CNIDARIANS

This is a large and fundamentally simple group of animals, widely distributed and seemingly totally diverse, in such a wide array of forms that they are not obviously related to one another. This family (phylum) formerly known as Coelenterata, includes true hard corals, soft corals, sea pens, sea fans, anemones, sea firs (hydroids), zoanthids and jellyfish. They come in two different forms, either as an attached polyp or a free-floating medusa.

All of the species are radically symmetrical without a right or left side. They have a single body cavity and a single terminal opening, usually surrounded by one or numerous rings of tentacles. It is these tentacles in various forms and adaptation which group the family together. Each tentacle is armed with stinging cells, cnidocytes, containing nematocysts. Nematocysts consist of small capsules which contain a smooth or barbed thread coiled inside. Used for defence or aggression and for catching prey, these stinging cells may also be found on other parts of the body. The toxins released when these ‘harpoons’ are fired may be powerful enough to cause a severe sting.

The typical shape is that of the anemone type with a single mouth, ringed with tentacles, with which the animal stings, stuns or captures its prey, to be drawn into the mouth and thence to the single, sac-like body cavity. Waste matter also exits through the mouth. Most cnidarians reproduce sexually, releasing floating larvae which inhabit other areas of the ocean. Some species split or bud to produce new polyps which remain attached thereby increasing the size of the colony, whilst others release free-floating eggs and sperm which are fertilized in open water, producing medusa which eventually settle onto the sea bed.

HYDROIDS

Commonly referred to as ‘Sea Firs’, hydroids usually live attached to rocky substrates and have a rather complicated life history. They are often mistaken for plants or algae. They form delicate fern or feather-like groups and can be quite profuse in certain areas. During sexual reproduction, they produce a free-swimming, tiny jellyfish called a hydromedusa. Although most hydroids have tiny polyps, they pack powerful stings and contact with them should be avoided.

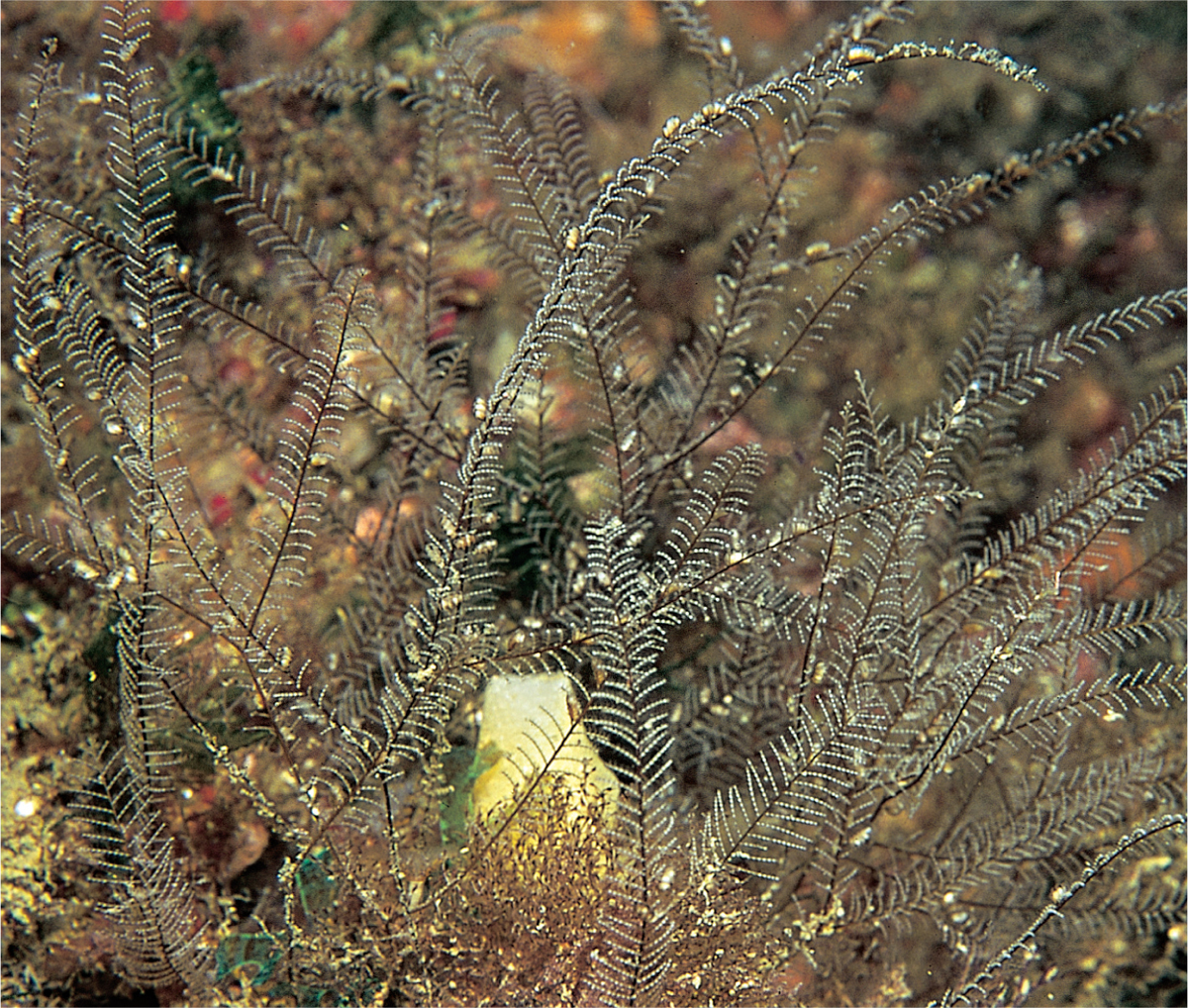

SEA FERN

Aglophenia spp.

