Nothing is more damaging to a new truth than an old error.

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Today’s new truth is that millennials are indeed bringing positive changes to the workplace and society at large. Unfortunately, over the last decade, errors have been made in shaping the perception of this generation. As a result, the biggest danger facing the millennial generation and their potential for success is what today’s dominant population, boomers and Xers, think of them.

As an example, consider an experience I had after leading a powerful panel discussion about millennials. Many audience members of older generations shared how much my message resonated with them and how they felt a new sense of clarity about millennials. However, a corporate vice president in the audience pulled me aside and said, “But really, Crystal, at the end of the day, all millennials want is money, just like everyone else. Especially when they grow up.” Having just explored my own story of pursuing potential during the panel, as well as the unconventional stories of five other millennials on stage (who were all grown ups!), I was a bit taken aback. I asked, “Sir, have you talked to many millennials?” He responded, “My kids are millennials and yeah they want the new car, the new clothes, and the mansion.” I thought for a moment before responding, “Well, sir, those are the kids you raised. Those aren’t all the kids out there. There might even be more to your own kids than you realize.”

He laughed in response and I smiled, but the conversation clearly gave him something to think about. He had bought into the stereotypical perception of the millennial generation. Consider the lens this vice president was wearing every time he looked at members of the youngest generation. How many excuses and explanations did he make to justify the exceptions he encountered among the millennial generation? How often did he refuse to make a change to create modern culture in the workplace because he felt he would be pandering to the younger generation?

In comparison, a boomer I work closely with has had a lifelong philosophy to always stay connected to “the new,” the latest changes going on. One way she does this is by making sure to work with younger people. After a successful career in research and development and later training, she has retired and yet, she purposefully pursues keeping fresh. Our relationship is one where I learn from her and she learns from me, an interdependent and most importantly (in her words) fun relationship. She is one to experiment with and embrace new approaches. How has having this lens created opportunities for her that would otherwise have been absent? What does her ability to build relationships across generations look like? How does looking beyond the biases represented in media help her create an objective, strategic approach?

Many leaders stubbornly cling to an “it’s always been done this way” mentality and, even if they want to, have limited tools to discover what modernizing means because media paints millennials as impossible overgrown children who have now joined the workplace. The tools are limited to what works at organizations thought of as sexy by millennials: Google, Amazon, Facebook, start-ups. Often, these tools simply don’t make sense for other industries. As a result, the millennial generation is seen as an enormous challenge, something to be managed, to be taught, to be contended with, and ultimately, to be integrated into how we have always done things. Yet there are two sides to every story.

What do these negative perceptions sound like? Consider the following phrases, questions, and comments I often come across in my interactions with corporate leaders, including HR:

› They are lazy, entitled job-hoppers.

› Why do we have to pander to millennials?

› They need to be babied and hand-held.

› They want to be handed everything without putting in the work.

› We’ve given them more than we had and they still aren’t satisfied.

› They think they can just walk into a room with the CEO and gain an audience.

› They don’t have a sense of decorum.

› The millennials are the same as everyone else. They want what everyone wants.

› One day, they will have to grow up and be driven by money and the same things that everyone always has been concerned with.

These are the prevailing perceptions, spoken or unspoken, every time a young person is invited to interview, every time a new hire starts, and every time a young colleague is promoted to a management position. As Eric Hoover wrote in the Chronicle of Higher Education, “Such descriptions are reminders that most renderings of millennials are done by older people, looking through the windows of their own experiences.”1 These perceptions are wrong and fundamentally damaging to employee engagement, workplace productivity, and positive culture-building.

It’s not enough to know the business impacts of these negative perceptions. To create a blank page for understanding millennials, we need to address the elephant in the room up front with two key arguments against today’s top prevailing negative perceptions: that millennials are lazy, entitled, job-hopping, need to be hand-held, and have issues with authority.

“When I was young, I had to walk four miles in the snow, barefoot, uphill both ways. Kids these days have it too easy.” This cliché captures an important truth: every generation has complained about the generations that followed. In reality, every generation has been lazier and more entitled compared to the previous generation’s idea of hard work because every generation’s goal is to make life easier for the next generation.

