German mountain soldiers in Greece.

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-163-0319-03A)

THE SHADOW OF OLYMPUS

THE ROAD TO SALONIKA

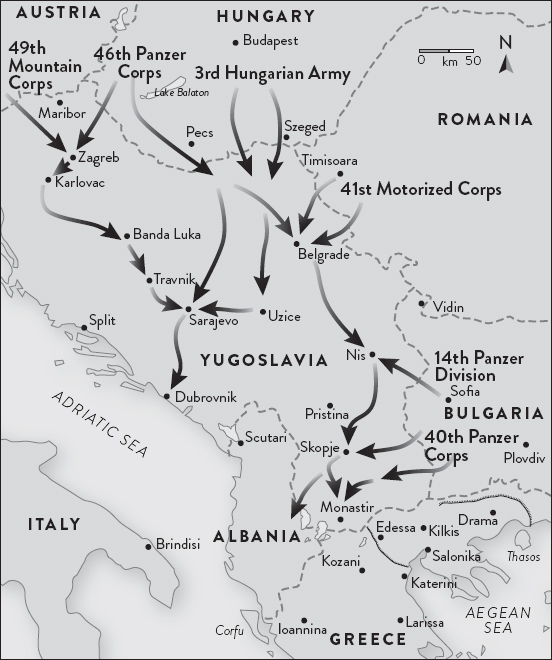

On 6 April 1941, Germany invaded Yugoslavia and the Luftwaffe conducted a massive terror-bombing raid on Belgrade, killing 17,000 inhabitants and destroying half the city. The 2nd Army attacked Croatia from Austria and Hungary while the 41st Motorized Corps and the 1st Panzer Group invaded Serbia from Bulgaria. The Italian 2nd Army crossed the Julian Alps into Yugoslavia and advanced along the Adriatic coast towards Ljubljana.

Meanwhile, Field Marshal Wilhelm List’s 12th Army invaded southern Yugoslavia and Greece from Bulgaria. The 40th Panzer Corps, commanded by General Georg Stumme, rolled into Serbia and advanced towards Skopje and the Monastir Gap, the gateway to central Greece. Stumme’s panzers overwhelmed the 7th Yugoslav Division as the Luftwaffe relentlessly bombed the retreating Yugoslav columns. By evening, his men had reached the Axios River.1 General Otto Hartmann’s 30th Infantry Corps attacked the eastern sector of the Metaxas Line along the Aegean coast. The 164th Division attacked Fort Echinos, but fierce Greek resistance halted their advance while the 50th Division advanced towards Komotini and encircled Fort Nymphaea.2

General Franz Boehme’s 18th Mountain Corps assaulted the Metaxas Line near the Rupel Gorge. The 5th Gebirgsjäger Division, mountain infantry armed with light artillery and howitzers, assaulted the forts at Rupel, Istibei and Kelkayia, but despite heavy artillery bombardment and airstrikes from Stuka dive-bombers, the Greeks defenders repulsed the invaders.3 The 6th Gebirgsjäger attacked the line at Demir Kapou and Kale Bair while the 72nd Division attacked three forts, but by the end of the day, the Germans had only captured one fort in the Struma Valley. The Wehrmacht had underestimated the Greek defences as Balck freely acknowledged:

On the German side our knowledge of the layout of the Metaxas Line was nebulous at best. German and Bulgarian intelligence had failed completely to identify the improvements that had been made to the positions. Had we known all that in advance, we most likely would have developed a different scheme of maneuver.4

German mountain soldiers in Greece.

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-163-0319-03A)

As the mountaineers assaulted the Metexas Line, the 2nd Panzer Division, also part of the 18th Mountain Corps, invaded southern Yugoslavia from Bulgaria. List had ordered Major General Rudolf Veiel to race through the Doiran Gap into the Axios Valley and capture Salonika.

The 2nd Panzer Division flanks the Metaxas Line, 6–8 April 1941.

