The Boline and the

White-Handled Knife

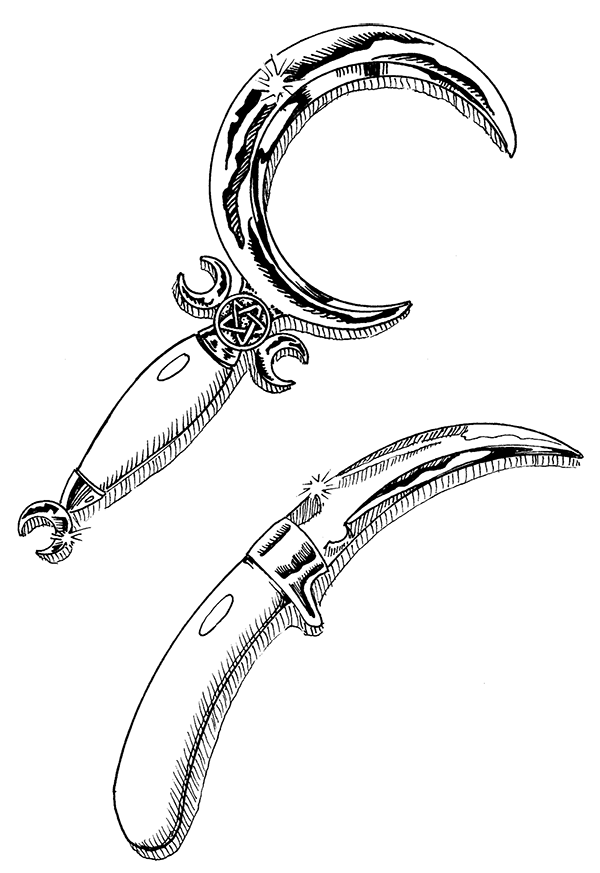

The first modern Witches generally used three different knives in their practices. The first was, of course, the athame, and it was seldom if ever used for any actual physical cutting. For physical cutting, most Witches used the unimaginatively titled white-handled knife, sometimes called a kerfan (or kirfane). A third sickle-shaped or slightly curved knife called a boline, generally used for cutting herbs and other plants, rounded out the trio.

As the years have gone by, the white-handled knife and the boline have essentially merged into one tool, with many Witches unaware that their altars once contained a kerfan knife. The standard athame has also absorbed many of the functions once carried out by the white-handled knife. There are still many Witches and traditions of Witchcraft that continue to use all three knives, but that’s become more and more rare.

Originally the Witch’s toolbox contained two ritual knives. There was the athame (to be used when calling the quarters, casting the circle, and celebrating the Great Rite) and the kirfane (used for everything else). White-handled knives were used for marking candles, creating other tools, cutting cords, and any other physical activity that might take place inside the circle. In time, many Witches began to feel completely comfortable using their athames for what were essentially magical acts, and discontinued their use of the kirfane.

The boline (sometimes spelled bolline and generally pronounced “bow-leen” or “bow-line”) bears some similarities to the white-handled knife, but it was originally designed for entirely different work. Like the white-handled knife, the traditional boline has a white handle, but that’s where the similarities end. The boline is sickle-shaped, resembling the traditional Druid’s tool more than a Witch’s knife. The boline was also designed to be used outside (or perhaps in an indoor garden) and not in the Witch’s circle. The kirfane was originally a ritual tool that sat on the altar as a complement to the athame.

At some point, the white-handled knife was superseded by the boline, though no one is exactly sure why. Perhaps the idea of three knives simply seemed redundant. Any cutting that was needed could be done with the boline (or even the athame) and besides, the boline was completely unique. It has that cool shape and stands in sharp contrast to the athame.

In many traditions the kirfane wasn’t a reverse-athame; it had its own specifications besides the white handle. Instead of a double-sided blade, it often had just one cutting edge. Its point was also kept as sharp as possible, all the more effective for carving into candles or other magical aids. There are some spells and rituals in this book that call for actual physical cutting; for the purists out there who would never sully their athames in such a way, they can all be done with the white-handled knife.

If you own more than one athame, it’s possible that you are already using one of your knives as a kirfane. I use one of my athames for most of my ritual “cutting” needs and another one for all the symbolic stuff. Until I wrote this book, it never would have occurred to me that one of those blades is closer to the “white-handled knife” than the traditional athame.

