6.1 Image Construction by Scanning Action

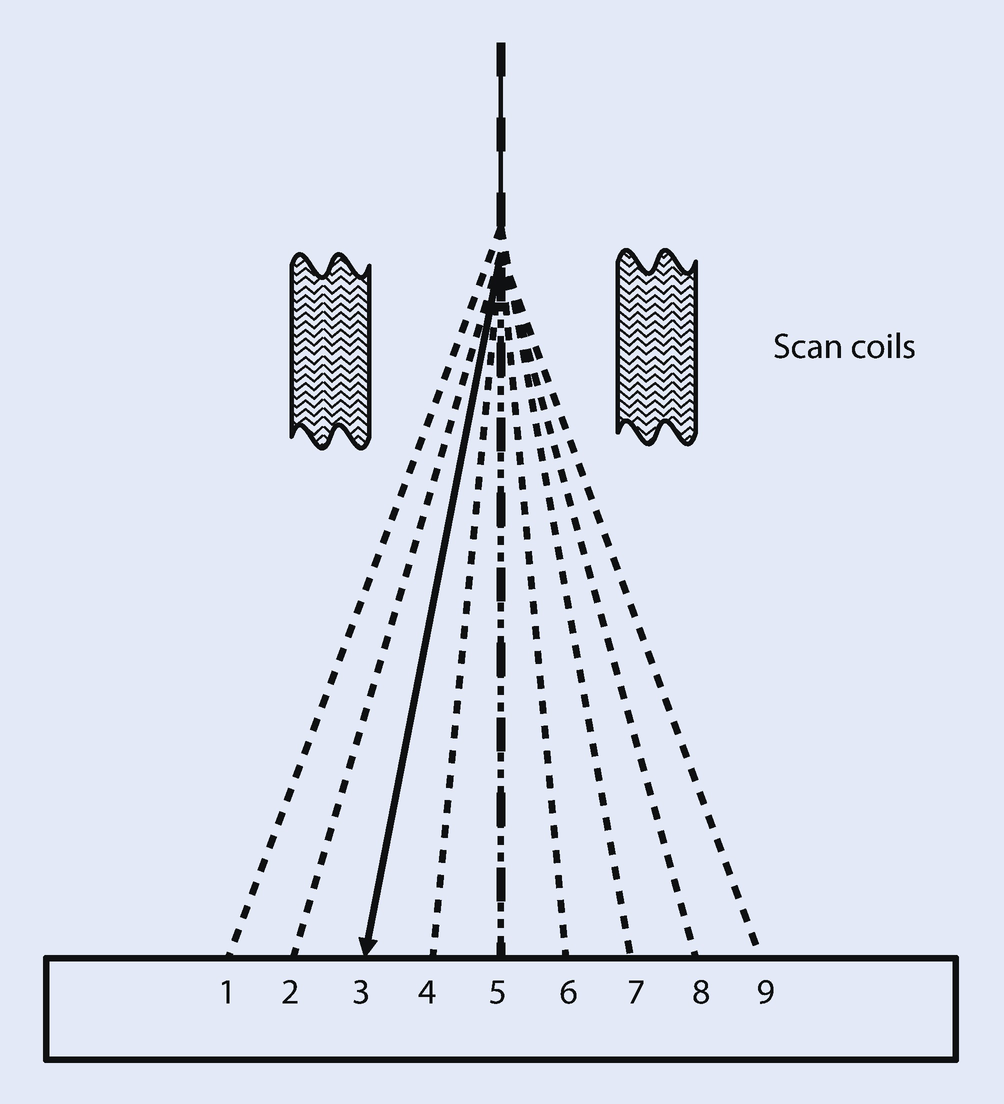

Scanning action to produce a sequence of discrete beam locations on the specimen

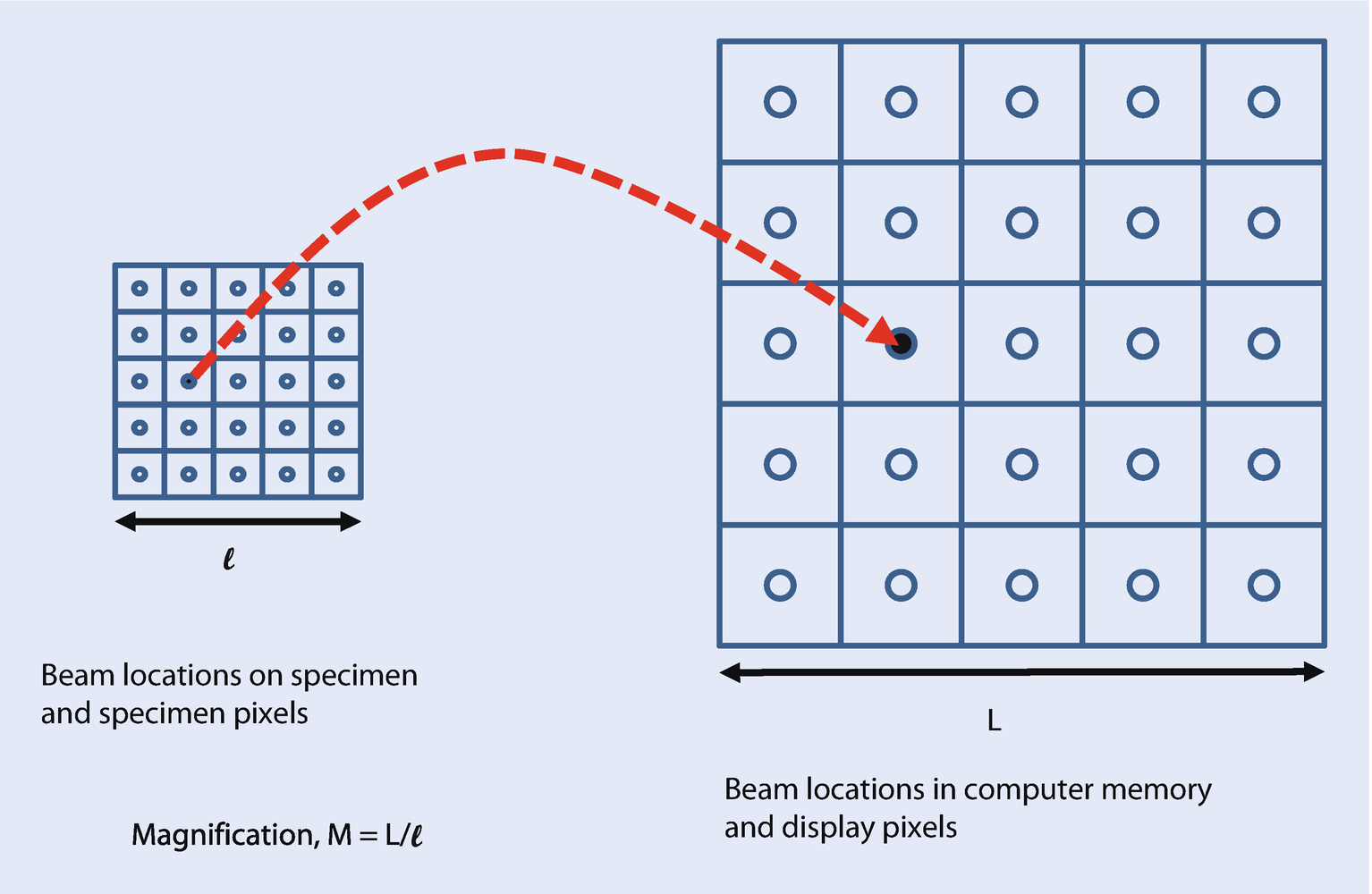

Scanning action in two dimensions to produce an x-y raster, and the corresponding storage and display of image information by scan location

