In any production the editing is every bit as important as the shooting. In a professional world editing time can be very expensive, and most producers and directors will be strictly rationed as to how much time you are allowed to spend in the edit. The amount of time you would be allocated varies according to the type of programme and the type of budget allocated. However, it’s rare for anyone to feel that they have enough time; most people feel that they could always do with more editing time. In your project you may not be limited by financial considerations but you may have limited access to equipment and you may have limited time available. It therefore makes sense to try to prepare in advance as much as possible for your edit and make the most of the time you have.

As with cameras there are a huge variety of different types of editing packages, and systems change all the time. Therefore this chapter will not make reference to any particular type of equipment; however, it will assume that you have some access to a nonlinear digital editing system. While they vary slightly, most of them work in broadly the same way and whatever package you are using you will approach the edit in the same way.

Ingest

Ingesting is the process of loading your footage into the edit package so that you can start to edit. It’s a useful point at which to start to look at your rushes again and put them into some kind of order. Most edit packages use a system of files or ‘bins’ as they are often called to store your rushes.

How you order your rushes is up to you. Some people order the rushes by tape number or digital file. However, that means you have to have a comprehensive log of what is in which file and/or a good memory. Another way of dividing up the material is by subject matter. Each of your contributors could be in a different bin. You could have all your PTCs in one bin. The rest of your bins could be made up of material you intend for the different sequences. What you are really trying to do is order the material in such a way as to make it as quick and easy as possible to find the material again.

Time code

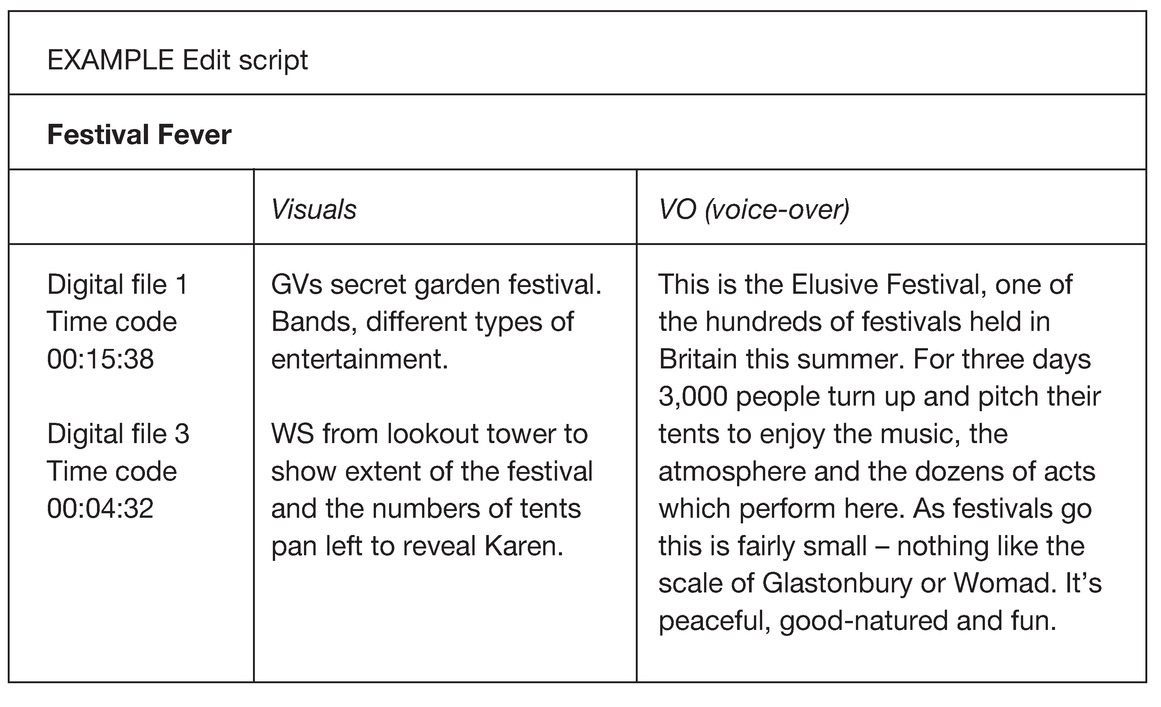

Most video cameras and most edit systems will give your shots a time code. This is usually an eight-digit number showing hours, minutes, seconds and frames. It will look something like 00: 03:13:32. The time code is important for locating your shots. By making a note of your time codes when you log your shots you will easily be able to find them when you start your edit.

