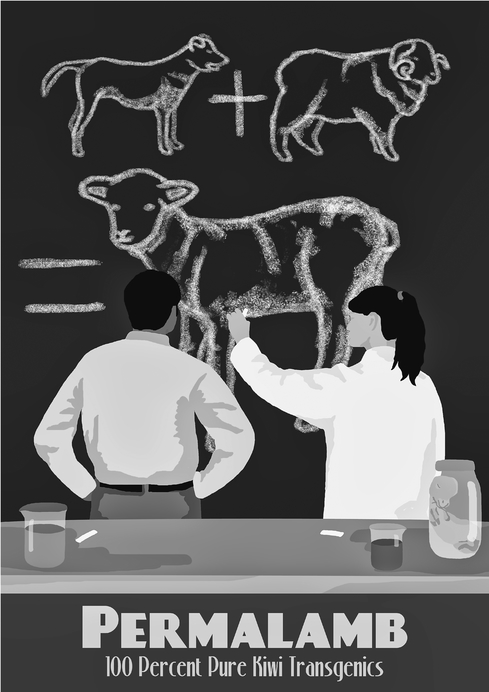

Figure 5.10.1 PermaLamb: 100 percent pure Kiwi transgenics (copyright Anne Galloway and Lauren Wickens)

Anne Galloway

The following entry can be found in the Encyclopædia of New Zealand History, published 6 March 2032, at Tāupo, New Zealand.

On 7 June 2019, in an unprecedented show of national cooperation, all of the country’s political parties unanimously voted in favour of creating the NZ Ministry of Science and Heritage. For the first time in over 150 years, there were fewer sheep than people on our islands, and the new ministry’s mandate was to ensure the protection of NZ’s past and future. Within a few weeks, a meeting was convened in Oamaru, bringing together the nation’s best scientists, historians, engineers, artists, economists and religious leaders to re-imagine our national icon – and so a new species was born.

Using well-established transgenics research and recombinant DNA techniques, select genes from prize-winning NZ huntaway dogs were introduced into the genetic sequence of the finest NZ merino sheep, and development halted at the juvenile stage. The resulting cross-bred animal embodied the behavioural traits of a dog and took on the physical appearance of a lamb for its entire life, making it the perfect companion species. Each PermaLamb would also be implanted with a full suite of networked identification, location and sensor technologies, enabling it to generate and collect petabytes of data over its lifetime.

The National PermaLamb Programme was launched on 12 August 2021 with government incubators and dispensaries set up in each region of the North and South Islands. To ensure the growth of the nation’s new flock, every citizen and permanent resident of New Zealand over the age of 18 was required to adopt a PermaLamb and, in return, offered tax credits.

Ministry agents began meeting all international visitors at our ports in order to recruit PermaLamb foster-programme participants, and offer credit toward any future immigration applications. Almost immediately, people started camping outside ministry offices so that they could be among the first PermaLamb caregivers, and animals quickly became back-ordered from our national laboratories.

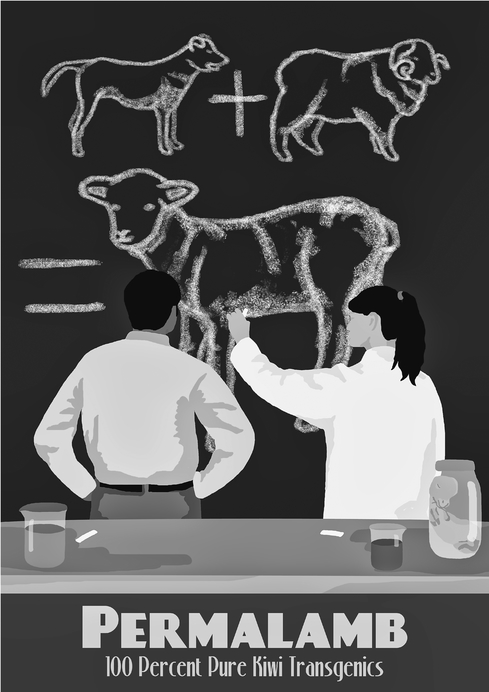

Nonetheless, within days the National PermaLamb Flock started to provide us with invaluable environmental data, and TVNZ began broadcasting each region’s average temperature, humidity,

Figure 5.10.1 PermaLamb: 100 percent pure Kiwi transgenics (copyright Anne Galloway and Lauren Wickens)

Figure 5.10.2 PermaLamb: track the National PermaLamb Flock (copyright Anne Galloway and Lauren Wickens)

wind speed, soil quality, air quality and sound quality as part of the national evening news, with real-time data tracking available via the Internet.