6.2 Magnification

6.2.1 Magnification, Image Dimensions, and Scale Bars

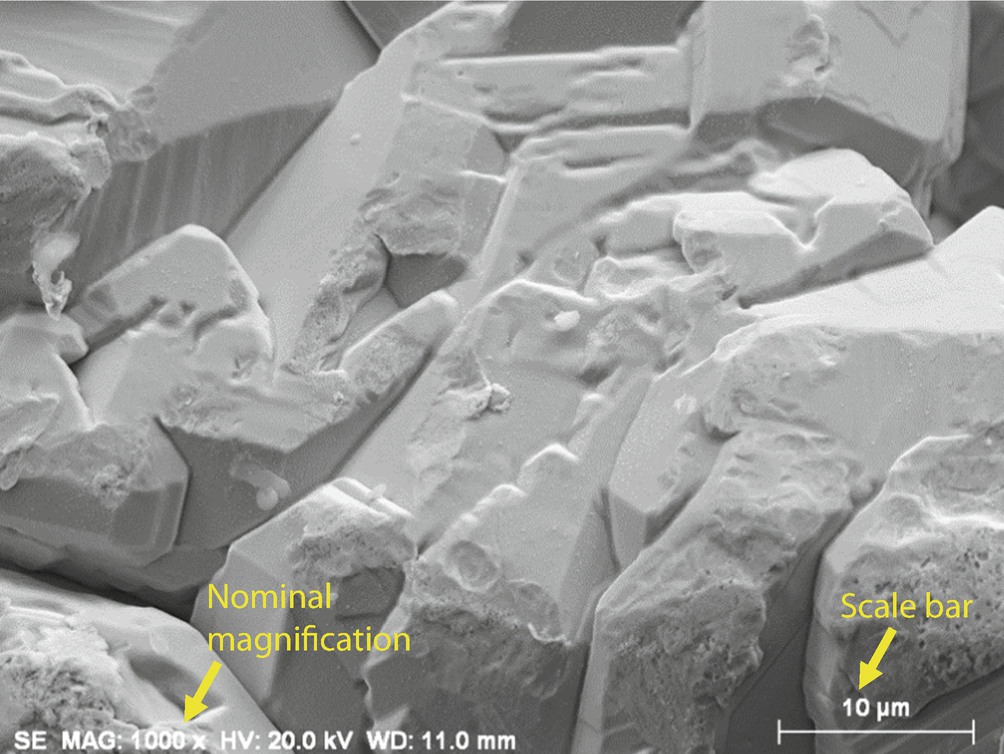

SEM-SE image of silver crystals showing a typical information bar specifying the electron detector, the nominal magnification, the accelerating voltage, and a scale bar

6.3 Making Dimensional Measurements With the SEM: How Big Is That Feature?

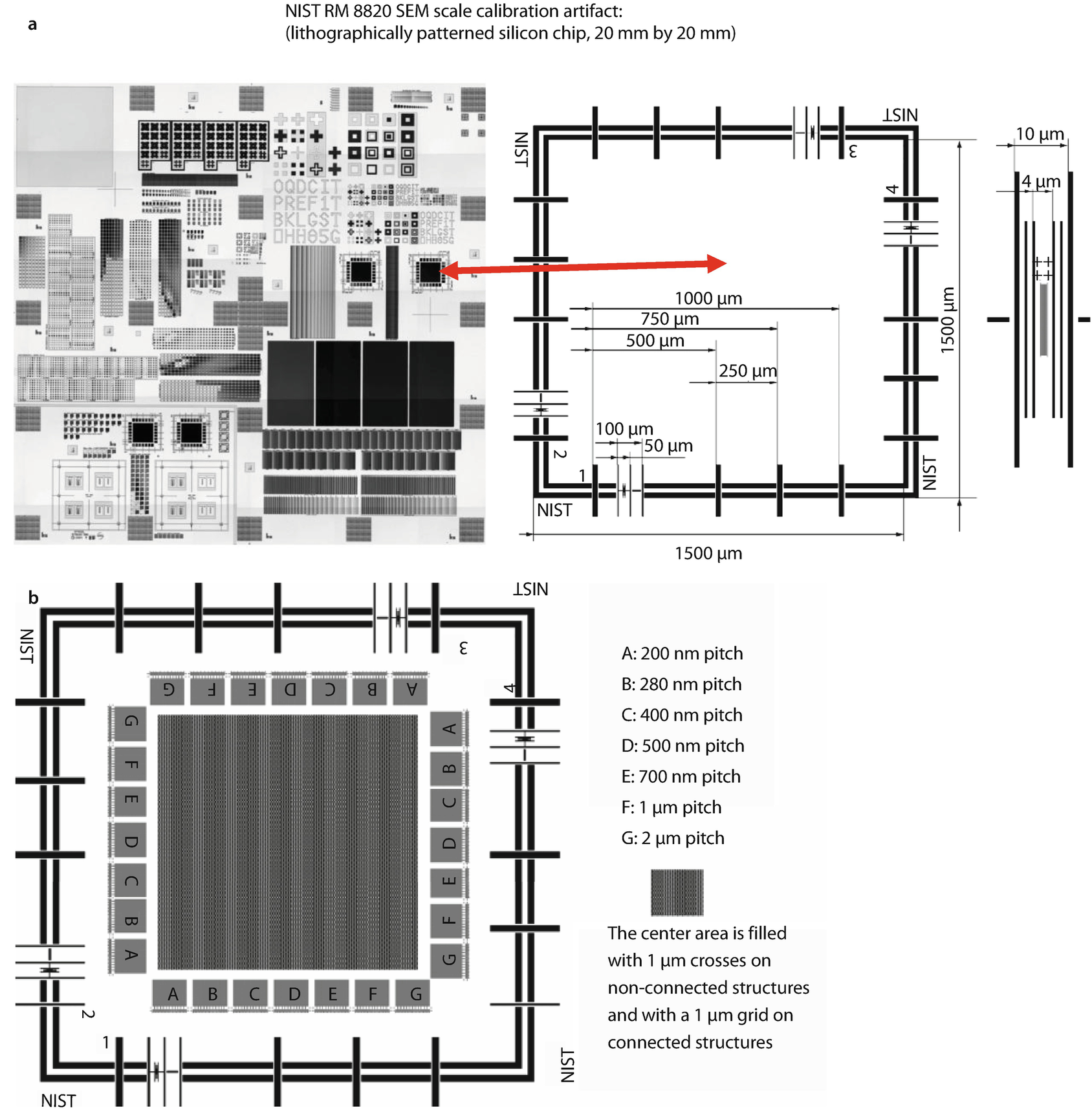

6.3.1 Calibrating the Image

a Careful calibration of the x- and y-scans produces square pixels, and a faithful reproduction of shapes lying in the scan plane perpendicular to the optic axis. b Distortion in the display of an object caused by non-square pixels in the image scan

Note that for all measurements the calibration artifact must be placed normal to the optic axis of the SEM to eliminate image foreshortening effects (see further discussion below).