Boomers may have had to share a room with another sibling or wait in line to use the house’s single corded phone. In comparison, a member of the traditionalist generation may have had to share a room with their whole family or wait for a telegram to hear from a loved one. Sure, in today’s generation most everyone has their own cell phone and the majority can afford housing with separate rooms for each child. But that doesn’t mean millennials are any more entitled or lazy than boomers were perceived to be by traditionalists.

Everyone has benefited from innovations such as access to better health care, public utilities, and transportation. Everyone has benefited from technology and as a result, we all have become lazier and more entitled. Especially in first world countries, regardless of age or generation, people expect to have access to clean water, food, transportation, education, and jobs. We have reached a level of comfort such that not only are our basic needs met, but our self-actualization needs are met as well. These are all luxuries that most previous generations did not have. To blame the millennial generation for enjoying the fruits of humanity’s progress since childhood is a behavior borne out of misdirected bitterness and envy—vices that serve to encumber decision making instead of empowering it.

Also, as in every other generation, just because society has made life better for people doesn’t mean that new challenges haven’t arisen in their place. Yes, we are instantly connected today to our loved ones via cell phones. But then again, we are instantly and always permanently connected to a world of overwhelming information. Yes, we can Google knowledge in seconds that took many people many years to accumulate. But then again, the expectations for today’s new employees to be able to process all this information are much different than they were for employees of yesteryear.

In summary, in some ways we are all lazier and more entitled than the generations that preceded us. In addition, we all have had to face new challenges that preceding generations did not predict or experience. The constant societal evolution toward better is one big reason why it is a grave error to characterize an entire generation as lazy, entitled, disrespectful, hand-held job-hoppers.

Consider this question: What if the words “lazy” and “entitled” were used to describe another subgroup? For example, all women are lazy and entitled. This would be considered discrimination and slanderous. Even softer versions such as “Why should we pander to [ethnic group] needs?” implies discrimination instead of inclusion. Organization leaders and employees, as always, should be careful about using discriminatory language, at a minimum to avoid legal issues.

Furthermore, it is impossible to build an inclusive culture while simultaneously projecting stereotypes. Many organizations profess a desire to create an inclusive cross-generational workplace in today’s world where an unprecedented five generations are working side by side. Those same organizations, however, often knowingly and unknowingly express disrespect for millennials verbally and through behaviors.

For example, a 27-year-old millennial manager shared with me her experience with her one-up manager. The millennial had joined an organization after earning her bachelor’s and master’s degrees while working throughout college. She joined the organization at a managerial level and as a result, her gen X manager often comments, “You’re so lucky to be getting all this responsibility at your age.” Statements such as these subtly underscore the assumption that she was not deserving of her job because of her age, instead of appreciating that her strengths and experience simply fit the needs of the job. Many managers would see nothing wrong with this statement, but on the receiving end, it creates a consistent undertone of resentment.

Paul Meshanko, in his book The Respect Effect and related talks, shares his brilliant research on respect and its impact on productivity and engagement.2 He writes, “Respect biologically programs and primes our brains to do our very best work. It frees the pre-frontal complex, the most productive part of the brain that does complex problem solving, prioritizing, collaborating with people, to do its best work. When I’m treated with disrespect, that part of the brain goes silent, unable to do work.” To encourage a cross-generationally inclusive, productive atmosphere for modern talent, we need to deliberately and intentionally create an atmosphere of respect for all generations.

Meshanko goes on to explain the biological challenges of doing so and how to overcome them: “When we engage people with suspicion, our behaviors become distinctly unproductive. We go out of our way to avoid them. We can also become hostile, where we spend our energy hurting other people and their ability to contribute. The problem is we are suspicious by nature. How do we overcome that? We go back to a state of mind we had when we were children. Instead of being suspicious when we didn’t know someone, we were curious. When we can replace suspicion with curiosity, we approach each other to understand our differences and give them context.”

