28.1 Origin

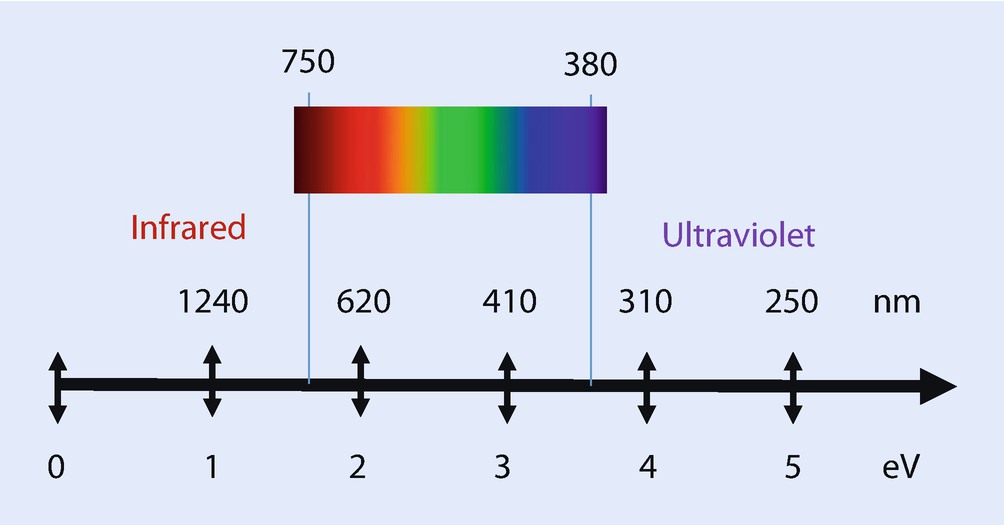

Range of photon energies and wavelengths for cathodoluminescence

a Origin of intrinsic CL: the material’s electron energy states fill the valence band which is separated by a band-gap of several eV from an empty conduction band. Inelastic scattering of the beam electron promotes a valence band electron to the conduction band, leaving a positively charged hole in the valence band. b Origin of intrinsic CL: The free electron and hole are mutually attracted and recombine, with the energy released as an electromagnetic photon with a minimum energy equal to the band-gap energy

