27.1 Case Study: Characterization of a Hard-Facing Alloy Bearing Surface

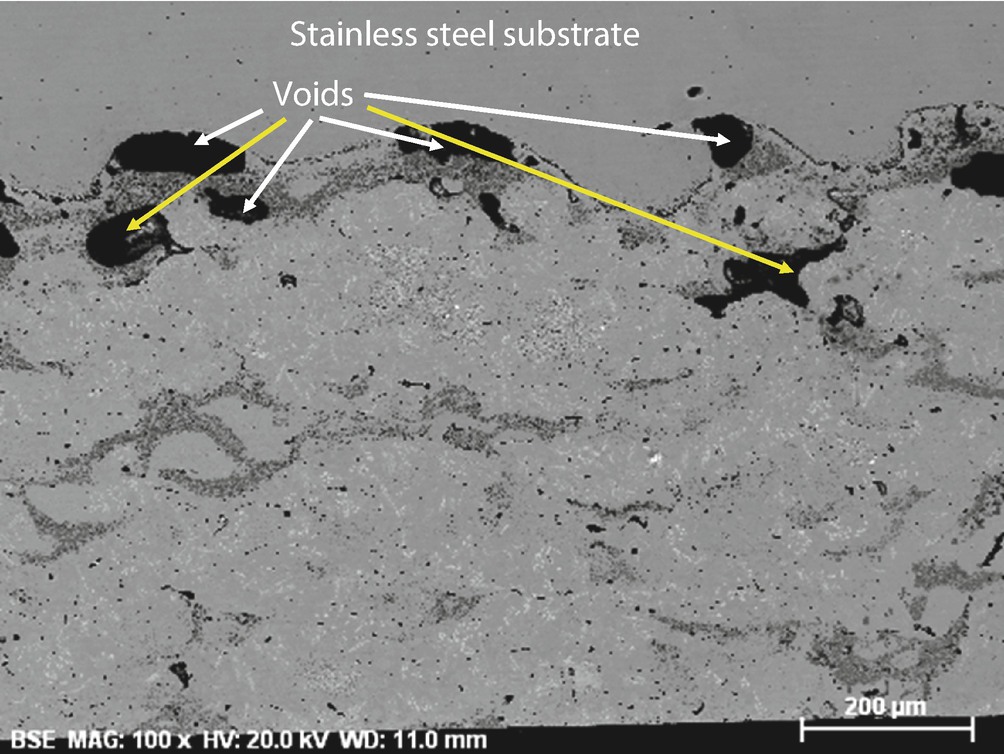

Background: As part of a study into the in-service failure of the bearing surface of a large water pump, characterization was requested of the hard-facing alloy, which was observed to have separated from the stainless steel substrate, causing the failure.

SEM-BSE image of the cross-section of a hard-facing alloy deposited on a stainless steel substrate. Note the voids at the interface between the hard-facing alloy and the stainless substrate (white arrows), as well as a smaller population of voids entirely within the hard-facing alloy (green arrows)

