SEM images that show the spatial distribution of the elemental constituents of a specimen (“elemental maps”) can be created by using the characteristic X-ray intensity measured for each element with the energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) to define the gray level (or color value) at each picture element (pixel) of the scan. Elemental maps based on X-ray intensity provide qualitative information on spatial distributions of elements. Compositional mapping, in which a full EDS spectrum is recorded at each pixel (“X-ray Spectrum Imaging” or XSI) and processed with peak fitting, k-ratio standardization, and matrix corrections, provides a quantitative basis for comparing maps of different elements in the same region, or for the same element from different regions.

24.1 Total Intensity Region-of-Interest Mapping

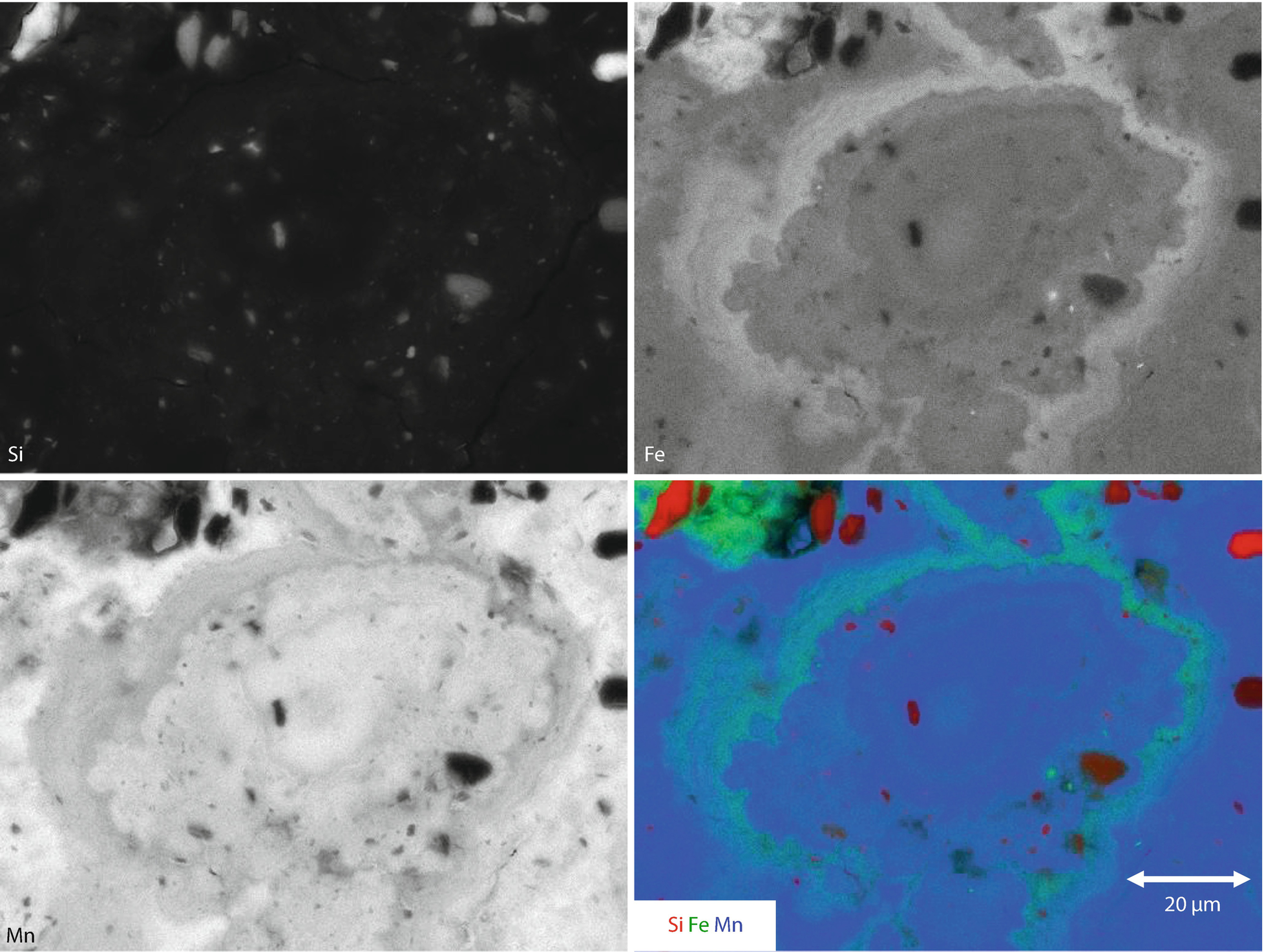

EDS spectrum measured on a cross section of a deep-sea manganese nodule showing peak selection (Si K-L2, Mn K-L2,3, and Fe K-M2,3) for total intensity elemental mapping

Total intensity elemental maps for Si K-L2, Mn K-L2,3, and Fe K-M2,3 measured on a cross section of a deep-sea manganese nodule, and the color overlay of the gray-scale maps

◘ Figure 24.2 also contains a primary color overlay of these three elements, encoded with Si in red, Fe in green, and Mn in blue, a commonly used image display tool which provides an immediate visual comparison of the relative spatial relationships of the three constituents. The appearance of secondary colors shows areas of coincidence of any two elements, for example, the cyan colored region is a combination of green and blue and thus shows the coincidence of Fe and Mn. The other possible binary combinations are yellow (red plus green, Si + Fe) and magenta (red plus blue, Si + Mn), which are not present in this example. If all three elements were present at the same location, white would result.

24.1.1 Limitations of Total Intensity Mapping

- 1.

By selecting only the spectral regions-of-interest, the amount of mass storage is minimized. However, while all spectral regions-of-interest are collected simultaneously, if the analyst needs to evaluate another element not originally selected when the data was collected, the entire image scan must be repeated to recollect the data with that new element included.

- 2.

Total intensity maps convey qualitative information only. The elemental spatial distributions are meaningful only in qualitative terms of interpreting which elements are present at a particular pixel location(s) by comparing different elemental maps of the same area, for example, using the color overlay method. Since the images are recorded simultaneously, the pixel registration is without error even if overall drift or other distortion occurs. However, the intensity information is not quantitative and can only convey relative abundance information within an individual elemental map (e.g., “this location has more of element A than this location because the intensity of A is higher”). The gray levels in maps for different elements cannot be readily compared because the X-ray intensity for each element that defines the gray level range of the map is determined by the local concentration and the complex physics of X-ray generation, propagation, and detection efficiency, all of which vary with the elemental species. The element-to-element differences in the efficiency of X-ray production, propagation, and detection are embedded in the raw measured X-ray intensities, which are then subjected to the autoscaling operation. Unless the autoscaling factor is recorded (typically not), it is not possible after the fact to recover the information that would enable the analyst to standardize and establish a proper basis for inter-comparison of maps of different elements, or even of maps of the same element from different areas. Thus, the sequence of gray levels only has interpretable meaning within an individual elemental map. Gray levels cannot be sensibly compared between total intensity maps of different elements, for example, the near-white level in the autoscaled maps of ◘ Fig. 24.2 for Si, Fe, and Mn does not correspond to the same X-ray intensity or concentration for three elements. Because of autoscaling, it is not possible to compare maps for the same element “A” from two different regions, even if recorded with the same dose conditions, since the autoscaling factor will be controlled by the maximum concentration of “A,” which may not be the same in two arbitrarily chosen regions of the sample.

- 3.

This lack of quantitative information in elemental total intensity maps extends to the color overlay presentation of elemental maps seen in ◘ Fig. 24.2. The color overlay is useful to compare the spatial relationships among the three elements, but the specific color observed at any pixel only depicts elemental coincidence not absolute or relative concentration. The particular color that occurs at a given pixel depends on the complex physics of X-ray generation, propagation, and detection as well as concentration, and the autoscaling of the separate maps that precedes the color overlay, which distorts the apparent relationships among the elemental constituents, also influences the observed colors.

- 4.

When peak interference occurs, the raw intensity in a given energy window may contain contributions from another element, as shown in ◘ Fig. 24.1 where the region that includes Fe K-L2,3 also contains intensity from Mn K-M2,3. While choosing the non-interfered peak Fe K-M2,3 gives a useful result in the case of the manganese nodule, if the specimen also contained cobalt at a significant level, Co K-L2,3 (6.930 keV) would interfere with Fe K-M2,3 (7.057 keV) and invalidate this strategy. The peak interference artifact can be corrected by peak fitting, or by methods in which the measured Mn K-L2,3 intensity, which does not suffer interference in this particular case, is used to correct the intensity of the Fe K-L2,3 + Mn K-M2,3 window using the known Mn K-M2,3/K-L2,3 ratio.