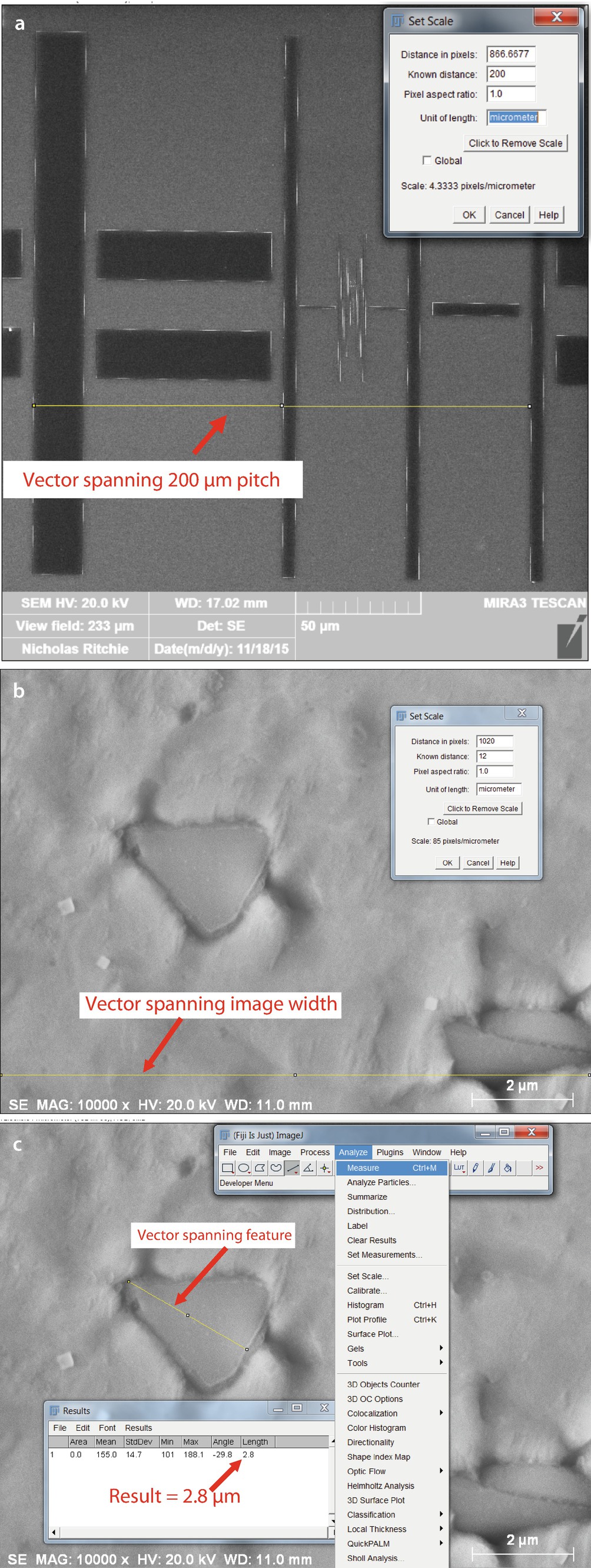

6.3.1.1 Using a Calibrated Structure in ImageJ-Fiji

a ImageJ (Fiji) “Set Scale” calibration function applied to an image of NIST RM 8820. b ImageJ (Fiji) “Set Scale” calibration function applied to an image of an unknown (alloy IN100). c After “Set Scale” image calibration, subsequent use of ImageJ (Fiji) “Measure” function to determine the size of a feature of interest

Alternatively, if the SEM magnification calibration has already been performed with an appropriate calibration artifact, then subsequent images of unknowns will be recorded with accurate dimensional information in the form of a scale bar and/or specified scan field dimensions. This information can be used with the “Set Scale” function in ImageJ-Fiji as shown for a specified field width in ◘ Fig. 6.6b where a vector (yellow) has been chosen that spans the full image width. The “Set Scale” tool will record this length and the user then specifies the “Known Distance” and the “Unit of Length.” To minimize the effect of the uncertainty associated with selecting the endpoints when defining the scale for this image, the larger of the two dimensions reported in the vendor software was chosen, in this case the full horizontal field width of 12 μm rather than the much shorter embedded length scale of 2 μm.

6.3.1.2 Making Routine Linear Measurements With ImageJ-Fiji (Flat Sample Placed Normal to Optic Axis)

For the case of a flat sample placed normal to the optic axis of the SEM, linear measurements of structures can be made following a simple, straightforward procedure after the image calibration procedure has been performed. Typical image-processing software tools directly available in the SEM operational software or in external software packages such as ImageJ-Fiji enable the microscopist to make simple linear measurements of objects. With the calibration established, the “Line” tool is used to define the particular linear measurement to be made, as shown in ◘ Fig. 6.6c, and then the “Measure” tool is selected, producing the “Results” table that is shown. Repeated measurements will be accumulated in this table.