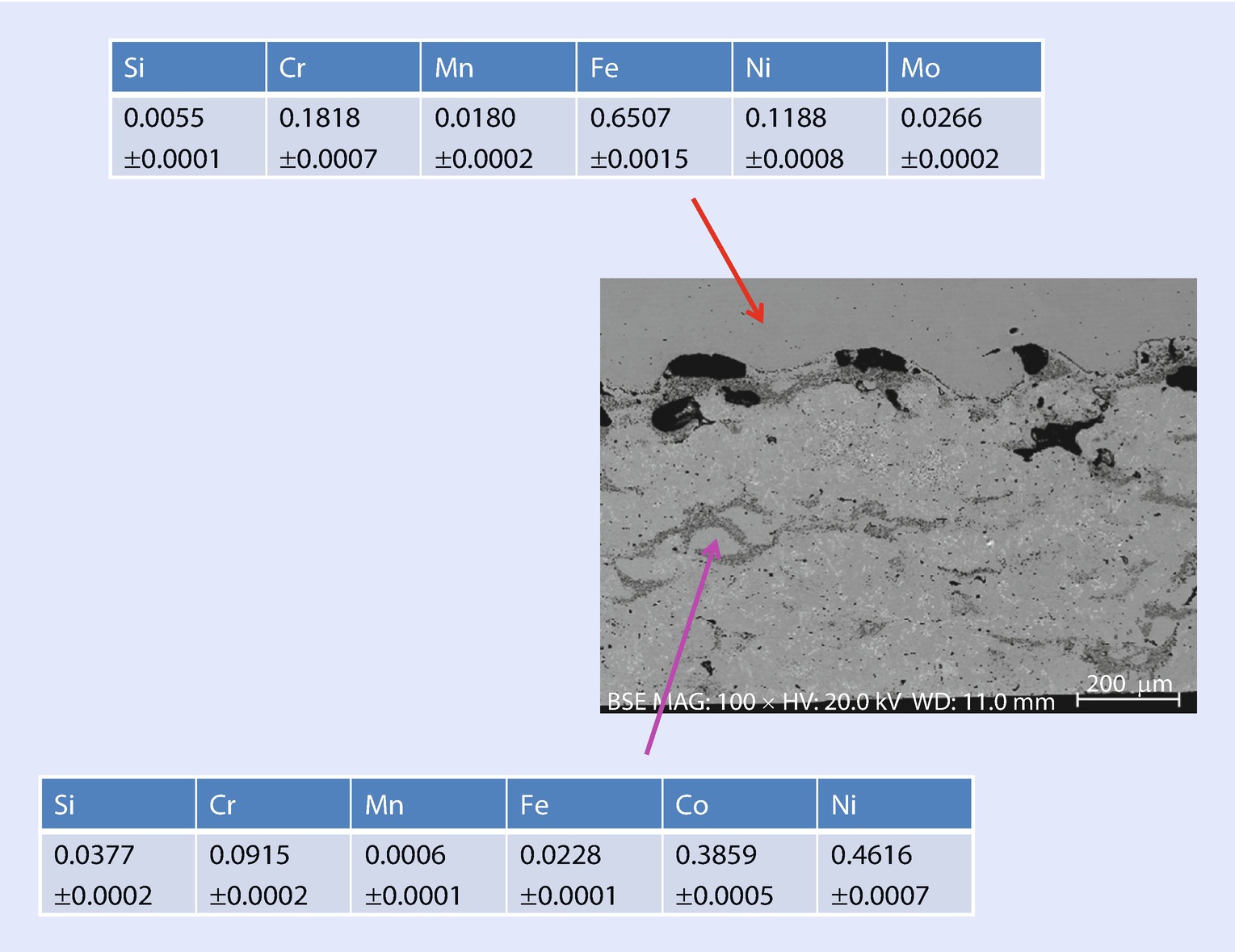

SEM-BSE image showing locations of SEM-EDS analyses with NIST DTSA-II

Elemental mapping, with color overlay: Ni = red; Cr = green; Co = blue

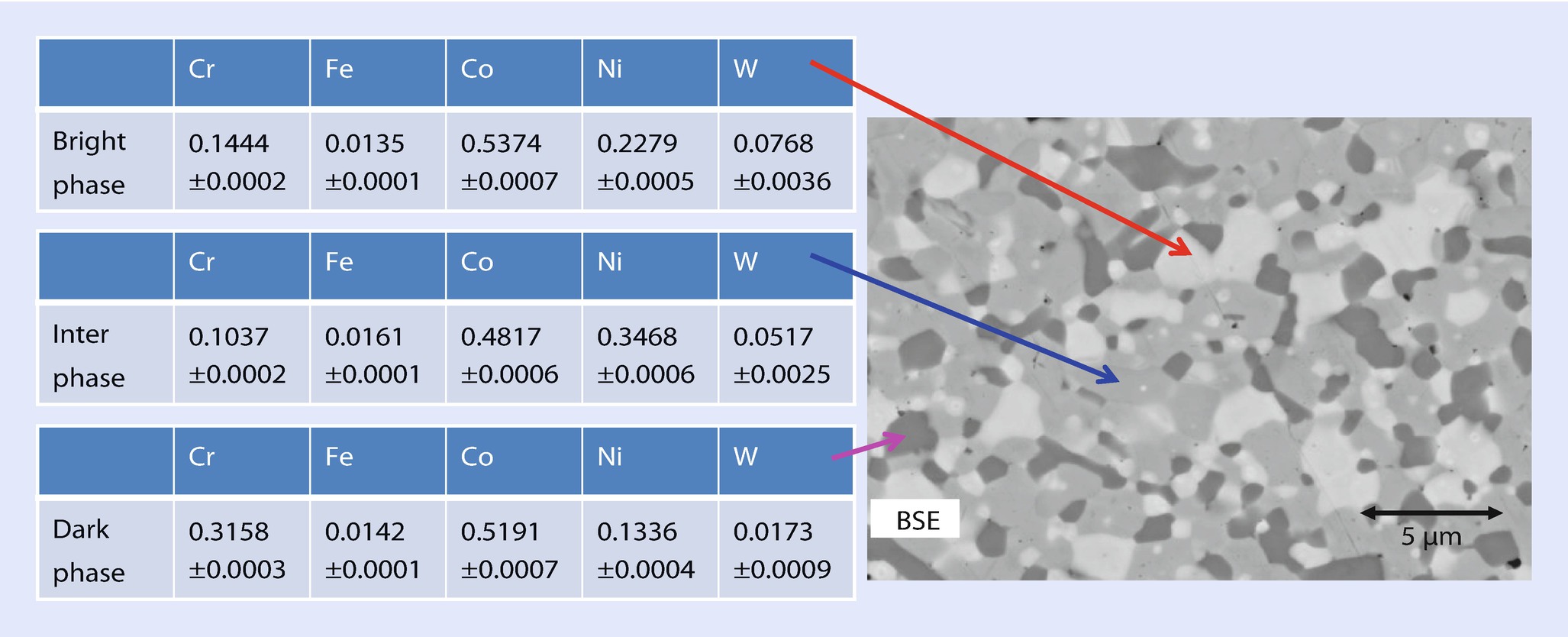

Elemental mapping of an area of fine-scale grains

SEM-BSE image and DTSA-II analyses of selected grains in the fine-scale region

The information provided by SEM-EDS enabled metallurgists to modify the hard-facing alloy composition and deposition conditions to eliminate the void formation during deposition, producing satisfactory service behavior.