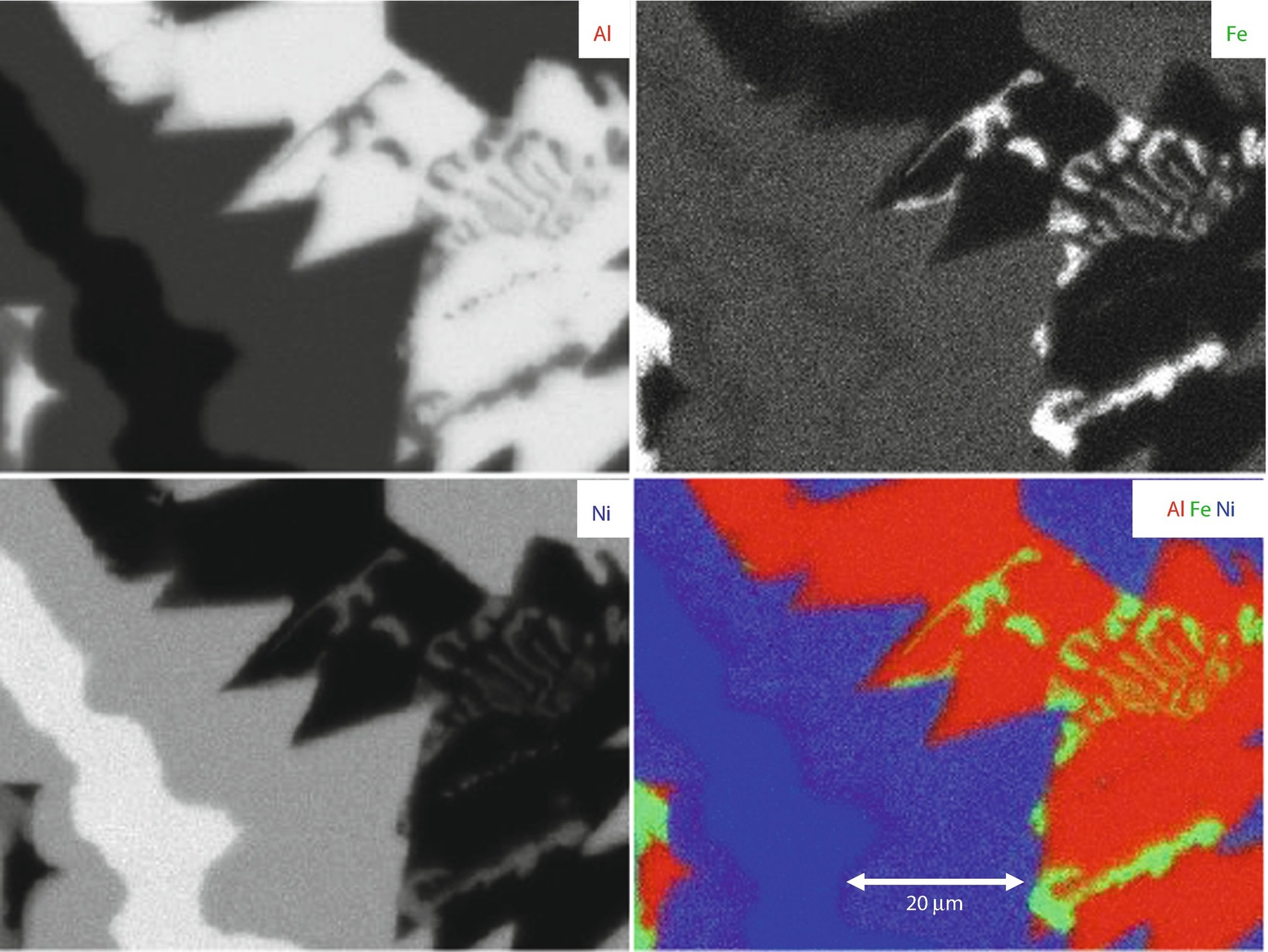

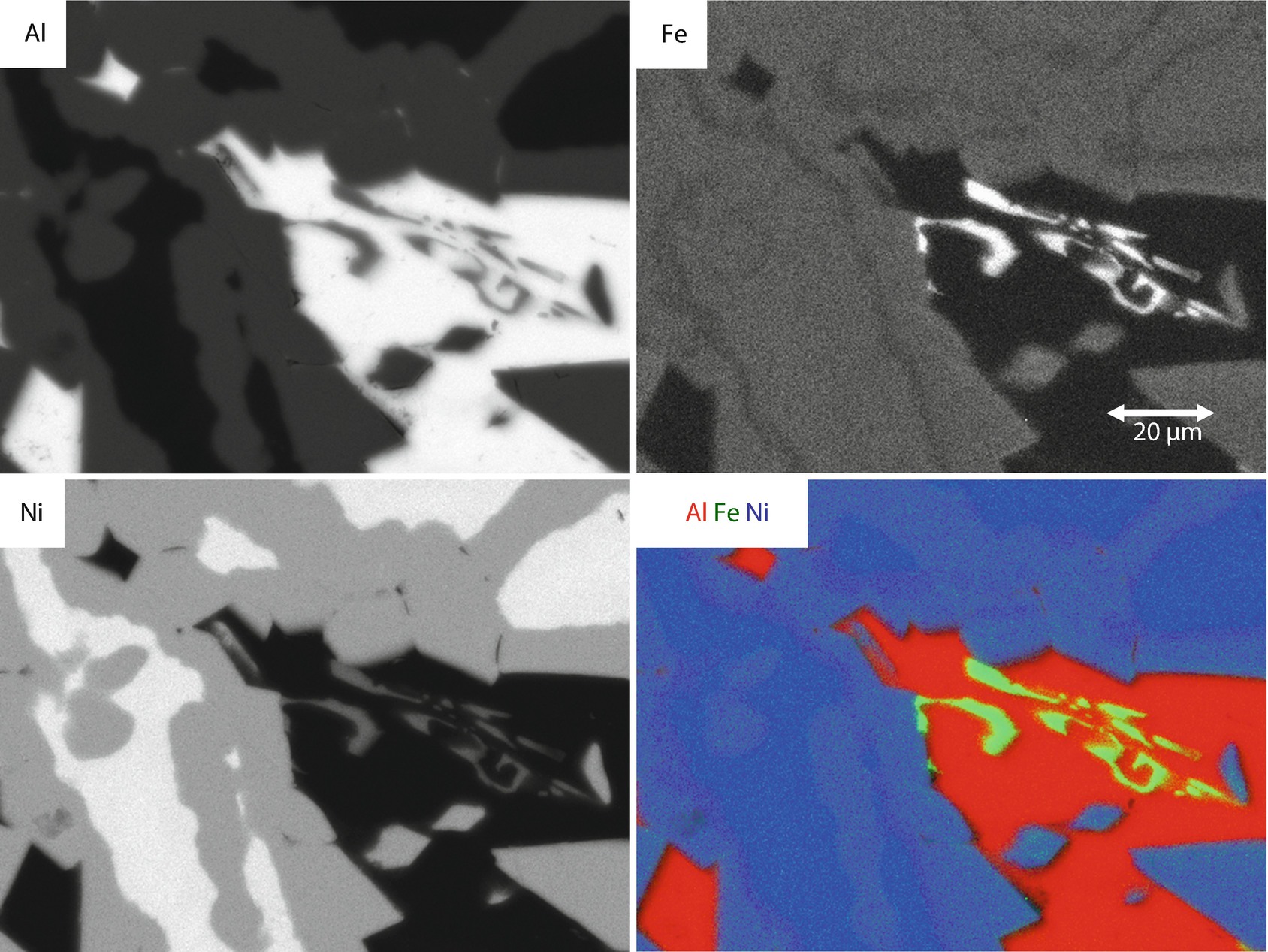

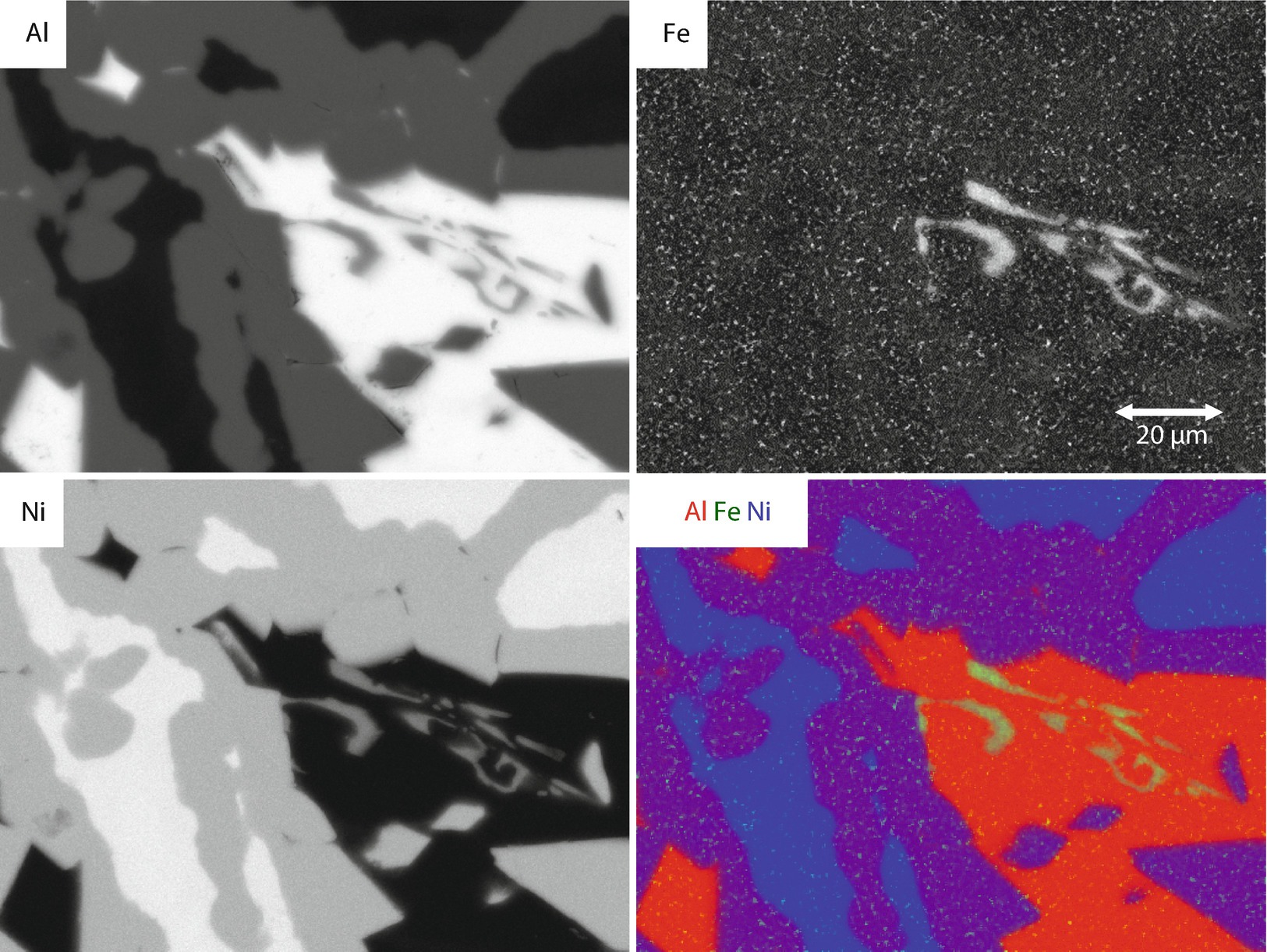

- 5.The total intensity window contains both the characteristic peak intensity that is specific to an element and the continuum (background) intensity, which scales with the average atomic number of all of the elements within the excited interaction volume but is not exclusively related to the element that is generating the peak. For the map of an element that constitutes a major constituent (mass concentration C >0.1 or 10 wt %), the non-specific background intensity contribution usually does not constitute a serious mapping artifact. However, for a minor constituent (0.01 ≤ C ≤ 0.1, 1 wt % to 10 wt %), the average atomic number dependence of the continuum background can lead to serious artifacts. ◘ Figure 24.3 shows an example of this phenomenon for a Raney nickel alloy containing major Al and Ni with minor Fe. The complex microstructure has four distinct phases, the compositions of which are listed in ◘ Table 24.1, one of which contains Fe as a minor constituent at a concentration of approximately C = 0.04 (4 wt %). This Fe-rich phase can be readily discerned in the Fe gray-scale map, where the intensity of this phase, being the highest iron-containing region in the image, has been autoscaled to near white. In addition to this Fe-containing phase, there appears to be segregation of lower concentration levels of Fe to the Ni-rich phase relative to the Al-rich phase. However, this effect is at least partially due to the increase in the continuum background in the Ni-rich region relative to the Al-rich region because of the sharp difference in the average atomic number. For trace constituents (C < 0.01, 1 wt %), the atomic number dependence of the continuum background can dominate the observed contrast, creating artifacts in the images that render most trace constituent maps nearly useless.