Viewing and logging

It sounds obvious, but one of the most important things to do before the edit is to go back and watch what you have shot and make some notes for yourself. You can do this while you ingest the material.

Logging: When you log material you should make a note of three things:

- what the shot is

- what the time code is

- digital file or tape number.

The shot

In one sense this is fairly obvious; you will need to describe the shot; the size and any moves. However, you can also make other notes for yourself. If the shot is not usable, perhaps because something went wrong or because the camera wobbled, or any number of other things, then you can mark it as NG or no good. This will save time later; you may choose not to ingest these shots. It may be that you have taken the same shot several times. Each take was OK but may have had good and bad elements to it; you will need to make a note of how each shot differed. There may be something you particularly liked about a shot and know where you would like to use it. Again it’s useful to think about this. How you describe the shots and what notes you make will depend on you. Only you know why you like or don’t like a shot and how you think it might be useful.

Time code

Once you have identified the shots it’s useful to make a note of the digital file number or tape number and the time code. You can use this for reference when you start to make up your script. You can put the time code on your script so that you can easily find the shot when you come to the edit.

Digital file or tape number

Make a note for yourself of what is on each digital file or tape. This will save hours of needless searching. Viewing and logging rushes in this way may seem very laborious. However, it’s one of the best ways of becoming familiar with your material. By watching through the material and taking notes in this way the images will start to stick in your mind. Later on in the edit you will start to recall images and it will allow you to be a lot faster and more imaginative about trying out different shots.

Building your sequences

This is the fun bit and the most creative part of the editing. When you prepared your shooting script you identified the types of sequences you wanted to use and now is the time to start building them. Again, people vary in how they like to approach this. Some people start at the beginning of the script and work through, while others like to build up sequences out of order.

There are endless ways in which you can put shots together and there is no way to give you a rule book about this. However, here are some tips to help you get started:

- Think sequence, not shot: Individual shots strung together make for a very bitty edit. They don’t draw the viewer in. The viewers want you to tell them something with your choice of shots and thinking of sequences will help you to do this.

- Lead with pictures: Often when new directors start making programmes they plaster the whole thing with sync or commentary or dialogue. There is not a moment in the film when someone isn’t saying something. This can have a negative impact on the viewers who are struggling to keep up. They have to work quite hard to keep up processing all the images and keeping the narrative going. If you couple this with poor scripting then the viewers will struggle even more and their minds will soon start to wander onto something else and they will lose track completely. You should allow time throughout the film for the pictures to lead. You should lead into any commentary or dialogue with some pictures, giving the viewers time to settle before they start listening. You don’t necessarily have to come to a piece of dialogue or sync with the presenter or contributor in vision from the very first word. You can lay some pictures over the beginning and then come to them in vision.

- Jump cuts: The term jump cut can refer to cuts which don’t feel smooth, which slightly jar or disturb the viewer. Unless you are particularly going for that effect you should try to avoid them. The way to avoid a jump cut is never to cut together shots which are too similar. You should also avoid cutting from a wide shot to a closer shot without changing the angle of the camera. You should also avoid cutting from one wide shot to another wide shot without having something else in between; the viewers tend to expect a wide shot to be followed by a sequence of closer shots and if you don’t do this they will start to disconnect from the film.

- Establishing shots: You will need some kind of establishing shot for each different location you have visited. The establishing shot doesn’t have to be the first shot you use in any sequence but you will need to use it fairly early on.

- Reveals: Sometimes you will want to tease your viewers a little. You can start a sequence with something they don’t understand and then come to an establishing shot to reveal what the viewer is looking at. This can be an engaging way to start a sequence -just don't leave the viewer in the dark for too long!

- Length of shots: This obviously depends on the style of programme you are making. Some programmes have very quick fast cuts, others are more leisurely. Remember: the style of cutting needs to feel consistent with the subject matter of the film. If you are making a film about a very sensitive subject, for example, bereavement, and you use a very pacey style of editing and commentary, you can come across as being rather insensitive. On the other hand, slow moves and long shots on a piece can start to be a little boring. As a general rule, though, you wouldn’t hold a static shot for more than about five seconds unless there was a very particular reason for doing so, less than one second and it starts to be a bit subliminal. Where there is a move on a shot then it will hold a little longer. There are of course some programmes which don’t do this; they will use a very fast style of commentary. However, it’s difficult to sustain this approach for very long and it tends to be used for shorter sequences and to eate a particular effect.

