28

|

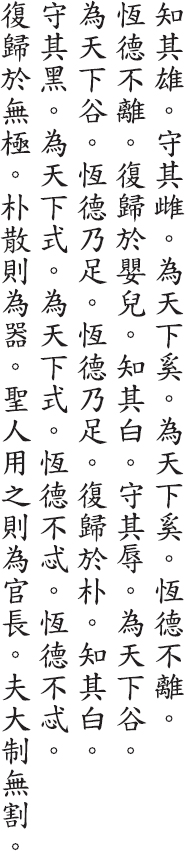

Recognize the male but hold on to the female and be the world’s maid being the world’s maid don’t lose your Immortal Virtue not losing your Immortal Virtue be a newborn child again recognize the pure but hold on to the base and be the world’s valley being the world’s valley be filled with Immortal Virtue being filled with Immortal Virtue be a block of wood again recognize the white but hold on to the black and be the world’s guide being the world’s guide don’t stray from your Immortal Virtue not straying from your Immortal Virtue be without limits again a block of wood can be split to make tools sages make it their chief official a master tailor doesn’t cut |

TE-CH’ING says, “To recognize the Way is hard. Once you recognize it, holding on to it is even harder. But only by holding on to it can you advance on the Way.”

MENCIUS says, “The great person does not lose their child heart” (Mencius: 4B.12).

WANG TAO says, “Sages recognize ‘that’ but hold on to ‘this.’ ‘Male’ and ‘female’ mean hard and soft. ‘Pure’ and ‘base’ mean noble and humble. ‘White’ and ‘black’ mean light and dark. Although hard, noble, and light certainly have their uses, hard does not come from hard but from soft, noble does not come from noble but from humble, and light does not come from light but from dark. Hard, noble, and light are the secondary forms and farther from the Way. Soft, humble, and dark are the primary forms and closer to the Way. Hence, sages return to the original: a block of wood. A block of wood can be made into tools, but tools cannot be made into a block of wood. Sages are like blocks of wood, not tools. They are the chief officials and not functionaries.”

CH’ENG HSUAN-YING says, “What has no limits is the Tao.”

CONFUCIUS says, “A great person is not a tool” (Lunyu: 2.12).

CHANG TAO-LING says, “To make tools is to lose sight of the Way.”

SUNG CH’ANG-HSING says, “Before a block of wood is split, it can take any shape. But once split, it cannot be round if it is square or straight if it is curved. Lao-tzu tells us to avoid being split. Once we are split, we can never return to our original state.”

PAO-TING says, “When I began butchering, I used my eyes. Now I use my spirit instead and follow the natural lines” (Chuangtzu: 3.2).

WANG P’ANG says, “Those who use the Tao to tailor leave no seams.”

In lines three and four, I have followed Tunhuang copies p.2584 and s.6453 in reading hsi (maid/female servant) for the standard hsi (stream) as more in keeping with the images of the preceding lines. In lines eight through twenty-one, I have followed the Mawangtui texts, which fail to support the suspicions of some commentators that these lines were interpolated. Reverence for the spirit of wood is still shared by many of the ethnic groups along China’s borders. During Lao-tzu’s day, the southern part of his own state of Ch’u was populated by the Miao, who trace their ancestry to a butterfly and the butterfly to the heart of a maple tree. It has been suggested that Lao-tzu was somehow affiliated with the Miao, if not through blood or family ancestry then marriage. This verse is not present in the Kuotien texts. Instead of the usual ch’ang (immortal/ constant), I have preferred the character heng (immortal/constant), present in both Mawangtui texts, as it also means “crescent moon” and is used by Lao-tzu elsewhere in the Taoteching with both the lunar image and immortality in mind, as in verse 1. The last four lines recall the images and wording of the first two lines in verse 16.