The 3rd Panzer Regiment, at the forefront of the invasion, crossed the Serbian frontier. ‘On 6 April at 0520 hours we were at the ready,’ Balck recalled. ‘The Yugoslavian border guards had fled and the Bulgarian border guards were happily shooting into the air, waving us through.’5 Balck’s panzers advanced west through the Strimoll Valley, encountering little resistance:

Once we got across the border the roads usable for tanks ended. I had to get in behind our right column, which had been advancing faster on improved roadways and already had destroyed the Yugoslav 49th Infantry Regiment, capturing two hundred prisoners and sixteen guns. There was hardly any resistance.6

The harsh terrain and weather caused further delay as rain had transformed dirt roads into pools of mud. Balck’s men took two hours to pull their vehicles through:

I had driven ahead and was sitting in the middle of a field waiting for everything to close up. Slowly the first vehicle, then the first Panzer emerged from the mud, as the regiment followed piecemeal. Fortunately, there was no enemy. Salonika was close, but the damned mud near the border had slowed us down.7

Despite delays caused by demolitions, minefields and mud, the regiment reached the town of Strumica, its objective for the first day of the campaign, where resistance stiffened. The men encountered a deep anti-tank ditch and concrete obstacles defended by determined Yugoslav soldiers from the 3rd Army armed with machine guns and anti-tank guns. Balck noted the strong resistance his men faced in his after-action report:

The lead platoon of Leutnant Brunenbusch opens fire on the enemy, who has taken positions on the opposing slope in a dense thicket. The remaining platoons sheltering in the trench are trying to find a crossing, but cannot proceed. One tank after another hits a mine and is disabled. Due to the dense thicket, use of these weapons is impossible.8

German engineers, covered by fire from supporting panzers, flak and machine guns, created a path through the minefield and used explosives to demolish the anti-tank obstacles, allowing the motorized infantry to overwhelm the Yugoslav defenders and the panzers to resume their advance. The regiment encountered further Yugoslav resistance outside Strumica after a reconnaissance team and two Panzer IV medium tanks crossed a bridge. Balck observed the assault: ‘One tank “conquers” a gun emplacement. Single enemy positions in houses, from which the battalion commander is fired at, are silenced by some HE rounds.’9 By evening, the 2nd Panzer Division had reached the Axios Valley near the Greek border, south of Lake Doiran.

General Alexandros Papagos received reports of the German attacks on the Metaxas Line and southern Serbia. He requested a Yugoslav counter-attack against the 2nd Panzer Division’s flank as it advanced towards the Strumica Valley.10 Although the Yugoslavs attacked, their forces lacked strength and the Germans repulsed their assault without difficulty.

Papagos also ordered the Greek 19th Motorized Division, commanded by General Nikolaos Liubas, to stop the panzers east of Lake Doiran. The division, which guarded the eastern shore of the lake and the Greek– Yugoslav frontier near the Axios River, had earlier fought on the Albanian front and possessed an odd assortment of captured Italian Fiat tanks, ten British Vickers light tanks and several dozen Bren gun carriers.11 The poorly equipped division, which in reality was only brigade strength, defended 30 kilometres (18.5 miles) of front and was the only Allied unit between the 2nd Panzer Division and Salonika.

German artillery in Greece.

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-163-0319-07A)

The Luftwaffe bombed the port of Piraeus near Athens that night, damaging the ammunition ship SS Clan Fraser which later exploded. The blast also destroyed six merchant vessels, twenty smaller ships, harbour infrastructure and nearby trains. The damage to the port would create supply problems for the Allies for the rest of the campaign because they now had to rely upon smaller ports such as Khalkis, Stilis and Volos.12

On 7 April, Balck advanced unopposed through the Axios Valley ‘over the winding mountain pass, crossing countless bridges’, but roads cratered by explosives caused delays. ‘Our pioneers work continuously,’ he noted. ‘Later this day, 12 Serbian tanks are surprised and all are destroyed.’13 After sunset, Balck slept in his Volkswagen Kübelwagen command car until bright headlights from two vehicles broke his slumber:

I thought that they must be out of their minds, driving around like that in the middle of a war. I woke up the regimental clerk and told him, ‘Go straighten them out, will you?’ As he stood right in front of the lead truck I could hear shouting and confused voices. I was out of my vehicle in a flash and immediately realized that I was standing in the middle of a Greek company.14

Balck and five soldiers from his headquarters staff realized they were surrounded by sixty enemy soldiers. He boldly walked towards the Greek soldiers: ‘I pulled my pistol, instinctively grabbed the rifle from the first Greek soldier, and started yelling at them. That did it. The Greeks immediately formed up, standing at attention.’15 Balck’s staff took the Greek troops prisoner.

Further east, the German divisions continued their assault on the Metaxas Line. The 5th Gebirgsjäger captured three forts while the 6th Gebirgsjäger breached the line and reached the railway to Salonika in the evening.16 The 72nd Division advanced through the Yiannen Valley and penetrated the line south of Nevrokop, threatening to envelop the Rupel Pass.17 The 30th Infantry Corps bypassed the Greek forts at Echinos and Nymphaea as soldiers from the 50th Division marched towards Salonika and the 164th Division advanced east towards Alexandroupolis.18

On 8 April, the 30th Infantry Corps reached the Aegean coast after overcoming strong Greek resistance. The 164th Division captured Fort Echinos and occupied Xanthi while the 50th Division advanced towards the Nestos River. The 5th Gebirgsjäger attacked Fort Rupel, but the defenders repulsed their assaults, inflicting heavy casualties on the mountain troops.

Meanwhile, the 2nd Panzer Division advanced south towards Lake Doiran, crossing the Greek border before advancing towards Akritas. The German advance guard, supported by the Luftwaffe, overwhelmed the Greek 19th Motorized Division, which had no means of conducting an adequate defence. By midday, the Germans had captured Akritas and forced the Greeks to retreat from the high ground at Obeliskos.19 The advance guard continued towards Kilkis while the survivors of the 19th Motorized Division retreated southwards after General Lioumbas ordered his men to withdraw. The panzers resumed their advance through open country towards Salonika.

The 3rd Panzer Regiment, which did not participate in fighting near Akritas, followed the vanguard through the Doiran Gap and the Axios Valley. Balck once again struggled against the elements:

I had managed to get the tanks, one rifle company, and one battery out of the mud. By that point the ground in the mud patch had been torn up so completely that nothing else could move. With the small force I had available I pushed on via Kilkis toward Salonika.20

As Balck’s regiment slowly advanced towards Kilkis on the road to Salonika, General Konstantinos Bakopoulos, commander of the Eastern Macedonian Army, received reports of panzers advancing through the Doiran Gap, which threatened Salonika and the Metaxas Line. He consequently ordered a general withdrawal towards the Aegean ports.21 At night, Bakopoulos sent an envoy to the 2nd Panzer Division to propose a regional ceasefire with a caveat that Greek soldiers could retain their weapons. However, he stressed to his commanders that they were honour bound to continue resisting until a ceasefire had been signed. General Veiel, after signalling the terms of the proposal to List, agreed to the ceasefire, which would begin in the morning, although the question of the Greeks retaining their arms would be settled later during negotiations.22 Balck believed that Bakopoulos had lost his nerve because the Eastern Macedonian Army could have held out longer:

. . . the situation for the Greeks at that point was not that unfavorable. They still held considerable sectors of the Metaxas Line and especially the important Roupel Pass. The Greek commander did not really know what was moving against Salonika. In fact, it was only elements of a division whose main body was still far behind at the border, stuck in the mud. Our Panzers positioned near Salonika only had gas for a few more kilometers, not enough for a real fight. No supplies would make it forward for forty-eight hours. Would the Greeks still have surrendered if they had known all that? The old adage is never to give up in war; the enemy is at least as bad off as you are.23

