7.1 Information in SEM Images

- 1.

Number effects. Number effects refer to contrast which arises as a result of different numbers of electrons leaving the specimen at different beam locations in response to changes in the specimen characteristics at those locations.

- 2.

Trajectory effects. Trajectory effects refer to contrast resulting from differences in the paths the electrons travel after leaving the specimen.

- 3.

Energy effects. Energy effects occur when the contrast is carried by a certain portion of the backscattered electron or secondary electron energy distribution. For example, the high-energy backscattered electrons are generally the most useful for imaging the specimen using contrast mechanisms such as atomic number contrast or crystallographic contrast. Low-energy secondary electrons are likely to escape from a shallow surface region of a specimen and convey surface information.

7.2 Interpretation of SEM Images of Compositional Microstructure

7.2.1 Atomic Number Contrast With Backscattered Electrons

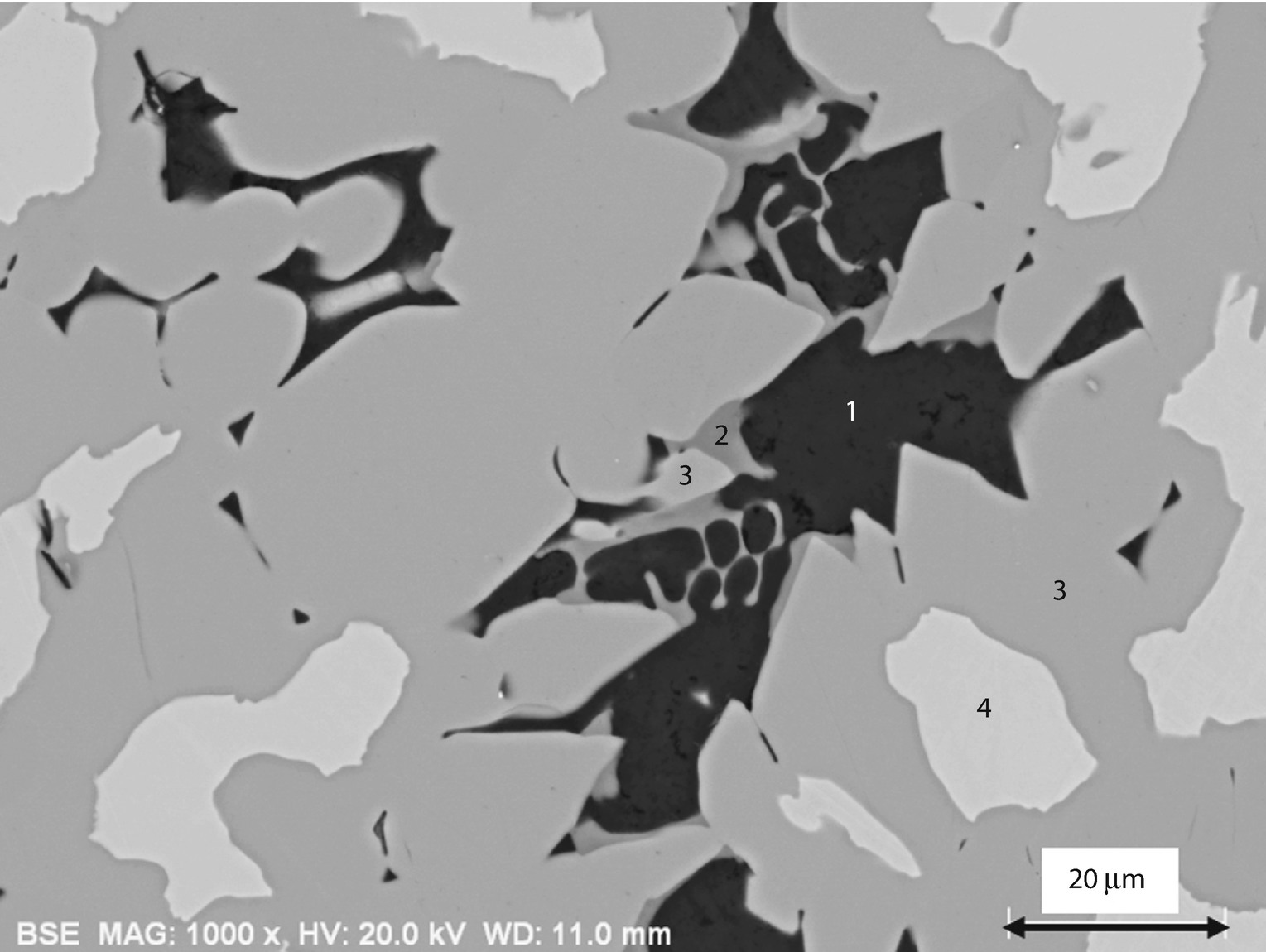

Raney nickel; E 0 = 20 keV; semiconductor BSE detector (SUM mode)

Raney nickel alloy (measured composition, calculated average atomic number, backscatter coefficient, and atomic number contrast across the boundary between adjacent phases)

Phase | Al (mass frac) | Fe (mass frac) | Ni (mass frac) | Z av | Calculated, η | Contrast |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 0.9874 | 0.0003 | 0.0123 | 13.2 | 0.155 | |

