The Other Athames

While most athame blades are made of stainless steel or some other type of metal, an athame can be made of most any material that can be sharpened to a point. The most popular materials outside of metal are generally stone, wood, and bone. I’ve seen a few athames with plastic blades as well, but unless it’s a blade for a young Witchling, it’s not something I (and most other Witches) recommend.

As long as you aren’t part of a Witch tradition that mandates a certain type of blade during ritual, the materials that can be used to make your athame are nearly limitless. What’s most important is that the athame works for (and with) you. If you feel a connection to stone instead of steel, by all means go in that direction. Other than the rule of “an it harm none, do what you will,” Witchcraft isn’t about do’s and don’ts; it’s about what works for the individual Witch!

Stone Athames

Human beings have used stone knives for tens of thousands of years. Because of their great antiquity, it’s not surprising that many Witches employ an athame made of rock. When I use an athame made of stone, I often feel a deep connection to truly ancient pagan practices. Before all of the great civilizations in history, there were ingenious people using stone knives and tools. When I use an athame made of that material, it’s a way of honoring those ancestors.

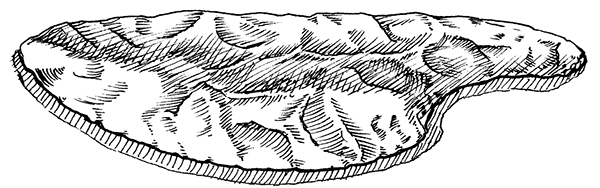

Stone knives are made through a process known as “knapping,” which mostly involves hitting a soft piece of stone with a heavier one. If it sounds labor-intensive, that’s because it is! However, it also doesn’t require a whole lot of tools or materials. Knapping was one of the first technologies used by human beings and is still being used in many places today.

I’ve encountered many naturally occurring rocks over the years that are nearly knife-shaped. Such natural athames make for great impromptu tools when doing rituals in the great outdoors. Stone athames (along with wooden ones) also make great alternatives to the traditional steel athame when doing ritual in a public place. If you are doing ritual in a public park, metal knives might not be allowed, but a dull stone knife is usually fine.

An athame of stone has different characteristics than one made of steel. I generally associate stone athames with the element of earth (since that’s where they come from), but that can vary depending on the stone being used for the athame. A material such as obsidian, for example, which comes directly from active volcanoes, still has a lot of fire associations.

The more masculine energy generally characteristic of the athame remains in place with most stone blades, but that energy is often tempered with an extra layer of protection. Many of the stones commonly used for athames have a very protective energy, and this is often felt in the energy of a circle cast with a stone blade. For a coven or individual interested in a less masculine athame, a stone such as jade might be a good choice.

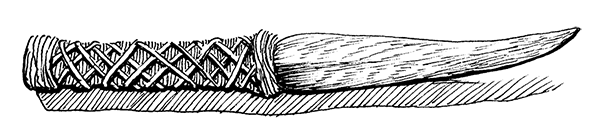

Flint knife

Flint knife

Any type of stone can be used to make an athame, but some are more popular than others. Nearly all the stones listed here are commonly used in athames and can be purchased online and at many New Age/metaphysical shops.

Obsidian: Obsidian is a natural form of black glass and is a popular choice for those who prefer an athame made of stone. Traditionally, obsidian has been associated with protection, but it also makes a great tool for scrying. Most people scry into mirrors, but if you have an obsidian athame, there’s no reason you can’t use your blade for the practice. Obsidian knives have been popular for centuries and can still be purchased easily today.

Hematite: Few stones contain more power and energy then hematite, and it’s become a popular choice for athames over the last decade. It’s a great stone for healing, and an athame made of it can help draw sickness from the body. A hematite athame can be used to help stabilize and balance the energies of a circle. Due to its high iron content, hematite also has strong protective properties.

