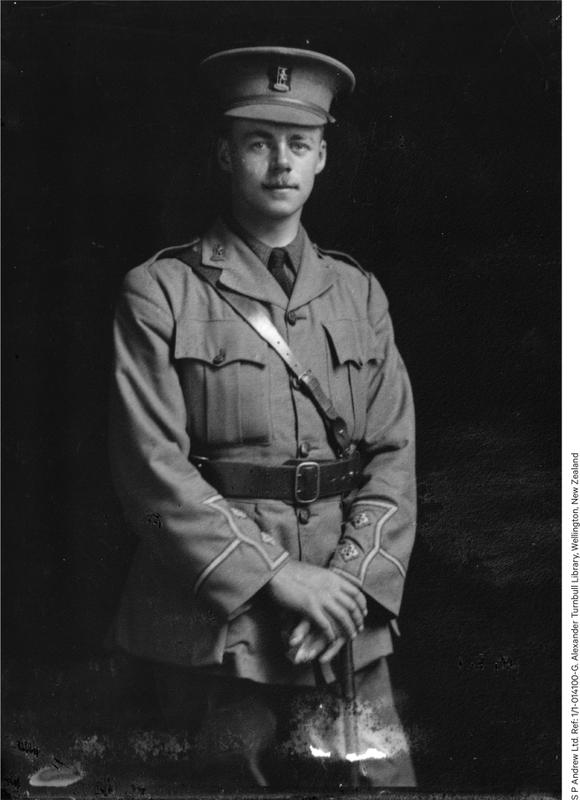

Lindsay Inglis joined the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) in April 1915 as a 20-year-old second lieutenant, and spent the entire war as an officer with the New Zealand machine-gunners, attached on-and-off to the New Zealand Rifle Brigade (NZRB). I came across his papers at the Alexander Turnbull Library while researching the exhibition ‘All Quiet on the Western Front?’, which was held at the Waikato Museum of Art and History in Hamilton. Inglis’s First World War letters and diaries are extensive, and his detailed descriptions of the war are full of insight.1

In his study of a First World War officer, American historian Marco Dracopoli asserts that:

Leadership is in many ways an intangible trait as it encompasses a wide body of other significant traits: courage, empathy, intelligence, competence, and command presence to name just a few. In WWI, officers had to balance their role as disciplinarian, combat leader, and paternalistic father to those under their command. Therefore, while competence and calmness when in combat were important aspects of good leadership, they were by no means the only desired traits. Officers were now encouraged to get to know the men under their command, to come to understand their interests and needs so as to improve morale, ward off combat fatigue, and increase combat efficiency.2

Inglis was born in Mosgiel on 16 May 1894 into a Presbyterian family. His grandfathers were Dr Hugh Inglis and Reverend James Kirkland, both emigrants from Scotland. He was educated at Waitaki Boys’ High School in Oamaru from 1907 until 1913, and went on to study law at the University of Otago until he interrupted his studies to enlist on 30 April 1915. On 9 October 1915, Inglis sailed as a machine gun (MG) officer in the 2nd Battalion NZRB for Egypt and then the western front. In March 1916, he was promoted to captain in A Company 1st Battalion NZRB. He would later command the 3rd New Zealand MG Company. In March 1918, he was promoted to major and transferred to command the Otago Company of the New Zealand Machine Gun (NZMG) Battalion. The Otago Company was attached to the 3rd Battalion NZRB in late September 1918.

Inglis was influenced by a number of people prior to the First World War. The qualities shared by his grandfathers were transmitted to the following generations. Doctor and minister are professions requiring compassion, understanding and respect towards patients and parishioners. These qualities were also passed on to Inglis’s own children and grandchildren — an aid worker just after the Second World War and a school chaplain can be found amongst them.

At Waitaki Boys’ High School, the rector (headmaster) Frank Milner noticed Inglis’s leadership potential. Inglis became house prefect in 1911, captain of the First XV when he was in the sixth form, and the following year, captain of the First XI and head prefect. Inglis’s role model at school was Thomas Holmes Nisbet, the son of a pastor and ‘best all-round athlete, captain of football, boxing champion and head boy’.3 Nisbet is mentioned several times in Inglis’s First World War memoirs and letters. At school, Inglis was assistant librarian in 1909, when Nisbet was the librarian.4 The following year, Inglis became librarian and was assisted by Athol Hudson, a 1914 Rhodes Scholar who would be killed on 14 July 1916 near Armentières.5 Nisbet was killed at Gallipoli on 7 August 1915.6 Inglis was very affected by both deaths, particularly Nisbet’s; he kept the death notice from Dunedin’s Evening Star all his life and it can still be found in the papers held by his family.