2 | 0.6824 | 0.0409 | 0.2768 | 17.7 | 0.204 | 1–2 0.24 |

3 | 0.5817 | 0.0026 | 0.4155 | 19.3 | 0.22 | 2–3 0.073 |

4 | 0.4192 | 0.0007 | 0.5801 | 21.7 | 0.243 | 3–4 0.095 |

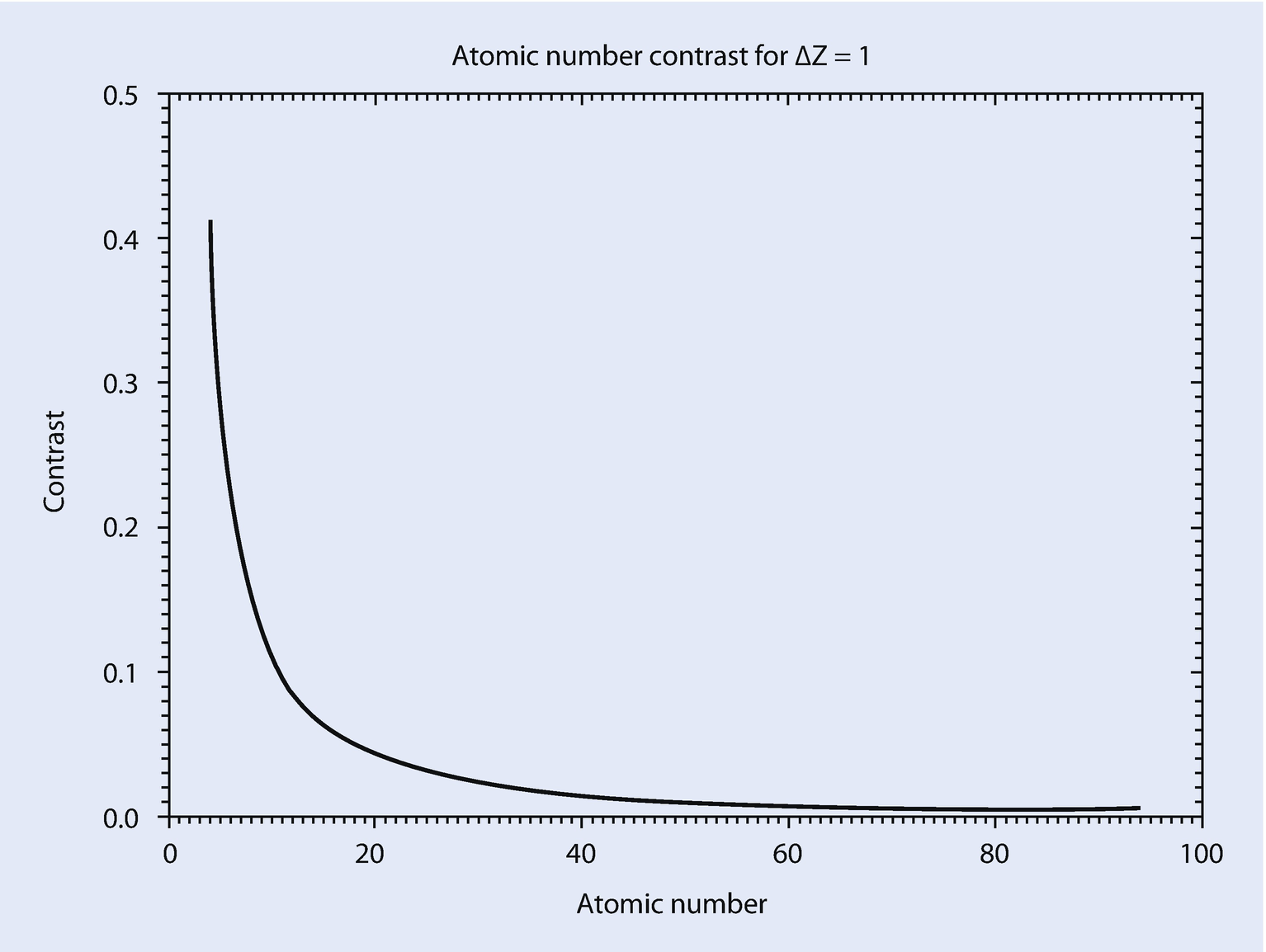

7.2.2 Calculating Atomic Number Contrast

An SEM is typically equipped with a “dedicated backscattered electron detector” (e.g., semiconductor or passive scintillator) that produces a signal, S, proportional to the number of BSEs that strike it and thus to the backscattered electron coefficient, η, of the specimen. Note that other factors, such as the energy distribution of the BSEs, can also influence the detector response.