Quartz Crystal: Quartz is one of the most popular gemstones in modern magick and is increasingly being used for athame blades. Quartz is well known for its ability to amplify magical energy, and its use as a blade naturally complements the athame’s primary purpose. Many Witches take advantage of crystal’s natural abilities by adding it to the hilts of their athames. I’ve even heard of a few Witches attaching a piece of crystal to the blade of their knives while casting a circle for a little extra added oomph. Quartz crystal has been used in religious ceremonies all around the world. It’s one of humanity’s original mystical and magical stones.

Flint: Flint is a great choice for a stone athame in North America because of its extensive use by Native Americans. Flint was used by Native American shamans for ceremonial purposes and by hunters who used it in spear and arrow points. In both Europe and the Americas, flint was also used to make knives. Flint has long been associated with protection, and when used in an athame, that energy will show up in your circle casting. Flint also has a long history as an aid to starting fires, further connecting the athame to the element of fire.

Chert: Chert (often called common chert) is nearly the same chemically as flint but is thought by many to be less “pretty.” Like its more popular cousin, chert was one of the first stones used to make knives and is also easy to work with. Many forms of chert contain fossils within them, adding a little extra energy to any athame made of this stone.

Marble: Marble is probably best known as the primary building material of the Romans and the Greeks, but it’s been used throughout the world for centuries. Marble is a popular building material because it’s easily worked with and durable, two useful qualities for those interested in constructing their own stone athame. Because of its associations with the Greeks, marble is a good choice for the Witch who has an interest in (or relationship with) Hellenic deities.

Petrified Wood: Petrified wood isn’t a stone, but it’s not quite wood anymore either, so this seemed like the place to include it. What’s fascinating about petrified wood is that it’s a substance that lives in two worlds. It feels like a stone and yet has the story and energy of something that was once alive. Because of its connection to a living past, an athame made of petrified wood can be used to explore past lives and is a good energy to utilize in rituals (like Samhain) that deal with the dead.

Athames of Wood

Wood is most commonly used in the construction of wands, but it’s also a material that makes a great athame. One of my oldest friends in the Craft has exclusively used a wooden athame for over twenty years very effectively. Unlike athames of stone and steel, every bit of a wooden athame has been “alive” at some point in the recent past. That gives wooden athames a very unique energy signature.

What element a wooden athame is representative of really depends on the individual Witch. It’s easy to associate a wooden blade with earth; the roots of a tree do grow deeply into the womb of the Great Mother. The traditional association with fire also works as well, but I usually associate wooden athames with the element of air. Most wooden blades are made from branches and not tree trunks. Those branches often “reach up” into the sky and are generally shaken and stirred by a strong breeze.

Wooden knife

Wooden knife

There are a couple of practical reasons for working with a wooden athame in certain situations. Air is generally a very welcoming element, and casting a circle with a force associated with that element creates a less protective and more inviting circle. (I like to think of it as the “screen door” of ritual circles.) Many Witches work with the fey (sometimes called fairies and generally a reference to many different supernatural beings that many consider mythological), a people who traditionally don’t like iron and steel. Using a steel athame when calling to the fey might result in them ignoring your invitation.

If you choose to work with a wooden athame, it’s best to use a knife created from a fallen tree branch. If that’s not possible, be sure to “ask” the tree before removing a branch from it. Trees don’t usually “speak,” but they will often send a pretty clear signal via energy. If the tree you are pinching from gives you the go-ahead to cut down a branch, be sure to thank it when you are done. It’s traditional to leave coins, but I think it makes more sense to leave the tree in question a big drink of water for its roots. It’s not just good karma; it makes for good magick.

Wood also provides a powerful way to connect with the local environment. It’s much easier to know the “point of origin” with wood than it is with steel or even stone. If your practice is rooted in a deep sense of place, athames made of wood are a good choice.

Because trees have very specific energies and associations, an athame made from one will contain a few “extra properties.” If you are looking to undertake a very specific working, a circle cast with a wooden athame might be helpful. Listed here are a few magical woods (which may or may not be common, depending on where you live) that might come in handy during ritual.

Apple: An athame of apple wood adds a little extra magick when performing a love spell. Apples have long been associated with the immortality of the soul and are effective for when an athame is being used to create a portal into the Summerlands.

