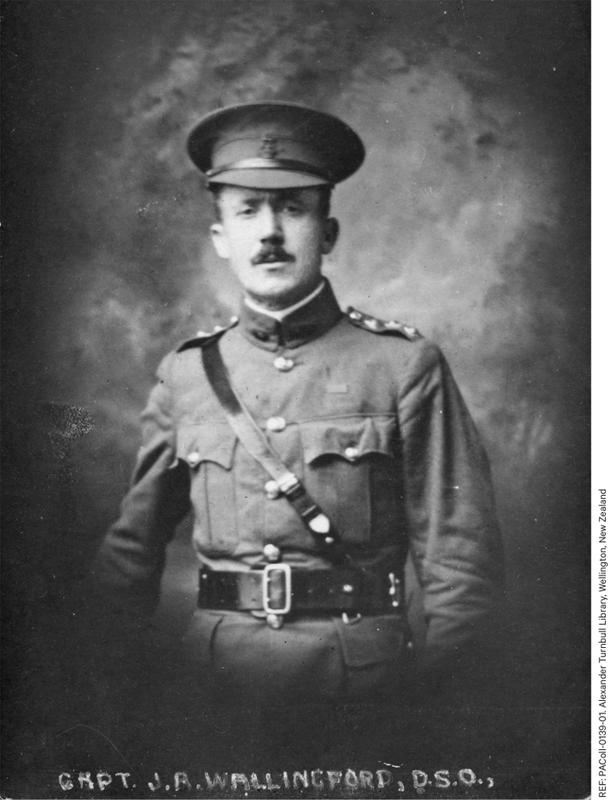

Captain Jesse Wallingford — a ‘prince of riflemen’, the ‘king of sharpshooters’, the ‘human machine-gun’ or, as Ormond Burton called him, ‘the hero of Anzac’ — was one of the outstanding figures in the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) at Gallipoli.1 While the records of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) contain surprisingly few references to Wallingford, he features prominently in soldiers’ writings and in New Zealand histories. One soldier wrote that Wallingford was ‘the most valuable man in the Expeditionary Force; a man for whom no military honour or decoration would be undeserved’.2 Another commented that he was ‘the greatest hero in the N.Z. forces. He won the Military Cross and he ought to have a dozen Victoria Crosses besides.’3 A poem in a New Zealand newspaper in December 1915 highlights Wallingford’s status:

‘Snipe’ Wallingford’s really a wonder;

And any Turk, loitering under

The gaze and the gun

Of this eagle-eyed one,

Will find he has made quite a blunder.4

Although only a captain, Wallingford had a significant impact on the course of the Gallipoli campaign through the positions he held; his character, bravery and expertise; and, most importantly, because of the small scale of the campaign and the fact that the survival of the beachhead at Anzac Cove was dependent on holding a few key positions, such as Quinn’s Post.

Jesse Wallingford was born in England in 1872. His father was a non-commissioned officer (NCO) in the British Army’s Rifle Brigade and a noted marksman. Wallingford entered the Rifle Brigade as a boy soldier, aged 14; within a few years he began to establish a reputation as an outstanding shot with the rifle and later the pistol. Between 1894 and 1907, he was champion shot of the British Army on six occasions. Wallingford won numerous other shooting competitions, as well as a bronze medal at the London Olympics in 1908. He was especially renowned for the rapidity and accuracy of his shooting with standard service rifles. Wallingford spent much of his career as an instructor at the School of Musketry, Hythe; in addition to teaching musketry, he was involved in a range of small-arms experiments and became an expert in the use of machine guns.5

In 1903 he became a warrant officer, and two years later he was recommended for a commission in the British Army, but was not granted one; a decision that appears to have rankled. Late in 1910 he applied for a commission in the newly formed New Zealand Staff Corps. The commandant of the School of Musketry recommended Wallingford to the New Zealand government, describing him as ‘a strong character’, who could be trusted and who had a positive impact on those around him. In 1911, Wallingford, his wife, Alice, and their three children arrived in New Zealand. He was commissioned as a lieutenant in the staff corps and posted to Auckland, where he first served as the district musketry instructor.6 Wallingford was one of a number of British Army personnel recruited to strengthen the regular New Zealand forces, which were being expanded to meet the demands of the new military organisation based on compulsory military training.7

As a marksman, Wallingford was renowned for his self-control and ability to maintain concentration.8 He was noted ‘as not being greatly troubled with nerves’. As a young soldier, one of his feats was to shoot a sixpence held between his brother’s thumb and finger.9 However, the first confidential report on Wallingford, prepared in March 1912, criticised aspects of his personality. The commanding officer of the Auckland Military District described him as having ‘an unpleasant and peevish temper. Strictly temperate habits — a teetotaller and non-smoker. His great hobby in life is shooting.’10 Nonetheless, within the New Zealand forces his views on musketry and machine-gun issues were highly respected.11 Wallingford had strong opinions about matters in which he had expertise, and was quite prepared to express his views frankly. This trait created some difficulties.12 Although he appears to have had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances, Wallingford was something of an outsider in the New Zealand forces. In a letter to his wife, he remarked that ‘my face was a little too hard [impudent] for’ Aucklanders who were too inclined to ‘accept anybody at their face value’.13

By April 1915, Wallingford was 43 years old and serving as the machine-gun officer of the New Zealand Infantry Brigade (NZIB), which was part of Major General Sir Alexander Godley’s New Zealand and Australian Division. Godley had a good understanding of machine guns and had arranged for each of the NZEF’s infantry battalions to have four, rather than the standard two. This substantially increased the brigade’s firepower. Godley also pioneered the appointment of specialist machine-gun officers, which only took hold in the British Army from mid-1915.14

Wallingford valued character and expertise above rank or background. This was evident on Gallipoli, where he had a close and rather informal relationship with his élite group of scouts and with other enlisted men whom he held in high regard.15 At the Apex in August 1915, Wallingford took the unusual step for an officer of discussing a difficult position with his men. They ‘unanimously decided to hold on and fight no matter what happened’.16 Wallingford had a particularly close relationship with the outstanding scout Private Colin Warden, an Australian serving in the Auckland Battalion. Within a few days of the landing, Wallingford ‘decided Warden was a brilliant soldier and cultivated his acquaintance until he not only became my personal scout but also a very dear comrade’.17 Warden held Wallingford in high regard, and another soldier described their relationship as being ‘more like brothers than officer and scout’.18

On 25 to 26 April 1915, Wallingford first had a major impact at Gallipoli. When he temporarily took command of the NZIB on the morning of the landing Brigadier General Harold ‘Hooky’ Walker decided that the brigade’s machine guns would revert to the control of battalions. This left Wallingford as an additional staff officer at brigade headquarters.19

At about 8 p.m. on 25 April, Walker ordered Wallingford to guide two newly arrived companies of the Canterbury Battalion up a spur which quickly became known as Walker’s Ridge.20 This ridge, on the left flank of the Anzac beachhead, led up to a long narrow plateau running southwest that later became known as Russell’s Top. If these positions were lost, the beachhead would become untenable.21 When he reached the base of Walker’s Ridge, Wallingford discovered that Lieutenant Colonel George Braund, the commanding officer of the 2nd Australian Battalion, who had been leading the defence of the area since the morning, had, along with most of his men, ‘evacuated the position’ and that the ‘whole of our left flank is exposed except for a small piquet near the sea’.