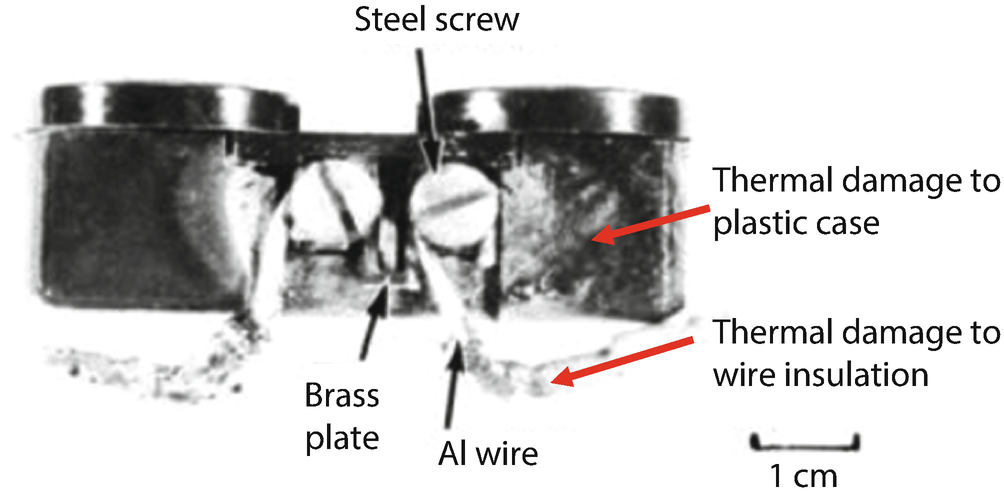

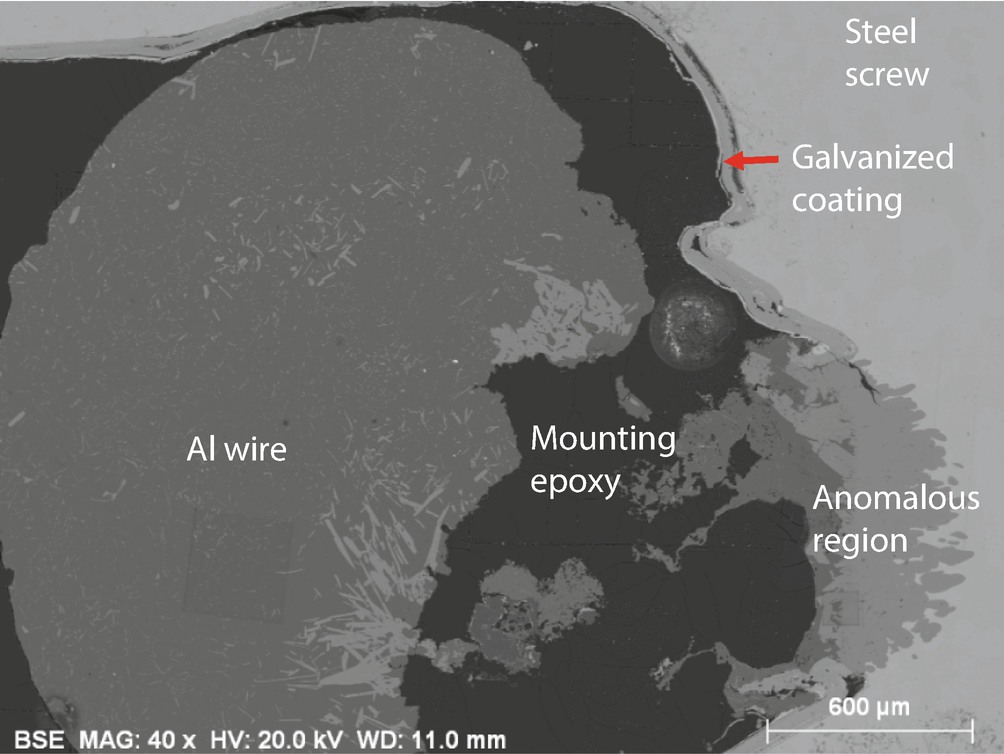

27.2 Case Study: Aluminum Wire Failures in Residential Wiring

Residential electrical outlet wired with aluminum. The laboratory test was interrupted after the thermal event initiated and was automatically detected, but significant thermal damage to the plastic casing and wire insulation still occurred

Metallographic mount (2.5-cm diameter) showing the cross section of the steel screw, aluminum wire, and brass plate

SEM-BSE image of an anomalous zone of contact between the Al wire and the Fe screw

