William Blomfield, or ‘Blo’ as he signed his work, never went over the top or gripped the levers of power beyond the not-so-commanding heights of the mayoralty of Takapuna.1 As historian Mark Bryant once quipped, ‘Nobody ever got a Victoria Cross for drawing cartoons in wartime.’2 Nevertheless, as one of the foremost cartoonists of the age, Blomfield occupied a position that offers a revealing perspective of New Zealand at war.3

Samuel Blomfield and Emma Watts Collis, Blomfield’s parents, arrived in Auckland on the Gertrude in 1863.4 According to family history, on their departure from London the male settlers were given an axe, a spade and a Bible as tools to develop and civilise a ‘savage country’; a rifle and bayonet, issued upon arrival under militia regulations, added to these means.5 A joiner by trade, Samuel found work in construction until the 1867 opening of the Thames goldfields, whereupon he tried his hand as a digger. Failing to make any significant discoveries, he returned to Auckland and his previous trade in 1880.

William Blomfield was born on 1 April 1866, the fourth of eventually 12 children. His recollections of his childhood note an early fascination with the limited illustrated material he could access on the Thames goldfields, as well as his habit of scribbling ‘efforts in artistry everywhere’.6 This included chalking sketches of big-bearded miners on the back of the chimney; ‘crude caricatures of the parson’ scratched with a pin ‘on the unvarnished woodwork of the pew’; and the use of a school slate as a canvas.7 One reflection reminisces about ‘playing the wag’ from his usual school so that he could attend Parawai School, where he would be allowed to draw. As Blomfield recalls: ‘The Parawai scholars were mostly Maoris and the Maori is, or was, really clever with his pencil, horses being his pet subject. My time was taken up in the drawing of jockeys on their horses.’ The episode concludes on the postscript that, after those two days, Blomfield’s teacher also performed ‘some artistic work, drawing a supplejack over my back’.8

The determination to draw persisted.9 Blomfield left school at 14 and eventually became a clerk in Henry Wade’s architectural firm in Queen Street, Auckland. Here he obtained new targets for caricature, noting that ‘much of my time there was spent caricaturing my boss, extremely stout and bearded’.10 In 1884, drawing became a career in itself, when Blomfield was taken on by the New Zealand Herald, where he helped with lithographic work, and his artistic talents were put to use providing character sketches, political reports and panoramic scenes. He was, for example, sent on a field assignment to sketch the 1886 Tarawera eruption.11

With photography inheriting the role of direct witness, newspaper cartooning would increasingly focus on caricatures and commentary. It was hardly surprising, therefore, that when his contract with the Herald expired Blomfield joined the New Zealand Observer, a publication with a solid focus on this use of cartooning.12 Although the Observer claimed circulation across New Zealand and in Australia, it was primarily an Auckland-based and -focused society paper.13 In the Observer’s own words, the paper’s strength ‘was in its social gossip’ and devotion ‘to other people’s affairs’.14 Blomfield remarked that the Observer was ‘not in favour with certain circles especially the highly respectable and high society’, and had an editorial policy of attacking ‘political and municipal misdemeanours without fear’.15

Despite its muck-raking tendencies, the paper paid at least lip service to the idea that it was a respectable institution. According to the masthead, the publication was ‘smart, but not vulgar; fearless, but not offensive; independent, but not neutral; unsectarian, but not irreligious’. Describing this respectable populist line, Robin Hyde, who worked at the Observer in the 1930s, noted ‘we are trying, more or less, to steal Truth’s thunder without their unpleasantness: that is, to write bold and free as other papers mayn’t, but certainly not to haunt divorce courts and put harassed housemaids in the headlines’.16

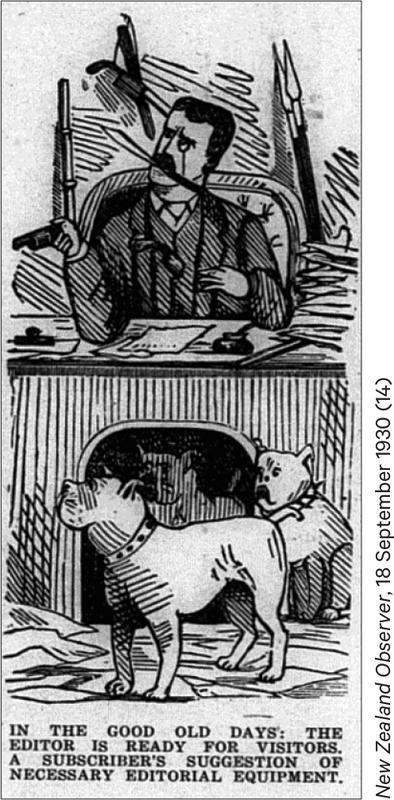

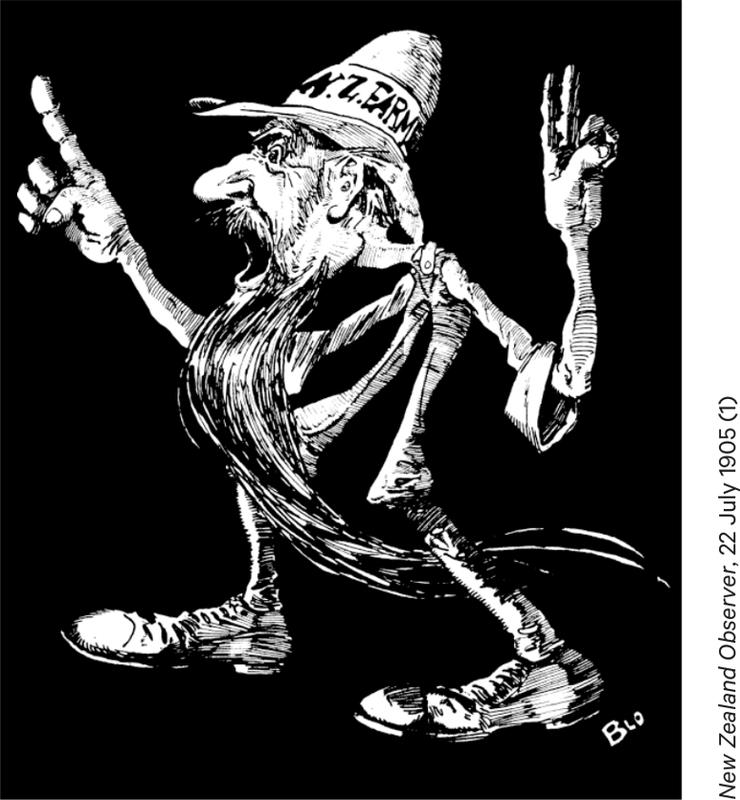

Figure 1. ‘In the good old days: the editor is ready for visitors.