Atomic number contrast for pure elements with ΔZ = 1

7.2.3 BSE Atomic Number Contrast With the Everhart–Thornley Detector

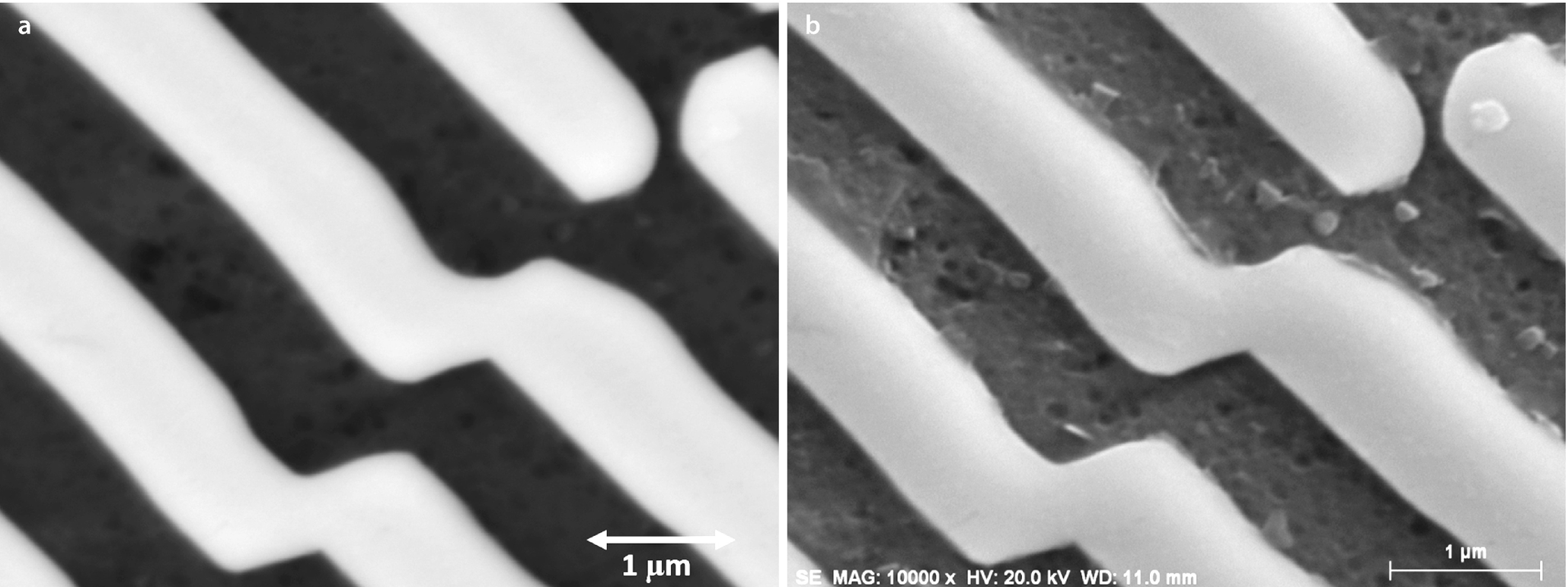

Aligned Al-Cu eutectic; E 0 = 20 keV: a semiconductor BSE detector (SUM mode); b Everhart–Thornley detector (positive bias)

For both the dedicated semiconductor BSE detector and the E–T detector, the higher atomic number regions appear brighter than the lower atomic number regions, as independently confirmed by energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry of both materials. However, the semiconductor BSE detector actually enhances the atomic number contrast over that estimated from the composition (Al-0.02Cu, η = 0.155; CuAl2, η = 0.232, which gives C tr = 0.33). The semiconductor detector shows increased response from higher energy backscattered electrons, which are produced in greater relative abundance from Cu compared to Al, thus enhancing the difference in the measured signals. The response of the Everhart-Thornley detector (positive bias) to BSEs is more complex. The BSEs that directly strike the scintillator produce a greater response with increasing energy. However, this component is small compared to the BSEs that strike the objective lens pole piece and chamber walls, where they are converted to SE3 and subsequently collected. For these remote BSEs, the lower energy fraction actually create SEs more efficiently.

7.3 Interpretation of SEM Images of Specimen Topography

- 1.

The backscattered electron coefficient shows a strong dependence on the surface inclination, η versus θ. This effect contributes a number component to the observed contrast.

- 2.

Backscattering from a surface perpendicular to the beam (i.e., 0° tilt) is directional and follows a cosine distribution η(φ) ≈ cos φ (where φ is an angle measured from the surface normal) that is rotationally symmetric around the beam. This effect contributes a trajectory component of contrast.

- 3.

Backscattering from a surface tilted to an angle θ becomes more highly directional and asymmetrical as θ increases, tending to peak in the forward scattering direction. This effect contributes a trajectory component of contrast.

- 4.

The secondary electron coefficient δ is strongly dependent on the surface inclination, δ(θ) ≈ sec θ, increasing rapidly as the beam approaches grazing incidence. This effect contributes a number component of contrast.

- 1.

Observer’s Point-of-View: The microscopist views the specimen features as if looking along the electron beam.

- 2.Apparent Illumination of the Scene:

- a.

The apparent major source of lighting of the scene comes from the position of the electron detector.

- b.

Depending on the detector used, there may appear to be minor illumination sources coming from other directions.

- a.

7.3.1 Imaging Specimen Topography With the Everhart–Thornley Detector

SEM images of specimen topography collected with the Everhart–Thornley (positive bias) detector (Everhart and Thornley 1960) are surprisingly easy to interpret, considering how drastically the imaging technique differs from ordinary human visual experience: A finely focused electron beam steps sequentially through a series of locations on the specimen and a mixture of the backscattered electron and secondary electron signals, subject to the four number and trajectory effects noted above that result from complex beam–specimen interactions, is used to create the gray-scale image on the display. Nevertheless, a completely untrained observer (even a young child) can be reasonably expected to intuitively understand the general shape of a three-dimensional object from the details of the pattern of highlights and shading in the SEM/E–T (positive bias) image. In fact, the appearance of a three-dimensional object viewed in an SEM/E–T (positive bias) image is strikingly similar to the view that would be obtained if that object were viewed with a conventional light source and the human eye, producing the so-called “light-optical analogy.” This situation is quite remarkable, and the relative ease with which SEM/E–T (positive bias) images can be utilized is a major source of the utility and popularity of the SEM. It is important to understand the origin of this SEM/E–T (positive bias) light-optical analogy and what pathological effects can occur to diminish or destroy the effect, possibly leading to incorrect image interpretation of topography.

