SEM images are subject to defects that can arise from a variety of mechanisms, including charging, radiation damage, contamination, and moiré fringe effects, among others. Image defects are very dependent on the specific nature of the specimen, and often they are anecdotal, experienced but not reported in the SEM literature. The examples described below are not a complete catalog but are presented to alert the microscopist to the possibility of such image defects so as to avoid interpreting artifact as fact.

9.1 Charging

Charging is one of the major image defects commonly encountered in SEM imaging, especially when using the Everhart–Thornley (positive bias) “secondary electron” detector, which is especially sensitive to even slight charging.

9.1.1 What Is Specimen Charging?

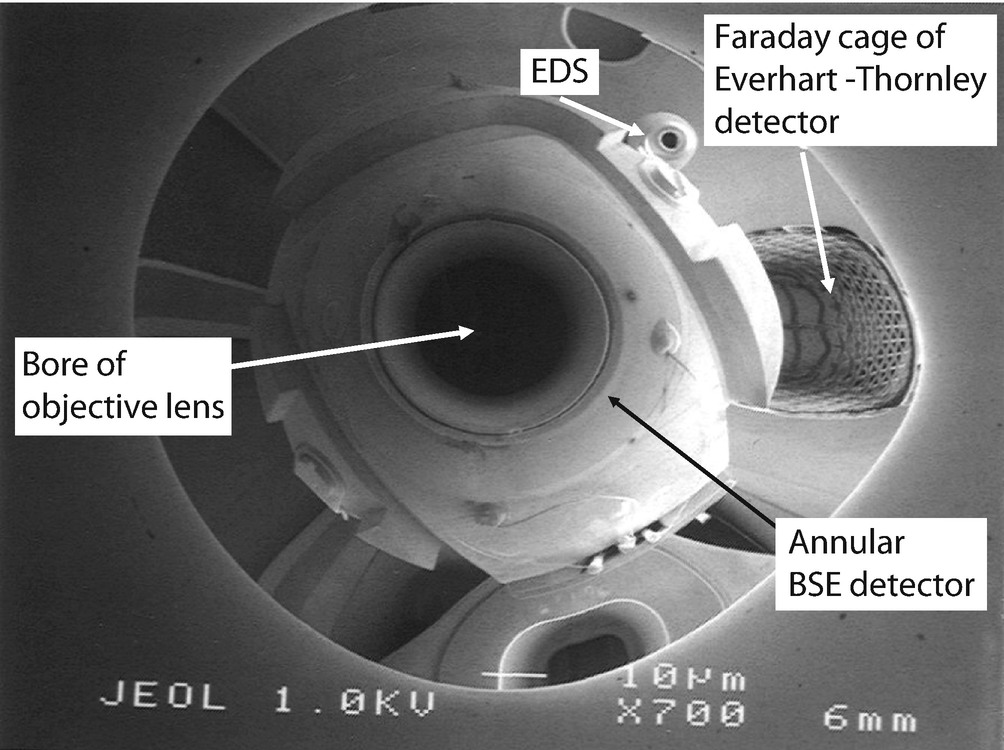

SEM image (Everhart–Thornley detector, positive bias) obtained by disconnecting grounding wire from the specimen stage and reflecting the scan from a flat, conducting substrate; E 0 = 1 keV

If the electrical path to ground is established, then the excess charges will be dissipated in the form of the specimen current provided the specimen has sufficient conductivity. Because all materials (except superconductors) have the property of electrical resistivity, ρ, the specimen has a resistance R (R = ρ L/A, where L is the length of the specimen and A is the cross section), and the passage of the specimen current, i SC, through this resistance will cause a potential drop across the specimen, V = i SC R. For a metal, ρ is typically of the order of 10−6 Ω-cm, so that a specimen 1-cm thick with a cross-sectional area of 1 cm2 will have a resistance of 10−6 Ω, and a beam current of 1 nA (10−9 A) will cause a potential of about 10−15 V to develop across the specimen. For a high purity (undoped) semiconductor such as silicon or germanium, ρ is approximately 104 to 106 Ω-cm, and the 1-nA beam will cause a potential of 1 mV (10−3 V) or less to develop across the 1-cm cube specimen, which is still negligible. The flow of the specimen current to ground becomes a critical problem when dealing with non-conducting (insulating) specimens. Insulating specimens include a very wide variety of materials such as plastics, polymers, elastomers, minerals, rocks, glasses, ceramics, and others, which may be encountered as bulk solids, porous solids, foams, particles, or fibers. Virtually all biological specimens become non-conducting when water is removed by drying, substitution with low vapor pressure polymers, or frozen in place. For an insulator such as an oxide, ρ is very high, 106 to 1016 Ω-cm, which prevents the smooth motion of the electrons injected by the beam through the specimen to ground; electrons accumulate in the immediate vicinity of the beam impact, raising the local potential and creating a range of phenomena described as “charging.”

9.1.2 Recognizing Charging Phenomena in SEM Images

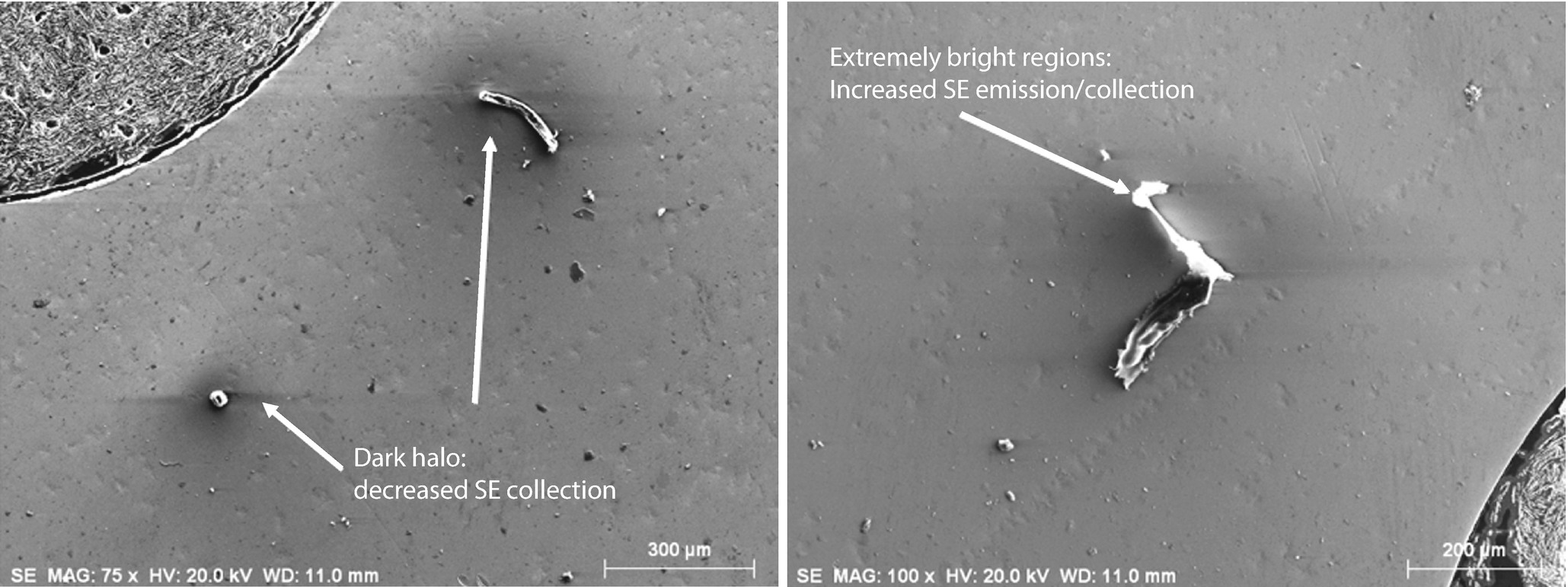

Examples of charging artifacts observed in images of dust particles on a metallic substrate. E 0 = 20 keV; Everhart–Thornley (positive bias) detector

