The Knife in

Traditional Witchcraft

There are many different types of Witchcraft in the Western world. The most common is Wicca, and the majority of the rituals and information in this book are Wiccan in nature, but that’s not the whole story. In recent years there has been a surge of interest in what’s known as Traditional Witchcraft, a tradition that also uses ceremonial blades.

Traditional Witchcraft is hard to define because there are several different competing definitions. There are all sorts of people who call themselves “Traditional Witches,” and they don’t all agree on what constitutes their tradition. Generally, Traditional Witches claim to utilize a body of knowledge different from that of Gerald Gardner and his later initiates. They also often claim that their tradition is older than the one revealed by Gardner in the early 1950s.

Oftentimes Traditional Witchcraft is influenced by cunning craft, a type of folk magick popular in Great Britain from the end of the Middle Ages right up until World War I. Cunning craft is a mixture of folk magick and information taken from books. Cunning folk were both men and women, and they provided a broad range of services. They were often employed to find lost items, heal the sick, and remove curses.

Today it’s easy to think of those folks as “Witches,” but that was not how they self-identified. Most practitioners of cunning craft were Christians and they were often called upon to remove spells and curses that people believed were cast onto them by witches. Cunning folk were occasionally persecuted for practicing magick, but were generally seen as just another part of the community. Some cunning men were even village priests!

Just like modern Witches, the cunning folk of the last five centuries used magical knives for a variety of purposes. Many of these tasks were mundane, but some were most certainly magical. The cunning folk used their knives to cut herbs for spells and potions and to carve symbols onto candles.

Many cunning folk also used their knives (and sometimes even a sword) to cast magick circles while hunting for buried treasure. The circles were important for treasure hunting because it was widely believed that ghosts or other such spirits guarded underground treasure hoards. The circle provided protection from the bad spirits and helped contribute to the idea that cunning folk often worked with the spirits of the dead. In that spirit many modern Traditional Witches work with spirits or ancestors.

Most cunning folk were literate and utilized magical texts such as the Key of Solomon to assist them in their magical endeavors. Those texts often required the use of a ritual dagger or knife. In magick both high and low, blades are nearly always present.

The most famous and influential Traditional Witch of the last sixty years was an Englishman named Roy Bowers (1931–1966), better known by his pen name, Robert Cochrane. Cochrane claimed that many members of his family had practiced a secret form of Witchcraft over the last four hundred years, and that he could trace his family’s involvement in the Craft back to the sixteenth century. Cochrane’s claims have never been substantiated, but the type of Witchcraft he practiced and inspired has been influential to many Witches. Cochrane’s original circle was known as the Clan of Tubal Cain, and many of the groups who were inspired by him have this title in their names. (Tubal Cain was a master smith in Hebrew legend.)

Much of Cochrane’s Craft was similar to other forms of Witchcraft popular in the 1960s, but there were differences too. He utilized a distinct working tool he called a stang, and it was often the centerpiece of his workings. Cochrane’s stang was often a wooden stick with two prongs or horns on top of it. The base of the stang was often wrapped in iron.

Perhaps more important to our purposes (this is a book about pointy metal things) was Cochrane’s other version of the stang. Most tools in Witchcraft can generally be found lying around one’s house, and in the case of the stang, it could generally be found lying around the barn. Cochrane’s other version of the stang was the common pitchfork, an item unlikely to attract much notice in agricultural communities (or those who do a lot of gardening today).

In Cochrane’s version of Witchcraft, the stang served as a visible symbol of the Horned God (which is especially fitting if one looks at the Devil as a corrupted version of earlier horned gods such as the Greek Pan). As someone who utilizes a stang on occasion during ritual, I can attest to the fact that it’s a very powerful-looking ritual tool. I’m sure Cochrane saw it in a similar fashion since he often used his stang as a focal point during ritual. Many Witches who use the stang also decorate it to reflect the Wheel of the Year.

In addition to the stang, Cochrane used most of the “traditional” tools we associate with Witchcraft today, including the knife. Originally Cochrane referred to his blade as an athame, 20 like most Witches in the early 1960s. The word appears less frequently in his later writings, generally replaced by the more generic-sounding “knife.” Most of those who follow the teachings of Cochrane today simply call their blades a “knife.”