The PermaLamb Social Network offered caregivers the opportunity to share details of their animals’ activities with friends and family, as well as to subscribe to the feeds of other PermaLambs across the country. By the end of the first year, #PermaLamb2393 and #PermaLamb38645 each had over 10 million followers from around the world. Within three years, both networks had over 4 billion combined global subscribers.

The ministry gave special attention to what it would mean to share our everyday lives with PermaLambs and still maintain our national sense of practicality and self-sufficiency. The merino’s fine wool was re-established as a preferred textile fibre, and within two years every New Zealand home developed the capacity to clothe its members.

PermaLambs eliminated the need for shearing by naturally shedding their wool, and schoolchildren often competed to see who could collect the most. Local PermaLamb parks brought communities together to play with their pets and sustainably produce their own clothing; knitting machines were activated if lambs registered as ‘happy’.

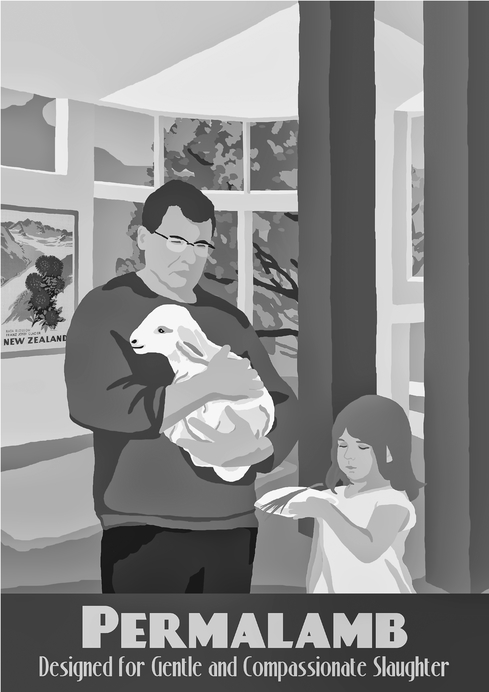

The National PermaLamb Programme’s ability to clothe the nation was accompanied by its capacity to feed us as well. Recognizing the need to identify a new source of protein for NZ’s meat-eaters, without ever sacrificing the value our country places on animal welfare, each PermaLamb came with an optional slaughter kit. Designed to be as gentle and compassionate as possible, special grasses could be fed to a PermaLamb so that it would fall asleep and never wake again.

Maintaining such a close connection to a food source was new to many of us, and previously casual barbeques and Sunday roast dinners became treasured rituals among family and friends for years to come.

*The full set of NZ’s Ministry of Science and Heritage National PermaLamb Programme posters is available from the Nation’s Archives for personal, non-commercial download and printing. Visit http://countingsheep.info/permalamb.html/ to download hi-res, A3-size images.

I make things, and make things up. Things that do not yet exist, and things that might never exist. In my research, I conjure individual relations and entire worlds. I try things on, and see how they fit. I make adjustments, and I try them on again. I show them off. I ask people if they suit, if they are beautiful or ugly. Comfortable or constricting. I ask others to try them on. And I ask what they could do in them, if they would live in them. In other words, I play dress-up and invite others to join me.

This conceit of playing dress-up is useful, I think. I first learnt to do it as a child reading fantasy books, and spending a great deal of time in fictional and other enchanted places. Putting on special clothing was an integral part of troubling my sense of self and entering these worlds, and costumes still signify a transition to new ways or states of being. As Margaret Atwood (2011: 27) notes, when considering humanity’s long history of god-kings and shamans, ‘the man or woman and the costume and regalia were almost one and the same: you were the role, and the role was the garment and its embellishments. You inhabited it rather than just wearing it’. Carnivals still bring extraordinary, if temporary, powers to ‘ordinary’ people, and fancy dress allows us to discover who we are (and are not), as well as to explore who we want (and do not want) to be.

