investigations, Frege’s name may rarely be mentioned, but his ideas are certainly among the targets in many of Wittgenstein’s discussions.

5 Conclusion

I have concentrated in the previous two sections on Wittgenstein’s criticisms of Frege’s ideas, suggesting that Wittgenstein came to see in Frege’s philosophy a source of “first steps” that he sought to identify in order to dissolve philosophical disputes. But there are also ideas and attitudes that Wittgenstein endorsed. Wittgenstein shared Frege’s anti‐psychologism and admired his critique of formalism, for example. (Anti‐psychologism permeates Wittgenstein’s work, but for particularly clear statements, see e.g., TLP 4.1121; BB 6; PPF §xiv. For Wittgenstein’s attitude to Frege’s critique of formalism, see e.g., BB 4; BT 3.) But where he does endorse aspects of Frege’s philosophy, he nearly always does so in a qualified form. In the Tractatus, for example, he writes: “Only the proposition has sense [Sinn]; only in the context of a proposition has a name reference [Bedeutung]” (3.3). Although Frege is not mentioned by name, this is a clear reference to Frege’s famous context principle. But Frege formulated this principle at a time (1884) when he had not yet distinguished between sense and reference, and once he had done so, this complicated issues sufficiently for him to quietly drop the principle. For the early Wittgenstein, propositions have sense but not reference, and names have reference but not sense. So the context principle means something different for Wittgenstein than it did for Frege.

In §49 of the Investigations, Wittgenstein again endorses the context principle, in arguing that mere naming is not yet to make a move in a language‐game. He then explicitly mentions Frege in claiming that “This is what Frege meant too when he said that a word has a meaning only in the context of a sentence.” Given the different context in which Frege formulated this principle, this is highly contentious; but it is significant that Wittgenstein should want to endorse Frege on this point. The context principle was clearly influential. Indeed, one might argue that Wittgenstein generalized the principle in his later philosophy: only in the context of a language‐game – or more broadly still, in the context of a “form of life” – does a linguistic expression have a meaning. The context principle thus provides a further example of how exploring the relationship between Frege and Wittgenstein takes us to the heart of both philosophers’ work. Seeing how Wittgenstein criticized and transformed Frege’s ideas also sheds light on some of the deepest issues in analytic philosophy.

Let us leave the last word with Frege, in a letter to Wittgenstein that he wrote on 16 September 1919:

In long conversations with you I have come to know a man who, like me, has searched for the truth, partly along different paths. But it is precisely this that allows me to hope to find something in you that can complete, perhaps even correct, what was found by me.

References

Translations from Wittgenstein’s Tractatus and Frege’s letters to Wittgenstein are my own.

- Beaney, M. (2003). Russell and Frege. In N. Griffin (Ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Bertrand Russell (pp.128–170). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Beaney, M. (2006). Wittgenstein on Language: From Simples to Samples. In E. Lepore and B. Smith (Eds). The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Language (pp.40–59). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Beaney, M. (2007). Frege’s Use of Function‐Argument Analysis and his Introduction of Truth‐values as Objects. Grazer Philosophische Studien, 75, 93–123.

- Beaney, M. (2011). Frege. In B. Lee (Ed.). Key Thinkers: Philosophy of Language (pp.33–55). London: Continuum.

- Carroll, L. (1895). What the Tortoise said to Achilles. Mind, 4, 278–280.

- Diamond, C. (1988). Throwing away the Ladder: How to Read the Tractatus. Philosophy, 63, 5–27.

- Diamond, C. (2013). Reading the Tractatus with G.E.M. Anscombe. In M. Beaney (Ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Analytic Philosophy (pp.870–905). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Engelmann, P. (1967). Letters from Wittgenstein, with a Memoir. Ed. B.F. McGuinness. Trans. L. Furtmüller. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Frege, G. (1879). Begriffsschrift. [Concept‐script.] Halle: L. Nebert.

- Frege, G. ([1884] 1950). The Foundations of Arithmetic. Trans. J.L. Austin. Oxford: Blackwell. (Original work published 1884.)

- Frege, G. ([1891] 1997). Function and Concept. Translation in G. Frege. (1997). The Frege Reader (pp.130–148). Ed. M. Beaney. Oxford: Blackwell. (Original work published 1891.)

- Frege, G. ([1892a] 1997). On Sinn and Bedeutung. Translation in G. Frege. (1997). The Frege Reader (pp.151–171). Ed. M. Beaney. Oxford: Blackwell. (Original work published 1892.)

- Frege, G. ([1892b] 1997). On Concept and Object. Translation in G. Frege. (1997). The Frege Reader (pp.181–193). Ed. M. Beaney. Oxford: Blackwell. (Original work published.)

- Frege, G. ([1893] 1997). Grundgesetze der Arithmetik (Vol. 1). Translation of selections in G. Frege. (1997). The Frege Reader (pp.194–223). Ed. M. Beaney. Oxford: Blackwell. (Original work published 1893.)