Fig. 24.3

Fig. 24.3Total intensity elemental maps for Al K-L2 (major), Fe K-L2,3 (minor), and Ni K-L2,3 (major) measured on a cross section of a Raney nickel alloy, and the color overlay of the gray-scale maps

Table 24.1Phases in Raney nickel; as measured by electron-excited X-ray microanalysis (mass concentrations)

Al

Fe

Ni

High Al

0.995

0

0.005

Fe-rich

0.712

0.042

0.246

Intermediate Ni

0.600

0

0.400

High Ni

0.465

0

0.535

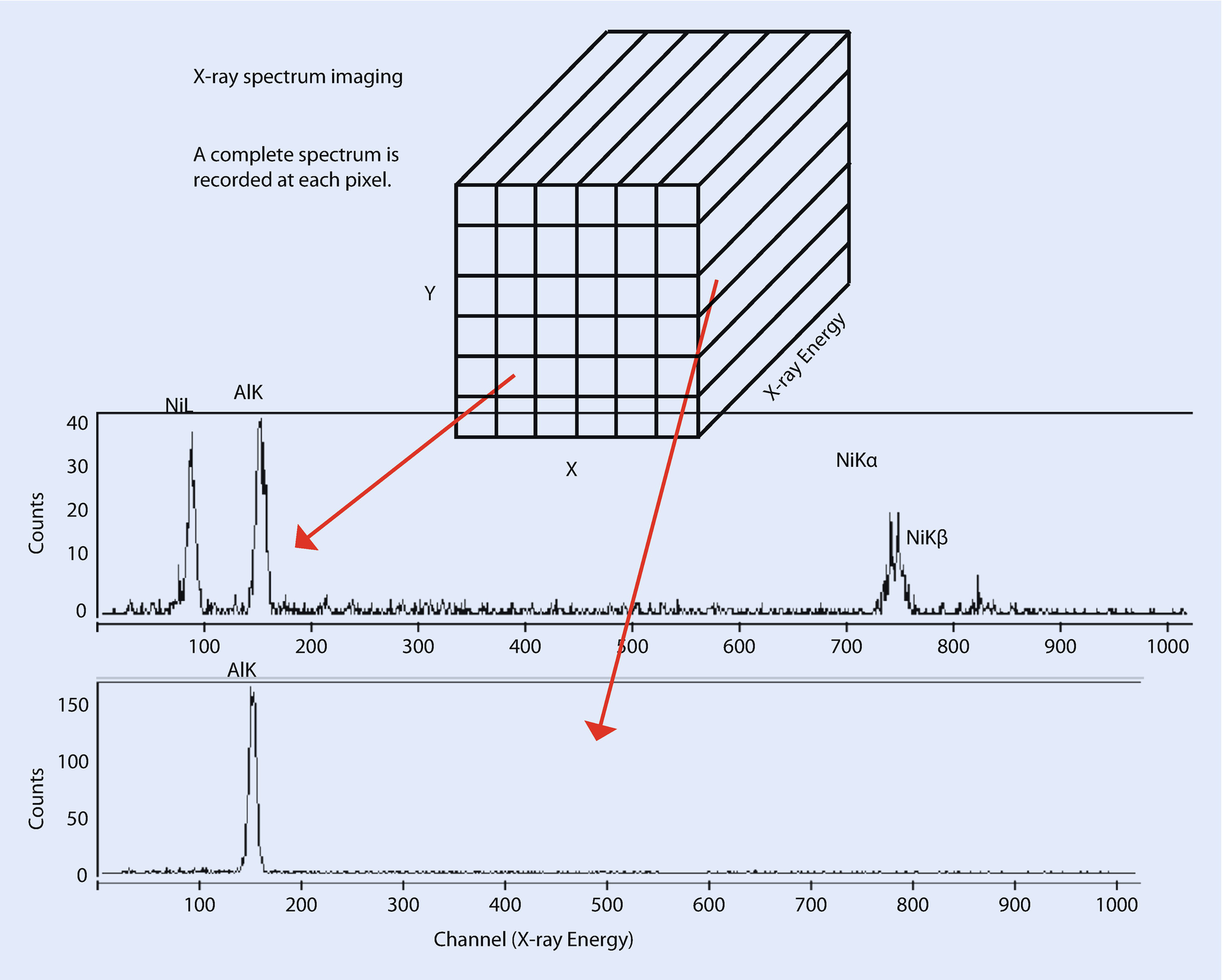

24.2 X-Ray Spectrum Imaging

X-ray spectrum imaging (XSI) involves collecting the entire EDS spectrum, I(E), at each pixel location, producing a large data structure [x, y, I(E)] typically referred to as a “datacube” (Gorlen et al. 1984; Newbury and Ritchie, 2013). Alternatively, the data may be recorded as “position-tagged” photons, whereby as each photon with energy Ep is detected, it is tagged with the current beam location (x, y), giving a database of values (x, y, E p) which can be subsequently sampled with rules defining the range of Δx and Δy over which to construct a spectrum I(E) at a single pixel or over a defined range of pixels. Depending on the number of pixels and the intensity range of the X-ray count data, the recorded XSI can be very large, ranging from hundreds of megabytes to several gigabytes. Vendor software usually compresses the datacube to save mass storage space, but the resulting compressed datacube can only be decompressed and viewed with the vendor’s proprietary software. As an important alternative, if the datacube can be saved in the uncompressed RAW format (a simple block of bytes with a header or an associated file that carries the metadata needed to read the file), the RAW file can be read by publically available, open source software such as NIH ImageJ-Fiji or NIST Lispix (Bright, 2017).

X-ray spectrum image considered as a datacube of pixels x, y, I(E)

X-ray spectrum image considered as a stack of x, y images, each corresponding to a specific photon energy E p

24.2.1 Utilizing XSI Datacubes

In the simplest case, by capturing all possible X-ray information about an imaged region, the XSI permits the analyst to define regions-of-interest for total intensity mapping at any time after collecting the map datacube, creating elemental maps such as those in ◘ Fig. 24.2. If additional information is required about other elements not in the initial set-up, there is no need to relocate the specimen area and repeat the map since the full spectrum has been captured in the XSI.

The challenge to the analyst is to make efficient use of the XSI datacube by discovering (“mining”) the useful information that it contains. Software for aiding the analyst in the interpretation of XSI datacubes ranges from simple tools in open source software to highly sophisticated, proprietary vendor software that utilizes statistical comparisons to automatically recognize spatial correlations among elements present in the specimen region that was mapped (Kotula et al. 2003).

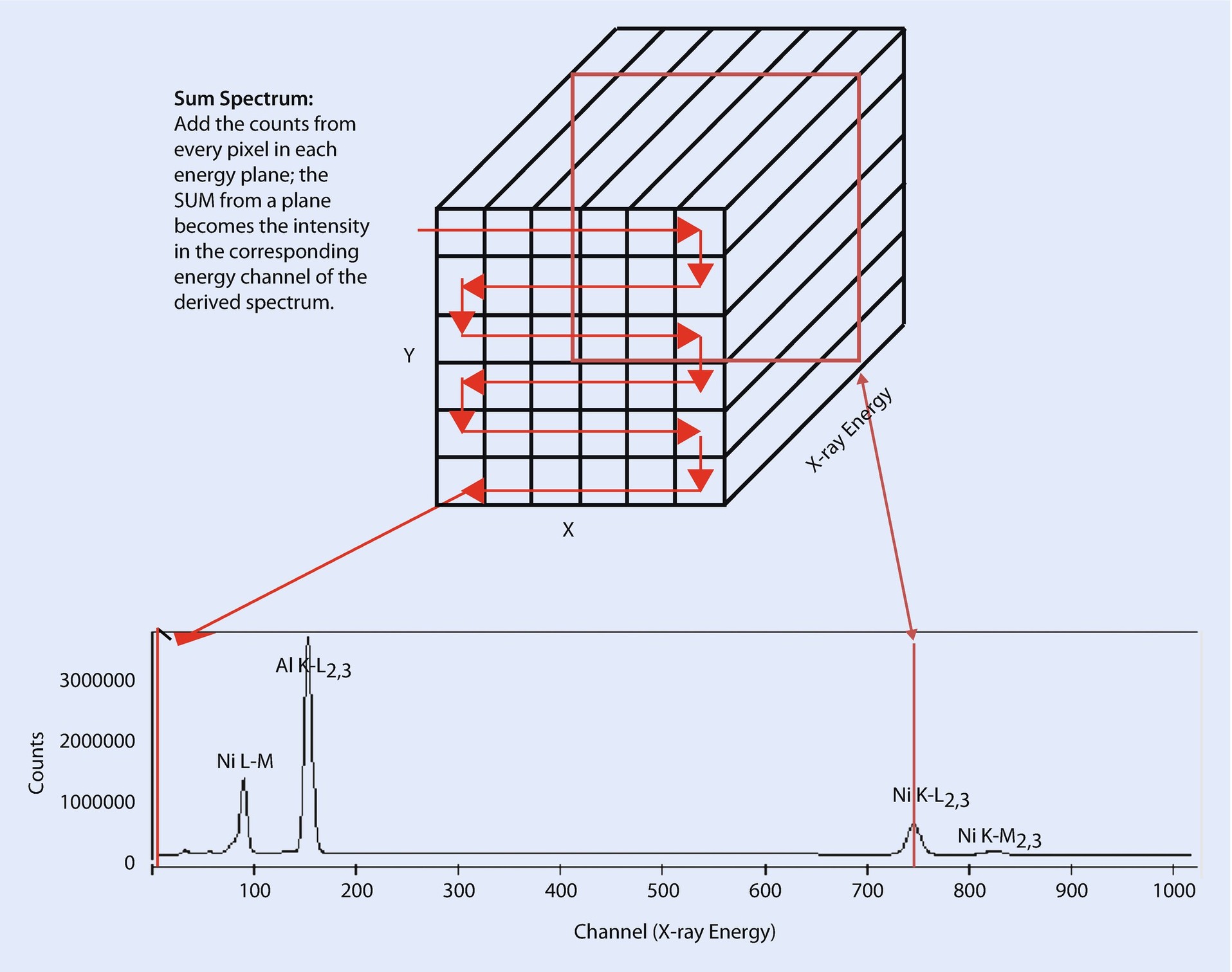

24.2.2 Derived Spectra

24.2.2.1 SUM Spectrum

Concept of the SUM spectrum derived from an X-ray spectrum image by adding the counts from all pixels on an individual image at a specific photon energy, E p

