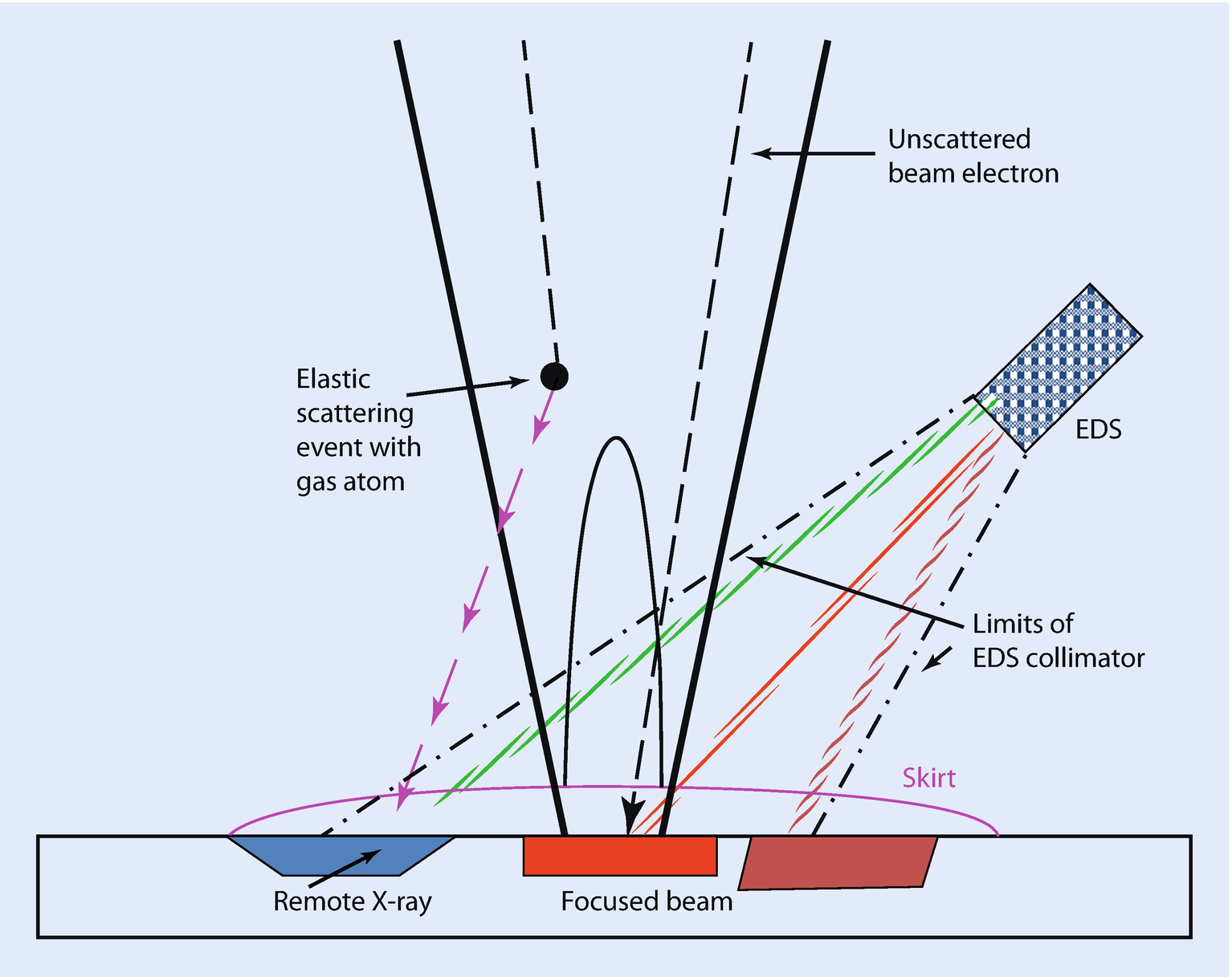

While X-ray analysis can be performed in the Variable Pressure Scanning Electron Microscope (VPSEM), it is not possible to perform uncompromised electron-excited X-ray microanalysis. The measured EDS spectrum is inevitably degraded by the effects of electron scattering with the atoms of the environmental gas in the specimen chamber before the beam reaches the specimen. The spectrum is always a composite of X-rays generated by the unscattered electrons that remain in the focused beam and strike the intended target mixed with X-rays generated by the gas-scattered electrons that land elsewhere, micrometers to millimeters from the microscopic target of interest.

It is critical to understand how severely the measured spectrum is compromised, what strategies can be followed to minimize these effects, and what “workarounds” can be applied in special circumstances to solve practical problems. The impact of gas-scattered electrons on the legitimacy of the analysis depends on the exact circumstances of the VPSEM conditions (beam energy, gas species, path length through the gas) and the characteristics of the specimen and its surroundings. Gas scattering effects increase in significance as the constituent(s) of interest range in concentration from major (concentration C > 0.1 mass fraction) to minor (0.01 ≤ C ≤ 0.1) to trace (C < 0.01).

25.1 Gas Scattering Effects in the VPSEM

Schematic diagram of gas scattering in a VPSEM

R s = skirt radius (m)

Z = atomic number of the gas

E = beam energy (keV)

p = pressure (Pa)

T = temperature (K)

L = path length in gas (m) (GPL)

Radial dimension of gas scattering skirt as a function of gas path length at various pressures for O2 and E 0 = 20 keV

Selection of VPSEM gas parameters in DTSA-II for simulation

Portion of the electron scattering table for VPSEM simulation. Note the unscattered fraction of the 20 keV beam, 0.701 (100 Pa, 5-mm gas path length, oxygen). The full table extends to 1000 μm

Ring | Inner radius, μm | Outer radius, μm | Ring area, μm2 | Electron count | Electron fraction | Cumulative, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Undeflected | – | – | – | 701 | 0.701 | – |

1 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 19.6 | 755 | 0.755 | 75.5 |

