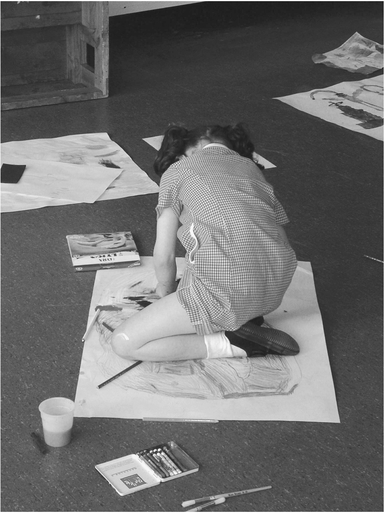

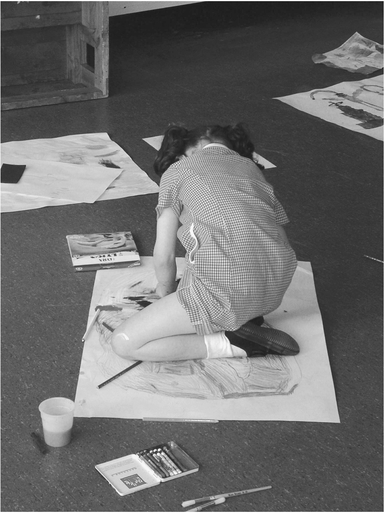

Figure 1.3.1 Lost in drawing. A research workshop in progress. Photograph Brian Hartley Copyright Matthew Reason

Matthew Reason

What am I asking, if I ask a research participant to draw me a picture?

In different guises this request has been asked of participants across psychology, health, education, marketing and my own context of arts audience research. In all these areas, and others, the invitation to draw has become one of a range of visual methodologies recognized as having great potential when conducting research with people.

The use of drawing is often described as a ‘projective technique’, motivated by the perception that when responding to direct questioning research participants may either be reluctant or not consciously able to reveal their true attitudes or deepest feelings. To address this difficulty, researchers use methods designed to enable participants to ‘project’ their feelings through mediating activities. Examples include the use of word association tests, sentence and story completion, photo sorts and indeed drawing. Drawing is utilized in this manner in contexts as diverse as market research – to circumvent participants’ self-consciousness and ‘delve below surface responses to obtain true feelings, meanings or motivations’ (McDaniel and Gates 1999: 152) – and art therapy – where its use is ‘based on the accepted belief that drawings represent the inner psychological realities and the subjective experiences of the person who creates the images’ (Malchiodi 1998: 5).

There are, however, a variety of contentious propositions here, both ethical and methodological, particularly in the assertion that a drawing methodology reveals truths below the surface of the participant’s consciousness. Art therapy, in particular, has moved away from an overly ‘diagnostic’ use of drawing, where the expert therapist asserts their ability to know the experience and feeling of the participant through the content of the drawing alone. Instead, drawing as a research methodology has become fundamentally connected to participants’ talk about drawing. That is, participants are perceived as ‘expert’ in their own experiences and positioned as the first and most important interpretation of their own drawings. This is the case both in therapeutic (Malchiodi 1998) and research (Gauntlett 2007) contexts.

As a ‘draw and talk’ methodology, drawing is no longer an almost magical process that is revelatory of inner or authentic truths. If we ask a research participant to draw we cannot presume that this necessarily makes the responses more insightful, or more complete, or more anything else than those communicated by talk alone. It is, however, a request that constructs a specific dynamic between researcher, participant and the subject/object of enquiry that has the potential to produce different kinds of insights and understandings (see for example Elliot Eisner (2008) on visual knowledge).

When I ask a participant to draw me a picture I am inviting a different dynamic than if I had simply asked them to talk. I do not expect them to respond instantly. Instead drawing imposes a slowing down, a pause for reflection in the returning to memories. Yet, and this is vital, it is not simply a pause for thought (and I might very well ask a participant to have a think about something for a few minutes before answering). More specifically, it is a pause to draw.