- Frege, G. ([1903] 1997). Grundgesetze der Arithmetik (Vol. 2). Translation of selections in G. Frege. (1997). The Frege Reader (pp.258–289). Ed. M. Beaney. Oxford: Blackwell. (Original work published 1903.)

- Frege, G. ([1918] 1997). Der Gedanke. Eine logische Untersuchung. Translation in G. Frege. (1997). The Frege Reader (pp.325–345). Ed. M. Beaney. Oxford: Blackwell. (Original work published 1918.)

- Frege, G. ([1919] 1997). Die Verneinung. Eine logische Untersuchung. Translation in G. Frege. (1997). The Frege Reader (pp.345–361). Ed. M. Beaney. Oxford: Blackwell. (Original work published 1919.)

- Frege, G. (1923). Logische Untersuchungen. Dritter Teil: Gedankengefüge. [Logical Investigations: Third Part: Compound Thoughts.] Beiträge zur Philosophie des deutschen Idealismus, 3, 36–51; trans. in G. Frege. (1977). Logical Investigations (pp.55–78). Ed. P.T. Geach, trans. P.T. Geach and R.H. Stoothoff. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Frege, G. (1952). Translations from the Philosophical Writings of Gottlob Frege. Ed. and trans. P.T. Geach and M. Black. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Frege, G. (1977). Logical Investigations. Ed. P.T. Geach, trans. P.T. Geach and R.H. Stoothoff. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Frege, G. (1989). Briefe an Ludwig Wittgenstein. [Letters to Ludwig Wittgenstein.] Ed. A. Janik. In B. McGuinness and R. Haller (Eds). Wittgenstein in Focus/Im Brennpunkt: Wittgenstein (pp.5–33). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Frege, G. (1997). The Frege Reader. Ed. M. Beaney. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Geach, P.T. (1961). Frege. In G.E.M. Anscombe and P.T. Geach. Three Philosophers (pp.129–162). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Geach, P.T. (1976). Saying and Showing in Frege and Wittgenstein. Acta Philosophica Fennica, 28, 54–70.

- Glock, H.‐J. (1996). A Wittgenstein Dictionary. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Grattan‐Guinness, I. (1977). Dear Russell, Dear Jourdain: A Commentary on Russell's Logic, Based on his Correspondence with Philip Jourdain. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Kienzler, W. (2011). Wittgenstein and Frege. In O. Kuusela and M. McGinn (Eds). The Oxford Handbook of Wittgenstein (pp.79–104). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kreiser, L. (2001). Gottlob Frege: Leben – Werk – Zeit. [Gottlob Frege: Life, Work, Times.] Hamburg: Felix Meiner.

- Künne, W. (2009). Wittgenstein and Frege’s Logical Investigations. In H.‐J. Glock and J. Hyman (Eds). Wittgenstein and Analytic Philosophy: Essays for P.M.S. Hacker (pp.26–62). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McGinn, M. (2006). Elucidating the Tractatus: Wittgenstein’s Early Philosophy of Logic and Language. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Monk, R. (1990). Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Potter, M. (2009). Wittgenstein’s Notes on Logic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Reck, E.H. (2002). Wittgenstein’s “Great Debt” to Frege: Biographical Traces and Philosophical Themes. In E.H. Reck (Ed.). From Frege to Wittgenstein: Perspectives on Early Analytic Philosophy (pp.3–38). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Russell, B. (1903). The Principles of Mathematics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Further Reading

For further discussion of the relationship between Frege and Wittgenstein (some of which has been cited above), see:

- Baker, G.P. (1988). Wittgenstein, Frege and the Vienna Circle. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Beaney, M. (2012). Logic and Metaphysics in Early Analytic Philosophy. In L. Haaparanta and H. Koskinen (Eds). Categories of Being: Essays on Metaphysics and Logic (pp.257–292). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Conant, J. (2002). The Method of the Tractatus. In E.H. Reck (Ed.). From Frege to Wittgenstein: Perspectives on Early Analytic Philosophy (pp.374–462). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Diamond, C. (2010). Inheriting from Frege: The Work of Reception, as Wittgenstein Did It. In M. Potter and T. Ricketts (Eds). The Cambridge Companion to Frege (pp.550–601). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Diamond, C. (2013). Reading the Tractatus with G.E.M. Anscombe. In M. Beaney (Ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Analytic Philosophy (pp.870–905). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dummett, M.A.E. (1981). Frege and Wittgenstein. In I. Block (Ed.). Perspectives on the Philosophy of Wittgenstein (pp. 31–42). Oxford: Blackwell. Reprinted inM.A.E. Dummett (1991). Frege and Other Philosophers (pp.237–248). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Floyd, J. (2011). The Frege–Wittgenstein Correspondence: Interpretive Themes. In E. de Pellegrin (Ed.). Interactive Wittgenstein: Essays in Memory of Georg Henrik von Wright (pp.75–107). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Geach, P.T. (1976). Saying and Showing in Frege and Wittgenstein. In J. Hintikka (Ed.). Essays on Wittgenstein in Honour of G.H. von Wright (pp. 54–70). Acta Philosophica Fennica, 28, Amsterdam.