Inglis was also influenced by the officers he met through the Cadet Corps. All pupils of Waitaki Boys’ High School were involved in the Navy League, and in 1913 General Godley had complimented them on their ‘efficiency, and [they were] recognised throughout Otago as one of the premier Cadet Corps’.7 Inglis was very attracted by a military career, although the rector encouraged him to study law.8

Inglis, in turn, became a role model for other pupils, including Selwyn Kenrick, who would join the NZRB in 1916 and fight at Le Quesnoy in November 1918.9 Upon learning of Inglis’s death in 1966, Kenrick wrote to his wife, Mary Inglis: ‘I have known Lindsay all my life, and have always had a great admiration for him as a man and as a soldier. He was head prefect at Waitaki Boys’ High School when I first went there in 1912, and I well remember him getting his commission [of second lieutenant, on 1 July 1912] while still at school.’10

While training at Trentham Camp, Inglis witnessed the leadership shown by Lieutenant Colonel Harry T. Fulton, commanding officer of the 1st Battalion of the newly formed NZRB. Fulton, who was nicknamed ‘Old Bully’ by the men, was in the habit, according to Inglis, of ‘blasting officers and N.C.O.s in the presence of their men … The method was apparently deliberate, based on the principle of keeping the officer on his toes so that he dared not let any of his subordinates be slack but passed the influence down the chain of command.’11 Although Inglis found the method unattractive, he noted that Fulton was fair in his decisions. Lieutenant Colonel A. E. Stewart, commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion NZRB, was nicknamed ‘Granny’ because of his age and apparent inexperience. However:

It became clear, as soon as his battalion got into action, that the most cool and fearless man in it was Colonel Stewart. From that time there was no question but that he had the confidence of his battalion, which, indeed, had always liked him. ‘Granny’ stuck to him throughout; but it lost any sting it ever had and became solely a term of endearment.12

As Marco Dracopoli writes:

The ability to improve unit morale was a crucial skill of good leaders as it not only improved the lives of enlisted soldiers, but also improved combat effectiveness of the unit as well. Troops with high morale were willing to fight longer and harder against greater odds than troops that were exhausted physically and mentally. However soldiers’ morale was not the only factor in determining a unit’s combat capability. An officer’s ability to not only lead but also exude an aura of calm in an otherwise chaotic environment was crucial to maximising a unit’s potential.13

Early in his war, Inglis learned this through example. We see this at the Battle of Flers–Courcelette, when he witnessed the action of a fellow officer, Lieutenant Edward Kibblewhite, in charge of a section in 1st NZMG Company:

[Kibblewhite] had noticed two riflemen lying wounded on a part of the road where high explosive shells were plumping in rapid salvoes. ‘Two of your men are lying wounded on the road, Captain. We’d better get them out of it or they’ll be blown to bits’, he shouted in my ear. I hope I managed to look as cool as he was, but I certainly did not feel it. One of the wounded men was hit again as we carried him to the shelter of a hole in the clay bank. Kibblewhite was killed later in the morning. Both he and Captain Frank Turnbull, who commanded the Wellington Company which attacked up the road from our position, were fine leaders whom it was an education and an inspiration to watch in action.14

Throughout the war, Inglis also witnessed the behaviour of other officers, Australian, British and even American, and he acknowledged that New Zealand officers were closer to their men. There could be two reasons for this. After the casualties suffered on the Somme, newly commissioned New Zealand officers came through the ranks. New Zealanders were also less class-oriented. As a result, discipline amongst the Anzac troops was better than in the British Army, as officers were less feared and less removed socially speaking.15 It is therefore not surprising to see Inglis being critical of British officers or the old British system. Inglis showed how New Zealand soldiers reacted when they were told in August 1916 in a lecture given by Major Campbell, who commanded the Bayonet Fighting School at General Headquarters, that German soldiers had to be killed even when they surrendered: ‘We don’t want prisoners. We have to feed prisoners. What we have to do is to kill Huns. Kill plenty of Huns. The only good Hun is a dead Hun.’ Inglis was appalled by such attitudes:

If my own men can be accepted as a fair sample — and I think they were — the average New Zealander did not put Major Campbell’s precepts into practice. Like every other large body of men our numbers included a few who would do outrageous things occasionally; but those among us who could bring themselves to kill a ‘tame Jerry’ were few indeed.16

Inglis wrote: ‘[soldiers’] endurance and fighting spirit must be based on confidence in their own fighting quality and staying power, not on a discipline produced by menace and brutality but as one educed [sic] by esprit de corps and a healthy morale’.17 Inglis’s memoirs are based on the letters he wrote to his fiancée, and reveal how the young officer’s judgment and point of view evolved during the course of the war. It has been argued that ‘The most obvious difference between [good and bad officers] was not in their tactical awareness as one might expect, but in the relationships they had with their soldiers. No matter how tactically aware an Officer may be, it counts for little unless he can command the trust, loyalty and respect of his men and is able to inspire them.’18

And this will be achieved by:

- being sincere and caring

- being a good listener

- giving his time and friendship

- showing genuine interest in his men as individuals

- competing with and against his men

- having a sense of humour

- being scrupulously fair

- leading from the front by example

- being calm, level-headed, with good common sense, and

- never showing indecisiveness.19

An indirect way of satisfying the first four of these criteria was through censoring letters. Inglis was fascinated by how different his men were and by how differently life had treated them, and he tried to avoid being judgmental about ways of life he was not used to. In Egypt in February 1916, he wrote:

I see [my men] of course every day. I hear them talking among themselves, and I get talking with them. Then I censor their letters. Letters are peculiar things … they give one quite a lot of information about the writer[,] more particularly if you know the man apart from his letters. They interest me a lot these chaps; but just what advantages I have so far personally gained out of studying them I really couldn’t say if you asked me, though a chap must surely gain something from it.20

Inglis was younger and less experienced than his men but he showed understanding, tolerance and a capacity for adaptation.21 By getting to know them and responding to them accordingly, Inglis was building an esprit de corps. Inglis wrote extensively about the men in his MG section in the 2nd Battalion NZRB and the roll of his section can be found amongst the papers kept by his family. Written in a very small notebook, it is surprising to see that Inglis sent the roll to his fiancée given the risk of it falling into enemy hands. Several weeks later he sent her a photograph of the section:

This original entry became considerably more detailed in Inglis’s memoirs:

24/257 [sic, 24/357] Corporal Arthur John Billington of Auckland, Law Clerk, 22 years 10 months, became Transport Sergeant to the 3rd N.Z. M.G. Company on its formation. After considerable service as transport sergeant he transferred to one of the sections as Section Sergeant and was commissioned early in 1918. He was O.C. No. (2) Section Otago M.G. Coy. with me at the Armistice. We left Germany together on 25th January 1918 [sic, 1919] and came home to N.Z. together on the S.S ‘Ajana’. He is a solicitor in Auckland and was a fine rugby forward who represented his Province after the war.23

Inglis’s inclusion of a roll of the section at the end of his memoirs shows how much his men meant to him; he even refused promotion in order to stay with them. The initial interest shown by Inglis for his men never wavered; while writing his memoirs, he was still trying to gather as much information as he could on each member of the section.

Nicknamed ‘Skipper’ by his men, Inglis acted as a paternal figure. In Flers on 17 September 1916, he wrote:

That evening, bidding a reluctant farewell to our travelling kitchens and their good, hot food, we trudged some distance towards the forward area in a cold downpour to occupy a ditch full of collapsing burrows, gluey mud, and water. I managed to wheedle the Quartermaster’s only jar of rum from him on the plea that A Company was the only one small enough for one jar to serve, so that a liberal tot all round lightened the wretchedness of the night.24

After two weeks on the front line, Inglis and his men left the Somme in pouring rain at the end of September 1916:

We passed the stage where we dared to halt and spell the men in case we should never be able to get them moving again towards the shelter and hot food that I was determined they should reach. Clinkard, who was now the solitary sergeant left to the company, Robbie and I laboured up and down the column, pulling to their feet those who fell or lay down and pushing them on again. I do not know what we said or did to them; but we kept them moving … We struggled up the greasy slope past Caterpillar Wood to arrive at last, complete to a man, at a muddy archipelago where tarpaulin and ammunition-box shelters formed the islands. The men lay down in the slush. The rain beat down. It had taken us seven and a quarter hours to come six miles.25

Inglis was level-headed and showed common sense, traits that are essential in a good leader. He described several incidents that highlight how his decision-making benefited the whole unit. Inglis did not show any weakness under pressure, and did not hesitate to convey his personal opinion. On 4 June 1917, for example, Inglis was asked to nominate a lance corporal, whose uncle was a general, for a commission. He replied that the lance corporal was not yet ready. The promotion went to another soldier, who ‘had both experience and an outstanding capacity for leadership’.26 A year later the lance corporal was promoted on his own merit after he had gained the required experience.

Inglis made sure that his men trained well, that their equipment was up to scratch, and that he had the best men for the job. When the NZMG Corps was reorganised in February 1918 from five to four companies, Inglis’s 4th Company was disbanded as it was the youngest unit. Inglis then commanded the newly named Otago Company — formerly the 3rd Company — in the also newly named NZMG Battalion. He was not allowed to select the men, but, having talked to his sergeant major and worked out a code between them beforehand, the latter managed to get him the best soldiers.

Inglis frequently resorted to what he called ‘conveying’ or ‘borrowing’. After his Otago Company inherited the former 3rd Company’s battered equipment, there was an overnight transformation:

The 4th Company’s transport vehicles which had been in use only ten months in the field, had been perfectly kept, all had the same brass hub-caps and all had [a] complete set of tools. The 3rd Company’s wagons, on the other hand, had long records of active service. Next morning saw a remarkable rejuvenation of the limbers in Otago park; but there could be no doubt that each lot of limbers was in its correct place, for those in the Otago park bore its green star on a black ground while the others bore the sign of the extinct 4th Company, a black star on a red ground. Our painters were quick nocturnal workers.27

Inglis’s men’s ‘conveying’ — from missing linchpins from limbers in dire need of replacement to horses — resulted in a better-equipped unit and gave them an increased chance of survival in the lines. At the New Zealand transport depot at Grantham in England, Inglis complained about the state of their horses. Thanks to a ‘bradbury’ — a £1 note — and an understanding dragoon sergeant major, when the machine-gunners left Grantham ‘somehow or other our chargers seemed to have developed into a fine set of animals overnight; and, as we were well on our way to France a few hours later, the mystery was neither enquired into nor explained so far as we knew’.28

In Polygon Wood, Inglis came across a young lieutenant posted from New Zealand who had not seen any fighting. This young officer had several times avoided taking his men into battle. In his memoirs Inglis does not identify the soldier, whom he nicknamed ‘Hindenburg’. We do not know whether the soldier suffered from any medical condition, and doctors could find nothing wrong with him, but Inglis stepped in and sent a note to a medical officer: ‘Dear Ted, Please send this bird home. He is not worth his rations.’29 The officer was eventually returned to New Zealand, Inglis thereby removing a soldier who could have destroyed the esprit de corps that he had built.

Inglis frequently showed compassion when instead he could have referred transgressing soldiers to higher authorities. Early in October 1918, while in the vicinity of Fontaine-au-Pire and Beauvois-en-Cambrésis, he came across two young British soldiers who were hiding in a concrete pillbox:

Shaking with fright at the din of the artillery. We hauled them out. They admitted with tears that they had flunked the attack and slipped away from their comrades. After pointing out how disgraceful their conduct was for British soldiers and telling them they might well be shot if their own officers knew what they had done, I showed them the direction their unit had taken and ordered them to catch it up. That pulled them together, and they doubled off at their best speed in the proper direction to make amends.30