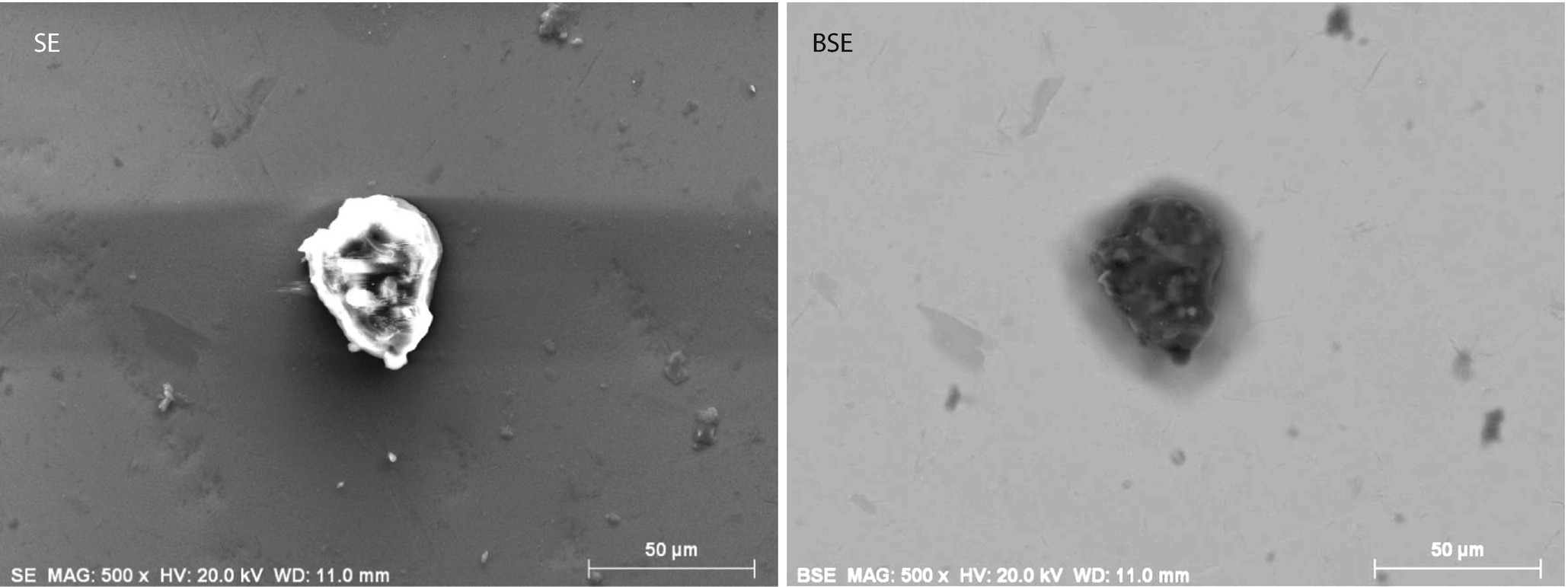

Comparison of images of a dust particle on a metallic substrate: (left) Everhart–Thornley (positive bias) detector; (right) semiconductor BSE (sum) detector; E 0 = 20 keV

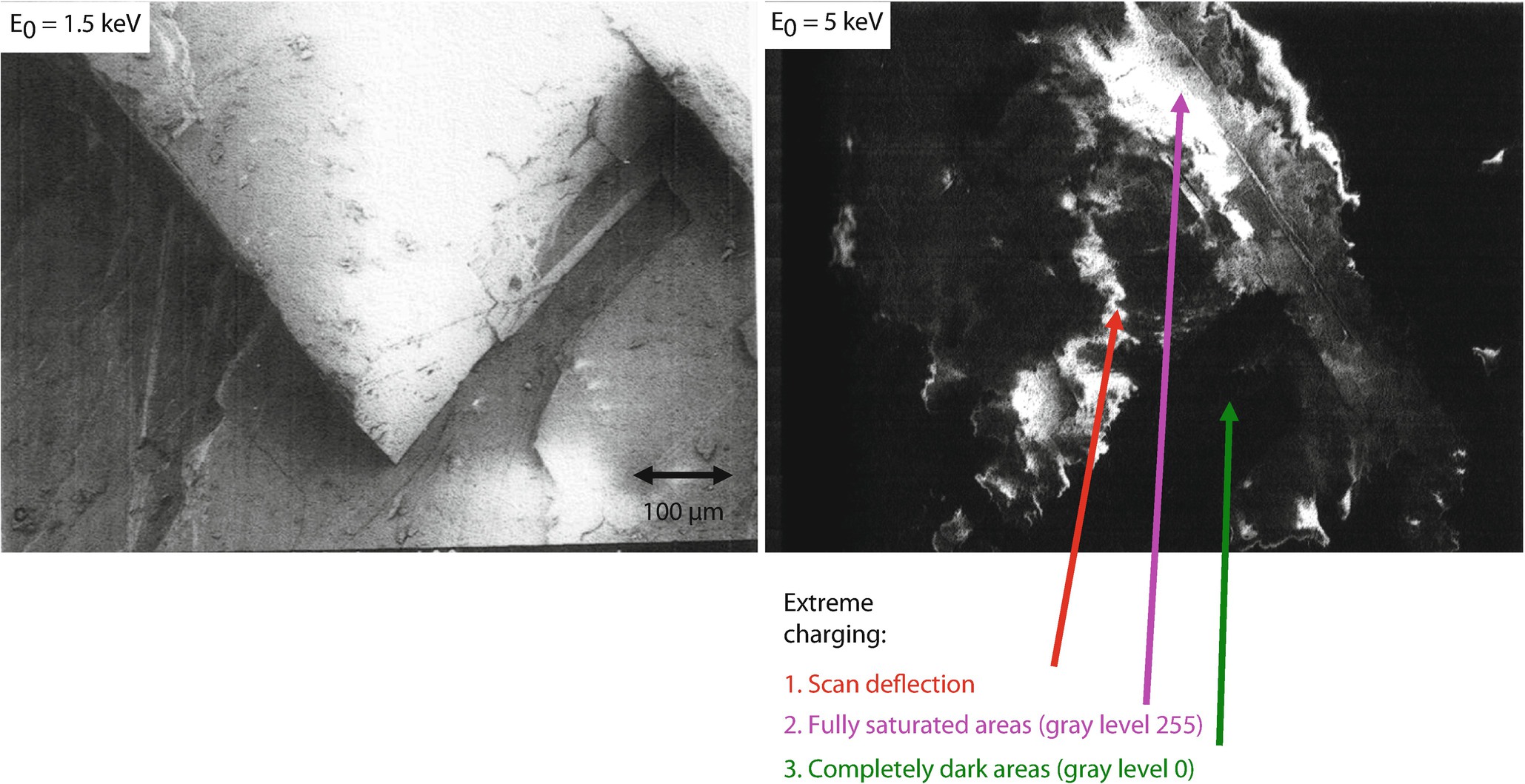

Comparison of images of an uncoated calcite crystal viewed at (left) E 0 = 1.5 keV, showing topographic contrast; (right) E 0 = 5 keV, showing extreme charging effects; Everhart–Thornley (positive bias) detector

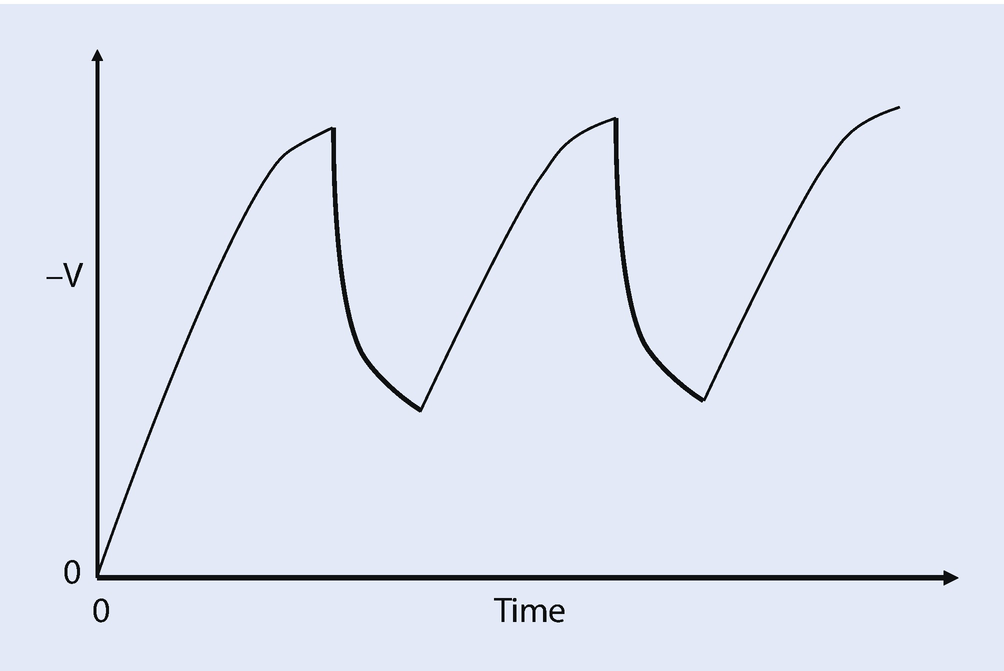

Schematic illustration of the potential developed at a pixel as a function of time showing repeated beam dwells

