54

|

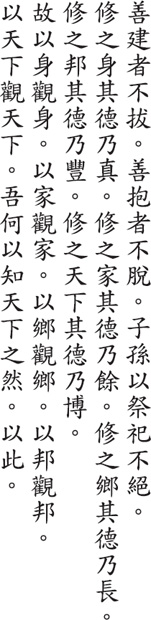

What you plant well can’t be uprooted what you hold well can’t be taken away your descendents will worship this forever cultivated in yourself virtue becomes real cultivated in your family virtue grows cultivated in your village virtue multiplies cultivated in your state virtue abounds cultivated in your world virtue is everywhere thus view others through yourself view families through your family view villages through your village view states through your state view other worlds through your world how do you know what other worlds are like through this one |

WU CH’ENG says, “Those who plant something well, plant it without planting. Thus, it is never uprooted. Those who hold something well, hold it without holding. Thus, it is never taken away.”

WANG AN-SHIH says, “What we plant well is virtue. What we hold well is oneness. When virtue flourishes, distant generations give praise.”

TS’AO TAO-CH’UNG says, “First improve yourself, then reach out to others and to later generations bequeath the noble, pure, and kindly Tao. Thus, blessings reach your descendants, virtue grows, beauty lasts, and worship never ends.”

SUNG CH’ANG-HSING says, “In ancient times, ancestral worship consisted in choosing an auspicious day before the full moon, in fasting, in selecting sacrificial animals, in purifying the ritual vessels, in preparing a feast on the appointed day, in venerating ancestors as if they were present, and in thanking them for their virtuous example. Those who cultivate the Way likewise enable later generations to enjoy the fruits of their cultivation.”

HO-SHANG KUNG says, “We cultivate the Tao in ourselves by cherishing our breath and by nourishing our spirit and thus by prolonging our life. We cultivate the Tao in our family by being loving as a parent, filial as a child, kind as an elder, obedient as the younger, dependable as a husband, and chaste as a wife. We cultivate the Tao in our village by honoring the aged and caring for the young, by teaching the benighted and instructing the perverse. We cultivate the Tao in our state by being honest as an official and loyal as an aide. We cultivate the Tao in the world by letting things change without giving orders. Lao-tzu asks how we know that those who cultivate the Tao prosper and those who ignore the Tao perish. We know by comparing those who don’t cultivate the Tao with those who do.”

YEN TSUN says, “Let your person be the yardstick of other persons. Let your family be the level of other families. Let your village be the square of other villages. Let your state be the plumb line of other states. As for the world, the ruler is its heart, and the world is his body.”

CHUANG-TZU says, “The reality of the Tao lies in concern for the self. Concern for the state is irrelevant, and concern for the world is cowshit. From this standpoint, the emperor’s work is the sage’s hobby and is not what develops the self or nourishes life” (Chuangtzu: 28.3).

The same sentiments were echoed by Confucius in the Tahsueh (Great Learning): “The ancients who wished to manifest Virtue in the world first ordered their states. Wishing to order their states, they first harmonized their families. Wishing to harmonize their families, they first cultivated themselves. Wishing to cultivate themselves, they first perfected their minds. Wishing to perfect their minds, they first rectified their thoughts. Wishing to rectify their thoughts, they first deepened their knowledge” (4). As in verse 36, Mawangtui A has pang (state), while Mawangtui B has the synonym kuo (country), suggesting A was copied before 206 B.C., when the use of pang was forbidden, as it was part of the emperor’s name. In line nine, both Mawangtui texts omit ku (thus), while the Fuyi and Wangpi editions include it. The Kuotien texts omit line nine. The meaning of the last seven lines is similar to that of the line in the poem “Carving an Ax Handle” in the Book of Songs: “In carving an ax handle, the pattern is not far off.”