Difficult to identify specifically, Aglophenia spp. are typical of the feather type of formation, with each ‘fern leaf’ reaching around 20cm (8in) in length. Unbranched, the side ‘shoots’ are opposite each other and form two vertical rows. The male gnophores tend to congregate along the stem, at no set intervals. Very common on the tops of rocks, it is often overlooked and can sting the softer parts of your skin.

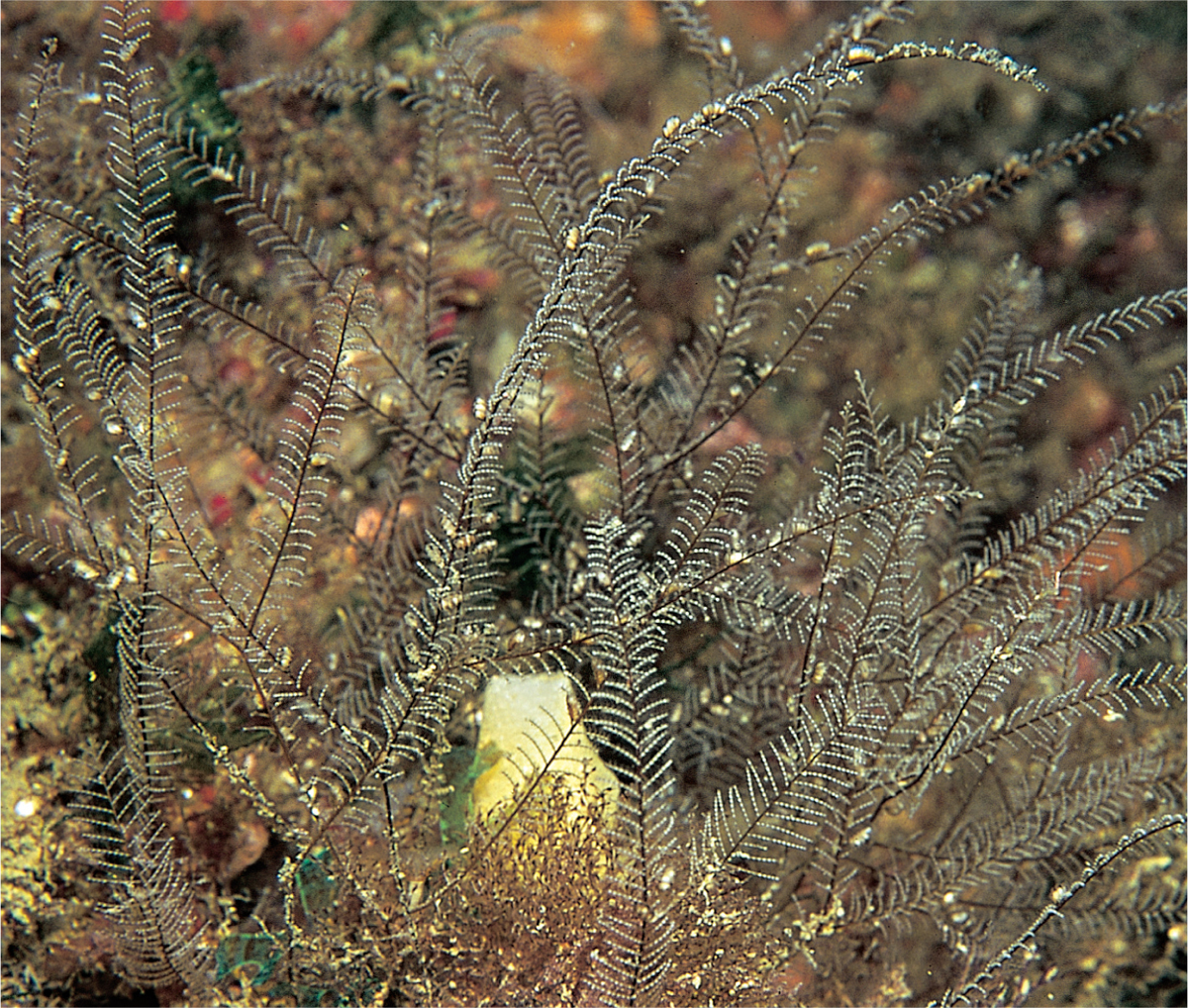

SEA FIR

Eudendrium rameum

This is a short, stubby hydroid with a small, quite thick basal stem, quickly branching out. Each polyp head is arranged in alternate sequence, crowned with 24 tentacles. The male gnophores will also be clustered around the polyps. Found in fairly shallow water of less than 15m (50ft), the hydroid thicket will rarely exceed 20cm (8in).

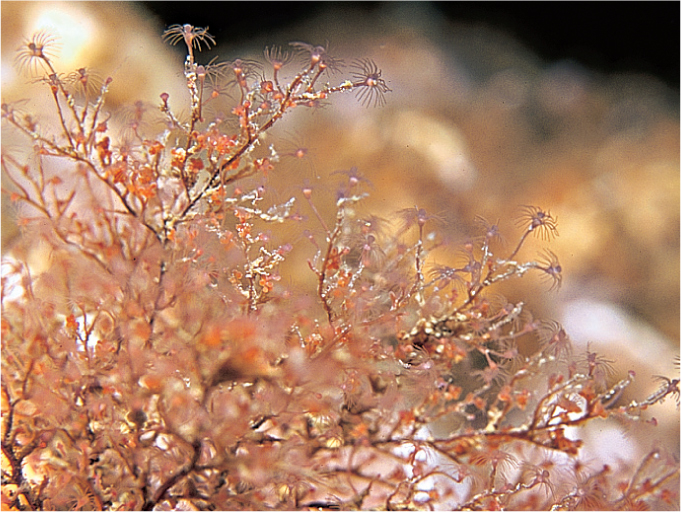

SEA FEATHER

Gymnangium montagui

These rather striking fronds of Gymnangium stand over 10cm (4in) tall and occur in depths of over 20m (66ft), typically on exposed cliff walls where there is plenty of aeration and passing planktonic particles. Golden brown in colour, colonies may contain several hundred fronds.

