Although Germany produced a number of truly outstanding Panzer commanders during World War II, few were more successful or more accomplished than Hermann Balck.1

Carlo D’Este

Perhaps the most brilliant field commander on either side in World War II was Hermann Balck.2

Freeman Dyson

HERMANN THE OBSCURE

On 8 May 1945, the day World War II in Europe ended, General Hermann Balck presented himself to Major General Horace McBride, commander of the American 80th Infantry Division, in the Austrian town of Kirchdorf. Balck had come to arrange the surrender of the German 6th Army to American forces, desperate to ensure that his soldiers would not become prisoners of the Soviet Union. This act ended the career of an extraordinary panzer commander, although McBride and his victorious troops did not realize the importance of their new prisoner whose unfamiliar surname, Balck, meant nothing to them.

Balck had earlier established himself as one of the finest armoured warfare commanders in history during the Chir River battles, a series of desperate engagements fought on the frozen steppes of southern Russia during Germany’s disastrous Stalingrad campaign. On 8 December 1942, when commanding the 11th Panzer Division, he annihilated the Soviet 1st Tank Corps at Sovchos 79, destroying fifty-three Red Army tanks. One week later, with only twenty-five operational panzers, Balck attacked the Soviet bridgehead at Nizhna Kalinovski and destroyed sixty-five Russian tanks while only losing three panzers.

Balck’s extraordinary achievements at the Chir River earned him a well-deserved reputation within the Wehrmacht as a commander who led from the front and won battles despite fighting against overwhelming odds. The German High Command recognized his courageous leadership, awarding him the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds, a prestigious medal given to only twenty-six other Germans during World War II. General Heinrich Gaedcke, who served under Balck on the Eastern Front, remembered him as a ‘model field commander’ and a ‘man of unconventional, brilliant ideas and inspirations’.3

Despite Balck’s exceptional military record, he received little recognition after the war. Unlike Erwin Rommel, Heinz Guderian and Erich von Manstein, who will forever be associated in the popular imagination as legendary German commanders, history has largely forgotten Hermann Balck. The historian Carlo D’Este accordingly observed that his name ‘is conspicuously missing from the list of successful generals’.4 David Zabecki similarly concluded that Balck is the ‘greatest German general no one ever heard of ’.5

Balck’s obscurity in the English-speaking world partly resulted from the fact that he spent most of the war on the Eastern Front, distinguishing himself in battles unfamiliar to most westerners — the Kiev salient in 1943, Ternopil and Kovel in 1944, and the siege of Budapest in 1945. He only fought the Americans twice, at Salerno following the Allied invasion of Italy in 1943 and during the poorly remembered Lorraine campaign in 1944, when he opposed General George S. Patton.

Balck also contributed to his own obscurity by avoiding the spotlight after the war. While a prisoner in American custody, he refused to participate in historical work conducted by the United States Army’s Historical Division, unlike many former German generals who used this opportunity to inflate their own reputations. After being released in 1947, Balck worked in a warehouse to support his family and made no effort to publicize his past deeds. He remained silent when other Wehrmacht veterans wrote their memoirs, notably Guderian’s Panzer Leader and Manstein’s Lost Victories, which became bestsellers and ensured their post-war fame.

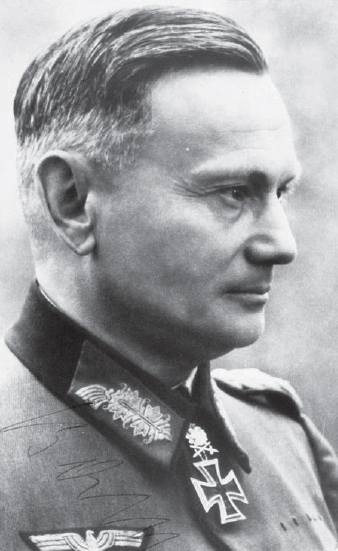

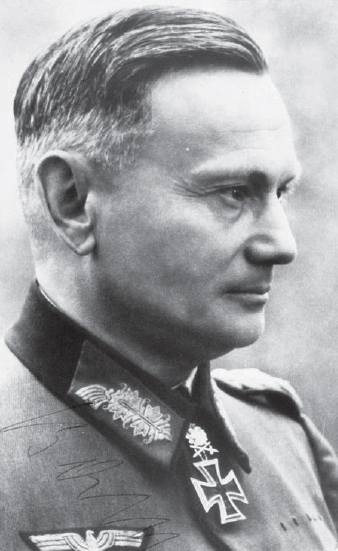

Hermann Balck.