If Inglis showed compassion towards subordinates and fellow officers, he was harder on officers, whom he expected to be good leaders. After the Somme, Inglis was shocked by the state of the 3rd NZMG Company he was to take over. Although the guns were kept in very good repair, the men’s uniforms, arms and equipment were in an appalling condition. Inglis explained that this had not been noted because the company was scattered along the line, and that ‘if General Fulton had known the true state of affairs, there would have been fireworks with a vengeance’. ‘Old Fin [Allan C. Finlayson] was a terribly casual C.O. Indeed, the only explanation of his getting through the war without being court-martialled must be that he was such a thoroughly nice chap and so popular with everyone that somebody always did his work or covered up his omissions.’31

Inglis strove for personal excellence and expected the same from others. He discussed at great length in his memoirs the choice of Colonel Blair as his commanding officer. Colonel Duncan Barrie Blair DSO, MC and mentioned in dispatches (three times) was made commanding officer of the NZMG Battalion in March 1918. Born in Wanganui on 29 June 1873 and educated at Wanganui Collegiate, Blair was a New Zealand Staff Corps officer who had fought during the Boer War and who left with the Main Body of the NZEF on 16 October 1914. He was at Gallipoli with the Canterbury Mounted Rifles and at all the major battles New Zealanders fought on the western front.32 On Blair’s appointment in March 1918 Inglis recalled that the latter ‘had no technical knowledge of machine guns, and [that] he never grasped the principles of their tactical employment. To these defects he added a capacity for sneering and injustice that not only deprived him of the respect of his subordinates but soon earned for him the dislike and even the hate of all ranks.’33

Inglis deplored his commanding officer’s indecisiveness, poor decision-making, and lack of judgement and fairness. In late April 1918, near Bus-lès-Artois, two machine-gunners from Inglis’s Otago Company were charged with theft after taking turnips from a field. From April 1918, opportunities for looting increased as New Zealand troops advanced into areas where crops had been left in the fields as civilians fled from the fighting.34 The soldiers ‘were convicted by the Colonel, who sentenced them both to 28 days’ Field Punishment No. 2 — a sentence which was probably doubled by the fact that I gave them good characters’.35 This sentence entailed the soldiers being handcuffed and losing their pay for 28 days, although they remained with their unit. Blair’s decision could have been a gesture to preempt further stealing amongst the troops, but Inglis easily demonstrated that he had made a poor decision. The turnips were valued at one franc — less than a shilling. Inglis continued: ‘Under the Common Law no one can be convicted of stealing anything growing out of the ground of under the value of one shilling. A franc is only eightpence halfpenny.’36 Inglis argued the point with Blair, and the latter had to give in and the conviction was quashed.

Inglis and Blair had a strained relationship, which lasted until Blair’s departure for New Zealand in early December 1918. Blair’s apparent indecisiveness could have simply stemmed from burn-out; a professional soldier who had fought throughout, he could have suffered from mental exhaustion, as other officers and men did. It is again difficult to pinpoint a reason, or even to know whether he was portrayed accurately by Inglis, given that we do not have a corroborating source. However, Inglis mentions too many details in his memoirs to dismiss the accusations entirely. He wrote that other officers had problems with Blair and openly criticised the commanding officer in front of the men.

In November 1918, shortly after the Armistice, Major J. B. Parks, the NZMG’s second-in-command, went to a commanding officers’ school in England and Inglis became acting second-in-command. During this time, Inglis had to step in to quell incipient mutiny among the men of the NZMG Battalion when, on 29 November, the Otago Company, now commanded by Major Cimino, refused to parade. Inglis went to see Colonel Blair:

I asked him what he was going to do about it.

‘Nothing’, he said. ‘If Cimino can’t control his company, I’ll take him before the G.O.C. to explain himself.’

‘But you must do something’, I urged. ‘You ought to have done something long ago. It’s right through your battalion now, and you know it’s all aimed at you.’

‘If Parks comes back to France; you’ll go back to that Company, so you can do it yourself if you like’, he sneered.