Ash: In some Nordic traditions, Yggdrasil (the World Tree) was as an ash tree, a perfect association for a wood that many see as a useful tool for traveling between the worlds. Due to this property, ash is an exceptional wood for an athame.

Boxthorn: The “thorn” in the poem “Oak and Ash and Thorn,” boxthorn has long been prized for its properties of healing and virility.

Elder: An athame made of elder provides a bit of extra energy when warding off a magical attack or dealing with negative spirits. Ghost hunters would be wise to carry an extra athame made of elder just in case.

Hazel: Hazel has long been used for dowsing rods and is a good choice if you plan to use your athame for divination. It’s also traditionally associated with fertility and can give added meaning to the symbolic Great Rite.

Oak: Since this tree is sacred to Druids and long associated with health and protection, an athame made from oak is especially useful for those who work with Celtic deities.

Redwood: Redwood is very soft, which makes it easy to carve an athame out of, but hard to carve symbols into. Redwood is extremely resistant to fire and insects and provides a useful energy when trying to overcome long-term problems. Redwoods are some of the oldest trees in the world and a powerful way to tap into the wild powers of nature.

Walnut: The walnut is a symbol of male virility, and its wood has similar energies. Walnut also increases mental focus and powers, and in recent times has come to be associated with things like telepathy. This is a good wood to use when trying to open up lines of communication.

Yew: Yew trees are poisonous, and because of this, some Witches are wary of them. I believe that the yew’s proximity to death makes it an effective wood for Samhain rites and rituals of transition.

Making a Wooden Athame

The number of tools required to make a wooden athame is minimal, and the process from start to finish requires only a few hours. If you choose to make a wooden athame, you’ll want to start by rounding up a suitable piece of wood. I suggest using a fallen tree branch instead of a store-bought piece of wood. Whatever you use should feel comfortable in your hand and shouldn’t be any thicker than your wrist. You can make your wooden athame as long or as short as you wish, but most wooden athames I’ve seen over the years have a pretty short blade.

After you find a suitable branch, the most important tool you’ll need is a pocket or bowie knife. A bowie knife is sharper and will speed up the process, but pocket knives are far more common and often easier to acquire. You may also want some sandpaper, some tape or ribbon for the hilt, and some wood sealer, but those last items aren’t completely necessary.

Start by discarding any parts of the stick you don’t need. If your branch is twelve inches long, you’ll probably want to get rid of about half the length. Next you’ll want to trim off all the bark and any imperfections in the wood, especially any knots that stick out. Your goal here is simply to create a smooth and even piece of wood. When you’re done, be sure to mark off an area for your athame’s handle. You can make a notch with the knife you are using or make a small mark with a pencil.

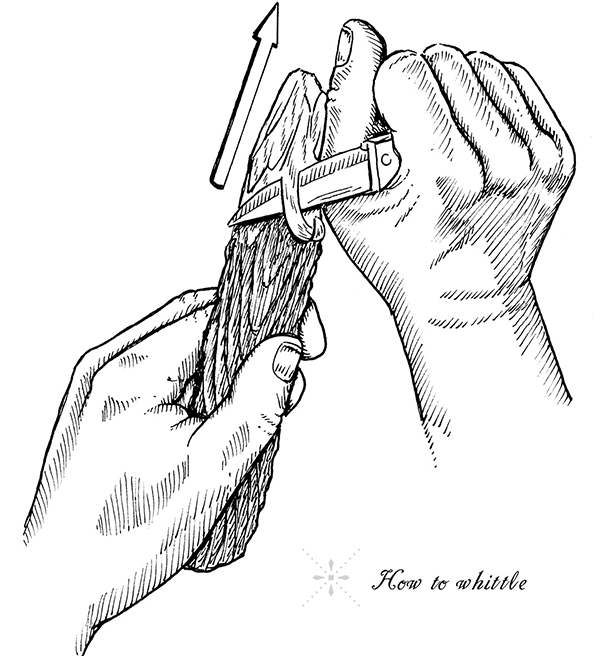

Making an athame out of wood requires a lot of whittling, and it sometimes takes a few hours. It’s a pretty simple stroke with the pocketknife, similar to peeling a potato. The only difference is that the pressure of each knife stroke should increase with each “whittle” down the stick. When you’ve got the basic shape down, keep whittling until the blade looks like you want it to. I’m not all that crafty; when making a wooden athame, I’m just hoping for a blade-like shape with a point at the end! Anytime one cuts with a knife, the blade should be moving away from the body. This isn’t only for safety; it’s the easiest way to use a knife.

