INTRODUCTION TO THE 1996 EDITION

![]()

The Taoteching is at heart a simple book. Written at the end of the sixth century B.C. by a man called Lao-tzu, it’s a vision of what our lives would be like if we were more like the dark, new moon.

Lao-tzu teaches us that the dark can always become light and contains within itself the potential for growth and long life, while the light can only become dark and brings with it decay and early death. Lao-tzu chose long life. Thus, he chose the dark.

The word that Lao-tzu chose to represent this vision was Tao, ![]() But tao means “road” or “way” and doesn’t appear to have anything to do with darkness. The character is made up of two graphs:

But tao means “road” or “way” and doesn’t appear to have anything to do with darkness. The character is made up of two graphs: ![]() (head) and

(head) and ![]() (go). To make sense of how the character came to be constructed, early Chinese philologists concluded that “head” must mean the start of something and that the two graphs together show someone starting on a trip. But I find the explanation of a modern scholar of comparative religion, Tu Er-wei, more convincing. Professor Tu says the “head” in the character tao is the face of the moon. And the meaning of “road” comes from watching this disembodied face as it moves across the sky.

(go). To make sense of how the character came to be constructed, early Chinese philologists concluded that “head” must mean the start of something and that the two graphs together show someone starting on a trip. But I find the explanation of a modern scholar of comparative religion, Tu Er-wei, more convincing. Professor Tu says the “head” in the character tao is the face of the moon. And the meaning of “road” comes from watching this disembodied face as it moves across the sky.

Professor Tu also notes that tao shares a common linguistic heritage with words that mean “moon” or “new moon” in other cultures: Tibetans call the moon da-ua; the Miao, who now live in southwest China but who lived in the same state as Lao-tzu when he was alive, call it tao-tie; the ancient Egyptians called it thoth. Tu Er-wei could have added dar-sha, which means “new moon” in Sanskrit.

However, the heart of Tu’s thesis is not linguistic but textual, and based on references within the Taoteching. Lao-tzu says the Tao is between Heaven and Earth, it’s Heaven’s Gate, it’s empty but inexhaustible, it doesn’t die, it waxes and wanes, it’s distant and dark, it doesn’t try to be full, it’s the light that doesn’t blind, it has thirty spokes and two thirteen-day (visible) phases, it can be strung like a bow or expand and contract like a bellows, it moves the other way (relative to the sun, it appears/rises later and later), it’s the great image, the hidden immortal, the crescent soul, the dark union, the dark womb, the dark beyond dark. If this isn’t the moon, what is it?

Tu Er-wei has, I think, uncovered a deep and primitive layer of the Taoteching that has escaped the attention of other scholars. Of course, we cannot say for certain that Lao-tzu was consciously aware of the Tao’s association with the moon. But we have his images, and they are too often lunar to dismiss as accidental.

In associating the Tao with the moon, Lao-tzu was not alone. The symbol Taoists have used since ancient times to represent the Tao, ![]() , shows the two conjoined phases of the moon. And how could they ignore such an obvious connection between its cycle of change and our own? Every month we watch the moon grow from nothing to a luminous disk that scatters the stars and pulls the tides within us all. The oceans feel it. The earth feels it. Plants and animals feel it. Humans also feel it, though it is women who seem to be most aware of it. In the Huangti Neiching, or Yellow Emperor’s Internal Book of Medicine, Ch’i Po explained this to the Yellow Emperor, “When the moon begins to grow, blood and breath begin to surge. When the moon is completely full, blood and breath are at their fullest, tendons and muscles are at their strongest. When the moon is completely empty, tendons and muscles are at their weakest” (8.26).

, shows the two conjoined phases of the moon. And how could they ignore such an obvious connection between its cycle of change and our own? Every month we watch the moon grow from nothing to a luminous disk that scatters the stars and pulls the tides within us all. The oceans feel it. The earth feels it. Plants and animals feel it. Humans also feel it, though it is women who seem to be most aware of it. In the Huangti Neiching, or Yellow Emperor’s Internal Book of Medicine, Ch’i Po explained this to the Yellow Emperor, “When the moon begins to grow, blood and breath begin to surge. When the moon is completely full, blood and breath are at their fullest, tendons and muscles are at their strongest. When the moon is completely empty, tendons and muscles are at their weakest” (8.26).