‘Very well. If you won’t, I’ll have to’, I said.37

The men paraded, and Inglis took the names of about 20 of them for some ‘more or less imaginary irregularities in dress’. When asked by Inglis for the reason for their mutiny, they replied that it was because of breakfast. Pushed further by Inglis, they admitted that they wanted to get rid of Colonel Blair:

I do not remember exactly what I said because it came out pretty well at white heat; but I recollect pointing out that the task we had set ourselves would not be completed until we had stood over the enemy to enforce the terms we had imposed. I cursed them for blotting the name of their Corps and no doubt let them see how sore I felt that this behaviour had occurred in a unit that I had myself commanded so long and so recently.38

The soldiers whose names Inglis had jotted down all received 28 days’ field punishment. A corporal whom Inglis does not name was arrested, but was never court-martialled. It has been impossible to find other sources giving Blair’s point of view. The official history of the machine-gunners in France does not shed any light on this or any other indiscipline described by Inglis in his memoirs. Nor do the diaries of Brigadier General Hart, although Inglis recalls several conversations he had with him.39 Christopher Pugsley does not mention indiscipline amongst the New Zealand machine-gunners after the Armistice in his book On the Fringe of Hell, which is dedicated to this topic amongst New Zealand troops.

Disquiet amongst the ranks occurred again on 30 November, when the Canterbury and Auckland companies refused to march from Cattenières to Solesmes. Blair left Inglis to deal with this indiscipline, and Inglis persuaded them to march. Meanwhile he was handed ‘“a List of Grievances against Lt. Col. Blair”, carefully paragraphed, signed by four privates who subscribed themselves “Representatives of the Wellington M.G. Coy.” and requested that the O.C. Company should forward the document direct to the G.O.C.’.40 Inglis obtained similar lists from both the Auckland and Canterbury companies. He decided to deal with the indiscipline himself, given that talking to Blair appeared fruitless. While the Otago Company was on a muster parade, he received their list of grievances:

‘That is most peculiar, for it is signed so and so (reading the names of the four subscribers) “Representatives of the Otago M.G. Coy.” — damned queer representatives for a fighting unit — they haven’t smelt much powder’, I announced and, turning to the man who had brought it out, ‘How did you work this, C? Had a small committee to compose it and hadn’t had time to circulate it, I suppose?’

‘Yes, sir’. C replied.

‘Then you’ve got yourself into a nice jam. What you have done is conspiring to mutiny, and, as you are still on active service the punishment is death. However, we’ll deal with that side of it later. In the meantime, as most of you seem to know nothing about this piece of paper, I’ll read it to you’, and I read it, making at the end of each paragraph my previously thought-out comments.

When I had finished, C stood up and asked, ‘Could I say something, Sir?’

‘What do you want to say?’

He said he now realized how foolish he and the very few others who had had anything to do with the matter had been. He could, he assured me, speak for them as well as himself. They would drop the whole thing and would never again be connected with any insubordination.

‘Very well, if that’s the way you really feel about it, we’ll treat it as if it had never happened’, I said and, tearing up the paper, threw it into the bonfire beside me.41

The mutiny was led by men who had never fought and who had been assigned to the NZMG Battalion after the Armistice. They would not have known an esprit de corps and camaraderie built on shared experiences by comrades-in-arms. Inglis noted that these men were ‘agitators’ who had organised strikes from the time they left New Zealand to their arrival in the NZMG Battalion.

Another contribution to the mutiny was that some of the officers of the NZMG Battalion were openly critical of their commanding officer. The ranks must have known this, which led to further dissatisfaction and came to a head after the Armistice when the men had more free time. Officers were also responsible for the relaxation of discipline amongst the men. Inglis’s talks to both officers and men galvanised them, and no further show of mutiny occurred in the NZMG Battalion.

Inglis showed a propensity for self-derision and an eye for comedy. His memoirs and letters are full of jokes and anecdotes that recount potentially tragic scenes in a self-deprecatory way. Inglis recalls, for example, how Captain L. S. Cimino described what happened to him and Inglis while they were on a reconnaissance near Hébuterne in July 1918:

‘The Skipper’, he recounted, went poking about to find these forward posts, and I went with him. It wasn’t voluntary on my part, but, of course, one must obey one’s senior officer. We found the posts all right, and we survived that; but on the way home Jerry began to hate us with five-nines. The first one landed about twenty yards away. Of course field officers take no notice of a thing like that, so I couldn’t either. The next one was closer. He had a look at that. The third was darn close; and that was about the one occasion when I thanked heaven his legs were longer than mine. There was a dug out not far away. I think he did it in two seconds — I know I broke three — and we were a dead heat at the door. ‘No, no, Cim’, he said, waving me aside, ‘Senior officers first!’ And I know he did get in first because I fell on him.42

In September 1915, while at Trentham Camp, Inglis’s batman told him that some of the men had hidden a barrel of beer in a tent:

As I approached the tent, someone said, ‘Look out!’ in an agitated stage whisper, which was followed by some hurried scuffling. I gave them time to tidy up before I appeared in the doorway of the tent and started to chat … Walking farther in I took my stand over the spot where I thought the barrel was buried under the sandy floor … Strained looks all around the tent.

