Colourful corals can be found all around the Mediterranean coastline and offshore islands.

THE MEDITERRANEAN

Known as the ‘Cradle of Civilization’, the Mediterranean Sea is now set in a massive flooded depression in the earth’s crust formed over millennia. This vast expanse of water is almost completely landlocked, stretching from the Straits of Gibraltar in the west to the coasts of Turkey, Syria and Israel in the East. The Mediterranean both links and divides three continents, Europe, Africa and Asia. The varied depths of this basin also support varying communities of marine life and although all of the species found in the Mediterranean contribute to the whole, we shall only concern ourselves with what we can see, practically and with the least effort, whether it be from swimming, snorkelling, scuba diving, or even fishing and sailing.

With water temperatures that never drop below 10°C, the Mediterranean has remained fairly isolated over the years and has evolved a distinct ecosystem only troubled by man’s intrusion. The region is complex and diverse in its geography, history and climate, with much of what we know and see only coming from the northern shores and around many of the islands.

Known for its very singular climate, the present shores of the Mediterranean were roughly formed five million years ago; however, it took early form over twenty million years ago when the western shores were still closed and the eastern end was still linked to the vast primeval Tethys Sea. As the years passed, Africa slipped anticlockwise, Arabia split from Africa forming the Red Sea and the eastern stretches of the Mediterranean also became landlocked. Whilst this continental movement was progressing, the land areas were gradually ‘crumpled’ up forming a ring of mountains which now comprise the Sierra Nevada, the Alps, the Atlas Mountains, the Dinaric Alps, the Rhodope Mountains, the Akhdar Heights and the Taurus Mountains. Over the subsequent two or three million years, the now-landlocked Mediterranean filled and evaporated several times as the earth’s crust shifted, often leaving gigantic salt marshes and mud pools where dinosaurs once roamed.

As far as can be agreed between scientists, about five million years ago, there was a massive cataclysmic earthquake which opened up the Gibraltar sill, and the Atlantic Ocean poured into the basin taking almost a century to fill. Today, this connection to the Atlantic Ocean is still very evident and water pours into the Mediterranean at approximately 4km/h (2.5mph) in a layer from 75 to 300m (250–1,000ft) deep. This sea water gradually evaporates and the heavier, more salty water sinks and eventually flows back out through the Straits of Gibraltar, taking around eighty years to replenish the water column.

This has had several knock-on effects, one of which is the reduced amount of plankton to be found in the Mediterranean and what plankton there is, quite often flows back out into the Atlantic in the deeper ocean currents. This ultimately produces less marine life, but also clear water in general. As always, there are notable exceptions and wherever there is a large river run-off there will be periodic algal blooms which reduce visibility. Rough seas in shallow areas also contribute to poor visibility, but in general one should expect underwater visibility of about 30 to 50m (100–165ft).

Colourful corals can be found all around the Mediterranean coastline and offshore islands.

A Sea of Seas

Although not truly one sea, but several joined together, the individual seas are defined by the surrounding land masses formed when the earth’s crust collided. There are two principal areas known as the Eastern and Western Mediterranean roughly separated by the mid-ocean ridge which runs from Italy to the African coast. The Alboran Sea is found in the west, connecting to the Algerian Sea or Balearic Basin between Algeria, Sardinia, Spain and France. The Gulf of Lyons and the Ligurian Sea stretch along the southern coast of France, the Tyrrhenian Sea surrounded by Corsica and Sardinia to the west, Italy to the east and Sicily to the south. The two most famous of the Mediterranean’s seas are the Adriatic and the Aegean; it is on these seas that the history of mankind spread from the old to the new worlds. The Gulf of Trieste, in the northern area of the Adriatic Sea, is formed with Italy on its west, Croatia and Albania to its east; further south the Ionian Sea separates the southern coasts of Italy and Sicily with the Maltese islands to the west with Greece and its many islands to the east. Separating Greece and Turkey is the Aegean Sea which is connected to the Black Sea in the north-east by the Dardanelles, Sea of Marmara and the Bosporus. In the eastern reaches can be found the Levant Sea bordered by Turkey and the islands of Crete and Cyprus to the north and Syria, the Lebanon and Israel to the east, with Egypt and Libya to the south. The Ionian Sea and the Levant Sea are roughly divided by a shallow stretch of water sometimes referred to as the Libyan Sea. The Ionian basin is the deepest part of the Mediterranean at 5,121m (17,000ft). In Egypt, of course, can be found the man-made Suez Canal, opened in 1869, which links the Mediterranean with the Red Sea.

Corfu, in the Greek Islands, is a popular tourist destination.

Man’s Impact

Bounded by mountains, man has made his impact mainly on the narrow coastal plain some 20 to 30km (13–20 miles) wide and in some areas of southern France and northern Italy, man has literally carved a space from the mountains themselves. With the one notable exception along the North African coast, virtually all of the Mediterranean’s population can be found along this narrow coastal strip and its associated islands. Much of the coastal plain was dominated by mosquito-infested swamps and history tells of the canal and irrigation systems which drained the swamps and irrigated the land for cultivation, thereby virtually eradicating malaria. Much of the original forest has been cut down by man, leaving a rather sparse scrubby landscape.

The Mediterranean basin and surrounding countries have some 350 million people; 135 million of them live around its shores. Economic and industrial growth has resulted in vastly increased pollution levels. The need to feed this increasing population, and its annual tourist trade of over 100 million visitors, has put further strain on the sea and its marine life. Much of the original coastline has been irrevocably changed by man’s expansion and development with yacht marinas, harbours and housing developments. Small countries such as Monaco have now lost some 75 per cent of their original coastline. The Mediterranean Sea is undoubtedly one of the world’s most threatened seas, owing solely to the increased demand on its natural resources primarily through pollution from homes, industry and intensive agricultural methods. Fortunately, the fresh seawater influx from the Atlantic has managed to stave off much of its demise, at least for the time being.