JELLYFISH

Jellyfish are the free-floating medusa where the polyp stage of the life cycle has either been totally suppressed or extremely reduced. The upper surface of the jellyfish is generally smooth to touch and is known as the aboral or exumbrellar portion. The subumbrellar portion is underneath and contains the various combinations of tentacles and mouth parts which are armed with a variety of stinging cells. Jellyfish are quite capable of directional movement by pulsing the outer bell, creating a staccato propulsion. More often than not they are at the mercy of tidal movements and bad weather and can be washed up on tourist beaches in large numbers.

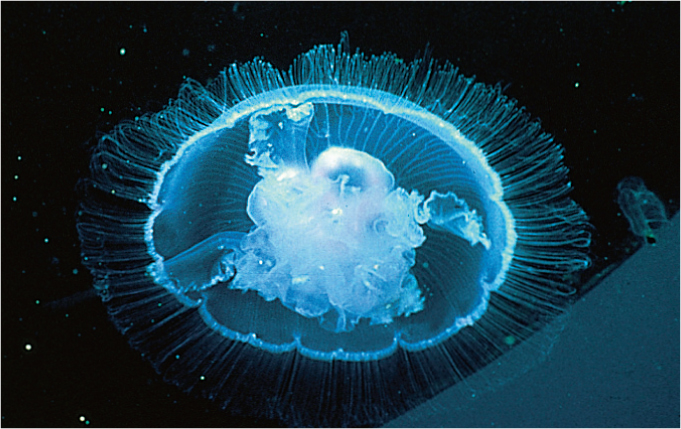

MOON JELLYFISH

Aurelia aurita

The Moon Jellyfish is one of the most common of all the jellyfish and occurs in all of our oceans and seas. Recognized by the four purplish or blue gonad rings found on the top of the bell, it can grow up to 40cm (1ft 4in) in diameter. The bell is surrounded by a ring of small tentacles and although not harmful to man, it preys on small fish and other planktonic larvae. This jellyfish uses the sun as a compass and forms breeding aggregations in late summer followed by extensive mutual migration into shallow coastal waters. The sedentary stage is found under rocky overhangs well aerated by tidal movement and releases young medusa into open waters in the spring.

CASSIOPEIA

Cothyloriza tubercolata

Occasionally called the ‘Fried Egg Jellyfish’, Cassiopeia comes into coastal waters in late summer driven by the need to spawn in shallow, well-lit waters. With a diameter of around 40cm (1ft 4in), this large, distinctive medusa has a creamy yellow bell top which is smaller than its tentacle ring. The tentacles are short and terminate in purple spots containing the stinging cells. Juvenile sand smelt and bogue are often found swimming within the ‘protective’ embrace of the tentacles.

LUMINESCENT JELLYFISH

Pelagia noctiluca

This oceanic jellyfish has a large, spotted bell of around 10cm (4in). These spots are actually warts armed with stinging cells. It has sixteen lobes, eight sense organs and eight marginal tentacles with four shorter frilled mouth tentacles under the bell. The marginal tentacles can extend over 1m (3ft 3in) long making them rather hazardous to swimmers during the summer months when this jellyfish can be quite prolific in inshore waters. There is no sessile stage in its reproduction, with the adult releasing juvenile medusae in the autumn.

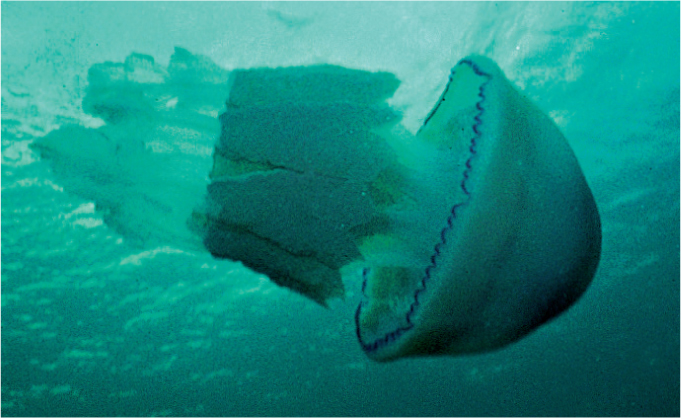

BELL JELLYFISH

Rhizostoma pulmo

The largest of the jellyfish encountered in the Mediterranean, the outer bell can be over 1m (3ft 3in) in diameter. Very solid in construction, it overwinters in deeper water and migrates from the Atlantic. The eight short clubbed tentacles are subdivided into numerous frilled mouths and employ a mucus coating to trap food particles.

SEA FANS or GORGONIANS

Sea fans are reasonably common throughout the Mediterranean and although there are few varieties, they are on the whole quite colourful, with the predominant species being Paramuricea clavata which can cover huge sections of cliff walls and wrecks. Owing to their sedentary nature, they prefer areas of moving water. Sea fans are characterized by an erect colony of individuals which form an intricate web of dividing branches with extended polyps. They are aligned along a single plane across the prevailing current with which to snare prey as it passes in the tidal stream.