A subscriber’s suggestion of necessary editorial equipment.’

_________

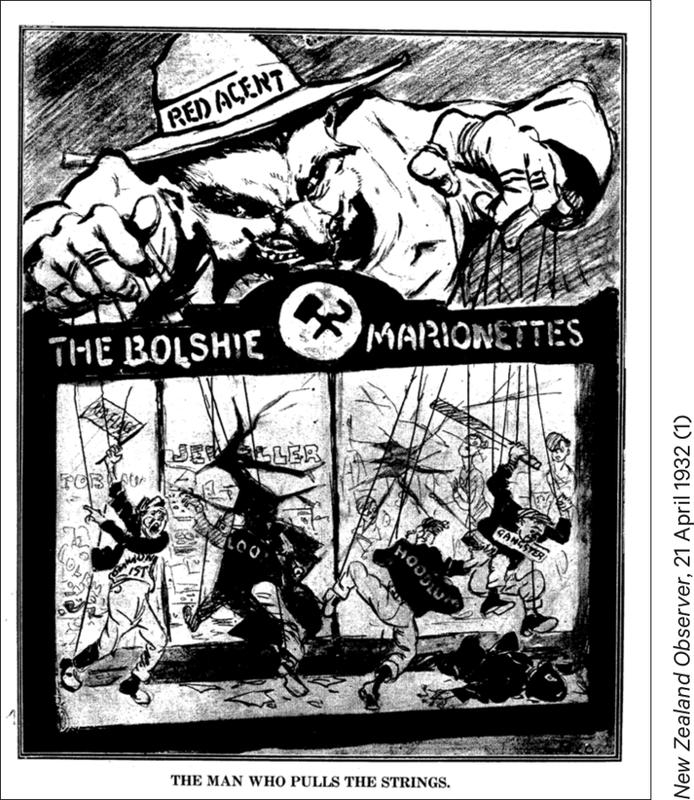

Figure 2.

_________

In pursuing this line, genteel airs were not always maintained, and one subscriber submitted a sketch of an editor preparing to meet his critics armed to the teeth (Figure 1). This hyperbole was a response to actual episodes in which editors came into physical confrontation with those who felt their reputations had been slighted. In one case, an irate individual arrived at the Shortland Street office with a riding whip in hand to extract his vengeance.17 Another incident saw editor and critic locked in ‘an almost death-struggle’, each endeavouring to throw the other down the stairs.18

Alongside physical altercations, the editorial line also provoked legal battles. In April 1899, for example, the mayor of Kumara, Thomas Byrne, had attended an evening’s entertainment reported to have been ‘of a bacchanalian character’, which left him rather intoxicated.19 Making his way home with two friends in the early hours of the morning, the trio encountered two cleaning women heading to work.20 At this point accounts diverge and slip into euphemistic language. The women were variously ‘threatened’, ‘interfered with’, ‘assaulted’ or ‘jostled’.21 Whatever the specifics, the women screamed, the police got involved, and Byrne concluded that the publicity would damage his reputation.

A man of some social and political influence, Byrne is said to have threatened the police with reprisals and issued writs against several papers that reported the incident, demanding £300 (around $53,000 in 2014 dollars) in damages and an apology.22 The Observer refused to offer either, even after other papers had conceded and after a visit from Prime Minister Richard Seddon, a family friend of Byrne’s. According to Blomfield’s account, Seddon begged him to settle the matter while also threatening that the Observer would lose the impending legal action.23 Ultimately, Seddon was correct: Byrne won the case and was awarded £50 in damages. Blomfield’s account darkly records that after the verdict was heard the jury was ‘entertained to a lavish supper in a leading Wellington Hotel’ and that the foreman was appointed to a government position.24

This was not quite the end of the matter. Following the verdict the Observer’s editor W. J. Geddis’s ‘Irish blood was up’.25 Geddis, backed by a sympathetic Wellington police force, succeeded in convincing the cleaning women to bring an action against Byrne. They are reported to have secured £150 in damages.26

Blomfield’s ‘pungent pencillings’ proved a natural fit with the Observer’s racy style of commentary. The doyen of New Zealand cartooning, Ian F. Grant, has described Blomfield’s technique as embracing a modern and lively form:

His style was sometimes dismissed disparagingly as ‘rush and ready’, but along with his younger brother John Blomfield and E.F. Hiscocks, he was one of the first to shrug off the prim, static, relentlessly cross-hatched style of the early New Zealand cartoonists … He was often careless and haphazard about details and background, but his work had a vitality and visual flow that links him directly to today’s leading cartoonists.27

Such work matched the Observer’s courting of reaction. If Blomfield’s earlier office caricatures had ‘raised a rumpus’, and if sketches made during court cases had prompted threats of violence, then his work at the Observer would take provocation to new heights.28 Prominent share broker James Lennox, whom Blomfield often mocked for his height, foot size and politics, so resented a cartoon that he threatened to shoot Blomfield if he ever produced another. Blomfield did, and lived to speak of it.29 The German consul, Carl Seegner, was so incensed by a caricature that he challenged Blomfield to a duel and threatened to run the artist through. Fortunately, a friend talked Seegner down.30

The most famous instance of his testing the boundaries came when Blomfield lampooned Judge Edwards’s supposed partiality towards an attractive female witness in a caricature entitled ‘Justice is Not Blind’.31 Unamused, Edwards claimed that the cartoon exposed a judge to public contempt and he initiated court proceedings.32 Ultimately, Attorney General v William Blomfield proceeded to the Supreme Court, where it was dismissed.33 A brass band and an escort of solicitors are said to have accompanied Blomfield on a victory march, although there is some question over whether this was a tribute to Blomfield and artistic freedom or indicative of Judge Edwards’s unpopularity within the legal profession.34

Blomfield’s work also embraced the populist quality of the weekly and its claim to be the authentic voice of the common man.35 This tended to be achieved by two major means. The first was to cast the ordinary citizen — whether in shirt-sleeves or a suit, a man or a woman — as wholesome and upright. Although dashes of caricature and critique make the result less sentimentalised than a Norman Rockwell rendition, Blomfield’s ‘man on the street’ is generally depicted as right-minded and possessing a homespun common decency.

