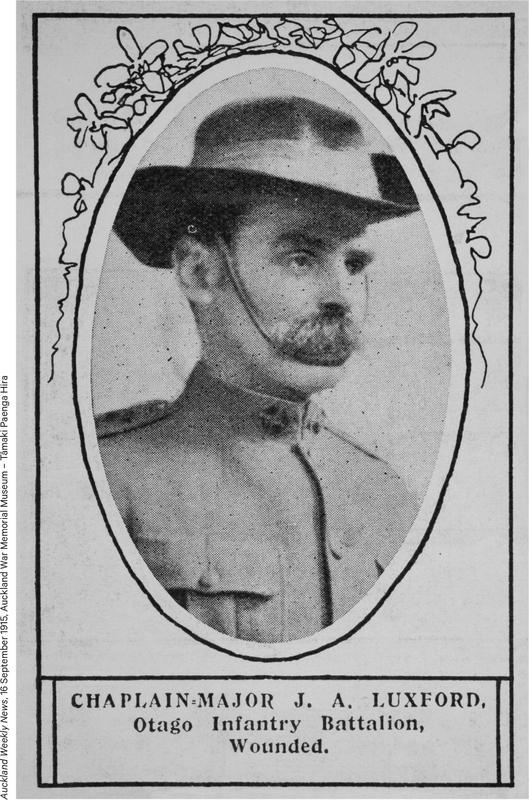

During the night of 11 January 1915, at Zeitoun Camp, Cairo, John Aldred Luxford, the 60-year-old senior chaplain of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF), wrote in his diary: ‘Dreamt I was at home again but had met with an accident.’1 He had been in Egypt for just over six weeks. Six months later, the reality of this portentous dream eventuated.

At the outbreak of war, the New Zealand Methodist Times voiced a sentiment that other churches would have expressed about their own chaplains:

No one is better qualified to represent the Methodist Church in the responsible duties of chaplainship than Mr. Luxford. Among the thousands of young men who are responding to the Empire’s call for service, there are many who are going forth from Methodist homes, and it will be a comfort to those who are left behind to know that ministers of their own Church will accompany the expedition.2

The confidence derived from having this mandate never faded from the chaplains’ thoughts.

Luxford had written to the Methodist Times to farewell his friends and thank them for their messages. He also wanted:

To assure those who have written and those who have not that their lads shall have my prayers and attention. God helping me, I will do my duty … Where we are going, I don’t know, and when we return nobody knows. The 121st Psalm is my daily portion. I am fortunate in being appointed to the flag-ship Maunganui. I know the Church will appreciate the honour. I never felt better physically in my life, and have the testimony of my conscience that the step is in accordance with my Master’s will.3

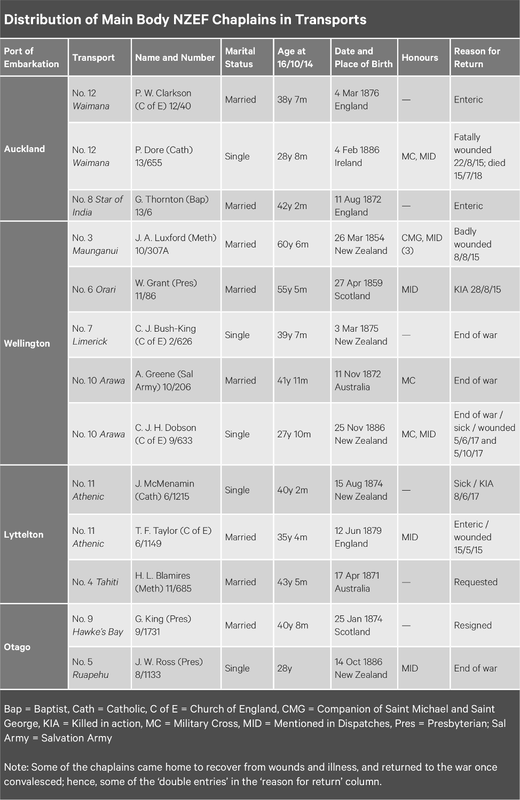

Ten ships departed Wellington on 16 October 1914, carrying over 8000 men and 3000 horses of the Main Body. On board were 13 chaplains, including Luxford, going to war as non-combatants.4 At the second way port of Albany, Western Australia, where the New Zealanders met up with the Australian contingent, Luxford reflected: ‘38 transports and 5 warships. There are about 35,000 troops. What a number of men! Probably 30% of them will never return to their homes. I must do my duty in helping my little company to lead a good life.’5 He was correct. Many of the men, including chaplains, would never see New Zealand again, and those who did return would be changed forever.

As senior chaplain, Luxford was in charge of the 12 others, who are described in the table on page 275. The chaplains’ role was very dangerous, notwithstanding their non-combatant status. Of the 13 Main Body chaplains, 4 received wounds ranging from fatal to severe, and 2 were killed in action. They all suffered illnesses, including enteric issues, sciatica, influenza, dysentery and skin infections. Seven received honours, including the Companion of Saint Michael and Saint George, the Military Cross and Mentioned in Dispatches.

Luxford’s selection as senior chaplain reflected his military experience. He enlisted on 15 August 1914, having served as a chaplain to the Armed Constabulary at Parihaka in 1881, and to the 10th Contingent in South Africa during 1902.6 He was an active member of the Methodist Church’s committee on military and naval affairs, and was well known to civic and political leaders. He had been the president of the 1903 Methodist Conference — a sign of how well he was respected by his own Church. He strongly supported the ‘Territorials’ regime of Major General Alexander Godley, and had publicly defended military camps and troop behaviour.7 He would have eclipsed any potential rivals for the role of senior chaplain in experience, interest and fitness.

Luxford had also shown that he was a man of independent thought. In November 1911, he had clashed with Godley and James Allen, the minister of defence, over Order 172, which sought to ‘regularise [chaplains’] positions [by establishing the notion of chaplains as a “status” as opposed to a military “rank”] and put them on a par with all Chaplains throughout the Imperial Service’.8 This required all of the chaplains then holding commissions to return them immediately. Luxford, who had a commission issued for the South African War, felt ‘annoyed and humiliated’ and thought the order tantamount ‘to a dismissal from the Forces’.9 After a great deal of correspondence, meetings and newspaper attention, Godley partly rescinded the requirement for chaplains with parchment commissions dated prior to the passing of the Defence Act on 24 December 1909 to return them to headquarters for amendment.10 This would not be the last time Luxford disagreed with Godley on a policy matter, but it was the only time his disagreement was so vigorously voiced.