Wallingford decided that extraordinary steps were necessary and, in the darkness, impersonated Walker. He ordered the exhausted Braund to move back up the ridge, and at the same time encouraged him by explaining that he had brought substantial reinforcements, as well as desperately needed entrenching tools. Braund did as he was ordered, but Wallingford still had to go up the ridge gathering men, until he reached Russell’s Top. Having posted men to secure the front line, Wallingford then sent 20 more to reinforce the piquet by the sea. Wallingford returned to Walker’s headquarters at about 3.30 a.m. and informed him that the flank was secure.22

The following day, Walker received a report that the troops on Walker’s Ridge lacked leaders and were badly disorganised. Wallingford volunteered to do what he could to stabilise the situation. On the ridge, he found a mob of exhausted men who were lying down, being picked off by snipers and not returning fire. Wallingford could see that some men were slipping away. A degree of panic was caused by confusing and disturbing orders, and calls for stretcher bearers that were passed down the ridge. Wallingford called out that he was now in command, that no more alarming orders were to be shouted, that the wounded were to lie where they were, and that he would ‘blow out the brains of the next German spy that passed an order’.

Shortly afterwards a man in an Australian uniform ran down the ridge, calling on the Anzacs to retire as the Turks were attacking. Wallingford ‘could not see through the scrub so as to shoot him myself so hollered out “shoot that B— he must be a German”’. The man was then apparently shot. It was clear to Wallingford that his men would flee unless he took decisive action. He later recalled how he had been taught that ‘to advance is to win’, and quickly decided that a counter-charge was the best way to head off a crisis. He ordered his troops to ‘fix bayonets and let’s fight it out like men’, and then jumped to his feet and charged. Initially only a few men, perhaps two, followed him up the ridge, but others soon joined them.23 The Turks melted away in front of them, but they were met by a ‘dreadful fire; men going down all around’.24

After advancing about 25 metres, Wallingford was surprised to come across two of the Wellington Battalion’s machine guns with their crews lying dead or wounded around them. With the assistance of one young gunner, Wallingford quickly repaired a machine gun and used it with great effect, beating off three frontal attacks by Ottoman troops as well as efforts to work around the flanks. In addition to inflicting many casualties with the machine gun, Wallingford used a rifle to dispatch several snipers. The renewed firing of the machine gun attracted the attention of men behind Wallingford and they filtered forward in ones and twos.

By about 5 p.m., Wallingford had enough men to crew both machine guns and to properly hold his position. He then returned to Walker’s headquarters.25 Wallingford’s courageous actions on Walker’s Ridge were vital to retaining an area of the utmost tactical importance. He was awarded the Military Cross, the citation for which stated: ‘On the 25th and 26th April, 1915, during operations near Gaba Tepe, for exceptionally good services with the New Zealand Brigade machine-gun and sharpshooters, and for conspicuous coolness and resource on several critical occasions.’26 Wallingford’s first thought when he learnt of the award was ‘what will Sid [his son Sidney] think of it and what will his school chums say when he goes to [Auckland] Grammar the morning it appears in the Herald’.27 Wallingford thought that he deserved a higher honour, telling his son that in half an hour on Walker’s Ridge he had ‘earned the DSO easily’.28

Although he was highly experienced, Wallingford appears to have not been on active service before he landed at Gallipoli, and he relished the prospect of action. After elements of the NZEF were deployed to defend the Suez Canal early in 1915, he told a colleague that ‘I haven’t had any fun but live in hopes’.29 On 24 April, the cheering, martial music and excitement amongst the Allied troops assembled in Mudros harbour had a great impact on him. He told his son that ‘the cheering was so tremendous as to carry one quite away. Home, Wife and Kiddies are forgotten — it is now simply a desire to get at the enemy.’30

For a man who had never seen combat, Wallingford’s initial diary entries are rather matter-of-fact. The reality was, however, somewhat different. He was no unthinking hero, and later admitted that as he led the Australians up Walker’s Ridge he was terrified ‘every step up that ridge but was determined to carry out the job’.31 He also confessed that a day later he had to summon up his courage before leading the counter-charge. As he told a reporter, having made the decision to charge, ‘a tug-of-war commenced in his own mind. He could not make up his mind to get up and start, for, after all, they were more or less under cover on the ground. All sorts of arguments passed through his mind’, including that a British officer had to be ready to face death. He thought: ‘It is almost thirty years now that you have been kept by the State. Now, then, pay the price! Then I thought to myself that I was a coward, but that didn’t get me up. Then I thought of what my boy would think of me, and I was up like a shot, calling the men to charge.’32

At the centre of Wallingford’s recollection was relief that he had overcome his fears and performed useful service.33 In April, he was extremely critical of the exhausted Australians holding Walker’s Ridge, writing: ‘Australians jumpy and their Col — dam his soul — is dreadfully so … Col B[raund] is brave but oh such an old woman. He talks such utter rot that makes all his men jumpy.’34 Conversely, Wallingford had a high regard for the competence and personal qualities of Lieutenant Colonel William Malone, whose Wellington Battalion replaced the Australians on Walker’s Ridge. He was impressed by the way Malone quickly assessed the dangerous situation on the ridge and ‘pulled things straight’.35

Wallingford was not always a harsh critic of those who might be seen to have failed the initial test of combat. On 26 April he encountered Major Robert Bayly of the Auckland Infantry Battalion, with which Wallingford had begun his war service. Bayly was very pleased to meet Wallingford, greeting him with a friendly ‘What Ho Wal’, and freely admitted that he and his company had fled when they encountered the Turks. At the time of their meeting, Bayly was in the process of trying to locate his company. Such a state of affairs would be expected to have offended Wallingford’s professional sensibilities, but he passed over Bayly’s performance without comment. Wallingford’s stance can perhaps be explained by his personal relationship with Bayly and by Bayly’s death in action before Wallingford wrote his account; however, Braund met the same fate and was not spared.36