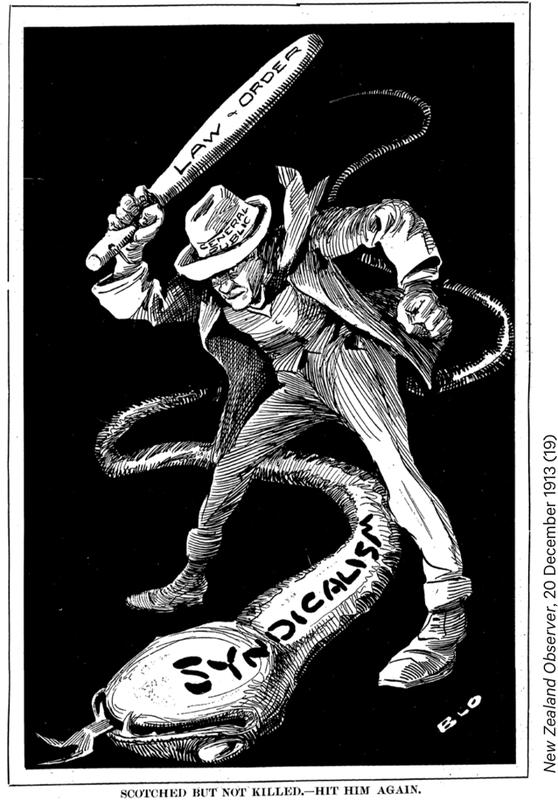

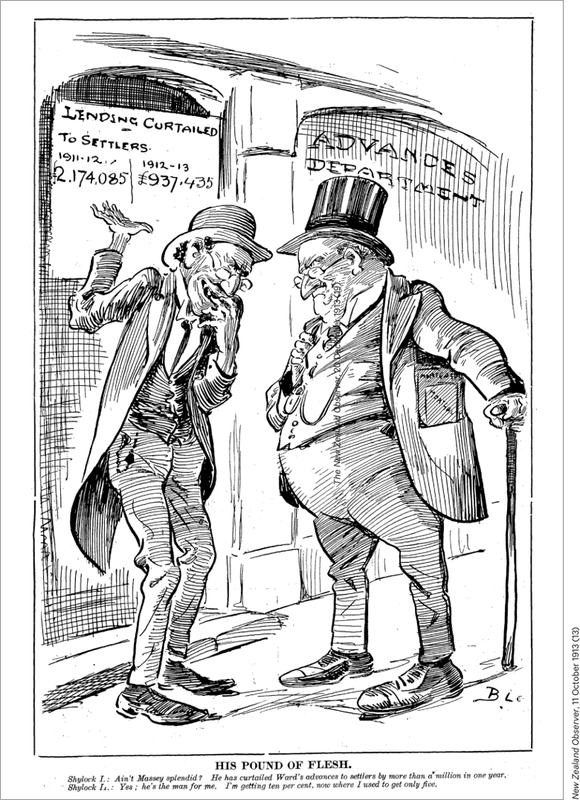

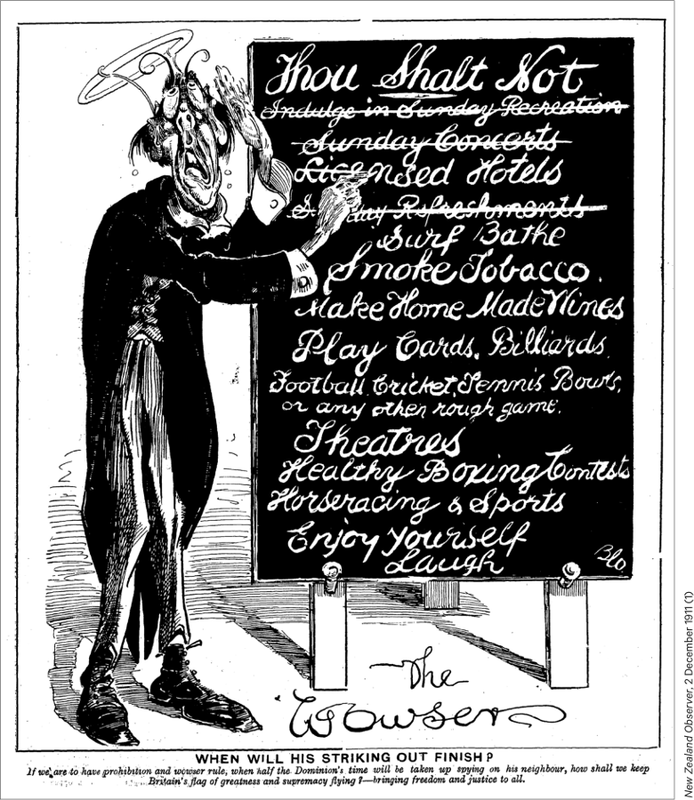

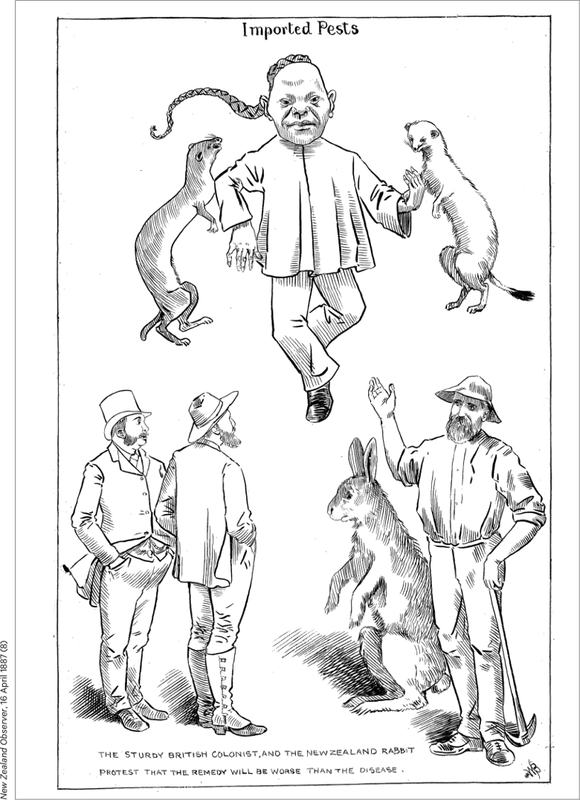

Blomfield sometimes drew himself within his scenes — recognisable by his bowler, whiskers and pipe — his expression showing that he shared the readers’ exasperation or amusement at the state of things. The Observer’s second major means of displaying solidarity was through showing the common man as beset on all sides by various enemies of the people, who threatened social harmony and the man-in-the-street’s prospects. Indeed the Observer’s pugilistic populism was wielded against a rogue’s gallery of foes. Blomfield attacked farmers, strikers, capitalists, ‘wowsers’, the ‘yellow peril’ and the red menace (Figures 2–7), and such venom sits rather curiously alongside his obituary’s claim that his ‘creed was a warm and tolerant liberalism’.36