Between 16 October 1914 and 12 August 1915, Luxford wrote 13 diaries, totalling 408 pages. We are very fortunate to have these, as they were rescued from a skip during the renovation of a former solicitor’s office. In these diaries — of all shapes and sizes, written in a mixture of ink and pencil, on board ship, in camp, and at the front, under all sorts of physical conditions, in darkness and in light, heat and cold, at peace and under fire — we meet his family.11 Frank (13/380), his youngest son, served with the Auckland Mounted Rifles and was in the Main Body on board HMNZT No. 8 (Star of India), and his daughter Gladys was a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse at the Walton-on-Thames hospital from 1917 to 1919, during her father’s time there as senior chaplain. John, his eldest son, was an officer on the transporter SS Moeraki.

The diaries provide valuable details and insights into Luxford’s war. We read about his resolute faith in God and his Church, his doubts, ambitions, triumphs, difficulties and fears. His world was seen through his lens, and his reflections were private, containing very critical views on people, places and situations. His writing reflected the diary format in using abbreviations and colloquialisms, and was very personal in its observations.12 The reader will find biblical references, neologisms and figures of speech.13 Luxford was conscious that he was experiencing a significant world event, and he was determined to record it and his part in it. His writing style was descriptive and packed with details about the weather, individuals, situations encountered during the day, and invocations to God to guide and assist his endeavours. Entries almost always ended on a valediction and declaration of love for his wife and his family.

While some may find Luxford’s views on race xenophobic, he was a man of his times. Luxford had strong views on social issues, disapproving strongly of swearing, wet canteens and prostitution. For example, he thought that the 1915 Easter riot in the Haret Al Wassir red-light district of Cairo’s Ezbekieh Quarter was simply the result of drink. He was unequivocal in his love of all things British, and of the incomparable value of Christianity for all things noble and good. He wrote honestly about his own shortcomings, such as his inability to master French and his lack of a ‘better education’, and he constantly exhorted himself to ‘be a friend to the men and exert a good influence’.14

As the war continued, Luxford became conscious of the need to protect information and, while he submitted his letters to censorship, he was more circumspect regarding his diaries.15 These contained very private and critical views, and were only self-censored in a few places, and so he posted them home to his wife for safekeeping, along with various items of interest such as shrapnel and shells purchased on Gallipoli and gifts purchased in Egypt.16

Luxford believed that ‘God is on our side’ and that inner peace and confidence could only be gained through believing in and trusting Jesus Christ. He preached that where Christ did not reign, people were no better than beasts. He was clear that ‘you are your brother’s keeper’ and that ‘knowledge is proud that it knows so much; wisdom is humble that it knows no more’.17 Luxford preached that it was never too late for redemption. His aim was to ‘get among the men and show them how a Christian should be’, and his diaries are dotted with references to his love of God and ‘to Christ’s name be the glory’. Luxford regularly wrote: ‘I commend myself to God. He can keep and inspire’, and that his ‘thoughts and prayers go toward home and loved ones. May God keep them.’18

The Bible was a tool he used to transmit his faith. Sermons were structured to resonate with the men, and he used biblical military references, such as healing the centurion’s servant, to demonstrate the power of faith. He often used his ‘favourites’ in sermons: Psalm 23 — ‘The Lord is my shepherd’ (confidence in the future through the power of God) and Psalm 121 — ‘I lift up my eyes to the mountains’ (the soldier’s psalm). Biblical references were also chosen to capture the views he picked up from the troops to offer them some deeper meaning.

Luxford rated himself above the other chaplains as an orator. However, while some military authorities praised him for a particular sermon, there is little evidence to support his own high assessment of his talents. Some men found his sermonising inspiring; others thought he simply recycled the same message. Soldiers, however, agreed that he did not push religion down their throats, which they appreciated. That he provided comfort at times of death is unquestionable — and death was something with which all military chaplains had to deal.

The chaplains experienced death in various forms even before Gallipoli. Of the 14 deaths during the voyage from New Zealand and in Egypt, four would have stood out for Luxford.19 Lance Corporal Jack Gilchrist (8/323), on HMNZT No. 5 (Ruapehu), died from a self-prescribed morphine dose taken to relieve food poisoning.20 Private Harold Lewis (3/103A), on HMNZT No. 3 (Maunganui), died of pneumonia on 20 November 1914. Luxford, on the Maunganui, wrote that Lewis’s death ‘cast a gloom over the ship and bugles are not sounded tonight’.21 He had purchased some postcards for Lewis at Colombo, and wrote: ‘Oh God help me to speak to these sick men remembering the danger of sickness on board ship and their eternal welfare. Jesus is their saviour but I must be more earnest and try to realise my great responsibility.’22

Lieutenant E. J. Webb (10/1021), whose parents Luxford knew, broke his neck in a diving accident during a crossing-the-equator ceremony on HMNZT No. 10 (Arawa). Dr Captain J. A. Bell (3/156A), a friend of Luxford’s, died on 29 December 1914 in the Abbassia hospital, Cairo, of a brain haemorrhage while undergoing a nose operation. The pomp and ceremony surrounding these deaths, with funeral parades populated by senior officers, bands, firing parties, buglers playing the ‘Last Post’ and chaplains suitably garbed, would contrast dramatically with death on Gallipoli, where there was little ceremony and certainly no pomp.

One can imagine Luxford’s excitement at arriving in Egypt, a ‘country where our Lord spent part of his infancy’.23 Cairo — a city of over a million people, where the contrast between rich and poor was tangible and upsetting, where multiple languages were spoken, and where currency, geography and climate were the complete antithesis of Luxford’s life in New Zealand — was a cultural shock. It took him some time to find his way around such a large city, and he picked up from the locals that only a large military presence was preventing a revolt against British rule. At times he felt unsafe away from the military camp, even sitting high on his horse, Laddie.

Luxford faced various issues in Egypt as senior chaplain. On the Maunganui he had found that some young subalterns objected to prayers, that church parades were disorganised and poorly attended, and that prayers were not receiving enough attention.24 However, he gained the support of officers to remedy the situation.25 He had been insulated from the views of other chaplains on board the Maunganui, but at Zeitoun he had to deal with them and he felt that they blamed him for decisions made by the military authorities over which he had no control.