The advance of civilization has separated us from this easy lunar awareness. We call people affected by the moon “lunatics,” making clear our disdain for its power. Lao-tzu redirects our vision to this ancient mirror. But instead of pointing to its light, he points to its darkness. Every month the moon effortlessly shows us that something comes from nothing. Lao-tzu asks us to emulate this aspect of the moon — not the full moon, which is destined to wane, but the new moon, which holds the promise of rebirth. And while he has us gazing at the moon’s dark mirror, he asks why we don’t live longer than we do. After all, don’t we share the same nature as the moon? And isn’t the moon immortal?

Scholars tend to ignore Lao-tzu’s emphasis on darkness and immortality, for it takes the book beyond the reach of academic analysis. For scholars, darkness is just a more poetic way of describing the mysterious. And immortality is a euphemism for long life. Over the years, they have distilled what they call Lao-tzu’s “Taoist philosophy” from the later developments of “Taoist religion.” They call the Taoteching a treatise on political or military strategy, or they see it as primitive scientific naturalism or utopianism — or just a bunch of sayings.

But trying to force the Taoteching into the categories of modern discourse not only distorts the Taoteching but also treats the traditions that later Taoists have associated with the text as irrelevant and misguided. Meanwhile, the Taoteching continues to inspire millions of Chinese as a spiritual text. And I have tried to present it in that dark light. The words of philosophers fail here. If words are of any use at all, they are the words of the poet. For poetry has the ability to point us toward the truth then stand aside, while prose stands in the doorway relating all the wonders on the other side but rarely lets us pass.

In this respect, the Taoteching is unique among the great literary works of the Chou dynasty (1122–221 B.C.). Aside from the anonymous poems and folksongs of the Shihching, or Book of Odes, we have no other poetic work from this early period of Chinese history. The wisdom of other sages was conveyed in prose. Although I haven’t attempted to reproduce Lao-tzu’s poetic devices (Hsu Yung-chang identifies twenty-eight different kinds of rhyme), I have tried to convey the poetic feel with which he strings together images for our breath and spirit, but not necessarily our minds. For the Taoteching is one long poem written in praise of something we cannot name, much less imagine.

Despite the elusiveness and namelessness of the Tao, Lao-tzu tells us we can approach it through Te. Te means “virtue,” in the sense of “moral character” as well as “power to act.” Yen Ling-feng says, “Virtue is the manifestation of the Way. The Way is what Virtue contains. Without the Way, Virtue would have no power. Without Virtue, the Way would have no appearance.” (See his commentary to verse 21.) Han Fei put it more simply: “Te is the Tao at work.” (See his commentary to verse 38.) Te is our entrance to the Tao. Te is what we cultivate. Lao-tzu’s Virtue, however, isn’t the virtue of adhering to a moral code but action that involves no moral code, no self, no other — no action.

These are the two poles around which the Taoteching turns: the Tao, the dark, the body, the essence, the Way; and Te, the light, the function, the spirit, Virtue. In terms of origin, the Tao comes first. In terms of practice, Te comes first. The dark gives the light a place to shine. The light allows us to see the dark. But too much light blinds. Lao-tzu saw people chasing the light and hastening their own destruction. He encouraged them to choose the dark instead of the light, less instead of more, weakness instead of strength, inaction instead of action. What could be simpler?

Lao-tzu’s preference for darkness extended to himself as well. For the past 2,500 years, the Chinese have revered the Taoteching as they have no other text, and yet they know next to nothing about its author. What they do know, or think they know, is contained in a brief biographical sketch included by Ssu-ma Ch’ien in a history of ancient China he completed around 100 B.C. Although we don’t know what Ssu-ma Ch’ien’s sources were, we do know he was considered the most widely traveled man of his age, and he went to great lengths to verify the information he used. Of late it has become popular, if not de rigueur, to debunk his account of Lao-tzu. But it remains the earliest one we have and is worth repeating.