When your athame is suitably knife-shaped, you may want to smooth it down a bit with some sandpaper. Sandpaper is especially useful if you want the blade to be completely uniform. Though it’s not necessary, I also suggest adding a wood finish to your blade. This will keep it safe from outside elements and give it a shiny look. Alternatively, you can also polish the blade with beeswax for a similar effect.

The easiest way to make a hilt is simply to take the part of the branch you marked earlier as the handle and cover it with soft cloth ribbon or tape. Coating the hilt with wood glue and then wrapping cloth ribbon around it is the easiest way to create a working handle. If you’ve done a good job sanding the handle area (no one wants a splinter during ritual!), painting or staining a hilt onto the blade is also acceptable. Electrical and duct tape are easy ways out here too, but I’m generally wary of industrial-grade plastics.

Once you’ve got a wrap on the handle, you’ll be all done and will have crafted your very own athame. It may not look all that fancy, but it will work in ritual and in whatever magical workings you undertake. As long as you are happy with it, the gods will be happy with it too!

Blades of Bone and Antler

Bone is more likely to be used for the hilt of an athame, but athame blades made from bone aren’t unheard of and may be gaining in popularity. Bone knives are ancient, and there is some evidence to suggest that they were used in religious ceremonies 15,000 years ago. Ice Age cave dwellers in what is now modern-day France made bone knives decorated with seasonal motifs and never used those knives for hunting.14 Could they be the world’s oldest athames? Probably not, but it seems likely that they were used for some sort of spiritual purpose.

I’ve always found the idea of a bone knife a bit uncomfortable, but I think that’s more a reflection of my own personal prejudices. Bone knives offer yet another way to connect with our ancient ancestors and with any spirit animals we might feel close to. If someone has a spiritual bond with a particular animal, wouldn’t it make sense for them to use a tool made from that animal? I don’t own a bone athame, but I do own a set of deer antlers I wear on occasion, and I find them to be a great way to honor deer and the natural world. Why would a bone blade be any different?

I do think it’s wise to be cautious when first using an athame made of bone. Since that bone (or perhaps antler) came from a once-living creature, that animal’s spirit may still be hovering nearby. I think it’s important to always treat an athame with respect, but perhaps even more so when a piece of that athame came directly from a living creature. I wouldn’t want anyone disrespecting the bones of my deceased relatives; the bones of our brothers and sisters in the animal kingdom shouldn’t be any different.

Most Witches I know who use bone in their athames either find it in the woods or get their materials from hunters they know to be in touch with the natural world. Most bone blades are not mass-produced but come from artisans who try to honor the spirit of the deceased animal whose parts they are working with. Since bone generally comes to us after an animal dies, the energy in a bone blade is going to be different from that of most other athames. That doesn’t make it bad, but only different. If you do end up using a bone athame, proceed with caution until you are used to the energies it emits.

The Secret Athames

In chapter 13 of his 1954 book Witchcraft Today, Gerald Gardner wrote:

It is very amusing to see how clever some witches are in disguising their tools so that they look like something else; indeed, they often are something else, until they are put together in the proper way to be used.

Even today, there are many Witches who must hide and disguise their magical tools for a variety of reasons. Luckily for us, most Witch-tools are easily disguised, and if you find yourself in a situation where using a traditional athame is not possible, you’ve got lots of options.

My wife became a Witch when she was sixteen years old, and it was something she had to keep secret. She attended a Catholic high school and her mother was (and remains) a very conservative Catholic. When my wife began collecting her magical tools, she decided that the traditional double-sided knife was out of the question, so she sought an alternative.