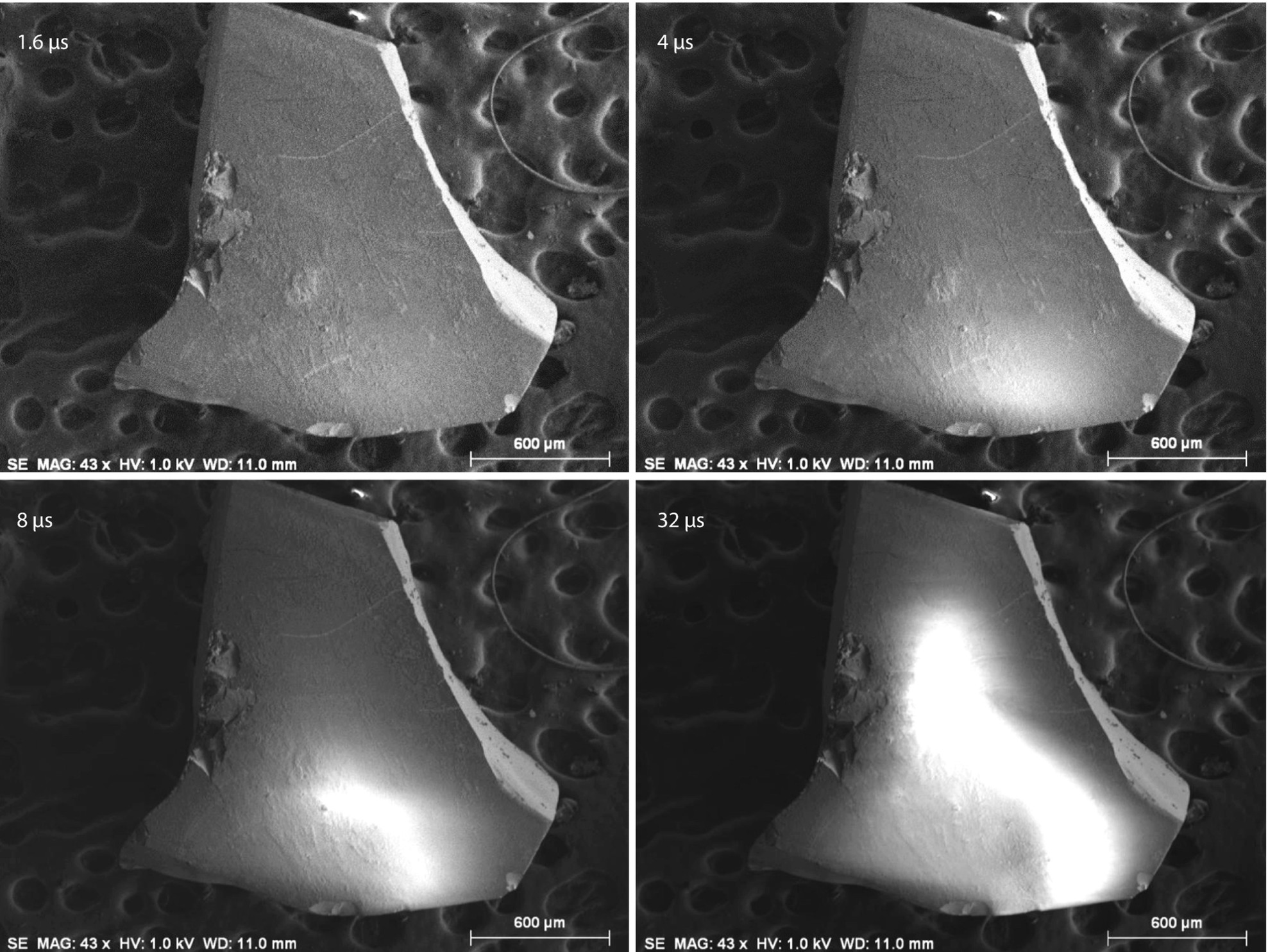

Sequence of images of an uncoated quartz fragment imaged at E 0 = 1 keV with increasing pixel dwell times, showing development of charging; Everhart–Thornley (positive bias) detector

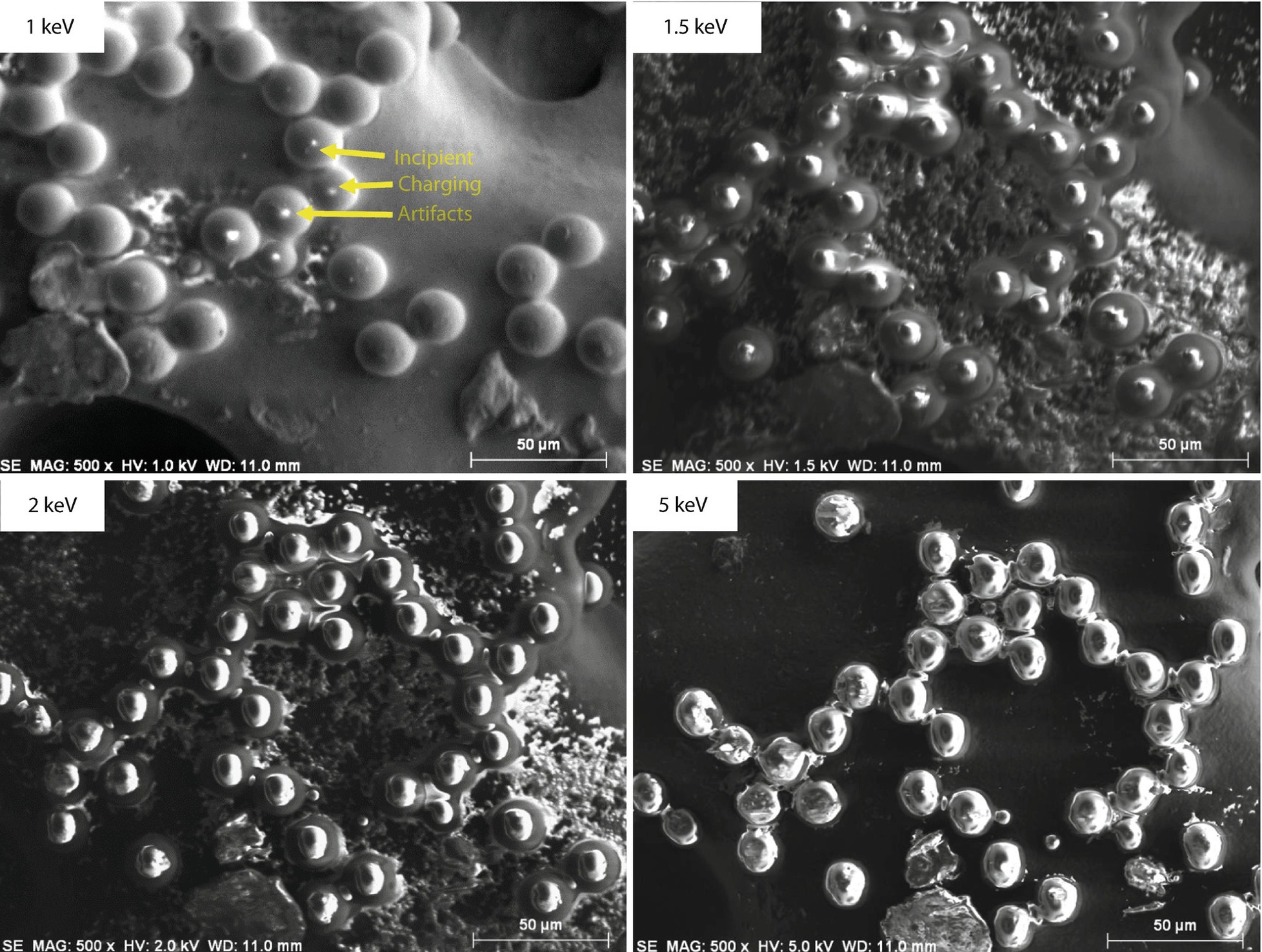

Polystyrene latex spheres imaged over a range of beam energy, showing development of charging artifacts; Everhart–Thornley (positive bias) detector