Using the SUM spectrum to interrogate an X-ray spectrum image to find the dominant elemental peaks for the region being mapped

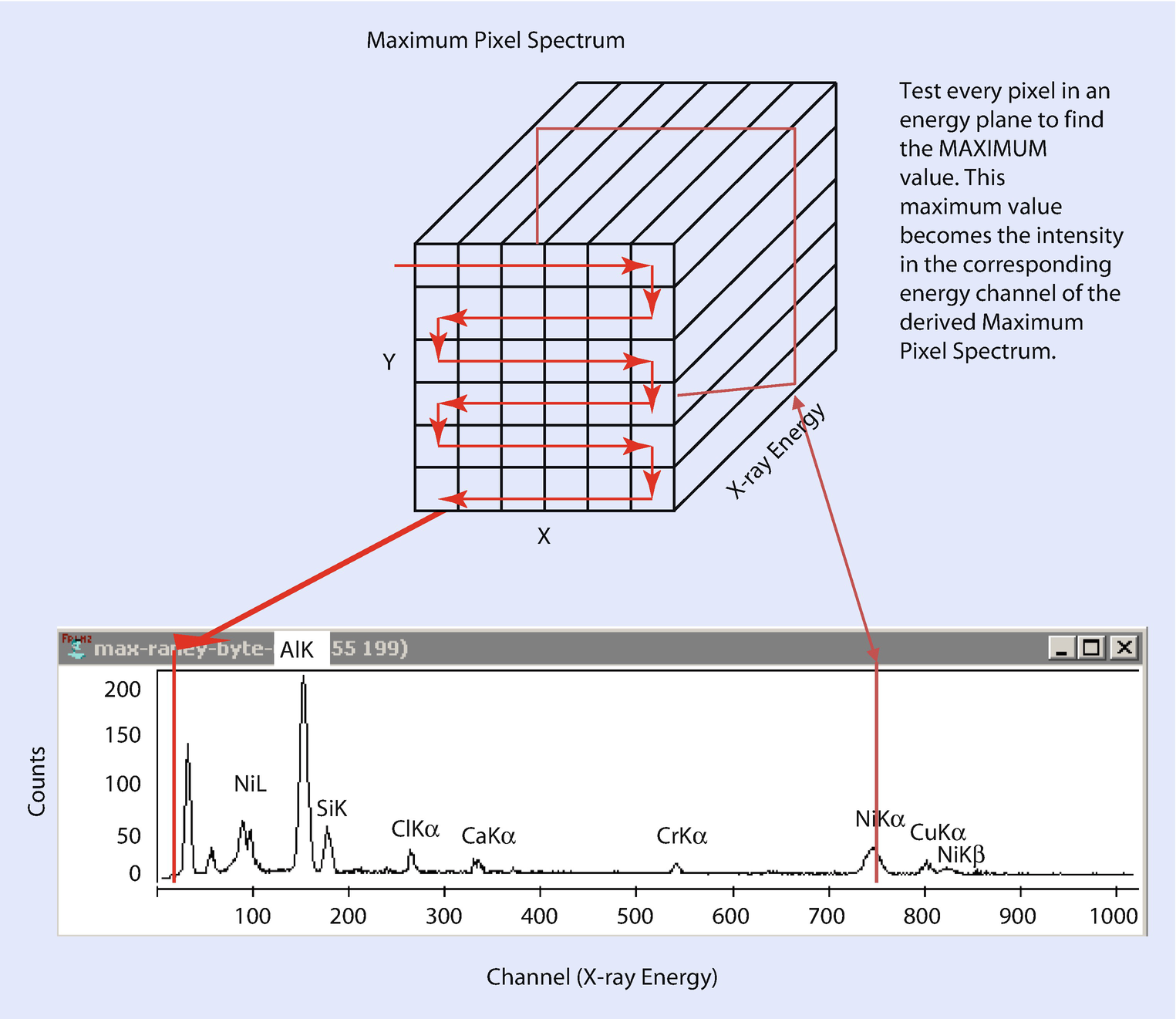

24.2.2.2 MAXIMUM PIXEL Spectrum

Concept of the MAXIMUM PIXEL spectrum derived from an X-ray spectrum image by finding the highest count among all the pixels on an individual image at a specific photon energy, E p

Use of the MAXIMUM PIXEL spectrum to identify and locate an unexpected Cr-rich inclusion in Raney nickel alloy