Figure 1.3.1 Lost in drawing. A research workshop in progress. Photograph Brian Hartley Copyright Matthew Reason

Drawing is an activity in which the marks made on paper – with pencil, crayon, ink, pen – appear instantly, they are real and absolute, but which also requires us to spend time with our thoughts, memories or experiences as we begin, develop and complete a drawing. This combination of duration and immediacy is the unique quality of drawing as a research methodology. It is at once an active doing and also a quieter, reflective thinking. Through this duration it is possible for thoughts, realizations or insights to come into knowing in a manner that is less about discovering something pre-existing and more about constructing knowledge through the process itself.

While the nature of drawing is much debated within art theory, ‘drawing’ as an arts-based or creative research methodology is typically framed fairly broadly and rarely narrowly conceived in terms of media or materials. In my own practice, I have tended to provide participants with a diverse range of arts materials and allowed them to select those that most suit their temperament or the nature of what they want to communicate. The results often go beyond the qualities of line to include elements such as colour and texture, producing artefacts that might at times be closer to painting or even collage (when participants elect not to draw on paper but rather rip it up and ‘draw’ with paper). Visual or expressive ‘mark making’ might, therefore, be a more accurate if less evocative description for the diversity of creative processes that participants employ. Considered either as drawing or mark making, participants are required not only to spend time with memories, thoughts and feeling but also to start to externalize these visually. The mark is both of the participant, and yet also separate from them; it is, as Joseph Beuys puts it, the changing point at which ideas become ‘the visible thing’ (Rose 1993). Mark making therefore operates for participants as both a form of research (what is it I know about this memory? What did I see? What do I remember?) and of expression (how did it make me feel? What did I think about it?). The result is a process of reflective contemplation, as participants’ responses are mediated through the act of making a mark – a line, a shape, a trace, a shade – with this active doing enabling a dialogic process between participant and an art work that is exterior to them.

My own research focuses on audiences’ memories, experiences and perceptions of theatre and dance performances. A typical scenario might involve accompanying a group of child or adult audience members to a performance and then facilitating an arts workshop with them. Audiences often like to talk about the performance they have seen, and implicit within the drawing workshops is the desire to slow down and extend this desire to share and externalize the experience. In this context, the particular request is for the participants to ‘draw something you remember from the performance’.

In my own practice this request is framed and structured with care. The workshops begin with warm-up drawing games – getting the participants to ‘take a line for a walk’ or draw portraits of themselves with their ‘wrong’ hand. As researcher, I join in these exercises, using all of our drawings as an opportunity to explain that I am not concerned with the relative quality of the pictures. Here it is worth noting that drawing as an activity is experienced very differently by adult and child participants. As Pia Christiansen writes, children themselves consider ‘all’ children to be competent at drawing, which to them is an ordinary rather than specialized activity (Christensen and James 2000: 167). When working with children, therefore, drawing feels a natural activity and following the introductory exercises the workshops consist of an extended period of largely free drawing. As the children draw I will talk to them, individually or in pairs, asking them to tell me about their drawing and through that about the performance they witnessed.

For most adults, in contrast, drawing is not an everyday activity and many grown-ups will automatically assert that they ‘can’t draw’. For this reason, running art workshops with adults requires additional structured elements, continuing the drawing exercises through the whole process with further suggestions designed to distance participants from their self-consciousness about drawing. So, for example, participants might be invited to draw with their eyes closed, without taking their pencil off the paper, or on a large sheet of paper while using a pen taped to the end of a two-metre-long bamboo cane.

Whether with children or adults, the process of drawing invites participants to spend time with their memories and experiences. In making the decision of what to draw and how to draw it, participants are required to invest effort and project themselves into their art work and into their memories. Drawing represents a prompt to consider what things looked like, what things meant and how things felt. Or, more accurately, to discover this knowledge through the process of drawing. Here a couple of examples are useful.

A seven-year-old girl draws a puppet goose from the theatre performance she saw in her school hall. But she does so not as a puppet and not from the perspective given to her in the performance. Instead this goose is a fully fledged bird, depicted flying high above the stage, which is shown as small and far below. In the picture the goose is crying. The drawing depicts something not literally seen in the performance and from a perspective different from that of the audience. While prompted by the performance, the detail and specificity of these acts of imagination and empathy are only fully realized through the requirement to draw.