6.4 Image Defects

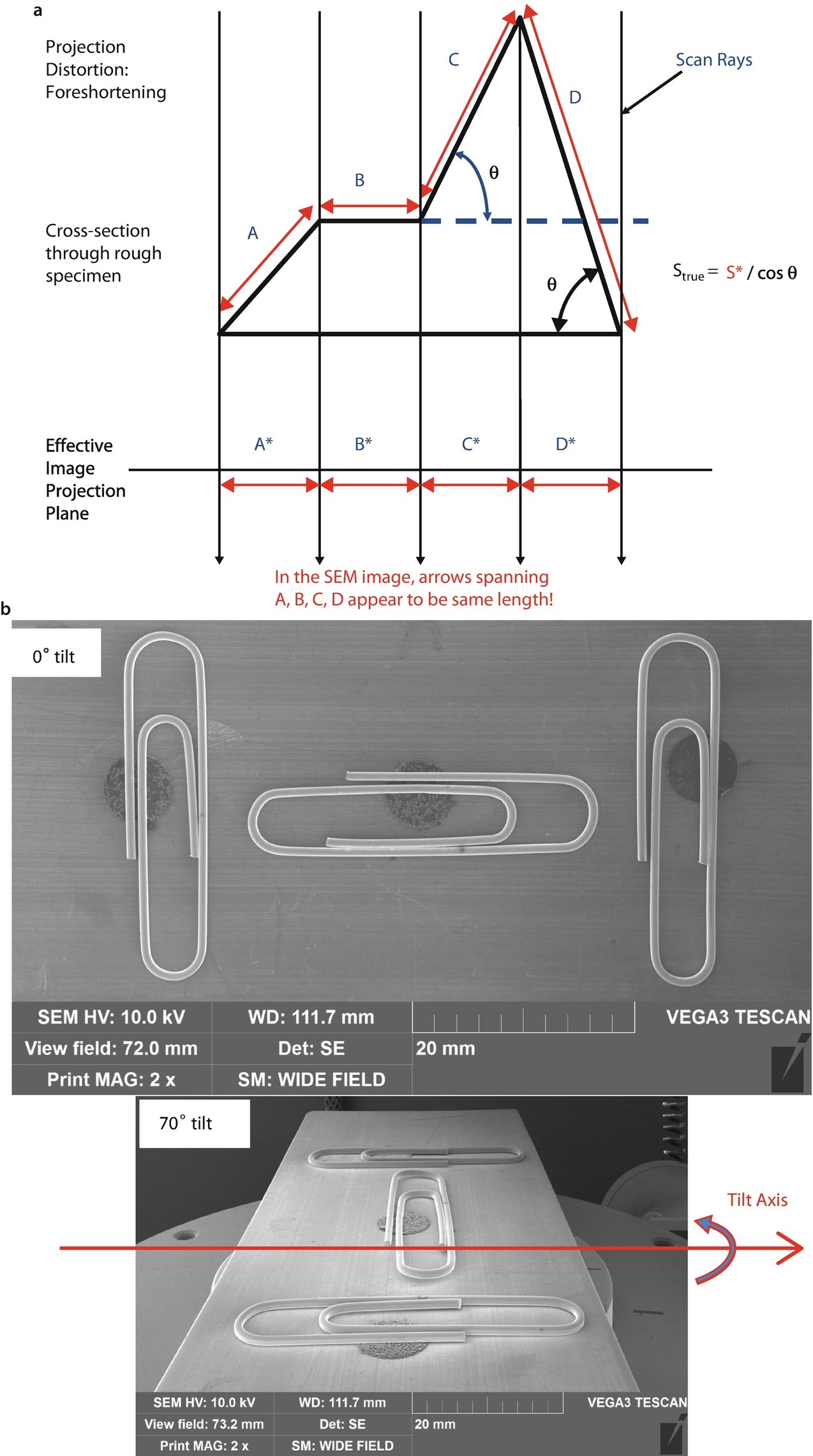

6.4.1 Projection Distortion (Foreshortening)

a Schematic illustration of projection distortion of tilted surfaces. b Illustration of foreshortening of familiar objects, paper clips (upper) Large area image at 0 tilt; (lower) large area image at 70° tilt around a horizontal tilt axis. Note that parallel to the tilt axis, the paper clips have the same size, but perpendicular to the tilt axis severe foreshortening has occurred. The magnification also decreases significantly down the tilted surface, so the third paper clip appears smaller than the first (Images courtesy J. Mershon, TESCAN)

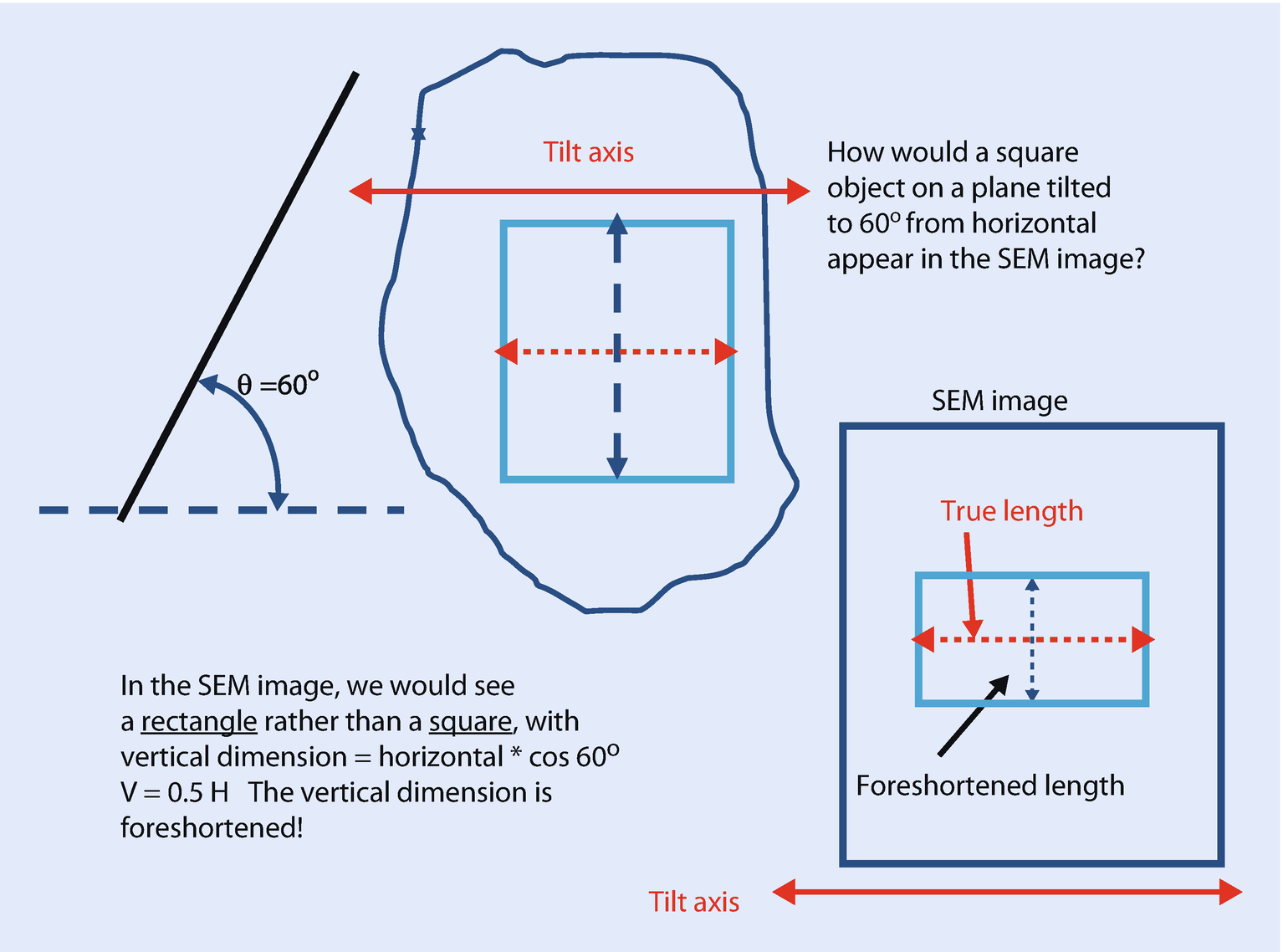

Effect of foreshortening of objects in a titled plane to distort square grid openings into rectangles

a SEM/E–T (positive) image of a copper grid with a polystyrene latex sphere; tilt = 0° (grid normal to electron beam). b Grid tilted to 45°; note the effect of foreshortening distorts the square grid openings into rectangles. c Grid tilted to 45°; “tilt correction” applied, but note that while the square grid openings are restored to the proper shape, the sphere is highly distorted

6.4.2 Image Defocusing (Blurring)

a The beam sampling footprint relative to the pixel spacing for a low magnification image with a low energy finely focused beam and a high atomic number target. b As the magnification is increased with fixed beam energy and target material, the beam sampling footprint (diameter and BSE-SE convolved) eventually fills the pixel and progressively leaks into adjacent pixels