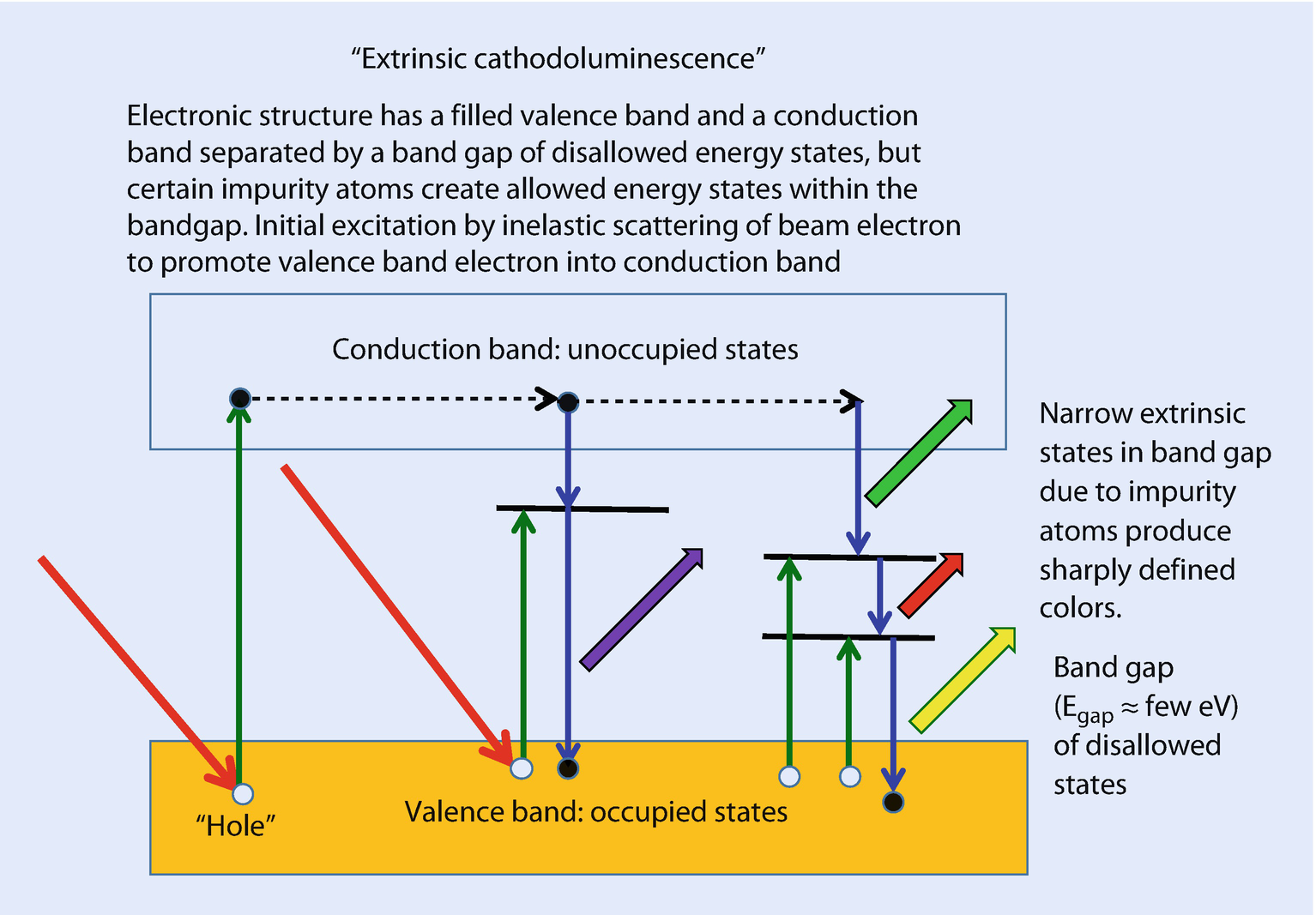

Origin of extrinsic CL: the presence of impurity atoms in the host lattice creates narrow energy levels within the band-gap. Inelastic scattering of the beam electron can promote valence band electrons to the conduction band as well as to the impurity levels in the band-gap. Electron transitions can occur between the various energy levels, creating both broadband CL emission and sharply defined CL emission