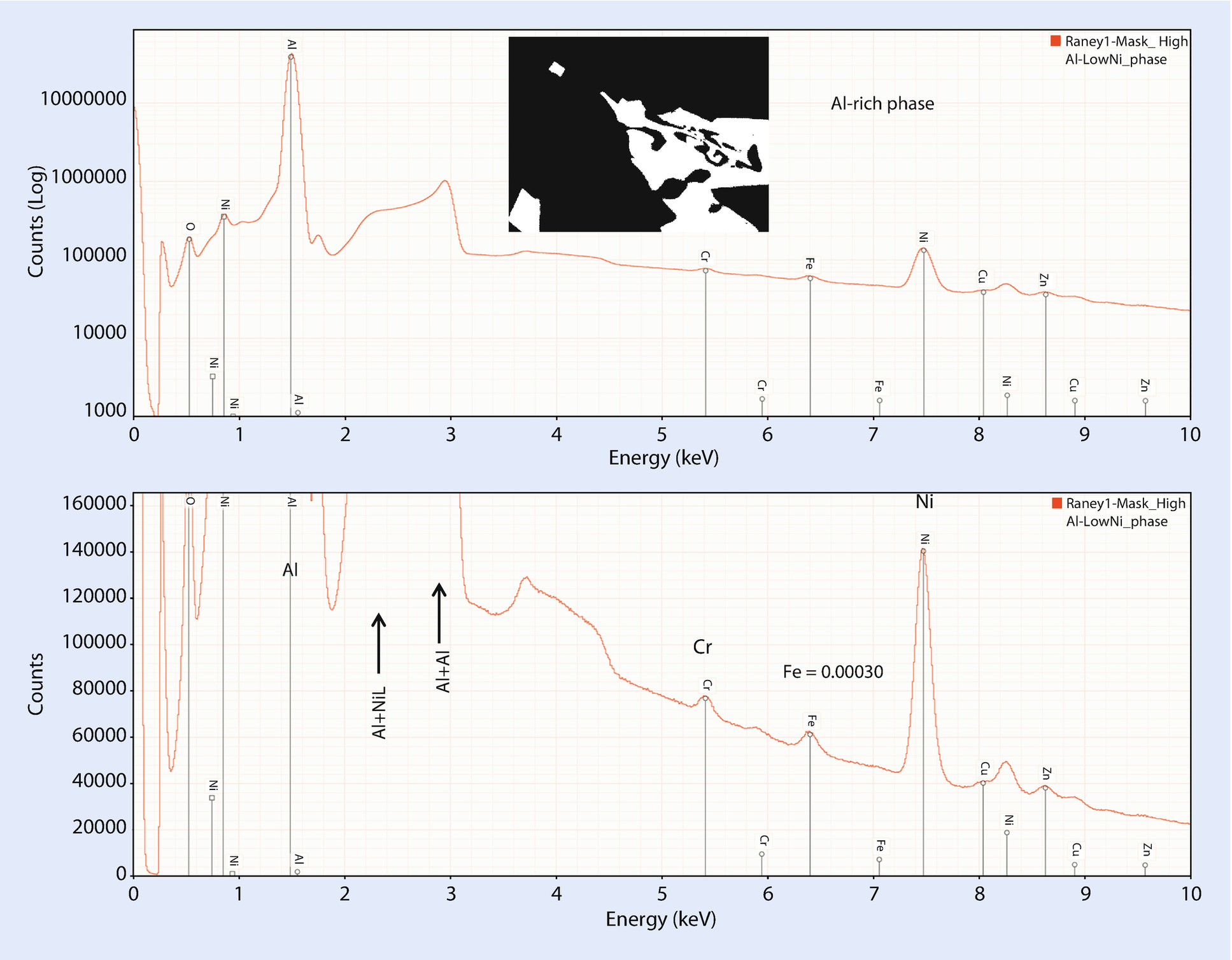

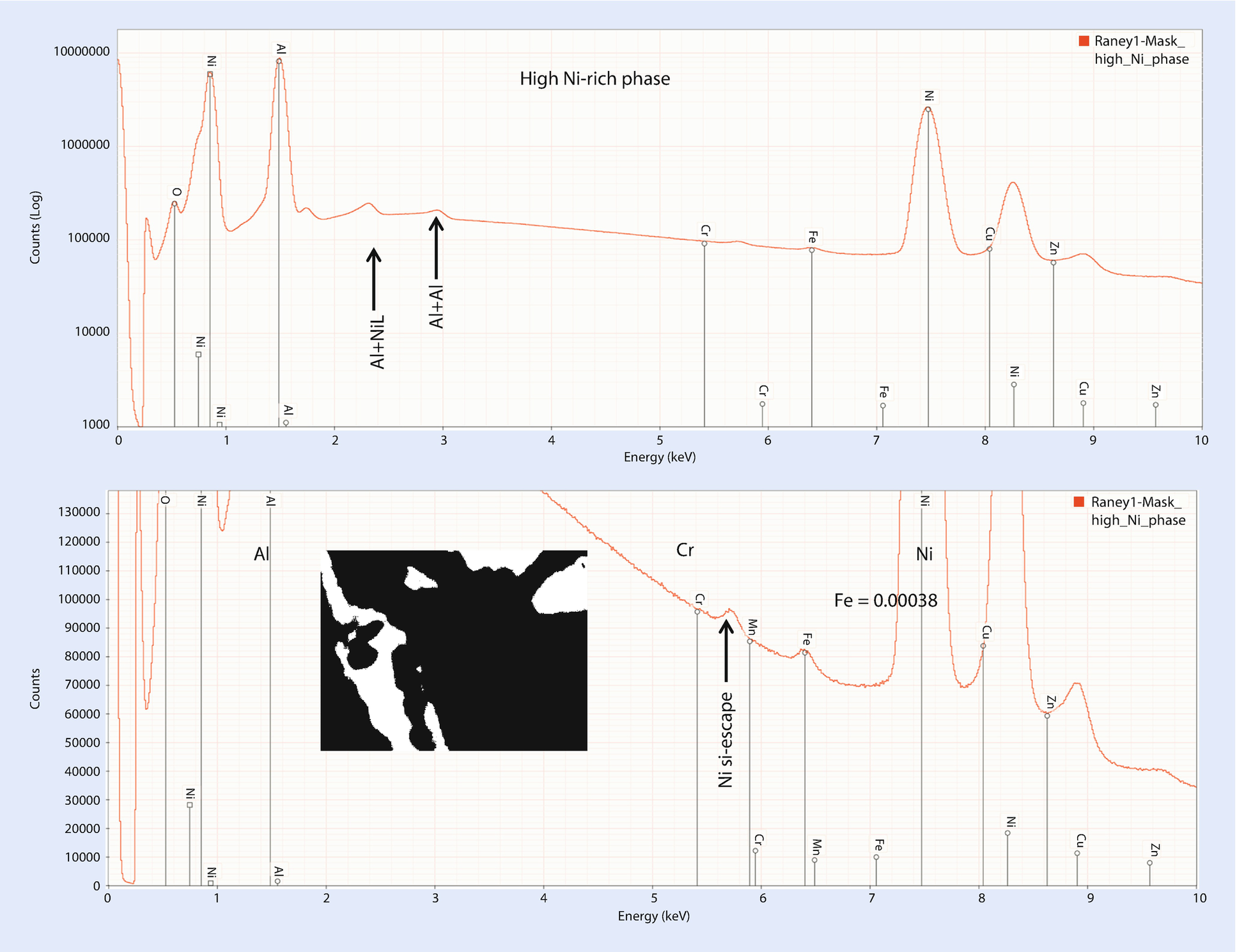

Creation of a pixel mask (inset) using the Fe elemental map for Raney nickel to select pixels from which a SUM spectrum is constructed for the Fe-rich phase

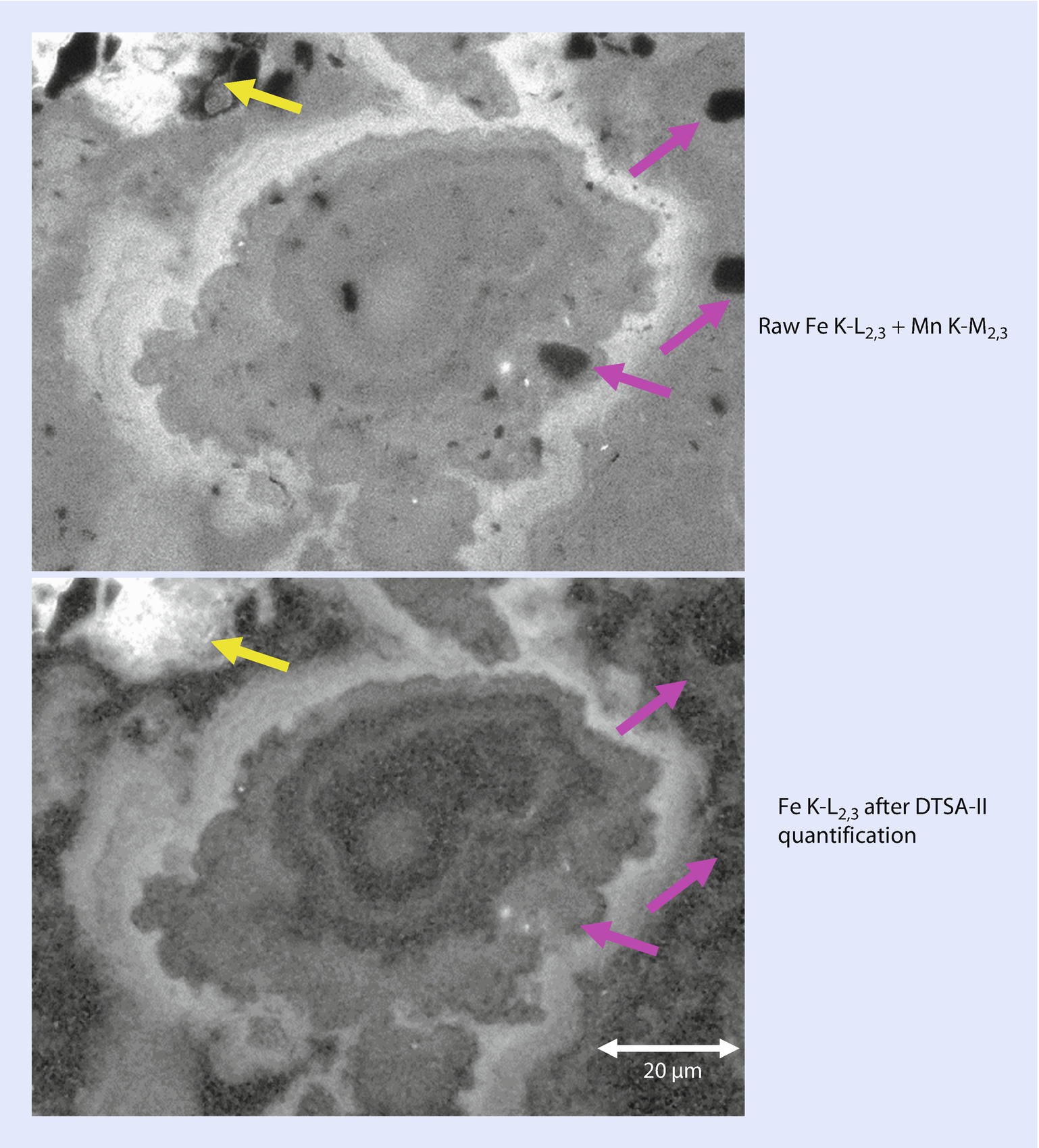

24.3 Quantitative Compositional Mapping

Quantitative compositional mapping with DTSA-II on the XSI of a deep-sea manganese nodule from ◘ Fig. 24.2: direct comparison of the total intensity map for Fe and the quantitative compositional map of Fe; note the decrease in the apparent Fe in the high Mn portion in the center of the image after quantification and local changes indicated by arrows (yellow shows extension of high Fe region; magenta shows elimination of dark features)

Raney nickel alloy XSI: total intensity maps for Al, Fe, and Ni with color overlay