- Cutting on a move: Previous chapters described types of shots including moving shots such as pans and tilts. It was suggested that you think carefully about these types of shots and only use them if you felt you had a good reason. The problem with moving shots is that it’s very difficult to get in and out of them when the camera is actually moving. You can get away with it sometimes but too much and the viewers will start to feel something a bit like motion sickness; it disturbs the brain a bit and they will get distracted and stop watching your film properly. You can of course cut in and out of the shot at the beginnings and ends of the moves when the camera is steady but if you have made your move too long you are left with a rather lengthy and possibly boring shot.

Effects

Even the most modest edit package usually comes with a number of effects. There are a huge variety of different effects you can add to a shot; the following are some of the most common.

Transitions

There are a number of ways of getting from one shot to the next:

- Cut: This is the most common form of transition where you have an instant change from one shot to the next.

- Mix/cross-fade/dissolve: These are all terms to describe the same transition, a gradual fade from one shot to another. They have a more relaxed feel than a cut and are useful if you want a meandering pace and contemplative mood.

- Fade: The picture fades to a single colour and then the next picture comes in. The colour is only on screen momentarily. The fade to black or fade from black are ubiquitous in film and TV and are used to signal the beginning and end of a scene.

These kinds of effects are similar to camera moves; you should use them sparingly and for a good reason. The different transitions subtly imply something to the viewer. If you use a fade to black it implies to the viewer that you have ended something. It doesn’t have to be the end of the film but it is definitely the end of a sequence. A dissolve or a cross-fade implies more of a connection, often between the images; sometimes it may imply a passage of time or move to a different place.

Wipes

One shot is progressively replaced by another shot in a geometric pattern. Pictures can slide on and off, either from side to side or up and down, they can pixelate, or peel on and off. If you experiment with your package then you will quickly get to see them. These can be great tools. However, they are defined effects and they will give your programme a very definite style. If you want to use this kind of effect you will need to use it consistently through the piece and establish your style quite early on. If you just use these effects once or twice through the piece they will start to jar and stick out like a sore thumb. This is not meant to imply that you should overuse the effects; just that you will need to establish the stylistic convention at the beginning of the piece and then stick with it.

- Slow motion and speeded-up motion: Most packages will allow you to speed up or slow down your shots. You can do this subtly so that it’s difficult to detect or you can do it very deliberately so that it’s obvious. Again if you do this there has to be a good reason and it needs to visually make sense to the viewer. Speeding up a shot is almost always done humorously; it’s usually because you want to indicate a passage of time. Slow motion gives a kind of dreamy effect, asking the viewers to think carefully about what they are watching. It gives an almost romantic implication. Be careful how you use it.

- Colour: Some packages will allow you to play with the colour of a shot. You can saturate the colour. This means you are putting more colour into the piece and gives it a very bright, vibrant feel. You can de-saturate; this means you take colour out of the piece and it gives it a rather washed-out effect. You can also change the reds, greens and blues individually to create effects. Like all these effects, you will need to be careful to use them consistently, rather than just throw in a few effects for the sake of it. You will need to have a good reason and the effect needs to be a part of the storytelling.

First assembly, rough cuts and fine cuts

Edits are normally divided into two phases: the first assembly/rough cut stage, and the fine cut stage.

- First assembly: This is a very loose assembly of the main building blocks onto a timeline. You will not have done much work on pictures at this point.

- Rough cuts: Once you have a first assembly you should start on the rough cut. You should start to put a shape to your piece adding in pictures, cutaways, etc. Once you have done a rough cut you should view the piece again and then make notes for yourself. Then you should go back and refine the piece a bit more. You can make as many rough cuts as you want but hopefully each cut will be a little less rough than the last. For this reason you shouldn’t spend too long getting all the fine editing right at this stage. It tends to be a bit of a waste of time, since you are likely to have to do it all over again as you change and refine the piece.

- Fine cut: The fine cut is the polishing stage. You should work on getting all the transitions right, getting all the sound levels right and making any fine adjustments to colours. You should only move on to this stage once you are happy that you have the piece as you want it.

Editing factual

Just as with shooting, the way you approach a factual edit is slightly different to the way you would approach a dramatised sequence. With a dramatised piece you will have a detailed script/storyboard which forms the basis of your edit. With a factual piece you should have your outline script but you will have to use the time between your shoot and the edit to make up your edit script.