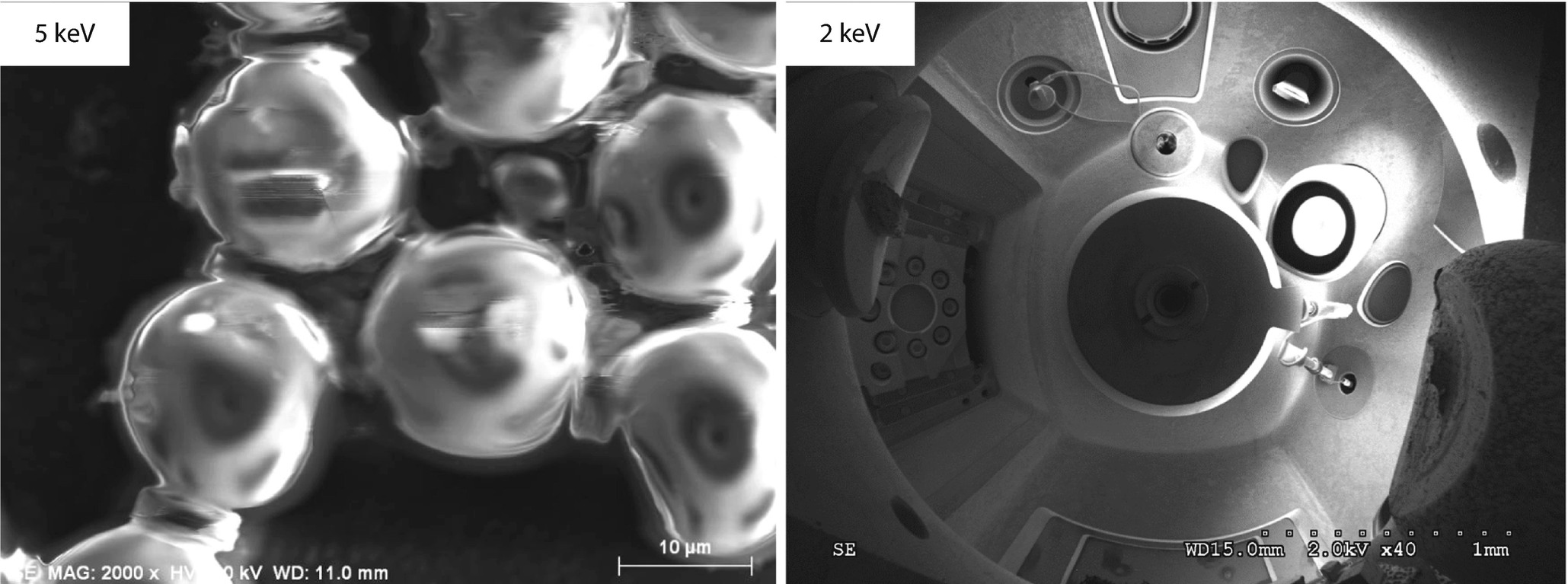

(left) Higher magnification image of PSLs at E 0 = 5 keV; (right) reflection image from large plastic sphere that was charged at E 0 = 10 keV and then imaged at E 0 = 2 keV; Everhart–Thornley (positive bias) detector

9.1.3 Techniques to Control Charging Artifacts (High Vacuum Instruments)

9.1.3.1 Observing Uncoated Specimens

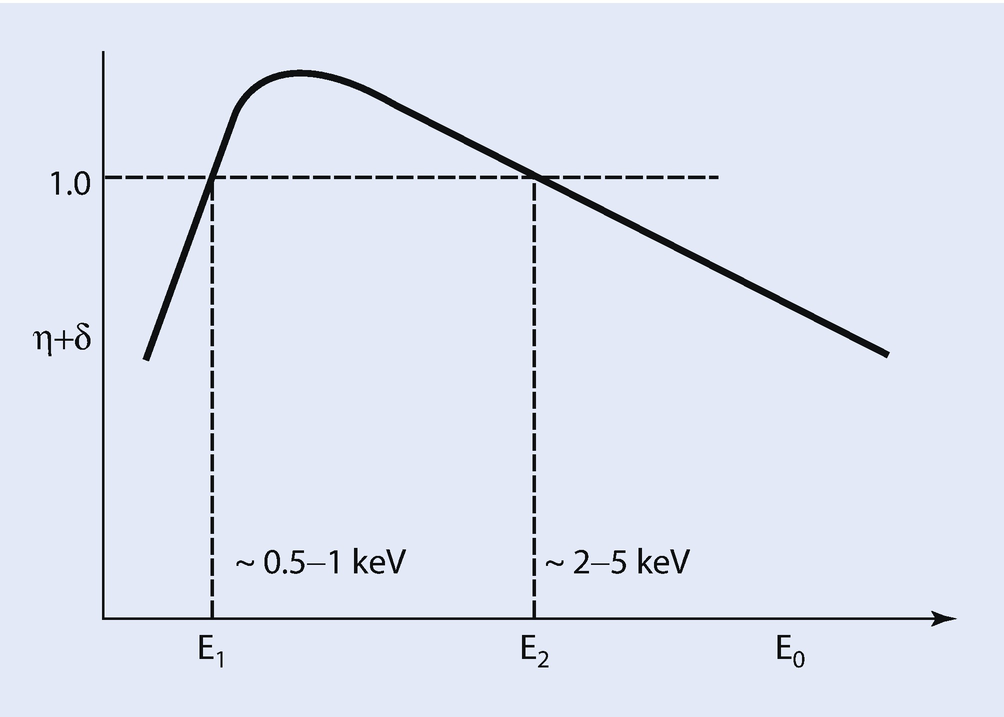

Schematic illustration of the total emission of backscattered electrons and secondary electrons as a function of incident beam energy; note upper and lower cross-over energies where η + δ = 1

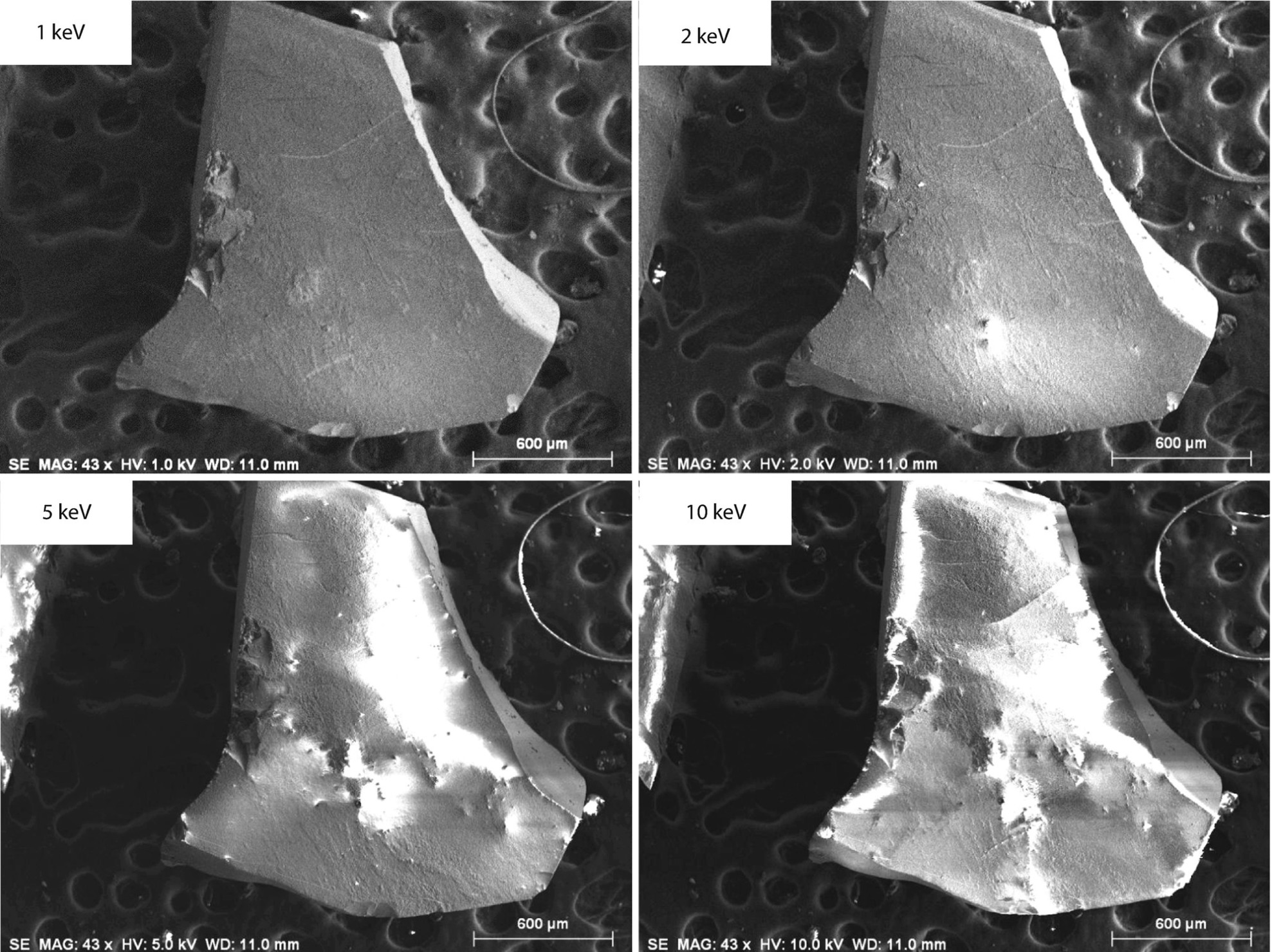

Beam energy sequence showing development of charging as the energy is increased. Specimen: uncoated quartz fragment; 1.6 μs per pixel dwell time; Everhart–Thornley (positive bias) detector