Diver and Dusky Grouper Epinephelus marginatus.

Carpet Algae

Even whilst the major problems of pollution are now being taken on board by the Mediterranean’s surrounding countries, the impact on the local sea environment is actually very small considering the size of the Mediterranean Sea. Small areas such as around Venice and the northern Adriatic, sections of the Greek coast and parts of Tunisia are under increased threat owing to tourism demands, but this is usually on a temporary seasonal basis. The marine life does regenerate in these areas with seasonal changes. However, if man’s impact was not enough in altering and destroying the coastline, there is now a new threat, placed once more at the door of one of the world’s most influential men who brought the sea and its awareness to our very homes through the media of television, engineering and photography.

Jacques Yves Cousteau was one of the primary men involved in the invention of the aqualung, that singular device which has allowed man’s (shallow) exploration of the seas to expand into a worldwide sport. His Marine Institute in Monte Carlo in the principality of Monaco was at the forefront of marine exploration and the understanding of the environment. In 1984, whilst Jacques Cousteau was still a director of the institute, a small patch of an alga called Caulerpa taxifolia was discovered beneath one of the windows of the marine institute. This alga, a native of Martin Bay, Brisbane, in Australia was reared as an aquarium alga for tropical fish and was first reported in Europe (in Stuttgart Aquarium) in 1969. The alga, although certainly not genetically modified, had inevitably undergone some genetic mutation in the closed environment of the institute’s aquaria. It would appear that an aquarium and its contents were emptied out of the marine institute’s windows and this alga, hitherto unknown in the Mediterranean, started to grow.

This act, originally accepted by the authorities, was soon dismissed as it was thought that the alga could not survive in the northern Mediterranean’s colder water temperatures during the winter months. The director of the institute, Professor Doumenge, stated that this was purely a temporary phenomenon. However, as the alga started to spread, the act was denied by the French authorities as being some import either owing to global warming or even a Lessepsian visitor via the Suez Canal from the Red Sea.

It was soon discovered that not only were there no known predators of this alga, but that it spread through fragmentation. This spread was entirely owing to man’s influence again, whereby ships’ anchors and chains and fishermen’s nets were inadvertently dragged through it, breaking off the leaves and stems: and when the offending equipment was put back into the sea in another section of the coast, the alga immediately started to grow. The Côte d’Azur was soon dotted with this rapidly spreading alga. Professor Alexandre Meinesz, a biologist from the University of Nice, was called in to assess the probable damage and subsequent spread of the alga. After 18 months of intensive research, Meinesz concluded that there was no way of stopping this ecological disaster. Six years later, Professor Meinesz stated that Caulerpa taxifolia was like a metastasizing cancer whose spread could not be halted and which could eradicate all life. He said ‘The water of the Mediterranean does not drop below 10°C; at this temperature, the alga is in stasis and can survive quite happily for over three months; at 15°C, the alga starts to grow quite rapidly; at 20°C, Caulerpa grows at over 3cm (1in) a day’. One of the most ironic factors is that Monaco promotes itself as a leading country in marine conservation, yet 75 per cent of its coastline is totally destroyed by development and now a further 90 per cent of the seabed is totally wiped out by Caulerpa.

Typical reef with Chromis Chromis chromis and starfish.

In just five years, the 1m (3ft 3in) patch had already grown to one hectare. By 1990, it was discovered by divers off Cape Martin on the Italian border and this initial area now covers over 3ha. The number of reported cases increased tenfold in the next year. In 1992, the alga was discovered in Majorca, Italy and Corsica, covering an approximate area of 420ha. By 1997, it was found in Croatia around Split, Messina in Sicily, the island of Elba and now covers 4,700ha. At the same time 300ha of small patches of Caulerpa taxifolia were found at Sousse in Tunisia and by 2001, this area had expanded to over 13,000ha. Whenever new sites are found by divers or reported by yachtsmen or fishermen, the report is verified by the university and added to the mapping of ‘Carpet Algae’.

Outbreaks of Caulerpa taxifolia have since been discovered off San Diego in California and in New Zealand. UNESCO have been informed of the catastrophic effect that the alga is having on the future of the Mediterranean, but as yet, the French authorities have still not come up with the cash or the personnel to try and extract the weed from the sea. One way of killing the plant is by spreading a large black plastic sheet over the affected area and then treating the alga with chlorine. This also kills off all other types of life, but at least the regeneration over time by Mediterranean species is preferable to Caulerpa.

The alga is not only overtaking all local marine life; as a by-product of its growth, it creates a mud residue, further smothering this fragile ecosystem. A few small nudibranchs have been discovered that feed on this alga; but nowhere near the numbers needed to halt the spread. A few small bream are starting to eat the alga, however, the plant is so toxic that it will take several generations of fish before they are immune. Then there is the problem of human health, should these toxic fish appear on the fish market.

However, early indications do show that the plant can be killed off by various methods and these trials have been successful in California and some areas of Spain. The sea slug Elysia is known to eat the alga exclusively and several types of copepods also thrive on the alga. It is hoped that with continued monitoring and the immediate response by all Mediterranean government agencies, this ecological disaster in the making may be averted.