In Cairo, Luxford was embroiled in arguments with the Church of England chaplains Charles Dobson, Thomas Taylor and Charles Bush-King, who advocated denominational church parades. It took the intervention of Godley to settle the matter. Godley reprimanded the Church of England chaplains ‘for agreeing in NZ to minister to regiments and now [wishing] for denominational services thereby going back on the terms of [your] appointment or commission’. Luxford’s view was that: ‘I am a Church of England member but I don’t mind whether a Methodist or Presbyterian conducts the service. I can worship with all. I can’t understand this narrowness. I wish with General Birdwood and others to attend the Church parades and do not feel inclined to have denominational parades all over the camp.’26 He conceded that Roman Catholics were treated differently because ‘there was a well-recognised cleavage between Protestants and Roman Catholics but I am not in favour of recognising a cleavage between Protestants’.27 Unfortunately, Godley did not formalise this order for non-denominational parades.

At the same meeting, Godley thought that he had settled Luxford’s status as senior chaplain, instructing the others that Luxford was his representative and must be obeyed. All orders were to be obeyed because they were soldiers as well as chaplains. Luxford was to draw up a roster for visiting hospitals and detention barracks, and for performing Sunday services, and no chaplain was to get a substitute without consulting Luxford. Unfortunately, although Luxford relished Godley’s support, his status was not easily resolved and passive resistance occurred through some chaplains not attending meetings.

Disputes also arose over plans to provide men with social entertainment at the homes of Cairo residents and for chaplains to position themselves outside brothels to try to persuade soldiers not to enter. Luxford disagreed with both proposals. He thought that entertaining men in homes was too elaborate and would be seen as patronising, and that the men would resent the chaplains’ presence outside brothels. He argued that the authorities should instead provide suitable entertainment, such as pictures, boxing and concerts, to keep the men in camp. However, Luxford doubtless felt somewhat fragile in his senior chaplain role and let the chaplains make their own arrangements. He was probably mindful of Godley’s direction not to be too undemocratic or too authoritarian. Ironically, at the same time Godley requested Luxford to ensure that chaplains did not attend church parades with walking sticks, that all badges worn by chaplains were listed, and that no church services exceeded 30 minutes.

Godley knew Luxford’s value. He was a safe, obedient pair of hands who could be used to communicate with New Zealanders about the war effort. Godley shared confidential information with him, and Luxford steadfastly preserved its confidentiality.28 Theirs was a symbiotic relationship, and Luxford recognised that ‘the General’s recognition is my source of strength’.29 Luxford was discreet and measured in his treatment of the chaplains and, although he totally disagreed with Godley’s establishment of wet canteens (‘the enemy within the gates’), he remained silent.30 The long voyage to Egypt provided ample opportunity for Luxford to impress both Godley and his wife, and to cement their mutual respect and trust. This relationship endured throughout the war.

Luxford confronted other issues in Cairo. In December 1914, the YMCA wanted tents placed all over Zeitoun Camp and requested that the chaplains supply all the necessary funds. Chaplain Percy Clarkson took particular exception, arguing that the chaplains would do all the work and the YMCA would get all the kudos. Luxford had anticipated this issue, because ‘the plain fact is no provision is made for chaplains’ work. They are expected to have evening meetings, do social work etc and have neither funds to draw from nor authority to enforce or even request help.’31 Luxford again decided to leave this issue to others, and the relationship between the YMCA and the churches turned out to be very positive. The YMCA would provide venues for meetings and concerts, and the men used their facilities for various reasons, not least because they would be free from clergy.

In December 1914, Luxford encountered ‘the coolest piece of impudence [he] ever knew’ when Colonel Chaplain Green, Australian Imperial Force (AIF), Methodist senior chaplain, encouraged H. J. Philpott, the Wesleyan resident chaplain in Cairo, to propose that Luxford go to the Anglo-Egyptian bank and obtain a guarantee of £500 to establish a Methodist soldiers’ home by renting the former Italian Embassy in Cairo at £220 per annum.32 Luxford understandably ‘felt very annoyed at an attempt by a brother minister to inveigle [him] into a financial obligation’ and refused to cooperate.33

On a more positive note, Luxford could not resist the opportunity, like the troops, of sightseeing in Cairo. He was, after all, in the land of many biblical stories that he had only read about. These Cairo experiences abruptly ended when the Turks attempted to cross the Suez Canal, and by the end of January 1915 Luxford found himself with the troops in a real fight. The experience was to contrast markedly with his time on Gallipoli. He travelled by train to the Suez Canal, slept clothed in the open, heard gunfire and found that ‘someone had pinched my fork and spoon so I have to make [my] pocket knife serve all purposes’.34 Luxford records two days later that Bob Dunnage, his orderly — later killed on Gallipoli — ‘has re-pinched my fork, spoon and knife that was pinched from me’;Luxford was clearly comfortable ignoring Dunnage’s misdemeanour.35 He enjoyed watching activities on the canal — warships using their searchlights at night, various ships passing all day, including a submarine, and aeroplanes flying overhead. Oblivious to danger, he rode on Laddie to Suez township and later to Port Tewfik, where he had a good lunch for 2s. 6d. at the Belle-Air Hotel. He even had time to watch a fisherman use a fine mesh to catch fish.36

Once the Suez skirmish ended, planning for the Dardanelles campaign escalated. Luxford now faced issues in his relationships with his commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel William Malone, and with three chaplains regarding representation at the front.

Luxford noted under the heading ‘officers regimental that I know — my own regiment Col Malone. Irish — a good soldier very quiet and reserved neither drinks, smokes nor tells stories. His hobby next to soldiering is photography. He comes from Stratford.’ On 27 February 1915, Luxford arrived at Zeitoun ‘to find orders out for denominational services’, signed by Malone.37 That was contrary to Godley’s determination to retain non-denominational services, but Godley had not promulgated the order. Luxford had a straight talk with Malone, whom he found ‘offensive and nasty’.38 Malone was particularly emphatic that ‘every man has a right to go to a service of his particular denomination and cannot be compelled to go to any other’. Malone’s diary further stated:

On my order for such service Maj Luxford (Wesleyan minister) who claims to be Senior Chaplain of the Forces, saw me and objected to the order, and claimed the right to hold the combined service, and said I was squashing Gen Godley’s arrangements. Could he see the Genl? I promptly repudiated the squashing and told Luxford he was not to go near the Genl with any complaint behind my back. He could lodge a complaint through me, against me to my Brigadier and if he had any complaint against the Brigadier he could then go to the Genl through the Brigadier. Result he caved in, and the separate services were held, much I think to everybody’s pleasure except Major Luxford’s. He is quite unsuited for his job. I am going to keep him up to his regimental work. He runs about too much in Cairo and everywhere, except our own lines.39

Luxford described the next day as ‘the most unhappy Sunday I have had since leaving home’. His unhappiness was exacerbated by Malone, who replied to Luxford’s concern about holding a church service outside in a gale, saying that ‘a senior officer shall take it’.40 However, Captain McDonnell (10/1095), who got on well with Luxford, told him to hold the service in one of the mess tents. Luxford did not ‘cave in’ on interdenominational services, and privately complained to Colonel Chaytor, who told Luxford to write to Malone formally requesting to discuss the matter with Chaytor. Malone agreed. Luxford’s argument was not solely based on Godley’s instruction to retain non-denominational church services, but, as he explained to Chaytor:

If Malone’s idea was carried out I am not able to see Wesleyans in any other Regt. and that while Anglican Presby in my regt are marched away to their chaplains in other regts, I am debarred from having my men from those regt. What was sauce for the goose is sauce etc. Chaytor said it was all right. He would see him and put matters right.41

Matters were put right, but not before Malone told Luxford that he took exception to his YMCA work and his attending a Presbyterian rally at Cairo, as those were not regimental activities.

Luxford, fearing a protracted argument, had also obtained the support of five other chaplains.42 He wrote in his diary what a ‘Pity that when on the verge of war such tactics should be used. Malone took advantage of the omission of order from Div H Quarters to have this row.’43 When Luxford again approached Malone to offer assistance with the burial of Bethel Simpson (10/941), he found Malone ‘rather stiff’ and the offer was rejected. Malone stated that his ‘CO would deal with it and make such arrangements in the future’.

To both men’s relief, Godley had Luxford transferred to the Otago Battalion and Father McMenamin transferred to the Wellington Battalion. Luxford wrote:

For many reasons I am glad to leave the Wellington Regt. First I don’t like Malone who declines to acknowledge [me] as any other than [a] Methodist chaplain … I get on well with the men and most of the officers. Some are gruff and rude, especially 2 of the Majors. They are not genial comrades. I think I shall be happier with Otago men.44

Malone, a staunch Roman Catholic, wrote that:

Fr. McMenamin is now our Chaplain in lieu of old Luxford, who is transferred to Otago Bn. Everybody is glad. He (Luxford) ought to have been left at the base. He is a useless specimen of an army chaplain, but has curried favour with the Genl and others. Young active amicable and amiable parsons left behind and he the reverse of those things taken to the Front.45

They would meet up again at Lemnos when Luxford visited the Itonus, looking for letters from home, and again on Gallipoli when Malone sought assistance regarding the burial of Lieutenant Hugo.46 According to Luxford, on both occasions Malone was a ‘changed man’ — gracious and genial.47 Malone was probably more preoccupied with military matters, and perhaps even he was not prepared to challenge Godley’s authority on the issue of chaplains’ roles or suitability.

In March 1915, Luxford’s relationship with the other chaplains reached a new low when it was revealed that only six would be going to Gallipoli.48 Luxford had agreed on this allocation with Godley. While four of the chaplains remaining in Egypt — Thornton, Clarkson, Greene and King — took the news with equanimity, Dobson and Ross immediately resigned to join the ranks, and Blamires was very unhappy; representing the church at the front was important for chaplains. However, it seems likely that some of those remaining behind were not fit enough. Certainly Clarkson, Thornton and Blamires had been hospitalised in Cairo for various illnesses and injuries.49

While Luxford described the chaplains’ resignations as the result of ‘the impatience of youth’, Bush-King intervened and sought Godley’s approval to allow Dobson to withdraw his resignation.50 Bush-King explained ‘upon mature consideration he [Dobson] now realises that this [resignation] is incompatible with his ordination vows, and he regrets that his zeal for active service should have led him to take the steps he did’.51 Godley agreed. Ross’s resignation was also resolved when he was given a temporary chaplaincy in the 5th Royal Fusiliers.

Luxford left Alexandria with the Otago Battalion on the Annaberg A27, a captured German cargo ship which had been roughly converted to carry troops to Lemnos and then to Gallipoli.52 Luxford wrote: ‘I find the Regt. very different from Wellington. The language is not as foul and the officers are genial.’53 ‘Men on board are so respectful and all officers so considerate.’54 However, the ship was very crowded and dirty; the crew were Greek and did not speak English; ship notices were in German; and Luxford had an adverse reaction to the food — he thought he had been poisoned. Death remained a fellow traveller. Private Percy Bigwood (12/30) died on 22 April 1915 at No. 1 Australian Stationary Hospital, Lemnos, of pneumonia, and, as he was Church of England, Luxford arranged for Chaplain Taylor to bury him. At the funeral, Luxford thought ‘Taylor was rather abrupt.’55 Clearly resentment of Luxford’s role as senior chaplain and the influence on decisions about chaplains lingered. Service on the front lines would sort these attitudes out.

On board the Annaberg on 25 April 1915 off Gaba Tepe, Luxford wrote, ‘as I conducted services we heard the cannon’s roar. Heavens calm. Clear sky. The cannons [sic] roar is incessant.’56 One soldier, a printer’s fitter from Dunedin, noticed that Luxford’s sermon was interrupted by the appearance on deck of four grinding stones to sharpen bayonets.57 A prelude of events to come.