9.1.3.2 Coating an Insulating Specimen for Charge Dissipation

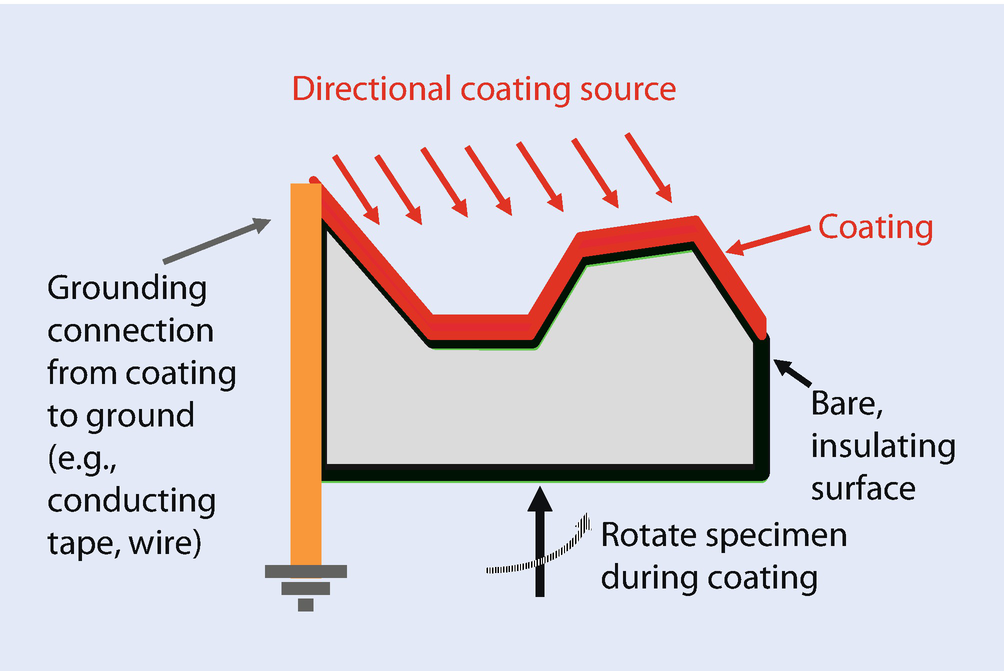

Schematic diagram showing the need to provide a grounding path from a surface coating due to uncoated or poorly coated sides of a non-conducting specimen

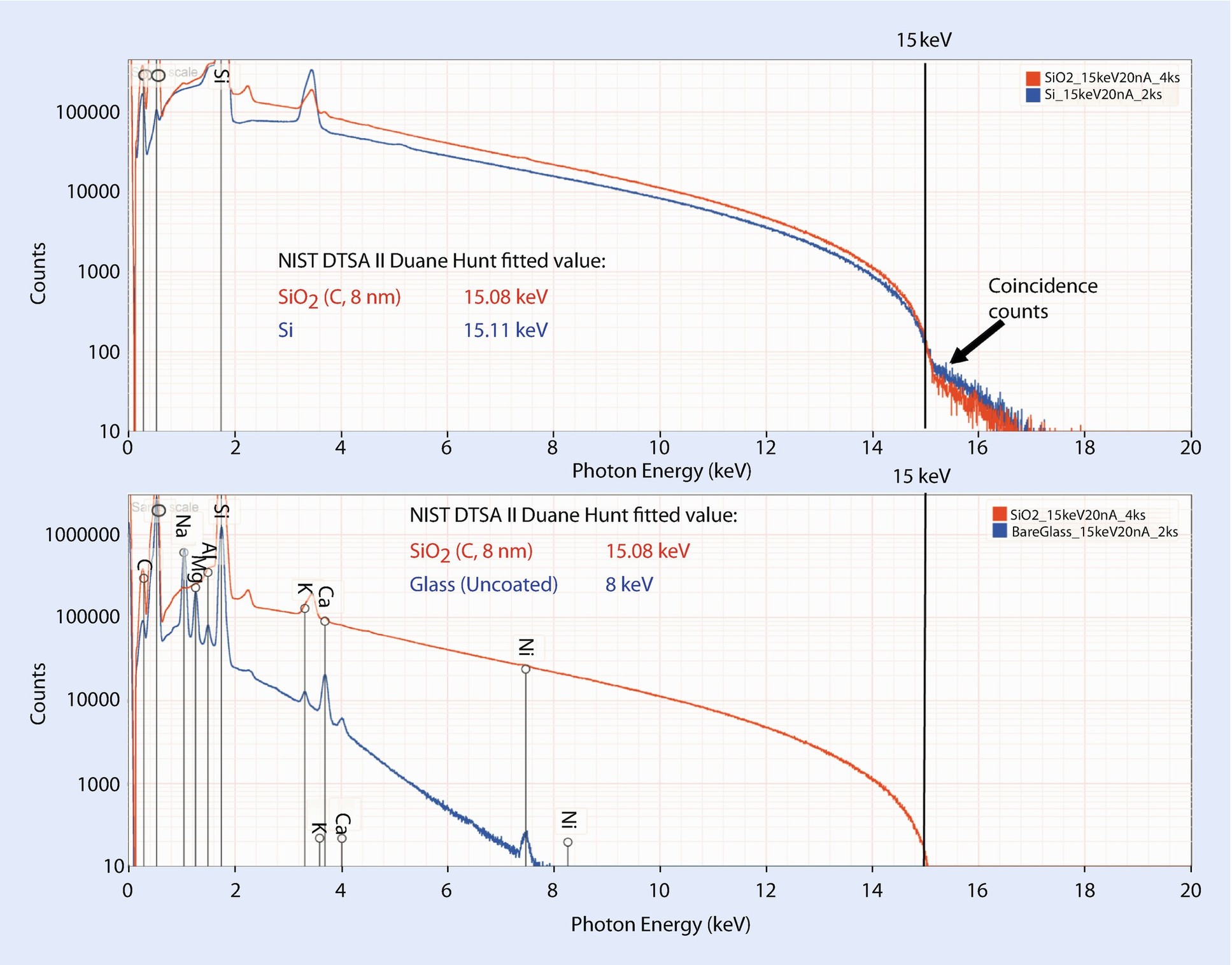

Effects of charging on the Duane–Hunt energy limit of the X-ray continuum: (upper) comparison of silicon and coated (C, 8 nm) SiO2 showing almost identical values; (lower) comparison of coated (C, 8 nm) SiO2 and uncoated glass showing significant depression of the Duane–Hunt limit due to charging

Choosing the Coating for Imaging Morphology

The ideal coating should be continuous and featureless so that it does not interfere with imaging the true fine-scale features of the specimen. Since the SE1 signal is such an important source of high resolution information, a material that has a high SE coefficient should be chosen. Because the SE1 signal originates within a thin surface layer that is a few nanometers in thickness, having this layer consist of a high atomic number material such as gold that has a high SE coefficient will increase the relative abundance of the high resolution SE1 signal, especially if the specimen consists of much lower atomic number materials, such as biological material. By using the thinnest possible coating, there is only a vanishingly small contribution to electron backscattering which would tend to degrade high resolution performance.

Although gold has a high SE coefficient, pure gold tends to form discontinuous islands whose structure can interfere with visualizing the desired specimen fine scale topographic structure. This island formation can be avoided by using alloys such as gold-palladium, or other pure metals, for example, chromium, platinum, or iridium, which can be deposited by plasma ion sputtering or ion beam sputtering. The elevated pressure in the plasma coater tends to randomize the paths followed by the sputtered atoms, reducing the directionality of the deposition and coating many re-entrant surfaces. For specimens which are thermally fragile, low deposition rates combined with specimen cooling can reduce the damage.