(Author’s Collection)

The few histories which did mention Balck immediately after the war often portrayed him in an unfavourable light. Hugh Cole, in The Lorraine Campaign (1950), unfairly described him as ‘an ardent Nazi’ with a ‘reputation for arrogant and ruthless dealings with his subordinates’ who was just ‘the type of commander certain to win Hitler’s confidence’.6 Cole concluded that Balck was ‘an optimist’ who was ‘prone to take too favorable a view of things when the situation failed to warrant optimism’.7 Chester Wilmot in The Struggle for Europe (1952), clearly referencing Hugh Cole, similarly declared:

The command [of Army Group G] was given to General Hermann Balck, an experienced tank commander and a notorious optimist with a reputation for ruthless aggression. This appointment was not welcomed by von Rundstedt, for Balck had no experience of operations against the Western Powers. With Hitler, however, this was no doubt a point in his favour.8

Actually, Balck had fought the western Allies in France in 1940, Greece in 1941 and Italy in 1943. Despite such slander, his legacy slowly emerged from obscurity and distortion, initially due to the efforts of Friedrich von Mellenthin. As a General Staff officer, Mellenthin had served as an operations and intelligence officer in Rommel’s Afrika Korps before becoming Balck’s chief-of-staff in the 48th Panzer Corps on the Eastern Front. After the war, Mellenthin wrote Panzer Battles (1956), which became a bestseller, and in this book he defended Balck’s reputation and sought to correct the historical record. ‘I regret that in that remarkable work, The Struggle for Europe,’ Mellenthin explained, ‘Chester Wilmot has followed the estimate of Balck’s qualities given in the American official history, The Lorraine Campaign, where Balck is portrayed as a swashbuckling martinet.’9 Mellenthin countered such impressions and concluded: ‘If Manstein was Germany’s greatest strategist during World War II, I think Balck has strong claims to be regarded as our finest field commander.’10 Mellenthin also convinced Balck to end his long post-war silence.

After experiencing a devastating defeat in the jungles of Vietnam, the American Army sought to reform itself by refocusing on its traditional Cold War role of defending NATO against a feared Soviet invasion of Western Europe. However, in doing so it faced the dilemma of how to fight the Red Army and win despite being vastly outnumbered. The army’s leadership sought the solution to this problem by studying the Wehrmacht’s Eastern Front operations and accordingly invited Mellenthin and Balck to America where they became military consultants, participating in symposiums, conferences and wargames during the late 1970s and early 1980s. The Americans found themselves in awe of Balck’s first-hand accounts of his Eastern Front battles and General William E. DePuy, commander of Training and Doctrine Command, considered him to be ‘the best division commander in the German Army’.11 Balck’s advice strongly shaped the American Army’s AirLand Battle concept, which forms the basis of western military doctrine to this day.

Balck, through his engagement with the American military, gained a Sun Tzu-like reputation as officers frequently quoted his maxims as sage wisdom in their academic studies and military journals. In a typical example, Lieutenant Colonel Douglas Pryer declared in Military Review:

Moltke cemented the support that military culture, education, and training gave to what had become decentralized command. Schools gave extensive tactical educations even to junior officers and non-commissioned officers.… Much later, the World War II German Gen. Hermann Balck would say: ‘We lived off a century-long tradition, which is that in a critical situation the subordinate with an understanding of the overall situation can act or react responsibly. We always placed great emphasis on the independent action of the subordinates, even in peacetime training.’12

As Balck’s cult status in the American military grew, the Army’s Staff College taught its students that his command of the 11th Panzer Division during the Chir River battles constituted the epitome of military excellence.13

Balck recorded his thoughts in a journal between 1914 and 1945, which formed the basis of his long-overdue memoir Order in Chaos, first published in English in 2015.14 The book reveals a thoroughly professional soldier and a deeply private man. Balck only hints at his domestic life and tells the reader nothing about his children until he encounters his son Friedrich-Wilhelm, a fellow soldier, in France in 1940. He then gives a purely military account on the burden of having offspring in one’s chain of command. Balck, true to his reserved natured, only mentioned his wife once in his memoir when reminiscing about their time together in Slovakia when he was on leave from the front in 1943.