At the outbreak of the First World War, Blomfield was 48, had become involved in local politics (he would serve as the mayor of Takapuna from 1914 to 1921), was a husband and a father of five, and had become a co-owner of the Observer as well as its chief illustrator. In this last role he demonstrated immense industry, producing a full-page, tabloid-size cover cartoon and numerous smaller illustrations for the 24 pages of each weekly issue.

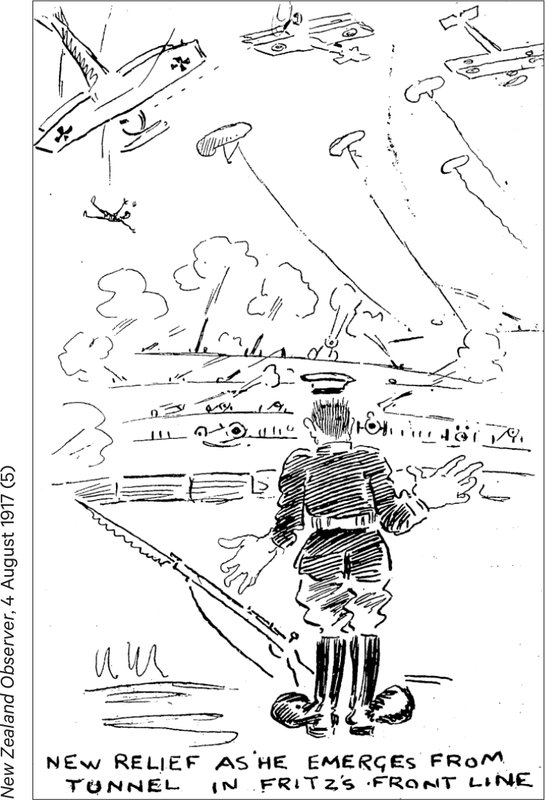

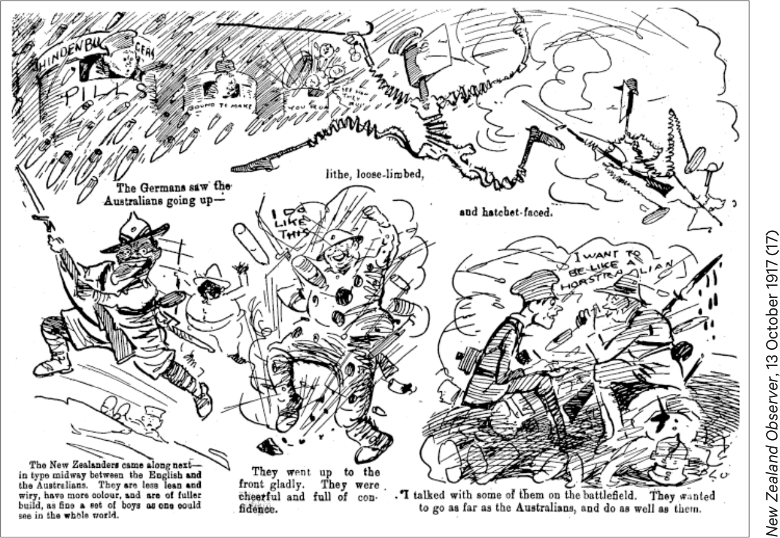

Throughout 1914–18 much of this public space was dedicated to war-related material, expressed with more of Blomfield’s populist approach. Rather than square-jawed supermen, Blomfield’s sketches of Tommy Fernleaf typically presented the New Zealand soldier as an ordinary man in uniform, fired by a worthy cause and lionised with a dose of affectionate irreverence. Indeed, Blomfield’s treatment of war correspondents’ reports and cable news typically possessed a subversive undertone. He captioned his illustrations of Ashmead-Bartlett’s famous Gallipoli dispatches ‘Giants All: Britain’s correspondent, Ashmead Bartlett spins a few little fairy tales on Australasian soldiers at Gallipoli.’37 Correspondent Philip Gibbs’s Passchendaele report received a similar treatment. His remark that ‘They [New Zealanders] went up to the front gladly. They were cheerful and full of confidence’ was sardonically illustrated by a grinning Fernleaf riddled with shells and proclaiming ‘I do like this’ (Figure 9).

Populism drove the Observer’s castigation of those it deemed enemies of the public good; in the paper’s mind this was anyone who undermined the war effort and undervalued the ordinary citizen-soldier. When businessman and president of the Auckland Acclimatisation Society C. A. Whitney commented that providing hospitalised soldiers with a barber was pampering, and that ‘far too much has been done for returned soldiers’, Blomfield made a cartoon of a soldier, missing both his arms, shaving himself with his feet (Figure 8). The caption asked whether this arrangement would satisfy Whitney. The editorial then took this derision to greater heights:

As far as this paper is aware, the same remark might apply to Mr Whitney himself — a good deal has been done for him. But no one remembers Mr Whitney returning, from any war with any bullets in him. No one recollects Mr Whitney as being a private soldier at Lone Pine amid the ghastly havoc of artillery, rifle and bomb fire. No one remembers Mr Whitney coming down the ridge to the dressing station minus a hand, minus a leg, minus an arm, filled full of shrapnel splinters, blind, choking with blood, choking with thirst. No one remembers Mr Whitney doing this cheerfully for 5s a day — and shutting up about it.38