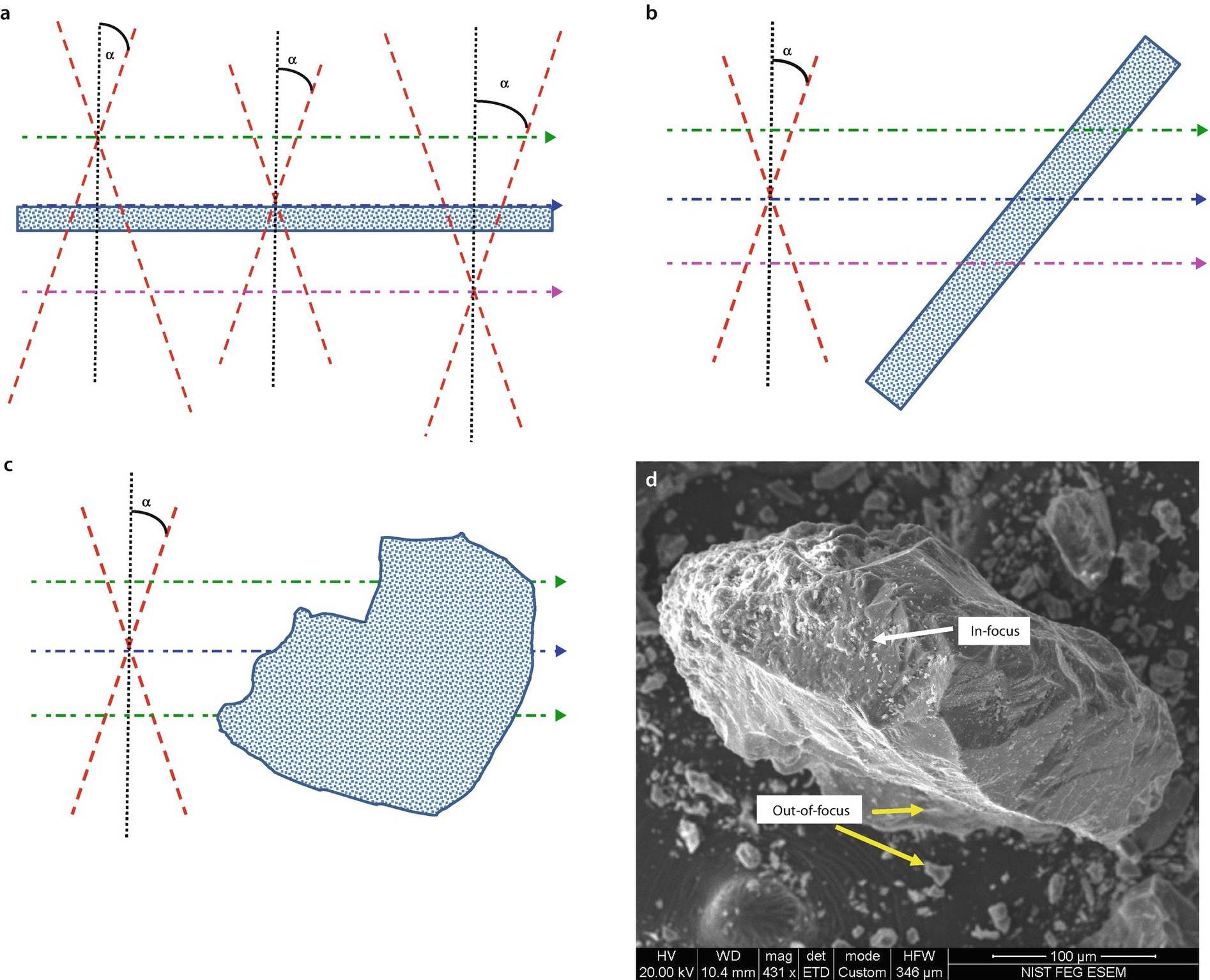

a Trivial example of optimal lens strength (focused at blue plane) and defocusing caused by selecting the objective lens strength too high (focused at green plane) and too low (focused at magenta plane) relative to the specimen surface. b Effect of a tilted planar surface. The beam is scanned with fixed objective lens strength, so that different beam diameters encounter the specimen at different distances along the optic axis. c Effects similar to ◘ Fig. 6.11b but for a three-dimensional specimen of arbitrary shape. d An imaging situation corresponding to ◘ Fig. 6.11c: coated fragments of Mt. St. Helens ash mounted on conducting tape and imaged under high vacuum at E 0 = 20 keV with an E–T (positive) detector

Defocusing is also encountered when the specimen has features that extend along the optic axis. For example, defocusing may be encountered when planar specimens are tilted or rough topographic specimens are examined, even at low magnifications, i.e., large scanned areas, as illustrated schematically in ◘ Fig. 6.11b, c. In these situations, the diameter of the converged beam that encounters the specimen depends on the distance of the feature from the bottom of the objective lens and the convergence angle of the beam, α. Because the beam is focused to a minimum diameter at a specific distance from the objective lens, the working distance W, any feature of the specimen that the scanned beam encounters at any other distance along the optic axis will inevitably involve a larger beam diameter, which can easily exceed the sampling footprint of the BSE and SE. ◘ Figure 6.11d shows an image of Mt. St. Helens volcanic ash particles where the top of the large particle is in good focus, but the focus along the sides of the particles deteriorates into obvious blurring, as also occurs for the small particles dispersed around the large particle on the conductive tape support. This defocus situation can only be improved by reducing the convergence angle, α, as described in Depth-of-Field Mode operation.

6.5 Making Measurements on Surfaces With Arbitrary Topography: Stereomicroscopy

SEM/E–T (positive) image of a metal fracture surface. The red arrows designate members of a class of flat objects embedded in this surface