Reading this book, written by a millennial, is one way in which you are intentionally engaging on a journey to respectfully understand the differences and context of the millennial generation. Instead of labeling and discriminating against millennials with words like “lazy” and “entitled,” you can choose to actively become curious about, instead of suspicious of, the changes in expectation and behavior millennials are bringing forward. It may be difficult, but it will help you become proud of how you handle your everyday conversations with the newest members of the workforce. By doing so, not only are you avoiding legal repercussions, you are one step closer to building an inclusive atmosphere that creates productivity, engagement, and a commitment to dignity for all in your organization.

In the next chapters, we will explore alternative language for the five most common millennial generation stereotypes: lazy, entitled, needing to be hand-held, disloyal, and having issues with authority. Before doing so, let’s have a firm understanding of generational science and the statistics and events that influenced the millennial generation.

A generation is defined as “a cohort born in the same date range that experienced the same events during their formative years.” As a result, sociologists say that some conclusions can be drawn about the cohort’s attitudes, values, and beliefs, which comprises the essence of generational science.

Let’s explore why the focus on formative events is important. Experiencing significant events as a child is different than experiencing events as an adult. Many people today comment that innovations like the Internet haven’t just affected millennials, they’ve affected everyone. While that statement is true, adults have a predefined context with which to interpret significant events. Children, on the other hand, shape their context anew, for the first time, when significant events occur; this newly formed context then becomes the lens through which they interpret the world as adults.

In addition, children are significantly influenced by their parents. The behaviors and experiences parents share with their children as a result of events shape their kids’ context as well. For example, in the United States, we can imagine that the widely publicized Columbine high school shooting, in which two teens killed 13 people and wounded more than 20 others before committing suicide, potentially created a parenting style that overly focused on child safety, one factor in what is commonly known as “helicopter parenting.” Where once kids were allowed to roam freely, today parents keep a much tighter grip on their whereabouts. This is one of many formative events that shaped values, expectations, and beliefs differently for millennials compared to other generations.

A second component of the definition for generational science is that the conclusions drawn should aim to be about collective attitudes, values, and beliefs. To say that the millennial generation values or believes in being babied and hand-held doesn’t make sense. However, to say that the millennial generation values real-time feedback is appropriate. One statement seeks to interpret the motivation behind the behavior or value, and therefore becomes a discriminatory conclusion. The other focuses on the value held and leaves discussion open for a diverse range of why.

A common mistake is to attribute traits, values, and beliefs to a generation, when instead they are a function of age, marital status, income, or other factors. For example, when considering benefits, policies, and cultural elements for boomer employees, it’s much more useful to consider their life stage and the challenges of that stage (a function of age) than the formative events they experienced as children (the intention of generational studies).

Finally, let’s consider the cultural component of the definition of a generation. The birth date range and name of generations are typically defined differently around the world because different events have taken place historically that shaped the distinctions between generations. However, as globalization has increased facilitated by the Internet, so has the similarity of generational definition. Hence, in the highly globalized world of today, the emergence of the millennial generation is typically considered a global phenomenon, albeit with local differences that we should account for. When referring to older generations, however, we must be even more careful not to assume similarities between nations in birth date range, names, or characteristics. Some of the stereotypes we discuss may sound like a US phenomenon at first glance, but the underlying millennial behaviors are often something many cultures are experiencing.

With a complete understanding of the word “generation” in hand, let’s compare the generations today and draw some initial conclusions on the impact to the workplace.

Let’s consider the socioeconomic statistics and events that define the millennial generation.

Again, if you work for a global organization or are based in a different country, I encourage you to find the statistics that define the generations in your country of interest. In general, while the absolute values may differ, many of the trends for millennials may sound familiar because of the wide-reaching influence of digital technology. The statistics related to economic and societal trends, however, may differ significantly.