28.2 Measuring Cathodoluminescence

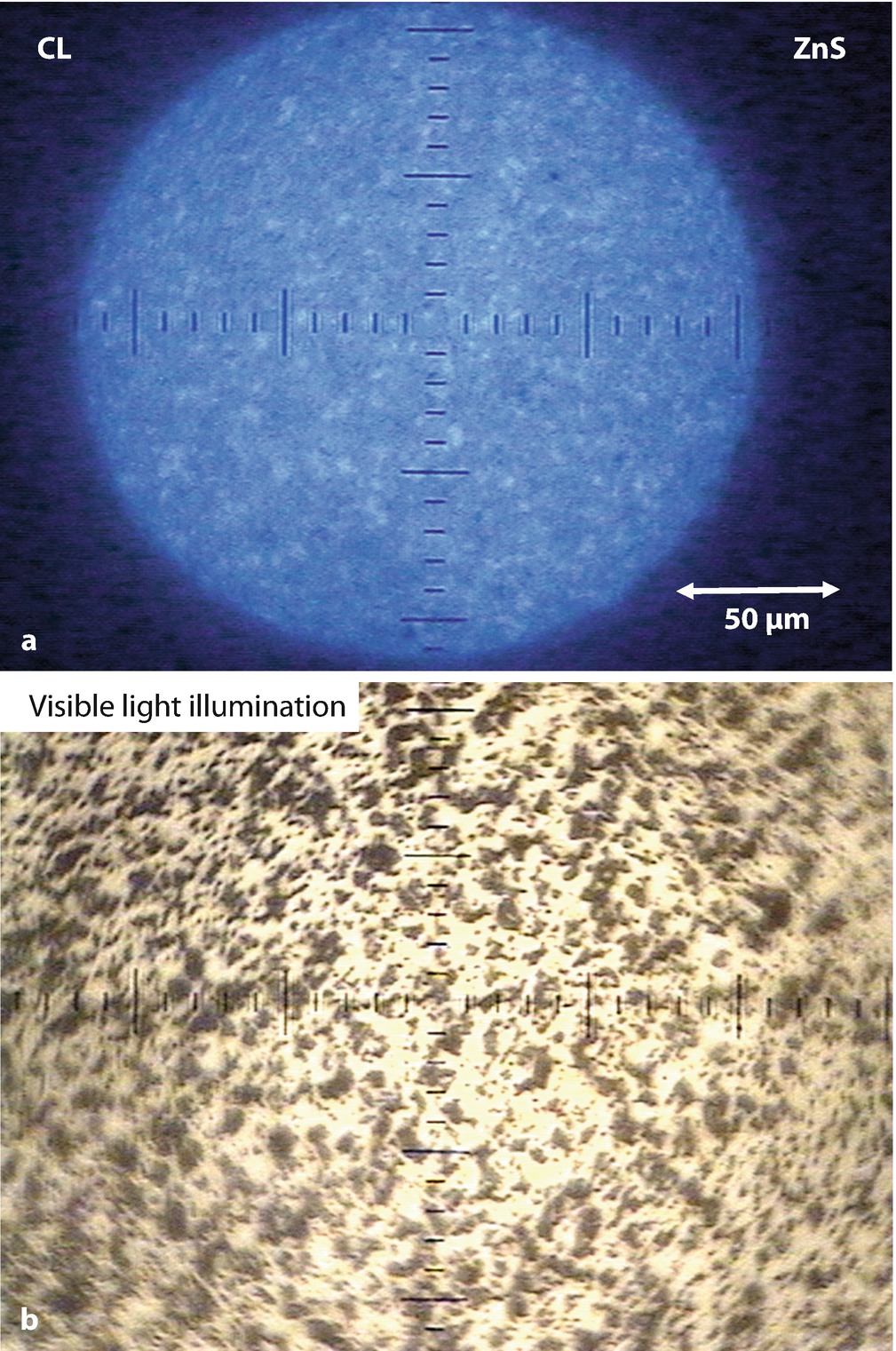

a CL emission from ZnS observed with a defocused 220-μm-diameter beam with 500 nA of beam current at E 0 = 20 keV. b Corresponding white light illumination image with the electron beam blanked into a Faraday cup

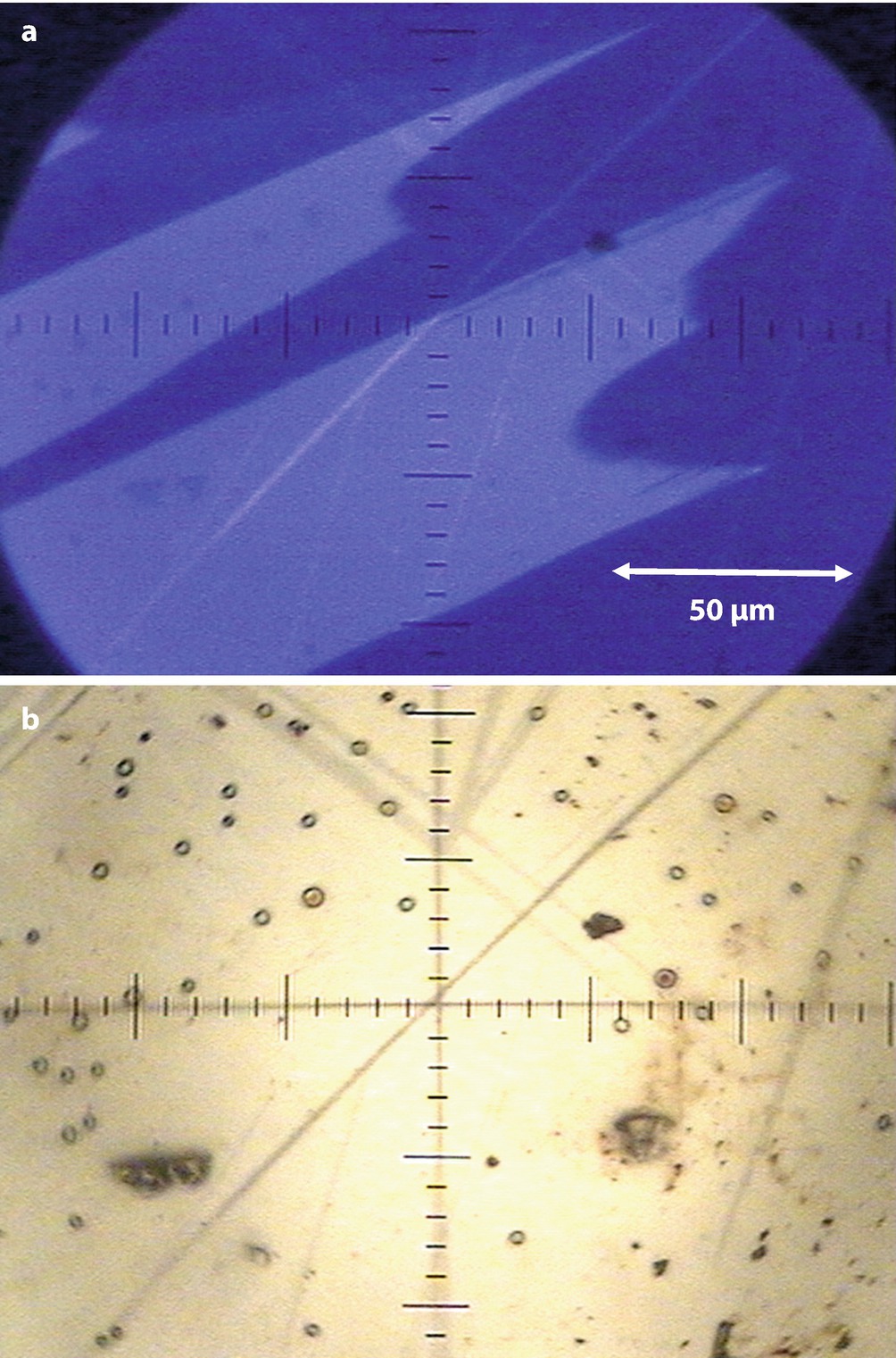

a CL emission from the mineral Benitoite (BaTiSi3O9) observed with a defocused 220-μm-diameter beam with 500 nA of beam current at E 0 = 20 keV. b Corresponding white light illumination image with the electron beam blanked into a Faraday cup