‘Hello’, I said, ‘There’s a piece of wood or something here.’

‘Nothing there, sir’, a chorus assured me.

‘Oh yes there is’, I insisted, scraping some of the sand from the barrel top and banging my heel down on it. ‘It’s hollow.’

‘We haven’t noticed it before’, someone said.

‘Come on’, I said, ‘Where’s the pump. I want a beer.’

‘Will you have a beer sir?’ a relieved voice asked; and when I replied in the affirmative, mugs of beer were withdrawn from underneath every kit round the tent. They pumped a large one full for me.

After I had had a couple, I said, ‘This is no good, you know. We don’t want the whole M.G. Section on the mat for planting beer in camp in defiance of the Defence Act; but there’s no prohibition outside the camp boundary. Fifty yards away over the fence there’s a perfectly good sand-hill. I think you’d better plant the next one in that.’43

Inglis’s ability to laugh at himself in front of his men made him even more respected. On 14 July 1917, during a horse show at Erquinghem, west of Armentières, Inglis entered his horse, Captain, ‘for the heavy officers’ charger class’. Inglis had not ridden the horse since before Messines, and his knee injury made the horse difficult to control.

We walked round the ring and trotted round very nicely. Then the judge said, ‘A hard gallop, please, gentlemen.’ With a bound Captain was into full stride and past the next two horses. He was definitely out for manners, so I pulled him out of the ring … We careered full split towards the river to the great diversion of the troops. A fence on the left and wagons and a marquee on the right made it impossible to change direction. Captain seemed to have a notion of jumping the fifty-yard wide river. Not until he reached the cinder tow-path did he realize that the canal was too wide to jump. Searing up the track with his hooves, he came to a stop within a foot of the bank.

This would have been bad enough, but there was to be more. My light felt hat, which had blown off just before we pulled up, was handed up to me by a digger; and, as Captain was standing quietly, I stuck an arm through the reins and proceeded to refit my puggaree on the hat. Captain, catching sight of the other horses as they continued to canter round the ring a couple of hundred yards away, suddenly set sail in their direction without a warning snort. Again we were in full career before all eyes; and, although I kept him well away from the ring, we had gone a quarter of a mile before I could stop him.

One of the subalterns maliciously informed me that evening that, as Eastwood, the Brigade-Major, watched us belt, he said, ‘Yes — both mad!’44

Inglis’s concerns about the war are candidly recorded in his letters to his fiancée, May Todd. In May 1918, he wrote how war had changed him so much that he did not know what he would be like when he returned to New Zealand:

Things that once would have left their mark on my thoughts for weeks pass absolutely unnoticed — or at any rate with just a passing glance bestowed, then off into the limbo of forgotten things … Perhaps we have tried too often when the experience of pain and sudden death and suffering was new to find a reason for it all and failed, that we’ve now ceased wondering altogether, viewing it as the natural and usual source of things from force of habit.45

Inglis had recently been in contact with British and American officers who had been posted to his unit as observers. These soldiers were new to the war, and Inglis realised how blasé he had become when he compared his lack of emotional response to theirs.

The leadership abilities originally spotted on the cricket and rugby fields of Waitaki Boys’ High School were developed further as war transformed Inglis into a military leader in the trenches of the western front. He showed courage under fire, a genuine interest in his men, compassion and fairness, as well as a decisiveness that gained his men’s respect. Moreover, Inglis did not hesitate to voice a dissenting view when he thought he was right, which strained his relationship with some officers. The war made him more understanding of others as well as a good judge of character, traits which served him well and prepared him for a prominent legal career in civilian life and for his role as a brigade commander during the Second World War.

Notes

1 I would like to thank Lindsay Merritt Inglis’s granddaughters and their late mother for giving me access to their family papers.