Cochrane used his knife in a way similar to that of the athame. It was used to enact the symbolic Great Rite and was said to represent masculine energy. It was also used to bless cakes and ale and to assist in the calling of the four elements. Cochrane-inspired covens (or cuveens) often share one “coven knife” during ritual. This is different from many Wiccan-style groups that encourage individual ownership of an athame. Indeed, I’m unaware of any Wiccan-style groups that share a coven athame like Cochrane’s groups share the knife.

While there are many similarities between Cochrane’s Traditional Witchcraft and modern Wicca, some of the ritual differences between the two are extremely interesting, and often involve the knife. As I wrote at the beginning of this chapter, there are many different types of Witchcraft labeled “traditional,” but the strain I’m most familiar with is Cochrane’s, so those are the rituals included in this book. All of the rites included here were directly inspired by the writings of Cochrane himself and those who carry on his legacy.

Traditional Witchcraft Rituals

with the Knife and the Sword

Traditional Witchcraft often operates with a different running order than other forms of Witchcraft. Instead of calling the quarters and casting the circle at the beginning of ritual, this happens toward the middle, after the Goddess and the God have been invoked. Most significantly, the knife is not used for casting the circle but is actively involved with the four quarters.

The knife is utilized in a more familiar way during the Great Rite and the blessing of the cakes and ale. Many of the “flourishes” in those rites are different from the ones previously shared in this book, but the ideas behind them are generally the same. All of the rituals outlined here can easily be adapted for use in more Wiccan-style rites.

Since this is not a book about Traditional Witchcraft, we will only be touching on rites that involve the knife or sword; but for those who want to dig a bit deeper, I feel as if I should offer an outline of Cochrane’s rites. When Cochrane passed in 1966, he did so without leaving behind any detailed accounts of his working. As a result, those who practice his Craft rely on his letters and the works of those who performed ritual with him (Witches such as Evan John Jones and Doreen Valiente).

Using those sources, my Cochrane-inspired rites proceed in this order: fashioning the bridge, opening prayer, coven cleansing, blessing, placement of the stang and cauldron/call to the Goddess and the God, calling the quarters, casting the circle, working, cakes and ale, closing the circle, and finally, releasing the bridge. This is most certainly not how every Traditional Witch conducts their rituals, but it is my approximation after studying the letters of Cochrane. The bits in this book can be used to create a larger Traditional Witch ritual, or they can simply be inserted into more common forms of Craft. They are effective and offer an interesting change of pace for most Witches.

Instead of the terms high priestess and high priest, Cochrane used the terms Maid and Magister. Since those are what he used, it’s what I’ll be using here (even though my wife and high priestess does not like being referred to as a “Maid”—proceed with caution if you use that term). Many of the groups that emerged from the forge of Tubal Cain utilize other roles in their rituals, but for simplicity’s sake I’ve kept everything between Maid and Magister. For those interested in Traditional Witchcraft, check out the bibliography and further reading list for more information.

Fashioning the Bridge

Cochrane’s rituals were a journey into another realm, and he generally began his rituals by having the members of his coven walk over a symbolic bridge. His bridge was the pathway between the mundane world and the magical one, and signified entry into sacred space. That sacred space is sometimes referred to as the Spiral Castle, an idea taken from the book The White Goddess by the English poet Robert Graves (1895–1985).

Fashioning the bridge is a short rite, but an effective one, and generally gets the attention of everyone in the coven. Instead of beginning the ritual in a circle, the Magister and the Maid should stand at the threshold of the ritual space, with the coven outside that space looking in. When circumstances permit, the bridge should be located in the north, but that’s not always possible. In my coven we create the bridge at our ritual room’s entry point.21

The Magister should be carrying the coven sword and the Maid the broom. Maid and Magister should be focused on creating a pathway into magical space. When performing this rite, I try to imagine my sword glowing a little bit while charging it with magical energy. The Maid generally does the same.

Looking into the eyes of the coven, the Magister should dramatically hold up his sword and then set it down while saying:

I lay down this sword so that we might walk in other realms.

The Maid holds her broom aloft and lays it over the sword, saying:

And I this broom. Conjoined and bound together, they represent the most ancient of magics.

The Magister and Maid step back from the newly created bridge and bid the coven entrance into the rite. The Magister welcomes them in with the following words:

Step across this gate and come into the Otherworld, the Spiral Castle where all true Witches tread. So be it done!

Once the bridge has been constructed, the ritual proceeds in whatever way the coven chooses. The Magister, Maid, and coven return to the bridge near the conclusion of the rite.

