15

|

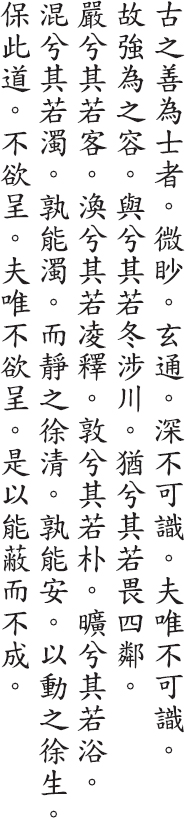

The great masters of ancient times focused on the indiscernible and penetrated the dark you would never know them and because you wouldn’t know them I describe them with reluctance they were careful as if crossing a river in winter cautious as if worried about neighbors reserved like a guest ephemeral like melting ice simple like uncarved wood open like a valley and murky like a puddle but those who can be like a puddle become clear when they’re still and those who can be at rest become alive when they’re roused those who treasure this Way don’t try to be seen not trying to be seen they can hide and stay hidden |

TS’AO TAO-CH’UNG says, “Although the ancient masters lived in the world, no one thought they were special.”

SU CH’E says, “Darkness is what penetrates everything but what cannot itself be perceived. To be careful means to act only after taking precautions. To be cautious means to refrain from acting because of doubt or suspicion. Melting ice reminds us how the myriad things arise from delusion and never stay still. Uncarved wood reminds us to put an end to human fabrication and return to our original nature. A valley reminds us how encompassing emptiness is. And a puddle reminds us that we are no different from anything else.”

HUANG YUAN-CHI says, “Lao-tzu expresses reluctance at describing those who succeed in cultivating the Tao because he knows the inner truth cannot be perceived, only the outward form. The essence of the Tao consists in nothing other than taking care. If people took care to let each thought be detached and each action well considered, where else would they find the Tao? Hence, those who mastered the Tao in the past were so careful they waited until a river froze before crossing. They were so cautious, they waited until the wind died down before venturing forth at night. They were orderly and respectful, as if they were guests arriving from a distant land. They were relaxed and detached, as if material forms didn’t matter. They were as uncomplicated as uncarved wood and as hard to fathom as murky water. They stilled themselves to concentrate their spirit, and they roused themselves to strengthen their breath. In short, they guarded the center.”

WANG PI says, “All of these similes are meant to describe without actually denoting. By means of intuitive understanding the dark becomes bright. By means of tranquillity, the murky becomes clear. By means of movement, the still becomes alive. This is the natural Way.”

WANG CHEN says, “Those who treasure the Way fit in without making a show and stay forever hidden. Hence, they don’t leave any tracks.”

It would seem that Lao-tzu is also describing himself here. In line two, I have followed Mawangtui B in reading miao (aim/focus) for miao (mysterious). In lines fourteen and sixteen, I have followed the Kuotien, Wangpi, and Fuyi texts in adding shu-neng (who can) to the beginning of both lines. In line nineteen, I have followed the Kuotien texts, which have ch’eng (reveal) in place of the usual ying (full), and I have amended line twenty (again replacing ying with ch’eng) to fit this reading. Other variants of the last line include: “they can be old but not new” and “they can be old and again new.” My reading is based on the Fuyi edition and Mawangtui B, as well as on the interpretations of Wang Pi and Ho-shang Kung, who also read pi (hide) instead of pi (old), thus recapitulating the opening lines as well as the two lines before it. The Kuotien texts omit lines five, twelve, and the last two lines.