The 2nd Panzer Division entered Kilkis just before midnight and Balck noted, ‘After a speedy ride we reach the gates of Thessaloniki [Salonika].’24 The panzers had advanced through harsh terrain which, as List explained, was a remarkable achievement:

With infinite pains and after a number of tanks had been eliminated for technical reasons, the formation overcame mountains, boggy paths and inundated country and reached open country south of the mountains with still enough tanks to be capable of the decisive breakthrough towards Salonika.25

On the morning of 9 April, the 2nd Panzer Division rolled unopposed into Salonika, encircling the Metaxas Line. As panzers paraded through the streets, Balck witnessed a strangely festive populace:

The world had gone totally crazy. The city was packed with people shouting, ‘Heil Hitler, Heil Hitler, Bravo, Bravo!’ Flowers were thrown into our vehicles. All hands were raised in the Hitler salute. Were we occupying an enemy town, or were we returning back home to a victory parade?26

In the early afternoon, the Eastern Macedonian Army formally capitulated after Bakopoulos signed a surrender document in Veiel’s presence at the German Consulate. As the ceasefire came into effect, the remaining Greek forts on the Metaxas Line surrendered and the Germans took 60,000 prisoners and, as Balck explained, ‘we had to deal with the traditional ethnic and national hostilities of the Balkans. During the surrender the Greeks specifically requested not to be handed over to the Italians or the Bulgarians.’27 The commander of the 72nd Division congratulated the Greeks on their courageous defence of their forts, declaring that he had not witnessed such stubborn resistance in Poland and France.28 Balck shared his high opinion of the valiant Greeks:

Overall the Greek troops had fought brilliantly and quite tenaciously. They had been the toughest of all of our adversaries so far. They even fired on diving Stukas with their rifles. Their fortifications were cleverly designed. The fighting was more difficult than for the Maginot Line.29

The battle for the Metaxas Line resulted in 1200 Greek casualties while 720 Germans had been killed and 2200 wounded.30

The 2nd Panzer Division captures Salonika, 9 April 1941.

In Yugoslavia, resistance in southern Serbia disintegrated as the 40th Panzer Corps destroyed the 3rd Yugoslav Army and captured Skopje in Macedonia. The SS Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler Regiment, the Führer’s personal bodyguard unit commanded by Josef ‘Sepp’ Dietrich, advanced into the Monastir Valley and captured Prilep, cutting the vital railway between Belgrade and Salonika, threatening the Monastir Gap. The next day, the Germans captured Nis and continued towards Belgrade while the Leibstandarte seized the Monastir Gap, opening another gateway into Greece.

The Fall of Yugoslavia, April 1941.

Weichs’s 2nd Army continued its advance across Yugoslavia, meeting only sporadic resistance as pro-German Croatian units mutinied, seizing Zagreb on 10 April where Croatian nationalists declared independence. Two days later, the 46th Panzer Corps captured Belgrade and, as the collapse of the country could no longer be prevented, the Yugoslav High Command asked for an armistice, which was signed on 17 April.

Lieutenant General Thomas Blamey (left), Lieutenant General Henry Wilson (centre) and Major General Bernard Freyberg (right).

(AWM)