2 | 2.5 | 5.0 | 58.9 | 23 | 0.023 | 77.8 |

3 | 5.0 | 7.5 | 98.2 | 11 | 0.011 | 78.9 |

4 | 7.5 | 10.0 | 137.4 | 10 | 0.010 | 79. 9 |

5 | 10.0 | 12.5 | 176.7 | 7 | 0.007 | 80.6 |

6 | 12.5 | 15.0 | 216.0 | 6 | 0.006 | 81.2 |

7 | 15.0 | 17.5 | 255.3 | 9 | 0.009 | 82.1 |

8 | 17.5 | 20.0 | 294.5 | 10 | 0.010 | 83.1 |

9 | 20.0 | 22.5 | 333.8 | 4 | 0.004 | 83.5 |

10 | 22.5 | 25.0 | 373.1 | 3i | 0.003 | 83.8 |

11 | 25.0 | 27.5 | 412.3 | 6 | 0.006 | 84.4 |

12 | 27.5 | 30.0 | 451.6 | 4 | 0.004 | 84.8 |

13 | 30.0 | 32.5 | 490.9 | 6 | 0.006 | 85.4 |

14 | 32.5 | 35.0 | 530.1 | 2 | 0.002 | 85.6 |

15 | 35.0 | 37.5 | 569.4 | 2 | 0.002 | 85.8 |

16 | 37.5 | 40.0 | 608.7 | 3 | 0.003 | 86.1 |

17 | 40.0 | 42.5 | 648.0 | 4 | 0.004 | 86.5 |

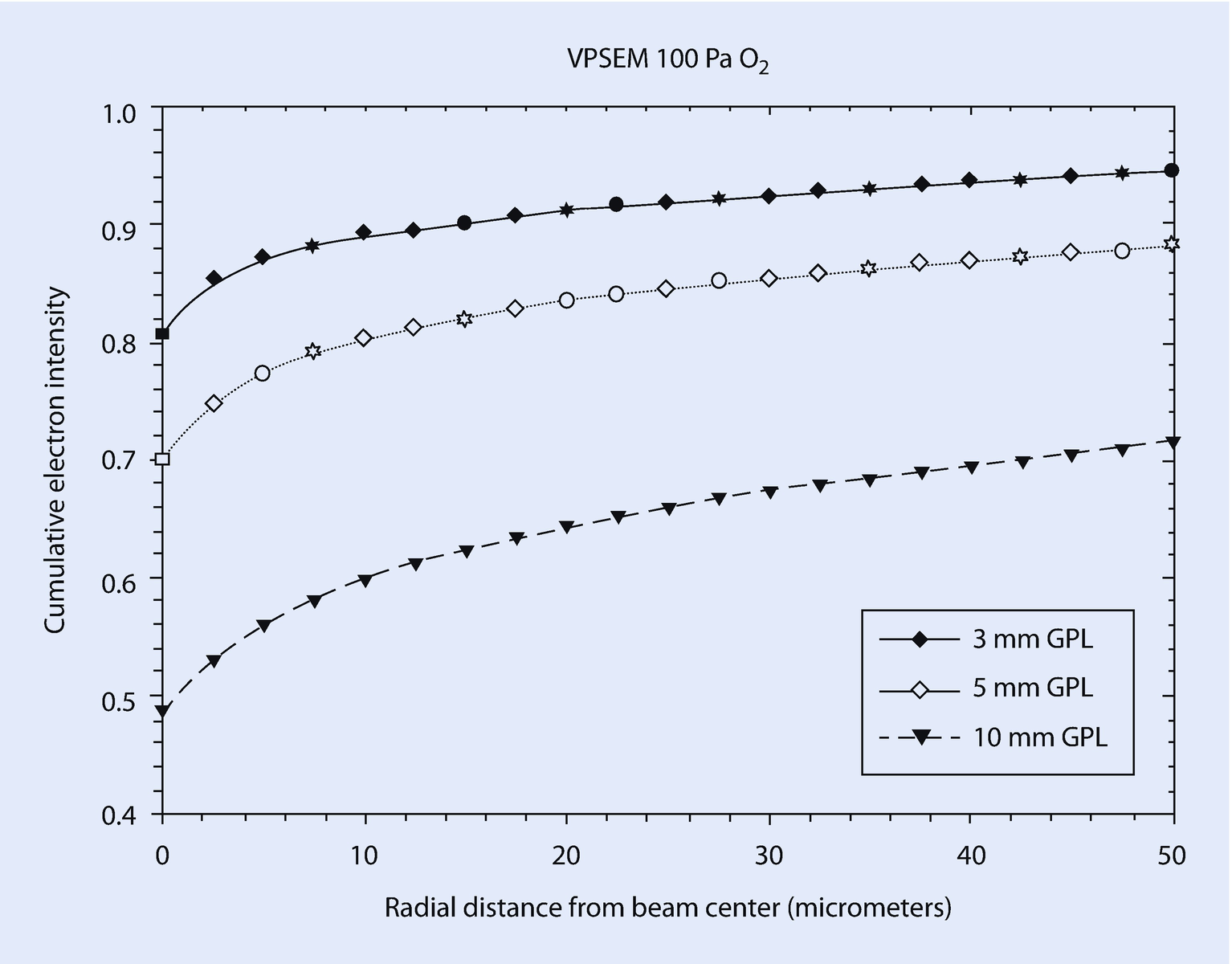

DTSA-II Monte Carlo calculation of gas scattering in a VPSEM: E 0 = 20 keV; oxygen; 100 Pa; 3-, 5-, and 10-mm gas path lengths (GPL) to a radial distance of 50 μm

DTSA-II Monte Carlo calculation of gas scattering in a VPSEM: E 0 = 20 keV; oxygen; 100 Pa; 3-, 5-, and 10-mm gas path lengths to a radial distance of 1000 μm