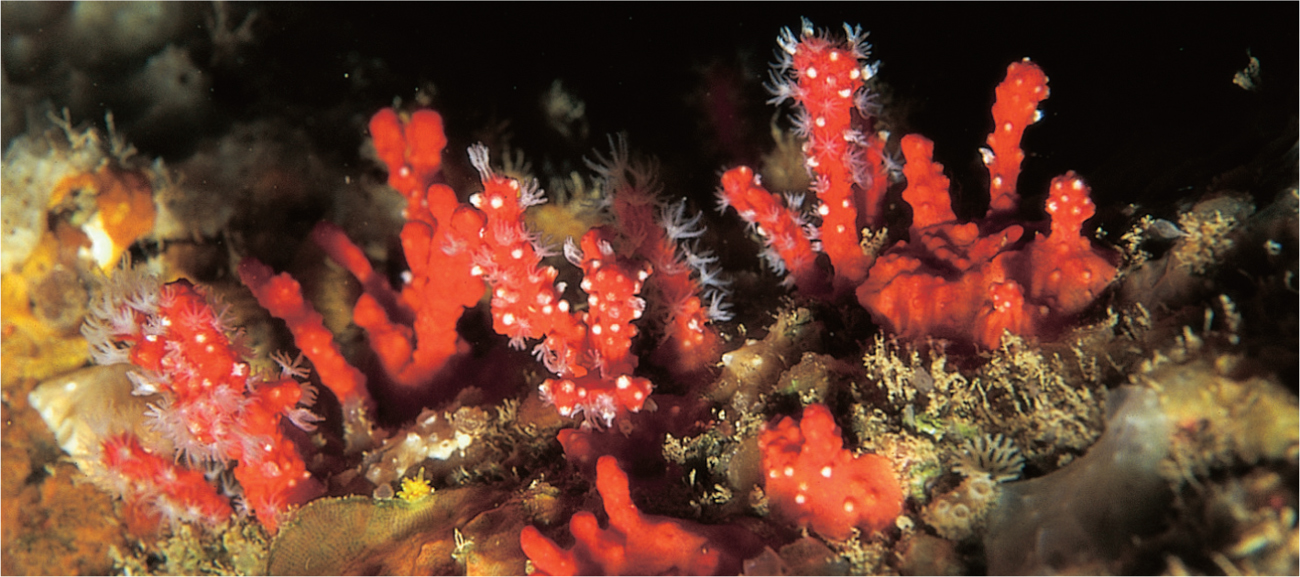

PRECIOUS or RED CORAL

Corallium rubrum

Extensively collected and highly valued since classical times, Red Coral, although not growing in the traditional fan shape, is directly related to other gorgonians. The larger specimens have been intensively harvested over the years and are now only found in very deep water or in undiscovered caves. Each year, commercial coral divers are still killed or paralysed by the crippling ‘bends’ in their illegal search for greater and better-formed branches. Recognized as a protected species, the small, knobbly, three-dimensional branching colonies prefer deep caverns and other areas of very low light, including deep water. Most of the larger colonies have now all been fished out, leaving only tantalizing remnants of smaller colonies for us to still admire. The classic red colour is instantly recognizable with white widely spaced polyps. This fragile coral is variable in size depending on its location. In general diving areas in caves and caverns, it only grows to 3cm (1¼in); larger fans of this highly prized coral may be found in deeper waters.

YELLOW SEA FAN

Eunicella cavolinii

Very similar to Eunicella verrucosa except that the polyps are arranged in whorls at the tips of each branch. It enjoys vertical cliff walls where the fans, growing to around 40cm (1ft 4in) lie across the current to collect food particles. Found in shallow depths from 10 to 30m (33–100ft).