The Habitats

Corals are not overly evident in the Mediterranean and owing to the changing water temperatures during the year, there are no true coral reefs, made up of the stony hard corals more associated with tropical coral reefs. As such, the rocky ‘reefs’ are generally composed of ancient limestone blocks from some past age when corals were more prevalent in the Mediterranean. These are now colonized by a living mantle of a mixture of small corals, sea fans, sponges, other cnidarians and various algae. Rocky coastlines and small islands have become encrusted with marine life and many species are found only in the Mediterranean. Much of the classification of the world’s marine animals has come from the early observations made in the Mediterranean.

The habitats are as diverse as they are in any specialized environment and, although there are some very deep basins in this sea, we shall only concern ourselves with the veneer, which we are able to see whilst visiting this ancient sea whether by scuba diving, snorkelling or rock-pooling.

Rockpools

These areas found after a receding tide are a mini oasis of life, often containing creatures, which are able to withstand both a rapid change in salinity (after heavy rainfall in a shallow pool) and differences in water temperature (such as at the height of the summer when the water temperature in shallow pools can rise alarmingly for the 6–8 hours before it gets covered by the advancing tide once more).

Sand

Typically, worm casts of marine worms are seen in most places. The tracks of marine snails and other creatures are also found, and this region is home to flounders, skate and rays. Many burrowing creatures also make this habitat home, such as starfish, urchins, anemones, eels and gurnard. Many beaches on the east coast of Spain, Syria, Lebanon and Israel, and much of North Africa, are some of the best beaches in the Mediterranean and their pure white sands are wonderful. Many islands have huge sand dunes formed over millennia as wind-blown sand piles up on the shore.

Mgarr Ix-Xini, Gozo.

Mud

Deeper sea-beds and those affected by river run-off build up a muddy seabed owing to the amount of detritus, which gets washed into them during periodic winter storms and heavy rainfall. Burrowing animals such as various molluscs, sea pens, mud crabs, brittle starfish, fireworks anemones and burrowing anemones are typical of this habitat and are all excellent photographic subjects.

Rocky Shores

These offer a firm substrate base for algae and other sedentary organisms to attach. The particular selection of marine life found will depend on the type of rock. Some soft rocks can be bored into whilst other glaciated granitic rocks only have a slight scattering of animals as there is nothing for them to get a firm grip on. Exposed locations will always be beaten badly by adverse weather conditions and this factor will also determine the types of marine life found. Chitons, sea urchins, limpets and barnacles are perhaps the most common rocky shore inhabitants.

The Blue Hole, Dwejra, Gozo.

Diver exploring a cavern.

Rocky Cliffs

Submarine cliffs are well known for their colourful fields of jewel anemones, underhanging ledges covered in parazoanthids, huge forests of red and yellow sea fans, tube worms, sea squirts and other more sedentary creatures. But it is more the nature of the habitat which is appealing to divers, as there are often caves and caverns associated with these cliff faces, that when combined with a deep vertical wall, undoubtedly increase the enjoyment of the dive.

Caves and Caverns

Wherever the coastline is made up of a mixture of ancient limestone or sandstone and where geological upheaval has shifted the earth’s rock strata, caves and caverns are found. Some of the most spectacular are found in north-eastern Spain, the Balearics, Corsica and Sardinia, Malta and Gozo. Huge vertical clefts cut through headlands and tunnels harbour marine species which might otherwise only be found in very deep water. Creatures which favour these dark conditions are sponges, slipper lobsters, small shrimps and precious red corals.

Shipwrecks

Well, we all know the attraction of such edifices, but these are important habitats, quite often found in areas which would be otherwise rather poor in marine life. Wrecks provide an important holdfast for soft corals, sea fans, sponges, sea squirts, algae and are also home to many different species of commercial fish. Many of the wrecks are, however, in deep water and quite often in areas of strong tidal currents. This not only limits the diver intrusion (which personally I feel is a good thing), but these wrecks would not have the same amount of marine-life colonization without those limiting factors.

Piers

The most obvious of the man-made structures which abut the seashore, the piers and breakwaters found around the Mediterranean are quite often the only shore access on many stretches of coastline, as man has irrevocably changed the original coastline in the pursuit of more living space, commercial enterprise and tourism facilities. These structures have evolved over the centuries as boat traffic has altered in shape, size and frequency of visits. When all else fails and you want a reasonable dive in fair conditions with a super abundance of marine life, then the piers and breakwaters will give you an abundance of marine life, usually including octopus, cuttlefish, anemones, sponges, mussels and simply tons of other invertebrates which live on or in the encrusting algae.

Posidonia

Fields of Posidonia oceanica (Neptune Grass) are very typical of most Mediterranean habitats and are ‘indicators’ (indicating the presence) of clear, clean, oxygen-rich water. Posidonia meadows are important nurseries for fish and shellfish and are home to many other associated species. The presence of Posidonia meadows on the seabed are a vital and indispensable habitat.

Caulerpa

Fields of the newly introduced Caulerpa taxifolia, on the other hand, are seen as a plague along the southern coast of France, Monaco, Corsica and Majorca. This introduced species is spreading uncontrolled through the Mediterranean, smothering indigenous species of Posidonia and other beneficial algae. The presence of Caulerpa means that all of the (local) marine life species and habitats are under severe threat of extinction.

Tidal Rapids

Common in a number of localities between various islands, tidal rapids are home to sponges, algae and other invertebrates which feed on the swiftly moving plankton passing on their way four times each day. Here the seabed is a mass of life and is considered a high impact zone.

PROJECT AWARE

Ten ways a diver can protect the Aquatic realm (produced by the Professional Association of Diving Instructors – PADI):

Dive carefully in fragile aquatic ecosystems, such as coral reefs.

Dive carefully in fragile aquatic ecosystems, such as coral reefs.

Be aware of your body and equipment placement when diving.