Balck’s exploits have received the recognition they deserved within professional military circles and, over time, his battlefield success has also received significant attention in notable popular works such as Dennis Showalter’s Hitler’s Panzers, Peter McCarthy and Mike Syron’s Panzerkrieg and James Holland’s The War in the West. As historical memory of Balck has emerged from obscurity, the time is right for a wider audience to become acquainted with this remarkable leader of panzer troops.

HERMANN THE SOLDIER

Mathilde Balck gave birth to her son Hermann on 7 December 1893 in Danzig-Langfuhr in East Prussia. The Balck family came from Scandinavian roots, having migrated from Sweden to Finland in 1120, but after the Thirty Years’ War, his branch of the family settled in Germany along the lower Elbe River. Balck’s immediate ancestors had distinguished military careers; his great-grandfather migrated to England and served as an officer in the King’s German Legion and on Wellington’s staff during the Napoleonic Wars. Georg Balck, his grandfather, also moved to England and became an officer in the 93rd (Sutherland Highlanders) Regiment of Foot before losing his eyesight in the West Indies. The family practice of fighting for Britain ended during World War I when his father, Lieutenant General William Balck, commanded the German 51st Reserve Division, earning the Pour le Mérite (Blue Max), the Kaiser’s highest award for valour.

After Germany’s defeat, William Balck wrote Development of Tactics — World War, an authoritative account of Germany’s recent military experience, and the English translation became an American Army textbook. Balck recalled that his father ‘was the last great tactical theoretician of the Kaiser’s army’ who instilled in him ‘extensive military and general mentorship’.15 Balck’s remarkable father, more importantly, taught him to understand ordinary people and instilled in him a progressive social conscience:

I grew up and was educated as a soldier. But I also learned something else from my father, something even more significant — a deep sense and understanding for the lowest ranking troops and the mistakes of our social class.16

Balck, accordingly, developed a thorough understanding of his soldiers as people and led them with a strong sense of justice.

During World War I, the young Hermann Balck saw extensive action on the Western, Eastern, Italian and Balkan Fronts. In 1913, he became an officer candidate in the 10th Jäger (Light Infantry) Battalion based in Goslar, before attending the Hanoverian Military College in February 1914. Balck was promoted to second lieutenant as the guns of August raged. He first experienced combat while commanding a platoon from the 10th Jäger during the attack on the Liège fortress in Belgium on 8 August 1914:

In the town we encountered the first dead bodies of Belgian farmers, small people with grimacing faces full of anger and deadly fear. Cattle were running around without their masters. A few women squatted with the remnants of their belongings, staring with empty eyes. This was our first glimpse of war.17

Balck later fought the French and the British on the Western Front. During an engagement at Fontaine-au-Pire, he learned a valuable lesson which he applied throughout his military career: ‘A successful attack is less costly than a failed defense.’18 At Ypres, Balck personally experienced the brutal violence:

As shots rang out, the commander of 2nd Company, Captain Radtke, collapsed right next to me. He had been shot dead through the heart. I was hit in the left hip. I stumbled and fell right in front of the Englishman who had shot at me, and I was able to kill him with a pistol shot as he was rechambering his rifle.19

Before 1914 came to an end, Balck had become adjutant of the 10th Jäger and survived being shot in his right arm, left ear and back as well as suffering a grenade splinter in his hip. The army recognized his bravery, awarding him the Iron Crosses (1st Class and 2nd Class).