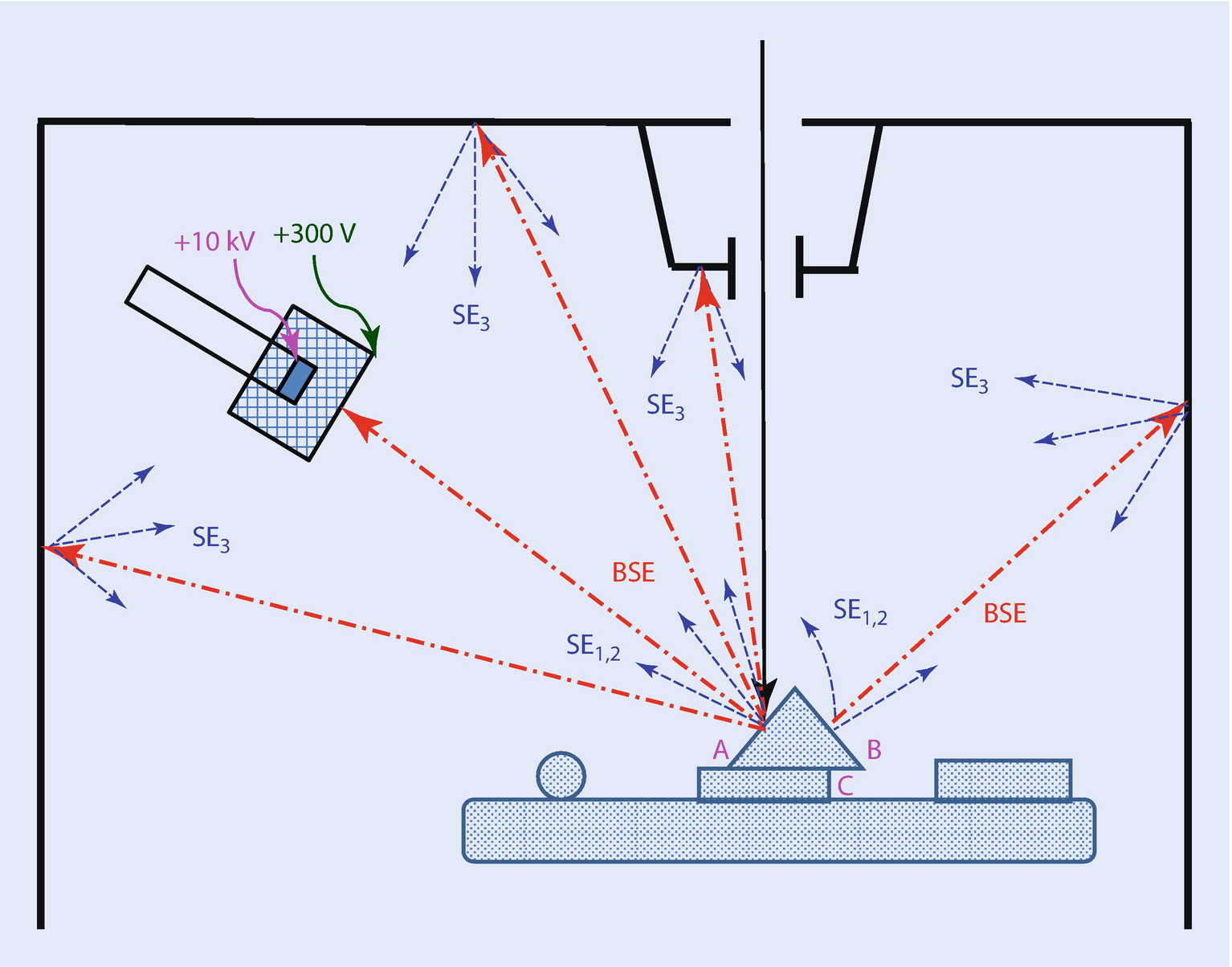

Schematic illustration of the various sources of signals generated from topography: BSEs, SE1 and SE2, and remote SE3 and collection by the Everhart–Thornley detector