9.2 Radiation Damage

Certain materials are susceptible to radiation damage (“beam damage”) under energetic electron bombardment. “Soft” materials such as organic compounds are especially vulnerable to radiation damage, but damage can also be observed in “hard” materials such as minerals and ceramics, especially if water is present in the crystal structure, as is the case for hydrated minerals. Radiation damage can occur at all length scales, from macroscopic to nanoscale. Radiation damage may manifest itself as material decomposition in which mass is actually lost as a volatile gas, or the material may change density, either collapsing or swelling. On an atomic scale, atoms may be dislodged creating vacancies or interstitial atoms in the host lattice.

SEM Everhart–Thornley (positive bias) image of double-sticky conducting tab

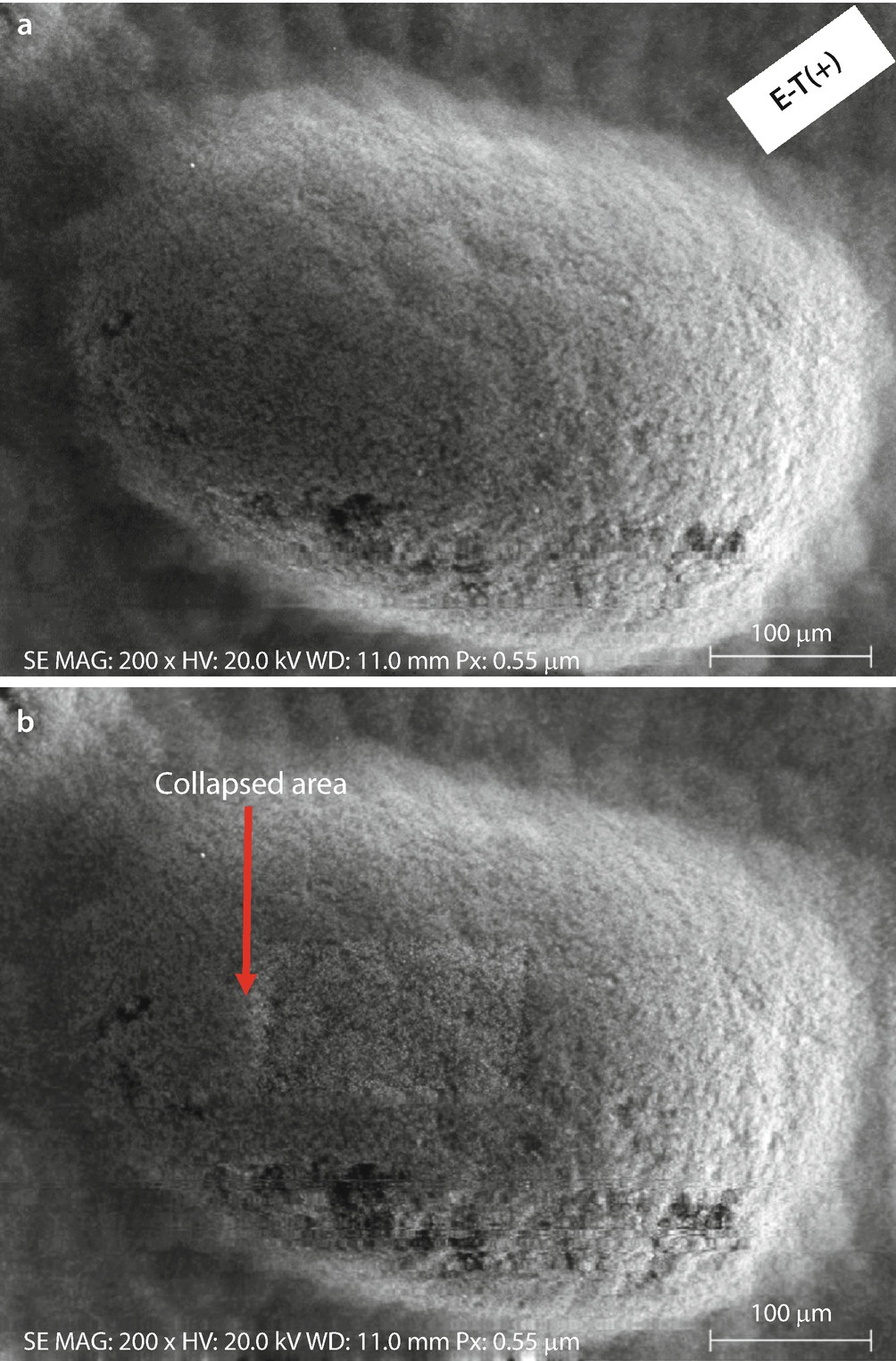

Conducting tape: a Initial image. b Image after a dose of 15 min exposure at higher magnification (20 keV and 10 nA); Everhart–Thornley (positive bias)

- 1.Follow a minimum dose microscopy strategy.

- a.

Radiation damage scales with dose. Use the lowest possible beam current and frame time consistent with establishing the visibility of the features of interest. It may be necessary to determine these parameters for establishing visibility for the particular specimen by operating initially on a portion of the specimen that can be sacrificed.

- b.

Once optimum beam current and frame time have been established, the SEM can be focused and stigmated on an area adjacent to the features of interest, and the stage then translated to bring the area of interest into position. After the image is recorded using the shortest possible frame time consistent with establishing visibility, the beam should be blanked (ideally into a Faraday cup) to stop further electron bombardment while the stored image is examined before proceeding.

- a.

- 2.

Change the beam energy

Intuitively, it would seem logical to lower the beam energy to reduce radiation damage, and depending on the particular material and the exact mechanism of radiation damage, a lower beam energy may be useful. However, the energy deposited per unit volume actually increases significantly as the beam energy is lowered! From the Kanaya–Okayama range, the beam linear beam penetration scales approximately as E 0 1.67 so that the volume excited by the beam scales as (R K-O)3 or E 0 5. The energy deposited per unit volume scales as E 0/E 0 5 or 1/E 0 4. Thus, the volume density of energy deposition increases by a factor of 104 as the beam energy decreases from E 0 = 10 keV to E 0 = 1 keV. Raising the beam energy may actually be a better choice to minimize radiation damage.

- 3.

Lower the specimen temperature

Radiation damage mechanisms may be thermally sensitive. If a cold stage capable of achieving liquid nitrogen temperature or lower is available, radiation damage may be suppressed, especially if low temperature operation is combined with a minimum dose microscopy strategy.

9.3 Contamination

“Contamination” broadly refers to a class of phenomena observed in SEM images in which a foreign material is deposited on the specimen as a result of the electron beam bombardment. Contamination is a manifestation of radiation damage in which the material that undergoes radiation damage is unintentionally present, usually as a result of the original environment of the specimen or as a result of inadequate cleaning during preparation. Contamination typically arises from hydrocarbons that have been previously deposited on the specimen surface, usually inadvertently. Such compounds are very vulnerable to radiation damage. Hydrocarbons may “crack” under electron irradiation into gaseous components, leaving behind a deposit of elemental carbon. While the beam can interact with hydrocarbons present in the area being scanned, electron beam induced migration of hydrocarbons across the surface to actually increase the local contamination has been observed (Hren 1986). Sources of contamination can occur in the SEM itself. However, for a modern SEM that has been well maintained and for which scrupulous attention has been paid to degreasing and subsequently cleanly handling all specimens and stage components, contamination from the instrument itself should be negligible. Ideally, an instrument should be equipped with a vacuum airlock to minimize the exposure of the specimen chamber to laboratory air and possible contamination during sample exchange. A plasma cleaner that operates in the specimen airlock during the pump down cycle can greatly reduce specimen-related contamination by decomposing the hydrocarbons, provided the specimen itself is not damaged by the active oxygen plasma that is produced.