Be aware of your body and equipment placement when diving.

Keep your diving skills sharp with continuing education.

Keep your diving skills sharp with continuing education.

Consider your impact on aquatic life through your interactions.

Consider your impact on aquatic life through your interactions.

Understand and respect underwater life.

Understand and respect underwater life.

Resist the urge to collect souvenirs.

Resist the urge to collect souvenirs.

If you hunt and/or gather game, obey all fish and game laws.

If you hunt and/or gather game, obey all fish and game laws.

Report environmental disturbances or destruction of your dive sites.

Report environmental disturbances or destruction of your dive sites.

Be a role model for other divers in diving and non-diving interaction with the environment.

Be a role model for other divers in diving and non-diving interaction with the environment.

Get involved in local environmental activities and issues.

Get involved in local environmental activities and issues.

An evening dive.

Reef Conservation and the Tourist

Marine conservation is not new in the Mediterranean. Most of her bordering countries have specific marine parks, many of them over twenty years old, providing important nursery areas for many different groups of fish. Commercial fishing is still concentrated at the perimeter of these marine parks, as the protected areas can only support so much marine life, allowing the ‘overspill’ to be fished.

Unfortunately, many important habitats and breeding areas have already been severely depleted and in some cases totally destroyed. Offshore islands have generally been spared from man’s commercial activities. However, the coastline bordering the Mediterranean has been under threat since man first inhabited her shores. Many offshore reefs and rocky shoals have been overfished. The catches of fish in general have been reduced to alarming levels and traditional fisheries have collapsed in many areas.

The traditional tuna trapping or mattanza (from the Spanish word for ‘slaughter’) in Sicily and Sardinia still occurs each year as the common tuna Thunnus thynnus migrate from the Atlantic to their spawning grounds in the Mediterranean. These catches are now affected by Asian long-liners which catch huge quantities of tuna and other large pelagics without reference to any authority in the Mediterranean.

More insidious fishing methods have also affected the Mediterranean’s fragile ecosystems. Aquaculture has grown alarmingly, as the ever-increasing population and tourists require feeding. Some fish farms require huge amounts of fish meal subsequently contaminating the surrounding seas with nutrient-rich waste products. Grey mullet fisheries in Egypt have been successful, as these fish are vegetarian and also feed on detritus.

Old Tuna anchors, Tarifa, Spain.

Mussel and oyster culture is responsible for the introduction of a further sixty species of algae from the Japanese archipelago, all of which have been released into the wild from the seedling stocks imported from the country. Many people depend on the sea for their livelihood, yet even these are constantly under threat from the more commercial aspects of fishing for the mass market.

Thankfully, most countries now accept that a successful tourist industry relies on strict conservation policies and the protection of natural wetlands and fisheries. For this industry to succeed and prosper, tourists also have to be aware of the impact which even they can make on small areas, therefore education at all levels is vitally important. Membership of conservation agencies is always a clear step into the understanding and protection of the marine habitats.

Endangered Species

A number of marine species in the Mediterranean are threatened, principally due to the acts of man. Although pollution will always head up one of the main causes for the loss of a species in a specific area, it is so localized that this is rarely the case, as more strict antipollution measures have also helped clean up much of the coastline. The dangers are much more direct owing to the physical nature of the cause. Sport spear fishing has wrecked havoc on local inshore populations of large fish with a more sedentary nature such as the grouper. Overfishing and the systematic plunder of fishery resources have resulted in massive reductions in brown meagre, tuna, grouper and crayfish. Trophy catches such as the giant Mother of Pearl File Clam or the collection of living skeletons (precious Red Coral) for the jewellery trade have all had a detrimental effect on the ecosystem.

Fish waiting for market, Tarifa, Spain.

Local destruction and degradation of seagrass meadows with the construction of new ports and marinas has led to a far more insidious threat from increased tourism, where repeated use of ships’ anchors, devastating use of fishing gear and increased (local) pollution have all led to the loss of many Posidonia meadows, as they are unable to reclaim lost areas. Couple this with the alarming rate at which Caulerpa taxifolia is covering the northern Mediterranean shores, and it can be argued that all of the Mediterranean species are under threat.

Red Coral Corallium rubrum

Divers still lose their lives each year as they search increasingly further into deeper water and caverns for this small fragile coral. Used exclusively in the tourist jewellery market, the brilliant red branches of this exquisite coral are a delight to see underwater and are thankfully protected in a number of areas.

Mother of Pearl Pinna nobilis

The Guinness Book of Records records the giant Mother of Pearl Pen Shell as the second largest shell in the world (after the Giant Clam). This species of mussel can exceed 1m (3ft) in height and is traditionally found in Posidonia seagrass meadows. Known to grow for over twenty years, they are collected by trophy hunters and also used in the jewellery trade.

Crowned or Long-spined Sea Urchin Centrostephanus longispinus

Sea urchins have long been regarded as a delicacy in the Mediterranean and the Long-spined Sea Urchin has been collected for generations. However, a virus has wiped out much of the Mediterranean population and although it is quite common in the eastern Mediterranean, it is considered quite rare elsewhere, but has been recorded as far west as Gibraltar.

Dusky Grouper Epinephelus marginatus

The local grouper population in the Mediterranean has been decimated by spear fishermen. Fairly sedentary in habit and often curious of nature, grouper have been an easy target for spear fishermen over many years. Malta and Gozo, Turkey, the Greek Islands, eastern Spain, Italy and southern France have all suffered from this. However, areas such as the Medas Islands in northern Spain, northern Sicily and the areas between southern Corsica and northern Sardinia are home to very healthy populations of large grouper.