7.3.2 The Light-Optical Analogy to the SEM/E–T (Positive Bias) Image

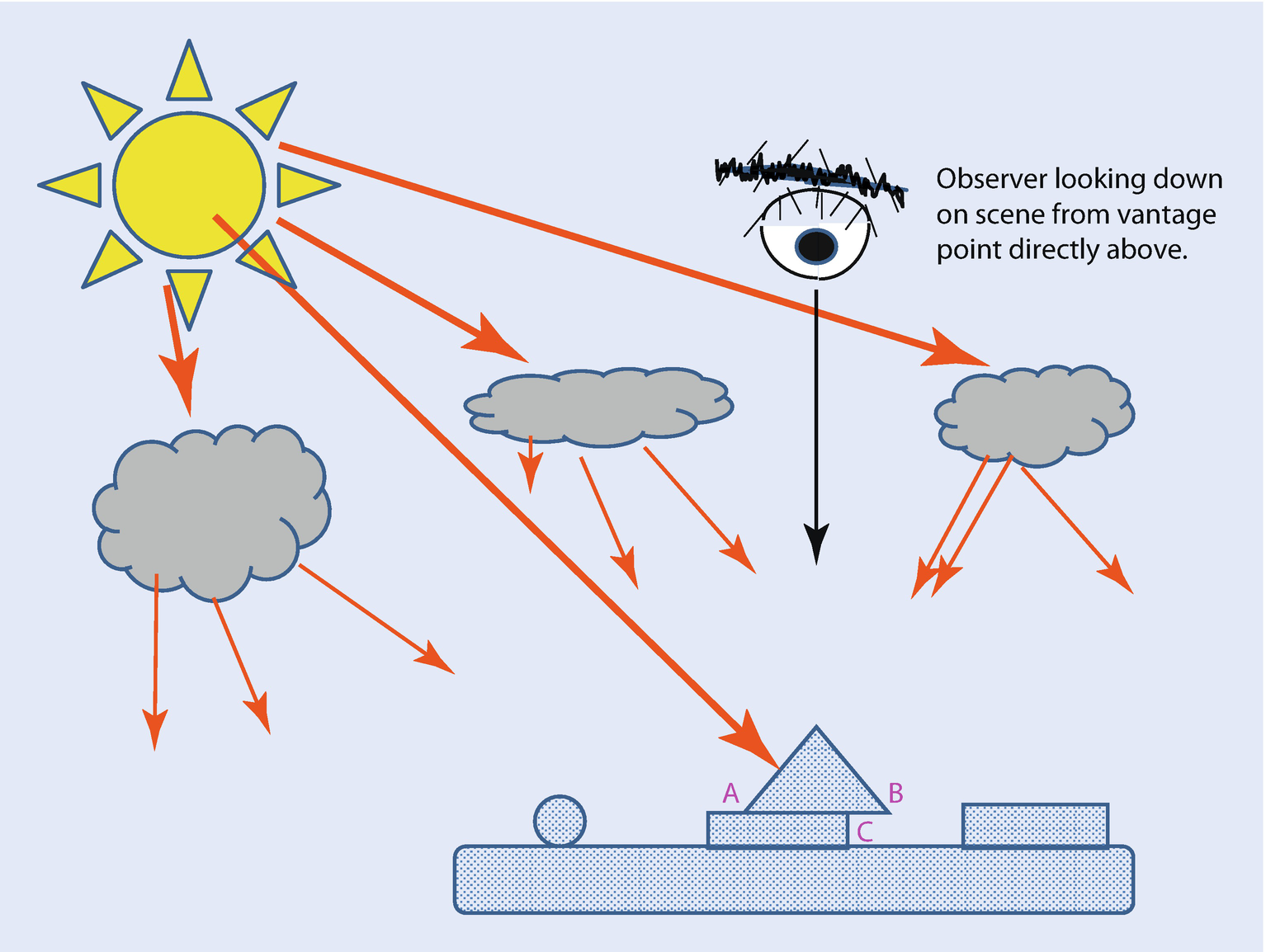

Human visual experience equivalent to the observer position and lighting situation of the Everhart–Thornley (positive bias) detector

- 1.

The human observer’s eye, which has a very sharply defined line-of-sight, is matched in characteristic by the electron beam, which presents a very narrow cone angle of rays: thus, the observer of an SEM image is effectively looking along the beam, and what the beam can strike is what can be observed in an image.

- 2.

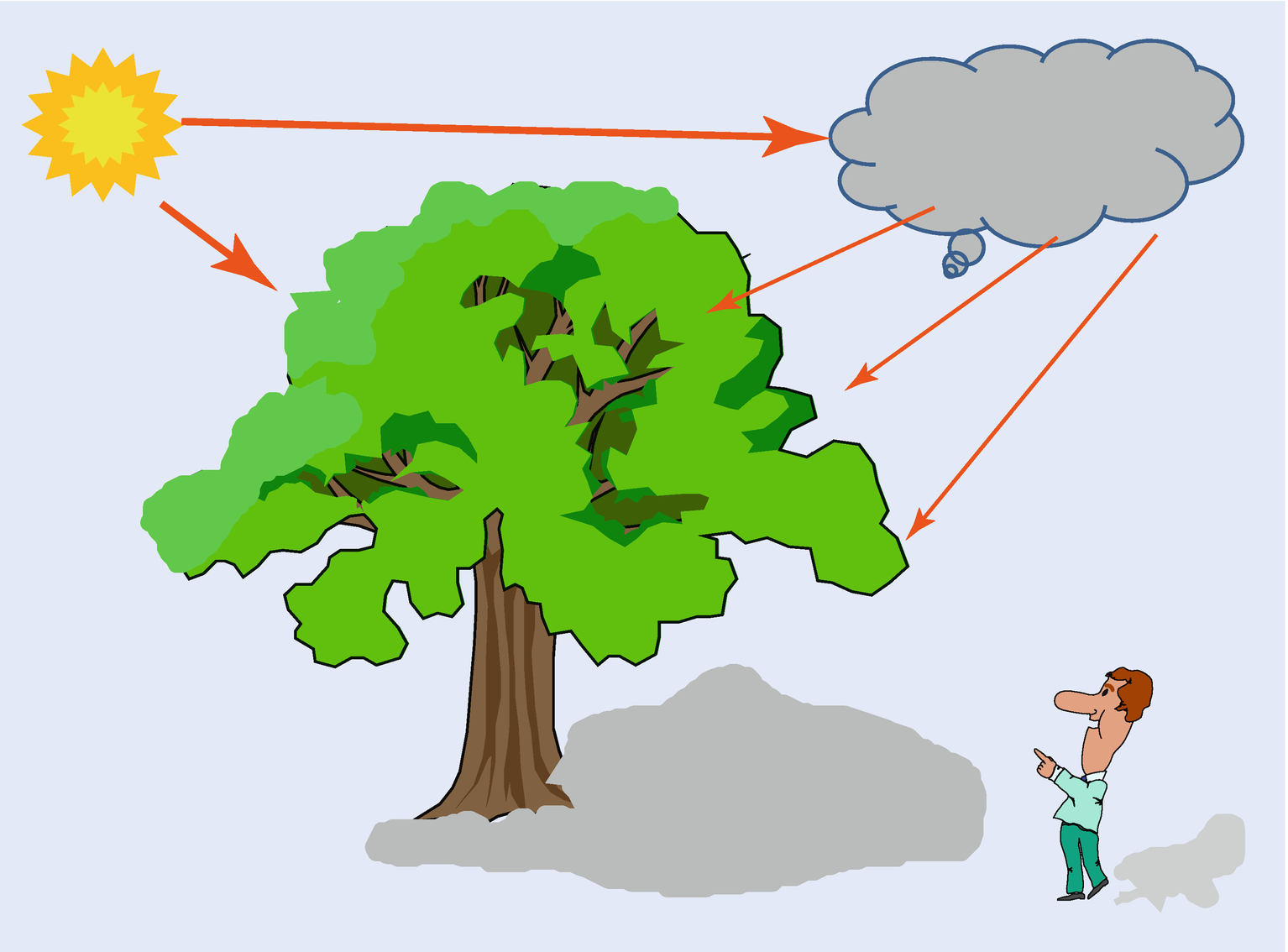

The illumination of an outdoor scene by the Sun consists of a direct component (direct rays that strongly light those surfaces that they strike) and an indirect component (diffuse scattering of the Sun’s rays from clouds and the atmosphere, weakly illuminating the scene from all angles). For the E–T detector (positive bias), there is a direct signal component that acts like the Sun (BSEs emitted by the specimen into the solid angle defined by the scintillator, as well as SE1 and SE2 directly collected from the specimen) and an indirect component that acts like diffuse illumination (SE3 collected from all surfaces struck by BSEs).

Though counterintuitive, in the SEM the detector is the apparent source of illumination while the observer looks along the electron beam.