2 Marco Dracopoli, ‘A New Officer for a New Army: The Leadership of Major Hugh J.C. Peirs in the Great War’, Gettysburg Historical Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, 2014, pp. 50–8.

3 K. C. McDonald, History of Waitaki Boys’ High School 1883–1933 (Auckland, Whitcombe and Tombs, 1934), p. 233.

4 Waitakian, vol. 3 (1909), p. 195, Inglis family papers.

5 Memoirs: Lindsay Inglis, Inglis Papers, MSY-5455, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington (hereafter ATL).

6 Lieutenant Thomas Holmes Nisbet (8/767) fought in the Otago Infantry Battalion. See Auckland War Memorial Museum’s Cenotaph records.

7 Waitakian, vol. 1 (1913), p. 33, Inglis family papers.

8 Correspondence: Lindsay Inglis to May Todd, 12 April 1912, Inglis family papers.

9 For information on Selwyn Kenrick (14539), see Auckland War Memorial Museum’s Cenotaph records. Kenrick was medical-superintendent-in-chief of the Auckland Hospital Board from 1946 until 1961.

10 Correspondence: Selwyn Kenrick to May Inglis, 18 March 1966, Inglis family papers.

11 Memoirs: Lindsay Inglis, Inglis Papers, MSY-5455, ATL.

12 Ibid.

13 Dracopoli, op. cit., pp. 50–8.

14 For information on Edward Henry Turner Kibblewhite (10/960), see Auckland War Memorial Museum’s Cenotaph records; Memoirs: Lindsay Inglis, Inglis Papers, MSY-5455, ATL.

15 J. G. Fuller, Troop Morale and Popular Culture in the British and Dominion Armies 1914–1918 (Oxford, The Clarendon Press, 2006).

16 Memoirs: Lindsay Inglis, Inglis Papers, MSY-5455, ATL.

17 Ibid.

18 Doug Proctor, quoted in Sydney Jary, ‘Reflections on the Relationship Between the Led and the Leader’, Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, vol. 146, no. 1, 2000, pp. 54–6.

19 Ibid.

20 Correspondence: Lindsay Inglis to May Todd, 12 February 1916, Inglis Papers, MS-0421-02, ATL.

21 Ibid., 15 December 1915, Inglis Papers, MS-0421-01, ATL.

22 Notebook: Lindsay Inglis, 28 November 1915, Inglis family papers.

23 Memoirs: Lindsay Inglis, Inglis Papers, MSY-5456, ATL.

24 Ibid., Inglis Papers, MSY-5455, ATL.

25 Ibid.; ‘Robbie’ refers to Edmund Colin Nigel Robinson (9/439). He was gassed at Messines and suffered from chronic pulmonary disease. See Military Personnel File W5922, 64/0098906, Archives New Zealand, Wellington (hereafter ANZ).

26 Memoirs: Lindsay Inglis, Inglis Papers, MSY-5456, ATL.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 Major Allan Cross Finlayson (9/439) was first in the Otago Mounted Rifles before being posted to 3rd Machine Gun Company and then the Canterbury Company of the NZMG Battalion. See Military Personnel File W5922, 24/0039984, ANZ; Memoirs: Lindsay Inglis, Inglis Papers, MSY-5456, ATL.

32 Auckland War Memorial Museum Cenotaph record; See also J. H. Luxford, With the Machine Gunners in France and Palestine (Auckland, Whitcombe and Tombs, 1923).

33 Memoirs: Lindsay Inglis, Inglis Papers, MSY-5456, ATL.

34 Christopher Pugsley, On the Fringe of Hell: New Zealanders and Military Discipline in the First World War (Auckland, Hodder & Stoughton, 1991), pp. 273–5.

35 Memoirs: Lindsay Inglis, Inglis Papers, MSY-5456, ATL.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 John Crawford (ed.), The Devil’s Own War: The First World War Diary of Brigadier-General Herbert Hart (Auckland, Exisle, 2008).

40 Memoirs: Lindsay Inglis, Inglis Papers, MSY-5456, ATL.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Correspondence: Lindsay Inglis to May Todd, 26 May 1918, Inglis Papers, MS-0421-07, ATL.