13

|

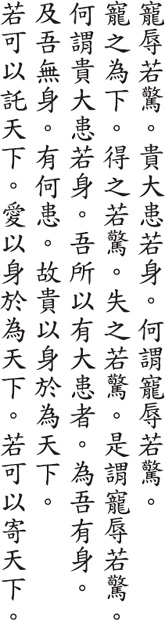

Favor and disgrace come with a warning honor and disaster come with a body why do favor and disgrace come with a warning favor turns into disfavor gaining it comes with a warning losing it comes with a warning thus do favor and disgrace come with a warning and why do honor and disaster come with a body the reason we have disaster is because we have a body if we didn’t have a body we wouldn’t have disaster thus those who honor their body more than the world can be entrusted with the world those who cherish their body more than the world can be encharged with the world |

WANG CHEN says, “People who are favored are honored. And because they are honored, they act proud. And because they act proud, they are hated. And because they are hated, they are disgraced. Hence, sages consider success as well as failure to be a warning.”

SU CH’E says, “The ancient sages worried about favor as much as disgrace, because they knew that favor is followed by disgrace. Other people think favor means to ascend and disgrace means to descend. But favor cannot be separated from disgrace. Disgrace results from favor.”

HO-SHANG KUNG says, “Those who gain favor or honor should worry about being too high, as if they were at the edge of a precipice. They should not flaunt their status or wealth. And those who lose favor and live in disgrace should worry more about disaster.”

LU NUNG-SHIH says, “Why does favor become disgrace and honor become disaster? Favor and honor are external things. They don’t belong to us. When we try to possess them, they turn into disgrace and disaster.”

SSU-MA KUANG says, “Normally a body means disaster. But if we honor and cherish it and follow the natural order in our dealings with others, and we don’t indulge our desires, we can avoid disaster.”

HUANG YUAN-CHI says, “We all possess something good and noble that we don’t have to seek outside ourselves, something that the glory of power or position cannot compare with. People need only start with this and cultivate this without letting up. The ancients said, ‘Two or three years of hardship, ten thousand years of bliss.’”

WANG P’ANG says, “It isn’t a matter of having no body but of guarding the source of life. Only those who refuse to trade themselves for something external are fit to receive the kingdom.”

WANG PI says, “Those who are affected by favor and disgrace or honor and disaster are not fit to receive the kingdom.”

TSENG-TZU says, “The superior person can be entrusted with an orphan or encharged with a state and be unmoved by a crisis” (Lunyu: 8.6).

The first two lines are clearly a quote, but commentators disagree about how to read them: are “favor” and “honor” verbs and “disgrace” and “disaster” their noun objects (“favor disgrace as a warning / honor disaster as your body”)? Or are they both nouns, as I have read them? There is also the issue of how to read juo. Normally, it means “like” or “as.” But it can also mean “to lead to,” which is how Ho-shang Kung reads it, or “to entail” or “to come with,” which is how I read it. An unusual usage, but it is after all a quote. Note, too, that in lines fourteen and sixteen, juo means “then,” which I have left implied. In line three, the Kuotien texts, as well as some other editions (but not the Fuyi, Wangpi, or Mawangtui texts), omit juo-ching, “come with a warning.” The last four lines are also found in Chuangtzu: 11.2, where they are used to praise the ruler whose self-cultivation doesn’t leave him time to meddle in the lives of his subjects. They also appear in Huainantzu: 12, where they are used to praise the ruler who values the lives of his people more than the territory in which they live. In both cases, they agree with the Mawangtui version of lines thirteen and fifteen in reading yu-wei-t’ien-hsia, “more than the world,” instead of the standard wei-t’ien-hsia, “as the world.”