Both the boline and the kirfane are rather modern innovations, though they have a long history. Not surprisingly, a word very close to boline shows up in the Key of Solomon, which contains a whole host of knives. Among them, there is the bolino, a needle-like knife that doesn’t look like a boline or a kirfane. In chapter 2 of his Book of Ceremonial Magic (1915), Christian occultist A. E. Waite refers to a “bolline or sickle” and includes a drawing of the tool, which looks like a small fish-hook-shaped knife.

Waite refers to his bolline as the “most important” of a magician’s tools and includes instructions for making a bolline:

The most important to make is that called the bolline; it must be forged on the day and in the hour of Jupiter, selecting a small piece of unused steel. Set it thrice in the fire and extinguish it in the blood of a mole mixed with the juice of the pimpernel. Let this be done when the Moon is in her full light and course. On the same day and in the hour of Jupiter, fit a horn handle to the steel, shaping it with a new sword forged thrice as above in the fire.

I have little doubt that the origin of the boline in modern Witchcraft comes from Waite. Today’s boline doesn’t much resemble Waite’s drawing of the “bolline or sickle,” but it certainly matches how most of us envision a sickle.

Most bolines today have stainless steel blades, though brass is a popular alternative (and visually striking). A friend of mine suggested a boline with a ceramic blade. Ceramic is great for cutting soft vegetables since it can be made extremely sharp. The downside is that a ceramic blade is not very strong; you certainly wouldn’t want to use it to saw through anything. Another bonus is that a ceramic boline could have both a white blade and a white handle. Since it’s a knife, it’s generally associated with the element of fire (or sometimes air), but since I use mine almost exclusively outdoors, I think of it more as a tool of earth.

Many Witch traditions have specifications for the boline that are similar to those for the athame. They call for a white wooden handle, but this is a qualification I see less and less often today. Besides, practicality matters more than tradition. A boline handle can be any color and made from any material you are comfortable with. I do think that because the blade is designed specifically for cutting, it should always be made of metal (instead of wood, stone, or bone), but I’m sure there are some who object to that.

I’ve always been hesitant to use my boline in ritual because its purpose is so very different from that of the athame (or even the traditional white-handled knife). To put it simply, the boline is a tool of death. It’s used to harvest plants, and is often the instrument that ends their lives. Because of that, I prefer to keep it out of my rituals and often my spellwork. It doesn’t make any sense to me to use a tool that causes death in a healing ritual, for example. I think the early Witches made a very wise decision by separating the athame from the boline.

While researching this book, I found plenty of instances where bolines and white-handled knives were used interchangeably during ritual. I’m not sure many of those Witches stopped to reflect on the symbolism and different energies those knives were originally intended to have. If you are comfortable with using your boline in circle, by all means feel free to use it, but I’m a bit wary of the idea.

Finding a Boline

I think there’s a pretty good amount of wiggle room when it comes to finding the right boline. Though I’ve always preferred a sickle-shaped blade, many Witches own a boline that has only a slight curve to the blade. Because there’s no set rule on the blade, the boline can go beyond mere knife.

I know some Witches whose bolines are simply basic knives whose use is reserved for things outside the circle. The blades aren’t curved and the handles aren’t white; they are simply effective cutting tools, though tools that are charged and consecrated. Since the boline is more personal than other tools, this makes a lot of sense. Since we don’t bring our bolines to ritual, there’s no one around to tell people that their boline is “wrong.”

Knives with a curved blade are easy enough to find at knife stores and even at some metaphysical/Witch shops. To be honest, single-sided blades are often easier to find than double-sided ones. What’s probably most important when it comes to choosing a boline is how sharp it is. Since it’s going to be used for actual cutting, it’s important to have a knife that’s more practical than ornamental. I’ve handled many athames over the years that weren’t sharp enough to cut through a stick of butter, but that won’t work with the boline. It has to be sharp.

Because I use my boline extensively in the garden, mine isn’t even a proper knife. It’s actually more akin to a hand sickle. This means I can’t use it in the kitchen for chopping or slicing anything, but it works amazingly well outside. I love the idea of using something that ancient Druids might have used, and I like that it makes my boline completely unique from my other knives.

If you plan to use your boline a lot in the garden, hand sickles can be purchased at most hardware stores. Effective ones can be picked up for as little as ten dollars, but since it’s going to be both a garden and a magical tool, I suggest spending a little extra money and getting a really good one. When it comes to the boline, what’s really important is finding one that works for you.