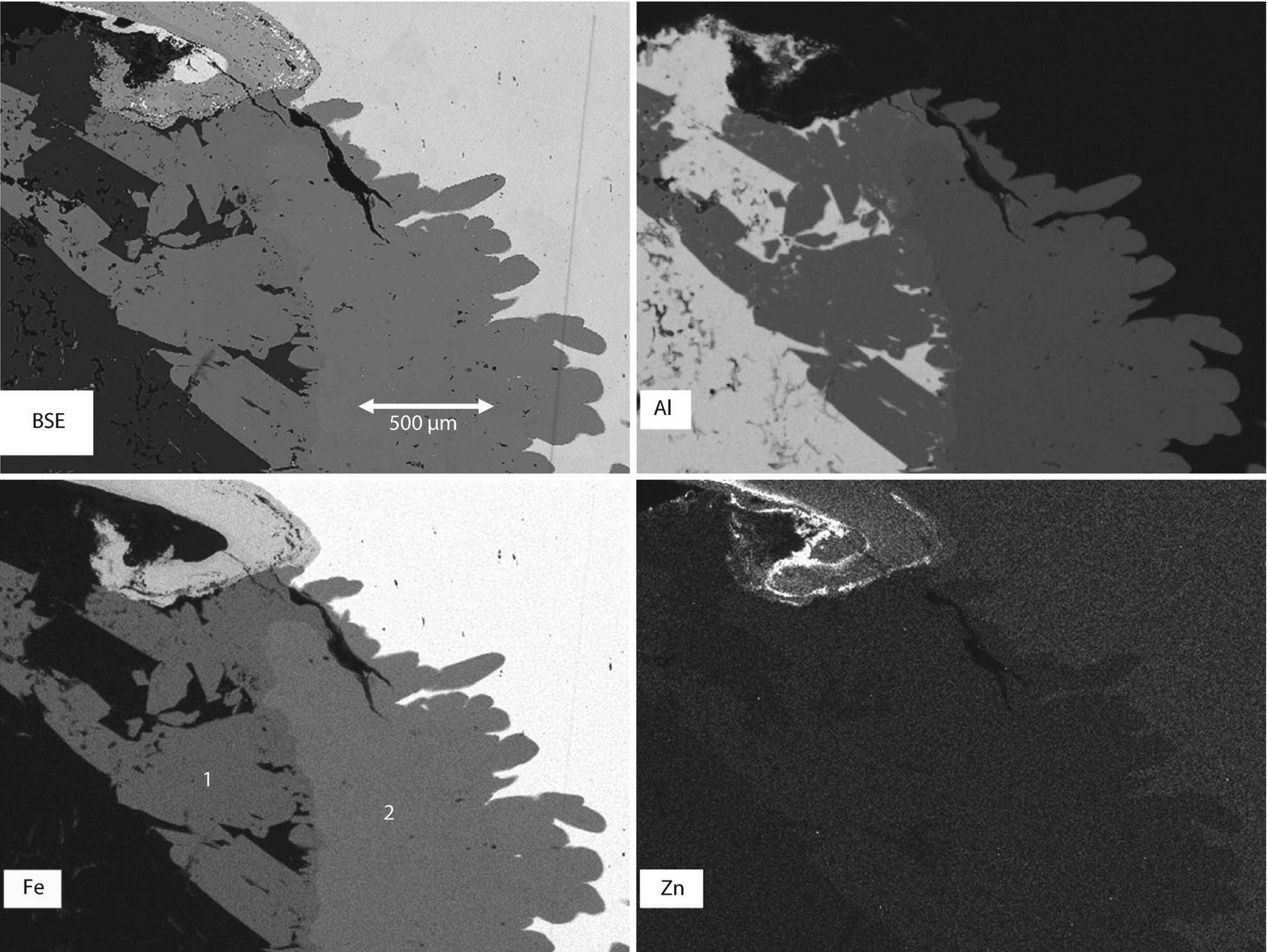

SEM-BSE image and elemental maps for Al, Fe, and Zn of the anomalous contact zone