The horror of war on Gallipoli was immediate, as Luxford recorded:

3 pm. Came ashore in destroyer Beagle. Wounded everywhere. Sights appalling. I did what I could. It seemed so little. Poor fellow with eyes protruding. Another with bullet in throat. Men bleeding to death. Oh, what sights! I slept here there and everywhere. Rain came down. Poor Col Stewart is dead. We have lost heavily. I must leave the scenes for future description. Saw several dead. Many wounded are left, and dead are not yet brought in. Shrapnel bursting all around us. Men hit within 3 yards of me.58

For nearly four months Luxford recorded events in his diary and sent letters relating his frontline experience to the Reverend S. J. Serpell, former president of the Methodist Conference. These were published in the Methodist Times. On 14 May 1915, Luxford wrote:

Language cannot describe my experiences. I have witnessed the wounded by hundreds, and some of the scenes have been heartrending. For days I have seen pilgrimages of pain and death … With the exception of a sore foot I have not suffered, and think I can put in another month or two before I ask for Blamires to relieve me … Doubtless New Zealand has wept tears of bitter sorrow because of the loss of her brave sons, but she must rejoice for their bravery, endurance and patriotism. She has helped to cement the Empire with her best blood! … The noise, terrible in its fury, has been incessant for nearly three weeks. We have not been able to gather in hundreds of our dead, nor dare we stand in groups for fear of snipers, who, in addition to the trained forces of the enemy, are scattered about, making sad havoc.59

His diary entry for 24 May 1915 described the armistice:

An armistice from 7.30 – 4.30 applied for by Turks and granted. I rose early, bathed and breakfasted then at 9.30 went with burial party of 100 Canterbury under Capt Brown and Lieut Lawry to bury the dead. Raining, climbed greasy hill 500 feet. Most doctors there. It was a battle armistice. Trenches only 20 yards apart. About 140 dead bodies between. About 30 of ours and Australians and over 100 Turks. Some had been lying there for a month. Corruption very marked. Decomposition indescribable. It was impossible to identify any except by discs and books. The burial party of Turks was there with Crescent on arms. We had red cross or white sash on arms. Markers of both sides stood in line and neither party crossed it. Officers talked through interpreters. No friendly chit-chat. All very formal. Rifles were exchanged with bolts taken out. A few decomposed bodies were handed over to the Turks, the rest were buried in a long trench or in a grave dug alongside. McMenamin, Grant and I were kept busy. We went from grave to grave. I recited the service over 15. Grant about the same. McM also had a few. It was gruesome. The burial party had to cover their nostrils and smoke. Every few minutes we washed our hands with disinfectant. In several instances the bodies could not be touched and we covered them with earth. I never saw decomposition so repulsive. I buried young Dustin of Wanganui. In some of our sap trenches men’s feet were protruding. Earth thrown over dead bodies. Graves everywhere. In one case 9 bodies had been placed in one grave.60

Luxford’s letters to Serpell recounted his close escapes from bullets, bombs and shrapnel; his praise for the work of doctors and stretcher bearers; the services he held with wounded soldiers awaiting transfer to hospital ships; and the church services held with the men. He felt a strong obligation to send to New Zealand ‘all the encouraging news’ he could, and Godley was keen for him to do so even if some of his letters sounded somewhat exaggerated. For example, ‘My heart has been touched at burials when the dead have been wrapped in a blanket or overcoat, and lain four and six in a grave and the comrades gathering the wild flowers that abound and reverently throwing them into the graves.’61

By June, Luxford admitted that ‘Camp life, with its marches, ceremonial parades and inspections, is as different from the battlefield as light from darkness’, and ‘Last night my own son was a victim — he was shot in the leg while in his dugout in the Auckland Mounted Regiment’s lines (there are no horses here; we are either infantry or artillery).62 I am thankful the wound is slight. I saw him off in ship to one of the base hospitals.’63 On 9 June 1915, Luxford was given leave and went with Chaplain Grant to Lemnos, but missed seeing his son, Frank, who had left for Alexandria.

Luxford described to Serpell one of the chaplains’ key battlefield tasks:

During the evening the chaplains detailed for duty ascertained the number of slain comrades in the mortuary. If a man be wounded, after first aid dressing, he is sent to a receiving hospital; if slain, his body is taken out of the trenches or from the field and reverently placed in a bomb-proof shelter, which is a small plot surrounded by sandbags and covered with canvas. We call it the mortuary. There are times when twenty and even forty bodies have been there … It is impossible, if we regard life, to bury our dead in the light. Why? Because all sheltered ground is required for bivouacing, so only exposed sites can be set apart for cemeteries. To bury up here in the day time would be wicked exposure to snipers. The burial party having reported, the chaplains led the way through saps or extended trenches, and then struck out at a double for the mortuary. Although dark the snipers kept up fire, and spent bullets fell, hence every precaution was necessary. In the mortuary, with the aid of an electric lamp or a match carefully covered, so as not to draw fire, we ascertained from identity discs the regiment or unit of our fallen comrades, making a note of the names and regimental numbers … Our burial party had been supplied with disinfectants, and … the bodies were lifted into transport carts about 11 p.m. We went down a gully for a mile or more till we reach the little cemetery, where there are some graves containing as many as thirty bodies … The party set to work in the three different sections and after grappling with roots and fibres, the graves were ready. The chaplains then removed the indentity [sic] discs, which next day they returned to the officer of the regiment to which the comrades belonged … The bodies were placed in the graves, and all kneeling as much under shelter as possible, we recited the service at each grave and offered a prayer for relatives far away, who will go through the dull cold agony of bereavement. We all prayed, we all sympathised. Then we marked the graves with stones or wooden crosses, leaving an understood sign for the site of the next grave, which, alas, will too soon be needed. The machine guns were firing, Japanese shells above us falling in enemy’s trenches. We marched back through trenches, saps and tracks. I reached my dugout at 2 a.m.64

In an attempt to preserve some normality, the first church service was held on 6 June 1915 in Pope’s Gully, and was attended by about 150 officers and men. The Red Cross contributed empty boxes for an altar. The officiating ministers were Chaplain Merrington (Presbyterian, Queensland), Chaplain Plane (Methodist, Queensland), the recently arrived Chaplain King (Presbyterian, New Zealand) and Luxford. Singing was not allowed because it would draw fire.65

On 21 June 1915, Godley ordered Luxford to return to Egypt to visit hospitals and suggest improvements. He was to act in ‘every way as the General’s Senior Chaplain’ and be responsible for the ‘appointments of chaplains of our NZ Division’.66 Godley also wrote to Lady Godley, asking her to get Frank to her convalescent home for New Zealanders in Alexandria. He finally confided to Luxford that ‘Chaplain Taylor has been mentioned in despatches, and that he was not mentioning his staff yet but later on there would be something more tangible and definite for some. I suppose I am to read between the lines.’67 Luxford was delighted.