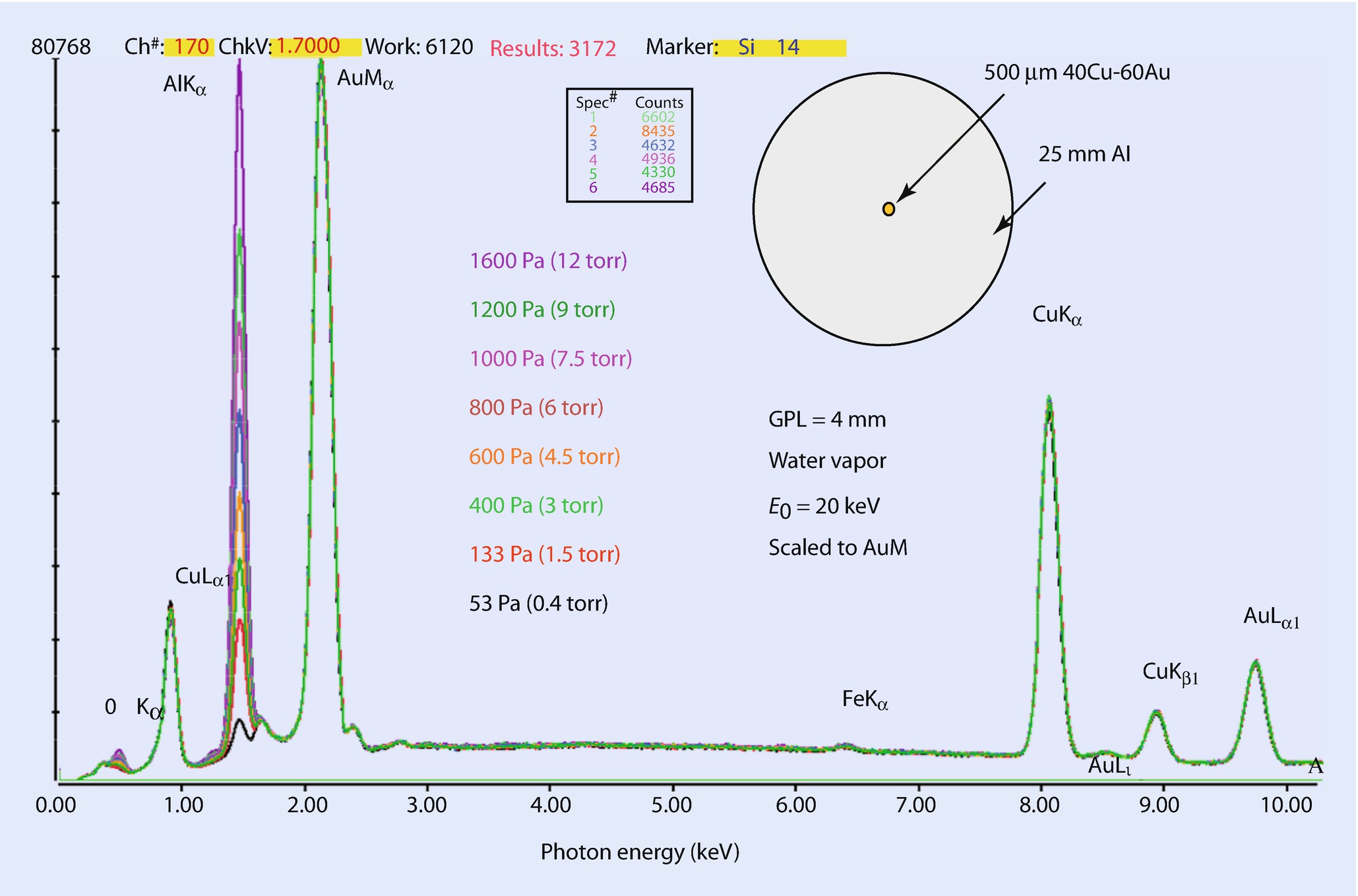

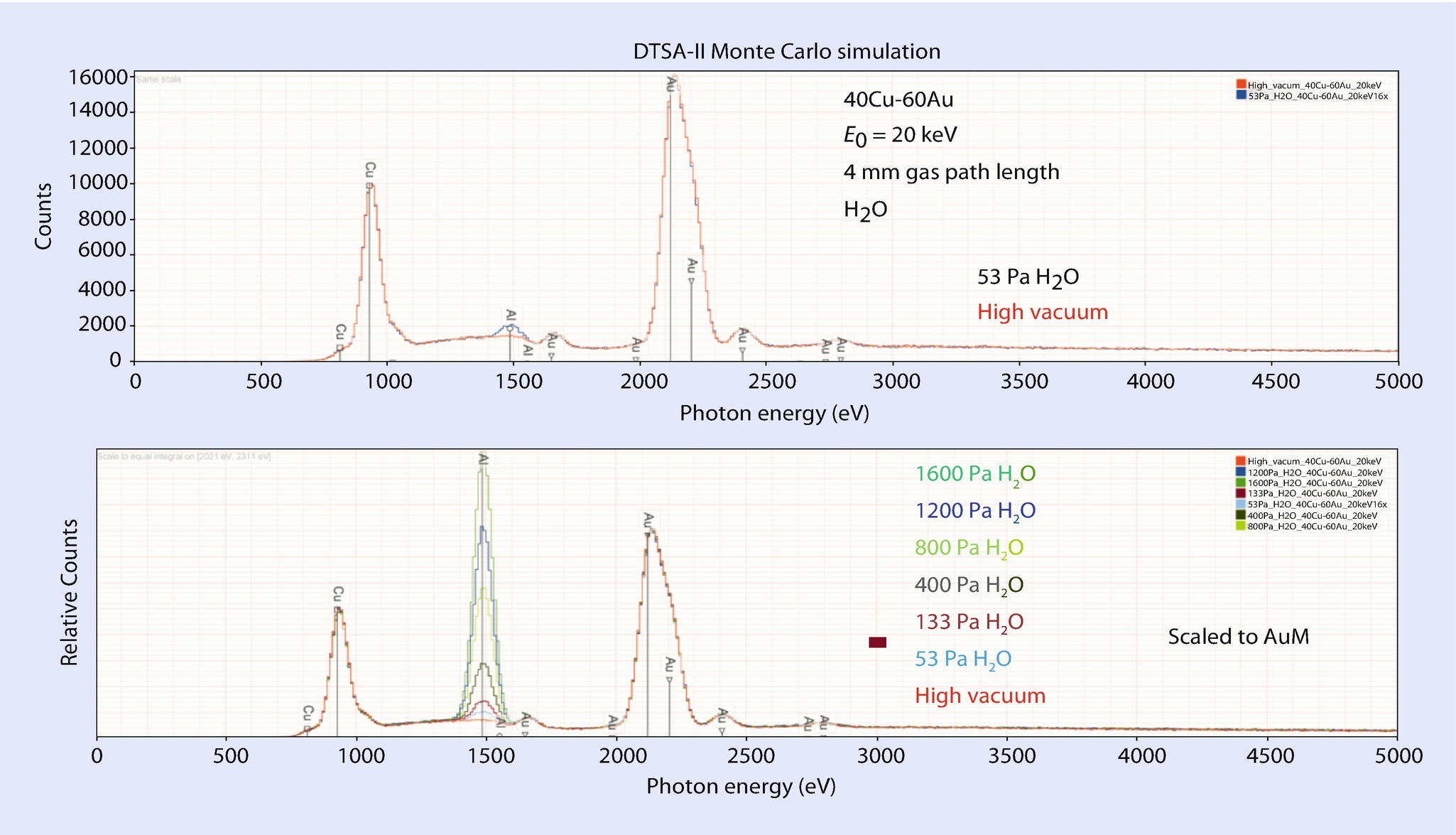

EDS spectra measured with the beam placed in the center of a 500 μm diameter wire of 40 wt % Cu–60 wt %Au surrounded by a 2.5-cm-diameter Al disk; E 0 = 20 keV; gas path length = 4 mm; oxygen at various pressures

DTSA-II Monte Carlo simulations of the specimen and gas scattering conditions of ◘ Fig. 25.6. Upper plot: high vacuum and 53 Pa (4 mm GPL, H2O). Lower plot: high vacuum and various pressures from 53 Pa to 1600 Pa