Posidonia Sea Grass Posidonia oceanica

Posidonia is found off all Mediterranean coasts from depths of 0 to 40m (0–130ft). It is a flowering plant, and not an alga. It is home to myriad marine creatures and an important fish hatchery, the plants actually anchoring the seabed. Growing at only 3cm (1in) per year, to replace the vast meadows of Posidonia which have been lost owing to the construction of coastal marinas would take 3,000 years! Replanting programmes are ongoing in many coastal countries.

Seahorse Hippocampus spp.

The Seahorse is just one of many species affected by the loss of Posidonia meadows and coastal construction. The loss of the habitat is perhaps the largest problem facing these enigmatic and curious fish, but there are other factors which also threaten their existence, such as indiscriminate fishing methods and the Asian pharmaceutical interest, whereby over twenty million seahorses are sold throughout the world annually.

Monk Seal Monachus monachus

Near extinction, the Mediterranean Monk Seal has been hunted mercilessly by fishermen over the last fifty years as it was seen as the singular largest threat to fishermen’s livelihood. Now severely restricted to a few small desert islands between Greece and Turkey, early initiatives in marine conservation appear to be working. However, with a restricted gene pool, the future of Monk Seals in the Mediterranean is bleak. The seals are also found in Madeira and a few isolated pockets of Morocco.

The Seahorse Hippocampus ramulosus is an endangered species, threatened by severe habitat loss.

Classification and Nomenclature

You will note that in this guidebook to the Mediterranean, many species names of marine life are given in both the common and Latin scientific name. Common names are given wherever possible, but with so many different countries around the borders of this sea, it is almost impossible to find a common name to suit all species. The scientific name describing the nomenclature of a particular animal is very important. When diving in various parts of the world, or even in the same region, you may come across several different names for the same creature. This can be confusing. Scientists prefer that when identifying or describing a particular animal, you use its scientific or specific name.

The correct naming of a species is very important for your own log book records and is essential to scientists and marine biologists studying flora and fauna now and in the future. The modern binomial system of nomenclature (i.e. genus and species) was developed by Linnaeus and dates from publication of his Systema Naturae in 1758 and subsequent years.

The scientific (Latin) name of an animal comprises the name of the genus to which it belongs, conveniently written in italics, or even underlined in some texts. This first name always has a capital letter and is followed by the specific or trivial name which is always spelt with a small letter, e.g. Posidonia oceanica (Neptune Grass). Once you get into the habit of using the proper scientific names you soon find how easy it is and how good it is for describing species in a common language used by enthusiasts.

Making Choices in Marine Conservation

When booking a holiday, research the area first and use only diving schools which are involved with their local marine parks and conservation initiatives.

Contact the appropriate conservation agencies to see if there is specific information on the areas that you may want to dive.

Ask your tour operator if they have an environmental policy and if they contribute to marine conservation societies.

Make sure that dive shops and operators explain their specific conservation policies before the dive or snorkel, as this will undoubtedly help your awareness and lessen your impact on the marine environment.

Follow the example of other conservationists and use biodegradable shampoos, dispose of your litter appropriately, use fresh water sparingly and try and further the conservation message.

Souvenirs

Collection of marine souvenirs is prohibited in most areas, so respect all local and international laws.

The collection of empty beach shells may well seem innocent, but these shells may be used by small blennies as nesting sites, or by hermit crabs looking for a new home. Be careful in your selection.

All corals and turtle products are protected under CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) and can be bought and sold only under licence.

Red Hermit Crab Dardanus calidus at home.

Never buy marine curios, as they will probably be from another area of the world which is under even more threat and where the fishing methods used in the collection of the species may well be suspect.

Sea Stingers of the Mediterranean

As far back as written records began, man has recorded the plight of his fellow creature being stung by one or another of the denizens of the deep. Aristotle first accurately described the stinging properties of stingrays and jellyfish in 350 BC. The Greek poet Oppian wrote how the barb of a stingray could kill a tree and, on that same note, Pliny, describing the stingray, wrote in the Historia Naturalis: ‘So venomous it is, that if it be struchen into the root of a tree, it killeth it: it is able to pierce a good cuirace or jacke of buffe, or such like, as if it were an arrow shot or a dart launched: but besides the force and power that it hath that way answerable to iron and steele, the wound that it maketh, it is therewith poisoned.’

Venom in most cases is used purely for defensive purposes. As a working underwater photographer specializing in marine life studies, you quickly learn that if the creature that you are approaching does not swim away, then it must have some other form of defence. These creatures include small coelenterates and jellyfish, the tiny bristles of fire worms, and the pointed, modified tips of fins from various fish, anemones, sea urchins, starfish, molluscs and corals. In general terms, stinging mechanisms found around the mouth parts are for offensive reasons and stinging parts found along the back and tail are defensive in origin.

Different creatures have different types of toxins and potency. Most cause localized effects such as numbness, irritation or paralysis; others kill nerves, blood cells or attack muscles and affect internal organs. Most have a cumulative effect and cause several problems at the same time. In certain circumstances, these toxins can even cause death in humans. Around fifty deaths each year are attributed to sea stings of some nature.

As already mentioned, the most common stingers are jellyfish. These come in a vast army of different sizes and potency. All are members of the same superfamily which includes corals and anemones. These creatures are primarily offensive stingers. Their stinging mechanism is in the form of a hooked barb fired by a hydraulic coiled spring. These barbs are called nematocists and are held inside a trapdoor until they are released by touch or chemicals in the water. The barbs are hollow and filled with toxins which are released as soon as the stinger penetrates its victim. The primary aim is paralysis, before ingestion. Most jellyfish sting, but few are dangerous.