6.5.1 Qualitative Stereomicroscopy

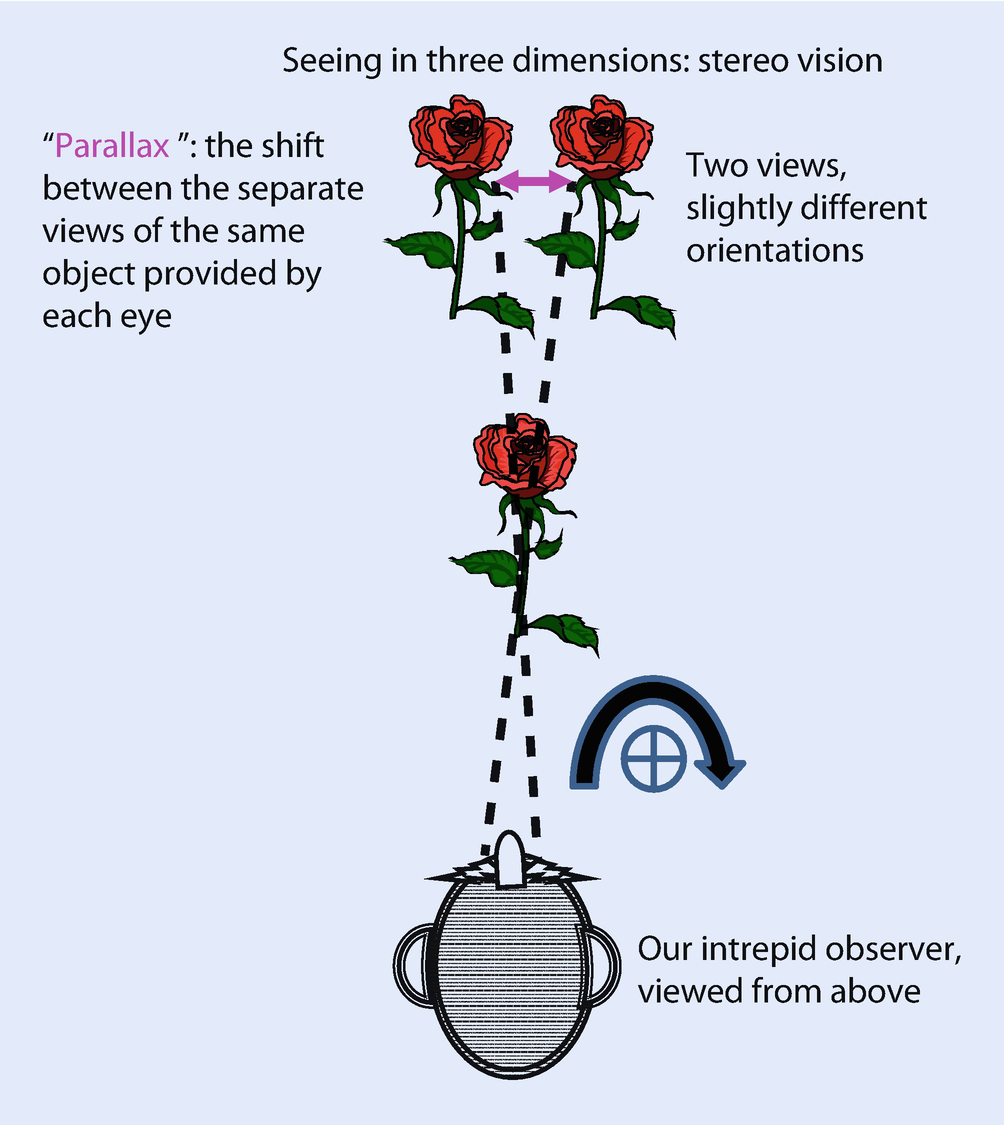

Schematic illustration of an observer’s creation of a stereo view of an object. Note that the parallax (shift between the two views) is across a vertical axis

6.5.1.1 Fixed beam, Specimen Position Altered

Parallax can be created by changing the specimen tilt relative to the optic axis (beam) by recording two images with a difference in tilt angle ranging from 2° to 10°. The specific value depends on the degree of topography of the specimen, and the optimum choice may require a trial-and-error approach. Weak topography will generally require a larger tilt difference to create a suitable three-dimensional effect. However, if the tilt angle difference between the images is made too large, it may not be possible for a viewer to successfully fuse the images and visualize the topography, especially for large-scale topography.

- 1.

Determine where the tilt axis lies in the SEM image. The eventual images must be presented to the viewer with horizontal parallax (i.e., all the shift between the two images must be across a vertical axis), so the tilt axis must be oriented vertically. The images can be recorded and rotated appropriately within image processing software such as ImageJ-Fiji, or the scan rotation function of the SEM can be used to orient the tilt axis along the vertical. In either case, note the location of the Everhart–Thornley detector in the image, which will provide the general sense of illumination. Ideally, the position of the E–T detector should be at the top of the image. However, after image rotation to orient the tilt axis vertically, the effective position of the Everhart-Thornley detector is likely to be different from this ideal 12-o’clock position (top center of image).

- 2.

Record an image of the area of interest at the low tilt angle, for example, stage tilt = 0°.

- 3.

Using this image as a reference, increase the tilt angle to the desired value, e.g., stage tilt = 5°, while maintaining the location of the field of view. Depending on the mechanical sophistication of the specimen stage, changing the tilt may cause the field of view to shift laterally, requiring continual relocation of the desired field of view during the tilting process to avoid losing the area of interest, especially at high magnification on specimens with complex topography.

- 4.

The vertical position of the specimen may also shift during tilting. To avoid introducing rotation in the second (high tilt image) by changing the objective lens strength to re-focus, the vertical stage motion (z-axis) should be used to refocus the image. After careful adjustment of the x-y-z position of the stage using the low tilt image to locate the area of interest, record this high tilt image.

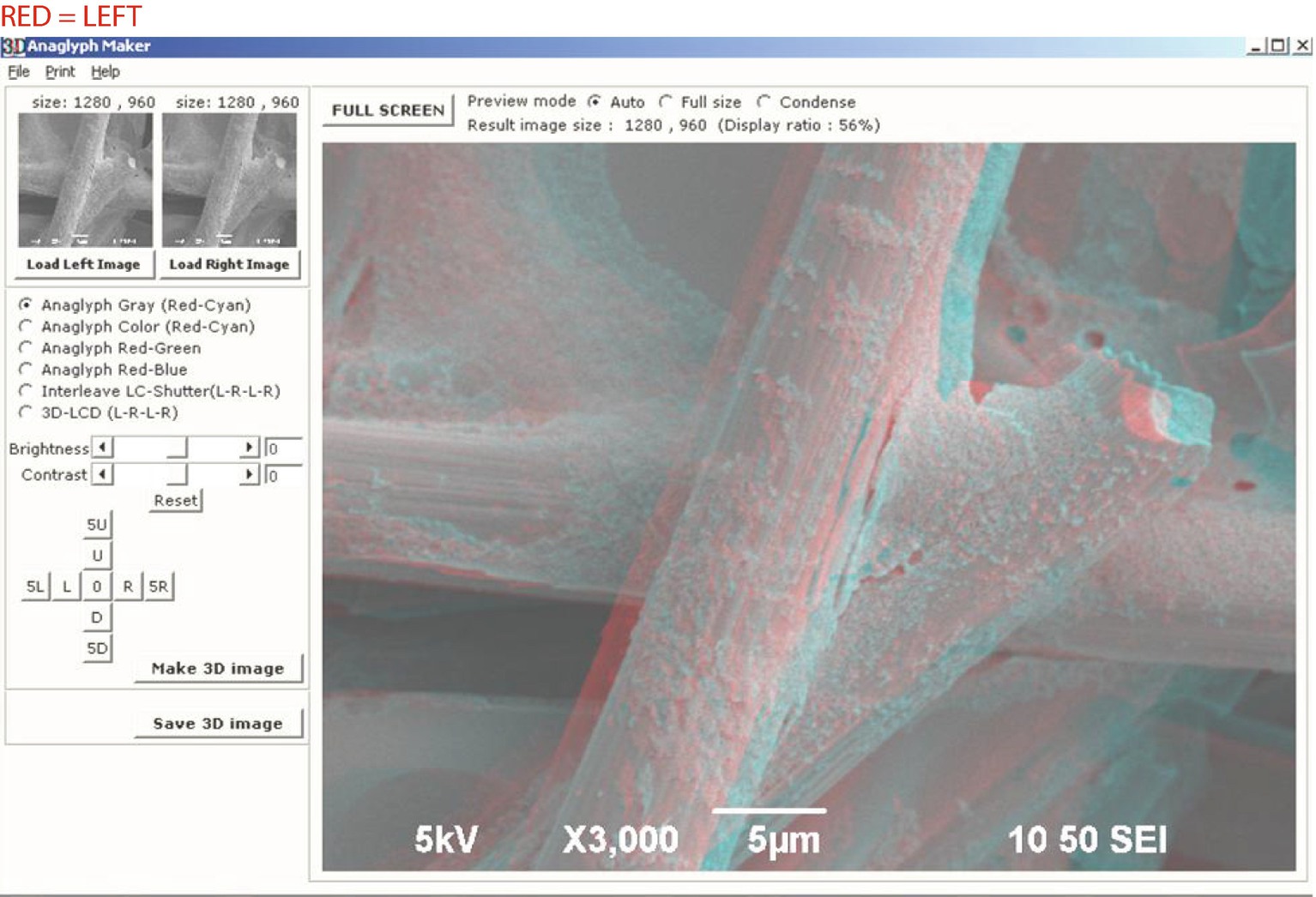

- 5.Within the image-processing software, assign the low tilt image to the RED image channel and the high tilt image to the CYAN (GREEN-BLUE channels combined, or the individual GREEN or BLUE image channels, depending on the type of anaglyph viewing filters available). Apply the image fusion function to create the stereo image, and view this image display with appropriate red (left eye) and blue (right eye) glasses. Note: The image-processing software may allow fine scale adjustments (shifts and/or rotations) to improve the registration of the images. This procedure is illustrated in ◘ Fig. 6.14 for the “Anaglyph Maker STEREOEYE” software (► http://www.stereoeye.jp/index_e.html). Examples of “stereo pairs” created in this manner are shown in ◘ Fig. 6.15 (a particle of ash from the Mt. St. Helens eruption) and ◘ Fig. 6.16 (gypsum crystals from cement).