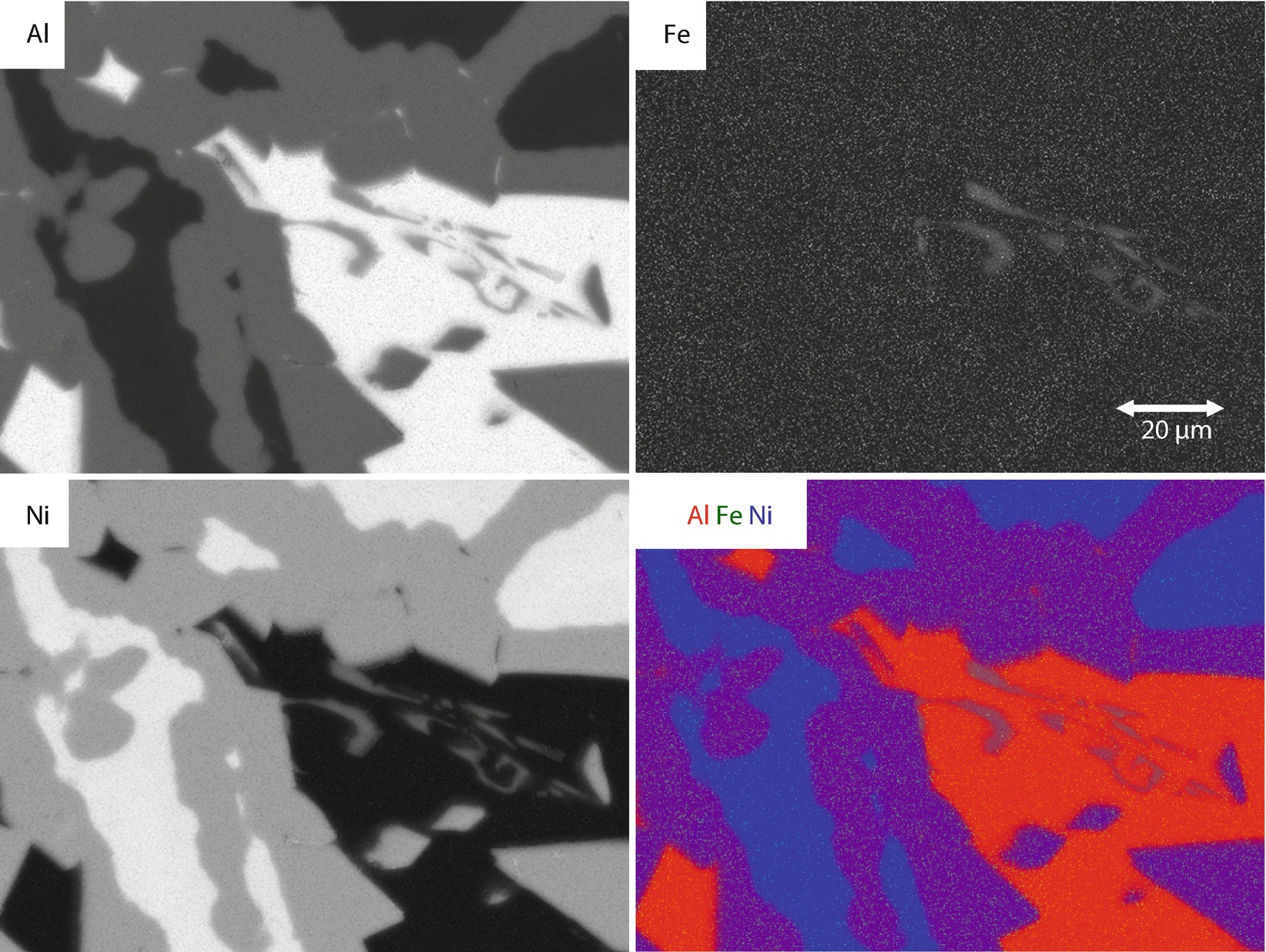

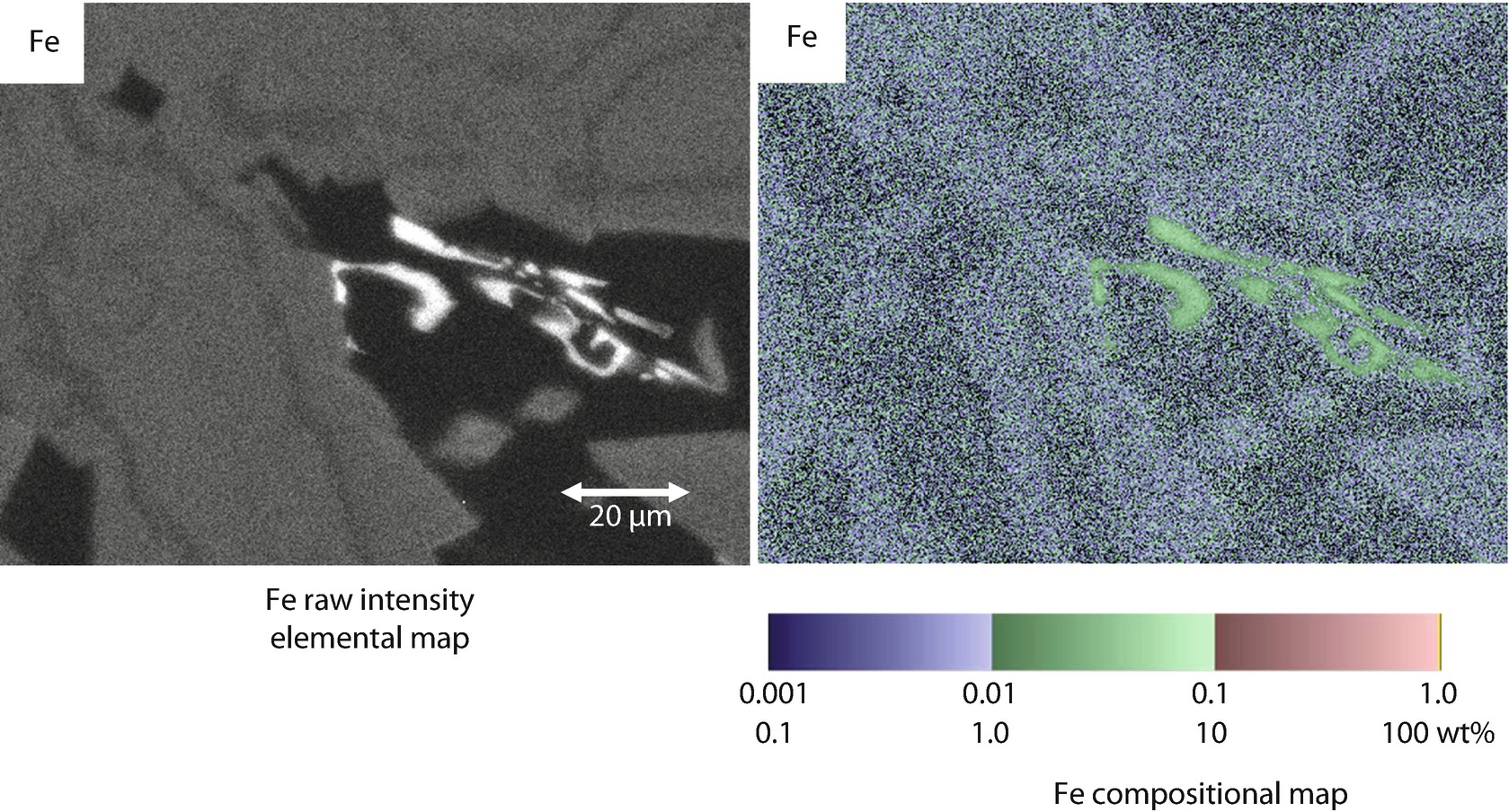

Quantitative compositional maps of the Raney nickel alloy XSI in 24.13; note low contrast in the Fe image presented without autoscaling

Quantitative compositional maps Raney nickel alloy XSI with contrast enhancement of the Fe map

Five band pseudo-color presentation of the quantitative compositional maps for Al, Fe, and Ni derived from the Raney nickel alloy XSI

Major: C > 0.1 to 1 (mass fraction) deep red to red pastel

Minor: 0.01 ≤ C ≤ 0.1 deep green to green pastel

Trace: 0.001 ≤ C < 0.01 deep blue to blue pastel

Logarithmic Three-Band Color encoding of the quantitative compositional maps for Al, Fe, and Ni derived from the Raney nickel alloy XSI

Direct comparison of the Fe total intensity map and the Logarithmic Three-Band Encoding of the Fe quantitative compositional map. Note the distinct changes in the contrast within the trace concentration (C < 0.01) regions of the image

Raney nickel alloy XSI: mask of pixels corresponding to the Fe-rich phase and the corresponding SUM spectrum; the Fe peak corresponds to C = 0.044 mass fraction

Raney nickel alloy XSI: mask of pixels corresponding to the Al-rich phase and the corresponding SUM spectrum; note the low level peaks for Fe and Cr; the Fe-peak corresponds to C = 0.00030 = 300 parts per million

Raney nickel alloy XSI: mask of pixels corresponding to the intermediate Ni-rich phase and the corresponding SUM spectrum; note the low level peak for Fe; the Fe-peak corresponds to C = 0.0027 = 2700 parts per million

Raney nickel alloy XSI: mask of pixels corresponding to the high Ni-rich phase and the corresponding SUM spectrum; note the low level peak for Fe; the Fe-peak corresponds to C = 0.00038 = 380 parts per million