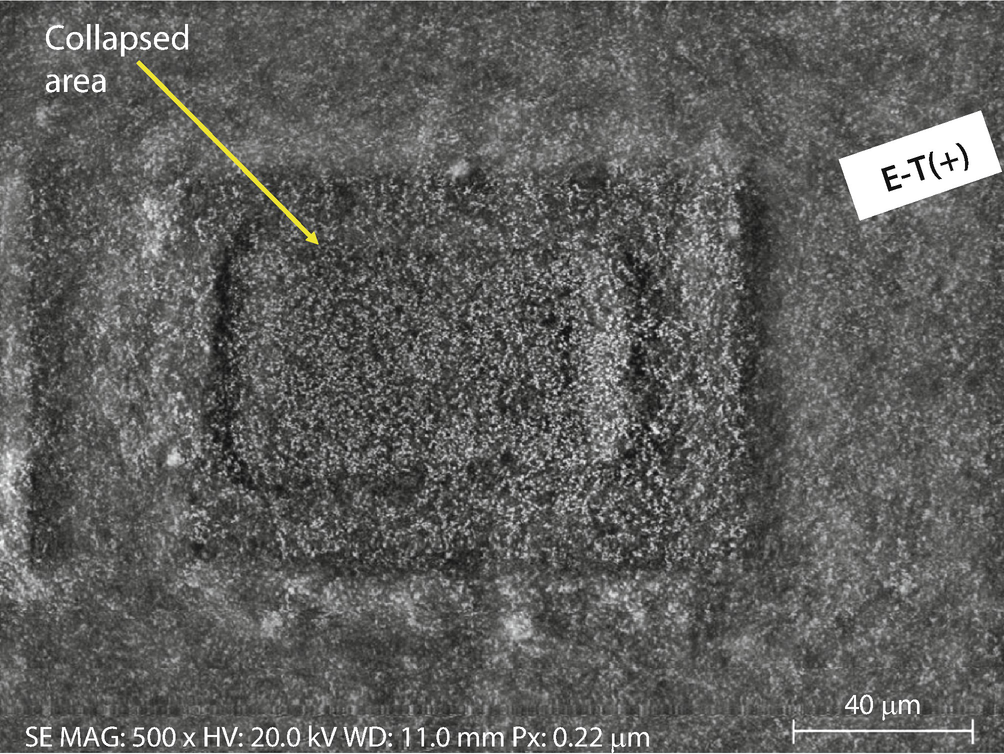

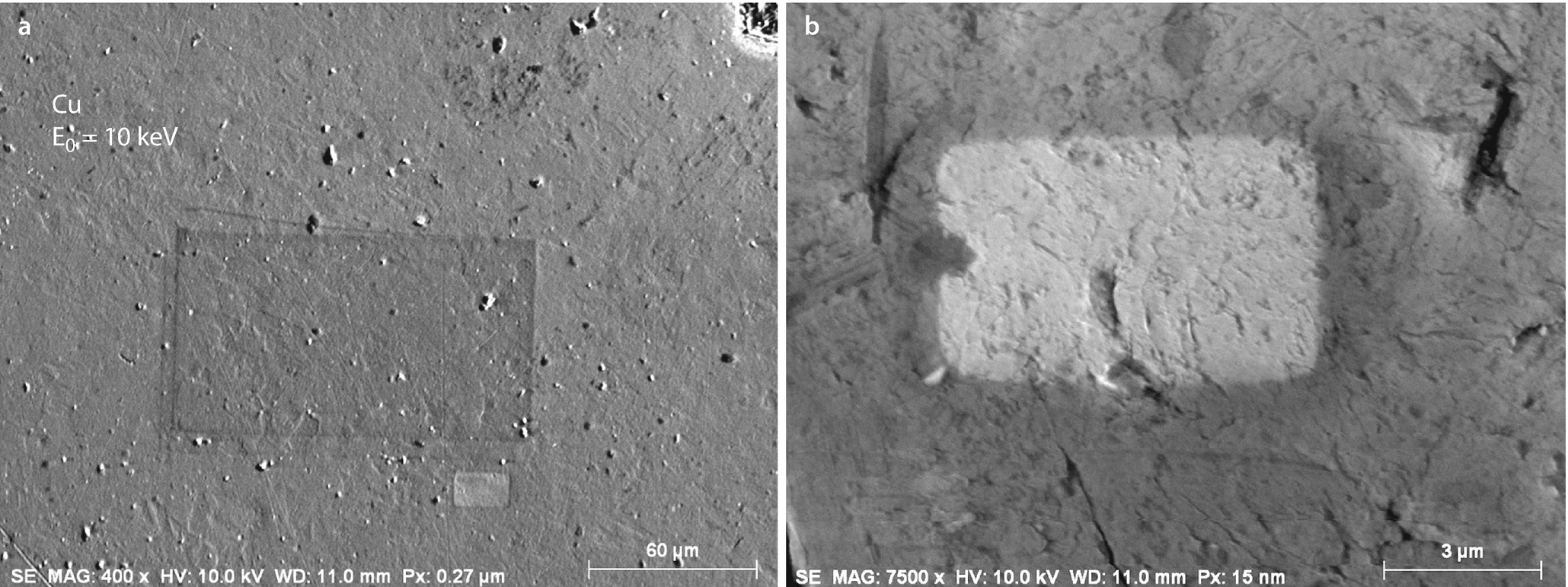

a Contamination area observed after a higher magnification scan; Everhart–Thornley (positive bias). The extent of the contamination is visible upon lowering the magnification of the scan, thus increasing the scanned area. b Etching of a surface contamination layer observed during imaging of an aluminum stub; Everhart–Thornley (positive bias); 10 keV and 10 nA

“Etching,” the opposite of contamination, can also occur (Hren 1986). An example is shown in ◘ Fig. 9.15b, where a bright scan rectangle is observed in an image of an aluminum stub after reducing the magnification following scanning for several minutes at higher magnification. In this case, the radiation damage has actually removed an overlayer of contamination on the specimen, revealing the underlying aluminum with its native oxide surface layer (~4 nm thick), which has an increased SE coefficient compared to the carbon-rich contamination layer.

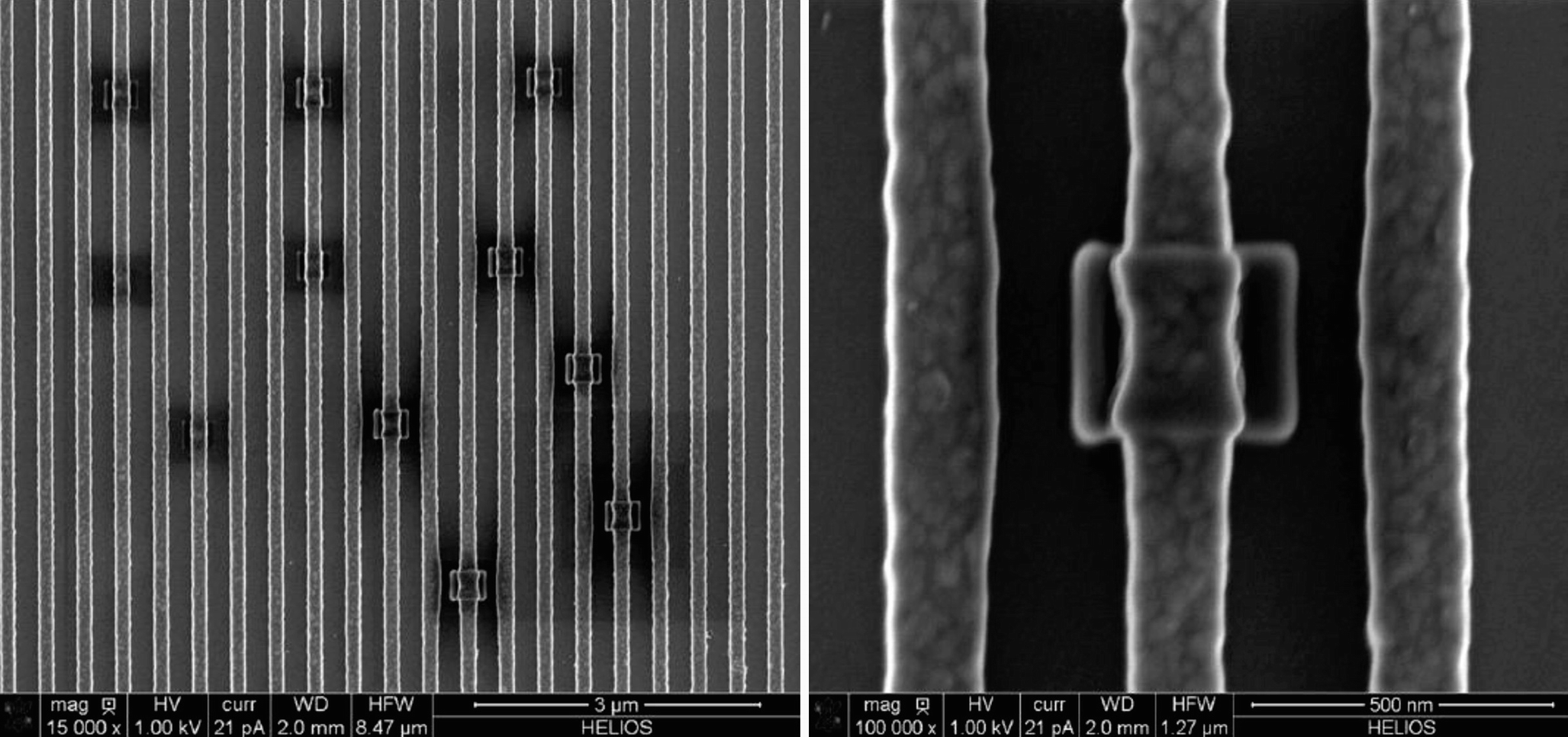

Contamination observed during dimensional measurements performed under high resolution conditions on a patterned silicon substrate (Postek and Vladar 2014). Note broadening of the structure (right) due to contamination