Before the edit

Interviews

You will also need to review any interviews you have done. Sometimes interviews are transcribed; this means you have a written version of the interview. Transcribing can be very helpful: it offers a much more efficient way of putting your script together; it’s much easier to work from a paper version than from memory. However, transcribing an interview can be very time consuming and you may feel that it’s not worth it. If you decide not to transcribe the interview you will need to watch it through and make notes for yourself, just as you did for the shots. You can start to break the interview down into smaller sections; you can either break it down into the different answers or break it down by time. Either way you should be making a note for yourself as to which answers you felt were strong and why. If there are any bits you know you don’t want then again it’s useful to make a note for yourself about this.

Again, by looking at your interviews and making notes for yourself in this way, you will ensure that you become familiar with your material before the edit. The more familiar you are with the material the easier and quicker you can make decisions in the edit.

Preparing the edit script

Your next job is to start to prepare an editing script. For this you are going to need the outline script you prepared before the shoot and you will need all your notes from the log. In your outline treatment you will have a number of things to get you started:

- You will have already thought about the overall structure and narrative of the piece.

- You will have viewed all your rushes and made a note of important time codes.

- You will have an idea of where the interviewees and contributors fit in and what they are supposed to have said.

- You will have all the PTCs scripted.

- You will have a good idea of the type of information you will need in the links.

The edit script will look a little like your outline treatment. It should be divided into three columns, on one side the pictures and on the other side the words, and in the third column you will have a note of time codes so that you know where everything is and you can find it easily. However, now you will have all the pieces of the puzzle to hand and you can put in all the different elements.

The edit

First assembly and rough cut

People vary a lot in the way they approach an edit and you will find the way that suits you best. However, to start you off I’ll propose one method that you may find easy to adopt.

- Sync: These are your pieces of interview. Start the edit by pulling out the bits of interview you have chosen and put those in the timeline. You should be watching all the bits of interview. Often you will find that something that looks fine on paper sounds terrible and your sound edits won’t work at all. On the other hand, you may find that something you thought wasn’t that good turns out better than you thought. At this point don’t get too picky or do too much fine editing. You are likely to be moving things around a lot, so for the moment just pull things out and put them in the right order.

- PTCs: If you are using PTCs you should put them into place now. Don’t get hung up on finding cutaways or anything; just put them into the timeline as they are.

- Guide track: You will need to record your links as a guide track. Remember: this is not going to be your final commentary. Commentary tends to change all the time and it’s one of the last things you will put on. However, you will need some sort of guide commentary, your best guess at this point as to what the commentary will eventually be. Not everyone will do this. Some people prefer to build a sequence of images and then write the commentary. However, whichever way you do it you will be rewriting commentary a lot and at this point the guide track is really there to give you an idea of length and to indicate the sequences you are going to need.

- Build your roour rough cut: You can now start to build your sequence of images. Remember: you are looking for sequences not individual shots and you should be leading with your pictures.

- Timings: Once you have all the above in place it will give you an idea of the length of your piece. If you find that once you have laid down all the elements above your piece is much longer than this length then you should start to think about making some cuts now. You will save yourself a lot of time which you could spend cutting sequences tht just end up having to be junked for length. If you are under length then you will need to think about what more you should be be adding in. However, at this point you don’t need to have it exactly to length; once you start adding in your pictures it will begin to get much longer. Ideally, your piece shouldn’t be more than about 10 per cent longer than your ideal duration.

- Refine and recut: Go back over your cut to start refining. You may want to change the bits of interview or build up more pictures; you will probably want to change the commentary as your picture sequences build up.

- Feedback: Get feedback; you will need to hear a reaction to the piece from someone who doesn’t know it.

Commentary writing

Good commentary writing is a difficult task. Writing commentary for TV has a lot in common with writing for the ear in radio but it also differs. In radio the words help to create the picture but in television the words should be at the service of the pictures.

In the chapter on writing for the ear there was a discussion on ways to make your writing work for the ear and not the eye. If you haven’t read this section then you should do so before starting your commentary. There was also a discussion of the different types of commentary you might have to write. In TV there are the same basic types of commentary.

- Introduction: This is the section of commentary which sets up the piece and engages the viewer. It brings the viewers in and tells them why they should listen to the rest of the piece.

- Cues: A cue is mostly used in TV when the programme has a studio presenter. The cue from the presenter is the script which introduces the viewer either to a package, a kind of filmed insert to a studio programme or hands over to another presenter.

- Voice-over links: In a factual piece this type of commentary moves the story along. It will move us perhaps from one subject to the next or from one stage of the narrative to the next. It may lead from one interviee to the next.