According to Ssu-ma Ch’ien, Lao-tzu was a native of Huhsien prefecture in the state of Ch’u. Nowadays, Huhsien is called Luyi. If you are traveling in China, or simply want to find it on a map, look for the town of Shangchiu/Shangqiu on the train line that runs between the city of Chengchou/Zhengzhou, the capital of Honan province, and the Grand Canal town of Hsuchou/Xuzhou to the east. Luyi is about seventy kilometers to the south of Shangchiu. The series of shrines that mark the site of Lao-tzu’s former home is just east of town.

The region is known as the Huang-Huai Plain. As its name suggests, it is the result of the regular flooding of the Huangho, or Yellow River, to the north, and the Huaiho, or Huai River, to the south. The Chinese have been growing wheat and millet here since Neolithic times, and more recently cotton and tobacco. It remains one of the more productive agricultural areas of China, and it was a rich prize over which many ancient states fought.

Lao-tzu was born here in 604 B.C., or 571 B.C., depending on which account of later historians we accept. Ssu-ma Ch’ien doesn’t give us a date. But he does say that Huhsien was part of the great state of Ch’u. Officially, Huhsien belonged to the small state of Ch’en until 479 B.C., when Ch’u eliminated Ch’en as a state once and for all. Some scholars have interpreted this to mean that either Huhsien did not belong to Ch’u when Lao-tzu was alive or that he must have been born there after 479 B.C. But we need not accept either conclusion. Ssu-ma Ch’ien would have been aware that Ch’u controlled the fortunes of Ch’en as early as 598 B.C., when Ch’u briefly annexed Ch’en then changed its mind and allowed Ch’en to exist as a “neighbor state.”

Whether or not Huhsien was actually part of Ch’u is not important. What is important is that during the sixth century B.C., Ch’u controlled the region of which Huhsien was a part. This is significant not for verifying the accuracy of Ssu-ma Ch’ien’s account but for directing our attention to the cultural influence that Ch’u represented.

Ch’u was not like the other states in the Central Plains. Although the rulers of Ch’u traced their ancestry to a grandson of the Yellow Emperor, the patriarch of Chinese culture, they represented its shamanistic periphery. From their ancestral home in the Sungshan area, just south of the Yellow River, they moved, or were pushed, steadily southwest, eventually ending up in the Chingshan area, just north of the Yangtze. Over the centuries they mixed with other tribal groups, such as the Miao, and incorporated elements of their shamanistic cultures. The Ch’u rulers took for their surname the word hsiung, meaning “bear,” and they called themselves Man or Yi, which the Chinese in the central states interpreted to mean “barbarians.”

The influence of Ch’u’s culture on Lao-tzu is impossible to determine, but it does help us better understand the Taoteching, knowing that it was written by a man who was no stranger to shamanistic conceptions of the sacred world. Certainly as Taoism developed in later centuries, it remained heavily indebted to shamanism, and some scholars even see evidence of the Ch’u dialect in the Taoteching itself.

This, then, was the region where Lao-tzu grew up. But his name was not Lao-tzu, which means “Old Master.” Ssu-ma Ch’ien says his family name was Li, his personal name was Erh (meaning “ear,” hence, learned), and his posthumous name was Tan (meaning “long-eared,” hence, wise). In addition to providing us with a complete set of names, Ssu-ma Ch’ien also tells us that Lao-tzu, or Li Erh, served as keeper of the Chou dynasty’s Royal Archives.

Before continuing, I should note that some scholars reject Ssu-ma Ch’ien’s Li Erh or Li Tan and suggest instead a man named Lao Tan, who also served as keeper of the Royal Archives, but in the fourth century B.C. rather than the sixth. Some find this later date more acceptable in explaining Lao-tzu’s innovative literary style as well as in explaining why Chuang-tzu (369–286 B.C.) attributes passages of the Taoteching to Lao Tan but not Li Tan. For his part, Ssu-ma Ch’ien was certainly familiar with Chuang-tzu’s writings, and he was not unaware of the fourth-century historian Lao Tan. In fact, he admits that some people thought that Lao Tan was Lao-tzu. But Ssu-ma Ch’ien was not convinced that the two were the same man. After all, if Tan was Lao-tzu’s posthumous name, why shouldn’t Chuang-tzu and other later writers call him “Old Tan”? And why couldn’t there be two record keepers with the same personal name in the course of two centuries? If China’s Grand Historian was not convinced that the fourth-century historian was the author of the Taoteching — certainly he had more documents at his disposal than we now possess — I see no reason to decide in favor of a man whose only claim to fame was to prophesy the ascendancy of the state of Ch’in, which was to bring the Chou dynasty to an end in 221 B.C.