When seasonal changes are in their favour you can encounter the Portuguese Man-of-War Physalia physalis in tropical waters. These are highly toxic and continued exposure to the stinging cells may require hospital treatment. Whenever the conditions are favourable for Luminescent Jellyfish Pelagia noctiluca, there is always the chance of swimming beaches being affected. It is the almost invisible microorganisms in the water column which can cause skin irritation, so swimmers should wear protection such as a wet suit or the new style of Lycra skin suit. There are local remedies available for stings, but acetic acid (vinegar) is as good as anything. In cases of severe stinging, medical attention will be required. Closely related are the anemones, hydroids and corals, all of which have a surprisingly large number of harmful representatives. Most anemones will not do any harm to the much thicker skin on your fingers, but many can inflict quite painful ‘burns’ on the softer parts on the inside of your arms or legs. Species such as the Berried Anemone Alicia mirabilis has warty tubercles all over the stem of the anemone; each ‘berry’ is armed with lethal nematocists. The more common anemones use their barbs to hook and paralyse prey which swim inadvertently within their ‘sticky’ grasp.

Diver and Cassiopeia Jellyfish Cothyloriza tubercolata.

Hydroids such as the Sea Nettle Pennaria disticha have harmless-looking, feather-like plumes which can inflict a rather nasty sting on the softer areas of your skin if you brush up against them.

Even the most innocuous-looking sea creatures often have a hidden battery of stingers just waiting for something to rub against them. A few sponges have tiny calcium spicules which when rubbed against actually have a very similar effect to that of fibreglass rubbed against the softer parts of your skin. This can cause severe irritation, rashes and sores.

Fire worms Hermodice carunculata, although quite cute in appearance, should never be handled. These attractive, small worms have clumps of white hairs along their sides which display bristles when touched. These bristles easily break off in the skin causing a painful burning feeling and intense irritation. Although they are not deadly, stings will require treatment, principally with hot water and vinegar.

Perhaps one of the species we most associate with stings are members of the stonefish and scorpionfish families. There are no stonefish in the Mediterranean, but there are several species of scorpionfish, all of which are armed with a mild, toxic venom in the modified hollow spines found at the tips of the dorsal fins. These are not considered dangerous but care, as always, should be taken to avoid the spines on the top of the dorsal fin. Inadvertent stinging can be helped by placing the affected area into very hot water.

Other stingers in the fish world are the stingrays as previously mentioned. If you do encounter stingrays at close quarters, you must never attempt to grab hold of the tail or sit or stand on a stingray’s back, as the stinging mechanism is located in the tail. Any undue force on the creature may cause it to spring its tail forward in a reflex action, thus erecting the spine and causing serious damage. There are also species of electric ray found in the Mediterranean, which should be avoided. Weaverfish Trachinus draco like to inhabit shallow coastal areas and lie partly buried in the sand. They have a venomous spine on top of the dorsal fin and, although not lethal, it can cause extreme discomfort when stepped on. Similar species are stargazers Uranoscopus scaber, which have two venomous spines, one situated on each side behind the gill covers.

Not all stingers are large and obvious; quite a large number of molluscs also have stinging mechanisms. Nudibranchs, for instance, eat stinging hydroids and anemones and have the ability to store the stinging nematocists of their prey in their own tentacles. When attacked by predators, they are able to utilize the stored nematocists in defence.

Sea urchins and starfish are the last and most obvious group of sea creatures that seem to lie in wait for unwary and clumsy humans. Thankfully, with good buoyancy control and using cameras and lenses, which allow them to photograph these spiny creatures, divers are now able to avoid most brushes with these animals. The spines of a number of sea urchins can be poisonous. Even if not, they can puncture the skin – even through gloves – leaving painful wounds which can become septic. Although much rarer now in the Mediterranean (owing to an epidemic which almost wiped out the entire population) is the Long-spined Sea Urchin Centrostephanus longispinus. This urchin should be avoided as the spines are quite brittle and easily broken off in the flesh. Made of calcium, the spines in the flesh should dissolve after a few days. Deeply embedded spines may leave permanent scarring and patients may have to be treated for shock. Treatment includes rubbing the juice and pulp of the pawpaw, or even urine!

Most wounds to the unwary and uninitiated are caused by ignorance, as mentioned earlier. If the creature does not retreat from you, exhibits bright colours or moves into a defensive posture, then you can be fairly certain that it has a defence mechanism which can harm you. For those unfortunate enough to encounter some of the pelagic stingers of the sea, such as tiny microscopic jellyfish, all the advice that you have will never prepare you for the agony. It is recommended at all times never to scuba dive in just a swimming costume. You must always wear either a full wet suit or at the very least, one of the modern Lycra-type ‘skin suits’ for overall protection. If you are cautious and careful with your buoyancy, you should be able to gain a new understanding and appreciation on these much maligned ‘stingers of the sea’.

Diving Areas

Gibraltar

Starting from the extreme west and working along the northern shores of the Mediterranean, the northern ‘Pillar of Hercules’, or Gibraltar as it is more commonly known, is at the entrance to one of the world’s natural crossroads. It is here that the incoming current from the Atlantic Ocean mingles with the denser Mediterranean Sea creating a unique combination of flora and fauna. The ‘Rock’ as it is known, is home to several superb wrecks dating back to Napoleonic times, with the best of the wrecks being located off the breakwater and dating from the Second World War. These wrecks are home to a huge amount of marine life including sea fans, cucumbers, schools of anthias, nudi-branchs, octopus and cuttlefish.