Once all the divine forces within the circle have been dismissed, the Magister and the Maid approach the bridge. Slowly the Maid picks up the broom and holds it to her heart. The Magister then does the same with the sword. Looking into the eyes of the Maid, the Magister says:

That which was joined is now asunder.

The Maid replies:

The gate is now open. Let all who have journeyed into the mysteries be free to depart this place. So be it done!

The coven is now allowed to leave the ritual space and the rite is over.

Calling the Quarters

Invoking the four quarters in Cochrane’s version of Traditional Witchcraft requires both a cauldron and an athame. Begin by filling the cauldron (if you don’t have a copper or iron cauldron, a bowl also works) with fresh spring water from a pitcher or other large container. The Maid fills the cauldron while saying:

I fill this cauldron so we might glimpse the cauldron of Cerridwen that is the cup of life and immortality. Within her waters we begin our journey to the Otherworld, where true witchery dwells. We are the children of the Goddess and this cauldron is her symbol.

Instead of calling watchtowers or elemental energies, Cochrane called to four different gods at each of the cardinal points of the compass. He saw each of these gods as living in their own space (or castle). When invoked, they help Witches journey to the other side and walk between the worlds. In his cosmology, the elements of earth, air, and water are seen as feminine attributes; as a result, the Maid calls the gods there. The Magister calls to fire in the east.22

After each god is called, the Magister dips his knife into the cauldron and flips the water upon the blade toward each of the four quarters. I do this near the outside of the circle instead of in the middle by the altar. The “ritual walk” adds a bit of drama to the rite and ensures that the gods called to enter the circle in the proper space. Sharing the water from the Goddess cauldron at each of the four quarters symbolizes her power being necessary to move from one world to the next and adds some feminine energy to a rite focused mainly on four gods.

After the water is poured into the cauldron, the Magister and the Maid should stand in the center of the circle by the altar. The Magister begins the rite by saying:

We begin our journey at a castle in the east surrounded by fire and ruled by Lacet.

The Magister then sticks his knife into the cauldron and walks to the east, flicking the water from the knife when he reaches the perimeter of the circle. This action is repeated at each of the cardinal points after the invocations to the gods are read.

Lacet is another name for Lugh, the shining one of Celtic myth. Here he is invoked as a god of the sun and of knowledge. Some writers have also linked him to Lucifer, a figure that often comes up in Traditional Witchcraft. This Lucifer is not the Christian Devil but another figure of wisdom.

The Magister now approaches the altar again. When he arrives, the Maid continues the rite by saying:

Our next journey is to a castle in the south surrounded by forests of trees and ruled by Carenos.

Carenos here is a variant spelling of Cernunnos, the Gaulish-Celtic god of hunting and the natural world. Cernunnos is one of the most popular aspects of the Horned God.

The Maid and the Magister now turn to the west, where the god Nodens is invoked:

On to the west and a castle deep in the ocean ruled by Nodens.

Nodens is a Celtic god native to the British Isles who is often associated with the sea and healing. Unlike the other gods who are a part of this rite, Nodens is not a variant spelling.

The final act of the rite is in the north, and again the Maid calls to the god being invoked:

And finally to the north and a castle built in the sky and ruled by Tettans.

Tettans sounds very much like a group of fairies or people but is most likely an alternate spelling of Toutais, another Celtic deity (and one who has been known to show up in the French comic Asterix). He was generally seen as a god of protection and hunting and was often seen as similar to the Greek god Hermes. That’s possibly why he shows up here associated with the element of air.

I’ve found no “quarter dismissal” in the works of Cochrane equal to the calls shared here. If you want to dismiss the energies called here in a symbolic way, I suggest starting in the north. Have the Magister walk to the cardinal point and then hold aloft his knife while the Maid says:

We now leave behind the castle in the sky and its ruler, Tettans.

The Magister then walks back to the cauldron and ceremonially shakes the water collected there back into the cauldron.

This process is then repeated at the rest of the quarters, with the Maid offering the appropriate dismissals: We now leave behind the castle in the ocean and its ruler, Nodens. We now leave behind the castle surrounded by forests ruled by Carenos. The Magister “collects” the water he shared at each of the cardinal points and then “returns” it to the cauldron. Finally the Magister says:

We now leave behind the castle of fire and its ruler, Lacet.

He then approaches the east and walks back to the cauldron.