The second occasion on which Wallingford had a significant impact was during May and June, when the Allied troops were on the defensive. Once the situation at Anzac Cove stabilised, the machine guns of the New Zealand and Australian Division were again brigaded, with Wallingford taking charge of the NZIB’s guns, and Captain John Rose the guns of the 4th Australian Brigade. When the NZIB went south to Krithia on 5 May, Wallingford remained at Anzac Cove with half the machine guns and was, it appears, given overall command of the machine guns in the northern half of the Anzac front line, which was the responsibility of the New Zealand and Australian Division.37 The NZIB was temporarily replaced by units from the Royal Naval Division. Wallingford thought that these men were ‘useless’, and used the freedom of action his position gave him to ‘prowl about at all times, curse them into fighting instead of sitting at the bottom of the trench’.38

With the assistance of Captain Rose, Wallingford ensured that the key points in the New Zealand and Australian Division’s sector — Pope’s Hill, Quinn’s Post and Courtney’s Post — were protected by enfilading fire from multiple machine guns. These expertly placed guns devastated the attacks by Ottoman infantry on 19 May.39 During these attacks, Wallingford was at Quinn’s Post. It was, he noted, ‘a splendid scrap’. His last act, which ended four hours of fighting, was ‘simply cutting down a line of Turks who are charging. Awful.’40

Wallingford also used indirect fire to target Ottoman troops in areas they generally regarded as being safe. He carefully assessed the tactical and technical aspects of both the employment of machine guns and sniping, and was happy to change his views as a result of his operational experience.41 Wallingford’s emphasis on expanding the strength of machine-gun sections so that they could be more mobile and robust, on the use of alternative and concealed emplacements, on the importance of enfilading fire and other matters, all point to his being at the cutting edge of British Army thinking. This was evident in his actions and in his writings, especially the notes he sent to a former School of Musketry colleague.42

Godley was very pleased with the performance of his machine-gun officers: Wallingford, Rose and Captain Peter Henderson. Early in June he wrote that they ‘have been worth their weight in gold, especially Wallingford, who is one of the pluckiest and most energetic fellows I have ever seen. Rose, even though rather severely wounded in the arm, refused to go sick and fought his machine guns for weeks with his arm in a sling.’43 The outstanding record of the New Zealand machine guns during the First World War owes a great deal to the work of Wallingford, Rose and Henderson.44

Wallingford’s other major contribution was in organising sniping. Since the landing, Ottoman snipers had inflicted many casualties on the Anzacs. Early in May, at Godley’s direction, Wallingford selected 50 marksmen, organised into two watches of 25 men, who were then deployed where enemy snipers were most active. Wallingford was a skilled scout, and his snipers also acted as scouts and collected useful intelligence. Over the next few weeks, sniper teams were organised by other units and greatly reduced the number of Anzac casualties, as well as causing significant losses to the Ottoman forces.45

Wallingford did a substantial amount of sniping himself. On the twenty-second day of the campaign, he noted that it was the first day on which he had not killed any of the enemy and that he ‘had a very good bag up to date both with rifle and Maxim [machine gun]’.46 Wallingford kept a tally of his successes in a notebook nicknamed ‘the diary of death’.47 Whenever his other duties permitted, Wallingford would go out, generally with one of his scouts, ‘for a few hours’ killing’. His exploits soon became well known amongst the Anzac troops and, through soldiers’ letters, word soon spread to Australia and New Zealand. He decided he was best employed dealing with crack enemy snipers. On some occasions, Wallingford would use a machine gun in a masterly fashion against a particular target such as an enemy sniper, officer or machine-gunner.48 His successes were acclaimed by his comrades. One soldier who served with Wallingford later wrote:

I have seen him snipe with a machine gun, what a good sniper couldn’t get with the rifle. A sniper would tell him he couldn’t catch a Turkish sniper; Wallingford would get directions of the sniper’s whereabouts — with either machine gun or rifle he would have that sniper — the machine gun would speak, bur-r-r-r-r- Wallingford would say ‘poor chap’ and pass along the trench.49

Wallingford enjoyed great success against enemy snipers, but came close to being killed on at least one occasion and had considerable respect for his opponents.50 What is clear during this period was that Wallingford prided himself on having a detached, professional approach. The only occasion he ‘gloated over the killing’ was after he was enraged by what he regarded as a war crime.51

Wallingford was well aware of the role luck played.52 He certainly feared death or injury, and made no secret of this when writing to his family. In July, after telling his son that Captain Peter Henderson, the Mounted Rifles Brigade’s machine-gun officer, had been badly wounded, he wrote: ‘I haven’t got it yet but I fear it will come … God grant that I will get a soft one.’53 Like other soldiers, Wallingford developed a range of strategies, including a degree of fatalism, to cope with the stresses of combat.54 Although he was prepared to place himself in great danger, Wallingford carefully assessed the risks posed by any course of action. One of his élite scouts, for instance, suggested that he accompany him on an expedition lasting four days around the enemy lines. Wallingford told his wife that: ‘I ban myself going, although I do some funny tricks I still have an awful longing to hug a girl in Auckland and four days among the Turks is not conducive to appease [sic] my longing’.55 Nonetheless, he successfully masked any doubts from those around him. Corporal Charles Saunders DCM, a New Zealand sapper who worked closely with him developing defences on Walker’s Ridge during April and May, wrote that:

Wallingford was a wonderful man, and I don’t talk from hearsay but from what I saw. I worked with him and under him for a long time, and he amazed me with his courage and coolness … He was the strongest, most capable, coolest officer on Walker’s Ridge for at least the first three weeks and I don’t exaggerate when I say that, not only would I have followed him anywhere, but I’d have gone in front of him if he had asked me.56

Weeks of constant activity, which took him over much of the Anzac beachhead, took their toll on Wallingford; he became increasingly ill, and on 19 June was evacuated sick to Egypt.57

Wallingford returned to Gallipoli in time for the August Offensive, the last occasion on which he would have a significant impact on the campaign. It was initially decided that battalions would control their own machine guns. Consequently, Wallingford again served as an additional staff officer in the headquarters of Brigadier General Earl Johnston’s NZIB. On the morning of 7 August 1915, the NZIB found itself at the Apex, an area at least partially sheltered from Ottoman fire, at the intersection of Rhododendron and Cheshire ridges. The Apex was about 500 metres from the brigade’s objective, Chunuk Bair on the Sari Bair range.