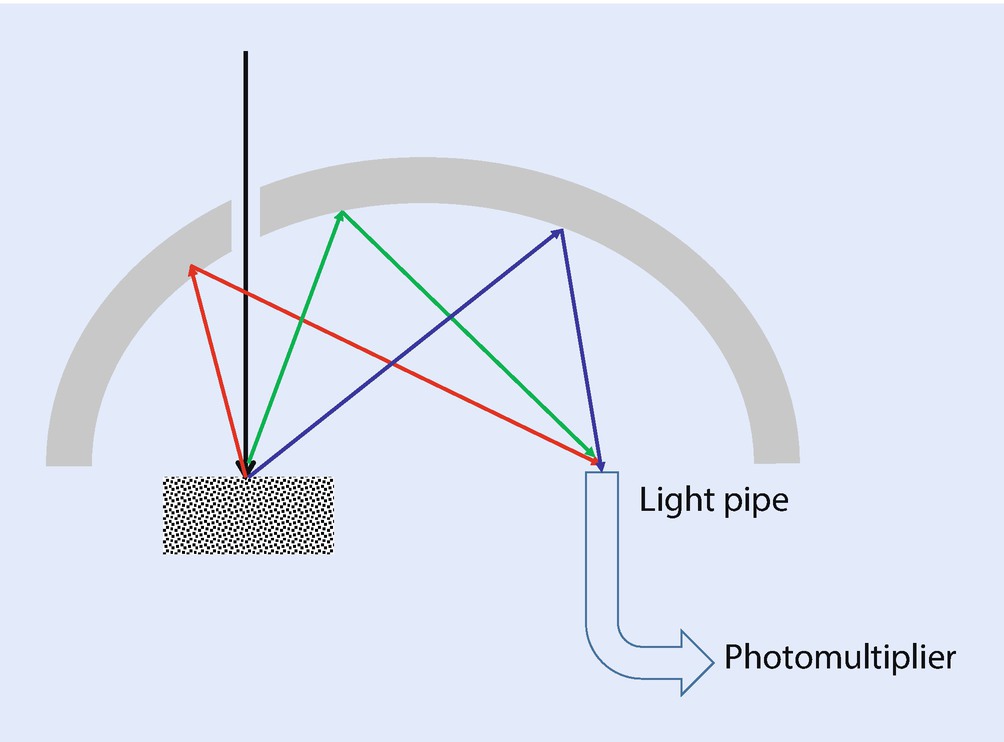

28.2.1 Collection of CL

Schematic diagram of a high efficiency CL collection optic based upon an ellipsoidal mirror