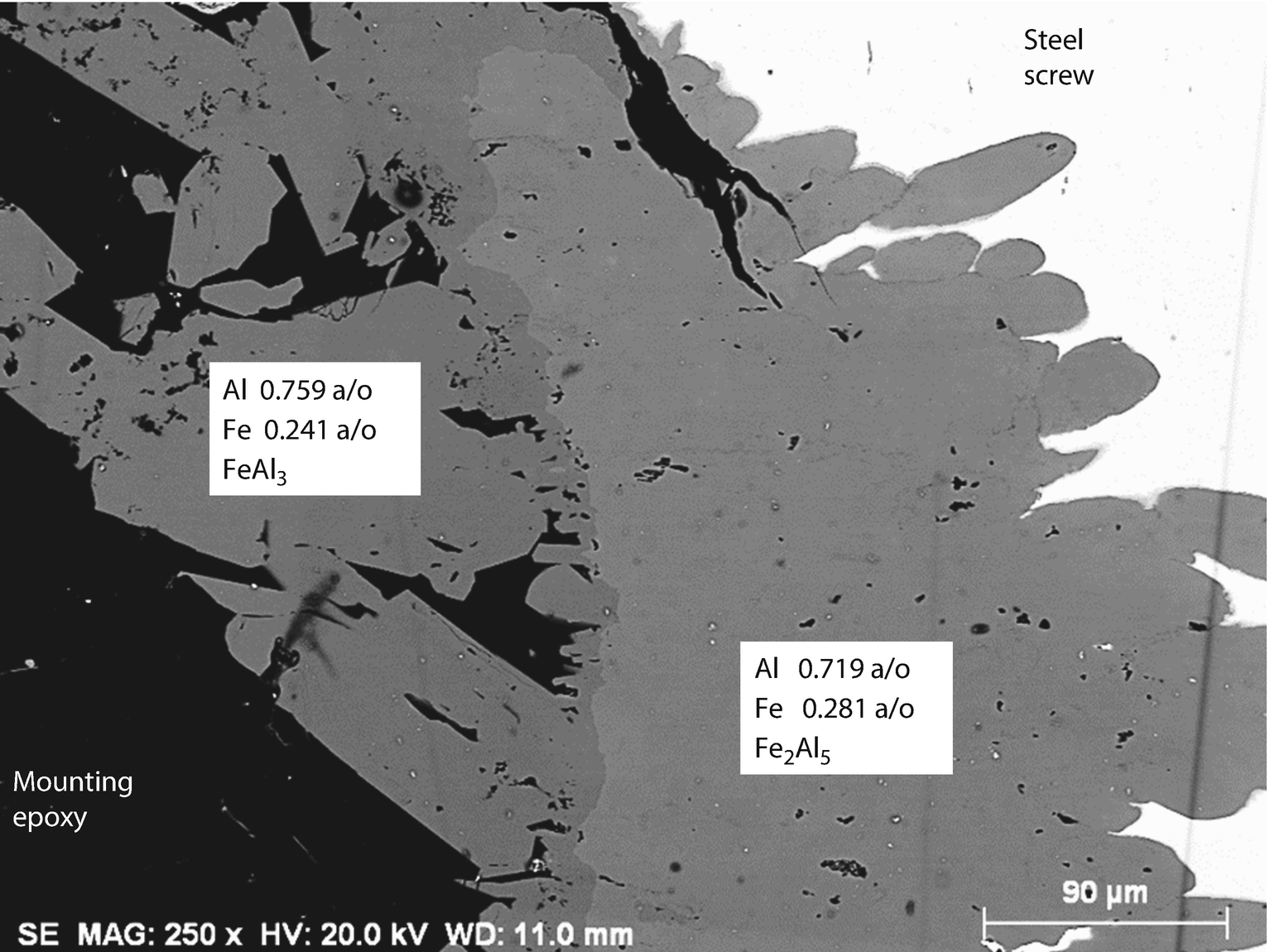

SEM-BSE image of the anomalous zone of contact with quantitative X-ray microanalysis results from fixed-beam analysis in the two distinct Al-Fe regions (note the contrast in the BSE image)

27.3 Case Study: Characterizing the Microstructure of a Manganese Nodule

“Manganese nodules” are rock concretions that form on the deep sea floor through the action of microorganisms that precipitate solid chemical forms from metals dissolved in the water, often in close association with hydrothermal vents.

Manganese nodule

SEM/BSE image of a polished cross section; note the cracks

SEM/EDS X-ray spectrum imaging elemental maps for Mn, O, and Ni and color overlay (Mn = red; O = green; Ni = blue). Note cracks are observed in the O map but are much less visible in Mn and Ni

SEM/EDS X-ray spectrum imaging elemental maps for Mn, Fe, and Ni and color overlay (Mn = red; Fe = green; Ni = blue)

SEM/EDS X-ray spectrum imaging elemental maps for Mn, Si, and Al and color overlay (Mn = red; Si = green; Al = blue)

Fixed-beam analysis at the center of ◘ Fig. 27.12; NIST DTSA II analysis with pure element and microanalysis glass standards

O | Na | Mg | Al | Si | K | Ca | Ti | Mn | Fe | Ni | Cu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

0.2742 ± 0.0003 | 0.0420 ± 0.0005 | 0.0196 ± 0.0002 | 0.0210 ± 0.0001 | 0.0458 ± 0.0002 | 0.0100 ± 0.0000 | 0.0267 ± 0.0001 | 0.0031 ± 0.0000 | 0.4412 ± 0.0003 | 0.0834 ± 0.0002 | 0.0196 ± 0.0001 | 0.0134 ± 0.0002 |