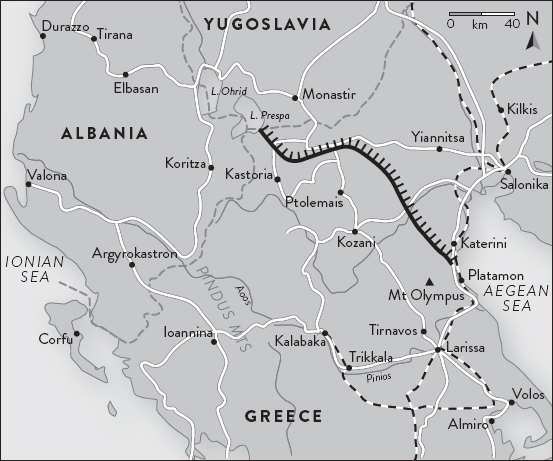

ABANDONING THE ALIAKMON LINE

As Germany invaded Greece on 6 April, Anglo-Greek soldiers defended the Aliakmon Line from the Aegean Sea to the Yugoslav frontier. The 2nd New Zealand Division, commanded by Major General Bernard Freyberg, defended the line from the Aegean to the northern foothills of Mount Olympus with the 6th Brigade in the coastal sector, the 4th Brigade in the west and the 5th Brigade in reserve at Olympus Pass. Freyberg, with insufficient troops, defended zones normally allocated to battalions with companies.31

Lieutenant General Thomas Blamey, commander of the 1st Australian Corps, realizing the weakness of the defence, advocated the immediate withdrawal of the 2nd Division from the Aliakmon Line to Olympus Pass. Lieutenant General Henry Wilson disagreed because a retreat would abandon the railhead at Katerini, the main supply route of the Greek Army in eastern Albania, and force the Allies to rely on the low-grade mountain road from Larissa.32 Freyberg agreed with Blamey and made preparations for a withdrawal to Mount Olympus, believing that Wilson would soon change his mind. Freyberg’s instincts proved correct when Wilson’s staff began drafting plans for a withdrawal to an ‘intermediate line’ from Olympus Pass to the Vermio Mountains.33 As the defeat of Yugoslavia seemed certain, Wilson decided to withdraw. The New Zealand troops on the Aliakmon Line would retreat from the Macedonian plain, abandoning much of their wire and mines by the anti-tank ditch they had spent almost a month preparing.

On 8 April, Papagos, realizing that the Germans could enter the heartland of Greece through the Doiran and Monastir gaps, decided to withdraw Greek forces from Albania in order to form a new line across the Greek peninsula. W Force would hold its ‘intermediate line’ while Greek forces defended the line further west from Lake Vegoritida to the Florina Valley at Vevi. Wilson planned to defend the ‘intermediate line’ long enough to allow Greek forces to withdraw from Albania and allow W Force to establish the ‘Olympus–Aliakmon Line’, further south from Mount Olympus to the Aliakmon River and south-west to Servia.34

Wilson meanwhile established a force at Vevi under Major General Iven Mackay based on the 19th Australian Brigade, which included the 1st Armoured Brigade, to defend Vevi and the Kleidi Pass. After Brigadier Harold Charrington ordered the 1st Armoured Brigade to withdraw back across the Aliakmon River towards the ‘intermediate line’, he reminded his men that as British soldiers would soon fight the Germans in Europe for the first time since Dunkirk, the world will be watching with ‘heartfelt interest’.35

As the 2nd Panzer Division advanced towards Salonika from the Doiran Gap, Papagos requested reinforcements from the 1st Armoured Brigade, but Wilson refused, having already decided to withdraw. Balck strongly disagreed with Wilson’s decision because W Force could have attacked the German flank while it was stuck in the spring mud on the road to Salonika. ‘Considering the condition of the division’s lead elements,’ he argued, ‘there was no doubt who would have been successful. But instead, the English corps just stood by without intervening as the East Macedonia Army Detachment was destroyed.’36 The lack of co-operation between Greek and British forces would plague the Allies for the remainder of the Greek campaign.

The New Zealand Sector of the ‘Aliakmon Line’.

As the 2nd New Zealand Division deployed to the ‘intermediate line’, the 4th Brigade moved towards Servia Pass while the 6th Brigade retreated south towards Olympus Pass. Freyberg also ordered the 21st New Zealand Battalion, from the 5th Brigade, to move north by train from Athens to defend the Platamon Tunnel on the Aegean coast, on the extreme eastern flank of the new line.37 The Allied plan to defend Mount Olympus seemed feasible, as Balck explained, given ‘the incredible defensive advantage of the mountainous terrain and the traditional toughness and courage of the British soldiers’.38

W Force’s ‘Intermediate Line’.