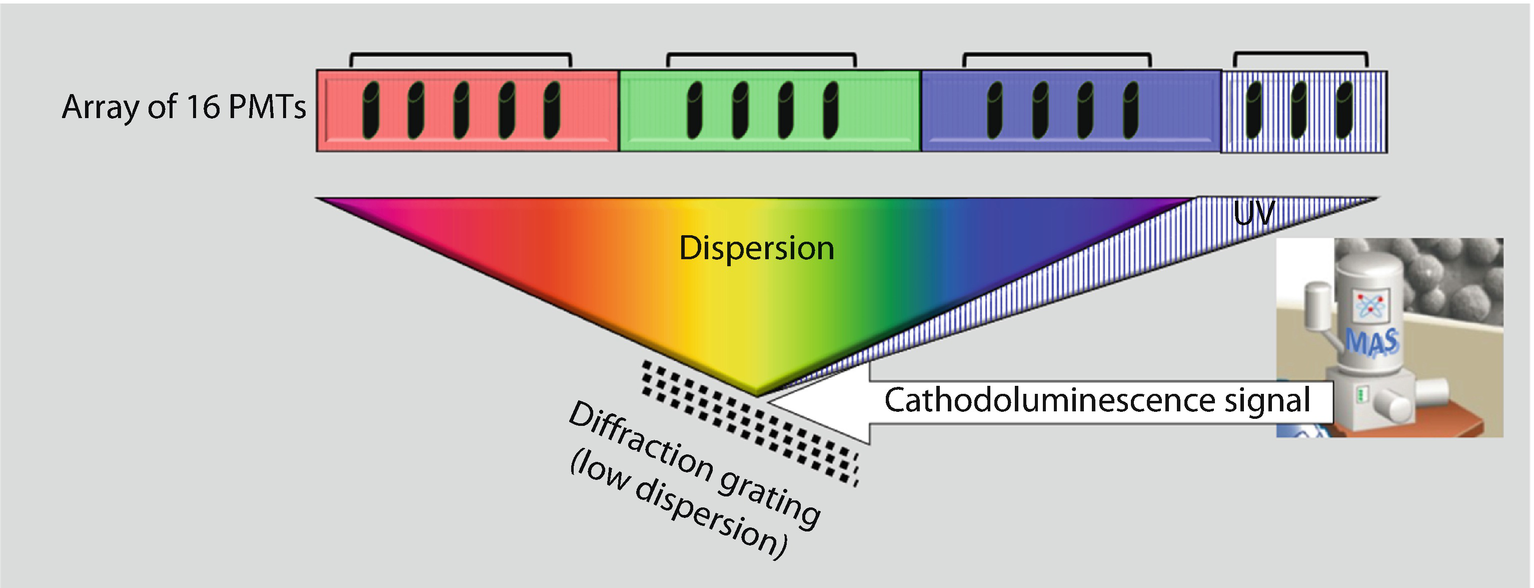

28.2.2 Detection of CL

Schematic diagram of a dispersive CL system with an array of photomultpliers to sample a broad range of CL photon energies in parallel (courtesy of Gatan, Inc.)

Another detection scheme makes use of a single wide energy response photomultiplier to detect CL photons across the energy range. To separate the different color components of the CL emission, repeated scans of the area of interest are made with color filters (red, green, and blue) in the optical path to the PM, and the R-, G-, and B-images are combined.

Systems in which the photons are passed into a scanning optical spectrometer make possible detailed study of the CL emission in a single channel mode of operation.

28.3 Applications of CL

28.3.1 Geology

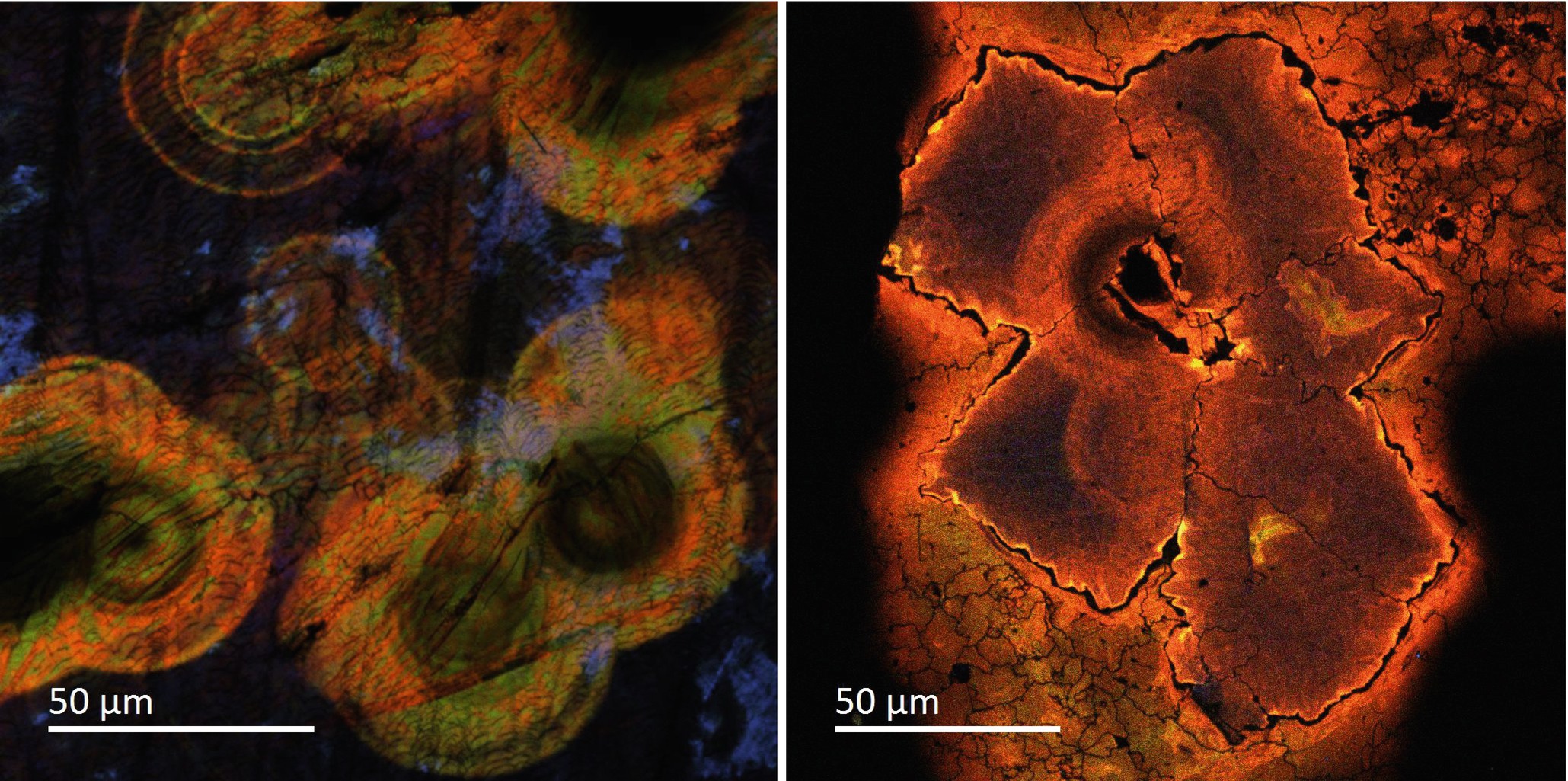

28.3.1.1 Carbonado Diamond

Carbonado is a rare variety of black diamond found in porous aggregates of fine polycrystals.