At Godley’s insistence, Johnston ordered the Auckland Infantry Battalion to attack across the 60-metre-wide spur that linked the Apex with Chunuk Bair. It was apparent to Wallingford and other officers present that this was an almost suicidal proposition. Wallingford asked Johnston to delay the attack for a few minutes until he had several machine guns in a position to support it. His request was supported by the commander of the Auckland Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Young. Johnston, who, according to Wallingford, had always ‘treated me like a dog’, responded by shouting ‘stand back, I will deal with you later’. Johnston may have been drunk, but he was in any case incapable of properly commanding his brigade. After this rebuff, Wallingford’s friend Major Sammy Grant, the second-in-command of the Auckland Battalion, implored him to bring up the machine guns to provide covering fire. Wallingford responded by saying that:

I was not in command of them but that I had sent down for them and they would be here in a moment if he would only delay the advance for a few minutes. Just then the Brig gave the order ‘get away’ but they [the Auckland Battalion] would not move on … Sammy Grant shouted Good God they are refusing to advance, and shouted to me ‘Wally for Christ’s sake get the guns up[’], ran forward through the men and took them with him over the crest.58

The spur up which the Aucklanders attacked was so narrow that they had to advance in echelon. They were met by a storm of fire and only managed to advance a maximum of about 100 metres at a cost of some 300 men killed or wounded. Major Grant was mortally wounded and lay out on the spur all day in agony. Later Wallingford wrote that shortly after the failed attack, ‘the Brigadier came to me with tears streaming down his face and shouted “Wallingford can’t you help me”, I said of course I bloody well can if you will let me’. Johnston then agreed to all the machine guns being brigaded and placed under Wallingford’s command.59 Wallingford then placed the guns on the Apex to protect this vital position and provide support for a further attack on Chunuk Bair.

In the early hours of 8 August, Chunuk Bair was captured by William Malone’s Wellington Battalion and supporting British units. As previously agreed with Malone, Wallingford then sent machine guns forward to help with the defence of the crest and employed the remaining guns at the Apex in an effort, which initially met with some success, to limit enemy fire from other positions on the Sari Bair Ridge.60 The decision not to send the machine guns forward with the assault troops has recently been criticised, but it was tactically sound and in keeping with best practice.61 Intense fire was directed at the New Zealand machine guns at the Apex. Wallingford’s friend and scout, Private Colin Warden, was killed along with most of the men in a Maori Contingent machine-gun crew of which he had taken command.

The New Zealanders on the crest of the Sari Bair range were replaced on the evening of 9 August by fresh British troops, but the New Zealand machine guns remained. Early on 10 August a large Ottoman force swept down on the British garrison on Chunuk Bair, destroying the two battalions there, including seven machine guns and their crews (four New Zealand and three British), and causing a third battalion which was in reserve to flee in panic.62 Wallingford and his men had a low opinion of the British troops who had garrisoned Chunuk Bair. One of his scouts described the 5th Wiltshires as ‘simply awful … like sheep’.63 Chunuk Bair had been lost, Wallingford believed, because the Wiltshires had panicked when the Ottomans attacked, ‘bolting’ across the line of fire of the machine guns and thereby enabling the enemy to close in and push home their assault with bomb and bayonet.64

The first Wallingford knew of the counter-attack was when one of his men called out ‘Good God, look’. Wallingford looked up and ‘saw such as sight as I had seen in dreams. The enemy were coming down the slope in a huge counter-attack. We saw them, each line, coming over the top. They were in perfect lines of about 150 men a pace apart and about 15 yards distance not running and not walking just an amble.’

Wallingford had just finished repairing a gun. He selected a piece of ground over which the Ottomans must advance and, when they reached it, cut down half a line of men. The other nine machine guns joined in, creating an enfiladed area that Wallingford described as a ‘zone of death’ in which the Turks suffered devastating losses. He later told his son that after the initial three lines, all the attacking troops ‘go down. Some in their tracks others onto their knees and others get through but [the] guns follow them and they are no more. Poor beggars and gallant soldiers.’ Allied artillery then joined in, although Wallingford and others present were sure that most of the casualties were inflicted by the machine guns at the Apex.65 The enemy attack was smashed, and the Allied hold on the Apex maintained.

Wallingford took great pride in the vital part he and his men had played. He also took considerable satisfaction from the fact that his insistence that the machine guns should always be clean and ready for action meant that all of the guns at the Apex were able to engage the enemy.66 A small enemy force was spotted later in the day creeping into the Apex. Wallingford responded decisively to this threat by leading an impromptu counter-attack during which he killed several of the enemy at close range.

Late on 10 August, Brigadier General Travers and fresh British troops took over the Apex. Wallingford and his machine-gunners remained, and he would later describe the next 24 hours as the most difficult of his service at Gallipoli. He appears to have played a key part in organising the disposition of the new troops. The Apex was attacked and subjected to enemy fire during the night of 10–11 August, but the most dangerous problems had little to do with enemy action. Nervous troops fired randomly, but, much more dangerously, one party mistook some of their comrades for the enemy and attacked them. This started a panic amongst some of the inexperienced and poorly trained British troops, who began to flee through the New Zealand machine-gun positions, making it impossible for them to fire.

Wallingford was determined to stop any repetition. Once order had been restored, he ordered his gunners to fire on any approaching troops and concluded that there was ‘no hope for the troops in front if they retire. They must fight it out on their own ground.’ He spoke loudly so that the British troops in the vicinity could clearly hear him. Wallingford then quietly instructed his gunners to fire over the heads of any fleeing British soldiers. Shortly before dawn on 11 August, the New Zealand machine gunners were obliged to do this when British troops began to flee after seeing Ottoman forces apparently massing for an attack.67

After the August Offensive, it was rumoured that the New Zealand machine guns had fired into fleeing British ‘New Army’ troops, and that this was why Wallingford had been sent home. The Defence Minister, James Allen, wrote to Wallingford, asking him to respond.68 Wallingford’s reply was rather brief and evasive. He praised the work of his gunners, and concluded by stating that he was ‘supposed by the Returned Soldiers to be in disgrace: but, knowing that I did my duty I think it best to take no notice of old soldiers[’] tales. Believe me in that I am not complaining — WE MUST WIN THIS WAR and let the controversy take place afterwards.’69

Allen was determined to get to the bottom of the matter and asked Wallingford to specifically address the allegation that New Zealand machine guns had fired on British troops.70 Wallingford reluctantly responded with a detailed account, ‘24 Hours with Green Troops’, which he asked the minister to keep secret.71 The description of Wallingford’s actions set out above is based on this account. It seems significant that Wallingford, who normally expressed himself in a definite, direct way, wrote, after describing his orders to his men to fire over the heads of any fleeing British soldiers, that ‘this I understand was done’.