On 9 April, Wilson confirmed that the ‘intermediate line’ would consist of Mackay Force at Vevi, the 20th and 12th Greek Divisions in the Vermio Mountains, the 16th Australian Brigade at Veria, the 4th New Zealand Brigade at Servia and the rest of the 2nd Division at Olympus Pass.39 Mackay Force had to defend Vevi for as long as possible to allow the Greeks to retreat from Macedonia and Albania before eventually withdrawing south to the 4th Brigade position at Servia.

General Mackay placed Brigadier George Vasey in charge of defending Vevi where the Monastir Valley narrows into the Kleidi Pass with the 2/4th and 2/8th Australian Battalions, the 1st Rangers from the 1st Armoured Brigade, the 2/1st Australian Anti-tank Regiment, New Zealand machine gun detachments and two artillery regiments. Vasey planned to hold the northern entrance to the pass, south of Vevi village. The 2/4th Battalion moved into the hills on the left flank to defend Mala Reka ridge and the 2/8th Battalion guarded a ridge on the right flank. Vasey positioned the Rangers in the centre, south of Vevi, to defend the line behind a minefield, supported by the 2/1st Australian Anti-tank Regiment and the New Zealand machine gunners.

After the fall of Salonika, List believed that his 12th Army could swiftly advance into central Greece and destroy W Force before outflanking the Greek forces retreating from Albania. He ordered Boehme’s 18th Mountain Corps in the Aegean sector to advance towards Mount Olympus and Stumme’s 40th Panzer Corps to advance through the Monastir Gap and attack the Allied position at Vevi in order to drive a wedge between Anglo forces and the Greek Army in Albania. List intended both German thrusts to form a pincer towards the vital Allied supply base at Larissa in central Greece, which List judged would ‘be fatal to the Greek and British forces’.40 Stumme accordingly ordered his spearheads to advance to Vevi.

On 10 April, the Leibstandarte’s 2nd Reconnaissance Battalion linked up with the Italians advancing from Albania near Lake Ohrid while the bulk of the regiment advanced through the Monastir Gap. Its lead motorcycle column, followed by trucks and armoured cars, encountered a troop of three Marmon-Herrington armoured cars from the New Zealand Divisional Cavalry, which had entered Yugoslavia to delay the German advance by destroying bridges. After a brief firefight, the New Zealanders withdrew south towards the Kleidi Pass.

Stumme’s advance guard — Kampfgruppe Witt — a battlegroup drawn from the Leibstandarte’s 1st Battalion commanded by Major Fritz Witt, approached Vevi and probed the defences of the Kleidi Pass. The SS troops attacked the 2/8th Battalion’s position near Hill 997 while a reconnaissance platoon attempted to flank Mackay Force north-east of the village.41 As Allied artillery shelled German troops arriving on trucks, Witt decided to halt his attack and wait for more troops and heavy weapons to arrive. Kampfgruppe Witt halted as Australian soldiers watched enemy vehicle convoys and armour arriving from the north. The bulk of the Leibstandarte had arrived by dusk and, during the night, German patrols probed the Allied defences.

The Battle of Vevi, 12 April 1941.

The next day, Stumme planned to seize the Kleidi Pass, which would allow his panzer corps to cut the Allied retreat by linking up with units from the 18th Mountain Corps advancing through the Edessa Pass. The Leibstandarte, reinforced by tanks from the 9th Panzer Division and artillery, seized Vevi. In the early evening, Witt ordered his 7th Company, supported by two StuG III assault guns, to attack the high ground on the right flank of the 2/8th Australian Battalion. However, the attack stalled after defending artillery fire disrupted the German advance and the assault guns withdrew. Despite this setback, the infantry pressed forward and captured several forward posts before machine gun fire forced them to retreat to Vevi. After nightfall, Stumme planned a methodical attack to commence the next day. The 9th Panzer Division would attack the Allied line between Mackay Force and the 21st Greek Brigade, while Kampfgruppe Witt attacked the Kleidi Pass.