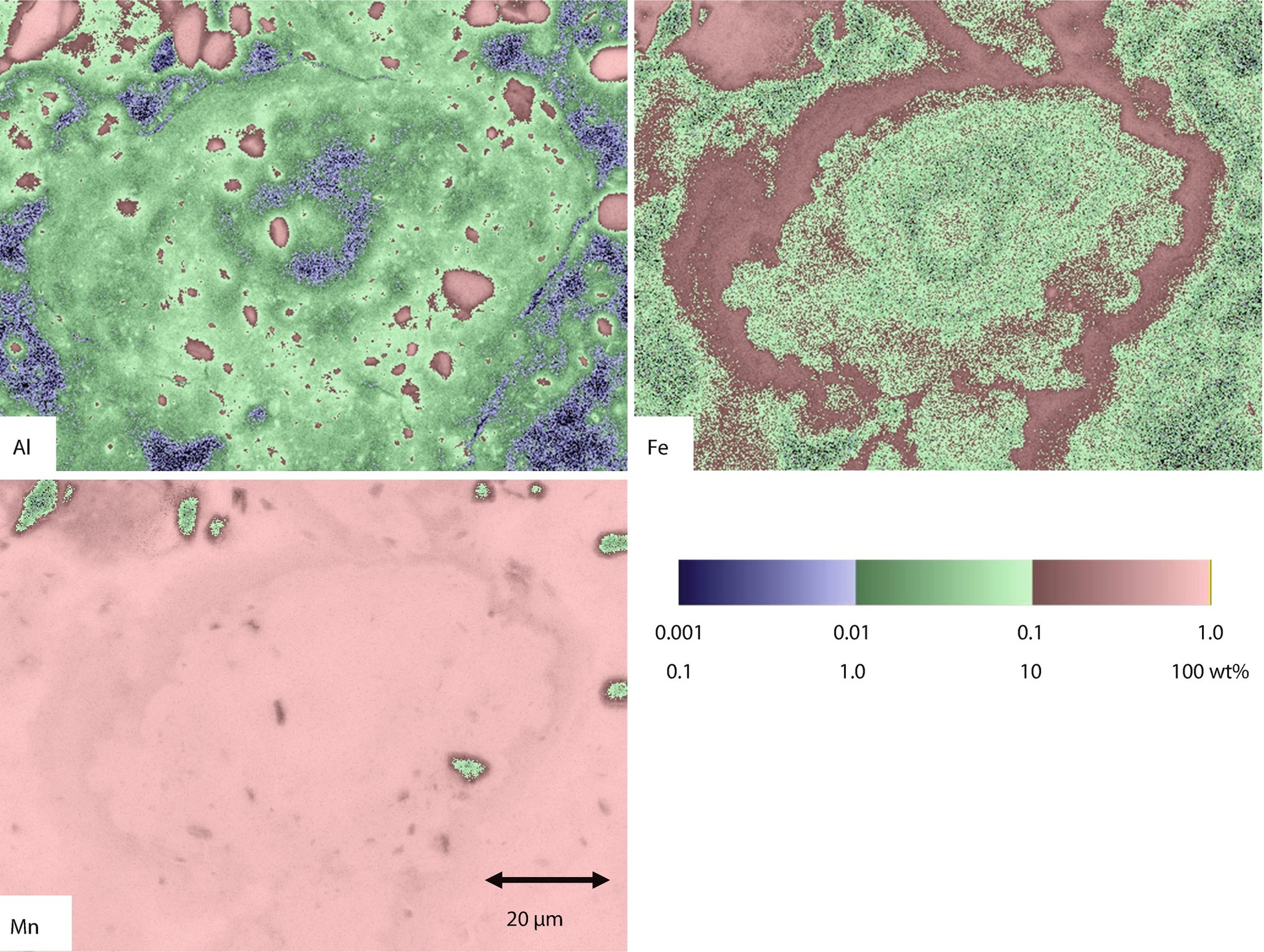

SEM/EDS X-ray spectrum imaging maps after quantitative analysis with DTSA-II presented with logarithmic three-band encoding for Al, Fe, and Mn. Note Fe-enrichment band

Note that some features in the elemental maps are a result of artifacts. Thus, the cracks noted in the SEM/BSE of ◘ Fig. 27.11 are also seen in the O elemental map, but not in the Mn or Ni maps. The origin of this artifact is the difference in the photon energies of these elements. The O K-shell X-ray at an energy of 0.523 keV suffers strong absorption when the electron beam is located in the crack, so that the intensity is greatly reduced, producing an accurate representation of the crack. The MnK-L2,3 (5.898 keV) and NiK-L2,3 (7.477 keV) photons have higher energy and suffer much less absorption, so that most of those photons generated when the beam is in the crack still escape despite having to pass through more material to reach the EDS, greatly reducing the contrast of the cracks relative to the surrounding matrix.

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.