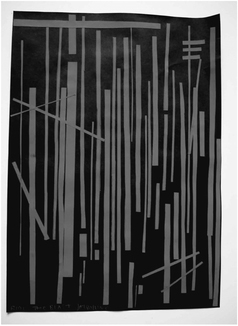

In another example, a woman in her 40s constructs a collage by slowly and laboriously cutting and sticking long red strips of card to a black sheet of paper. As she works she comments of the dance performance she had seen: ‘I mostly got a feeling from it, I got a kind of sense of it being very, very angular and full of energy. But with a real kind of tension there.’ Here the content and materiality of the picture echoes the memory, constructing a visceral, sensory response to the performance. Both the picture and the performance are an expression of angles and staccato tension.

Figure 1.3.2 Crying goose. Child’s drawing of Martha by Catherine Wheels Theatre Company. Copyright Matthew Reason

In very different ways – one abstract and the other figurative – these examples display a sympathy between the visual depiction and the emotional meaning invested into the memory. In other words, the process of responding visually requires the participants to look again, look closer and through investing themselves into the memory depict more than they had seen – adding, interpreting, imagining, playing. The verbal responses, therefore, are the product not just of the original experience but also of the artistic intervention into that experience.

Figure 1.3.3 Angular and full of energy. Adult’s collage of Ride the Beast by Scottish Ballet/ Stephen Petronio. Copyright Matthew Reason

It is important to note that the transformative impact of the creative process is not generic but specific to the particularities of the methodology of visual expression, as manifested, for example, in the challenge of representing a theatre or dance performance on paper and the manner by which the participants engaged with the materiality of art making. The making of a picture takes time: thoughts and intentions at the beginning change and evolve as the image develops. Participants did not simply decide what to depict, but rather discovered both the what and how of the (re)presentation in the act of doing. As one of the adult participants in a research workshop commented:

I thought the interesting thing for me when doing the art work was that I started with something but I started a dialogue with my image. So I started to put in other things that weren’t there. But they were thoughts and feelings, so it opened up a conversation with myself about my memory of what I’d seen.

While the possibility of invention might concern a researcher seeking some externalized truth, for me this notion of a dialogue between the research participant and their experience is both striking and useful. In my research, I am interested in exploring audiences’ aesthetic, embodied and emotional experiences of theatre and dance. These are by definition ephemeral and often seem both intangible and ineffable. Indeed, John Carey suggests that not only are the aesthetic experiences of other people impossible to access, but in truth our own aesthetic experiences are largely unapparent even to ourselves (2006: 23). Aesthetic experiences, therefore, can be considered not as something that participants know and simply have to tell, but instead as something that is brought into being by the process of reflection. Experience here is not only had, but also made.

The transformative process of drawing as a creative expression should, therefore, be considered a process through which new and different kinds of knowledge are generated and communicated. This is central to much artistic research and can be seen in terms of what Henk Borgdorff (2010: 61) describes as ‘the pre-reflective, non-conceptual content of art’ that ‘creates room for what is unthought, that which is unexpected’. It is a process that is not linear or fully planned, but equally not fully unintentional. Along with other forms of visual expression, drawing is not simply a projective technique, but a form of structured exploration and generation. It is an approach particularly suited to researching emotional or affective memories, where the interest is in the lived phenomenological experience of the participant. Drawing, potentially at least, is a process that exposes the unthought and the unexpected, often not just to the researcher, but also to the participants themselves.

Borgdorff, H. (2010). The production of knowledge in artistic research. In M. Biggs and H. Karlsson (Eds.) The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts (pp. 44–63). London: Routledge.

Carey, J. (2006). What Good Are the Arts? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Christensen, P. and James, A. (Eds.) (2000). Research with Children: Perspective and Practices. London: Falmer Press.

Eisner, E. (2008). Art and knowledge. In J. G. Knowles and A. L. Cole (Eds.) Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research (pp. 3–12). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gauntlett, D. (2007). Creative Explorations. Abingdon: Routledge.

Malchiodi, C. (1998). Understanding Children’s Drawings. London: Jessica Kingsley.

McDaniel, C. and Gates, R. (1999). Contemporary Marketing Research. Cincinnati, OH: South Western College.

Rose, B. (1993). Joseph Beuys and the language of drawing. In A. Temkin and B. Rose (Eds.) Thinking is Form: The Language of Joseph Beuys (pp. 73–118). London: Thames and Hudson.