- Goldfarb, W. (2002). Wittgenstein’s Understanding of Frege: The Pre‐Tractarian Evidence. In E.H. Reck (Ed). From Frege to Wittgenstein: Perspectives on Early Analytic Philosophy (pp.185–200). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hacker, P.M.S. (1986). Insight and Illusion: Themes in the Philosophy of Wittgenstein. Oxford: Clarendon, ch.2.

- Hacker, P.M.S. (2001a). Frege and the Early Wittgenstein. In P.M.S. Hacker, Wittgenstein: Connections and Controversies (pp.191–218). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hacker, P.M.S. (2001b). Frege and the Later Wittgenstein. In P.M.S. Hacker, Wittgenstein: Connections and Controversies (pp.219–241). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Kienzler, W. (2011). Wittgenstein and Frege. In O. Kuusela and M. McGinn (Eds). The Oxford Handbook of Wittgenstein (pp. 79–104). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Künne, W. (2009). Wittgenstein and Frege’s Logical Investigations. In H.‐J. Glock and J. Hyman (Eds). Wittgenstein and Analytic Philosophy (pp. 26–62). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McGinn, M. (2006). Elucidating the Tractatus. Oxford: Clarendon Press, chs 2–3.

- Potter, M. (2009). Wittgenstein’s Notes on Logic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Reck, E.H. (1997). Frege’s Influence on Wittgenstein: Reversing Metaphysics via the Context Principle. In W.W. Tait (Ed.). Early Analytic Philosophy: Frege, Russell, Wittgenstein (pp. 123–185). Chicago: Open Court.

- Reck, E.H. (2002). Wittgenstein’s “Great Debt” to Frege: Biographical Traces and Philosophical Themes. In E.H. Reck (Ed). From Frege to Wittgenstein: Perspectives on Early Analytic Philosophy (pp.3–38). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ricketts, T. (2002). Wittgenstein against Frege and Russell. In E.H. Reck (Ed). From Frege to Wittgenstein: Perspectives on Early Analytic Philosophy (pp.227–251). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Travis, C. (2006). Thought’s Footing: A Theme in Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

More specifically, on Wittgenstein’s objections to Frege’s treatment of propositions as names of truth values, see:

- Diamond, C. (2010). Inheriting from Frege: The Work of Reception, as Wittgenstein Did It. In M. Potter and T. Ricketts (Eds). The Cambridge Companion to Frege (pp.550–601). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, secs 4–7.

- Goldfarb, W. (2002). Wittgenstein’s Understanding of Frege: The Pre‐Tractarian Evidence. In E.H. Reck (Ed). From Frege to Wittgenstein: Perspectives on Early Analytic Philosophy (pp.185–200). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ricketts, T. (2002). Wittgenstein against Frege and Russell. In E.H. Reck (Ed). From Frege to Wittgenstein: Perspectives on Early Analytic Philosophy (pp.227–251). New York: Oxford University Press, sec. 4.

On Wittgenstein’s criticism of Frege’s introduction of an assertion‐sign into logic, see:

- Künne, W. (2009). Wittgenstein and Frege’s Logical Investigations. In H.‐J. Glock and J. Hyman (Eds). Wittgenstein and Analytic Philosophy (pp. 26–62). Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.54–57.

- Potter, M. (2009). Wittgenstein’s Notes on Logic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ch.10.

On Wittgenstein’s repudiation of Frege’s conception of generality and his related claim that Frege fails to appreciate the role of “formal concepts,” see:

- Fogelin, R.J. (1987). Wittgenstein, 2nd edn. London: Routledge, ch.5.

- McGinn, M. (2006). Elucidating the Tractatus. Oxford: Clarendon Press, ch.7.

On “New Wittgenstein” readings of the Tractatus, which take seriously Frege’s influence on Wittgenstein, see especially the papers collected in:

- Crary, A. and Read, R. (Eds) (2000). The New Wittgenstein. London: Routledge.

For a recent account, see:

- Kremer, M. (2013). The Whole Meaning of a Book of Nonsense: Reading Wittgenstein’s Tractatus. In M. Beaney (Ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Analytic Philosophy (pp.451–485). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

For discussion of Wittgenstein’s anti‐psychologism, see:

- Travis, C. (2006a). Thought’s Footing: A Theme in Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ch.1.

- Travis, C. (2006b). Psychologism. In E. Lepore and B. Smith (Eds). The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Language (pp.103–126). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Finally, on the controversial question of Frege’s later adherence to the context principle, see:

- Beaney, M. (1996). Frege: Making Sense, London: Duckworth, §8.2.

- Ricketts, T. (2010). Concepts, Objects and the Context Principle. In M. Potter and T. Ricketts (Eds). The Cambridge Companion to Frege. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.149–219.

and on the role of the context principle in the work of both Frege and Wittgenstein, see:

- Reck, E.H. (1997). Frege’s Influence on Wittgenstein: Reversing Metaphysics via the Context Principle. In W.W. Tait (Ed.). Early Analytic Philosophy: Frege, Russell, Wittgenstein (pp. 123–185). Chicago: Open Court.