Blessing a Boline

As a Witch’s tool, the boline is unique. It’s the only “standard” Witch tool that’s not designed to be used in ritual space. Bolines are meant to be used outdoors in nature (or at least our gardens). Since the boline as a tool exists “between the worlds,” I think it requires an extra blessing in addition to the usual consecration.

Before blessing your boline, consecrate it as you would an athame (there’s a ritual for that in chapter 4). Once it’s been consecrated, the only extra tool you’ll need for this boline blessing is a bowl of water. Start by taking the water and your curved knife to wherever you think your boline will get the most use. For those of us lucky enough to have a garden, this is probably where you’d want to perform this ritual. If you have a container garden, your potted plants are an ideal spot too.

Place the blade of the boline into the ground. Get as deep into the earth as you possibly can; if you can bury your boline up to the hilt, all the better. Place your hand on the boline’s handle and feel the energy of the earth coming up through it. Let your consciousness drift for a second and let your energy mingle with that of the earth, moving down through the handle, into the blade, and into the ground. As you drift downward, feel the embrace of the Goddess in the earth and the touch of the God coming from the sun.

Acknowledge them both while saying:

From the power of the sky and the energy of the earth comes new life. When those great powers unite, the magick of creation begins. I thank the Lord and the Lady for their blessings.

Look up at the sky and then back down at your boline. Think about how you will be using this tool in the months and years to come. Envision yourself harvesting herbs, vegetables, and fruit. See it as a sacred tool of the harvest and as a link to all of the Pagans and Witches who have come before you. Imagine yourself using it in a responsible manner and say:

I pledge to harvest only what I need, no more, no less. I will not waste, so therefore I will not want. May my boline be a tool of balance that keeps me in harmony with nature.

Now take your bowl or chalice of water and slowly pour the water into the earth around your boline while saying:

What I take, I shall return. I am a part of the web, not the master of it. With this boline I will reap what I have sown, and I shall do so with appreciation and humility. May the earth drink deeply from this cup I share!

Pull the boline up from the earth and set it on the ground. Take some dirt and sprinkle it on the blade and ask the Goddess for her blessings:

Great Mother, Earth Goddess, bless this blade so that it might bring me closer to your mysteries. So mote it be!

Now hold up the blade so it reflects the rays of the sun and ask the God to also bless your boline:

Horned One, Lord of the Forest, bless this blade so that it might bring me closer to your creation. So mote it be!

After receiving the blessings of the Lord and the Lady, your boline should now be ready for use.

Using a Boline

The ideal place for using a boline is outdoors. I use mine to harvest fruit, vegetables, herbs, and anything else growing that needs to be cut or pruned. Since using a boline in such a manner requires “taking” from nature, it’s usually a good idea to thank whatever you are harvesting.

When harvesting from a tree, I tend to talk directly to the tree and thank it for the fruit that it has produced. In addition to thanking the tree, I also like to present it with a little gift. I know many Witches who leave coins or other such goodies, but I’ve always preferred to be practical. I like to give my trees some fertilizer or a good, overly indulgent drink of water. I think they appreciate that more.

Sometimes harvesting something means ending the life of a particular plant. I admit, I sometimes feel guilty when I have to basically kill a plant. In such cases I tend to approach the plant reverently and with a deep sense of thanks. I also promise that I will honor the gifts they’ve given and will welcome back their descendants next spring. Many of the plants I harvest are annuals, meaning they typically die over the course of one growing season, so I think they are prepared for what’s coming. Still, I do shed a tear each year when I pluck the last pumpkin from the vine.

Before harvest time I often use my boline when digging around in my garden/yard and pruning the plants and flowers within it. Since my boline is a consecrated and charged magical tool, I think it adds a little bit of energy to my gardening experience. It also makes harvesting plants and working outdoors a sacred and holy experience.

Being a Witch means being outdoors and within nature. For many of us, getting to truly “wild” land isn’t possible, but growing some tomatoes in a pot or keeping a small herb garden in the kitchen is. Using my boline for such projects reminds me that growing things is a valid and often necessary witchy endeavor. My boline connects me to nature in ways that my other tools do not.