7.3.2.1 Establishing a Robust Light-Optical Analogy

We have evolved in a world of top lighting. Features facing the Sun are brightly illuminated, while features facing away are shaded but receive some illumination from atmospheric scattering. Bright = facing upwards

7.3.2.2 Getting It Wrong: Breaking the Light-Optical Analogy of the Everhart–Thornley (Positive Bias) Detector

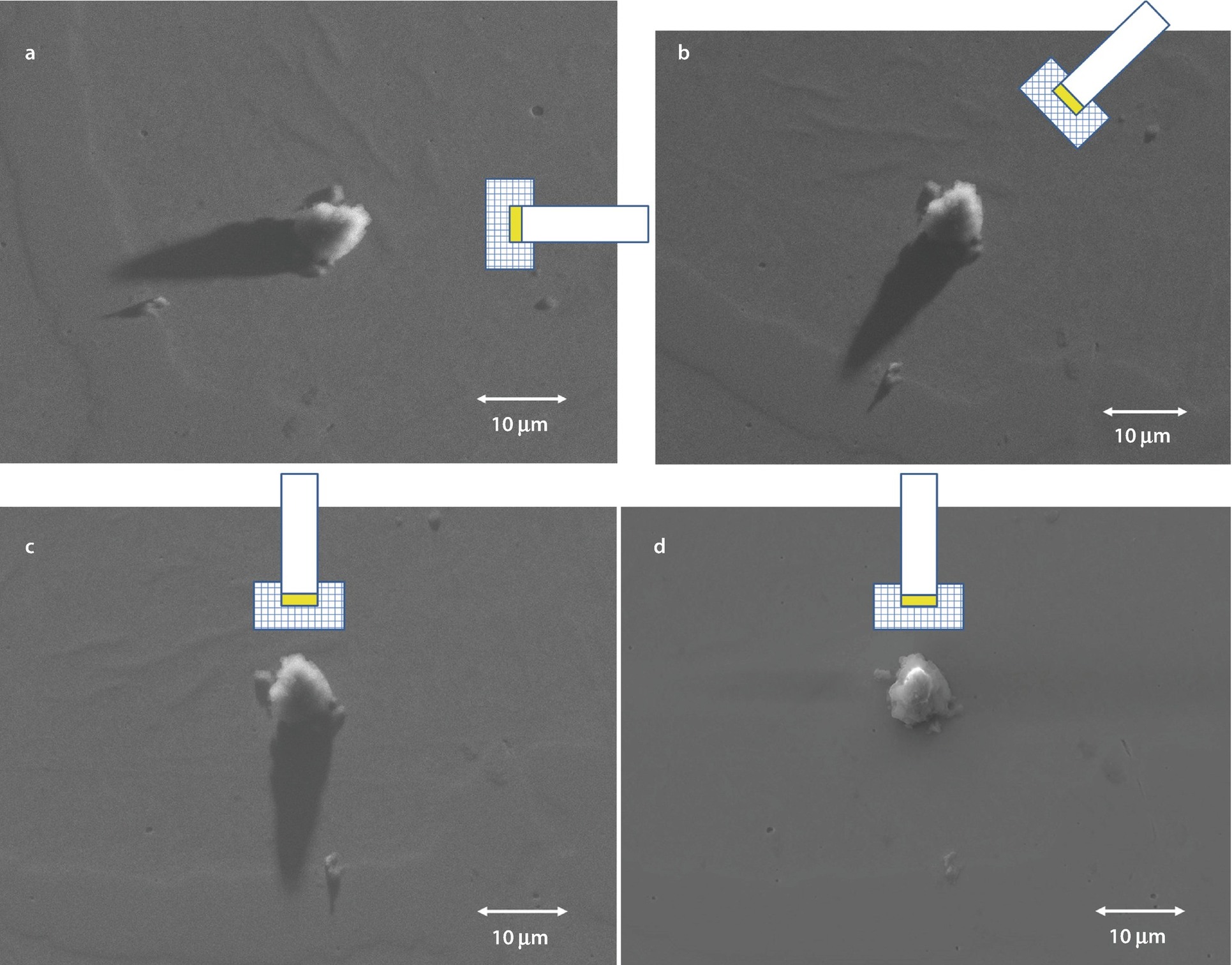

a SEM image of a particle on a surface as prepared with the E–T (negative bias) detector in the 90° clockwise position shown; E 0 = 20 keV. Note strong shadowing pointing away from E–T . b SEM image of a particle on a surface as prepared with the E–T (negative bias) detector in the 45° clockwise position shown; E 0 = 20 keV. Note strong shadowing pointing away from E–T . c SEM image of a particle on a surface as prepared with the E–T (negative bias) detector in the 0° clockwise (12 o’clock) position shown; E 0 = 20 keV. Note strong shadowing pointing away from E–T . d SEM image of a particle on a surface as prepared with the E–T (positive bias) detector in the 0° clockwise (12 o’clock) position shown; E 0 = 20 keV. Note lack of shadowing but bright surface facing the E–T (positive bias) detector

Note that physically rotating the specimen stage to change the angular relation of the specimen relative to the E–T (or any other) detector does not change the location of the apparent source of illumination in the displayed image. Rotating the specimen stage changes which specimen features are directed toward the detector, but the scan orientation on the displayed image determines the relative position of the detector in the image presented to the viewer and the apparent direction of the illumination.