Meanwhile, back at the archives, I think I hear Lao-tzu laughing. The archives were kept at the Chou dynasty capital of Loyang. Loyang was a Neolithic campsite as early as 3000 B.C. and a military garrison during the first dynasties: the Hsia and the Shang. When the state of Chou overthrew the Shang in 1122 B.C., the Duke of Chou built a new, subsidiary capital around the old garrison. He dubbed it Wangcheng: City of the King. Usually, though, the Chou dynasty king lived in one of the new dynasty’s two western capitals of Feng and Hao, both of which were just west of the modern city of Sian/Xian. But when these were destroyed in 771 B.C., Wangcheng became the sole royal residence. And this was where Lao-tzu spent his time recording the events at court.

And Lao-tzu must have been busy. When King Ching died in 520 B.C., two of his sons, Prince Chao and Prince Ching, declared themselves his successor. At first Prince Chao gained the upper hand, and Prince Ching was forced to leave the capital. But with the help of other nobles, Prince Ching soon returned and established another capital fifteen kilometers to the east of Wangcheng, which he dubbed Chengchou: Glory of Chou. And in 516 B.C., Prince Ching finally succeeded in driving his brother from the old capital.

In the same year, the keeper of the Royal Archives, which were still in Wangcheng, received a visitor from the state of Lu. The visitor was a young man named K’ung Fu-tzu, or Confucius. Confucius was interested in ritual and asked Lao-tzu about the ceremonies of the ancient kings.

According to Ssu-ma Ch’ien, Lao-tzu responded with this advice: “The ancients you admire have been in the ground a long time. Their bones have turned to dust. Only their words remain. Those among them who were wise rode in carriages when times were good and slipped quietly away when times were bad. I have heard that the clever merchant hides his wealth so his store looks empty and that the superior person acts dumb so he can avoid calling attention to himself. I advise you to get rid of your excessive pride and ambition. They won’t do you any good. This is all I have to say to you.” Afterward, Confucius told his disciples, “Today when I met Lao-tzu, it was like meeting a dragon.”

The story of this meeting appears in a sufficient number of ancient texts to make it unlikely that it was invented by Taoists. Confucian records also report it taking place. According to the traditional account, Lao-tzu was eighty-eight years old when he met Confucius. If so, and if he was born in 604 B.C., the two sages would have met in 516 B.C., when Confucius would have been thirty-five. So it is possible.

Following his meeting with Confucius, Lao-tzu decided to take his own advice, and he left the capital by oxcart. And he had good reason to leave. For when Prince Chao was driven out of Wangcheng by his brother, he took with him the royal archives, the same archives of which Lao-tzu was in charge. If Lao-tzu needed a reason to leave, he certainly had one in 516 B.C.

HANKU PASS. Midway between the Chou dynasty’s eastern and western capitals and situated between the Yellow River and the Chungnan Mountains. This is where Lao-tzu met Yin Hsi, Warden of the Pass. Photo by Bill Porter.

With the loss of the archives, Lao-tzu was out of a job. He was also, no doubt, fed up with the prospects for enlightened rule in the Middle Kingdom. Hence, he headed not for his hometown of Huhsien, 300 kilometers to the east, but for the Hanku Pass, which was 150 kilometers west of Loyang, and which served as the border between the Chou dynasty’s central states and the semibarbarian state of Ch’in, which controlled the area surrounding the dynasty’s former western capitals.

As keeper of the Royal Archives, Lao-tzu no doubt supplied himself with the necessary documents to get through what was the most strategic pass in all of China. Hardly wide enough for two carts, it forms a seventeen-kilometer-long defile through a plateau of loess that has blown down from North China and accumulated between the Chungnan Mountains and the Yellow River over the past million years. In ancient times, the Chinese said that whoever controlled Hanku Pass controlled China. It was so easy to defend that during the Second World War the Japanese army failed to break through it, despite finding no difficulty in sweeping Chinese forces from the plains to the east.