In 1915, Balck transferred to the 22nd Reserve Jäger Battalion and commanded its 4th Company in Poland, Serbia and Russia. During the brutal trench warfare near Pinsk, he learned another valuable lesson that would become the hallmark of his future command style:

Although things were quiet during the day, a lively war between the trenches began at night. The Russians used every trick in the book, including confusing us with German speakers and conducting silent ambushes from the rear. It was not always easy to keep our troops alert. They were innocently unsuspecting. I tried time and again to be in the right place when incidents happened, and often was able to prevent the worst.20

Balck, early in his military career, understood the need to be well forward with his men at the critical place to gain full situational awareness and exploit fleeting opportunities. He stayed with his company despite receiving shrapnel wounds in his right shoulder. After being given command of a Jagdkommando (special operations group) from the 5th Cavalry Division, Balck conducted raids behind Russian lines, including one patrol through the Rokitno swamps which lasted weeks.

In 1916, Balck returned to the 10th Jäger to command its machine gun company and, after leaving the Eastern Front, he fought in the mountains of Romania. As the war dragged on in 1917, he led his troops into battle in the Italian Alps as part of the division-sized Alpenkorps, where he survived bullet wounds to his chest, left arm and both hands. On another occasion, after an Italian machine gun propelled bullets into his chest and both arms, Balck returned to the front the next day with both arms in a sling.

In 1918, Balck successfully requested command of 4th Company of the 10th Jäger even though he knew the previous twelve company commanders had all been killed. He led the company in northern France, Macedonia, Serbia and Hungary. As the tide of war turned decisively against Germany and the spectre of revolution haunted the officers, Balck understood how to avoid the slide into the abyss:

Wherever the officers avoided the constant mass-produced mush, there was discontent; where the officers ate from the field kitchen, there was no sense of revolution…. No German soldier will turn against an officer who shares his joy and pain, death and danger.21

After shell splinters ripped into his hip and knee, Balck was awarded the Wound Badge in Gold and was recommended for the Pour le Mérite, but the war ended before he could be awarded the deserved medal.

After the armistice, as revolution in Germany ushered in the unstable Weimar Republic, Balck and the survivors of the 10th Jäger returned to Goslar where the local workers’ and soldiers’ council mandated the battalion elect a soldiers’ council. The troops unanimously elected Balck chairman of their council and, soon afterwards, the locals elected him head of the Goslar workers’ and soldiers’ committee.22 During this chaotic time, a grateful veteran declared to Balck, ‘I thank you, sir, in the name of all my comrades for everything you have done for our company.’23 Hans Falkenstein, a private from the 10th Jäger, shared this sentiment in a letter to Balck, ‘I participated with you as my company commander in the campaign in the West and in Serbia. I always like to remember you as a capable, courageous, and just leader.’24

As bloody frontier violence erupted between Germans and Poles, Balck and his unit, now renamed the Hanoverian Volunteer Jäger Battalion, fought in Poznań province during this savage ethnic conflict.

Although the Treaty of Versailles limited the Reichswehr to 4000 officers, Balck remained in the army, which is testimony to the faith the hierarchy placed in him as it only retained the very best officers. This small band of Reichswehr officers formed an elite cohort of exceptionally experienced leaders who saw themselves as heralds of a future army in a reborn Germany. The Reichswehr trained all its officers to accept higher levels of responsibility and to use their initiative to seize opportunities without the need to wait for orders. As these qualities were second nature to Balck, he thrived in the interwar army, becoming the adjutant of the 3rd Jäger Battalion.

In 1923, Balck transferred to the 18th Cavalry Regiment at Stuttgart to command its machine gun platoon. He swiftly rose through the ranks, being promoted to first lieutenant in 1924 and captain in 1929.

During the 1930s, Balck served in the 3rd Cavalry Division and commanded the 1st Bicycle Battalion. After serving as an exchange officer in the Swiss, Finnish and Hungarian armies, he twice turned down the opportunity to become a General Staff officer in preference to remaining a field officer:

I loved the frontline life, the direct contact with the soldiers and the horses, working with living beings, and the hands-on training with the troops. Becoming a second stringer, as so often happened in the General Staff, was not for me. Besides, as a member of the General Staff I could not have pursued the many diverse intellectual interests I enjoyed so much. Even my military interests, particularly military history, I was able to better pursue on my personal time. As a General Staff officer one too often was drowned in bureaucratic office work.25