Here are how the generations are defined in the United States:

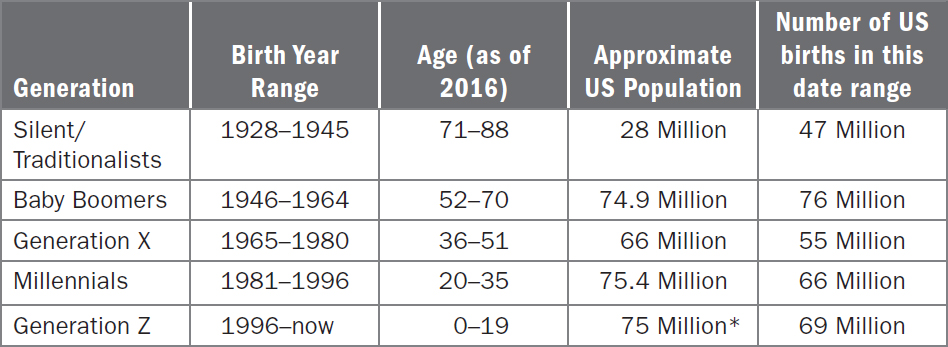

Table 1.1 Defining generations in the US

*Estimated population of generation Z as of December 2015.3

Source: Pew Research 2015 and 2016 data sets.4

A generation’s size often determines how it influences societal changes. Some of the factors that impact size of generation include birth rate, death rate, immigration rate, and the presence of conflicts such as war or environmental disasters. For example, the decreased birth rate demonstrates one reason why generation X is a smaller population. In addition to the increased birth rate, the high immigration rate for millennials has increased their overall population to 75.4 million, overtaking the 74.9 million boomers in 2016.5

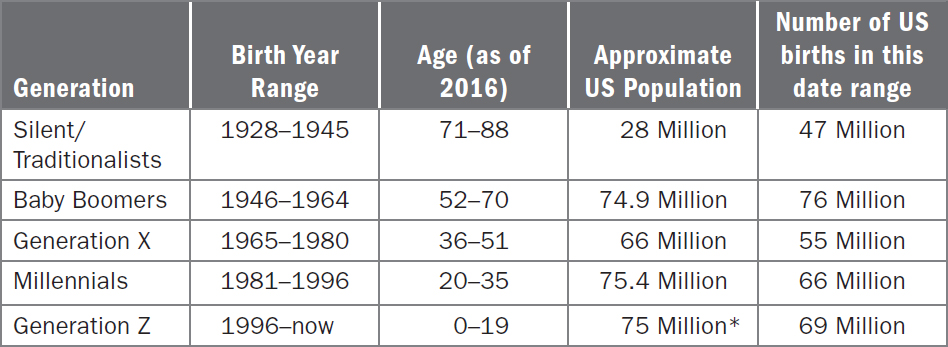

In addition to the size of each generation, other societal trends have made an impact. The battles fought for ethnic and gender equality significantly progressed during the boomer generation and the results are overwhelmingly evident in the millennial generation. For example, during the boomer generation, women made significant strides into higher education and the workforce. Today, millennials are the most educated generation in terms of number of degrees earned. In addition, females are outpacing males in this arena, with 27 percent of female millennials earning at least a bachelor’s degree compared to 21 percent of male millennials! That is nearly double the number of female boomers who held bachelor’s degrees (14 percent).6 In addition, the millennial Caucasian population in the US has fallen below 60 percent, compared to 77 percent during the boomer generation.7 Companies today with primarily Caucasian, male leadership should take notice of these changes.

Millennials are also the most diverse generation in history, not just by ethnicity but by income, parent marital status, and individual marital status. Millennials experienced a wide range of parenting styles, including the continuation of single-parent homes. Though there is much debate and diversity when calculating the rate of divorce, it’s agreed that it sharply increased during gen X’s formative years and has fallen since then, but it remains much higher than for the boomer generation. In addition, there has been a rise in homes with remarried parents and no parents. Only 46 percent of children in 2013 lived in two-parent first-marriage homes, compared to 61 percent in 1980 and 73 percent in 1960.8 Millennials are also delaying marriage significantly. Compared to 64 percent of the Silent generation and 49 percent of boomers, only 28 percent of millennials aged 18 to 32 are married.9

Lastly, inflation and recession have hit millennials hard. Underemployment and unemployment are still highest for the millennial generation compared to other generations, more than eight years after the recession. In addition, college costs have risen exponentially, from $929 per year in 1963 to $17,474 per year in 2013 for four-year public colleges (stated in 2015 dollars). For private institutions, the jump is even more drastic, from $1,810 in 1963 to $35,074 in 2013.10 This is in sharp contrast to the relatively favorable economic prospects for boomers upon graduation, when a college degree essentially guaranteed a job and didn’t require an enormous debt.