This piece of prevarication can perhaps be explained by Wallingford’s desire to see further active service and an understandable fear that admitting that he had had his machine guns fire on British troops would scuttle these hopes. Wallingford’s conduct during the campaign, especially during the August Offensive, suggests that if he felt it necessary he would not have hesitated to fire on fleeing friendly troops. Such drastic action was certainly not unknown during the First World War.72 There is good evidence that the New Zealanders at the Apex did fire on panic-stricken British troops. Writing after the war, Colonel (later Major General) Arthur Temperley, who had been the Brigade Major of the NZIB, stated in his unpublished ‘A Personal Narrative of the Battle of Chunuk Bair August 6–10th 1915’ that on 10 August the ‘lack of training and steadiness’ of the inexperienced British units caused him ‘grave anxiety at times’. He then went on to state that:

The morale of some of the New Army battalions decreased very rapidly. It is with deep regret that I must set down the fact that on August 10th I saw 300 or 400 of them running forward to the Turks with their hands up. To save a disaster of the first magnitude and prevent the whole front collapsing I gave orders to the machine guns of our Brigade to open fire upon them and at some cost in lives the movement was checked and they ran back to their lines.73

Even the account Wallingford gave to Allen makes it clear that harsh measures were required at the Apex to ensure that the Allied line held. Wallingford was clearly shocked by his experiences during the night. At one point, while unsuccessfully trying to get volunteers to carry stretchers forward for the wounded, he found a group of men ‘on their knees with their heads in the bottom of the trench’, which was only about half a metre deep. Wallingford then proceeded to chastise them with a leather strap from a stretcher. The men went forward and brought back some wounded, but then disappeared with the stretchers, forcing Wallingford and one of his men to drag wounded men who were ‘screaming with pain’ to safety. Later during the night he stood at the end of a trench and threatened to shoot any man withdrawing past him:

Almost immediately a poor devil came along from the front … crying bitterly. I grabbed him [at] which he sat down on the ground. He was simply frightened so I threatened to shoot him if he didn’t get up. He refused so I let off a shot from my revolver into the ground close to his buttocks. This seemed to have splashed [ricocheted], anyway it made him jump to his feet.

Wallingford later recalled hearing ‘the murmur that went along the line — “he has shot him” — it seemed to do the trick for I could then do anything with them’.74

Professional pride features prominently in Wallingford’s description of his actions during the August Offensive. He was proud that he had again proved he could stand up to the stresses of combat. Describing an incident in which he foiled a dangerous Ottoman move against the Apex, he wrote: ‘I had always wondered if I would be shaky with the pistol. Now just after it was over I was terribly excited knowing that I had led a charge, but during the actual killing (pressing the trigger) I was fairly quick but terribly deliberate and sure of getting my man.’75

There is, however, some evidence that the novelty of shooting at live targets was wearing off. Early in the offensive, Wallingford shot a large number of confused Turks with rifles and then had his machine guns ‘clean them up. It was murder pure and simple but it was war.’76 Later, in a letter to his parents in which he described shooting three enemy scouts with a pistol at ranges between 30 centimetres and 18 metres, Wallingford wrote that the men were ‘Poor devils! All youngsters.’77 Responding to remarks in a letter by Wallingford, a writer in the Thames Star at the end of September 1915 commented that if he was becoming ‘sick of killing. We don’t wonder at it. He possibly has more Turks to bag than any other soldier, officer, non-commissioned officer, or private, on the Peninsula.’78

Under the pressure of intense combat during the August Offensive and his rage at the deaths of his friends Colin Warden and Sammy Grant, Wallingford’s persona as a cool, professional soldier fell away and was for a time replaced in part by a visceral lust for revenge. After the useless sacrifice of the Auckland Battalion, Wallingford was beside himself with fury. He later admitted that he went ‘berserk’ and was tempted to shoot Johnston.79 It was, however, the death of his friend Colin Warden that finally led to Wallingford losing a degree of control. Warden’s death was to Wallingford ‘more than the loss of a brave scout[,] it was a catastrophe over which I never recovered. He was the bravest of the brave, would go anywhere and do anything[,] was a most intelligent and entertaining man.’80 Warden’s death led Wallingford ‘to fight like a devil for the following 7 or 8 days and nights. I spared nothing and on looking back I seem to see a fiend after blood.’81 Although he may have become for a period ‘a Berserker’, Wallingford was a very cool and calculating one, and was all the more deadly as a result.82

Like Lieutenant Colonel William Malone, with whom he had much in common, Wallingford believed strongly in the nobility of being killed while fighting bravely for your country. This belief was of some comfort to him after the death of Colin Warden.83 In his account of the August fighting, Wallingford made insightful remarks on a range of matters. He noted, for example, that during heavy combat time seemed to stretch out.84

During the August Offensive, the extent to which Wallingford valued professional competence and courage was again evident. He was as happy to praise these qualities in a private as in a senior officer. Poorly trained, ineffective soldiers, such as the newly raised battalions of Kitchener’s Army, were dismissed by Wallingford as ‘troops who … could not fight enough to keep themselves warm’. Substandard troops offended Wallingford’s sense of professionalism, but his real contempt and loathing were reserved for incompetent officers. He described one British battalion commander as an ‘old fossil’ who ‘knew no more of m[achine] g[un] tactics than a pig’.85

Wallingford thought well of Walker, but regarded his brigadier Earl Johnston as an incompetent, weak man who was unfit for command. Johnston’s arrogant and dismissive attitude towards Wallingford and his professional expertise was especially hurtful to him. After the end of the campaign, Wallingford commented that he had been ‘thankful for every hour of the training I have received since I became a soldier. Every scrap of practice with rifle, revolver, and machine-gun has all been useful.’86

Wallingford was feeling the stress of hard service, and his health finally collapsed late in August. He was evacuated from the peninsula and was never to see action again. When he was initially evacuated from Gallipoli, Wallingford was diagnosed as suffering from neurasthenia, a form of war neurosis brought on by prolonged and intense physical or psychological stress. The symptoms of this disorder included chronic fatigue and headache. Later, however, his diagnosis was changed to ‘heart strain’.87