Artist’s depiction of Loukuantai on tiles. Photo by Bill Porter.

Lao-tzu was expected. According to Taoist records, Master Yin Hsi was studying the heavens far to the west at the royal observatory of the state of Ch’in at a place called Loukuantai. One evening he noticed a purple vapor drifting from the east and deduced that a sage would soon be passing through the area. Since he knew that anyone traveling west would have to come through Hanku Pass, he proceeded to the pass.

Ssu-ma Ch’ien, however, says Yin Hsi was the Warden of the Pass and makes no mention of his association with Loukuantai. The connection with Loukuantai is based on later, Taoist records. In any case, when Lao-tzu appeared, Yin Hsi recognized the sage and asked for instruction. According to Ssu-ma Ch’ien, Lao-tzu then gave Yin Hsi the Taoteching and continued on to other, unknown realms.

Taoists, on the other hand, agree that Lao-tzu continued on from Hanku Pass, but in the company of Yin Hsi, who invited the sage to his observatory 250 kilometers to the west. Taoists also say Lao-tzu stopped long enough at Loukuantai to convey the teachings that make up his Taoteching and then traveled on through the Sankuan Pass, another 150 kilometers to the west, and into the state of Shu. Shu was founded by a branch of the same lineage that founded the state of Ch’u, although its rulers revered the cuckoo rather than the bear. And in the land of the cuckoo, Lao-tzu finally achieved anonymity as well as immortality.

Curiously, about six kilometers west of Loukuantai, there’s a tombstone with Lao-tzu’s name on it. The Red Guards knocked it down in the 1960s, and when I first visited Loukuantai, in 1989, it was still down. It has since been propped back up, and a small shrine built to protect it. On that first visit, I asked Loukuantai’s abbot, Jen Fa-jung, what happened to Lao-tzu. Did he continue on through Sankuan Pass, or was he buried at Loukuantai? Master Jen suggested both stories were true. As Confucius noted, Lao-tzu was a dragon among men. And being a member of the serpent family, why should we wonder at his ability to leave his skin behind and continue on through cloud-barred passes?

And so Lao-tzu, whoever he was and whenever he lived, disappeared and left behind his small book. The book at first didn’t have a title. When writers like Mo-tzu and Wen-tzu quoted from it in the fifth century B.C., or Chuang-tzu and Lieh-tzu in the fourth century B.C., or when Han Fei explained passages in the third century B.C. and Huai-nan-tzu in the second century B.C., they simply said, “Lao-tzu says this” or “Lao Tan says that.” And so people started calling the source of all these quotes Laotzu.

Ssu-ma Ch’ien also mentioned no title. He said only that Lao-tzu wrote a book, and it was divided into two parts. About that same time, people started calling these two parts The Way and Virtue, after the first lines of verses 1 and 38. And to these were added the honorific ching, meaning “ancient text.” And so Lao-tzu’s book was called the Tao-te-ching, the Book of Tao and Te.

In addition to its two parts, it was also divided into separate verses. But, as with other ancient texts, the punctuation and enumeration of passages were left up to the reader. About the same time that Ssu-ma Ch’ien wrote his biography of Lao-tzu and people started calling the book the Taoteching, Yen Tsun produced a commentary in the first century B.C. that divided the text into seventy-two verses. A century earlier, or a couple of centuries later, no one knows which, Ho-shang Kung divided the same basic text into eighty-one verses. And a thousand years later, Wu Ch’eng tried a sixty-eight-verse division. But the system that has persisted through the centuries has been that of Ho-shang Kung.

The text itself has seen dozens of editions containing anywhere from five to six thousand characters. The numerical discrepancy is not as significant as it might seem, as it is largely the result of adding certain grammatical particles for clarity or omitting them for brevity. The greatest difference among editions centers not on the number of characters but on the rendering of certain phrases and the presence or absence of certain lines.