- Authored commentary: Some programmes have a more ‘authored’ feel to them. Instead of an anonymous voice-over, there may be a presenter in vision who also does the links and the piece has a more personal feel. They may be an acknowledged expert in the subject or they may be undergoing some sort of personal experience. This type of programme may not have any interviewees but may be all scripted commentary. Natural history programmes tend to be done in this way.

In television you will need to balance the commentary with the pictures. Too little and the viewer won’t know what’s going on, too much and the viewer quickly gets a sense of information overload. Viewers can’t keep up with watching the images and listening to all the commentary; they will start to miss bits and lose the thread of what’s going on. The most skilful writers get this balance just right: they put the words at the service of the pictures, giving enough information but letting the pictures do most of the work. Like almost anything else, writing good commentary is subjective and creative, but here are some tips to help:

- Don’t describe what’s happening in the scene. If the viewer can see it you don’t need to spell it out.

- Don’t paint by numbers. You have put in your guide track, PTCs and sync but this does not mean that you have to literally interpret or illustrate everything exactly. You should be building the best sequence and then adjusting the commentary to fit the pictures, not the other way around.

- Don’t plaster commentary all over your piece. At the beginning of a sequence let the pictures establish themselves before you bring in any commentary; only say as much as you need to.

- Don’t let your commentary and pictures fight each other. While you don’t want to describe what is happening in a scene, at the same time you don’t want to be talking about something completely different, so that the viewer has to try to mentally make the two things fit together.

- Fix the picture: If it’s not immediately obvious what the viewers are looking at and why you will need to let them know quickly, otherwise they will be trying to figure it out and won’t be listening to your commentary. Even if it is obvious, you shouldn’t throw them off course by starting you sentence with something completely unconnected.

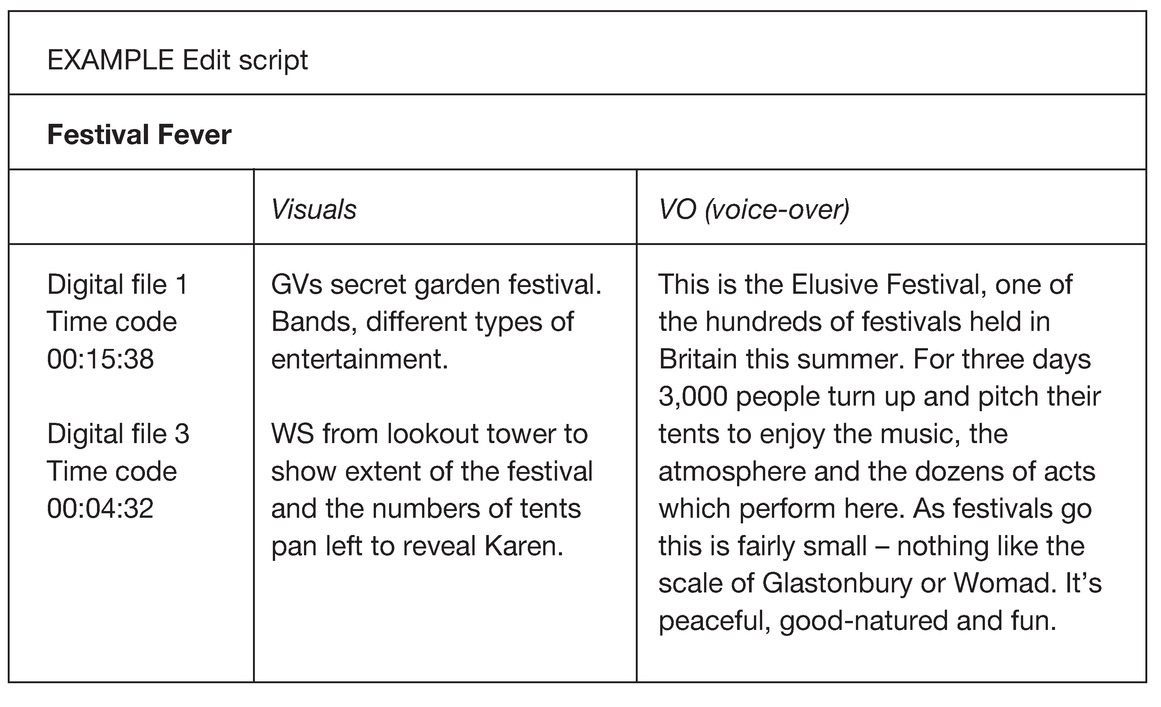

- Lead into picture sequences: It’s not always easy to do this, but if you can set up your commentary so that it leaves you an opportunity to follow with a sequence of shots without the need for more commentary, then you will find you have a stronger piece. Thus, for example, in the piece we looked at earlier on waste at festivals, you have decided to open your piece with some shots of the festival in full swing but you also want to talk about waste.