25.1.1 Why Doesn’t the EDS Collimator Exclude the Remote Skirt X-Rays?

Schematic diagram showing the acceptance area of the EDS collimator

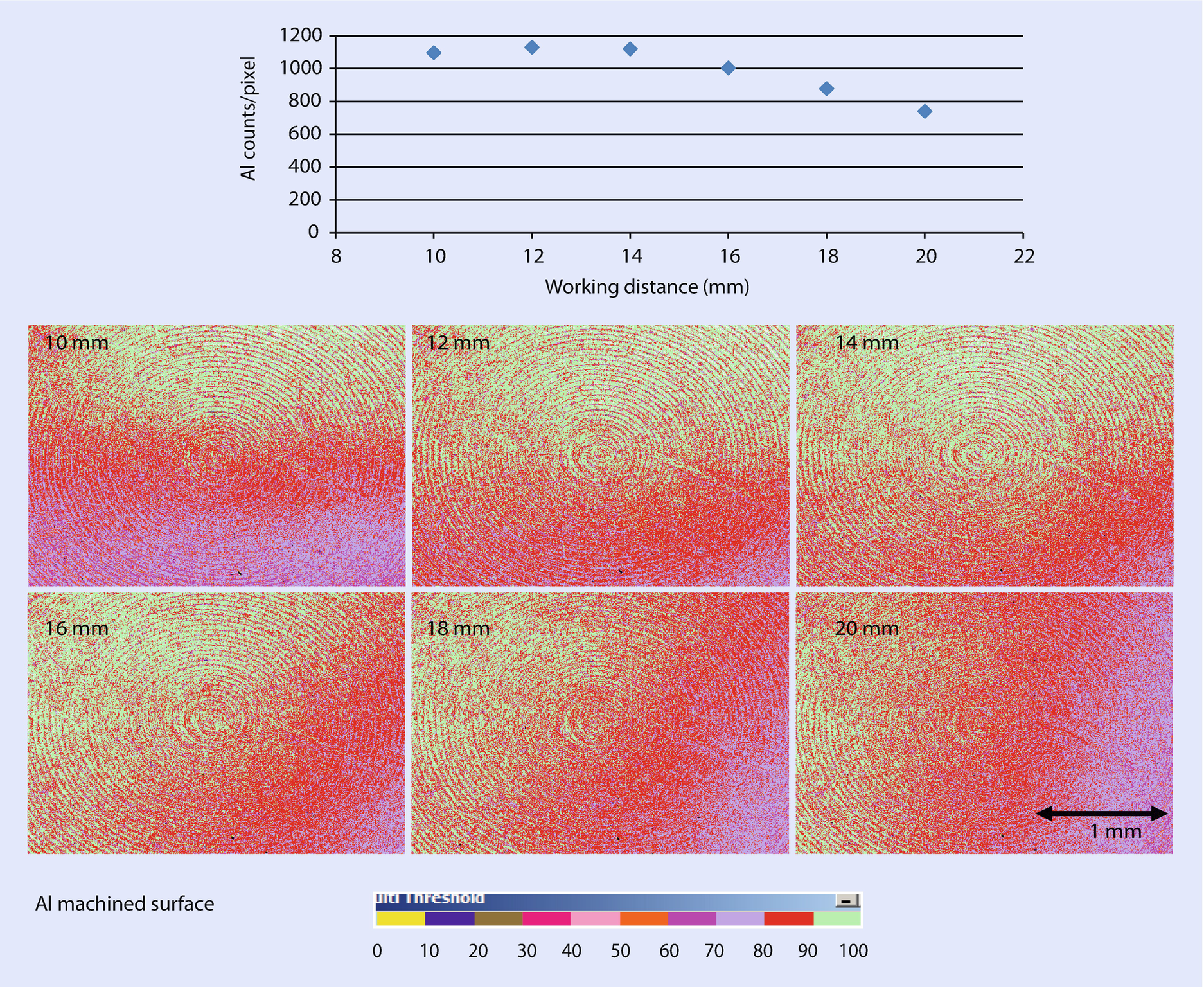

Collimator acceptance volume as determined by mapping an Al disk at various working distances (10–20 mm) at the widest scanned field (i.e., lowest magnification); the plot shows the intensity measured at the center of the scan field as a function of working distance