After a period of treatment in England, Wallingford returned to New Zealand early in 1916. He was keen to see further active service. Although at one point Wallingford was passed fit, his health prevented this, and he spent the rest of the war on instructional and staff duties in New Zealand. His health problems at this time may have been mental as well as physical, as in 1917 Godley wrote to the commander of the New Zealand forces that he was ‘much amused by what you say about Wallingford. I quite agree with you that his head is about as dicky [not healthy] as his heart’. Wallingford was bitter after his return to New Zealand at being passed over for promotion and at the lack of medallic recognition given to his machine-gunners for their role in the August Offensive. Wallingford was made a substantive captain in the New Zealand Staff Corps in June 1916, and was finally discharged from the NZEF on 30 April 1917.88 He retired from the New Zealand Staff Corps as a major in 1927. Between 1929 and 1941, Wallingford was superintendent of the Ranfurly Veterans’ Home in Mount Roskill. He died in 1944.89 Up until his death, Wallingford enjoyed good health and did not appear to have any ‘lasting mental scars’ from his war service.90

As a sniper and machine-gunner, Wallingford was directly responsible for many more deaths than the vast majority of soldiers. There is a tendency for soldiers to pass over as much as practicable the blood they have on their hands, but Wallingford did not. He noted the casualties he had inflicted in a detached way, which is consistent with his view of how a professional soldier should behave. Central to Wallingford’s conception of his experience at Gallipoli was the validation of his status as a professional soldier, able to do his duty and perform well under the stresses and strains of war. Nonetheless, it is evident that during the August Offensive, Wallingford became something of ‘a fiend’, intent on avenging his dead friends. The way he candidly analysed his thought processes and feelings and shared them with his wife and son in his letters home is especially interesting. He may have appeared as a nerveless heroic figure to those who served with or under him, but his own writing reveals a more typical mix of emotions and concerns. The collapse of his health as a result of his service at Gallipoli is clear evidence of the physical and mental toll the campaign took.

Notes

1 J. L. Sleeman, ‘A Prince of Riflemen: The “Mad Minute” and the “Old Contemptibles”’, Chambers’s Journal, 1 August 1924, p. 504; Lyttelton Times, 28 September 1915, p. 6; Taranaki Daily News, 8 January 1916, p. 3; O. E. Burton, The Silent Division: New Zealanders at the Front: 1914–1919 and One Man’s War (Christchurch, John Douglas, 2014), p. 294.

2 Dominion, Wellington, 24 November 1915, p. 6; Wallingford is, for example, referred to on 40 pages of Richard Stowers, Bloody Gallipoli: The New Zealanders’ Story (Auckland, David Bateman, 2005).

3 Correspondence: Edwin Honnor to Mother, 9 September 1915, quoted in Glyn Harper (ed.), Letters from Gallipoli: New Zealand Soldiers Write Home (Auckland, Auckland University Press, 2011), p. 178.

4 Free Lance, Wellington, 17 December 1915, p. 18.

5 ‘Known as the “Boy Shot”: Sergt. Wallingford tells of his Feats’, Chums, 1 May 1901, pp. 583–4; Sleeman, op. cit., pp. 505–7; ‘Jesse Wallingford’, Athletes, retrieved 1 April 2014, http://www.sports-reference.com/olympics/athletes/wa/jesse-wallingford-1.html.

6 Military Personnel File: Jesse Wallingford, Congreve to New Zealand High Commissioner, 22 December 1910, Hall Jones to acting Prime Minister, 20 April 1911 and related papers, AABK W5586, 0136689, Archives New Zealand, Wellington (hereafter ANZ); Sleeman, op. cit., p. 505; ‘Army Rifle Champions: Successful Marksmen of the Sixty Shot’, The Navy and Army, 21 July 1906, p. 138; Herbert A. Jones, The ABC of the Rifle (London, Henry J. Drane, 1903), pp. 99–103; Thames Star (hereafter TS), 30 September 1915, p. 4.

7 Peter Cooke and John Crawford, The Territorials: The History of the Territorial and Volunteer Forces of New Zealand (Auckland, Random House, 2011), pp. 162–3.

8 Sleeman, op. cit., p. 505; Correspondence: Geoffrey Wallingford to author, 8 July 2014.

9 ‘Known as the “Boy Shot”’, op. cit., p. 583.

10 Military Personnel File: Jesse Wallingford, Annual Confidential Report, 31 March 1912, NZDF Archives, Trentham (hereafter NZDFA).

11 Correspondence: Adams to Gibbon, 10 May 1916, AD1 43/220, ANZ; Military Personnel File: Jesse Wallingford, Note by Godley, Annual Confidential Report for 1912–13, 9 May 1913, NZDFA.

12 Correspondence: Chaytor to Headquarters New Zealand Military Forces, 8 March 1913, Wallingford to General Staff Officer Auckland, 10 March 1913 and related papers, AD1 98/6, ANZ; Correspondence: Wallingford to Wife, 17 May 1915 and Diary: Jesse Wallingford, Alexandria, 10 July 1915, Wallingford Family Collection, Wellington (hereafter WFC); There are essentially three surviving fragments of different versions of Wallingford’s wartime diary. It is unclear how much, if anything, of the diary may have been lost.

13 Correspondence: Wallingford to Wife, 17 May 1915, WFC; TS, 30 September 1915, p. 4.

14 Correspondence: Godley to Minister of Defence, 3 September 1914 and marginalia dated 7 September 1914, AD1 57/104, ANZ; G. S. Hutchinson, Machine Guns: Their History and Tactical Employment (being also a History of the Machine Gun Corps, 1916–1922) (London, Macmillan, 1938), pp. 139, 141.

15 Diary: C. W. Saunders, 9 May 1915, MS-Papers-7336-1, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington (hereafter ATL); Correspondence: Wallingford to Son, 11 July 1915, WFC.

16 Correspondence: Wallingford to Allen, 31 July 1916, MS-1088, Hocken Library, Dunedin (hereafter HL).

17 Correspondence: Wallingford to Harrowell, 1 November 1915, Descendants of the Warden Family, Australia (hereafter DWF).

18 Correspondence: Friend of Warden, no date, DWF.

19 Diary: Jesse Wallingford, 10 April to 26 June 1915, WFC; Memoir: Frederick Victor Senn, ‘Gallipoli Recollections’, MS-Papers-1697, ATL, pp. 3–4.