On the morning of 12 April, Witt’s 1st Company advanced towards the boundary between the 2/8th Australian Battalion and the 1st Rangers, supported by mortar and machine gun fire. Despite accurate Allied artillery fire and vicious hand-to-hand fighting, the German assault forced the Australian companies on the left flank to retreat up the ridge, but the battalion’s right flank stopped the German advance.42 The 1st Rangers witnessed the withdrawal of the two Australian companies and, believing that the entire battalion had been overrun, retreated. In the early afternoon, Kampfgruppe Witt launched an assault, supported by assault guns, which forced the Australian battalions to withdraw south and the Leibstandarte seized the Kleidi Pass.

Stumme now needed to capture Servia Pass before he could advance towards Larissa. The 9th Panzer Division advanced towards the pass while the bulk of the Leibstandarte headed west to Kastoria to destroy the 3rd Greek Corps and cut off the withdrawal of Greek soldiers from Albania.

Mackay Force withdrew towards Servia where the 4th New Zealand Brigade defended the pass, a naturally strong defensive position where the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I had built a castle in the sixth century AD. As the men retreated south, the rearguard delayed the German advance and Brigadier Charrington took personal command of the blocking force at Sotir along a stream, which consisted of two squadrons from the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment and one from the 4th Hussars. At dusk, a company from Kampfgruppe Witt contacted the rearguard, but the Germans stopped for the night on the opposite side of the stream. During the night, Stumme formed a battlegroup from the 9th Panzer Division and the 59th Motorcycle Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Willibald Borowietz, to advance through Witt’s troops towards Kozani in the morning, followed by the 33rd Panzer Regiment.43

On the morning of 13 April, Kampfgruppe Borowietz launched a series of unco-ordinated attacks against Sotir Ridge. Despite Allied artillery and machine gun fire, a small German detachment crossed the stream, but a squadron of Charrington’s tanks and the Rangers’ Bren gun carriers repulsed the German assault. After the rearguard checked the German advance, it withdrew to the second defensive position south of Ptolemais where a stream created a natural anti-tank ditch. The Rangers defended a ridge, the bulk of the 4th Hussars and a squadron of tanks guarded the right flank and a squadron from the 4th Hussars supported by anti-tank guns covered the left flank.

At midday, Kampfgruppe Borowietz and elements of the 33rd Panzer Regiment reached Ptolemais. In the early afternoon, German artillery shelled Ptolemais Ridge as panzers advanced towards the village.44 Allied artillery fire convinced the Germans to avoid a frontal attack. Just before nightfall, thirty-two panzers attempted to flank the rearguard and encountered Allied armour, initiating the only significant tank battle of the Greek campaign.45 After the rearguard destroyed six panzers, Charrington, realizing his force might be cut off, ordered a withdrawal to Servia Pass. The 1st Armoured Brigade had suffered heavy losses as the Germans knocked out at least six tanks and twenty-one others, after mechanical breakdowns, were destroyed by their crews, effectively wiping out the Allied armoured force in Greece.

As Mackay Force retreated south, Wilson decided to withdraw W Force to Thermopylae where ‘British Imperial troops could hold without reliance on Allied [Greek] support’.46 Although this would abandon all of Greece except the Peloponnese and Athens, Wilson did not consult with Papagos beforehand and the Greek general continued to plan the defence of the Olympus–Aliakmon Line.47 As Balck observed, ‘the English divisions were like rocks in the surf, refusing any kind of coordination with the Greeks’.48 Wilson’s main problem now was the need to hold the vital crossroads at Larissa, which his men would have to retreat through on the road to Thermopylae. Meanwhile in Cairo, Admiral Andrew Cunningham, the Royal Navy’s Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean, considered evacuating W Force from Greece. The Royal Navy consequently began preparations under the codename Operation Demon.

An RAF Blenheim in Greece.