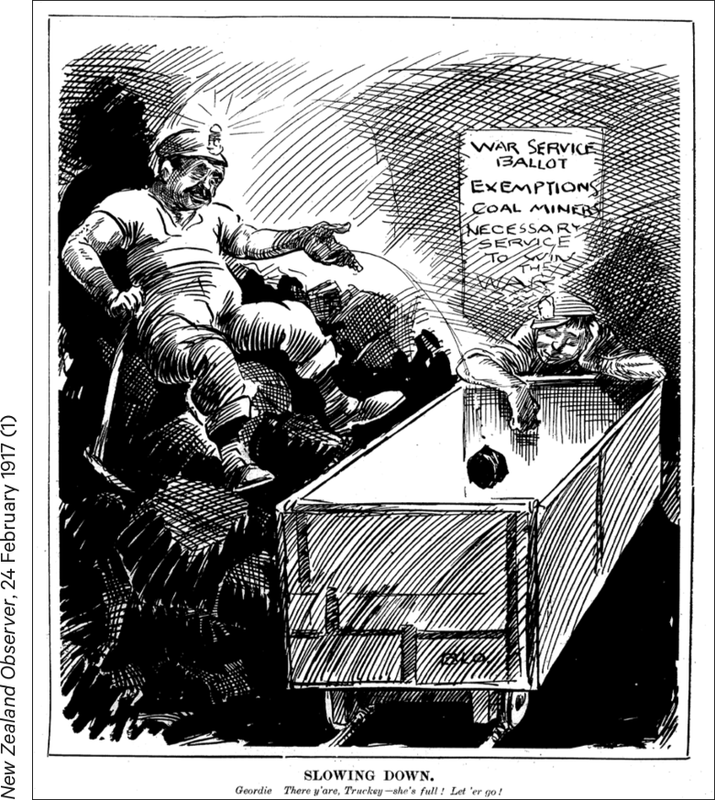

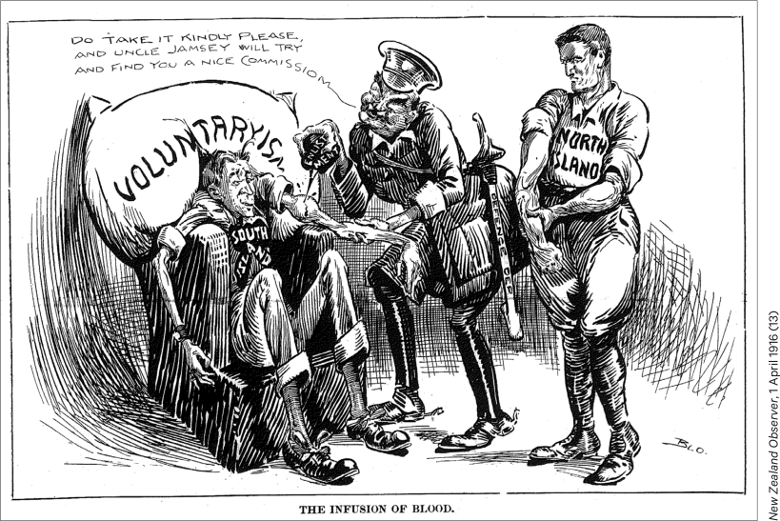

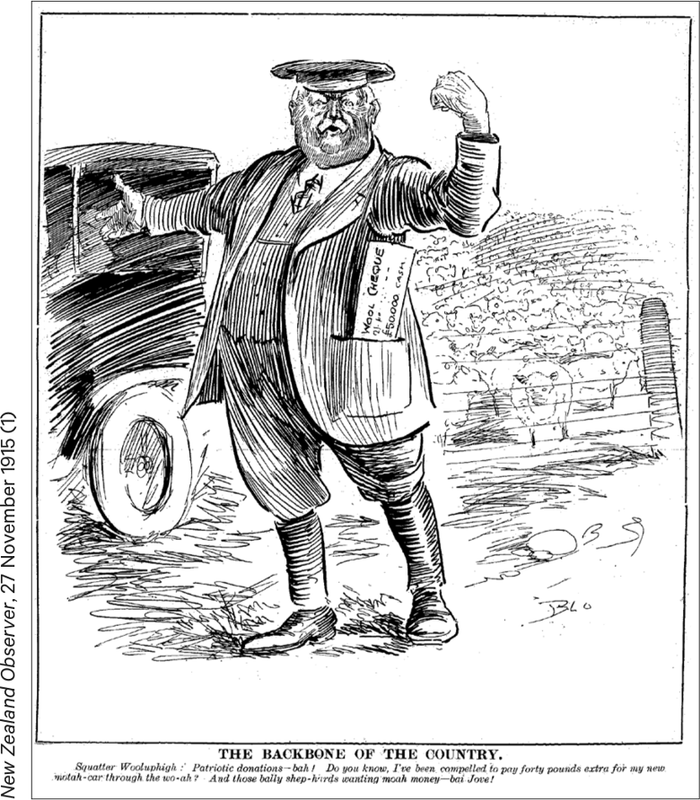

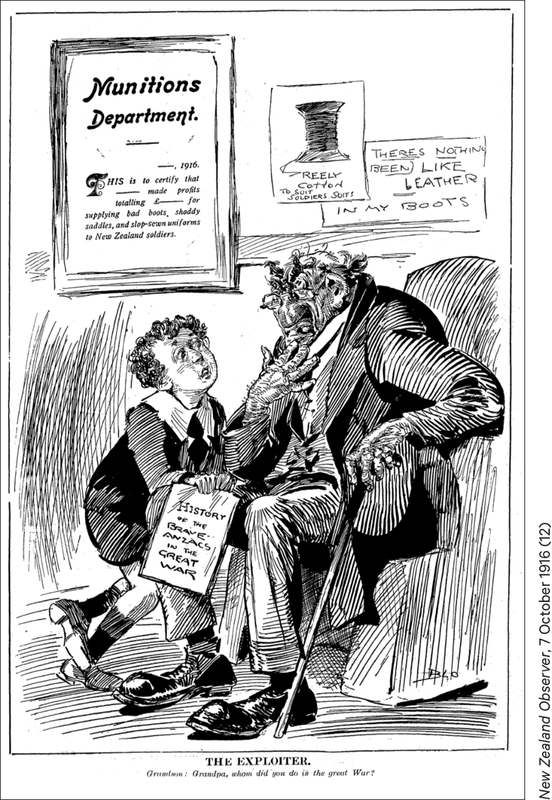

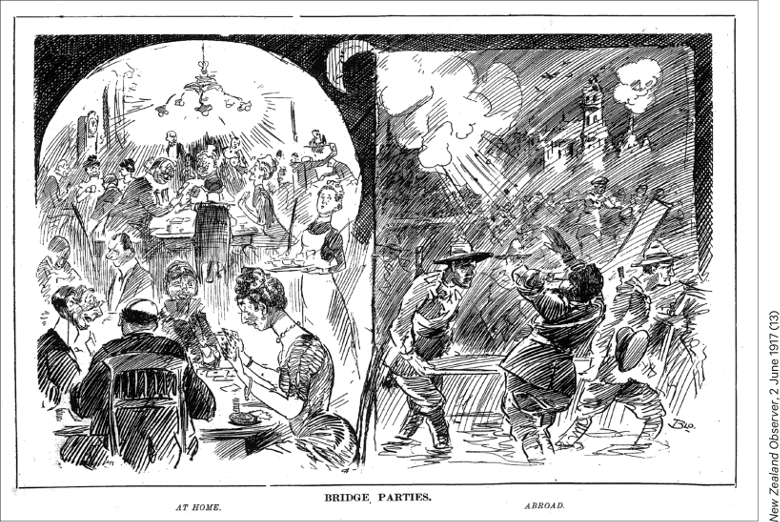

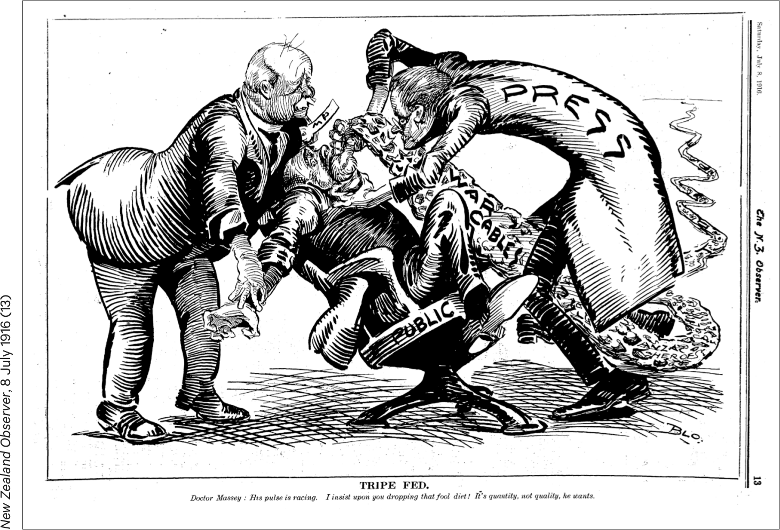

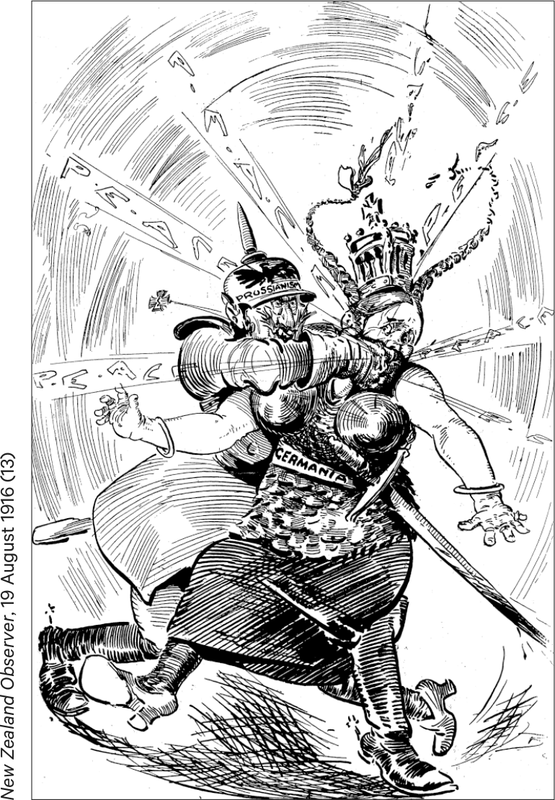

Blomfield’s targets were many: he went after farmers for being war profiteers, the labour movement for being shirkers or disloyal, business and industry for being exploiters, general frivolity for being an affront to frontline sacrifice, the South Island for failing to meet its recruitment quotas, Australia for failing to introduce conscription, and the press for cramming war-cable tripe down the public’s throat (Figures 10–16). External enemies received similar treatment: Blomfield typically focused on the Kaiser and/or Prussian militarism as the root cause of the war, sometimes making deliberate distinctions between these elements and the German people (Figure 17).39

Mark Bryant once asked whether the wartime cartoonist’s position was that of a ‘crusader’, a ‘white rabbit’ or an ‘organ grinder’s monkey’: that is, an iron-souled pugilist thundering opinions whatever the consequences; an apolitical drone whose job was a soft option to military service; or a steady worker churning out a contribution shaped by editorial lines. Bryant concluded that ‘most cartoonists were a combination of all three’.40 However, while all of those three elements can be detected in Blomfield’s position, the role of ‘crusader’ would seem to be dominant. His co-ownership of the paper gave him increased editorial freedom and free range to his natural disposition. Indeed, Blomfield continued to freely ‘voice’ his sensibilities through 1914–18, and the war may have intensified his convictions.

One study of New Zealand wartime cartoons, including Blomfield’s, would seem to support the view that the Observer used cartoons to press its point of view and notes that such cartoons ‘can be regarded as propaganda’ under the rationale that ‘They disseminated the views of a particular segment of society, seemingly to achieve conformity.’41 Given that much of Blomfield’s work can be seen as aiming to sway mass opinion via evocative appeals, this is not entirely wide of the mark. However, describing ‘propaganda’ as something systematic and quite separate from a ‘normal’ dissemination of ideas doesn’t entirely explain Blomfield’s position in a wartime society.42

Figure 7. ‘The man who pulls the strings.’

_________

Figure 8.

_________

Figure 9. ‘The Germans saw the Australians going up—lithe, loose-limbed, and hatchet-faced. The New Zealanders came along next—in type midway between the English and the Australians. They are less lean and wiry, have more colour, and are of fuller build, as fine a set of boys as one could see in the whole world. They went up to the front gladly. They were cheerful and full of confidence. I talked with some of them on the battlefield. They wanted to go as far as the Australians, and do as well as them.’