Intellectual curiosity, self-motivated learning and a love of all things classical were core traits of Balck’s character. During World War I, he read from a complete works of Shakespeare between battles on the Eastern Front and he also immersed himself in Clausewitz’s On War: ‘Entertaining oneself during quiet periods on the battlefield by reading the great philosopher of war produced a strange sense of excitement.’26

When on leave from the front, Balck explored the great cities of Europe to admire their historical treasures and cultural life. ‘I drove to Warsaw,’ he recalled, ‘where I enjoyed the Russian emperor’s ballet dancers’ and ‘saw Puccini’s Tosca in Polish’.27 He often visited Budapest and ‘never missed the chance to go sightseeing in this uniquely beautiful city’.28 In Romania, Balck explored the Teutonic Order castle at Focşani to admire its architecture. He also possessed a deep love of antiquity and read his copy of Homer during the Greek campaign in 1941. Later in Italy in 1943, Balck modified his artillery plan to ensure that the Greek temples at Paestum remained outside the bombardment zone.

After being promoted to major in 1935, Balck commanded the 1st Bicycle Battalion in Tilsit before being promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1938. He next worked in Guderian’s Inspectorate of Mobile Troops in the Army High Command, where he helped craft tactical and doctrinal concepts for cavalry, motorized infantry and panzers. Balck remained in this position when the Wehrmacht invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, as Europe descended into another world war.

During the first month of World War II, Balck liaised with the panzer divisions to assist their reorganization and refitting following the Polish campaign while longing to again command troops at the front. The Wehrmacht obliged and gave him command of the 1st Motorized Rifle Regiment on 1 October 1939:

My assignment as the commander of the 1st Rifle Regiment in Weimar came as quite a relief for me. I would not have chosen any other regiment. In addition to the good reputation the regiment and its officers had, I had just outfitted this unit with the most modern equipment. Everything was armored and mobile. It was the most modern regiment in the army.29

This book is about the making of Hermann Balck as a panzer commander and explains his transformation into a master of tactical warfare during the French, Greek and Stalingrad campaigns. However, it is also the story of a remarkable leader who, as Freeman Dyson explained, ‘gaily jumped out of one tight squeeze into another, taking good care of his soldiers and never losing his sense of humor’.30

Balck commanded the 1st Motorized Rifle Regiment, within the 1st Panzer Division, during the French campaign in 1940. After crossing the Meuse River with his men, he created the decisive breakthrough at Sedan which allowed Guderian’s panzers to race to the English Channel and surround the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk, instigating the fall of France. Despite this remarkable victory, Balck analysed German tactical shortcomings and theorized a new way in which infantry and tanks would co-operate in battlegroups — the kampfgruppe concept — which revolutionized the way panzer divisions fought, allowing them to later achieve stunning success on the Eastern Front.

During the Greek campaign in April 1941, Balck commanded the 3rd Panzer Regiment and put his kampfgruppe ideas into practice. Balck’s innovative leadership enabled the panzers and infantry in his battlegroup to overcome seemingly impossible obstacles and secure victory against determined Australian and New Zealand soldiers, who defended the perilous roads and alpine passes near Mount Olympus. At Platamon Ridge on the Aegean coast, at the site of a medieval Frankish castle, Kampfgruppe Balck overran the New Zealand 21st Battalion in terrain the Allies considered unsuitable for tanks. The shattered New Zealanders regrouped in Tempe Gorge, the legendary home of Aristaeus, the son of Apollo and Cyrene, where they were reinforced by the Australian 2/2nd and 2/3rd Battalions. The Allied troops in the gorge hoped to stop Balck’s soldiers in ideal defensive terrain; however, the panzers of Kampfgruppe Balck rolled through the Allied lines and continued on the road to Athens.

Balck’s command of the 11th Panzer Division in southern Russia in 1942, during the summer offensive drive to the Don River and subsequent Stalingrad campaign, firmly established his place in history as a master of armoured warfare. At the Chir River, Balck fought a series of brutal engagements in the bleak Russian winter where he developed his ‘fire brigade’ tactics which were later used by the Wehrmacht to hold the Red Army at bay against impossible odds.

This book charts the critical period as Balck departed his infantry roots and first took command of an armoured unit, fully explaining his transformation into a uniquely gifted tactician — a journey which began in France.