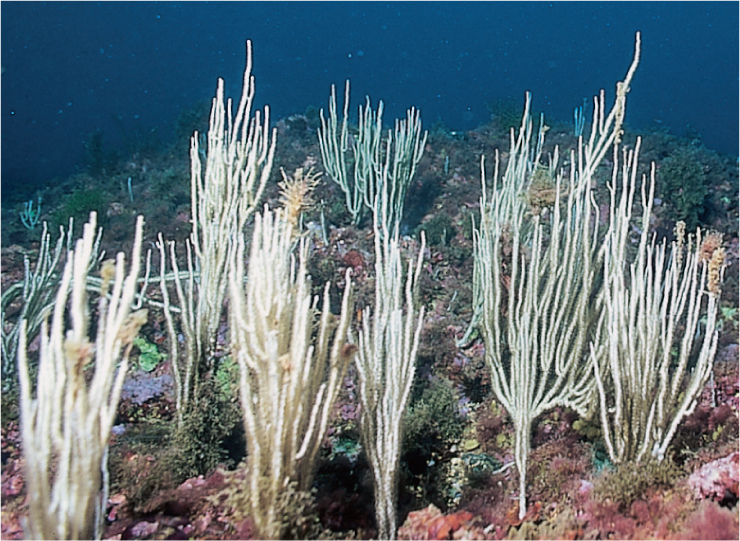

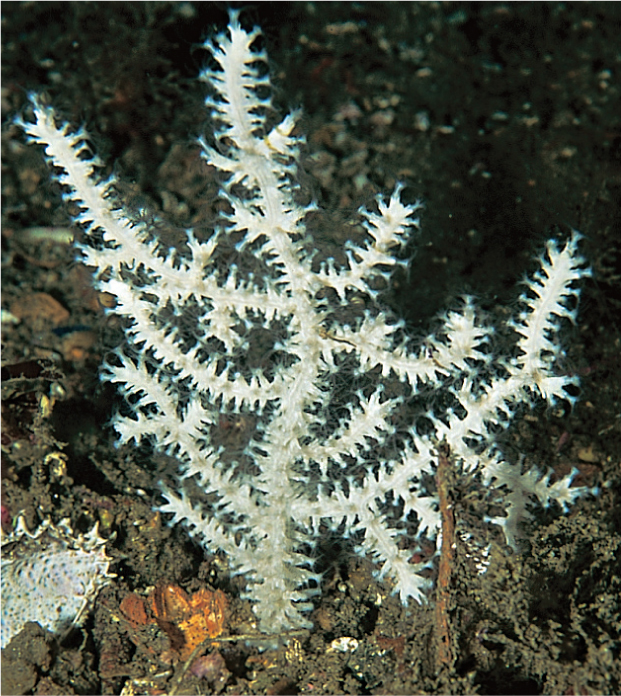

WHITE SEA FAN

Eunicella singularis

The most common of the sea fans and ranging throughout the Mediterranean, the White Sea Fan lives on rocks or wrecks alike in depths of over 12m (40ft) and can cover large areas. From a common stem, the branches are elongated and generally stretch upwards to a height of 30cm (12in). It has a microscopic, symbiotic algae, which may give it a slightly green coloration. The small polyps are darker than the body.

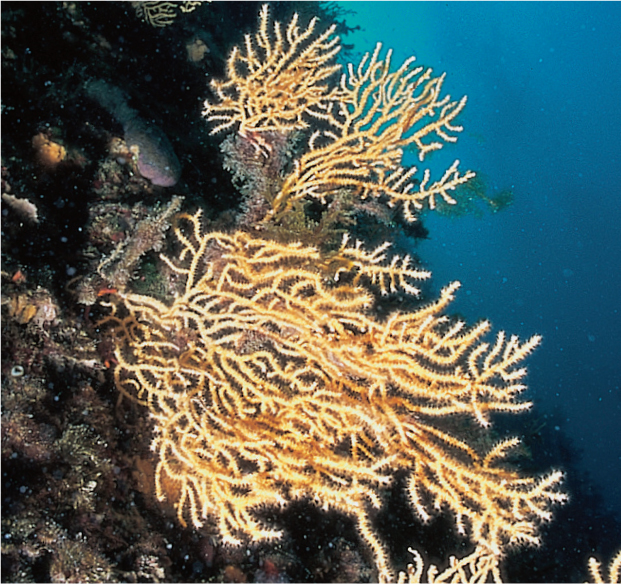

WARTY SEA FAN

Eunicella verrucosa

This species is closely related to E. singularis, but is more richly branched, forming a wider fan shape, more like a true gorgonian, up to 30cm (12in). Protruding out from the branches, the polyps are white in colour and have no pattern, arranged in double rows towards the tips. This distinctive species is found as far north as the British Isles and is always a delight for divers to find there, as the thought of exotic corals in British waters is something of a novelty! Preferring more sheltered locations and deeper water than Eunicella singularis, this species is preyed upon by various nudibranchs.

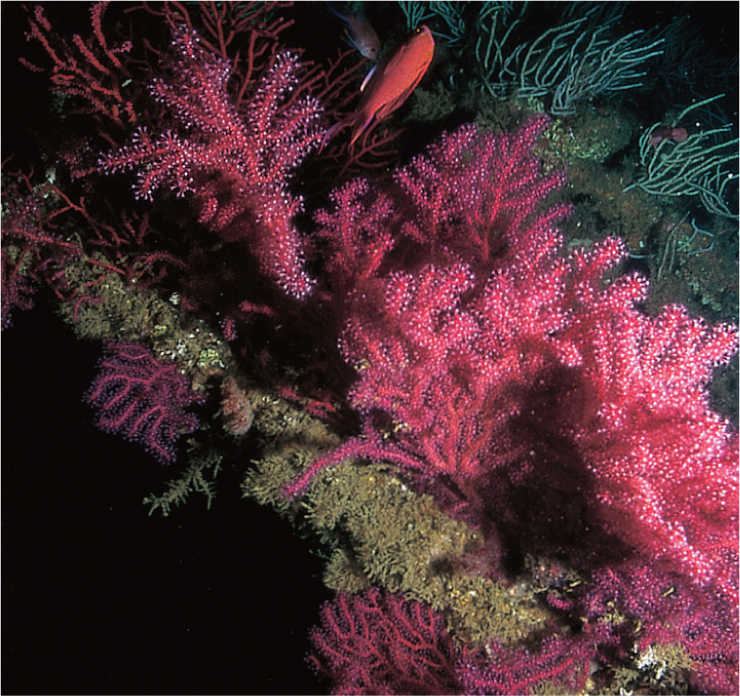

RED SEA FAN

Paramuricea clavata

The most common and colourful of all the Mediterranean sea fans, the Red Sea Fan adorns most vertical cliff faces in the central and western areas, growing up to 60cm (2ft). Depending on certain conditions, the fans will vary in colour from white through yellow to ruby red and purple, quite often on the same animal. Several areas are particularly well known for their extensive colonies, such as the Medas Islands, the Straits of Bonifacio between Corsica and Sardinia, the islands of Elba and Ustica, and the wrecks of Gibraltar. The Red Sea Fan particularly likes clear, clean water on offshore rocky seamounts where it gets the most benefit from coastal currents. The fans are also an important habitat for several species of nudibranch and mollusc, and even cat sharks lay their egg cases on them where the aerated water is most beneficial to the developing embryo (see here).

GORGONIAN

Lophogorgia sarmentosa

Rosy red in colour, this sea fan has widely spaced branches which spread out from a common root stalk. The polyps are slightly lighter than the body colour and they create an effective net to capture food particles. Generally found in depths greater than 20m (66ft), this sea fan is quite rare in most areas.