After the rulers of the castles have been dismissed, the water in the cauldron is then either spilled upon the ground or returned to the pitcher it came from. Then pitcher is taken outside and the water shared with the earth at the ritual’s conclusion. The Maid then says:

From the earth it came and from the earth it will return when we depart this place. In the name of the Goddess, so be it done!

The Great Rite/Cakes and Ale

Symbolically there’s no difference between the Great Rite as practiced in Cochrane’s Craft and the one practiced in Wicca. There are some slight changes in the ritual, and many of those changes involve how the athame as used. For this rite you will need a knife, cup, sharpening stone, and mirror. If the ritual is inside, you’ll also need a lantern or candle. The cup should contain whatever beverage you are using for cakes and ale. Since Cochrane used the cup’s content to symbolize blood and sacrifice, the drink should be red, preferably red wine or cranberry juice.

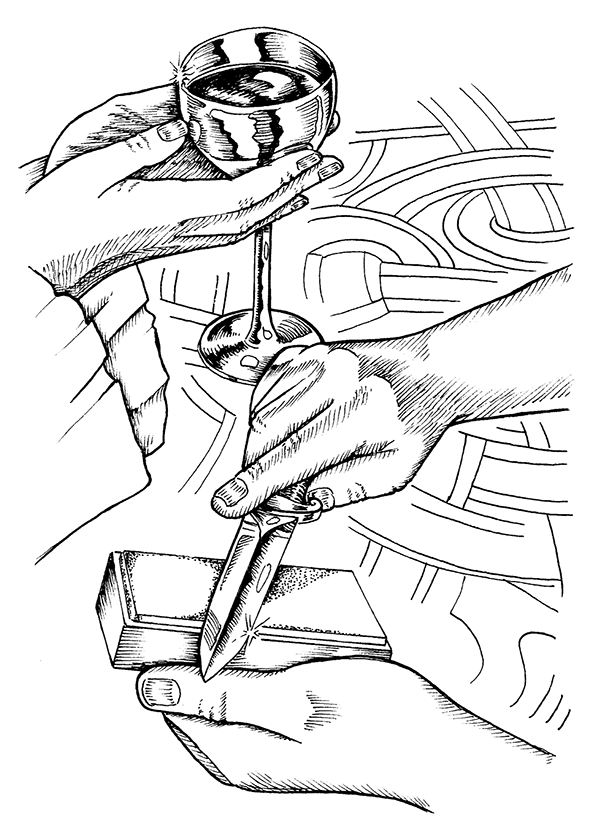

The rite starts with the Maid picking up the cup and, if indoors, the mirror. The Magister stands beside her with his knife and the candle (or lantern). The Maid then holds the mirror near the cup’s rim, angled to reflect the light of the candle into the cup. The Magister holds the candle up near the mirror and says to the Maid:

I bring you the light of the moon.

The Maid replies:

For it brings us the light of the Lady.

(If the ritual is outdoors, the Magister picks up the mirror and uses it to reflect the moon’s light into the cup.)

As the light reflects into the cup, the Maid calls to the Goddess and reflects on the Great Rite:

Great Goddess, I call to you now in our ritual to tear apart the veil that separates us. The knife is to the male; the cup is to the female. Joined together, they symbolize new possibilities and the continuation of all life. This cup is a symbol of your abundance; the knife symbolizes the phallic power of the Horned One, your lover and loved.

The Magister then sets down the candle (or mirror, if outdoors) and picks up a sharpening stone while saying:

Horned One, join us in the charging of this drink. In your union with the Great Goddess, the two of you become one and reveal to us life’s mysteries. By drinking from this cup may we experience the grace and mysteries of the gods.

The Magister then sharpens his knife three times upon the sharpening stone before plunging it into the cup. The knife is then used to stir the contents of the cup three times. When this is complete, he splashes a bit of the wine at each of the four cardinal points, beginning in the east and proceeding clockwise (south, west, and finally north).

When the Magister returns to the center altar, he and the Maid kiss and then say in unison, So be it done. Then they both drink from the cup. The Maid then sets down the cup and picks up the plate of cakes (or bread, or whatever you choose to eat during ritual). The Maid stands in front of the Magister in a pose suggesting that she is offering the cakes to him and says:

Maid holding the cup while the Magister sharpens his blade nearby

Maid holding the cup while the Magister sharpens his blade nearby

I call to the Old Gods that they might look upon this bread and witness our sacrifice unto them. This gift is given to the gods and to those of this coven so that we might better understand the mysteries. As Witches, this is our right and privilege. By the call of blood to blood, we eat and share this bread. So be it done!