Fig. 6.14

Fig. 6.14Illustration of the main page of the “Anaglyph Maker STEREOEYE” software (► http://www.stereoeye.jp/index_e.html) showing the windows where the left (low tilt) and right (high tilt) SEM/E–T (positive) images are selected and the resulting anaglyph (convention: red filter for the left eye). Note that brightness and contrast and fine position adjustments are available to the user. Specimen: ceramic fibers, coated with Au-Pd; E 0 = 5 keV

Fig. 6.15

Fig. 6.15Anaglyph stereo presentation of SEM/E–T(positive) images (E 0 = 20 keV) of a grain of Mt. St. Helens volcanic ash prepared by the stage tilting stereo method

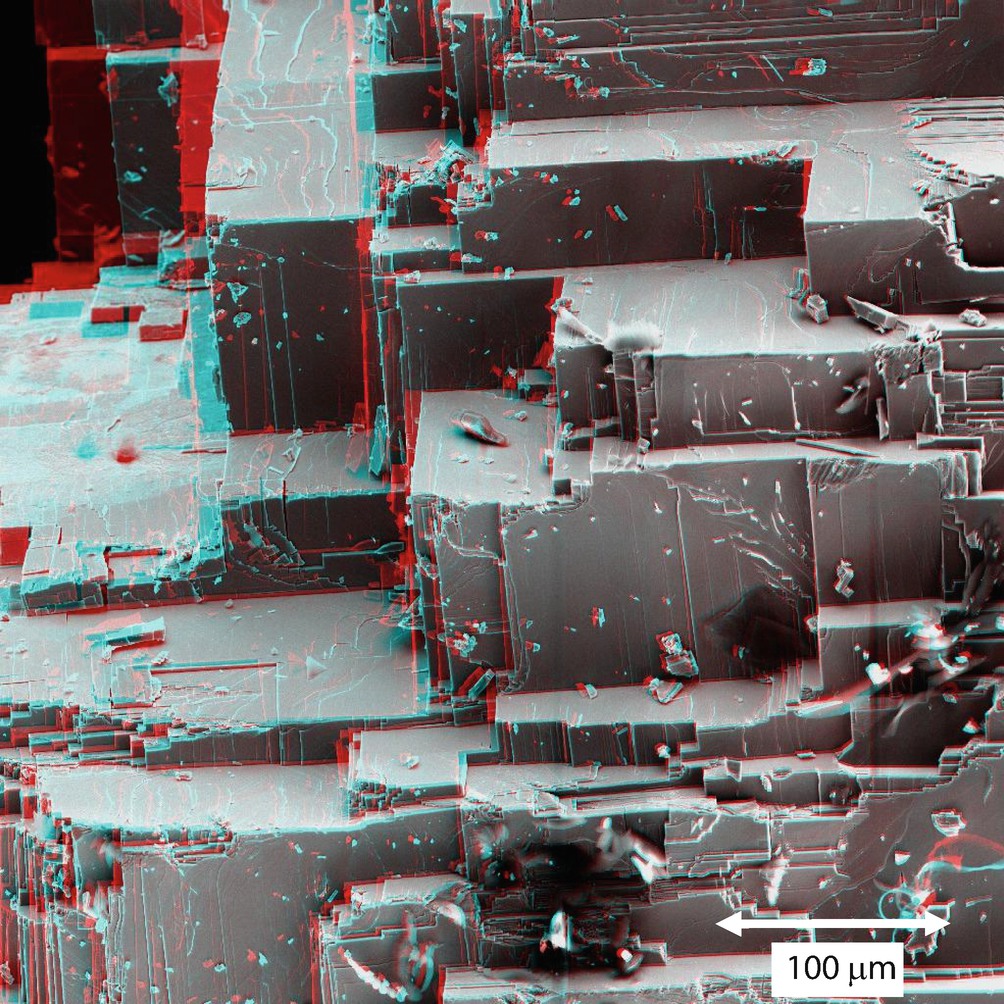

Fig. 6.16

Fig. 6.16Anaglyph stereo presentation of SEM/E–T(positive) images (E 0 = 20 keV) of a grain of gypsum crystals prepared by the stage tilting stereo method

Note

While usually successful, this SEM stereomicroscopy “recipe” may not produce the desired stereo effect on your particular instrument. Because of differing conventions for labeling tilt motions or due to unexpected image rotation applied in the software, the sense of the topography may be reversed (e.g., a topographic feature that is an “inner” falsely becomes an “outer” and vice versa). It is good practice when first implementing stereomicroscopy with an SEM to start with a simple specimen with known topography such as a coin with raised lettering or a scratch on a flat surface. Apply the procedure above and inspect the results to determine if the proper sense of the topography has been achieved in the resulting stereo pair. If not, be sure the parallax shift is horizontal, that is, across a vertical axis (if necessary, use software functions to rotate the images to vertically orient the tilt axis). If the tilt axis is vertical but the stereo pair still shows the wrong sense of the topography, try reversing the images so the “high tilt” image is now viewed by the left eye and the “low tilt” image viewed by the right eye. Once the proper procedure has been discovered to give the correct sense of the topography on a known test structure, follow this convention for future stereomicroscopy work. (Note: A small but significant fraction of observers find it difficult to fuse the images to form a stereo image.)

6.5.1.2 Fixed Specimen, Beam Incidence Angle Changed

Anaglyph stereo presentation of SEM/E–T(positive) images (E 0 = 15 keV) of a fractured galena crystal prepared by the beam tilting stereo method

Anaglyph stereo presentation of SEM/E–T(positive) images (E 0 = 15 keV) of a silver crystal prepared by the beam tilting stereo method