9.4 Moiré Effects: Imaging What Isn’t Actually There

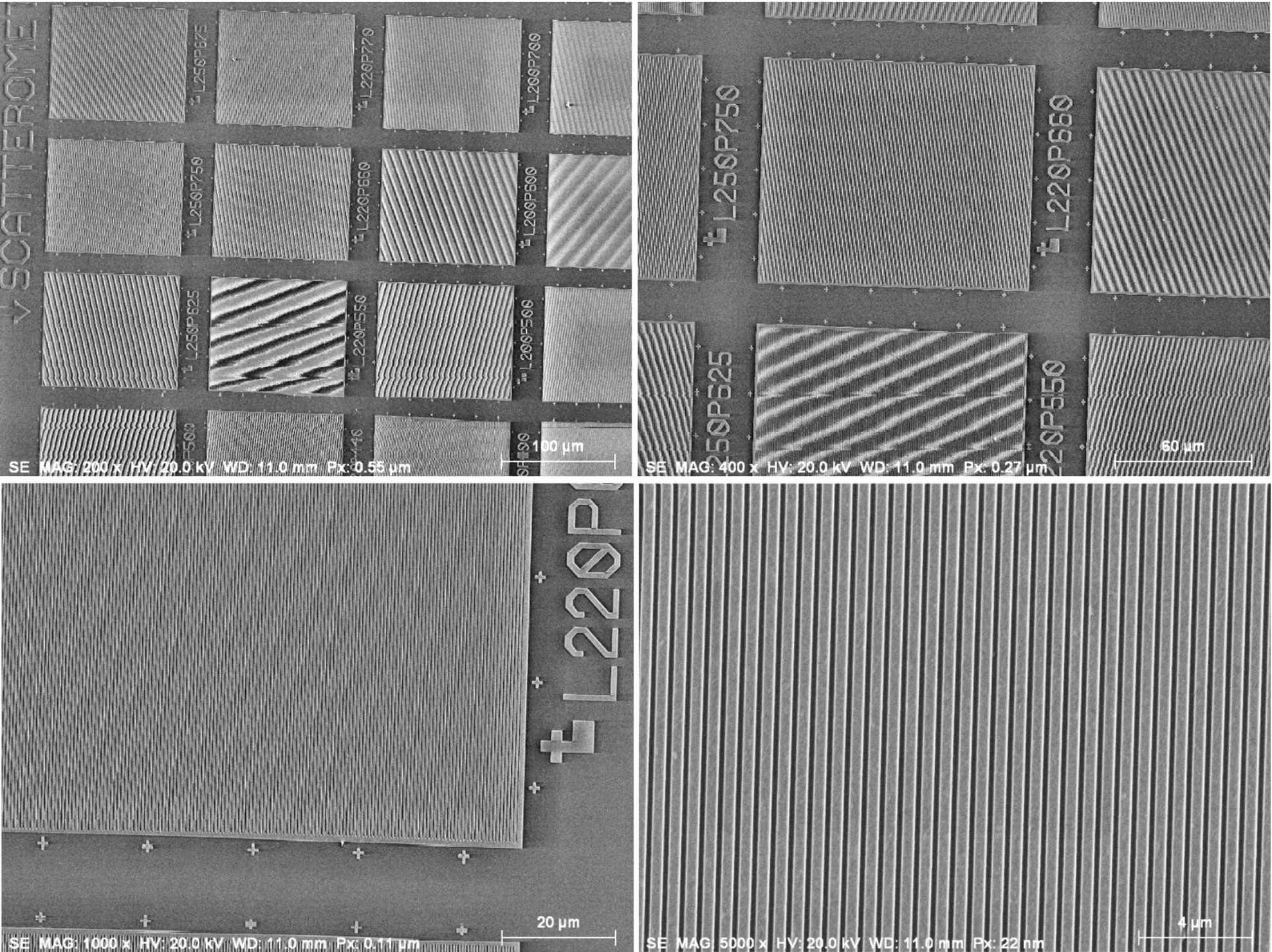

Moiré fringe effects observed for the periodic structures in NIST RM 8820 (magnification calibration artifact). Note the different moiré patterns in the different calibration regions; Everhart–Thornley (positive bias) detector

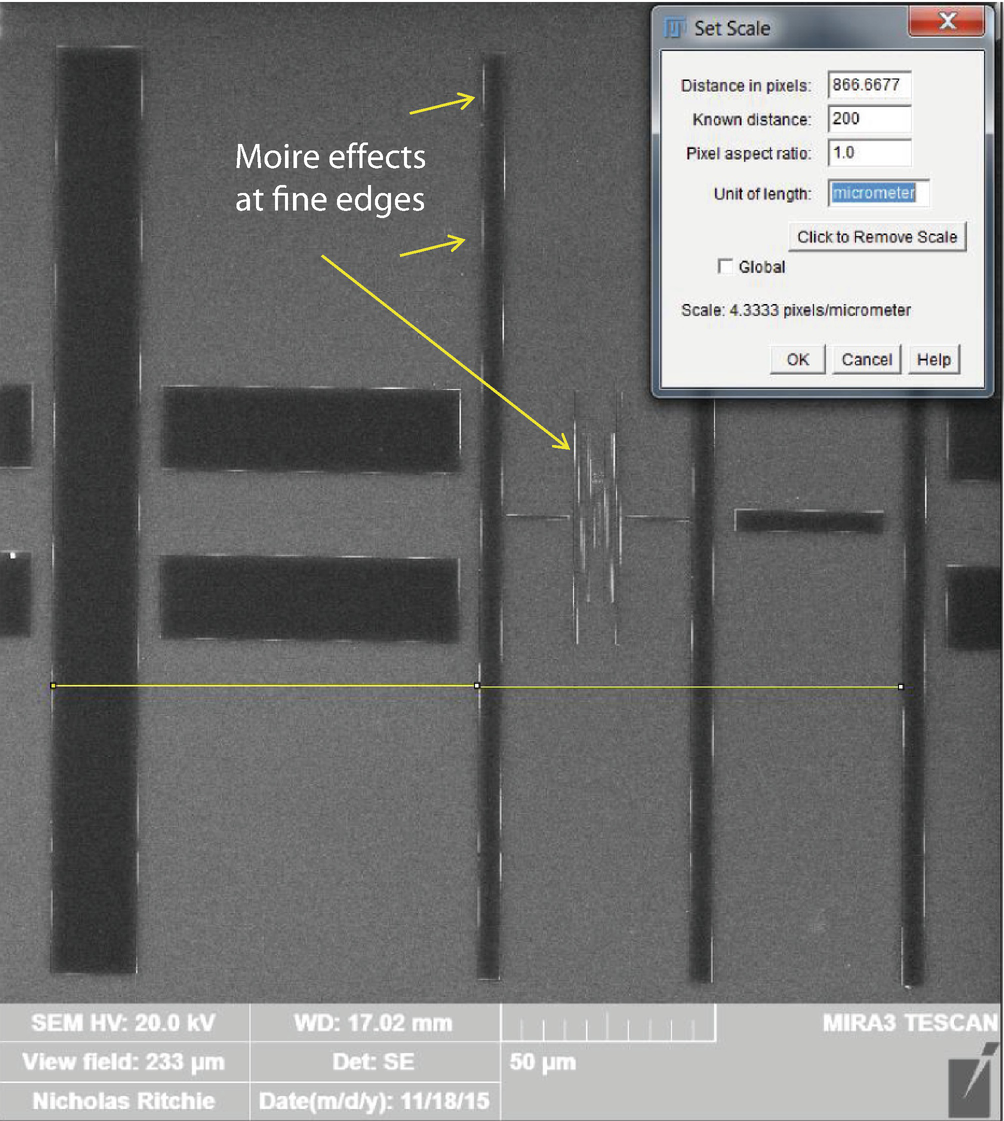

Moiré effects seen as periodic bright flares at the edge of fine structures in NIST RM 8820 (magnification calibration artifact); Everhart–Thornley (positive bias) detector

To avoid interpreting moiré effects as real structures, the relative position and/or rotation of the specimen and the scan grid should be changed. A real structure will be preserved by such an action, while the moiré pattern will change.

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.