OCTOCORALLIA

This family includes the soft corals, sea fans and sea pens. The medusoid stage in octocorallians has been suppressed and all of the animals represented in the Mediterranean are in fact colonies consisting of loosely connected polyps. The sea fans are more complex and create a hard skeleton underlying the polyps. Whilst this makes a perfect shape for netting passing food particles, sea fans are also prone to colonization by other species and can become completely overgrown. Sea pens tend to hide under soft sediments during the day and extend their soft bodies by infusing water and stretching upwards to feed at night.

SEA FINGERS

Alcyonium acaule

These hand-shaped colonies with stubby finger-like projections up to 12cm (5in) long are always rosy red in colour, with polyps which are tinged the same colour or even light yellow. This species can have quite a wide-spreading base attached to hard substrate. Closely related to all other Dead Men’s Fingers, these compacted colonies can be found in depths of more than 20m (66ft), quite often on shipwrecks.

DEAD MEN’S FINGERS

Alcyonium palmatum

Compared with the previous one, this species forms more slender, upright branching colonies up to 12cm (5in) tall, connected to a hard substrata by a more slender columnar base. The body colour can vary from pale yellow through orange to red, but the polyps are always white and more spread out than on other related species. All of the Alcyonium species are characterized by their stubby, digiform-like ramifications, always cylindrical in shape and stretching from a common base, which has little or no polyps. They are heavily preyed upon by a number of different nudibranch species. The polyps tend only to extend for feeding during strong surge, current or at night; at other times, the ‘fingers’ resemble more the form of a jointed red sponge.

FALSE RED CORAL

Parerythropodium coralloides

This particular form of the family tends to form thin encrusting sheets which colonize gorgonian sea fans. Spreading up from the base, these colonial octocorallians have a ruby-red body and lighter, widely spaced, raised polyps. They are known to form small clumps on rocks and may even overgrow shells, but they are more commonly seen on Eunicella sea fans where the colour change is more striking.

ROUND SEA PEN

Veretillum cynomorium

Particularly common in the western Mediterranean around Morocco, Gibraltar and the Costa Del Sol, this species prefers soft, fine sand or a muddy substrate where its long foot can stay buried. If the habitat is threatened, perhaps in a violent storm or through pollution, it has the ability to release the water from its column, pull free of the seabed and gently roll off in the current until it finds another suitable habitat. Growing to over 20cm (8in) in length, the Round Sea Pen expands and retracts its cylindrical body by pumping water through its cavity. Usually only seen at night, this is one of the larger sea pens to be found in the Mediterranean. Pale orange or yellow in colour, the polyps are varied in colour from white to brown and can extend over 2cm (¾in).

COMMON SEA PEN

Virgularia mirabilis

Little seen, this small species up to 17cm (7in) in height prefers deeper waters with some current to spread its distinctly grouped polyps. Found in clusters of three to eight and located in two rows, the polyp and column are able to turn towards the prevailing current and create a net with which to catch food particles.

HEXACORALLIA

This subdivision of the zoanthids is the largest family group and includes the anemones, zoanthids and corals. The name indicates that the polyp tentacles are arranged in groups of six rather than eight (octocorals such as Dead Men’s Fingers or sea fans). Most anemones are solitary and attached to a hard substrate by means of a basal sucker. Others burrow into soft sand or mud creating a protective tube into which they can withdraw. Some species enjoy living in close proximity due to the very nature of their reproduction, such as the Snakelocks Anemone which multiplies by fission, creating two complete adults. Others produce live young. Some use pedal laceration where part of the column or base is detached and which grows into a new polyp. All anemones are carnivorous, trapping unwary small fish or invertebrates within the sticky grasp of their tentacles. Many creatures are also seemingly immune from the stinging cells and live within the range of the tentacles for protection from other predators. Two species of Hermit Crab are even more closely associated with anemones, playing direct host for additional protection.

ACTINOTHOE

Actinothoe sphryodeta

Most common around Gibraltar, Morocco and the eastern coast of southern Spain, this is a communal species found readily on shipwrecks and rocky surfaces. It has over a hundred tentacles, which are always white, with the disc ranging in colour from a fluorescent green to orange or brown and 4cm (1½in) across. It is able to fire sticky threads from the tentacles as a means of catching prey.

CLOAK ANEMONE

Adamsia carciniapados

A truly adaptive species, the Cloak Anemone wraps itself around the shell inhabited by the hermit crab Pagarus prideaux. The column of the anemone is pale fawn with garish magenta spots and the oral disc contains over five hundred small tentacles. The disc is usually found on the bottom of the crab’s shell and enjoys the hermit crab’s messy leftovers. Its size depends on the shell it covers. When threatened it secretes long, sticky, magenta threads.

TRUMPET ANEMONE

Aiptasia mutabilis

Living in holes or small crevices, the slender column (up to 17cm [7in] long) of this anemone is rarely seen. The column flares out widely and has about a hundred long, almost transparent tentacles. The tentacles do not retract readily; rather, they have additional protection in the form of a coiled sticky thread which shoots out from the tentacle tip if threatened. The anemone has a bluish tint due to the presence of zooxanthellae.

BERRIED ANEMONE

Alicia mirabilis

Sometimes referred to as the ‘Wonder Anemone’ owing to its amazing stretching ability, Alicia is better recognized by the numerous small berries which cover its body. These berries or tubercles are armed with stinging cells and can be quite harmful to human touch. During the day, it closes up and becomes a small inconspicuous lump only 10–15cm (4–6in) tall with its tentacles retracted. At night it can stretch over 1m (3ft 3in) and its long tentacles trap prey in the current.