I believe that the ability to invoke, trouble and ‘inhabit’ other worlds and worldviews is instrumental to qualitative research’s critical and creative role in knowledge-making. It is an

Figure 5.10.3 PermaLamb: designed for easy shedding and wool gathering (copyright Anne Galloway and Lauren Wickens)

Figure 5.10.4 PermaLamb: designed for gentle and compassionate slaughter (copyright Anne Galloway and Lauren Wickens)

important part of the aesthetics and ethics of what we do. Speculative design – the more intellectual, word- and image-based version of playing dress-up – can disguise or rearrange the world as we know it, and let us see it differently. It can introduce new objects and relations, and allow us to explore their implications (see, for example, Dunne and Raby 2001, 2013; DiSalvo 2012; Malpass 2017). And, at its most fantastical, it can stretch the very boundaries of social imagination and possibility. The political stakes here are not small, as Ursula K. Le Guin (2009: 40–41) so eloquently explains:

In reinventing the world of intense, unreproducible, local knowledge, seemingly by a denial or evasion of current reality, fantasists are perhaps trying to assert and explore a larger reality than we now allow ourselves. They are trying to restore the sense – to regain the knowledge – that there is somewhere else, anywhere else, where other people may live another kind of life. The literature of imagination, even when tragic, is reassuring, not necessarily in the sense of offering nostalgic comfort, but because it offers a world large enough to contain alternatives and therefore offers hope.

Speculative design ethnography is based on the promise and hope gifted by Le Guin’s fantastic. As a research method it uses actual experiences and attitudes to elicit questions rather than provide answers – although unsolicited and unexpected answers have been known to appear. It values accumulation rather than reduction. It is open, performative and generative, excessive and uncertain. It strives for resonance rather than realism, and embodies what Patti Lather (1993: 686) calls ‘voluptuous validity’, or research that:

goes too far toward disruptive excess, leaky, runaway, risky practice; embodies a situated, partial, positioned, explicit tentativeness; constructs authority via practices of engagement and self-reflexivity; creates a questioning text that is bounded and unbounded, closed and opened; brings ethics and epistemology together.

Ultimately, it is also a form of engagement that creates temporary, or mobile, publics gathered around a specific matter of concern, whose goal is to (be)come together (Galloway 2010) but not necessarily to become one. This is consistent with Dunne and Raby’s (2001) original placement of sense-making in the hands of the audience, as they expected ‘the user would become a protagonist and co-producer of narrative experience rather than a passive consumer of a product’s meaning’ (p. 46). However, this meaning may also be in partial or complete opposition to the intentions of the speculative design ethnographer.

PermaLamb – the speculative scenario that appeared at the beginning of this chapter – is part of Counting Sheep: NZ Merino Internet of Things, a three-year research project in which I conducted ethnographic research into merino wool and meat production, and how they might be affected by emerging technoscience. The second half of the project involved working with design students to ‘translate’ matters of interest and concern arising from my fieldwork into speculative design scenarios that might stimulate broader thinking around entanglements of technoscience and animals. As I was specifically interested in how speculative design ethnography might be used as a research method, matters of valuing and validating speculation were central to our work.

A total of four speculative scenarios were created and published online at http://countingsheep.info/, accompanied by a short survey. The decision to make the scenarios available online was primarily one of practicality. First, it allowed us to design objects that were not fully functional (they need only be photographed), and to focus on designing easily shared content. Second, it eliminated the need to secure physical exhibition space and manage access; however, it was also a deliberate decision to try to avoid a potentially exclusionary gallery context. The decision to work with a combination of written text and still images was also a calculated choice to experiment beyond the de facto standard of online video. Although the English-speaking Internet is neither inherently accessible nor inclusionary, the web provided stable locations for our creative content and questionnaire, and the project website continues to serve as an archive.

For potential comparison and contrast, each scenario was designed to occupy a place along a realist-fantasist spectrum: PermaLamb was the most fantastical narrative and Kotahitanga Farm (an urban exhibition farm) occupied the realist end-point. Building on a breeder’s comment that ‘Merino are a man-made animal’, and concurrent efforts by the New Zealand Merino Company to breed the ‘perfect sheep’ (http://perfectsheep.co.nz), I tried to imagine how far those ideas could be taken. Knowing that sheep and working dogs are almost always tied together on New Zealand farms offered the opportunity to combine transgenics, or cross-species breeding, with Internet of Things technologies, and PermaLamb was conceived as a means to provide a cultural context for such technoscientific developments. The overall narrative was created to be a bit tongue-in-cheek, drawing on a number of well-trodden stereotypes of New Zealand culture and familiar discourses surrounding technology and neoliberal governance. The aesthetics of our 10-poster series also directly mimicked the visual style of early to mid-century New Zealand tourism advertising (see, for example: Alsop, Stewart and Bamford 2012) and high-resolution digital copies suitable for home printing were included online.

Ultimately, our audience was global, with respondents from New Zealand, Australia, the United States, Brazil, South Africa and the UK – representing university, industry, technology, farming and government workers. But it was also quite small and notably homogeneous – we received only 54 responses to all four scenarios, and a full 40% of the respondents identified as university-affiliated, with design as the most commonly selected personal interest. These data may do little to counter concerns that speculative design speaks best, if not also predominantly, to itself – but I remain optimistic that it can. The key, I believe, will be found in process rather than product: speculative designs need to be made with others, not just shown to others. But that is a discussion for another place and time!