She eventually settled on a letter opener. Like a more traditional athame, it had a double-sided blade and a wooden handle. Even the letter opener’s hilt was black! The only real difference between her letter-opener athame and a more conventional one was the thinness of the blade itself. Her letter-opener athame was so inconspicuous that she could even leave it on the desk in her room without any worry.

When my wife entered college, she ended up living in the dormitory of her university. Weapons were not allowed in her dorm room, so her letter-opener athame came in handy yet again. She used it all throughout college and even beyond because she felt so comfortable with it. Even now, her first athame holds a place of honor on one of our many household altars.

There are other secret athames too. People have been using Swiss Army knives as athames for decades now (it’s even mentioned in 1979’s The Spiral Dance by Starhawk). Most people don’t feel threatened by a “knife” that also contains a corkscrew and a bottle opener. For Witches living in the broom closet, a Swiss Army knife athame is a completely inconspicuous choice for use outdoors. I wish I had thought of it back when I was a Boy Scout!

Kitchen knives also work well if you are in a situation where your interest in Witchcraft has to be kept hidden. A steak knife or even a butter knife smuggled out of the kitchen and kept on a nightstand probably won’t attract much attention. You can also just put it back in the kitchen when you are done. The downside to using a kitchen knife is that your athame will probably end up getting handled by a lot of different people. If that’s acceptable to you, then raid those cupboards!

Toy plastic knives and swords are easy to come by (especially swords), and I’ve known a few people who have used them as athames over the years. I’m not a big fan of mass-produced, industrialized, polluting plastic as a material for athames, but we do what we have to do sometimes. In dim light, a plastic sword sometimes looks as impressive as the real thing. A Witch must always be practical, and if a plastic knife is the best option available, then go with it.

Lupa

i didn’t make my own athame. Because I create art for a living, I’m too close to my work; the energy’s too familiar. Don’t get me wrong: I love what I do and what I create, and I’ve had many people remark on the power in the athames I craft from bone and horn, leather and fur, beads and charms. But when I’m creating a formal ritual, I need to be able to step outside of myself, so I recruit the art of others in my efforts.

The flow of creation is second nature to me at this point, after almost twenty years of making sacred items. I breathe it; I could craft in my sleep. In fact, I’ve dreamed some of my best ideas, or had them come to me in that liminal state between wakefulness and slumber. And the athames are among some of my most elaborate works, physically and energetically. They pull me in more deeply, challenging me as an artist and a spiritual creator, absorbing more of me than most of the pieces that leave my studio for the wider world.

The blade is almost always bone or horn, usually water buffalo. The handles are more varied: wolf bone, elk antler, coyote femur, stag tine. The hilt and handle are wrapped, sometimes in leather and sometimes in fur and sometimes in bright swaths of braided secondhand yarn. The pommel offers even more opportunities for customization, where beads and feathers and other shiny objects can dangle and gleam.

And what is the blade without its sheath? Deerskin is my usual go-to; it can handle the gentler attentions of dull bone and horn where metal might otherwise slash and tear. Here the theme is continued from the knife itself—maybe silver on black, or red and gold, and often the deep earth tones of the forest, with an antler button to finish it all.

The spirits, too, have their say. I work with hides and bones and the animal spirits within them, listening to their requests and demands, and trying my best to give form to these forces I hold in my mortal hands. I never incorporate a bit of fur or antler until it’s ready; every piece of art I make includes the conversation I had with these deceased beings about the care of their remains. I feel the voices thrum in my bones; I hear them in my heart. Every bit of it goes into the knife and sheath, giving them a life not found in mass-produced plastic and steel.

I never know until the end how each athame will look, but I never fail to fall in love. I do know I can’t keep them all. So I send them off to other homes, with a prayer to the spirits who once wore these sacred remains, and a wish for a good new afterlife in a sacred place.

Lupa

Author and Artist •

www.thegreenwolf.com

14. Alexander Marshack, “Exploring the Mind of Ice Age Man,” National Geographic vol. 147, no. 1 (1975), p. 83