Spain

Much of the southern Spanish coast is very similar in topography and species diversity to Gibraltar. As you travel north-east towards the French coast there are a number of marine protected areas, with good diving and excellent marine life to be found at Al Muñequa and Fuengirola. The most famous of all the protected areas is the Medas Islands off the coast near the resort of Estartit. These small rocky islands have been protected since the early 1980s and have absolutely huge concentrations of fish, including grouper, Sea Bass, bream, sardines and mullet. The mainland coast is carved with hundreds of gullies, caves and caverns, many of which travel several hundred metres underground and are home to slipper lobsters, colourful sponges, spiny lobsters and sea hares.

Gibraltar, at the entrance to the Mediterranean, is home to a huge diversity of marine species.

Medas Islands, Spain, are a protected marine preserve.

Balearics

The Spanish dependency islands of Formentera, Ibiza, Majorca and Menorca all have excellent diving, with many fine diving schools. The small island of Cabrera is undeveloped and is now a national park. The entire area has a similar feel to Malta and Gozo, with deep caverns, huge burrowing anemones, plenty of algal turf being grazed by wrasse, but few big fish. The best diving in Majorca is along the mountainous west coast between the ports of Polense and Andratx and there are huge schools of barracuda at the tip of Dragonara Island. Pont D’en Gil cavern in Menorca is popular with divers due to the ancient stalactite and stalagmite deposits underwater, testimony that this cave was once on dry land, before the Mediterranean was flooded.

France

There are a number of marine parks all along the southern French coast starting with the nature reserve of Cerbère-Banyuls just north of the Spanish border. Very similar to the geology of Estartit with many sea caves, the reserve is supported by the Arago Oceanographical Laboratory located at Banyuls-sur-mer to the north. The reserve is noted for its Dead Men’s Fingers and precious red corals. Near Toulon, the island of Porquerolles is administered by the French National Trust and has many interesting wrecks nearby. The Côte d’Azur has excellent diving around the offshore islands near Cannes, Cape Juan and Cape Antibes with some superb walls and interesting topography.

Monaco

Known as the home of the famous Oceanographical Institute supported by Jacques Yves Cousteau, Monaco still promotes itself as a leader in world conservation policies, yet it has lost 75 per cent of its natural coastline due to development. Monaco is now seen as being directly responsible for the introduction of Caulerpa taxifolia, which is endangering the entire Mediterranean.

Corsica

Cap de Scandola on the north-west coast of Corsica is set in the heart of a marine park which is dominated by huge tortured red volcanic rocks that plunge into the sea. Difficult to get to, the diving in the marine park is dominated by fields of red and yellow sea fans. Off the south-east coast can be found the Lavezzi Islands Nature Reserve which has been protected since 1970. The islands, of granite formation, are renowned for their friendly populations of large grouper.

Sardinia

Sardinia is under the protectorate of Italy and on the other side of the Strait of Bonifacio can be found the twin island nature park of Maddalena Island, also favoured by fish watchers. South of this small archipelago can be found the Gulf of Aranci at Capon Figari, where large concentrations of the Giant Fan Mussel Pinna nobilis can be found, some of which are almost 1m (3ft 3in) tall. Off the north-east coast can be found the spectacular cave and cavern formations of Nereo Cave at Capo Caccia. There are also a number of scenic wrecks to be explored along the east coast of the island.

Italy

Near Santa Margharitta at San Fruttuoso can be found the underwater sculpture of the ‘Christ of the Abyss’ placed by Guido Galletti in 1954. A copy of this statue can be found in the Pennekamp State Park in Florida. Commemorating the life of Cressi Sub founder Egidio Cressy, the statue is in the centre of a fine marine park which is home to thousands of damselfish. The island of Giannutri midway down the west coast of Italy has a couple of fine wrecks and nice sheltered bays. The ‘Nasim II’ and the ‘Anna Bianca’ are both in deep water, but are surrounded by thousands of anthias. The next group of islands to the south include the island of Ponza, where the wreck of the ‘LST349 MK.III’ lies. Sunk in 1943, the ship is an eerie reminder of the last World War. On nearby Ventotene Island can be found the wreck of the ‘Santa Lucia’, which also dates from 1943, but is a much better wreck for marine life.

Sicily

Bordering two major sea areas, Sicily forms part of the ancient land bridge which once split the Mediterranean. Not widely known for its conservation policies, Sicily has made more obvious steps in recent years with the tiny island of Ustica, just 36 miles off the coast of Sicily, facing Palermo. The tip of a subterranean volcano, the island is known for the huge amount of Sea Rose Sertella beaniana which can be found everywhere. Large colonies of Red Sea Fan are also evident. On the east coast, near Catania, can be found the marine reserve of Aci Trezza. Founded in 1992, the reserve is studied by the University of Catania, which has counted more than 300 species of algae within the park’s boundary. The islands are said to be the historical ‘Cyclops Islands’. Legend has it that the island is actually the colossal stones flung by the giant Polyphemus at Ulysses’ boat.

Canoeists exploring the Mediterranean coastline.

Malta, Gozo and Comino

Their location between Sicily and Libya is responsible for the huge diversity of marine life found around these islands. The country’s first marine reserve was declared in 2011 around Cirkewwa, close to the ferry terminal between Malta and Gozo. The Islands have superb clear water, fantastic caves and caverns and many historical shipwrecks including aircraft from WWII.

Croatia

Located bordering the north-eastern Adriatic, the islands off the coast of Croatia have been a sailor’s delight for years. Now divers are exploring beneath the waves, particularly off the island of Korcula and although the area has been overfished for many years, the invertebrate populations are high, with many different hermit crabs and nudibranchs. Large sponges, feather starfish and Red Sea Fans are symbolic of the diving off Korcula. Great White Sharks have been spotted near Istria, following the tuna migrations. There are several sites which have ancient amphora as well as wrecks from the Second World War including a fairly intact German submarine.