Although the PermaLamb scenario garnered the least attention of the four scenarios, with only six respondents (two university-affiliated, two technology-affiliated and two farm-affiliated), it was the content of these responses that led me to choose it as the case study for this chapter. Not only was the narrative considered too fantastical for some, it was also considered the most troubling in terms of both social and research ethics.

One potential ‘problem’ with fantasy is that some people will assess it in terms of its plausibility or practical realism, and find it lacking:

Of course, sheep are not indigenous to NZ . . .

I don’t know if is practical in the city [as] a lamb is not a pet, but if you have it in a special farm and you can track your lamb with a chip, could be plausible.

I’m not sure about the shedding. I think it might be better to have non-shedding animals and sheering [sic] stations (operated as lemonade stands to maintain the child engagement?). One of the complaints about dogs is shedding, so much that some of the most expensive breeds do not shed.

Using a huntaway [is a bad idea]. They are a naturally noisy breed of dog, and tend to rush things. Border collies or another suitable working breed which is easy for average people to train would make a far better end result.

Didn’t find this scenario particularly realistic. While the other two [sic] scenarios I could see working in one sense or the other, this one just didn’t sit well with me. I have never been good with, what I see as, unrealistic scenarios. My imagination doesn’t stretch quite this far, not necessarily the huntaway gene into a sheep, but more that everyone has to have one etc. Sounds like a huge disaster to me.

Nonetheless, the responses above are reasonable and demonstrate valid knowledge held by different (including ‘non-expert’) publics.

On the other hand, an ability to treat a fantasy scenario as ‘real’ allowed other respondents to raise a number of ethical concerns about human–animal relations:

The genetic modification of the PermaLamb to remain forever in ‘lamb’ state is not a good idea. The name of the scenario might hint at how central this notion is to the animal, but I think it would be terrible for pets to be ‘designed’ in this way, as I think children in particular learn about the cycle of life and death, usually, through the ageing of their pets. I think that ageing process is important in recognizing that animals also have personality. My old dog got grumpier as she aged. A permanently young animal may not encourage a whole range of empathetic insights that pets can teach kids.

It blurs the lines between product, food and pet in ways that I hadn’t thought of before. The convenience of the ‘special’ grass, the way it helps smooth over that ‘seam’ from pet to food was the most provocative. It encourages you to confront the relationship we have to animals in terms of a stark choice – is this animal cute enough to keep for a while longer? If not, no worries! Hand feed it, in a nurturing way, and then invite your friends over for the cook-up.

This scenario creates circumstances in which people can better consider the welfare of the animals that provide their clothing and food by being the relationship into the home.

Making every NZer have one [is a bad idea], not everyone is capable of taking care of animals. Creating a whole new species rather than working with, and promoting the ones that we already have [is also a bad idea].

Similarly, respondents raised ethical concerns about the roles of science and technology in society:

This scenario has linked consumerism, animal welfare and technology in new ways for me. It also highlights the moral and ethical dilemmas inherent in design, and shows how quickly the kind of utopian determinism around technology could lead to an ‘advancement’ that we, as a society, may not actually want.

I’m interested in the idea of quantifying pets and animals, and think this is the most likely to happen. ‘Augmenting’ our pets with an array of sensors and network technology is intriguing, probably from a health monitoring sense. I find this scenario most interesting when it comes to feeding data back to the animals themselves – not so much what kind of quantifiable data is possible to be captured, but whether it is possible to allow the animals themselves to act upon this data? The idea of an ad-hoc mesh network formed out of livestock or ‘companion animals’ is also really interesting, like a kind of ‘infrastructure fiction’. The data collection (IF truly private) offers an opportunity for understanding place better [but] there would need to be additional clarification about privacy protections.

Genetic engineering [is] not human’s role on the planet. Information like weather can be gathered without implanting animals with technology. Social networking is for people-to-people contact not people-to-animal. No part of this scenario illustrates people at work, the people have no life purpose. The scenario of compulsory having an ‘animal’ is in biblical terms the mark of the devil without the human having the mark.