(© IWM)

The RAF had attempted to disrupt the German advance but the Luftwaffe, possessing forward airfields, maintained air superiority over the battlefield and British bombers suffered heavy casualties. Air Vice-Marshal D’Albiac ordered his remaining planes to redeploy to Athens and by mid-April RAF strength in Greece was reduced to just twenty-six Blenheims, eighteen Hurricanes and twelve Gladiators.49 However, Balck argued that Allied air power could have been decisive in Greece:

I am convinced that the English could have completely stopped the German conquest of Greece if they had properly employed their air [force]. The roads were narrow mountain roads filled to overflowing with our columns. By hitting us at the right points they could have caused us boundless losses.50

The ‘Olympus–Aliakmon Line’.

On 14 April, a battlegroup created from the German 9th Panzer Division commanded by Colonel Hans Graf von Sponeck advanced towards Servia Pass. Kampfgruppe Sponeck occupied Kozani just before midday and continued towards the Aliakmon River, hoping to capture the pass before the Allies established a proper defence.51 In the afternoon, observation posts of the 4th New Zealand Brigade spotted German vehicles, including over thirty panzers, advancing south towards the river. In the early evening, elements of Kampfgruppe Sponeck crossed the river near a demolished bridge, but Allied artillery checked their further advance.

The planned withdrawal to the ‘Thermopylae Line’ via the Larissa crossroads.

THE ADVANCE FROM SALONIKA

After the fall of Salonika, the 3rd Panzer Regiment quartered in Nicopolis. As the men rested, Balck became transfixed by the majesty of Mount Olympus, home of the Greek gods:

When I opened my window in the morning I could see snow-covered Mount Olympus against the blue sky, hovering over the dense fog of the Warda Plains. It was overwhelming. I had seen a lot of the world. Nothing compared to Mount Olympus. So there I sat, pensively in awe, holding a copy of Homer that I had brought along. I never put him away while I was in Greece.52

Balck contemplated the next phase of the campaign after List ordered the 18th Mountain Corps to advance south towards Katerini and Mount Olympus. The 6th Gebirgsjäger would march from Veroia and climb the mountain’s northern slopes while the 2nd Panzer Division would cross the Aliakmon River and force the passes closer to the Aegean coast before converging on Larissa. Balck explained how German planning concentrated on capturing the town:

The Twelfth Army initiated the pincer movement against the British Expeditionary Corps. On the German left wing the 2nd Panzer Division was supposed to attack on both sides of Mount Olympus, with the 6th Mountain Division attacking across Mount Olympus, thrusting toward Thessaly. Larissa was the objective for all forces.53

After Boehme ordered the 18th Mountain Corps to advance south on 11 April, its forward reconnaissance elements moved through the Axios plain. The 6th Gebirgsjäger crossed the Vardar and Aliakmon rivers before commencing its ascent up the foothills of Mount Olympus.54 The 2nd Panzer Division waited for petrol resupplies and, the next day, Boehme ordered Veiel to advance south along the Aegean coast to Platamon and through Olympus Pass.

British soldiers in Greece.

(© IWM)

By 13 April, the 5th and 6th New Zealand Brigades planned to hold Olympus Pass to allow the remainder of W Force to withdraw through Larissa — the critical junction where all key roads from northern Greece converged. The retreat to the Thermopylae Line also depended upon the 21st New Zealand Battalion defending the narrow pass at Platamon between Mount Olympus and the Aegean Sea. If the Germans captured Larissa before the retreating Allied troops passed through, W Force would be doomed.

In the afternoon, the advance guard of the 2nd Panzer Division crossed the Aliakmon River near Nicelion.55 The next day, List reported that ‘the English have abandoned, apparently in panic, the positions in the Aliakmon bend east and SE of Verria prepared weeks ago’. He also noted that the 18th Mountain Corps ‘will advance on Larissa from its bridgeheads south and east of Verria with its main weight (2 Pz Div) going through Katerini’.56 Balck knew that his objective ‘was the destruction of the English forces, which would result in the conquest of all of Greece’.57