6.5.2 Quantitative Stereomicroscopy

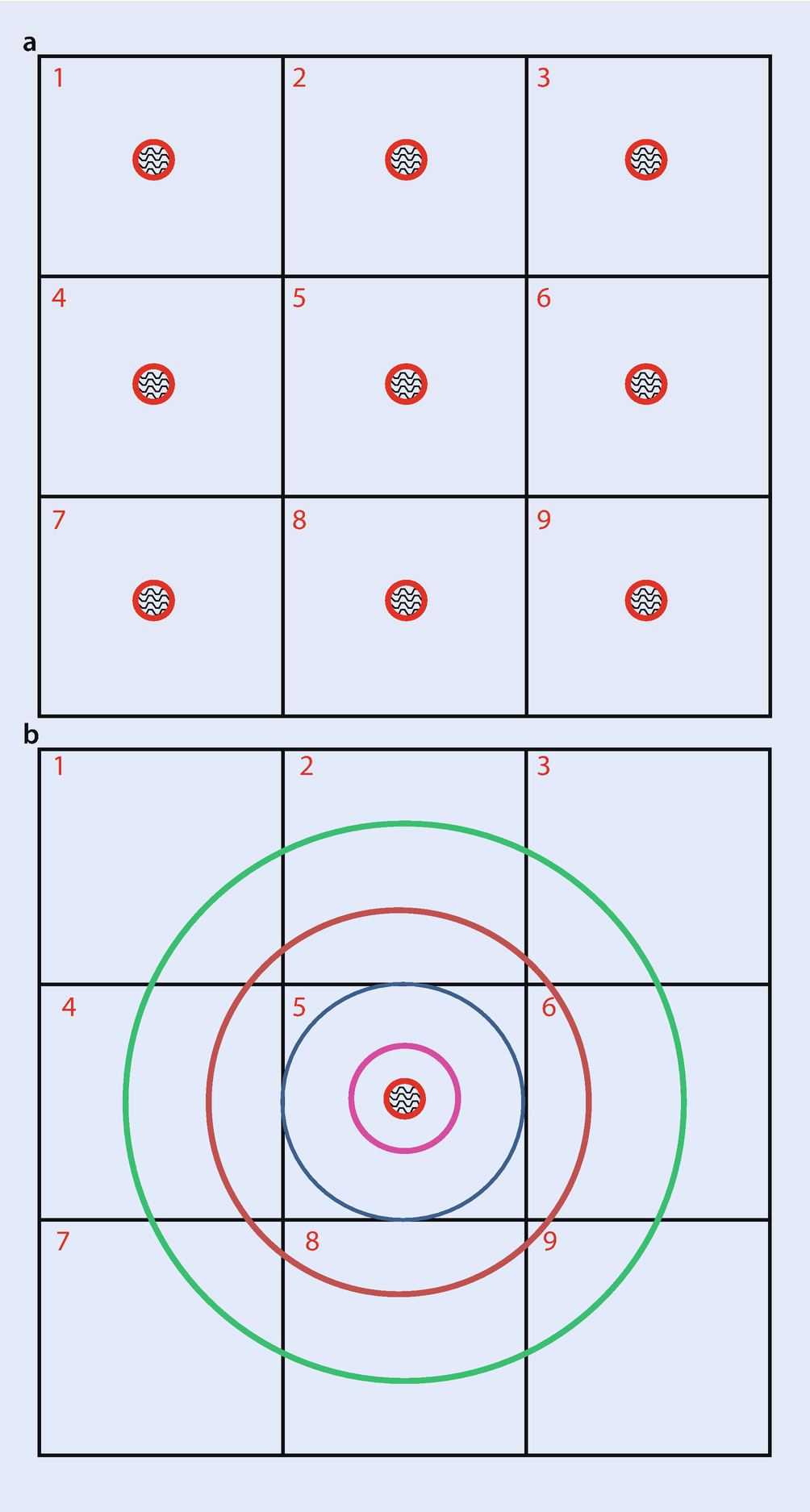

Schematic diagram of the procedure for making quantitative stereo measurements

- 1.The first step is to record a stereo pair with tilt angles θ1 and θ2 and with the tilt axis placed in a vertical orientation in the images. The difference in tilt angle between the members of the stereo pair is a critical parameter:

(6.4)

(6.4) - 2.

A set of orthogonal axes is centered on a recognizable feature, as shown in the schematic example in ◘ Fig. 6.19. This point will then be arbitrarily assigned the X-, Y-, Z-coordinates (0, 0, 0) and all subsequent height measurements will be with respect to this point. The axes are selected so that the y-axis is parallel to the tilt axis and the x-axis is perpendicular to the tilt axis.

- 3.For the feature of interest, the (X, Y)-coordinates are measured in the Left (X L, Y L) and Right (X R, Y R) members of the stereo pair using the calibrated distance marker. The parallax, P, of a feature is given by

(6.5)

(6.5)With this convention, points lying above the tilt axis will have positive parallax values P. Note that as an internal consistency check, Y L = Y R if the y-axis has been properly aligned with the tilt axis.

- 4.For SEM magnifications above a nominal value of 100×, the scan angle will be sufficiently small that it can be assumed that the scan is effectively moving parallel to the optic axis, which enables the use of simple formulas for quantification. With reference to the fixed point (0, 0, 0), the three-dimensional coordinates X 3, Y 3, Z 3 of the chosen feature are given by

![$$ {Z}_3=P/\left[2\ \sin\ \left(\varDelta \theta /2\right)\right] $$](../images/271173_4_En_6_Chapter/271173_4_En_6_Chapter_TeX_Equ6.png) (6.6)

(6.6) (6.7)(Note that Eq. (6.7) provides a self-consistency check for the X3 coordinate.)

(6.7)(Note that Eq. (6.7) provides a self-consistency check for the X3 coordinate.) (6.8)

(6.8)Note that if the measured coordinates y L and y R are not the same then this implies that the tilt axis is not accurately parallel to Y and the axes must then be rotated to correct this error.

By measuring any two points with coordinates, (X M, Y M, Z M) and (X N, Y M, Z M), the length L of the straight line connecting the points is given by![$$ L=\mathrm{SQRT}\left[{\left({X}_{\mathrm{M}}-{X}_{\mathrm{N}}\right)}^2+{\left({Y}_{\mathrm{M}}-{Y}_{\mathrm{N}}\right)}^2+{\left({Z}_{\mathrm{M}}-{Z}_{\mathrm{N}}\right)}^2\right] $$](../images/271173_4_En_6_Chapter/271173_4_En_6_Chapter_TeX_Equ9.png) (6.9)

(6.9)

6.5.2.1 Measuring a Simple Vertical Displacement

a Stereo pair of a machined screw thread—SEM/E–T(positive) images; E 0 = 20 keV. b Stereo pair with superimposed axes for measurement of coordinates needed for quantitative stereomicroscopy calculations

![$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{Z}_3=P/\left[2\ \sin\ \left(\varDelta \theta /2\right)\right]\ \\ {}=-54\ \mu \mathrm{m}/\left[2\ \sin \left({5}^{{}^{\circ}}/2\right)\right]\ \\ {}=-619\ \mu \mathrm{m}\end{array}} $$](../images/271173_4_En_6_Chapter/271173_4_En_6_Chapter_TeX_Equ11.png)

- 1.

Scale calibration error: with the careful use of a primary or secondary dimensional artifact, this uncertainty contribution can be reduced to 1 % relative or less.

- 2.

Measurement of the feature individual coordinates: The magnitude of this uncertainty contribution depends on how well the position of a feature can be recognized and on the separation of the features of interest. By selecting a magnification such that the features whose vertical separation is to be measured span at least half of the image field, the uncertainty in the individual coordinates should be approximately 1 % relative, and in the difference of X-coordinates (X L–X R) about 2 % relative. For closely spaced features, the magnitude of this uncertainty contribution will increase.

- 3.

Uncertainty in the individual tilt settings: The magnitude of this uncertainty is dependent on the degree of backlash in the mechanical stage motions. Backlash effects can be minimized by selecting the initial (low) tilt value to correspond to a well-defined detent position if the mechanical stage is so designed, such as a physical stop at 0° tilt. With a properly maintained mechanical stage, the uncertainty in the tilt angle difference Δθ is estimated to be approximately 2 % for Δθ = 50, with the relative uncertainty increasing for smaller values of Δθ.

- 4.

Considering all of these sources of uncertainty, the measurement should be assigned an overall uncertainty of ±5 % relative.

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.