25.1.2 Other Artifacts Observed in VPSEM X-Ray Spectrometry

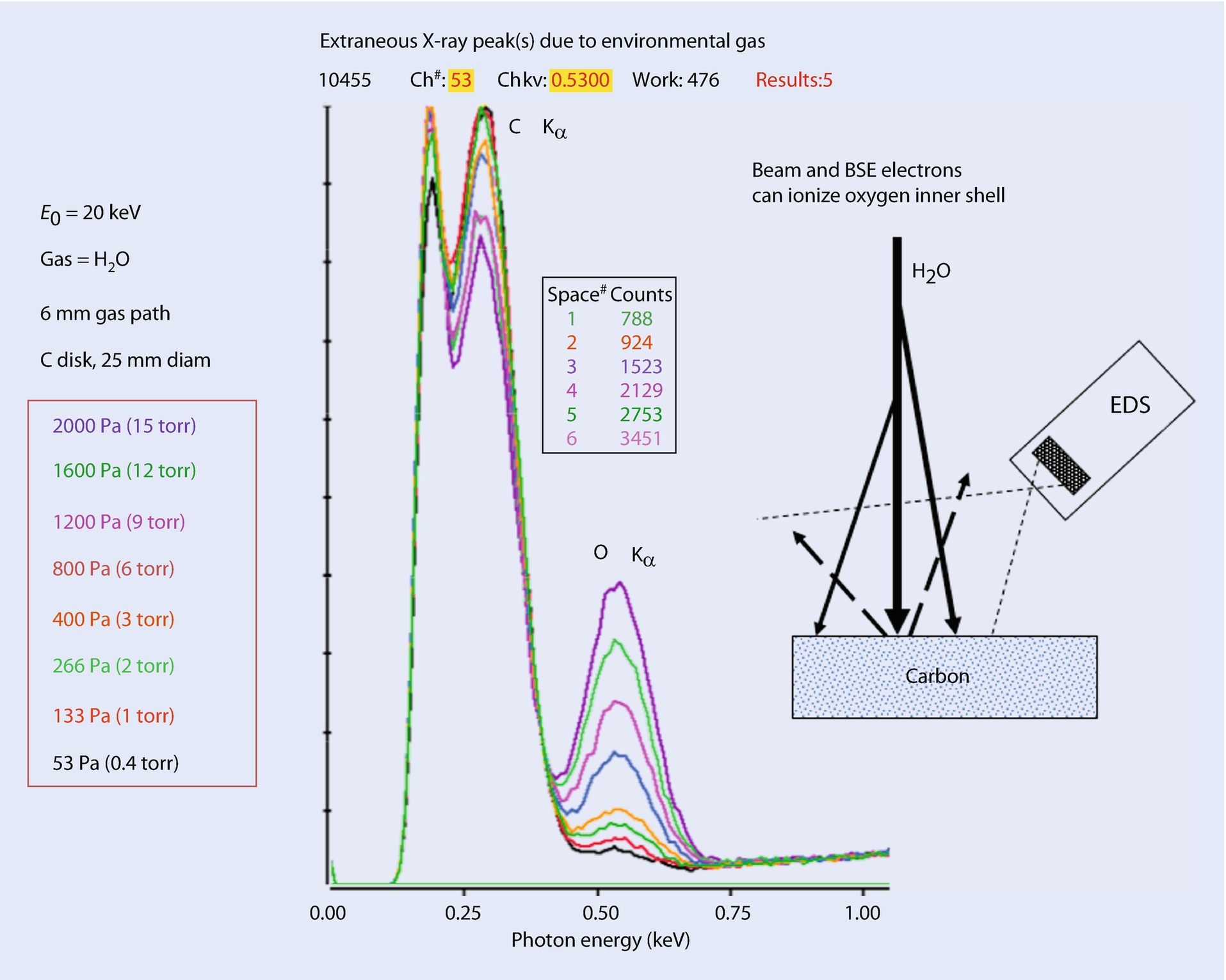

Generation of O K X-rays from the environmental gas as a function of chamber pressure

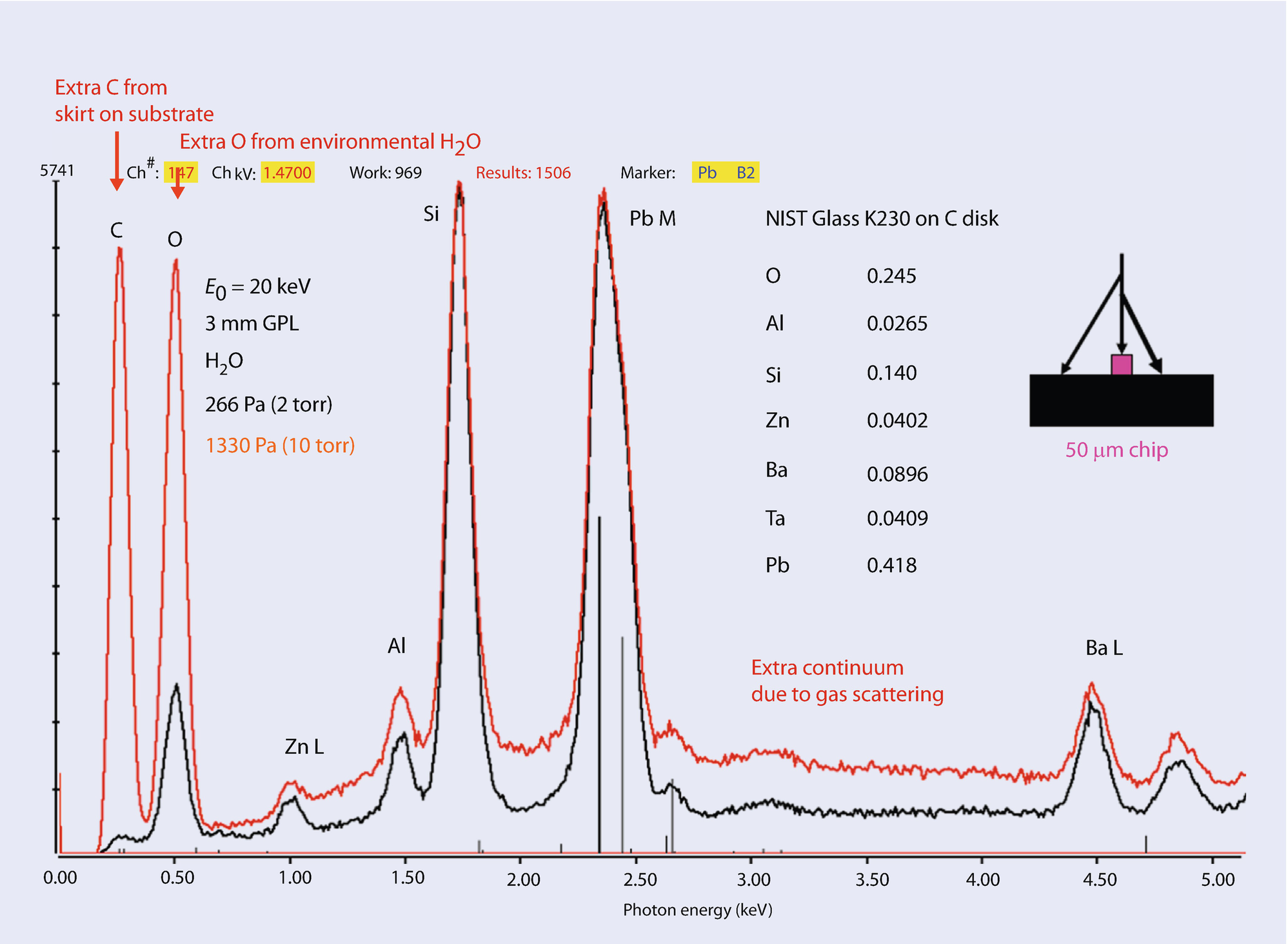

Modification of the measured X-ray spectrum by gas scattering, including in-growth of the O K peak from contributions of the environmental gas as well as increased background due to increased bremsstrahlung created by the gas scattering

Absorption of X-rays by the environmental gas (O2) (40-mm source to EDS)