Table 1.2 Summary of generational socioeconomic trends.

Sources: Pew Research Center, National Center for Education Statistics.11

What do these societal trends indicate regarding the workplace? There are several initial conclusions we can draw from the above statistics:

› Short-term trend (next 5 to 10 years)—accelerated leadership development of millennials. Reviewing the population statistics, in the US, there are not enough gen Xers to fill the leadership gaps left behind by boomers. As boomers retire, gen Xers will be taking on an increased workload if millennials haven’t been adequately prepared to step in. Organizations that currently lack mentoring and have unstructured training programs will find they have a hard time accelerating development compared to those that do. Gen Z will likely have a similar population size as millennials, so this particular demographic shift is specific for today’s generation transition. For first world countries, this trend is generally the case. For some third world countries, often up to 50 percent of the population is composed of those under the age of 25 and therefore, there are differing challenges.

› Mid-term trend (next 30 years)—job-hopping due to lack of trust in organizations. Instead of preparing for a midlife crisis, millennials often intend to have a quarter-life crisis. For many, this is a direct result of witnessing higher divorce rates and parents who have experienced layoffs, benefit reductions, and regrets about putting their eggs in one, usually unfulfilling, basket during the Great Recession. Millennials are spending more time in their early career years exploring self and their passions. Delaying marriage also allows for pursuing careers for exploration instead of “for the paycheck.” Organizations that help them discover and leverage their strengths and passions, while having a clear commitment to valuing employees, have a distinct advantage with talent that has witnessed the recession. Gen Z has been affected similarly. If the global economy continues to recover and trust is rebuilt, this trend could be partially reversed.

› Long-term trend (beyond 30 years)—engaging a highly diverse population. It is very difficult to characterize millennials in the workplace because of their much greater diversity than previous generations, including their gender, ethnicity, income background, and parenting style. With more than half of the college graduates being female and only 60 percent being Caucasian, we can expect a wider variety of expectations. Because of this diversity, the common attributes of “everyone gets a trophy” or being reared by “helicopter parents” don’t necessarily ring true across the full generation. Eric Hoover was pointed in his criticism of the generational labels: “Over the last decade, commentators have tended to slap the millennial label on white, affluent teenagers who accomplish great things as they grow up in the suburbs, who confront anxiety when applying to super-selective colleges, and who multi-task with ease as their helicopter parents hover reassuringly above them. The label tends not to appear in renderings of teenagers who happen to be minorities or poor, or who never won a spelling bee.”12 Similarly, gen Z and generations to come will have greater diversity, especially with increasing globalization. Modern talent is diverse and expects diversity to be present and respected in the workplace.

In addition to the socioeconomic reasons, the way we work, study, and live has also been dramatically changed by the evolution of the computer, the Internet, social media, and mobile devices. Understandably, the tools millennials grew up using in school have translated to expectations of the workplace.

Consider the following trends. As you review, if you are a nonmillennial, consider the world you grew up in instead and how the messages and tools you had exposure to may have been different.

› What children can learn has changed drastically. It’s an undeniable fact that young people have access to greater amounts of information via the Internet and have the opportunity to learn more than previous generations did at the same age. As much as we often hate to admit it, people graduating today have a lot more knowledge in topics that are relevant today than they are given credit for. High school students, for example, participate on robotics teams instead of playing outside with no rules. As stated before, however, with any innovation, some skills are gained, some are transformed, and some are lost. Kids today may not learn at all about some skills that are considered basic knowledge by previous generations.

› Children can gain respect through sharing their voice. Regardless of age, everyone is able to contribute their voice to the Internet and gain a following. The Internet is the great equalizer. Teens have a greater entrepreneurial spirit, desire to pursue potential, and a different skill set than graduates of previous generations as a result of their exposure to digital technology and the Internet.