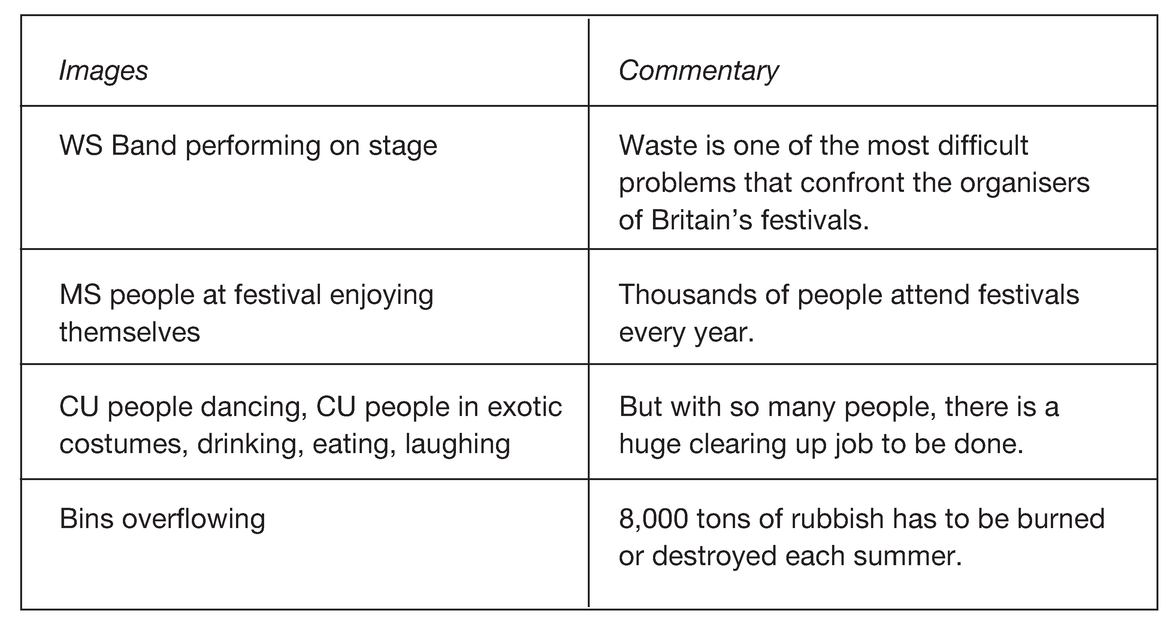

Example 1

In this example you will open the shots by looking at a festival, but the first word you use is ‘waste’. You have said ‘festival’ but right at the end of the sentence. The viewers are confused, not because they can’t recognise that they are looking at shots of a festival but you have opened your commentary with a completely unconnected word, and they will then start to wonder why.