CL imaging (RGB) of a carbonado, a rare variety of diamond. The polycrystalline material interacted with uranium during the Precambrian and MeV radiation damage is evident as metamict halos leaving the defects in the diamond structure (Magee et al. 2016) (Images courtesy of E. Vicenzi (Smithsonian Institution))

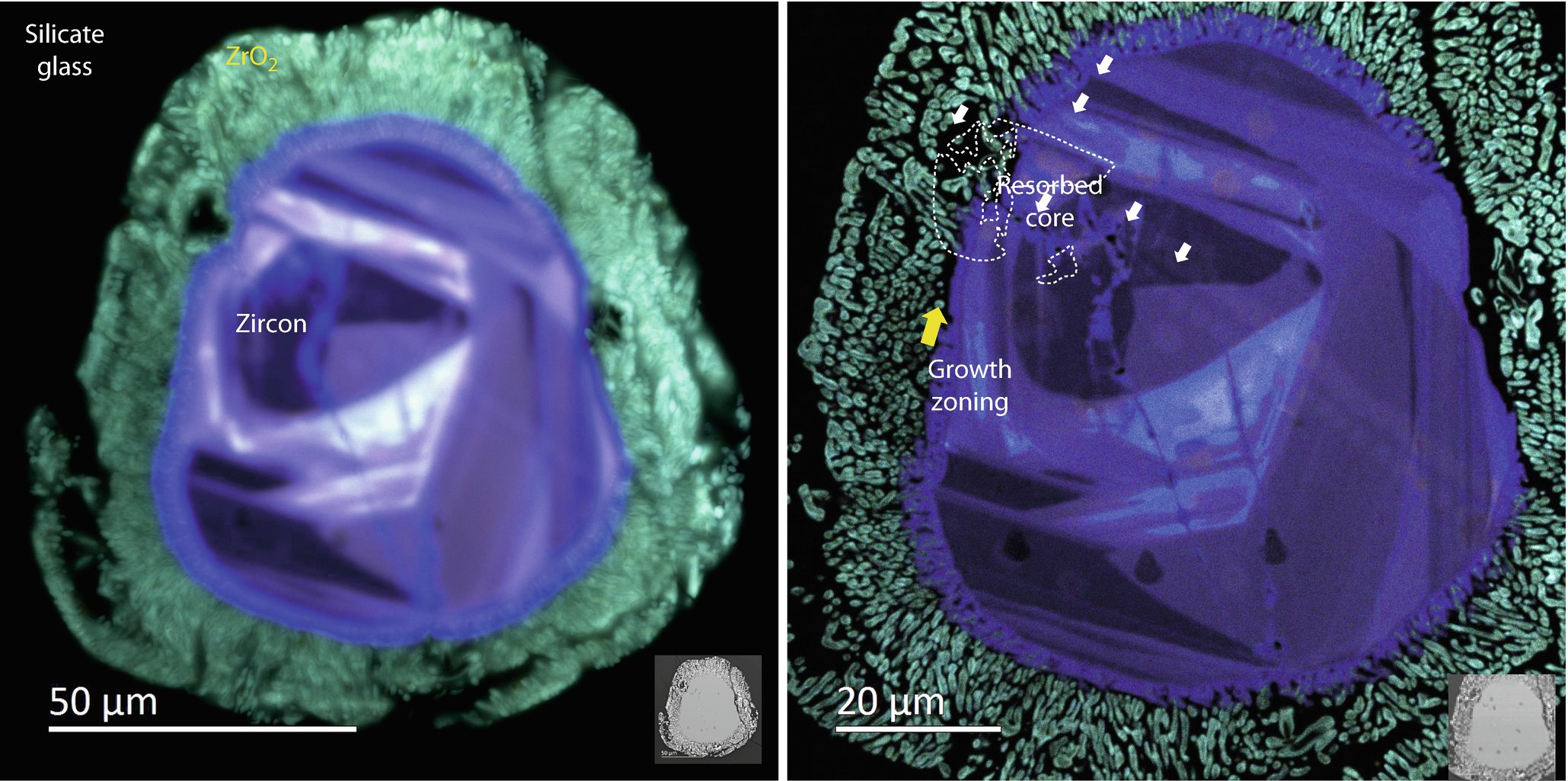

28.3.1.2 Ancient Impact Zircons

CL imaging (RGB) of an impact zircon collected using E 0 = 20 keV (left) and 5 keV (right). The details of zircon disproportionation to ZrO2 and silicate glass, as well as the zircon interior, are more evident using a low energy beam (Zanetti et al. 2015) (Images courtesy of E. Vicenzi (Smithsonian Institution))