7.3.2.3 Deconstructing the SEM/E–T Image of Topography

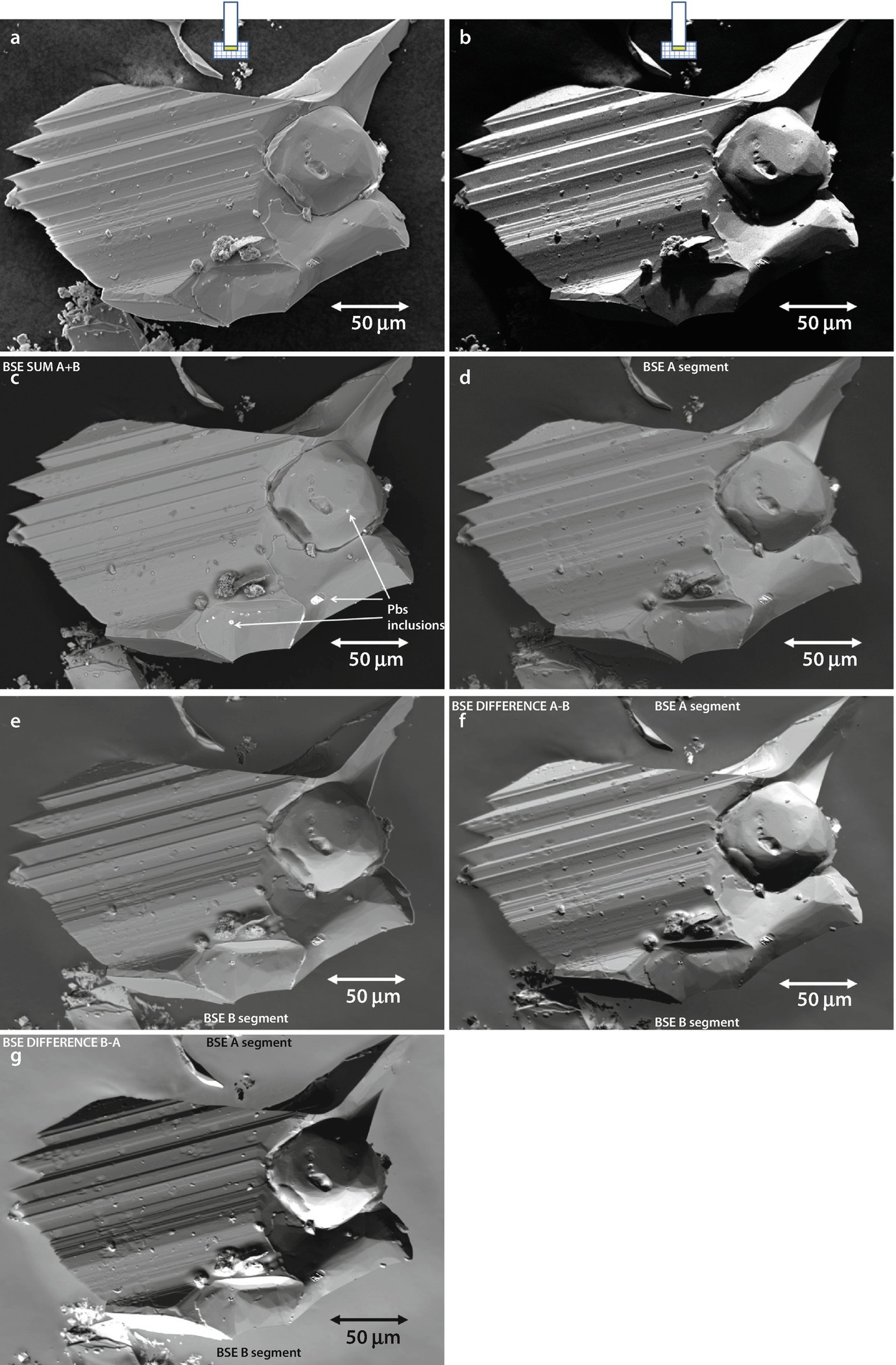

a SEM/E–T (positive bias) image of a fractured fragment of pyrite; E 0 = 20 keV. b SEM/E–T (negative bias) image of a fractured fragment of pyrite; E 0 = 20 keV. c SEM/BSE (A + B) SUM-mode image of a fractured fragment of pyrite; E 0 = 20 keV. d SEM/BSE (A segment) image (detector at top of image field) of a fractured fragment of pyrite (FeS2); E 0 = 20 keV. e SEM/BSE (B segment) image (detector at bottom of image field) of a fractured fragment of pyrite (FeS2); E 0 = 20 keV. f SEM/BSE (A−B) image (detector DIFFERENCE image) of a fractured fragment of pyrite (FeS2); E 0 = 20 keV. g SEM/BSE (B−A) image (detector DIFFERENCE image) of a fractured fragment of pyrite (FeS2); E 0 = 20 keV