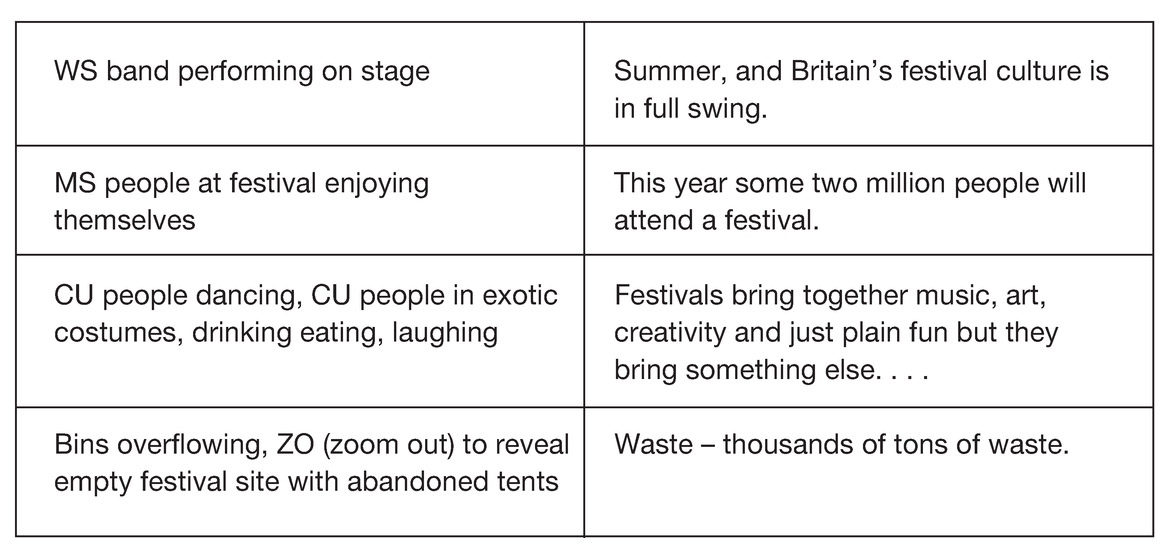

Example 2

The audience know what they are looking at and your opening words aren’t confusing them. The words full swing mean that at that point you could happily show shots of the festival without the need to say anything else. Again at the end, you have finished the link with the words thousands of tons of waste. The viewer will now happily watch any number of shots of rubbish and waste without you having to say anything else. Instead of telling a story with words, you are leaving space for the pictures to tell the story.

Laying commentary

Laying the final commentary is one of the last things you will do. This is because it’s likely to change any number of times during the edit process. However, once you have got your piece together you will probably want to re-record the final commentary and lay it. You may have been recording bits and pieces as you go along but if you re-record it all at the end and lay it fresh it will probably sound a lot better than lots of pieces recorded at lots of different times.

Music

Music in factual programmes is obviously determined by the type of factual programme it is. Some types of factual programmes have no music; the closer it is to a news programme the less likely it is to have music, which might seem a bit frivolous. However, other types of programmes will use music, either music recorded on location or music which is added later, sometimes both. Choice of music is obviously quite an individual thing; however, here are some hints:

- Music does significantly impact upon the mood or feel of your piece, so make sure you have chosen something appropriate.

- Generally speaking, music with lyrics isn’t going to work terribly well. The words of the song tend to clash with what’s happening on screen, unless they are specifically about the topic of the programme.

- Music with lyrics should never be used under commentary, as they will definitely ‘fight’.

- Music is like pictures and sound FX. The viewer needs some time to register the music, so always lead the music in advance of any commentary.

- You will need to dip the sound quite low under any commentary.

- As a general rule, it’s harder to make music work under interviews or PTCs

- Fighting rhythms: If you are using a lot of music you will need to make sure that the rhythm of the music isn’t fighting the rhythm of your cuts. If you have a slow piece of music with lots of very fast cuts it may start to feel a little odd and vice versa. Sometimes editors will try to cut the pictures with the beat of the music.

Laying music

Again, as you build your edit you can add music to see how you like it, but you should avoid doing any kind of fine tweaking of the music until you have finished the picture edit; otherwise you will find yourself having to do it all over again.

Editing dramatised sequences

In a dramatised sequence the process is slightly different. You will already have a script and if it’s a music video you will have a kind of script in that you have the song. However, just as with a factual programme you will want to make the pictures do the work. Just as with a factual programme you will need to look at your material before you start to edit so that you become familiar with it. As you ingest you can start to organise the rushes. Often directors and editors organise the shots according to the scene, the shot size and the character in the shot.

Let the pictures do the work: Just as with a factual programme you don’t want your entire piece to be dialogue from start to finish. You will need to allow space for pictures to do the work. You will need to build in time for this. It can be at the beginning or end of a scene, or during the scene if the dialogue can accommodate it, but don’t forget: building visual sequences is an important part of the process.

Continuity editing

In most conventional drama we tend not to notice the cuts very much; sometimes directors want the viewer to be very aware of the cuts but at other times they want the cuts to be barely noticeable. This kind of editing is known as continuity editing. If you want your cuts to be less noticeable there are some things you can do:

- Changing shot sizes: The least noticeable changes in shot size happen if you make the changes slowly. So you go from a wide shot to a mid-shot and then to a close-up.

- Changing angles: If you are moving from wide shot to mid-shot, you would normally choose a different camera angle. The angle should change by at least 30 degrees. If you use the same camera angle you get a jump cut, and this tends to disturb the viewer more.

- Match the shot sizes: If you have more than one character in a scene, once you have moved in from your wide shot to a mid-shot or close-up, you should try to keep the shot sizes and framing the same on both characters.

- Matching angles: If you want to preserve the sense of two people talking to one another you will need to have the correct corresponding angles. So when you make the cut the eye lines should match and appear to be looking at one another.

- Action cuts: An action cut is a cut which you make while a character is performing some sort of action. Thus, for example, your character may be reaching for a door handle. You may for some reason want to direct the viewer’s attention to the door handle so you may cut to a close-up on the door handle just as the character turns the knob. This kind of cut can be quite tricky to get right. If it’s a fraction out it will look a little odd to the viewer. Of course, it also depends on the shot having been right to start with. You will need to make sure that the action is at the same point in both shots when you make the cut. Editors will normally have both shots up on the screen at the same time and will adjust them more or less frame by frame to make sure they match.