Element/X-ray | I/I0 (2500 Pa) | I/I0 (100 Pa) | I/I0 (10 Pa) |

|---|---|---|---|

F K (0.677 keV) | 0.194 | 0.940 | 0.994 |

NaK (1.041 keV) | 0.572 | 0.979 | 0.998 |

AlK (1.487 keV) | 0.805 | 0.992 | 0.9992 |

SiK (1.740 keV) | 0.868 | 0.995 | 0.9995 |

S K (2.307 keV) | 0.939 | 0.998 | 0.9998 |

ClK (2.622 keV) | 0.957 | 0.998 | 0.9998 |

K K (3.312 keV) | 0.986 | 0.999 | 0.9999 |

CaK (3.690 keV) | 0.990 | 0.9996 | 0.9999 |

25.2 What Can Be Done To Minimize gas Scattering in VPSEM?

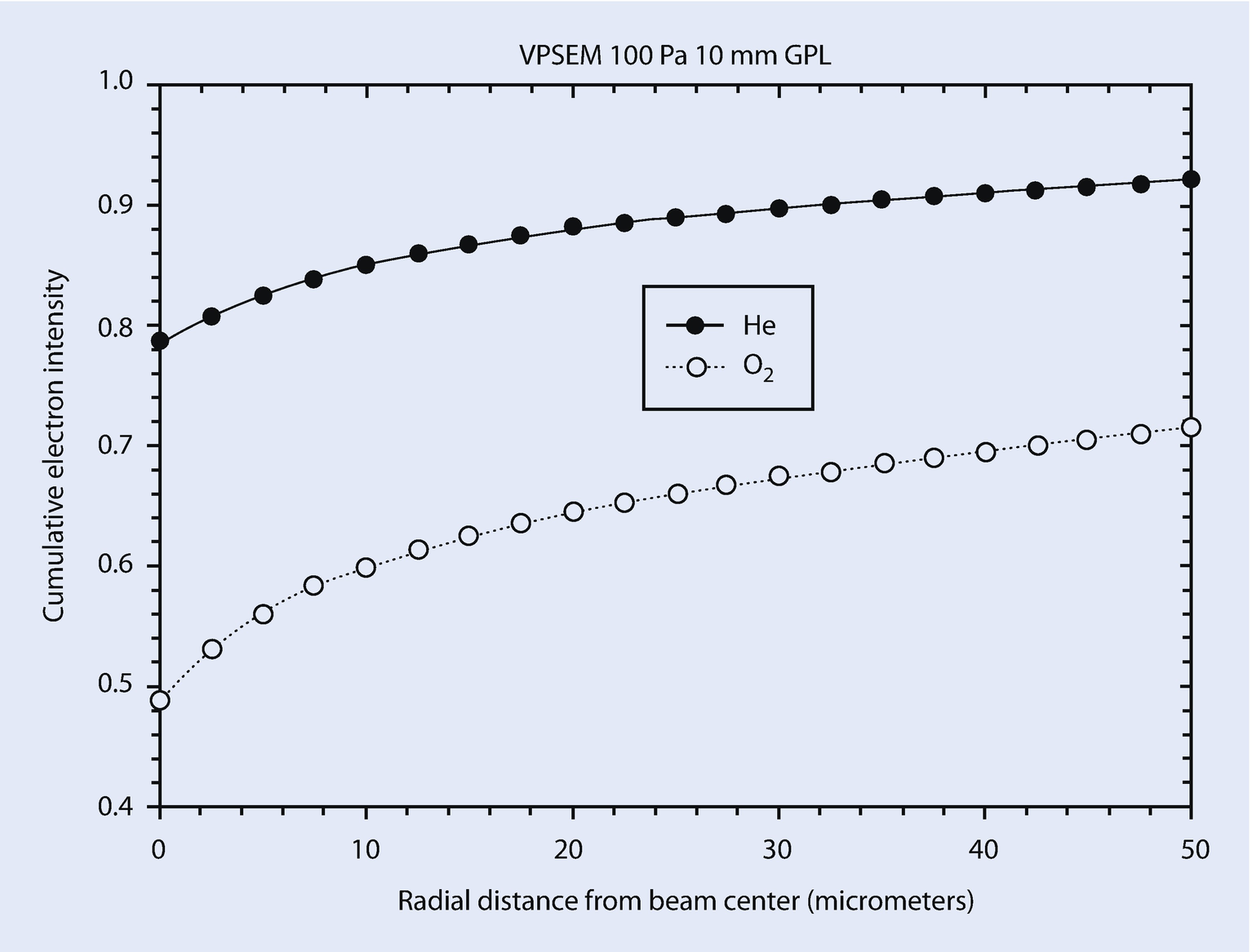

- 1.Z, atomic number of the scattering gas: By lowering the atomic number of the gas, the skirt radius is reduced. This effect is illustrated in ◘ Fig. 25.12, which is derived from DTSA-II Monte Carlo simulations comparing the skirt radius for He and O2 for a 10-mm gas path length and 100-Pa gas pressure with a beam energy E 0 = 20 keV.

Fig. 25.12

Fig. 25.12Comparison of the scattering skirt for He and O2

- 2.

E, beam energy (keV). Operating at the highest possible beam energy reduces the gas scattering skirt.

- 3.

p, the gas pressure (Pa): Operating with the lowest possible gas pressure minimizes the gas scattering skirt

- 4.

T, the sample chamber temperature (K): The scattering skirt is reduced by operating at the lowest possible temperature.

- 5.

L, the gas path length (m). The shorter the gas path length, the smaller the gas scattering skirt, as shown in ◘ Fig. 25.4, where the skirt is compared for gas path lengths of 3 mm, 5 mm, and 10 mm. Note that the gas path length appears in Eq. (25.1) with a 3/2 power, so that the skirt radius is more sensitive to this parameter than the other parameters in Eq. (25.1). A modification to the vacuum system of the VPSEM that minimizes the gas path length consists of using a small diameter tube to extend the high vacuum of the electron column into the sample chamber.

25.2.1 Workarounds To Solve Practical Problems

Major constituent: concentration C > 0.1 mass fraction

Minor constituent: 0.01 ≤ C ≤ 0.1

Trace constituent: C < 0.01

Depending on the exact nature of the specimen, gas scattering will almost always introduce spectral artifacts at the trace and minor constituent levels, and in severe cases artifacts will appear at the level of apparent major constituents.

25.2.2 Favorable Sample Characteristics

Given that the LVSEM operating conditions have been selected to minimize the gas scattering skirt, what specimen types are most likely to yield useful microanalysis results? If most of the gas scattering skirt falls on background material that contains an element or elements that are different from the elements of the target and of no interest, then by following a measurement protocol to identify the extraneous elements, the measured spectrum can still have value for identifying the elements within the target area, always recognizing that the target is being excited by the focused beam and the skirt.

25.2.2.1 Particle Analysis

- 1.

When particles are collected on a smooth (i.e., not tortuous path) medium such as a porous polycarbonate filter, the loaded filter can be studied directly in the VPSEM with no preparation other than to attach a portion of the filter to a support stub. Prior to attempting X-ray measurements of individual particles, the X-ray spectrum of the filter material should be measured under the VPSEM operating conditions as the first stage of determining the analytical blank (that is, the spectral contributions of all the materials involved in the preparation except the specimen itself). In addition to revealing the elemental constituents of the filter, this blank spectrum will also reveal the contribution of the environmental gas to the spectrum.

- 2.