_________

Figure 10. ‘THE BACKBONE OF THE COUNTRY. Squatter Wooluphigh: Patriotic donations—bah! Do you know, I’ve been compelled to pay forty pounds extra for my new motah-car through the wo-ah? And those bally shep-hards wanting moah money—bai Jove!’

_________

Figure 12. ‘THE EXPLOITER. GRANDSON: Grandpa, whom did you do in the great War?’

_________

Ultimately, the war saw a continuation of the fourth estate’s position between the government and the public. The Observer cast itself as both an ardent supporter of the cause and a critical friend of government policy. One part of this equation must be that, peace or war, the business concerns of running a newspaper remained the same. Ian Grant puts it well:

In war, as in peace, newspapers saw their primary role as providing their readers with news of importance and interest as soon as possible; high-minded though this was, it was inextricably coupled with the commercial imperative of maintaining the circulations which brought in the advertising essential to profitability. Restrictions on delivering the news was anathema to the press.43

Indeed Blomfield could be less than respectful of censorship, and the Defence Department filled a file on the Observer’s breaches of regulations in printing rumours and sensitive information.44

The Observer remained enticed by rumour, gossip and the promise of populist outrage, and its willingness to critique policy and lampoon public figures could ruffle officialdom. It explored the politics of sacrifice and was amongst the most vocal proponents of introducing conscription, ridiculing the authorities, notably the Minister of Defence James Allen, as coddling shirkers and for creating inequality by delaying its introduction.45 Commenting on outbreaks of disease at Trentham Camp, the paper asked, ‘if the people of New Zealand could be asked what is the gravest political necessity of the moment they would be justified in saying “Allen must go”’.46 Blomfield happily wielded the image of the suffering soldier to underscore his critiques and commentary. When Allen commented that he thought New Zealand soldiers were smoking more than was good for them, Blomfield created a cartoon in which his likeness scolded a soldier missing a leg (Figure 19). Allen, one suspects, must have felt that Blomfield was a force unto himself.

The Observer at war largely kept doing what it had already been doing in peace. According to Blomfield’s obituary, ‘In the life of Auckland Blo held a unique place. There was probably no man as well known, and no man more popular.’47 The laundering quality of obituaries aside, the observation captures how Blomfield’s work, and livelihood, rested on being in tune with readers and potential readers, and on playing to his audience’s attitudes and prejudices. As historian Jay Winter has noted, First World War propaganda only became effective propaganda when it possessed a ‘synergistic relationship with opinion formed below’.48 Arguably it is from sensationalist and biting commentary such as Blomfield’s that researchers can best gain a sense of prevalent wartime attitudes, including the sense of the conflict as a necessary and righteous struggle to oppose a German conquest of Europe, a moral obligation felt towards the soldier’s ordeals, and a passionate outrage towards ‘shirkers’, ‘profiteers’ or ‘traitors’, however those categories were comprehended.

Figure 14. ‘Bridge parties.’

_________

Figure 16. ‘TRIPE FED. Doctor Massey: His pulse is racing. I insist upon you dropping that fool diet! It’s quantity, not quality, he wants.’

_________

Figure 17.

_________

Blomfield had a very personal connection with the front. Eric, his eldest son, had volunteered within the first fortnight of the war. Serving with the field artillery, he was described as ‘one of the first ashore at Gallipoli’, and ‘one of the last sections to leave’.49 Transferred to France, he served until his discharge on 15 October 1918 — a total of 4 years and 45 days of service, during which he was wounded several times.50 ‘Young Blo’ seems to have shared many of his father’s views and habits. His personnel file lists his pre-war occupation as ‘journalist’ and, like his father, he put his talents to use during the war, serving as editor of a troop magazine, the Gunner, and sending home a stream of correspondence and frontline sketches (see figure 18), some of which the Observer reprinted.51

This information stream may well have influenced Blomfield’s eye-rolling at melodramatic renditions of the front.52 Eric also complained about the ‘tall tales’ of New Zealand soldiers, and his correspondence mixed his ‘characteristic cheerfulness and boyish vivacity’ with frank discussions of the seriousness of the war.53 A postscript to an Observer article outlining Eric’s latest news, which noted several casualties and his being shot in the thigh, concludes: ‘We are winning the war, hooray, but you can understand what a hell it is, a continual screaming, roaring, crashing noise, dust, smoke, gas and fire, wrecked waggons [sic], dead horse [sic] and dead men.’54 Like his father, these descriptions stood alongside a conviction about the war’s ultimate purpose:

I’ll bet no soldier of this generation on either side will ever want another war. It seems all wrong that millions of people should have to suffer through the doings of one madman. I am convinced that good will come out of it and that the world will be a better place to live in when it is all over.55

William Blomfield’s wartime output never won him a VC — although he did receive the King’s Silver Jubilee Medal — and his work never achieved the heights that fellow New Zealand cartoonists Gordon Minhinnick and David Low attained with their Second World War cartoons.56 However, there is some evidence of sustained public interest. The Whanganui Art Gallery collected some of his wartime output, and selections were republished in interwar anthologies, such as Cassell’s Great Cartoons of the War and the French War Cartoons of All Nations.57 Contemporary New Zealand publications on the war have displayed an interest and have reproduced some of his output.58

After the war, the Observer flourished until the late 1920s, when circulation and advertising revenue declined sharply during the Depression.59 However, the weekly survived until 1954. Blomfield continued to produce cartoons up until his death on 2 March 1938, aged 72. Reportedly some of his last words were ‘What about the cartoon?’60 The Observer would overcome that problem, for a week at least, by printing William Blomfield’s image in his front-page spot as a tribute to a life devoted to drawing.

Figure 19. ‘Major Swinger: Since I have knocked off cigarettes and taken to toffee I feel that I’ve won the war. Mr W Owser: Ah, of course, WE the successful appellants can be trusted—but the soldier, No! We must pluck the filthy cigarette from his mouth, dear brothers! Fernleaf: Packet of green, please. Tobacconist: Can’t sell ’em to you—you’ve got heart trouble! The Colonel: Huh! What the devil have YOU been doing to yourself? Smoking cigarettes, I suppose? Fernleaf: What! you’ve been giving the Fritzes fags? Ain’t it against the regulations to kill prisoners in cold blood? Stop That Coffin! Undertaker: Have a cigarette, soldier—and I’ll see you later.’

_________

Notes

1 All references to ‘Blomfield’ refer to William and not his younger brother John, who also produced cartoons, typically signed ‘J. C. Blomfield’.