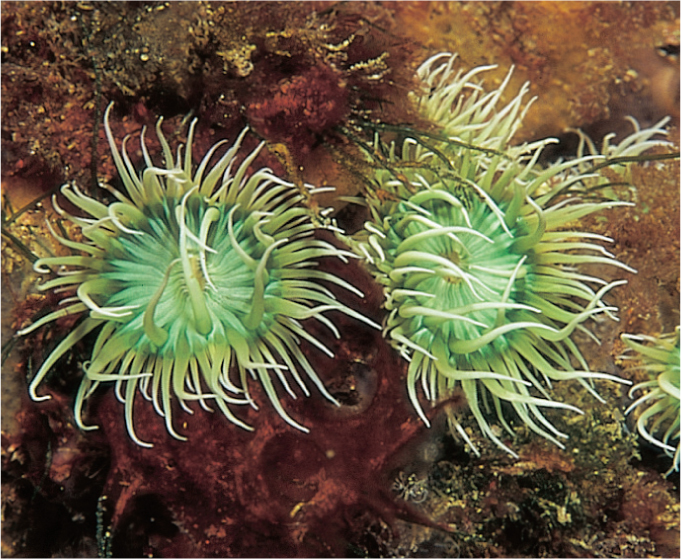

SNAKELOCKS ANEMONE

Anemonia sulcata

One of the most common of the Mediterranean anemones, the Snakelocks Anemone is instantly recognizable by its ‘gorgon-like’ head of around two hundred tentacles, which are unable to be retracted as they are simply so numerous and so much larger than the body cavity. Generally grey or green in colour with purple-tipped tentacles, it is found on the lower shore where it is associated with a number of small crabs and gobies. It is up to 19cm (7½in) across.

HERMIT ANEMONE

Calliactis parasitica

Also living in association with a hermit crab, this large anemone, 5cm (2in) across, has quite a stiff column, cream in colour with vertical brown stripes. The oral parts are ringed by over seven hundred slender tentacles and the body is able to fire sticky threads or acontia when threatened. The hermit crab’s shell can be found with large numbers of these heavy anemones, making it rather difficult for the crab to manoeuvre – but it is well protected!

DAISY ANEMONE

Cereus pedunculatus

Not as common as other anemones, this species lives happily amongst small stones, rocks or even a rough gravel seabed. In overall shades of brown, this anemone is tall and trumpet shaped with a wide oral disc surrounded by between five hundred and a thousand short tentacles. The column has some indistinct suckers to which it can attach bits of debris to create additional camouflage. It is 5cm (2in) across.

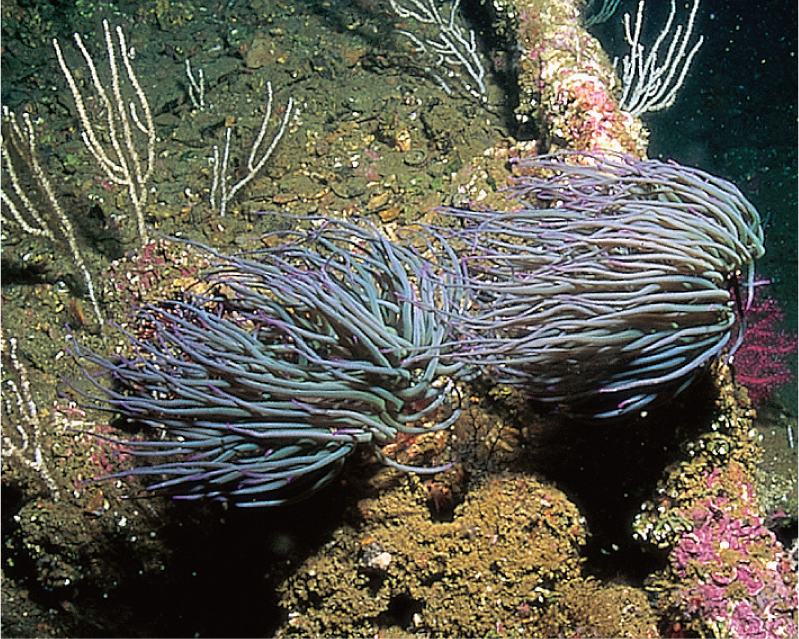

FIREWORKS ANEMONE

Cerianthus membranaceus

One of the largest of the Mediterranean species, Cerianthus prefers deep sheltered water or inside caverns, well away from strong sunlight. Secreting a parchment-like tube in the soft mud or sandy seabed, this anemone is distinguishable from other species by having two different types of tentacles. Inside the mouth are large numbers of small feeding tentacles, surrounded by very long, outer catching tentacles, which form an ‘exploding firework’ effect reaching over 1.50m (5ft). Sensitive to both pressure and light, this anemone is quite difficult to photograph as it is extremely retractile, being able to withdraw its tentacles in a split second.

GOLDEN ANEMONE

Condylactis aurantiaca

This large anemone lives in the soft sand in deep water, usually over 25m (80ft). The column is deep down in the sand, normally attached to a small stone. The oral disc is ringed with ninety-six fat tentacles with an overall diameter of around 20cm (8in). The anemone is sometimes mistaken for the Snakelocks Anemone due to the coloration of its tentacles, which are usually greenish in colour and tipped in purple. Large numbers of these are found around the wreck of the Rozi in Malta.