This delight, however, soon changed when Luxford arrived in Alexandria on 3 July 1915 and discovered ‘bungling’.68 In his absence, chaplains had been ordered to join hospital ships and were not available when increasing numbers of wounded men from Gallipoli arrived in Egypt. A report from Blamires to Luxford highlighted the difficulty created by Luxford’s absence on Gallipoli. Decisions on chaplains’ work in Egypt were made by the military in consultation with Principal Chaplain Arthur Horden, Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF), but missed the ‘big picture’ of providing pastoral care and spiritual guidance for wounded soldiers arriving from the front. Blamires’s report, while respectful of

Luxford’s authority, must have been irksome for Luxford. He could not really quibble about Blamires’s actions because Blamires cited military authority in detail for his actions during Luxford’s absence.69 Luxford realised that he simply could not organise and direct chaplains from Gallipoli. This reinforced some of his misgivings about his senior chaplain nomenclature, and further confirmed that his influence originated from Godley. Luxford understood that having more chaplains on the ground would be ineffective, as they would not have enough to do. Individual chaplains left to themselves could not be relied upon to think strategically and deliver practical outcomes for their soldiers. Nor could the military authorities on the ground, as they had more pressing matters to deal with.

The lessons the report afforded were threefold. First, it confirmed to Blamires and the military authorities in Cairo that Luxford was ‘the man in charge’, as he had Godley’s direct support. Secondly, Luxford could not control or lead chaplaincy affairs from ‘the front’ any more than Godley could. Lastly, chaplains needed ‘management’, whether by Luxford or by the continuous presence of a ‘chaplain department’, with clear policies and processes. Later, Brigadier General George Richardson was appointed chaplain-general, based in London, to provide administrative control of all New Zealand chaplains, with advice from Luxford and direction by Godley. Chaplains were, in the first instance, military officers paid for by the government, a fact that some did not seem to grasp initially.

Luxford concluded his business in Egypt, met Arthur Horden, purchased various items for men on Gallipoli, and visited his son Frank at Lady Godley’s convalescent hospital and Chaplain Percy Clarkson in the deaconesses’ hospital. He returned to Mudros on 22 July 1915, and then Gallipoli on 27 July 1915. He debriefed Godley, who, to Luxford’s amazement, informed him that during his absence Chaplain Merrington, AIF, had tried unsuccessfully to get Godley to replace Luxford as senior chaplain. Luxford had been friends with Merrington, even sharing a dugout. The relationship changed after this news.

Luxford resumed his chaplain’s duties, and on 8 August 1915 he wrote:

The hill Chunuk Bair … the saddest day I ever spent. I feel utterly useless. Cannot get to the wounded up here. Cannot bury the dead and cannot make arrangements for my work. All are bent on one thing — Everything else is subservient — gaining the position … Many of the poor fellows will never come back … Hear that Col Malone is killed.70

The next day, he wrote: ‘Reports say that Wellington is practically wiped out. It is certain half our men are killed and wounded. We are short of stretchers. Some of the men are going down on their hands and sterns. Shot in both feet. Some are carried down. Blinded men are led down. This is a theatre of carnage.’71

On Thursday, 12 August 1915, Luxford recorded, in very shaky handwriting, his last diary entry:

I was struck with a bullet on Monday about 3 o’clock. It entered above my right knee and severed the principal artery. I bled profusely. I got to the ship and had some relief. My right leg is swollen and the doctor says it must come off. I don’t think there will be need for this — I should have loved to have seen you all again. I shall often be near you. God bless you Emmie.72

It no doubt came as a great shock to Emmie when she received a cablegram on 22 August 1915 with the words: ‘Life saved, leg amputated, out of danger.’73 Colonel Chaplain James Green, AIF, picked up the story about Luxford’s wounding during the attack on Chunuk Bair:

Mr Luxford was sitting down resting behind the firing line when a bullet struck him in the thigh and severed the artery. Though the blood was stopped at once, such a wound is always dangerous, even in the case of younger man. He was brought here in the Devanha hospital transport ship and taken to Victoria College Hospital [Alexandria]. The question was as to whether the leg should be amputated, as gangrene has set in at the foot. He was under the care of a leading London surgeon, Dr Boyd. Nevertheless, I thought it was due to him to obtain a second opinion before anything was done, and I asked for Sir Victor Horsley, a surgeon of worldwide fame. As a result of their consultation, it was agreed that in order to save his life the leg (the right) should be amputated. The operation was quite successful, and I learn to-day that he is considered to be quite out of danger.74

On 3 September 1915, Luxford left on HS Letitia for England, where he was admitted to the Endsleigh Palace hospital for officers. Reverend Joseph Smalley wrote to the Methodist Times that:

The operation was performed by one of England’s greatest surgeons, and has been pronounced by all experts who have seen the leg as a very fine piece of surgical work. The healing has been rapid and complete. But the patient has been suffering a good deal of spinal pain since reaching England. A nerve specialist, however, of high standing has declared it to be only superficial, and it is being quickly reduced by simple treatment, which has given the major much mental relief also. He expects in a few days to be transferred to another hospital in London (Roehampton) to be fitted with an artificial limb, and he hopes then to get about without serious difficulty. It may interest your readers to know that he arrived in London with no possessions but a pair of pyjamas and an overcoat, having lost all else in the confusion of the terrible time.75

Luxford was visited in hospital by Thomas Mackenzie, New Zealand High Commissioner; Lord Ranfurly, a former governor; the Reverend Bateson, secretary of the Wesleyan Army and Navy Board; and by a host of officers and men of the NZEF.

Luxford was mentioned in dispatches on 22 September 1915, received the Companion of Saint Michael and Saint George (CMG) on 3 June 1916 for outstanding services on the beaches of Gallipoli, and was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He requested to be posted to the New Zealand General Hospital, Walton-on-Thames, until the end of the war. This was agreed to, and he was joined there by Emmie and Gladys.76 On meeting him at Plymouth, Gladys ‘noticed how frail war worn my father looked & he walked with two sticks; but he was so happy to be able to still be of help to his beloved wounded men’.77 Luxford continued to provide valuable service to Godley and Richardson on the New Zealand Chaplains Department throughout the war. He arrived back in Wellington with Emmie and Gladys on 25 August 1919. His earlier dream had become a reality; he had survived and was home again after serving for over five years.

Luxford’s contribution to the war effort through his immense bravery and unwavering faith in God was well remembered by the men who had dealings with him. He conducted burial services in very exposed positions, even having to lie in the graves amongst dead bodies to escape being hit by bullets. On one occasion, Luxford forestalled the efforts of men trying to drag a wounded soldier into a trench with a lasso by carrying him into safety himself, despite a hail of bullets.