Greece

The Greek Islands are said to be the cradle of civilization, and there are countless numbers of historical monuments and ancient wrecks to testify to this fact. Sport diving was once restricted to only a few select sites of little interest, however over the last few years, more areas have become available for exploration and now divers are not only enjoying the wealth of marine life, they can also visit historic sites and underwater artefacts.

Crete

Separated from Turkey by the Sea of Crete, this ancient Mediterranean island has some interesting diving around its rocky shores. Best for diving is the western shore, which is less touristy. Nearby Chania has a large area of ancient amphora, now covered in an algal turf. There are large schools of bream and wrasse as well as interesting caves and caverns.

Cyprus

Diving is very popular in Cyprus, particularly around the Paphos region, with a number of diving schools having excellent reputations. The most famous wreck in Cyprus waters is that of the ‘Zenobia’ which sank in 1980. This 172m (570ft) wreck is a must for all divers visiting the island. The Akamas Peninsula is now earmarked as a marine park and the Akrotiri Fish Reserve near Limassol is very popular.

Turkey

South-eastern Turkey has some superb diving, especially those dives around the popular holiday resorts of Fethiye and Marmaris/Icmeler. Although it is not noted for its fish life, the huge sponges, octopus and other invertebrates more than compensate. The region is also dotted with ancient shipwrecks, sea caves and caverns, perfect for exploration. Turkish divers also know of a certain area where you can encounter Dusky Sharks Carcharinus obscurus.

Chromis or Damselfish Chromis chromis in Paradise Bay, Malta, enjoy shallow coastal waters all around the Mediterranean.

Mosaic of a fish at Pompeii, dated AD 79.

Syria

There is little knowledge of diving off the coast of Syria, but from accounts by Turkish divers the topography is very similar, with an interesting mix of fish coming up from the Red Sea. Diving here would have to be done by special permission and then only by boat.

Lebanon

A new Mediterranean country on the diving scene, there are a number of good wrecks in Lebanon, mainly dating from the civil war that shook the country in 1975. However, the country is also known to be home to small numbers of Ragged-toothed Sharks Odontaspis ferox.

Israel

There is some inshore diving to be found on the Israeli Mediterranean coast, but it is fairly restricted and generally on some not too ancient wrecks. These are all well colonized now by different algae and small anemones. Fish life is interesting, as there are a few migrants from the Red Sea to be found.

Egypt

The Egyptian coast was not known for its diving until some archaeology researchers found ancient remains off the harbour wall in Alexandria. These ancient sphinx, obelisks and statues are surrounded by damselfish and bream with a mix of fish and algae from the Red Sea. The area is quite unusual and will be open to mass market tourism shortly.

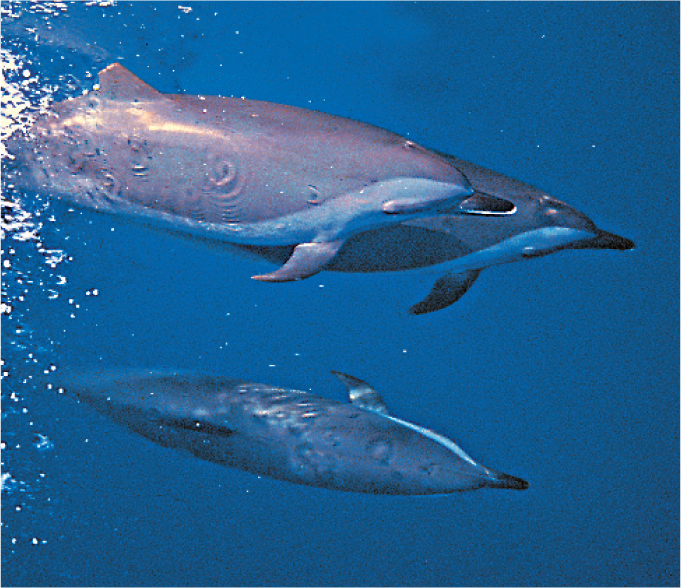

Common Dolphins riding a bow wave off the coast of Tunisia

Libya

The recent political troubles mean that the future is uncertain at present. However, prior to this the country was newly opened for tourists. Although diving was still in its infancy, the early reports stated that the offshore reefs and wrecks were pristine. Much of the larger inshore fish have gone, but there is a large invertebrate population.

Tunisia

The islands of Zembra and Zembretta were declared a national park in 1977 and are included in UNESCO’s list of Reserves of the Biosphere. The rare Giant Limpet is found here as well as local groups of dolphin. The National Institute of Marine Sciences and Technologies, which was founded in 1927, is involved in continuous research on the islands. Founded in 1980, the second reserve includes the islands of Galite and Galiton off the northern Tunisian coast and consists of one main island and five smaller ones. Of granite origin, unique in Tunisia, the islands are renowned for the Posidonia meadows, crayfish, large grouper and precious red corals. Once home to the Monk Seal, it is hoped that a few solitary individuals may make the islands home once more.

Algeria

Little is known about the Algerian coastline, but there are tales of excellent wrecks from various political conflicts, sunken cities and good marine life to be explored.

Morocco

Owing to constant political changes in the country, there is little scuba diving done. However, several operators from Gibraltar and southern Spain do occasionally cross the straits to dive some of the offshore reefs and islands. These are known for large grouper, lots of sea fans and a wide mix of Atlantic marine life.

KEY TO SYMBOLS

This key describes the symbols that appear at the head of each species description. The symbols give a quick guide to the habit, diet and habitat of each species.