When particles are to be transferred from the collection medium, such as a tortuous path filter, or simply obtained from a loose mass in a container, the choice of the sample substrate is the first question to resolve. Conceding that VPSEM operation will lead to significant remote scattering that will excite the substrate, the sample substrate should be chosen to consist of an element that is not of interest in the analysis of individual particles. Carbon is a typical choice for the substrate material, but if the analysis of carbon in the particles is important, then an alternative material such as beryllium (but beware of the health hazards of beryllium and its oxide) or boron can be selected. If certain higher atomic number elements can be safely ignored in the analysis, then additional materials may be suitable for substrates, such as aluminum, silicon, germanium, or gold (often as a thick film evaporated on silicon). Again, whatever the choice of substrate, the X-ray spectrum of the bare substrate should be measured to establish the analytical blank prior to analyzing particles on that substrate.

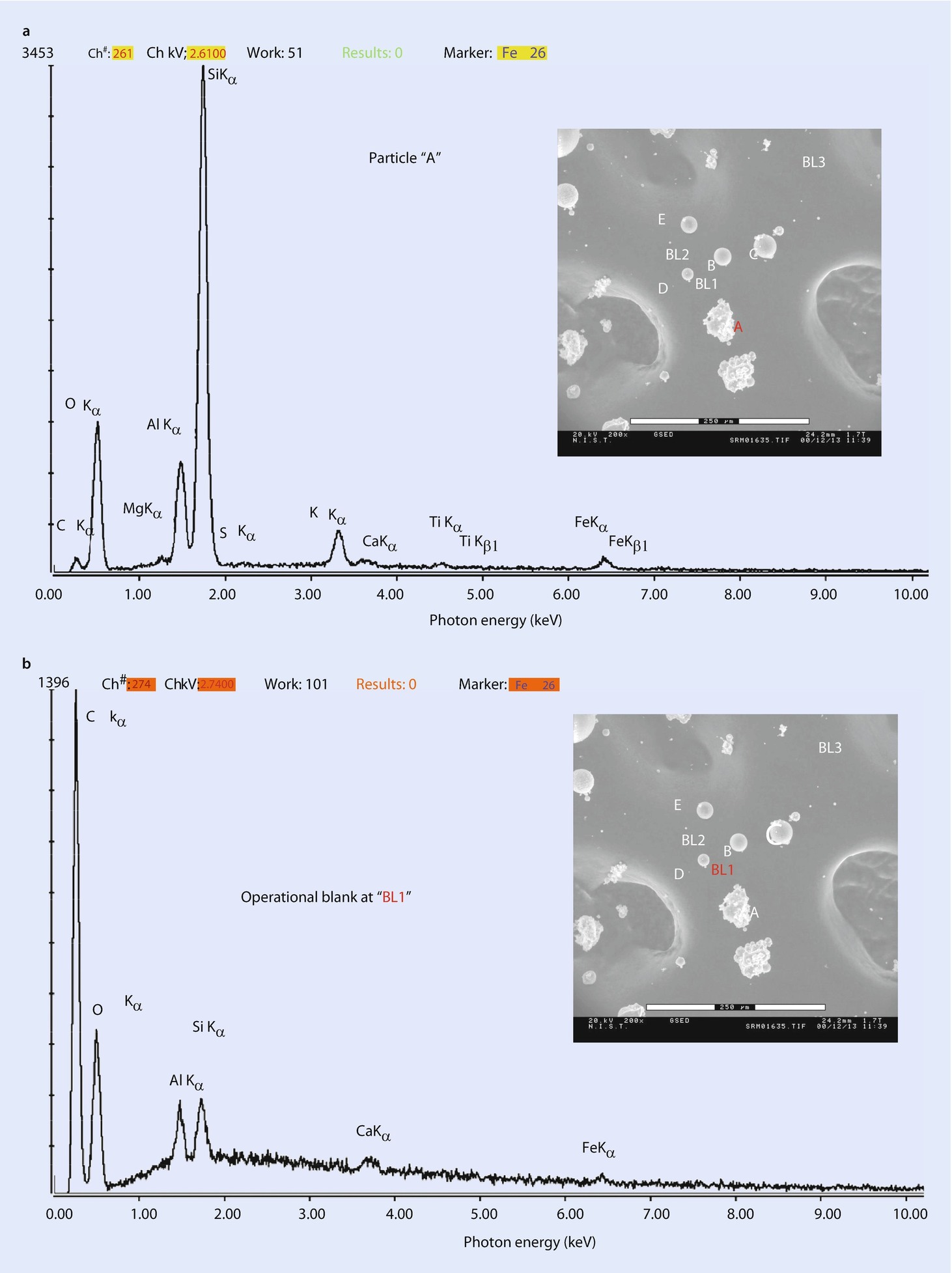

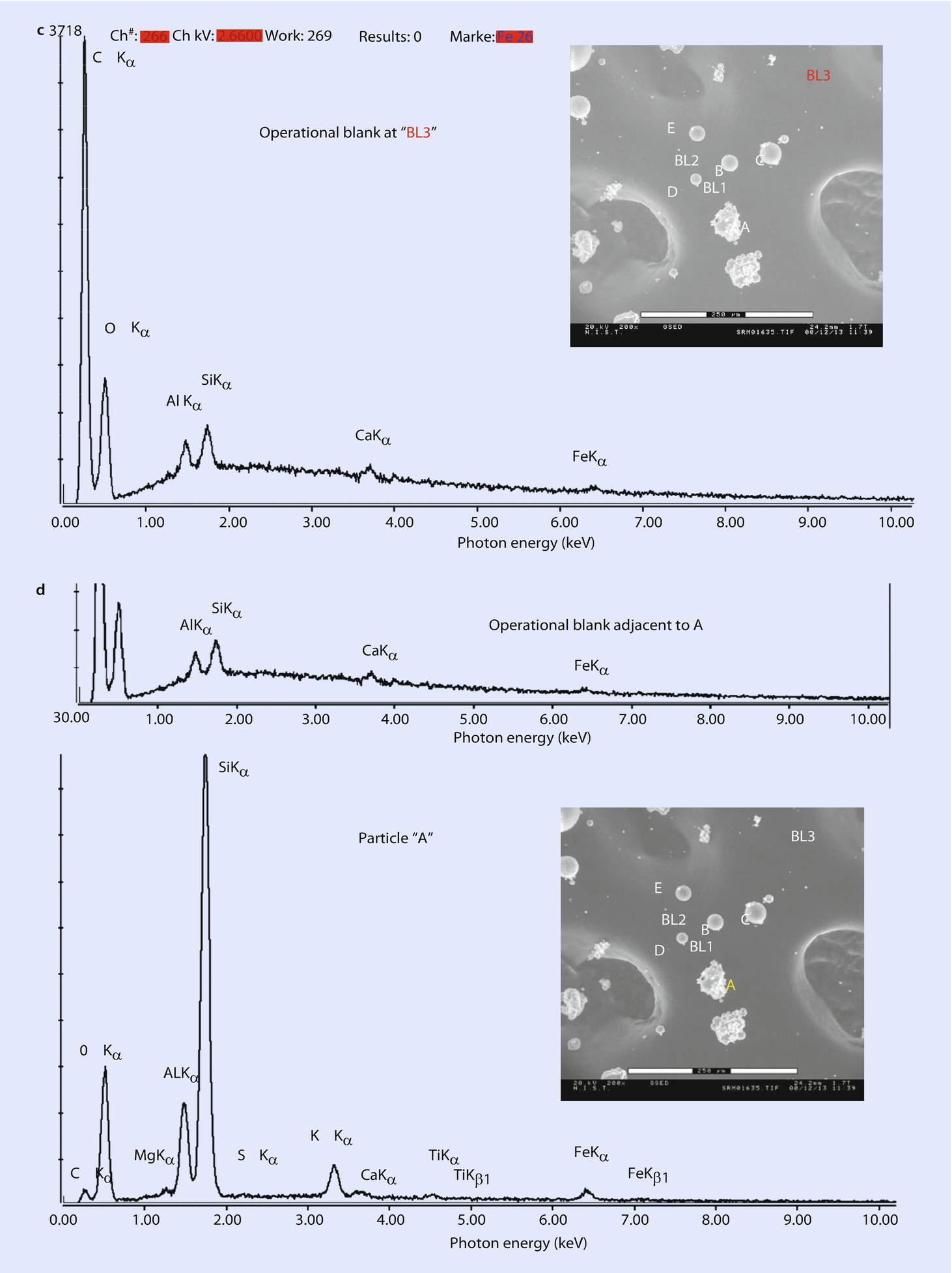