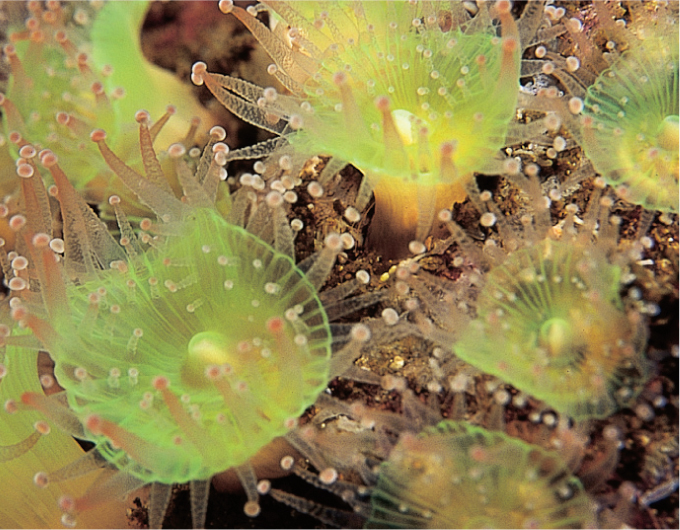

JEWEL ANEMONE

Corynactis viridis

Not usually associated with the Mediterranean, this tiny anemone is surprisingly common on offshore sea mounts and vertical deep walls where it enjoys low sunlight and nutrient-rich water. With the polyps reaching only a maximum size of 10mm (½in), it is invariably still easy to spot owing to its iridescent bright colour. The short tentacles are characterized by having a knobbly tip. Able to reproduce asexually, many individuals of the same colour form are found together, often forming large sheets of colour.

DAHLIA ANEMONE

Cribinopsis crassa

Very similar to the Urticina species found in British waters, Cribinopsis is quite rare and only found on its own. Preferring a rocky crevice or hole in which to hide its body column, the short stubby tentacles are very retractile. Coming in various shades of blue and green owing to the presence of symbiotic zooxanthellae, it grows to around 12cm (4¾in) in diameter. This anemone is commonly associated with its symbiotic partner, the Amethyst Shrimp Periclimenes amethysteus.

ZOANTHIDS

Zoanthids are short colonial animals, very similar to anemones and other corals. The species have no skeleton and spread by means of an extending or creeping stolon. The single mouth of each polyp is ringed by two rows of tentacles containing a symbiotic alga known as zooxanthellae.

GOLDEN ZOANTHID

Parazoanthus axinellae

These are brilliant yellow- to orange-coloured polyps, which can grow as high as 2cm (¾in) and have twenty-four to thirty-six tentacles in two cycles. Preferring shaded areas, they are found under overhangs, at the entrances to caverns and are known to colonize many other types of more sedentary forms of marine life such as sea squirts, pen shells and even sea fans.

CORALS

The corals found in the Mediterranean are of the solitary polyp variety and although one may find large extensive colonies, the reef-building corals more commonly associated with tropical waters are not found owing to the lower temperature of the water. Unlike the anemones, corals are supported by a calcified skeleton, which can form large colonies.

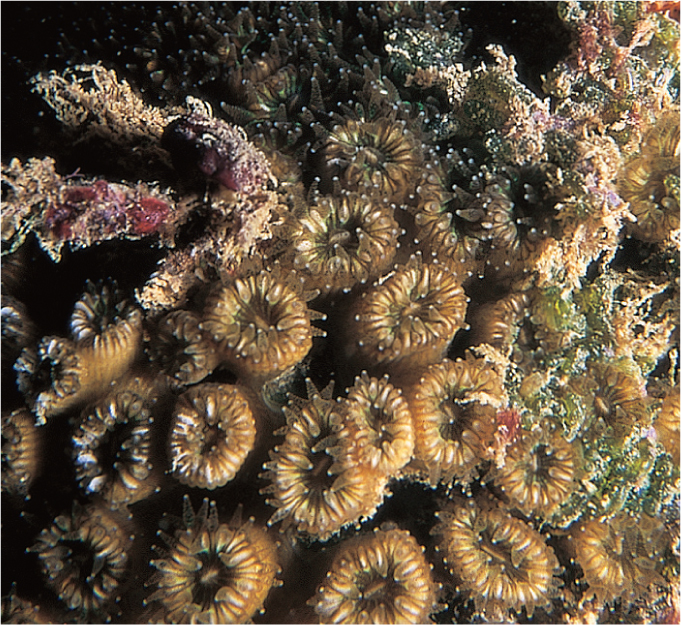

STAR CORAL

Astroides calycularis

This brilliantly golden-coloured coral forms large sheets, which overgrow rocky surfaces. Reaching over 2cm (¾in) when fully extended, it forms large colonies. The calcified skeletons are connected by a common coenosteum with the mantle or bodies of the animals seemingly connected because they are packed so tightly together.

CUP CORAL

Caryophyllia smithii

One of the few coral polyps that inhabits British waters, the cup coral is particularly common in the western Mediterranean. This familiar species is recognized by its knobbly ended tentacles spreading out from a deeply grooved calcified disc approximately 1.5cm (½in) in diameter. As in all cup coral species, the tentacles are able to be retracted, allowing the calcified exterior to offer full protection to the animal.

MAT CORAL

Cladocora caespitosa

A migrant from the Atlantic, Cladocora is one of the few cup coral species that forms dense mats of individuals. Similar in structure to the reef-building corals of more tropical waters, this species has calcified ‘heads’ from 5 to 10mm (¼–½in) in diameter. Brownish-green in colour, the colonies can grow over 1m (3ft 3in) across.

YELLOW CUP CORAL

Leptosammia pruvoti

This solitary coral polyp is distinguishable by its brilliant, almost fluorescent, yellow colour. Quite tall, the stem or corallum can be 2cm (¾in) high. It prefers cave or cavern conditions as it is particularly light sensitive.

DARK SOLITARY CORAL

Phyllangia mouchezii

More notably found in the western Mediterranean, this is another species which has migrated into the Alboran Sea from the Atlantic. Solitary in disposition, it has a pronounced brown calcified corallum reaching over 2cm (¾in). The tentacles are almost transparent and knobbly.