No one on Gallipoli worked harder. In addition to his spiritual ministrations, he carried out all manner of duties. When last seen by one soldier, he had his coat off and was toiling up a steep hill laden with ammunition. During the August Offensive, he occupied a dressing station near to the firing line, a very unsafe position just below Chunuk Bair, and did the work of more than one man of half his age. Minus his coat, with his shirt sleeves rolled up, he dressed and bandaged for hours at a stretch. Luxford was someone who ‘walked the talk’ in demonstrating his faith, and set the bar high with his own behaviour. He helped redefine chaplaincy policy, and was a catalyst in getting chaplains to adopt a more interdenominational approach when engaging with the men. Most importantly, he left behind his diaries, which are a national treasure.

War changed Luxford, not just physically but mentally. On his return he spoke forcefully from the Pitt Street Methodist pulpit in Auckland about his beliefs. He no longer supported military training camps and thought military discipline needed major revision. He endorsed the League of Nations in its bid to facilitate world peace, arguing that war was an abomination that required eradication. Newspapers keenly reported his views. Some in the military were seriously concerned, and many letters were written to defence headquarters asking what would be done about it. Nonetheless, Luxford was promoted in 1920 to chaplain class 1 with the honorary rank of colonel. He was, however, terminally ill by the time he arrived back in New Zealand, although his illness was unconnected to his war service; he had been diagnosed with cancer while at Walton-on-Thames. The army paid for his treatment, but Luxford died of prostate cancer at his home, ‘Chunuk Bair’, in Auckland on 28 January 1921, aged 66.78

In 1916, at Luxford’s suggestion, Albert Lawry, president of the Methodist Conference, had sent a letter to every Methodist in the NZEF, thanking them for their contribution to the war effort. The letter ended with the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson, which equally apply to Colonel John Aldred Luxford, CMG, MID, New Zealand’s highest-decorated military chaplain:

Not gold but only men can make

A people great and strong;

Men who for truth and honour’s sake

Stand fast and suffer long.

Brave men who work while others sleep

Who dare while others fly

They build a nation’s pillars deep,

And lift them to the sky.79

Notes

1 I acknowledge the support of the Luxford family in telling this story, and the valuable contributions of Joanna Hyslop, granddaughter of Chaplain Charles Dobson, Griere Cox, and my wife, Penny.

While Luxford’s first name was William, he never used it and preferred John. He was named after the Methodist minister Reverend John Aldred; Diary: John Luxford, Book 4, 12 January 1915, MS-4454-1, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington (hereafter ATL).

2 New Zealand Methodist Times (hereafter NZMT), 22 August 1914, p. 8.

3 Ibid., 3 October 1914, p. 10.

4 Following the lead of the imperial authorities, the 1911 New Zealand Census was used to calculate the proportional representation of chaplains according to the percentage of adherents of each denomination to the total New Zealand population.

5 Diary: John Luxford, Book 1, 28 October 1914, MSX-3468, ATL.

6 Military Personnel File: John Aldred Luxford, W5515, 0006399, Archives New Zealand, Wellington (hereafter ANZ); New Zealand Herald, 29 September 1881, p. 5.

7 Press, Christchurch, 29 April 1902, p. 5; Otago Daily Times, 5 September 1902, p. 5.

8 Order 172: ‘It should be clearly understood by all Chaplains of the forces now serving that the “honorary rank” mentioned in paragraphs 81 and 107 General Regulations is not to be taken as conferring military rank of any degree. Chaplains hold their appointments to the Force only, and are given status (but not rank) according as they are chaplains fourth, third, second and first class, and there are no appointments as Captain Chaplain, Major Chaplain &c.’ Correspondence: Godley to Allen, 19 July 1912, WA 252 1/[1], ANZ.

9 Military Personnel File: John Aldred Luxford, Luxford to Colonel E. W. C. Chaytor, 29 May 1912, W5515, 0006399, ANZ. Chaytor was sympathetic.

10 Luxford got advice from Sir Joseph Ward on the matter, and used Wanganui MP W. A. Veitch to raise the issue with Allen; Military Personnel File: John Aldred Luxford, Memorandum by Colonel G. C. B. Wolfe, Adjutant-General, 2/3 on behalf of Godley, W5515, 0006399, ANZ.

11 His wife, Emma Allen Mansfield (‘Emmie’) née Aldred (1857–1952), his children John Aldred (1881–1977), Maude Emmie (1882–1969), Frank Mansfield (1885–1956) and Gladys Violet (1888–1988).

12 ‘&’ (for ‘and’), ‘Xtianity’ (for ‘Christianity’), ‘&c’ (for ‘etc’).

13 For example ‘redtapeism’. Diary: John Luxford, Book 1, 24 October 1914, MSX-3468, ATL.

14 Ibid., 30 October 1914.

15 Luxford was very conscious of the importance of maintaining security, even regarding letters received by him. On 24 July 1915, on his way back to Gallipoli from Egypt, just past the Aegean island of Patmos, he wrote: ‘Could not bear to burn Emmie’s letters so threw them into the sea. I hate parting with the letters but it is impossible to carry them about.’ Diary: John Luxford, Book 12, MS-4454-3, ATL.

16 Otago Witness, 29 September 1915, p. 11. Luxford sent four spent shrapnel shells from Gallipoli to his wife in Christchurch, and they were placed on display in the lobby of the House of Representatives. Luxford wrote: ‘Each shell to me has a history, so I value them. I think they will be among the first, if not the first, to reach New Zealand. Of course they are only a few of thousands from the Turks that have killed and wounded so many of our brave boys. One of the shells (the smallest) fell within three yards of my dugout on a Sunday morning. You will find that experts conclude from the marks on this one that the gun is the worst for wear and tear.’ The shells are evidently of Turkish manufacture, as they bear Turkish hieroglyphics. The small one to which Luxford refers has several indentations on the casing, which indicates the worn condition of the mechanism of the gun from which it was fired.

17 William Cowper (1731–1800), an English poet and hymnodist.

18 Diary: John Luxford, Book 1, 2 November and 6 November 1914, MSX-3468, ATL.

19 The 10 other deaths were: John Campbell (10/1028), Albert Cooper (10/380A), Ernest Yoxall (E231 or 4/231A), George Burlinson (11/8), Henry Rayfield (6/125), William Ham (6/246), Bethel Simpson (10/941), Douglas Hewitt (12/947), Samuel Peed (2/1077) and Percy Bigwood (12/30).