28.3.2 Materials Science

28.3.2.1 Semiconductors

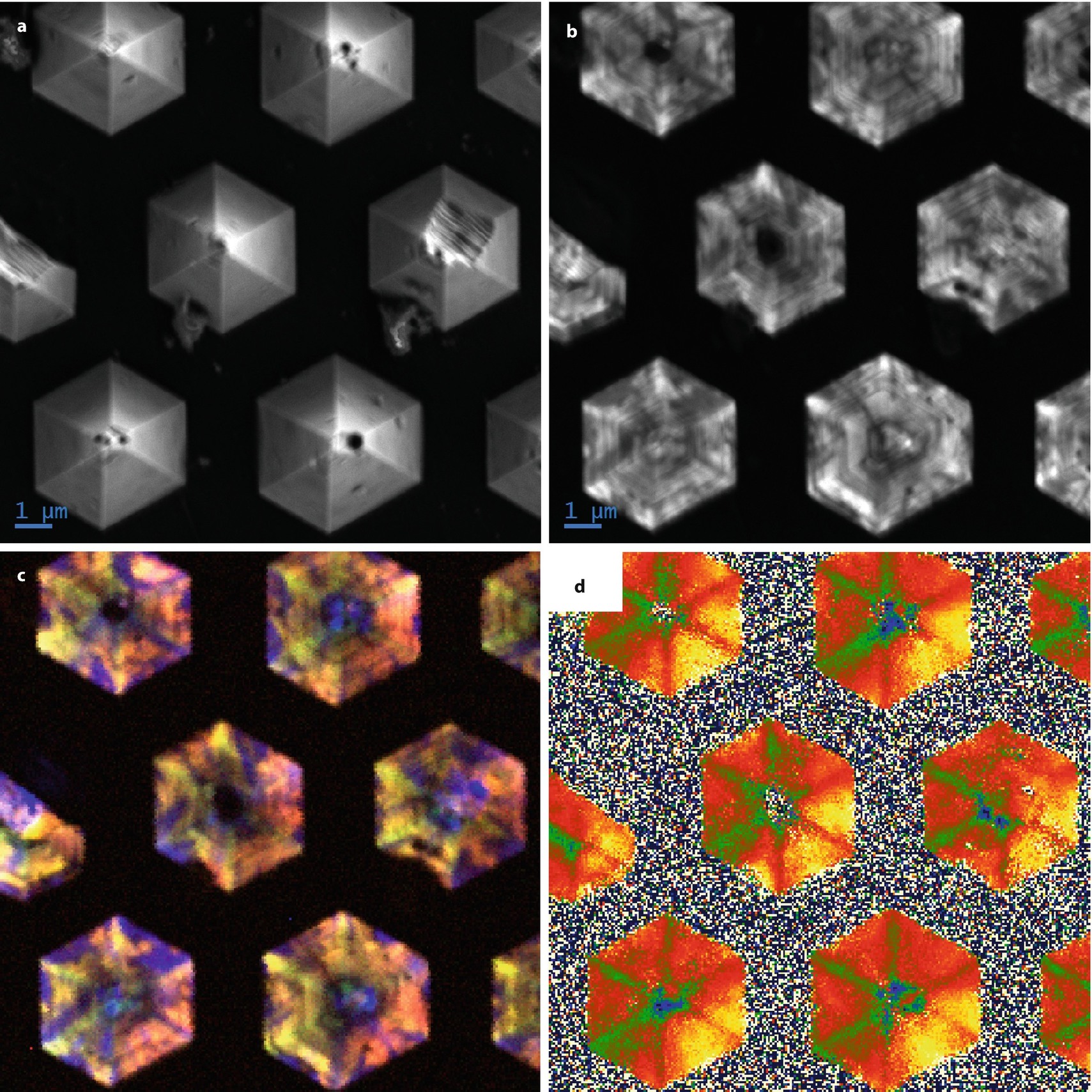

CL study of GaN structures grown on Si: a SEM SE image (E 0 = 2 keV); b panchromatic CL image; c CL spectrum image data analyzed to derive the central wavelength value; d RGB composite (Example courtesy of D. Stowe, Gatan, Inc.)

28.3.2.2 Lead-Acid Battery Plate Reactions

It is possible to detect relatively strong CL signals with modified BSE detectors, as most of these solid state detectors are very sensitive to light. The challenge is to exclude BSE from the detected signal. The easiest way to do this is to coat a glass coverslip with a conductive transparent material like indium tin oxide (ITO). The glass cover slip prevents the electrons from interacting with the solid state detector and the conductive transparent coating prevents charging while allowing the CL signal to reach the detector.