And finally, one Australian-based university-affiliated respondent used the PermaLamb scenario to express concerns about the research project itself:

Disturbing. I think people have done enough f*cked up stuff to animals, just look at all the problems that designer dogs have with their health. I cannot believe that you got funding to come up with any of these future scenarios. It just seems that you are trying to work on behalf of the wool/sheep industry to find even more ways to exploit sheep and other animals at their expense. There are so many ethical issues that you haven’t even touched on. It is a very bad idea. This project is a classic example of the biotechnological turn in animal sciences which aims to increase the efficiency and profitability and output of animal production with little regard for ethics or animal suffering/welfare. This scenario has made me think that all New Zealand research must have to involve some sort of benefit for the sheep industry.

Created as tools for further questioning, our scenarios purposely leave open the kind of response they might inspire – and the comments immediately above suggest that research products stripped of any description of process run the risk of being interpreted (or misinterpreted) any number of ways. Speculation has long risked being conflated with prediction, and I would add it equally risks being conflated with advocacy. At no point did we identify any of the scenarios as either desirable or undesirable, but the survey asked respondents to identify elements of each. The above comment was the only one in 54 responses that seemed to assume I and/or my team wanted our scenarios to one day come true.

PermaLamb is an example of what Michael calls ‘difficult objects’ or things that:

warp the scientific and the social (as mediated by the designers) – they have implications that are good and bad, individual and collective, internal and external, biological and cultural, emancipatory and authoritarian, modest and arrogant, cruel and funny, academic and commercial, serious and playful, and of course, designerly and scientific.

Michael 2012: 542

Following Haraway (2008), our speculative design ethnography aimed ‘to build attachment sites and tie sticky knots to bind intra-acting critters, including people, together in the kinds of response and regard that change the subject – and the object’ (p. 287). But these responses and changes are not given; rather they are both more and less than what researchers may intend, expect, or hope.

Given the kind of respondents we had, we also find Michael’s (2012: 541) description of speculative design’s public to be useful:

The public seems to be composed of more or less fully rounded persons, more or less able to confront with cognitive and emotional maturity (for want of a better phrase) [the] novel . . . designerly artifacts. What is particularly interesting is that this ‘maturity’ is characterized by a capacity to entertain, deal with, and explore the confusion, ambiguity, blurriness of the issues associated with these objects. This is a tacit model of the public where its members suffer neither from intellectual deficit nor citizenly shortcomings – rather, it is a constituency whose role is not to be ‘citizenly’ (whatever form that might take) within a context of policy making, but thoughtful within a context of complexity.

And just as our speculative designs did not seek to solve problems, the kind of public engagement that arose did not provide solutions – or even agreement! Rather than seeing this as a failure of either our research or its impact, we suggest that the respondents’ thoughtful engagement indicates its own form of success. Recalling previously discussed approaches to evaluating speculative design, rather than defining success by whether or not the intentions of the designer were met – or if we were able to directly support citizen action – our case of public engagement might be best described as an experiment in cosmopolitics (cf. Stengers 2010), where again we might look for resonance in meaning among participants rather than an attempt to make a common present, or future. But mostly, I consider the methodological value and validity of this work to be its capacity for what Haraway (2016) calls ‘staying with the trouble’ – for creating and inhabiting spaces ‘without guarantees or the expectation of harmony with those who are not oneself’ (p. 98).

The Counting Sheep: NZ Merino in an Internet of Things (2011–2014) research project was generously supported by the Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund.

Alsop, P., Stewart, G. and Bramford, D. (2012). Selling the Dream: The Art of Early New Zealand Tourism. Nelson: Craig Potton Publishing.

Atwood, M. (2011). In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination. New York: Doubleday.

DiSalvo, C. (2012). Adversarial Design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dunne, A. and Raby, F. (2001). Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects. Berlin: Birkhauser.

Dunne, A. and Raby, F. (2013). Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Galloway, A. (2010). Mobile publics and issues-based art and design. In B. Crow, M. Longford and K. Sawchuck (Eds.) The Wireless Spectrum: The Politics, Practices, and Poetics of Mobile Media (pp. 63–76). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Haraway, D. (2008). When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Lather, P. (1993). Fertile obsession: validity after poststructuralism. Sociological Quarterly, 34(4): 673–693.

327

Le Guin, U. K. (2009). The critics, the monsters, and the fantasists. In Cheek by Jowl: Talks & Essays on How & Why Fantasy Matters (pp. 25–42). Seattle: Aqueduct Press.

Malpass, M. (2017). Critical Design in Context: History, Theory and Practices. London: Bloomsbury.

Michael, M. (2012). ‘What are we busy doing?’: engaging the idiot. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 37(5): 528–554. doi: 10.1177/0162243911428624

Stengers, I. (2010). Cosmopolitics I & II. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.