7.3.3 Imaging Specimen Topography With a Semiconductor BSE Detector

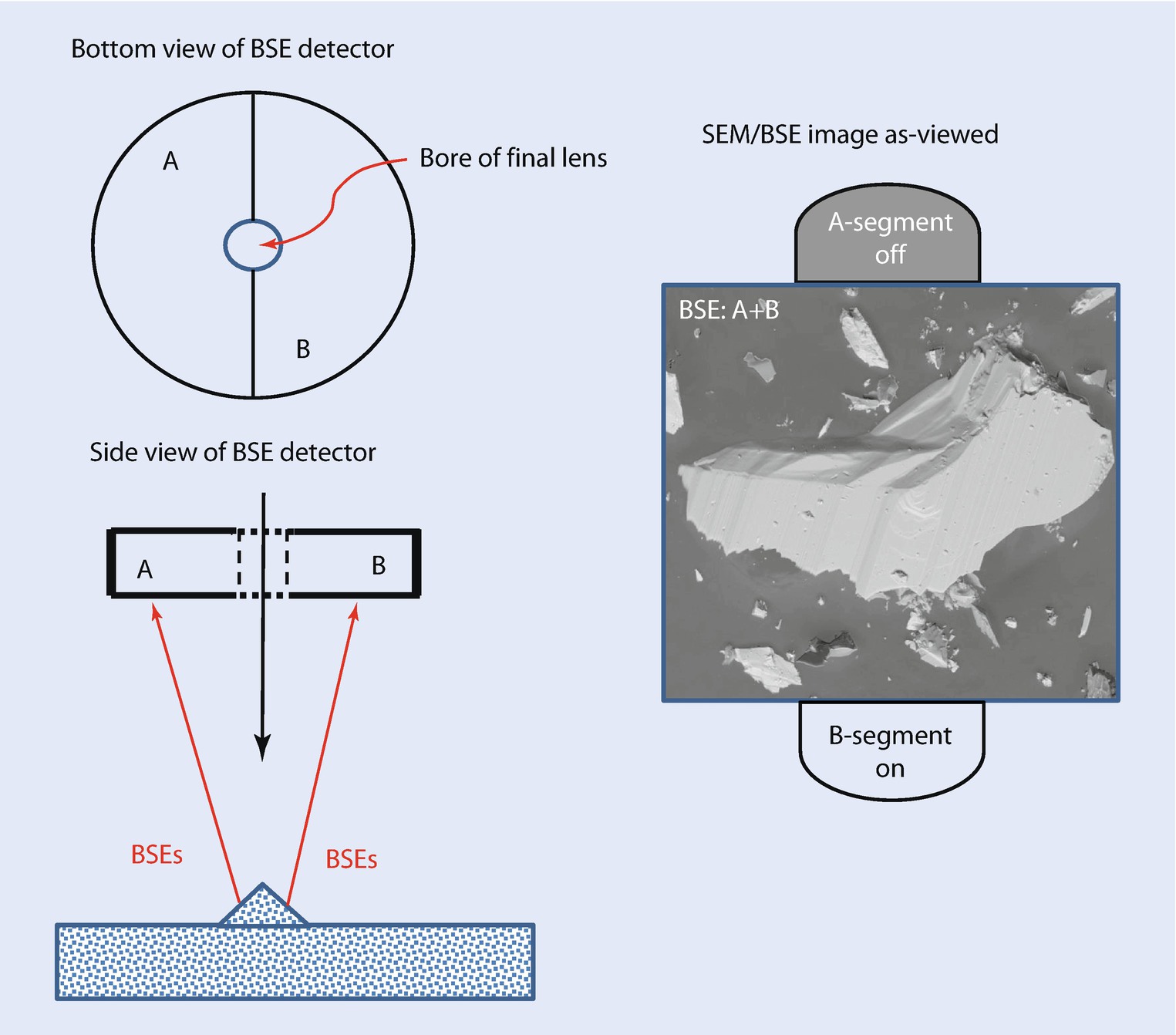

Schematic illustration of a segmented annular semiconductor BSE detector

7.3.3.1 SUM Mode (A + B)

The two-segment semiconductor BSE detector operating in the summation (A + B) mode was used to image the same pyrite specimen previously imaged with the E–T (positive bias) and E–T (negative bias), as shown in ◘ Fig. 7.8c. The placement of the large solid angle BSE is so close to the primary electron beam that it creates the effect of apparent wide-angle illumination that is highly directional along the line-of-sight of the observer, which would be the light-optical equivalent of being inside a flashlight looking along the beam. With such directional illumination along the observer’s line-of-sight, the brightest topographic features are those oriented perpendicular to the line-of-sight, while tilted surfaces appear darker, resulting in a substantially different impression of the topography of the pyrite specimen compared to the E–T (positive bias) image in ◘ Fig. 7.8a. The large solid angle of the detector acts to suppress topographic contrast, since local differences in the directionality of BSE emission caused by differently inclined surfaces are effectively eliminated when the diverging BSEs are intercepted by another part of the large BSE detector.

Another effect that is observed in the A + B image is the class of very bright inclusions which were subsequently determined to be galena (PbS) by X-ray microanalysis. The large difference in average atomic number between FeS2 (Z av = 20.7) and PbS (Z av = 73.2) results in strong atomic number (compositional) between the PbS inclusions and the FeS2 matrix. Although there is a significant BSE signal component in the E–T (positive bias) image in ◘ Fig. 7.8a, the topographic contrast is so strong that it overwhelms the compositional contrast.

7.3.3.2 Examining Images Prepared With the Individual Detector Segments

Some semiconductor BSE detector systems enable the microscopist to view BSE images prepared with the signal derived from the individual components of a segmented detector. As illustrated in ◘ Fig. 7.9 for a two-segment BSE detector, the individual segments effectively provide an off-axis, asymmetric illumination of the specimen. Comparing the A-segment and B-segment images of the pyrite crystal in ◘ Fig. 7.8d, e, the features facing each detector can be discerned and a sense of the topography can be obtained by comparing the two images. But note the strong effect of the apparent inversion of the sense of the topography in the B-segment image, where the illumination comes from the bottom of the field, compared to the A-segment image, where the illumination comes from the top of the field of view.

7.3.3.3 DIFFERENCE Mode (A−B)

The signals from the individual BSE detector segments “A” and “B” can be subtracted from each other, producing the image seen in ◘ Fig. 7.8f. Because the detector segments “A” and “B” effectively illuminate the specimen from two different directions, as seen in ◘ Fig. 7.8d, e, taking the difference A–B between the detector signals tends to enhance these directional differences, producing the strong contrast seen in ◘ Fig. 7.8f.

Note that when subtracting the signals the order of the segments in the subtraction has a profound effect on appearance of the final image. ◘ Figure 7.8g shows the image created with the order of subtraction reversed to give B–A. Because the observer is so strongly biased toward interpreting an image as if it must have top lighting, bright features are automatically interpreted as facing upward. This automatic assumption of top lighting has the effect for most viewers of ◘ Fig. 7.8g to strongly invert the apparent sense of the topography, so that protuberances in the A–B image become concavities in the B–A image. If BSE detector difference images are to be at all useful and not misleading, it is critical to determine the proper order of subtraction. A suitable test procedure is to image a specimen with known topography, such as the raised lettering on a coin or a particle standing on top of a flat surface.

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.