20 Diary: Jesse Wallingford, 10 April to 26 June 1915, WFC.

21 C. F. Aspinall-Oglander, Military Operations Gallipoli, Volume 1: Inception of the Campaign to May 1915 (London, Heinemann, 1936), pp. 167, 190; Chris Roberts, The Landing at Anzac 1915 (Canberra, Army History Unit, 2013), pp. 48–53.

22 Unpublished Typescript: Jesse Wallingford, ‘Gallipoli: The Following is Written Up after I have Refreshed My Memory from My Diary’, WFC. This typescript account is more detailed than the manuscript diary, but is consistent with it. In his letter to his son of 11 July 1915, Wallingford says that after Braund said he would not go back up the ridge, he said ‘I was acting for the General and he had to go back. I then showed him I had two companies to reinforce him. He eventually came back but I and the Scout Sgt had to examine every bush and every inch of ground.’ This version of events perhaps sounds more plausible than Wallingford impersonating Walker. But Wallingford’s later accounts of the incident are definite and consistent. The most likely explanation for the discrepancy is that Wallingford did not wish to own up to impersonating a senior officer in a letter that would be censored, but that after the war he felt free to write a more accurate account. See also O. E. Burton, The Auckland Regiment: Being the Doings on Active Service of the First, Second and Third Battalions of the Auckland Regiment (Wellington, Whitcombe and Tombs, 1922), p. 31.

23 Correspondence: Wallingford to Sidney Wallingford, 11 July 1915, WFC.

24 Unpublished Typescript: Jesse Wallingford, ‘Gallipoli’, op. cit.; Evening Post, Wellington (hereafter EP), 16 November 1915, p. 7.

25 Correspondence: Wallingford to Walker, 27 April 1915; Diary: Jesse Wallingford, Alexandria, 10 July 1915, WFC; Unpublished Typescript: Jesse Wallingford, ‘Gallipoli’, op. cit; Diary: Private J. R. Dunn, 27 April 1915, quoted in Pat White, Gallipoli: In Search of a Family Story (Masterton, Red Roofs, 2005), p. 40; Diary: William Malone, 27 April 1915, quoted in John Crawford with Peter Cooke (eds), No Better Death: The Great War Diaries and Letters of William G. Malone, 2nd edition, (Auckland, Exisle, 2014), pp. 164–7; EP, 16 November 1915, p. 7.

26 London Gazette (hereafter LG), no. 29215, 3 July 1915, p. 6541; Wallingford was also mentioned in dispatches for his service at Gallipoli. LG, no. 29251, 5 August 1915, p. 7669.

27 Correspondence: Wallingford to Sidney Wallingford, 11 July 1915, WFC.

28 Ibid.

29 Correspondence: Wallingford to Rose, 12 February 1915, WFC.

30 Correspondence: Wallingford to Sidney Wallingford, 11 July 1915, WFC.

31 Ibid.; Unpublished Typescript: Jesse Wallingford, ‘Gallipoli’, op. cit.; Correspondence: Wallingford to Allen, 31 July 1916, MS-1088, HL.

32 EP, 16 November 1915, p. 7; Correspondence: Wallingford to Sidney Wallingford, 11 July 1915, WFC.

33 Ibid.

34 Diary: Jesse Wallingford, 26 April 1915, WFC.

35 Order Book: Jesse Wallingford, 29 April 1915, WFC; Diary: Jesse Wallingford, Alexandria, 10 July 1915, WFC.

36 Correspondence: Wallingford to Sidney Wallingford, 11 July 1915, WFC.

37 NZ & A Division Report on Operations, 28 April – 5 May 1915, WAI 2 [1m], ANZ.

38 Diary: Jesse Wallingford, Alexandria, 10 July 1915, WFC, p. 7.

39 Christopher Pugsley, Gallipoli: The New Zealand Story (Auckland, Reed Books, 1998), pp. 222–6; Peter Stanley, Quinn’s Post: Anzac, Gallipoli (Crows Nest, Allen & Unwin, 2005), pp. 25–7, 62–6; Diary: Jesse Wallingford, Alexandria, 10 July 1915, WFC, p. 7.

40 Diary: Jesse Wallingford, ibid.

41 Correspondence: Wallingford to Headquarters D Section, no date, WFC; Unpublished Typescript: Jesse Wallingford, ‘Gallipoli’, op. cit., pp. 10–11; Notes: Jesse Wallingford, ‘Note from Dardanelles’, received by Oborn 2 August 1915, ‘Subterfuge’ and ‘Indirect Fire’, WFC.

42 Notes: Jesse Wallingford, ‘Note from Dardanelles’, ibid.; J. Bostock, The Machine Gunners Handbook including the Vickers Light Gun (London, WH Smith & Son, 1915), pp. 198–200, 258–78; Hutchinson, op. cit., pp. 119–42.

43 Correspondence: Godley to Heard, 5 June 1915, WA 252/6, ANZ.

44 J. H. Luxford, With the Machine Gunners in France and Palestine: The Official History of the New Zealand Machine Gun Corps in the Great War 1914–1918 (Auckland, Whitcombe and Tombs, 1923), pp. 15–19.

45 Diary: Hami Grace, 1–14 June 1915, Wellington College Archives, Wellington; Diary: Braithwaite, 26 May 1915, NZ & A Div Special Order, 25 May 1915, WA 21/24 [21a], ANZ; Diary: William Malone, 2 June 1915, quoted in No Better Death, op. cit., p. 225; Notes: Jesse Wallingford, ‘Note from Dardanelles’, op. cit.; Unpublished Typescript: Jesse Wallingford, ‘Gallipoli’, op. cit., pp. 9–10; New Zealand Herald, 8 December 1915, p. 8; C. E. W. Bean, The Story of Anzac: From 4 May, 1915, to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula (Sydney, Angus and Robertson, 1924), pp. 248–9, 285–7; Pugsley, op. cit., pp. 238–40.

46 EP, 24 July 1915, p. 6; Diary: Jesse Wallingford, Alexandria, op. cit., p. 7.

47 Sydney Morning Herald, 22 January 1916, p. 7.

48 Unpublished Typescript: Jesse Wallingford, ‘Gallipoli’, op. cit.; Press, Christchurch, 22 July 1915, p. 8; Argus, Melbourne, 12 July 1915, p. 7.

49 Diary: Saunders, op. cit., 9 May 1915, ATL.

50 Notes: Jesse Wallingford, ‘Note from Dardanelles’, op. cit.

51 Unpublished Typescript: Jesse Wallingford, ‘Gallipoli’, op. cit., p. 12; In the typescript memoir of his service at Gallipoli, Wallingford states that his feelings were prompted by the execution of Edith Cavell, but this is clearly incorrect as she was not executed until October 1915. It seems more likely that Wallingford was incensed by the sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915.