20 The entire fleet stopped for Gilchrist’s burial at sea, with Ruapehu taking centre stage and the chaplains on all transports holding simultaneous services. The cause of death, revealed during a medical enquiry held in Albany, was not, as the men thought, a vaccination reaction. Military Personnel File: Jack Gilchrist, W5539, 23/0044719, ANZ; Troopship SS Ruapehu, AD1 786 25/19/25, ANZ.

21 Diary: John Luxford, Book 1, 20 November 1914, MSX-3468, ATL.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid., 6 December 1914.

24 Ibid., 2 November 1914.

25 In particular, Lieutenant Colonel P. C. Fenwick (3/158A) and Captain C. H. J. Brown (15/14), MID, respectively wounded at Gallipoli on 5 June 1915 and killed in action at Messines on 8 June 1917.

26 Diary: John Luxford, Book 3, 6 January 1915, MS-4451-1, ATL.

27 Ibid.

28 For example, details regarding Gilchrist’s death, troop destinations, the identity of the German commerce raider Emden, MID for Taylor, etc.

29 Diary: John Luxford, Book 2, 2 January 1915, MSX-3469, ATL.

30 The ‘enemy’ referred to was the traffic in drink. NZMT, 14 November 1914, p. 1.

31 Diary: John Luxford, Book 1, 11 December 1914, MSX-3468, ATL.

32 James Green (1864–1948) was not liked by Luxford, who felt that he was only motivated by self-interest and publicity-seeking. These sentiments were shared by other New Zealand and Australian chaplains.

33 Diary: John Luxford, Book 1, 18 December 1914, MSX-3468, ATL.

34 Diary: John Luxford, Book 6, 31 January 1915, MS-4454-2, ATL.

35 Private Robert Gordon Dunnage (10/113), Wellington Infantry Regiment, killed in action, 8 May 1915; Diary: John Luxford, Book 6, 2 February 1915, MS-4454-2, ATL.

36 Diary: John Luxford, Book 6, 25 January to 10 February 1915, MS-4454-2, ATL.

37 Diary: John Luxford, Book 8, 27 February 1915, MS-4454-2, ATL.

38 Ibid.

39 John Crawford with Peter Cooke (eds), No Better Death: The Great War Diaries and Letters of William G. Malone (Auckland, Reed, 2005), pp. 132–3.

40 Diary: John Luxford, Book 8, 28 February 1915, MS-4454-2, ATL.

41 Ibid., 2 March 1915.

42 These were George King (Presbyterian), John Ross (Presbyterian), William Grant (Presbyterian), Guy Thornton (Baptist) and Henry Blamires (Methodist).

43 Diary: John Luxford, Book 8, 2 March 1915, MS-4454-2, ATL.

44 Ibid., 3 April 1915.

45 Crawford with Cooke (eds), op. cit., p. 149.

46 Lieutenant Laurence William Albert Hugo (10/7), killed in action on Walker’s Ridge, 27 April 1915.

47 Diary: John Luxford, Book 9, 2 May 1915, MS-4454-3, ATL.

48 The six chaplains were William Grant, Patrick Dore, Charles Bush-King, John Luxford, James McMenamin and Thomas Taylor.

49 Diary: John Luxford, Books 2–8, ATL; Diary: P. W. Clarkson, MS-6660-1-2, ATL; Diary: H. L. Blamires, Knox College, Dunedin.

50 Diary: John Luxford, Book 9, 6 April 1915, MS-4454-3, ATL.

51 Correspondence: Bush-King to Godley, 7 April 1915, ANZ.

52 Annaberg was hit on 3 May 1915 by a Turkish warship firing on transports in the straits. Damage was minor.

53 Diary: John Luxford, Book 9, 11 April 1915, MS-4454-3, ATL.

54 Ibid., 18 April 1915.

55 Ibid., 24 April 1915.

56 Ibid., 25 April 1915.

57 Private Lesley Herbert Latimer (8/892), wounded 25 May 1915. Survived the war.

58 Lieutenant Colonel Douglas Macbean Stewart (6/1171), Canterbury Infantry Battalion, MID, killed in action 25 April 1915; Diary: John Luxford, Book 9, 25 April 1915, MS-4454-3, ATL.

59 NZMT, 24 July 1915, p. 10.

60 Diary: John Luxford, Book 9, 24 May 1915, MS-4454-3, ATL.

61 NZMT, 7 August 1915, p. 10.

62 Ibid.

63 Ibid.; Private F. M. Luxford (13/380) received a gunshot wound on 31 May 1915. He returned to New Zealand on the SS Tahiti, recuperated, returned to fight and survived the war.

64 NZMT, 21 August 1915, p. 10.

65 In 1929, Chaplain Ernest Merrington (Presbyterian) became the Master of Knox College, Dunedin. He died in New Zealand in 1953.

66 Diary: John Luxford, Book 12, 21 June 1915, MS-4454-3, ATL.

67 Ibid.

68 Ibid., 13 July 1915.

69 Blamires’s report is also useful because it highlights the Methodist Church’s infrastructure regarding the treatment of financial contributions from New Zealand, and the church committees set up to manage such donations.

70 Diary: John Luxford, Book 13, 8 August 1915, MS-4454-3, ATL.

71 Ibid., 9 August 1915.

72 Ibid., 12 August 1915.

73 NZMT, 4 September 1915, p. 1. Medical evidence indicates that it took two attempts to ligate the femoral artery, because of Luxford’s age. His leg was amputated above the right knee.

74 Sir Victor Alexander Haden Horsley, FRS (1857–1916) had been posted in May 1915 to head the British Army Medical Service in Egypt based at the 21st General Hospital in Alexandria. He died aged 59 years on 16 July 1916 of heatstroke on field surgery duty in Amarah, Iraq. Luxford was fortunate to have such a skilled surgeon; NZMT, 16 October 1915, p. 12.

75 NZMT, 11 December 1915, p. 5.

76 They departed Wellington on SS Rotorua on 4 February 1917.

77 Memoir: Gladys Violet Luxford, ‘How I Came to be Interested in War & Why I Went to WW1’, MS 94 6, Auckland War Memorial Museum, pp. 3–4.

78 For years the assumption was that Luxford died from his war wounds. His death certificate records ‘Carcinoma of prostate gland — 3 years’ as the cause of death.

79 Lyttelton Times, 23 May 1916; Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–82), American essayist, lecturer and poet.