2 Mark Bryant, ‘Crusader, White Rabbit or Organ-Grinder’s Monkey?: Leslie Illingworth and the British Political Cartoon in World War II’, Journal of European Studies, vol. 31, no. 123, 2001, p. 345.

3 For an analysis of the possibilities cartooning can offer historical study, see Thomas Milton Kemnitz, ‘The Cartoon as a Historical Source’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 4, no. 1, 1973, pp. 81–93.

4 Unpublished Research: ‘Blomfield Family Tree’, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

5 Unpublished Autobiography: William Blomfield, Private Collection of Ian F. Grant, p. 1.

6 Ibid., p. 4.

7 Ibid., pp. 2–4.

8 New Zealand Observer, Auckland (hereafter NZO), 18 September 1930, p. 17.

9 As Blomfield would later note, ‘The youth of to-day had a tremendous advantage over the youth of my boyhood days who had any artistic inclinations or instinct.’ Unpublished Autobiography: William Blomfield, p. 2.

10 NZO, 18 September 1930, p. 17.

11 Unpublished Autobiography: William Blomfield, pp. 23–9; NZO, 18 September 1930, p. 17.

12 The paper was launched under the title of the New Zealand Observer and Free Lance, but was renamed as the New Zealand Observer when the Wellington spin-off, the Free Lance, was launched in 1900. The name was later shortened to the Observer.

13 NZO, 23 September 1905, p. 6.

14 Ibid., 18 September 1930, p. 13.

15 Unpublished Autobiography: William Blomfield, pp. 48, 50.

16 Robin Hyde, Passport to Hell (Auckland, Auckland University Press, 1986; originally published 1936), p. vii.

17 NZO, 18 September 1930, p. 14.

18 Ibid.

19 Otago Daily Times, 13 June 1900, p. 5.

20 NZO, 21 April 1900, p. 2; NZO, 16 June 1900, p. 5.

21 See, for example, West Coast Times, 26 August 1899, p. 4; Hawke’s Bay Herald, 26 August 1899, p. 3.

22 NZO, 18 September 1930, p. 13. The current-day figure is calculated using the Reserve Bank’s Inflation Calculator, http://www.rbnz.govt.nz.

23 Unpublished Autobiography: William Blomfield, p. 56.

24 Unpublished Autobiography: William Blomfield, p. 57.

25 Ibid., pp. 56–7.

26 Free Lance, Wellington, 8 September 1900, p. 6.

27 Ian F. Grant, ‘Blomfield, William’, from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 5 June 2013, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/biographies/4b41/blomfield-william.

28 NZO, 18 September 1930, p. 17.

29 For an example of Blomfield’s depiction of Lennox, see ibid., 29 August 1891, p. 11.

30 Ibid., 18 September 1930, p. 21. For the offending cartoon, see 31 August 1907, p. 19.

31 Ibid., 6 September 1913, p. 19. A second cartoon, ‘Experience’, on page 17 of the same issue was also cited.

32 This episode came three years after another major case that pitted cartoon commentary against establishment sensibilities. In December 1910, Ercildoune Frederick (Fred) Hiscocks produced a satire of William Massey and the Reform Party, which Massey deemed libellous. The case reached the Supreme Court, which found for Hiscocks. For the offending cartoon, see New Zealand Times, 3 December 1910, p. 1. For the verdict, see Wairarapa Daily Times, 16 February 1911, p. 5.

33 For an analysis of the proceedings, see Evening Post, Wellington (hereafter EP), 29 October 1913, p. 7.

34 Grant, ‘Blomfield, William’, op. cit.

35 James Belich has discussed something similar in his concept of early twentieth-century New Zealand’s ‘populist compact’. See James Belich, Paradise Reforged: A History of the New Zealanders from the 1880s to the Year 2000 (Auckland, Penguin, 2001), pp. 22–3.

36 NZO, 10 March 1938, p. 6.

37 Ibid., 14 August 1915, p. 12.

38 Ibid., 19 August 1916, p. 2.

39 In this, Blomfield’s approach might be distinguished from New Zealand representations of the enemy, which, drawing upon pre-war anti-alien and racialist philosophies, presented the war as one against the wider German population. See Steven Loveridge, ‘A German is Always a German? Representations of Enemies, Germans and Race in New Zealand circa 1890–1918’, New Zealand Journal of History, vol. 48, no. 1, 2014, pp. 51–77.

40 Bryant, op. cit., p. 364.

41 Sarah Murray, A Cartoon War: The Cartoons of the New Zealand Freelance and New Zealand Observer as Historical Sources, August 1914–November 1918 (Wellington, New Zealand Cartoon Archive, 2012), p. 98.

42 For further analysis, see Steven Loveridge, Calls to Arms: New Zealand Society and Commitment to the Great War (Wellington, Victoria University Press, 2014).

43 Ian F. Grant, ‘The News in New Zealand Newspapers During World War One’, Turnbull Library Record, vol. 46, 2014, pp. 24–39.

44 For example, see NZO, 15 April 1916, p. 1; AD1 705 9/19/93, Archives New Zealand, Wellington (hereafter ANZ).

45 Paul Baker, King and Country Call: New Zealanders, Conscription and the Great War (Auckland, Auckland University Press, 1988), pp. 42–63.

46 NZO, 14 August 1915, p. 3.

47 Ibid., 10 March 1938, p. 6.

48 Jay Winter, ‘Propaganda and the Mobilization of Consent’, in Hew Strachan (ed.), The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War (New York, Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 216–26.

49 Press, Christchurch, 21 October 1916, p. 12.

50 Military Personnel File: Eric Adam Blomfield, W5520, 93/0015724, ANZ.

51 NZO, 21 November 1914, p. 4.

52 Ibid., 27 November 1915, p. 4.

53 Ibid., 21 October 1916, p. 16.

54 Ibid., 9 December 1916, p. 5.

55 Ibid., 29 September 1917, p. 4.

56 EP, 6 May 1935, p. 4.

57 NZO, 18 September 1930, p. 16.

58 See, for example, Ian F. Grant, The Unauthorized Version: A Cartoon History of New Zealand (Auckland, David Bateman, 1987); David Grant, Field Punishment No. 1 (Wellington, Steele Roberts, 2008); Baker, op. cit.; Murray, op. cit.; Loveridge, Calls to Arms.

59 Grant, ‘Blomfield, William’, op. cit.

60 NZO, 10 March 1938, p. 6.