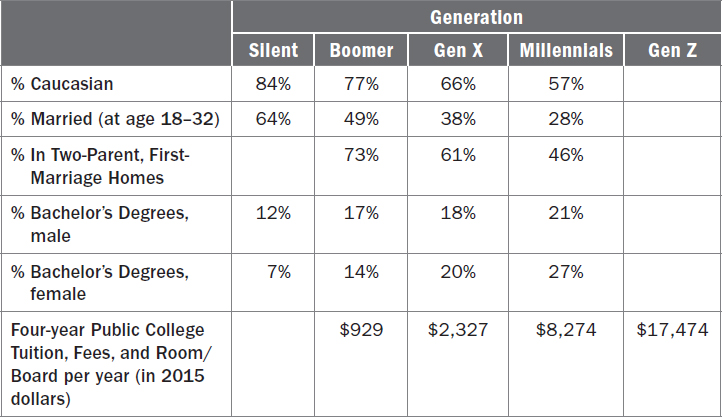

› The type of work done in organizations has changed. For the general employee base, the type of jobs available has shifted drastically from routine manual (10 percent loss since 2001) and routine cognitive (8 percent loss) to nonroutine cognitive (+24 percent growth) and nonroutine manual (+32 percent growth).13 Furthermore, the days of the intern making copies and bringing coffee are disappearing rapidly. New employees are expected to become contributors rapidly as a result of today’s VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous) business environment. This change is a key contributor to this book’s focus on top talent millennials who work in highly cognitive, nonroutine roles.

› The way workers communicate and interact has changed. The ability to work virtually and impact across global boundaries has exponentially increased. The amount of time spent outdoors and/or face-to-face has decreased. Relationship and communication skills are shifting. Kids today have grown up contributing to social campaigns to help other countries during times of need. They are often more comfortable communicating behind a screen than in person.

Figure 1.1 Employment in routine vs. nonroutine jobs has diverged since 200114

In summary, the millennial generation is exquisitely diverse, exposed to more information at younger ages than previous generations and dealing with new-to-the-world obstacles, because of the technological and social changes present in their formative years. They are a reflection of a wide variety of parenting styles, backgrounds, education systems, world events, and innovations. They are a living, breathing example of how the groundbreaking innovations of the last 50 years have impacted and will continue to impact society. These rapid changes explain why the gap between generations today is so wide, in the US and even more so in third world countries. Some of the approaches millennials use are important signs of changes to the status quo; some are signs of what we risk losing if we aren’t careful. They allow us to question and reexamine our assumptions for how we work and live today. When millennial workplace expectations are considered inappropriate, are leaders and managers taking into account a well-rounded perspective on the impact of these socioeconomic and technological changes?

Older generation leaders who successfully understand millennials often are motivated by highly personal reasons. One such champion I encountered had experienced a tragedy with the death of her teenage son. During this time, she experienced a wide amount of support from her son’s friends, who created fund-raisers and nonprofit efforts in her son’s name using social media. Since that time, she has never agreed with the stereotypes about millennials. In another instance, Lee, an “on the cusp” gen X/boomer, spent a great deal of time with his daughter’s rowing team as their unofficial photographer. He witnessed such high collaboration, dedication, and perseverance, it was forever imprinted in his mind that this generation is yet another great generation. He wanted to support the generation in any way he could, especially in light of the overall perception. Once a stranger to me, he reached out to find opportunities for me to help spread the belief he felt so strongly about. In these very personal moments of transformation, one gains a sense of appreciation of being in the others’ shoes. What have we learned from successful cross-generational relationships? Consider the power these individuals have discovered by integrating our different lenses into a more complete view.

At this point, we should be grounded in why this is an important topic for business, why lazy and entitled are ineffective conclusions, what the definition of a generation is, and the big picture of socioeconomic and innovation trends that have impacted the various generations. Now we are ready to explore the five most common stereotypes in detail and what they really tell us about the modern workplace instead. Through the thought processes, stories, and best practices presented, reflect on your ability to speak a new language and consider what actions you will take as a modern workplace champion.