If your boline is more a traditional knife than a moon-shaped blade, there’s no harm in using it in the kitchen. There’s something magical about the idea of using a tool from planting to harvest to slow cooker. There are several spells in this book that call for the athame in the kitchen, but in a lot of ways the boline is an even better choice.

Ancient Druids and the Sickle

The second largest modern Pagan tradition is most likely Druidry, and it’s popular on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and many other spots throughout the world. Druidry bears a close resemblance to modern Witchcraft because there’s been a lot of sharing between the two traditions. Many of the most famous Druids of the past fifty years have also practiced the Craft. There’s been a lot of give and take between the two groups over the last hundred years, and that’s likely to continue into the future.

Modern Druidry exists in two forms. There are Druids who actively attempt to recreate the rituals of the ancient Celts in a modern context, along with Druid groups whose roots can be traced back to the types of fellowship first pioneered by the Freemasons and other fraternal orders. Neither type claims to be a direct continuation of ancient Druidry, though both kinds of Druids certainly respect and admire their long-ago forbearers.

We don’t know exactly what the Druids of two thousand years ago practiced, but some of their rites have been passed down to us by writers of the period. One of the most famous passages concerning Druids was written by the naturalist and historian Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE). Pliny’s description of Druids in white robes gathering mistletoe under the full moon has been an inspiration to many artists and modern Druids, and is one of the most compelling pictures of ancient Druid practice.

Pliny’s mention of Druids appears in his massive book Natural History in a section about mistletoe. His description of Druids is so captivating that it’s the most famous part of his work. In book 16, chapter 95, of Natural History, he writes:

Upon this occasion we must not omit to mention the admiration that is lavished upon this plant by the Gauls. The Druids—for that is the name they give to their magicians—held nothing more sacred than the mistletoe and the tree that bears it … The mistletoe, however, is but rarely found upon the robur [oak tree]; and when found, is gathered with rites replete with religious awe … This day they select because the moon, though not yet in the middle of her course, has already considerable power and influence; and they call her by a name which signifies, in their language, the all-healing. Having made all due preparation for the sacrifice and a banquet beneath the trees, they bring thither two white bulls, the horns of which are bound then for the first time. Clad in a white robe the priest ascends the tree, and cuts the mistletoe with a golden sickle, which is received by others in a white cloak. They then immolate the victims, offering up their prayers that God will render this gift of his propitious to those to whom he has so granted it.

Of most interest to us is the use of the golden sickle in the mistletoe-gathering rite.

Pliny’s Druids are obviously using a ceremonial sickle. If the blade they used was truly “golden,” it seems unlikely that it was being used on a daily basis. The modern boline is similar to the sickle, and many bolines today also have the curved blade generally associated with the sickle.

As tantalizing as Pliny’s tale is, there are no other Greek or Roman writers who mention a ceremonial Druid sickle. It’s also possible that Pliny’s information on Druids isn’t quite accurate. Pliny is a rather reliable historian when writing about things close to his home in Rome, but a bit less so the further afield his subjects are. For instance, he populated the Sahara Desert with a people he called the Blemmyis, who were headless and had their eyes and mouths on their chests.17

Even with Pliny’s limitations, as a travel writer the passage quoted here likely offers some real insights into the Druids. The Celts did honor mistletoe and oak trees and practice animal sacrifice. The “golden sickle” is a bit more suspect, but I suspect a sickle was present, though I’m not sure how golden it would have been (especially if it was used during sacrifices).

Today’s Druids don’t sacrifice animals and I’ve never seen one climb an oak tree in a white robe, but a few of them still use sickles in their rituals. Druid groups operate differently from most witchy ones, and most Druids today are members of large international organizations. Druids might be smaller in number than today’s Witches, but they are often better organized.

North America’s largest Druid organization, Ár nDraíocht Féin (A Druid Fellowship, generally known as ADF), doesn’t use the sickle at all. The Henge of Keltria, an offshoot of ADF, does still use the sickle, but only occasionally. The biggest Druid group in the world, the Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids (OBOD), has much in common with modern Witchcraft. OBOD Druids call quarters and cast circles, but they do so without a sword, an athame, or even a sickle. So while Druids have a long history with pointy things, the modern variety doesn’t use them all that much.

17. Ronald Hutton, Blood and Mistletoe: The History of the Druids in Britain (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), p. 15. For a history of the Druids from antiquity to the modern age, there is no better resource than this great book.