24.4 Strategy for XSI Elemental Mapping Data Collection

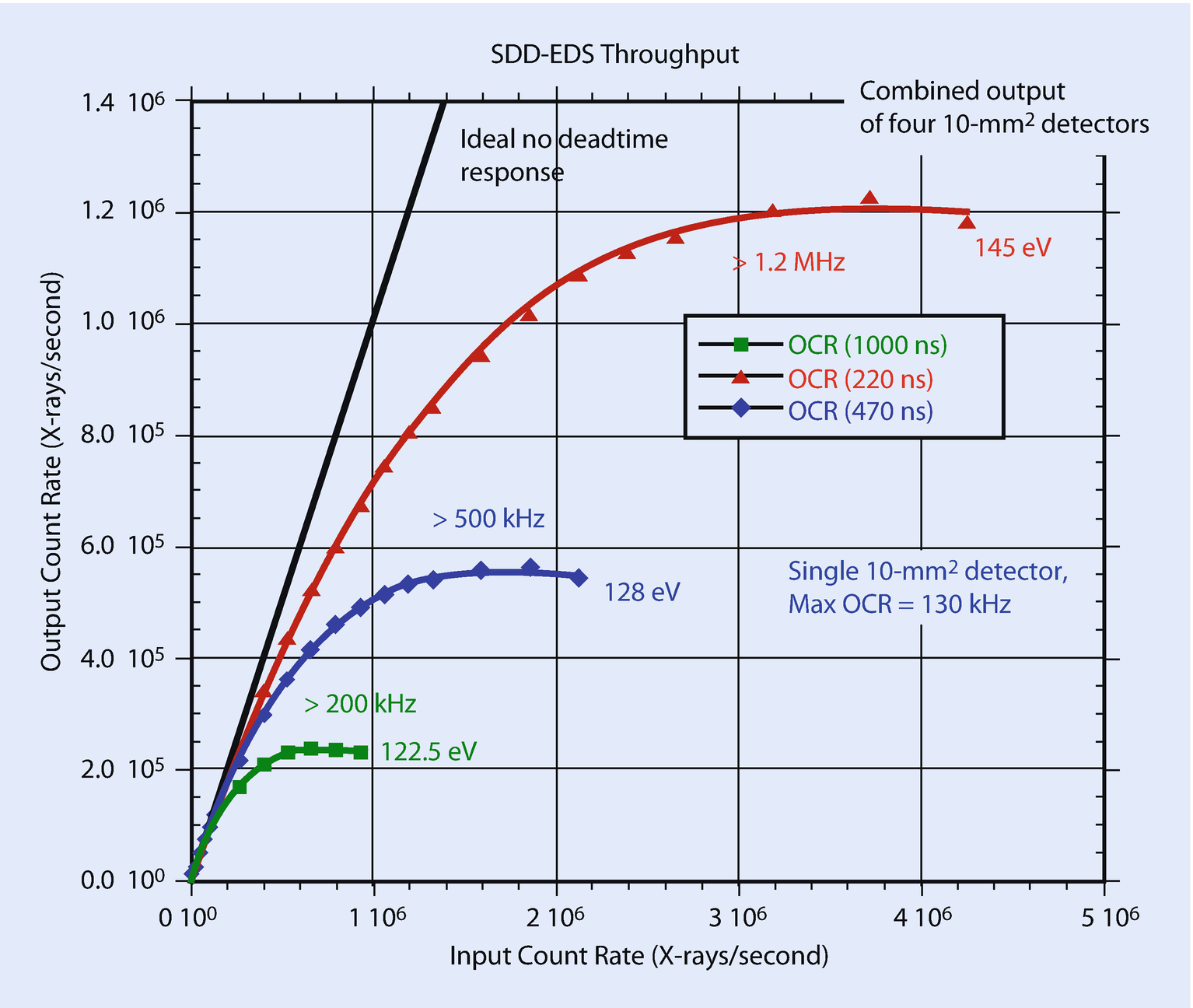

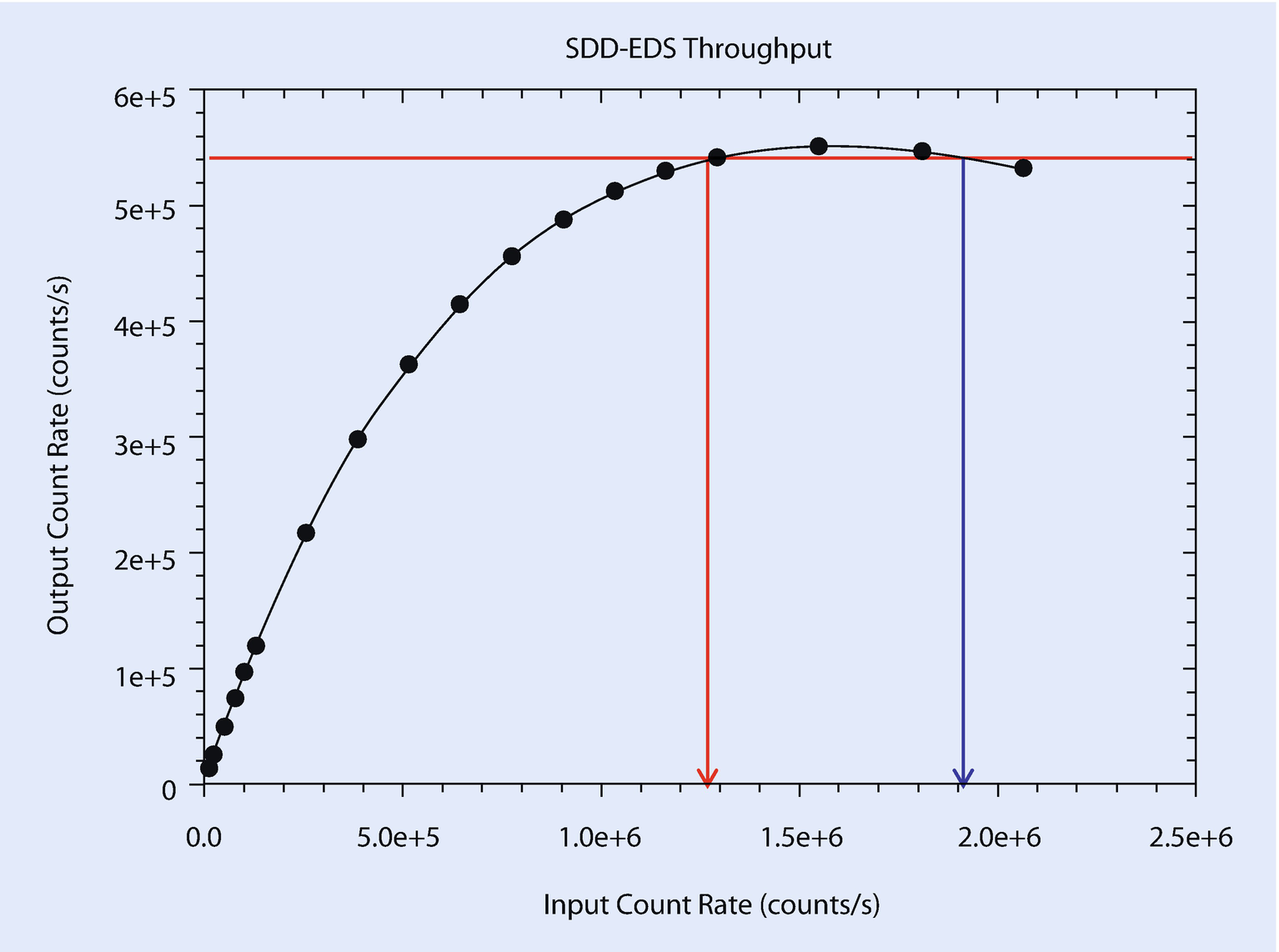

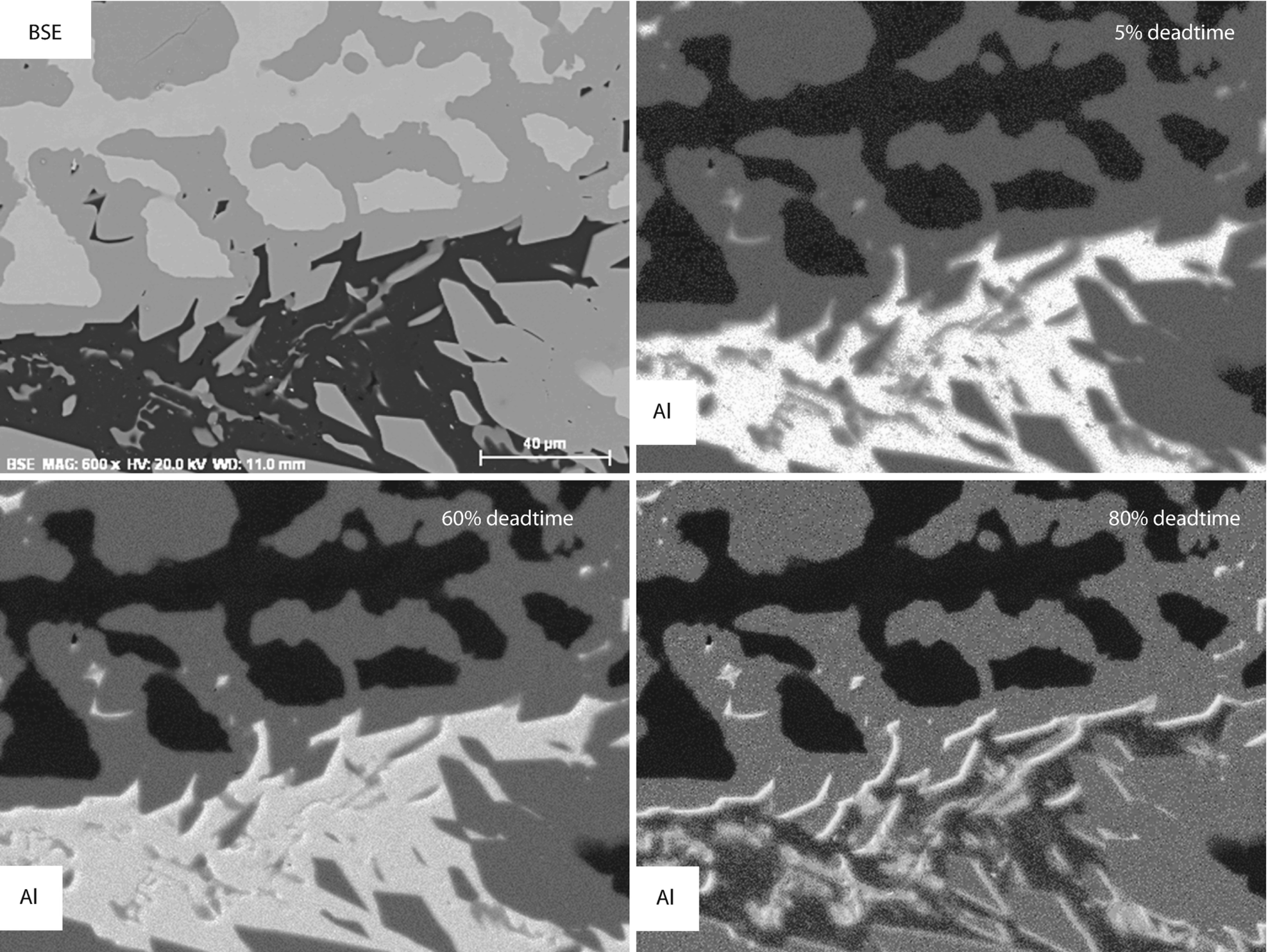

24.4.1 Choosing the EDS Dead-Time

Throughput of an SDD-EDS system consisting of four 10-mm2 detectors with the outputs summed at three different operating time constants

Example of XSI mapping at such high throughput level that count rate based artifacts appear: measured OCR vs. ICR response for an SDD-EDS, showing the same OCR for two different ICR values, which could represent different concentrations of a highly excited element

Al map in Raney nickel recorded at 5 %, 60 %, and 80 % dead-time; note changes in the high Al region at 80 % dead-time compared to 5 % dead-time

24.4.2 Choosing the Pixel Density

The size of the scanned area, the number of image pixels (n X, n Y) and the pixel dwell time, τ, are critical parameters that the analyst must choose when defining an XSI data collection. An estimate of the size of the lateral extent of the X-ray interaction volume, obtained either from the Kanaya–Okayama X-ray range or from Monte Carlo simulation, is also useful, especially for small-area, high-magnification mapping. Choosing the size of the scanned area (magnification) depends on the lateral extent of the specimen features that are the objective of the mapping measurement. As is the case with SEM imaging using BSEs and/or SEs, when large areas are being scanned (low magnification operation), the pixel size may be greater than the lateral extent of the X-ray source size, which is a convolution of the incident beam size and the interaction volume for X-ray production, so that much of the pixel area is effectively unsampled. In principle, the empty area of the pixel could be “filled in” by increasing the number of pixels to reduce the pixel size, but this would lead to extremely large XSI data structures that would require very long accumulation times. A practical upper limit for XSI mapping is typically 1024 × 1024 pixels, which for a spectrum of 4096 channels of 2 bytes intensity depth would produce an XSI of 8 Gbytes in the uncompressed RAW format. To reduce the mass storage as well as the subsequent processing time for quantitative compositional mapping calculations, the analyst may choose 512 × 512 or 256 × 256 pixel scan fields, especially when a small area is scanned (high magnification operation) leading to overlapping pixels. A pixel overlap of approximately 25 % serves to fill all space in the square pixels, but further oversampling provides no additional information, so that the analyst would be better served by lowering the magnification to cover more specimen area with the chosen pixel density, or alternatively, choose a lower pixel density.

24.4.3 Choosing the Pixel Dwell Time

Once the analyst has chosen the pixel density, the product of the number of pixels in a map and the pixel dwell time gives the total mapping time. The OCR of the EDS and the pixel dwell time determine the number of counts in the individual pixel spectra, which sets the ultimate limit on the compositional information that can be subsequently recovered from the XSI. The high throughput of SDD-EDS, especially when clusters of detectors are used, provides OCR of 105/s to 106/s, enabling various XSI imaging strategies determined by the number of counts in the individual pixel spectra.