The Magister then takes his knife and touches each cake with the point while saying:

Through the power of this knife

We are led to knowledge and life.

The Lady shares with us the grain

Reaped from the earth with joy and pain.

From the ground and dust this bread came

And to that ground will be for us the same.

But from death also comes rebirth,

As it ever is upon the earth!

In the names of they who are one,

We Witches all say, be it done!

Then the Maid and the Magister each take a piece of bread from the plate and eat it. The plate is then handed back to the Magister while the Maid takes the cup. Before leaving to distribute the wine and bread to the rest of the coven, they stare into each other’s eyes and say:

In the Old One’s name we eat this bread

With great terror and fearful dread.

We drink this in our Lady’s name,

And she’ll gather us home again. 23

After all have drank from the cup and eaten the bread, the ritual proceeds. Be sure to save some bread and wine to offer the gods when your ritual is over. If the rite is outdoors, this can be left on the ground during the ceremony. If the ritual is indoors, it should be done once the rite has ended.

Jenya T. Beachy

there is a line of Witchcraft born on the West Coast of the United States only nominally influenced by the goings-on in Europe. That tradition is known as the Feri Tradition and was begun by Victor and Cora Anderson. Today there are many different traditions in the Feri family tree.

In the Shapeshifter line of Feri Tradition, there is a focus on relationships and perspective; we understand that all things have their corollary within us. Our skin is a point of reference from which the universe expands and contracts, from the infinitesimally small to the immeasurably big. The edge of us separates the interior world from the exterior world and is the blade of our individuality, shaping our lives as we go.

The Witch’s knife is a tool of power. To wield it safely, we must become adept at managing our own power. We take responsibility for our part in the circumstances of our lives. We sort what is within us from what is outside of us. We attend to our complexes, and the blade assists us in that work.

Our knife is a real device of cutting, of separating this thing from that, and it is dangerous. You might cut away something you did not intend to part from. You might hurt someone.

There is nothing inherently wrong with this.

Sometimes we must be rebroken so that we can heal up right this time. Sometimes we must open a wound to let the infection drain. We need sunlight and air on our hurts to help them heal. The knife can open a path for that light to travel. The knife can be the path, reflective and clean.

We understand the value of being sharp and flexible so we can point and thrust with confidence. To have this confidence, we learn to know ourselves. The cultivation of our will allows us to stand in the fires of our complexes, trusting that we will survive.

The knife is the tool of will.

Meditating on the events in our lives that have burned us, pounded us, folded us, reminds us that adversity shapes us. Recalling the cool relief of the gods’ sweet waters reminds us that both ease and challenge are gifts they give their children.

The knife can support, keeping the back straight and shoulders square. It aligns itself to the body and we may walk with the blade against our backbone, providing us with a framework.

The knife can defend. Laid across the threshold, it keeps intruders away. Worn on the belt, it reminds us that we are capable of doing what is needed.

When walking into the circle, carry the Witch’s blade, and leave the shield at the door. Enter sacred space unencumbered by defensiveness. But always come with power. And recognize the power of brothers and sisters of the Craft.

Blessed be your strength.

Jenya T. Beachy

www.jenyatbeachy.com

20. John of Monmouth, with Gillian Spraggs and Shani Oates, Genuine Witchcraft Is Explained: The Secret History of the Royal Windsor Coven and the Regency (Somerset, UK: Capall Bann, 2012), p. 418.

21. Evan John Jones and Doreen Valiente, Witchcraft: A Tradition Renewed (Custer, WA: Phoenix Publishing, 1990), p. 123. The ritual seen here is adapted from the work of Jones, along with some of Cochrane’s letters as found in John of Monmouth’s Genuine Witchcraft Is Explained.

22. Ann Finnin, The Forge of Tubal Cain (Sunland, CA: Pendraig Publishing, 2008), pp. 43–44. I’m indebted to Finnin’s book for helping me find the gods behind the names. The ritual here is adapted from Finnin’s book and Cochrane’s letters.

23. According to Michael Howard that bit of rhyme is from an old “Scottish Craft Source.” Michael Howard, Robert Cochrane The Magister of the Clan, from “Pagan Dawn” magazine, Lammas 2007. It appears in Doreen Valiente’s The Rebirth of Witchcraft, Phoenix Publishing, 1989, pg. 123.