a VPSEM image of a cluster of particles and an EDS X-ray spectrum measured with the beam placed on one of them, particle “A.” b EDS X-ray spectrum measured with the beam placed on the substrate at location BL1 so that only the beam skirt excites the particles. c EDS X-ray spectrum measured with the beam placed on the substrate at location BL3 so that only the beam skirt excites the particles. d Use of analytical blank to aid interpretation of the EDS spectrum of Particle “A.” e Use of analytical blank to aid interpretation of the EDS spectrum of Particle “A”

25.2.3 Unfavorable Sample Characteristics

SEM-BSE image of Raney nickel in a VPSEM

a EDS spectra obtained at locations “D”, “I,” and “B.” E 0 = 20 keV; water vapor; 50 Pa, 6-mm gas path length. b EDS spectra obtained at locations “D,” “I,” and “B.” E 0 = 20 keV; water vapor; 665 Pa, 6-mm gas path length

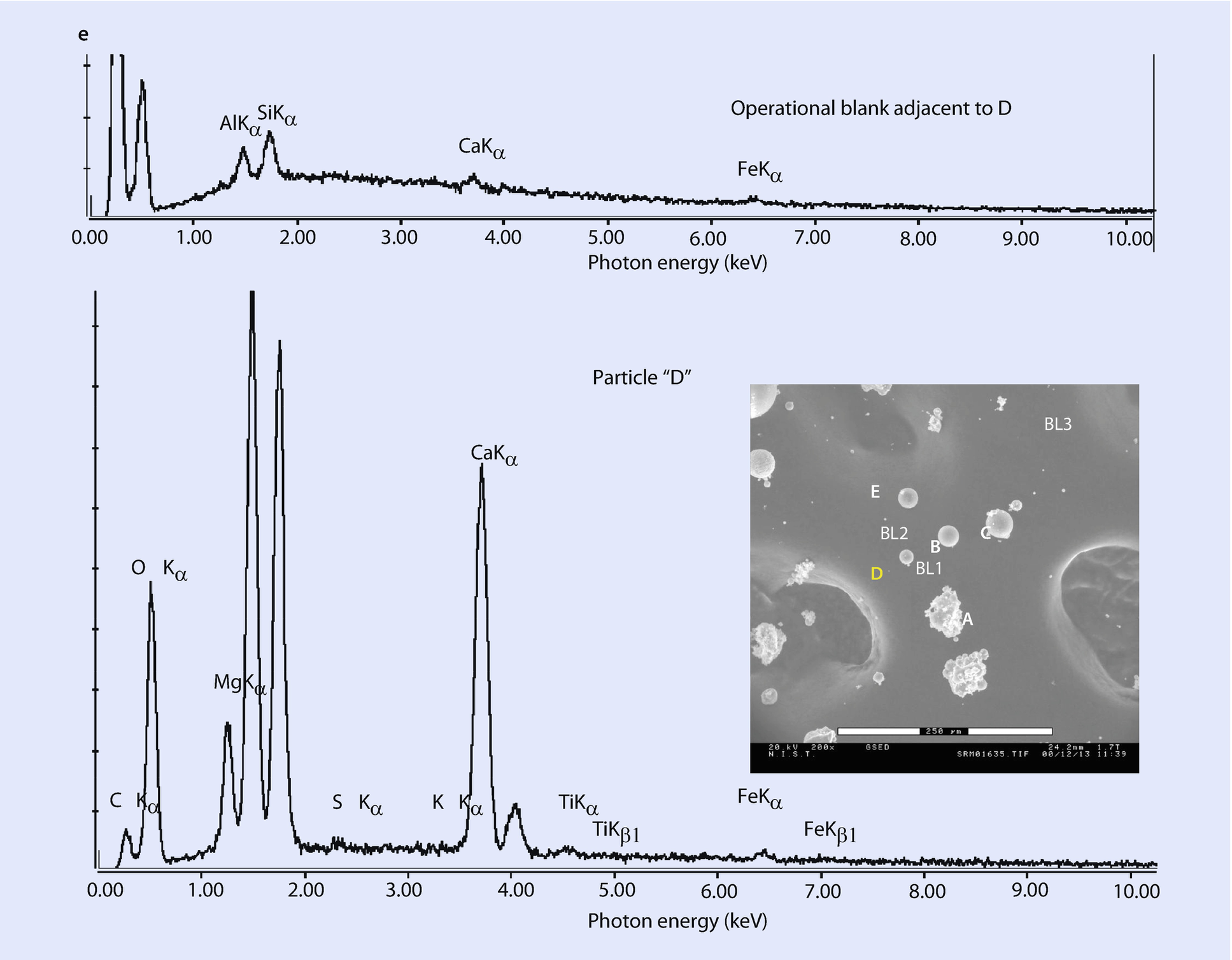

a Elemental intensity map for Al K-L2 at various pressures (E 0 = 20 keV, water vapor and 6-mm gas path length). b Elemental intensity map for NiKα at various pressures (E 0 = 20 keV, water vapor and 6-mm gas path length)

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.