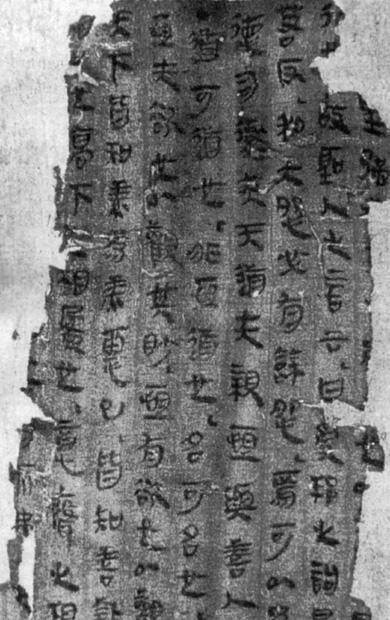

MAWANGTUI TEXT A. Written on silk shortly before 206 B.C., the text here shows verse 1 following verse 79, an arrangement unique to the Mawangtui texts. Photo by Steven R. Johnson.

Over the centuries, several emperors have even taken it upon themselves to resolve disputes concerning the choice among these variants. And the creation of standard editions resulted from their efforts. However, the standard editions were still open to revision, and every student seeking to understand the Taoteching repeats the process of choosing among variants.

In this regard, Taoteching studies were blessed in late 1973 with the discovery of two copies of the text in an ancient tomb. The tomb was located in the village of Mawangtui, a suburb of Changsha, the provincial capital of Hunan, and was sealed in 168 B.C. Despite the lapse of over 2,100 years, the copies, both written on silk, were in remarkably good condition.

Kao Chih-hsi, who supervised their removal and who directed the Mawangtui Museum for many years, attributes their preservation to layers of clay and charcoal that covered the tomb. At least this is his official explanation. In private, he says their preservation might have also been due to the presence of an unknown gas created by the decomposition of certain substances inside the tomb. He tried to take a sample of the gas, but the discovery was made in the middle of the Cultural Revolution, and he spent two days peddling his bicycle around Changsha before he found anyone who would loan him the necessary equipment. By then the gas was gone.

The books, though, made up for his disappointment. Along with the Taoteching, there were several hitherto unknown commentaries on the Yiching as well as a number of lost texts attributed to the Yellow Emperor. The Chinese Academy of Sciences immediately convened a committee of scholars to examine these texts and decipher illegible sections.

In the years since their discovery, the two Mawangtui copies of the Taoteching have contributed greatly to the elucidation of a number of difficult and previously misunderstood passages. Without them, I would have been forced to choose among unsatisfactory variants on too many occasions. Still, the Mawangtui texts contain numerous omissions and errors and need to be used with great care.

Fortunately, we have another text that dates from the same period. Like the Mawangtui texts, it was discovered in a tomb that was sealed shortly after 200 B.C. This tomb was located near the Grand Canal town of Hsuchou and was opened in A.D. 574. Not long afterward, the court astrologer, Fu Yi, published an edition of the copy of the Taoteching found inside.

In addition to the Mawangtui and Fuyi texts, we also have more than sixty copies that were found shortly after 1900 in the Silk Road oasis of Tunhuang. Most of these date from the eighth and ninth centuries. However, one of them was written by a man named Suo Tan in A.D. 270, giving us yet another early handwritten edition to consider.

We also have a copy of the Taoteching written by the great fourth-century calligrapher Wang Hsi-chih, as well as a dozen or so steles on which various emperors had the text carved. Finally, we have the text as it appears in such early commentaries as those of Yen Tsun, Ho-shang Kung, and Wang Pi, not to mention numerous passages quoted in the ancient works of Mo-tzu, Wen-tzu, Chuang-tzu, Lieh-tzu, Han Fei, Huai-nan-tzu, and others.

In undertaking this translation, I have consulted nearly all of these editions and have produced a new recension incorporating my choices among the different readings. For the benefit of those able to read Chinese, I have included the resulting text with my translation. I have also added a number of commentaries.

Over the centuries, some of China’s greatest thinkers have devoted themselves to explaining the Taoteching, and no Chinese would consider reading the text without the help of at least one of these line-by-line or verse-by-verse explanations. When I first decided to translate the Taoteching, it occurred to me that Western readers are at a great disadvantage without the help of such materials. To remedy this, I have collected several dozen of the better-known commentaries, along with a few that are more obscure. And from these I have selected passages that provide important background information or insights.