52 Correspondence: Wallingford to Sidney Wallingford, 11 July 1915, WFC; Unpublished Typescript: Jesse Wallingford, ‘Gallipoli’, op. cit., p. 5.

53 Correspondence, Wallingford to Sidney Wallingford, 11 July 1915, WFC.

54 Ibid.; Alex Watson, ‘Self-deception and Survival: Mental Coping Strategies on the Western Front, 1914–18’, Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 41, no. 2, 2006, pp. 251–3, 262–8.

55 Correspondence: Wallingford to Wife, 17 May 1915, WFC.

56 Diary: Saunders, op. cit., 9 May 1915.

57 Notes: Jesse Wallingford, 8–20 June 1915, WFC; Diary: Jesse Wallingford, Alexandria, 10 July 1915, WFC, p. 8.

58 Correspondence: Wallingford to Braithwaite, 29 June 1936.

59 Ibid.; Memoir: A. C. Temperley, ‘A Personal Narrative of the Battle of Chunuk Bair August 6–10th 1915’, 95/16/1, Imperial War Museum, London (hereafter IWM), p. 8; Pugsley, op cit., pp. 282–3.

60 Correspondence: Wallingford to Braithwaite, 29 June 1936; Memoir: Temperley, op. cit., pp. 16–17; Pugsley, op. cit., p. 285; Stowers, op. cit., pp. 166–7.

61 R. V. K. Applin, ‘Machine Gun Tactics in Our Own and other Armies’, Royal United Services Institution Journal, vol. 54, no. 1, 1910, pp. 48–9; No Better Death, op. cit., pp. 309, 315–16.

62 Correspondence: Wallingford to Braithwaite, 29 June 1936; Memoir: Temperley, op. cit.; Correspondence: Wallingford to Allen, 31 July 1916, op. cit.; War Diary: New Zealand Infantry Brigade, 10 August 1915, WA70/1, ANZ; Stowers, op. cit., p. 195.

63 Correspondence: Wallingford to Son, 6 September 1915, WFC.

64 Ibid.; Correspondence: Wallingford to Allen, 31 July 1916, op. cit.; Pugsley, op. cit., pp. 308–9.

65 Correspondence: Wallingford to Son, 6 September 1915, WFC; War Diary: New Zealand Infantry Brigade, op. cit.

66 Note: Jesse Wallingford, ‘Turks Counter Attack 10/viii/15’, WFC; Memoir: Temperley, op. cit., p. 23; Pugsley, op. cit., p. 309; Harvey Broadbent, ‘“No Room for Any Lapses in Concentration”: Ottoman Commanders’ Responses to the August Offensive’, in Ashley Ekins (ed.), Gallipoli: A Ridge Too Far (Wollombi, Exisle, 2013), p. 212.

67 Correspondence: Wallingford to Allen, 31 July 1916, op. cit.; Diary: Hugh Stewart, 9 August 1915, MS-Papers-9080-02, ATL.

68 Correspondence: Allen to Wallingford, 5 July 1916, MS-1088, HL.

69 Correspondence: Wallingford to Allen, 11 July 1916, MS-1088, HL.

70 Correspondence: Allen to Wallingford, 14 July 1916, MS-1088, HL.

71 Correspondence: Wallingford to Allen, 31 July 1916, MS-1088, HL.

72 Ibid.; Graham Seton, Footslogger: An Autobiography (London, Hutchinson, 1931), p. 214.

73 Memoir: Temperley, op. cit., p. 20.

74 Correspondence: Wallingford to Allen, 31 July 1916, op. cit.

75 Correspondence: Wallingford to Sidney Wallingford, 6 September 1915; Ashburton Guardian (hereafter AG), 25 September 1915, p. 5. The weapon Wallingford used, a .38 Webley Scott automatic pistol, was an uncommon one, which had been presented to him by the manufacturers in 1911. Correspondence: Sidney Wallingford to Editor National Rifle Association Journal (England), 20 July 1966, WFC.

76 Correspondence: Wallingford to Sidney Wallingford, 6 September 1915, WFC.

77 AG, 25 September 1915, p. 5.

78 TS, 30 September 1915, p. 4.

79 Correspondence: Wallingford to Braithwaite, 29 June 1936.

80 Correspondence: Wallingford to Harrowell, 1 November 1915, WFD.

81 Correspondence: Wallingford to Mrs Warden, 13 January 1915 [sic 1916], WFD.

82 Correspondence: Wallingford to Braithwaite, 29 June 1936.

83 Correspondence: Wallingford to Mrs Warden, 15 August 1916, WFD; No Better Death, op. cit., Malone to Sandford, 17 May 1915, p. 197, 5 June 1915, p. 231; Correspondence: Wallingford to Braithwaite, 29 June 1936.

84 Correspondence: Wallingford to Son, 6 September 1915, WFC.

85 Ibid.

86 Taranaki Daily News, 8 January 1916, p. 3.

87 ‘List of New Zealanders on Gloucester Castle Hospital Ship No. 20’, no date, WA207/5, ANZ; Military Personnel File: Jesse Wallingford, History Sheet, Proceedings of Medical Board, 13 April 1916 and related papers, AABK W5586, 0136689, ANZ; Wendy Holden, Shellshock (London, Channel 4 Books, 1998), pp. 22–3; The initial casualty report published in New Zealand stated that Wallingford was suffering from syncope, a temporary loss of consciousness caused by low blood pressure: AG, 13 September 1915, p. 7.

88 Correspondence: Godley to Robin, 21 June 1917, Godley papers, AAYS 8649, AD12/21, ANZ; Correspondence: Wallingford to Son, 6 September 1915, WFC; Colonist, Nelson, 27 September 1915, p. 5; Correspondence: Wallingford to Allen, 11 July 1916, op. cit.; Military Personnel File: Jesse Wallingford: Proceedings of a Medical Board, 16 January 1917, Wallingford to Officer Commanding Auckland District, 1 February 1917, Chief of General Staff to Camp Commandant Trentham, 12 March 1917 and related papers, History Sheet, W5586, 0136689, ANZ; Correspondence: Wallingford to Braithwaite, 29 June 1936.

89 Auckland Star, 8 March 1941, p. 11, and 6 June 1944, p. 6.

90 Correspondence: Geoffrey Wallingford to author, 5 June 2015.