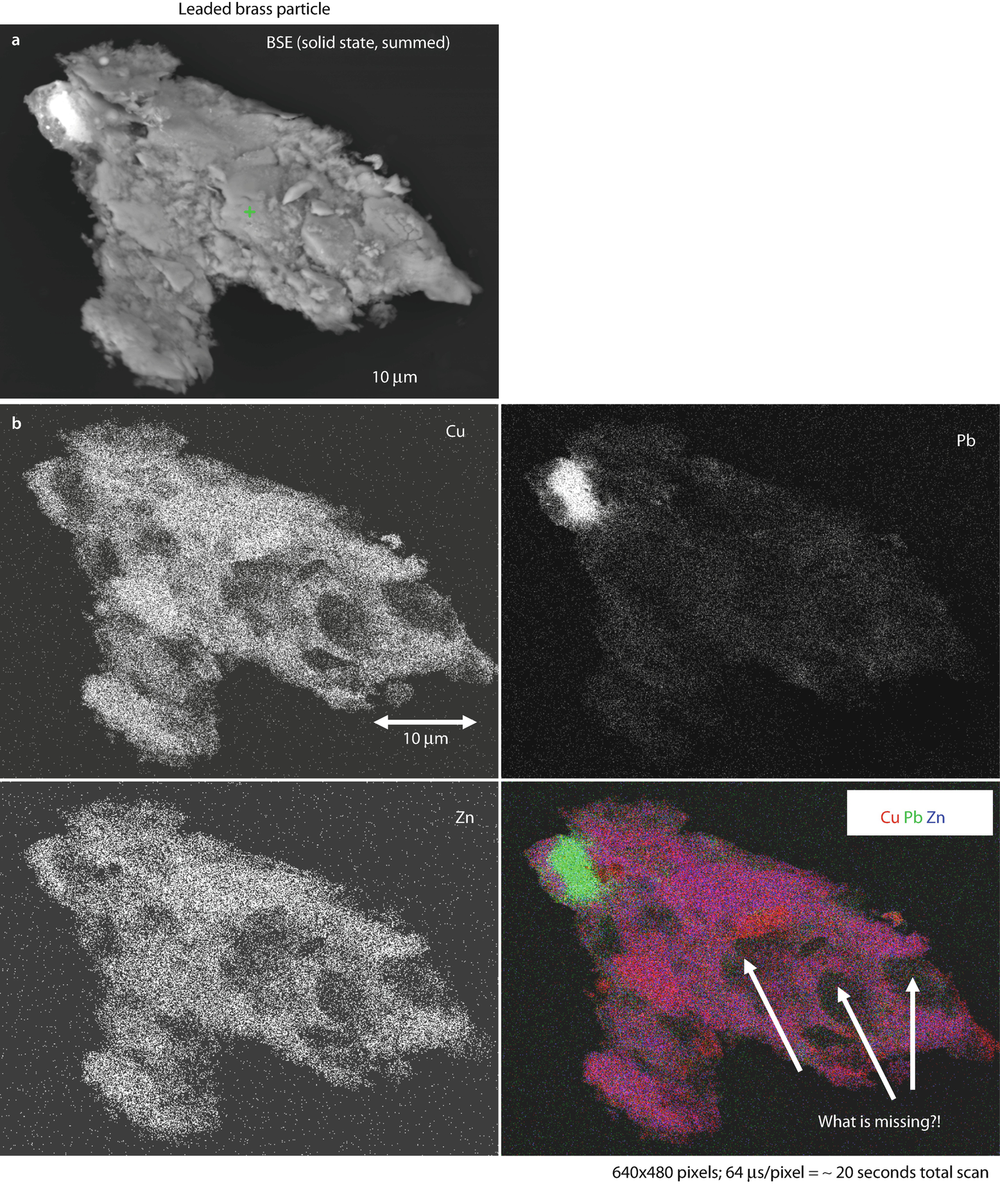

24.4.3.1 “Flash Mapping”

Leaded brass particle XSI: a SEM-BSE image; note bright inclusion; b XSI recorded with 640 × 480 pixels; 64 μs/pixel = ~ 20 s total scan and total intensity images for Pb, Cu and Zn with color overlay; note apparently missing regions of particle (dark)

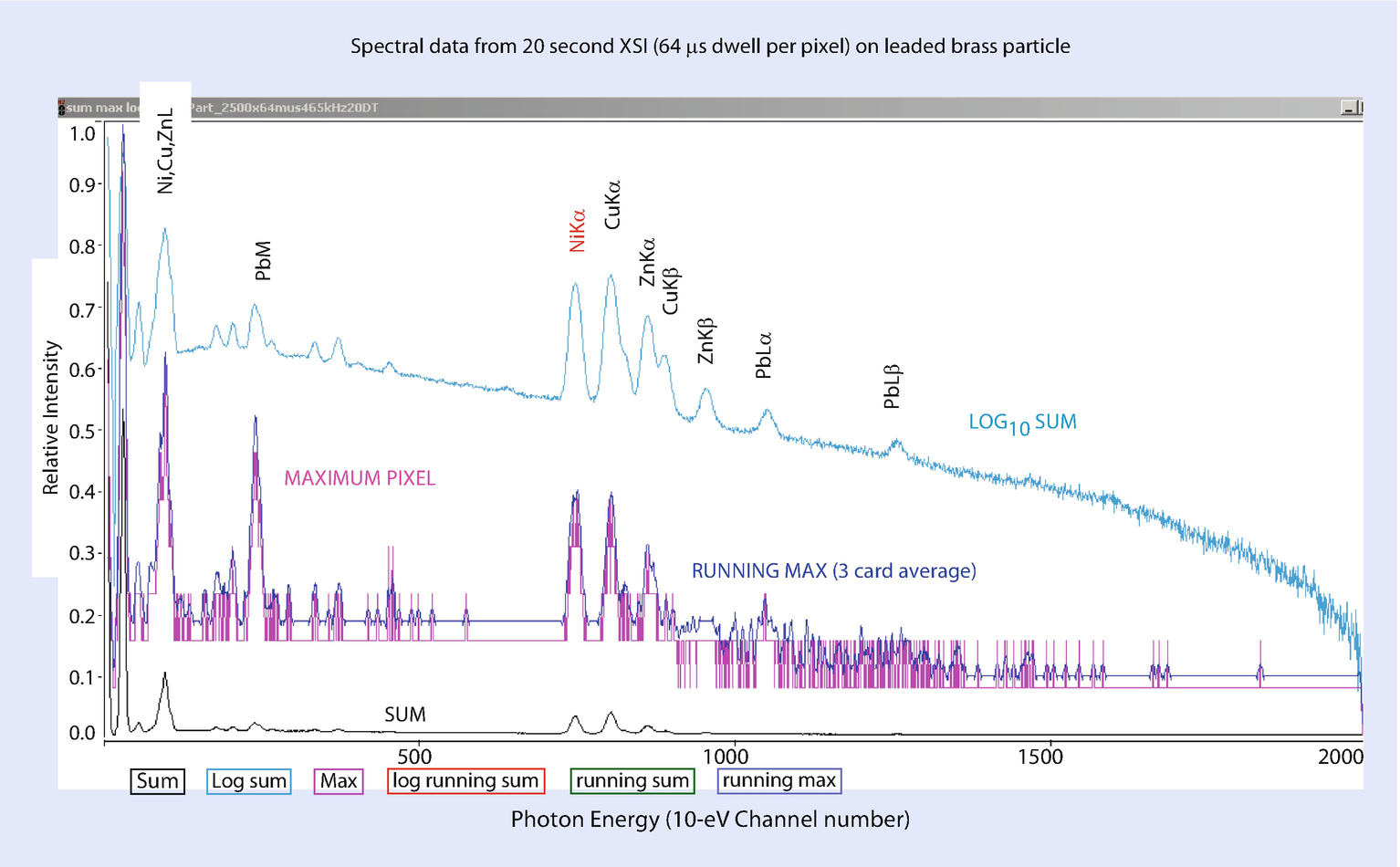

Leaded brass particle XSI: SUM spectrum, logarithm of the SUM spectrum, MAXIMUM PIXEL spectrum, and RUNNING MAXIMUM PIXEL spectrum (averaged over three consecutive energy “cards”); note unexpected Ni peak

Leaded brass particle XSI: a total intensity images for Cu, Zn, and Ni with color overlay showing Ni filling in empty areas seen in ◘ Fig. 24.25b; b direct comparison of SEM-BSE image and Cu, Ni, and Zn total intensity maps; the SEM-BSE image is insensitive to the compositional contrast between the Cu-Zn regions and the Ni-rich regions

24.4.3.2 High Count Mapping

The strategy for elemental mapping data collection depends on the nature of the problem to be solved: the most critical question is typically, “What concentration levels are of interest?” If minor and trace level constituents are not important, then short duration (60 s or less), low pixel density (256 × 256 or fewer) XSI maps with a high OCR will usually contain adequate counts, a minimum of approximately 50–500 counts per pixel spectrum, depending on the particular elements and overvoltage, to discern concentration-based contrast for major constituents, as shown in the examples in ◘ Figs. 24.25, 24.26, and 24.27. Of course, by accumulating more counts above this threshold, progressively lower concentration contrast details can be revealed for the major constituents. For problems involving minor and/or trace constituents, longer pixel dwell times are necessary to accumulate at least 500–5000 counts per pixel spectrum, and the beam current should be reduced to keep the dead-time generally below 10 % to minimize coincidence peaks. This dead-time condition can be relaxed if the coincidence peaks, which are only produced by high count rate parent peaks associated with major constituents, do not interfere with the minor/trace constituent peaks of interest.

Deep gray level mapping of Ni-Zr-V (with minor Ti, Cr, Mn, and Co) hydrogen-storage alloy (XSI conditions: 512 × 384 pixels, 8192 μs = 27 min; OCR 637 kHz = ~ 5200 counts/pixel spec): quantitative compositional maps with autoscaled gray level presentation for a major constituents and b minor constituents. Compositional values noted are derived from SUM spectra formed from pixel masks of the phases marked by arrows

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.