Among the commentaries consulted, the majority of my selections come from a group of eleven men and one woman. In order of frequency of appearance, they include Su Ch’e, Ho-shang Kung, Wu Ch’eng, Wang Pi, Te-ch’ing, Sung Ch’ang-hsing, Li Hsi-chai, Lu Hui-ch’ing, Wang P’ang, Ch’eng Hsuan-ying, the Taoist nun Ts’ao Tao-ch’ung, and Wang An-shih. For the dates and a minimal amount of biographical information on these and other commentators, readers are directed to the glossary at the back of the book.

Readers will notice that I have restricted the comments to what could fit on facing pages. The reason for this is that I envisioned this book as a conversation between Lao-tzu and a group of people who have thought deeply about his text. And I wanted to have everyone, including the reader, in the same room, rather than in adjoining suites.

I have also added a few remarks of my own, though I have usually limited these to textual issues. In this regard, I have tried to restrict myself to those lines where my choice among variants may have resulted in a departure from other translations that readers might have in their possession. The Taoteching is, after all, one of the most translated books in the world, exceeded in this regard only by the Bible and the Bhagavad Gita.

The text was first translated into a Western language by the Jesuit missionary Joseph de Grammont, who rendered it into Latin shortly before 1788. Since then, more than a hundred translations have been published in Western languages alone (and no doubt hundreds more distributed privately among friends). Thus, readers could not be blamed for wondering if there isn’t something inherent in the text that infects Westerners who know Chinese, and even those who don’t, with the thought that the world needs yet another translation, especially one that gets it right.

My own attempt to add to this ever-growing number dates back nearly twenty-five years to when I attended a course in Taiwan given by John C.H. Wu. Professor Wu had himself produced an excellent English translation of the Taoteching, and he offered a course on the subject to graduate students in the philosophy department of the College of Chinese Culture, which I was attending between stays at Buddhist monasteries.

Once a week, six of us filed past the guards at the stately Chungshanlou on Yangmingshan, where the government held its most important meetings and where Professor Wu lived in a bungalow provided to him in recognition of his long and distinguished service to the country. In addition to translating the Taoteching, Professor Wu also translated the New Testament, drafted his country’s constitution, and served as China’s ambassador to the Vatican and its chief representative to the Hague.

One afternoon every week, we sipped tea, ate his wife’s cookies, and discussed a verse or two of Lao-tzu’s text. Between classes, I tried translating the odd line in the margins of Professor Wu’s bilingual edition, but I did not get far. The course lasted only one semester, after which I moved to a Buddhist monastery in the hills south of Taipei and put aside Lao-tzu’s text in favor of Buddhist sutras and poetry. But ever since then, I have been waiting for an opportunity to dust off this thinnest of ancient texts and resume my earlier attempt at translation.

The opportunity finally presented itself in 1993, when I returned to America after more than twenty years in Taiwan and Hong Kong. One day in the early seventies, when I was attending graduate school at Columbia University, Professor Bielenstein quoted W.A.C.H. Dobson, who said it was time for a Sinologist to retire when he announced he was working on a new translation of the Taoteching. Having joined the ranks of those who spend their days at home, I figured I now qualified. Dobson’s remarks, I suspect, were intended more as friendly criticism of the presumption that translating the Taoteching entails. Though relatively brief, it’s a difficult text. But it’s also a transparent one.

For the past two years, ever since I began working on my own presumptive addition to the world’s Taoteching supply, one image that has repeatedly come to mind is skating on a newly frozen lake near my home in Idaho when I was a boy. Sometimes the ice was so clear, I felt like I was skating across the night sky. And the only sounds I could hear were the cracks that echoed through the dark, transparent depths. I thought if the ice ever gave way I would find myself on the other side of the universe. And I carried ice picks just in case I had to pull myself out. The ice never broke. But I’ve been hearing those cracks again.

Red Pine

First Quarter, Last Moon, Year of the Pig

Port Townsend, Washington