It is interesting to note that some of the low vacuum or variable pressure SEMs that are commercially available use the CL light generated by the interaction of the secondary electrons with the gas in the chamber to produce a signal during variable pressure operation. One can use the same detector system, which consists of a glass light guide located near the sample that is coupled to a photomultiplier, for direct detection of CL emission. This type of detector is sensitive to low levels of light and thus when used in high vacuum mode can be a very simple but effective CL detector.

a SEM SE image of deposits on lead-acid battery. b CL image of the same area; c DTSA-II simulation of the EDS spectra of PbS and PbSO4 from an ideal flat surface at E 0 = 15 keV (courtesy of Sandia National Laboratory)

28.3.3 Organic Compounds

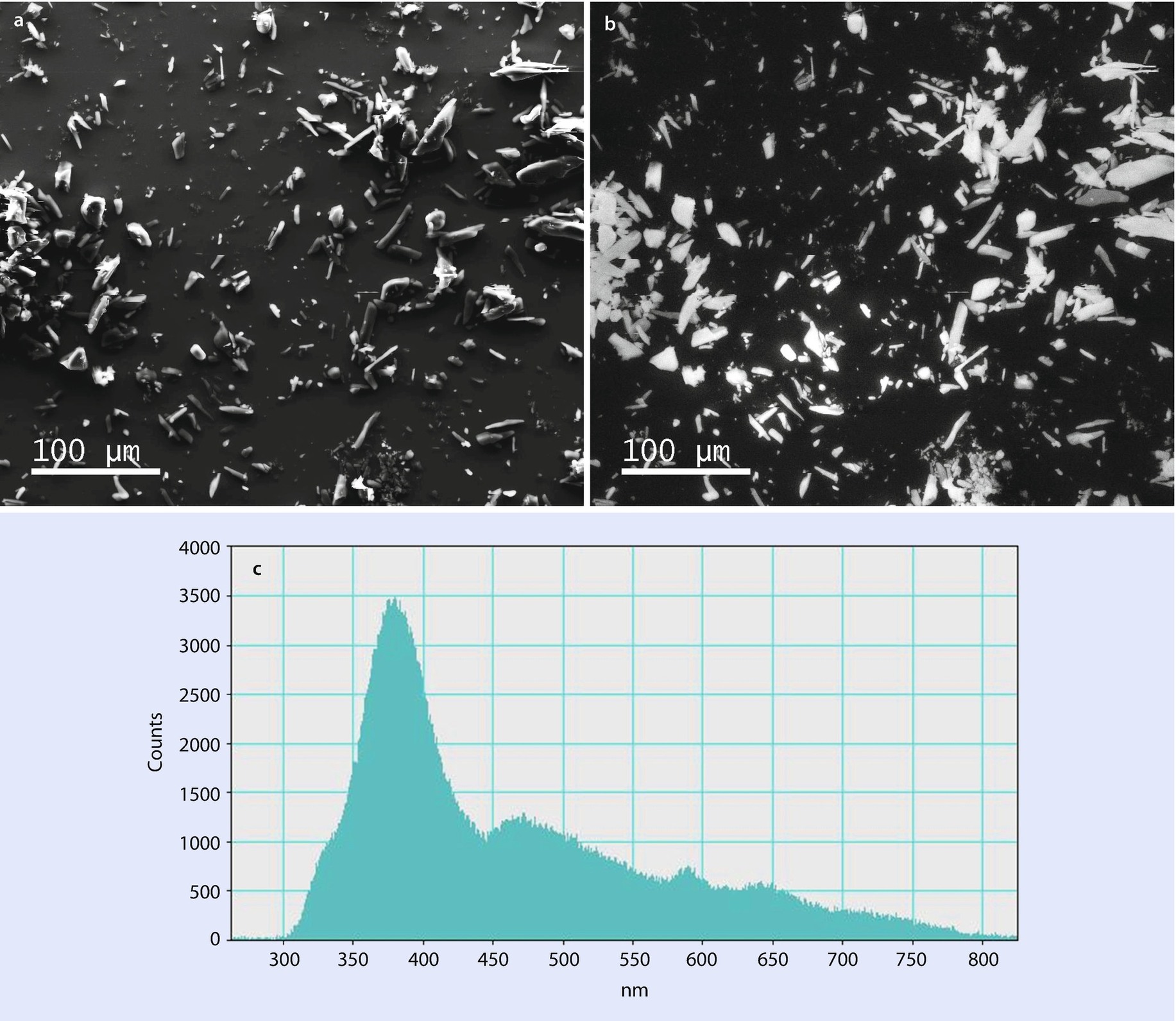

Acetaminophen, E 0 = 20 keV: a SEM SE image; b panchromatic CL image; c CL spectrum (Example courtesy of S. Wight, NIST)

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.