- Crossing the line: Remember the crossing the line rule: nothing will disturb the viewer more quickly than if you start disrupting the geography of a scene.

Other points for drama editing

- Cutaways: These need to be motivated by the action or dialogue. If you use a cutaway, the viewer is going to assume that you have done so because you are trying to signal something or because you are sharing what the character is seeing/doing. If the cutaway has no purpose then the viewer will try to figure one out. Viewers will start to try to work out why you are showing them the cutaway and will become confused. While this is happening they are not listening to the rest of the scene and you will have lost their attention.

- Of course there are lots of directors who don’t keep to this pattern; they may deliberately choose to ignore it so as to create an effect on the viewers, possibly to remind them that they are watching a film, not real life.

- Pacing: Pacing refers to how long or short you make the shots between the cuts. Pacing your cuts really depends on the type of piece you are making. However, it’s worth remembering a couple of points.

- Static shots: Generally shots don’t last for more than about six or seven seconds before the viewer expects something else to happen. Shots which last for less than a couple of seconds can start to feel a little uncomfortable in a normal scene, it may feel somewhat jerky. Of course, lots of directors do use very short shots, particularly in a montage (lots of quick shots put together). However, the viewer cannot sustain this pace of shot change for very long.

- Moving shots: These tend to last a bit longer providing that there is a good reason for the move. Alternatively, if there is a lot gerf vement happening in front of the camera you can sustain the shot for longer.

- Speeding up the pace: If you speed up the pace of your cuts during a scene it creates a sense of urgency; it will start to feel as if some sort of climax is aboiece thappen. This is fine so long as it fits in with the narrative of your piece.

- Slowing down the pace: This has the opposite effect. If you have had some fast action demanding a lot of attention from the viewer, ch hen owing down the pace of the edit will allow the viewer some time to catch up.

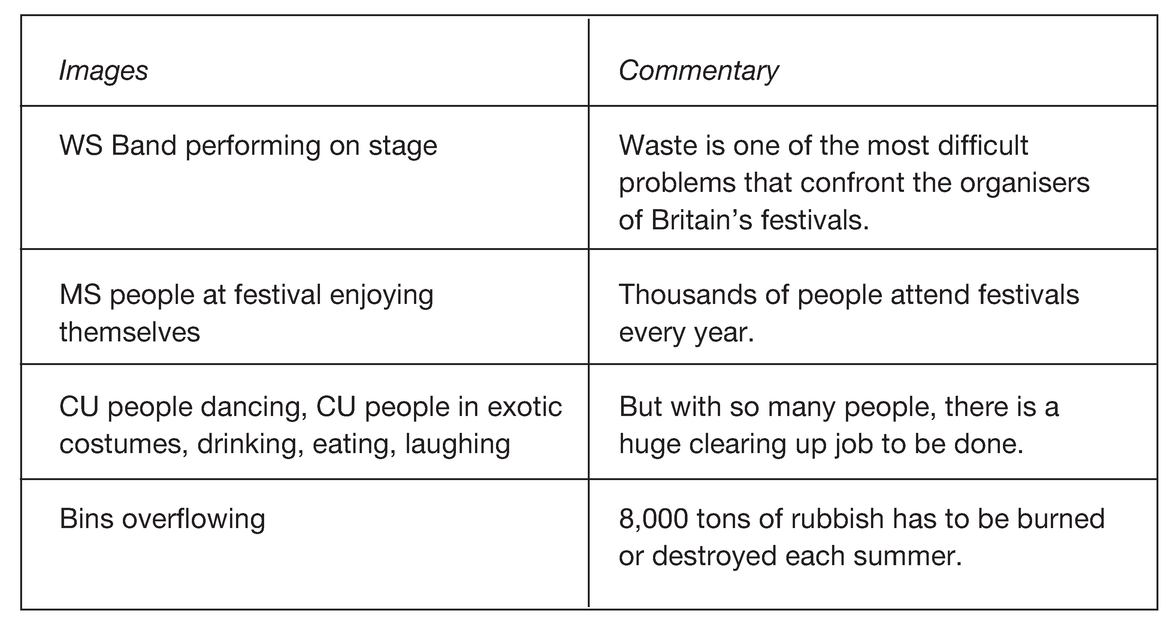

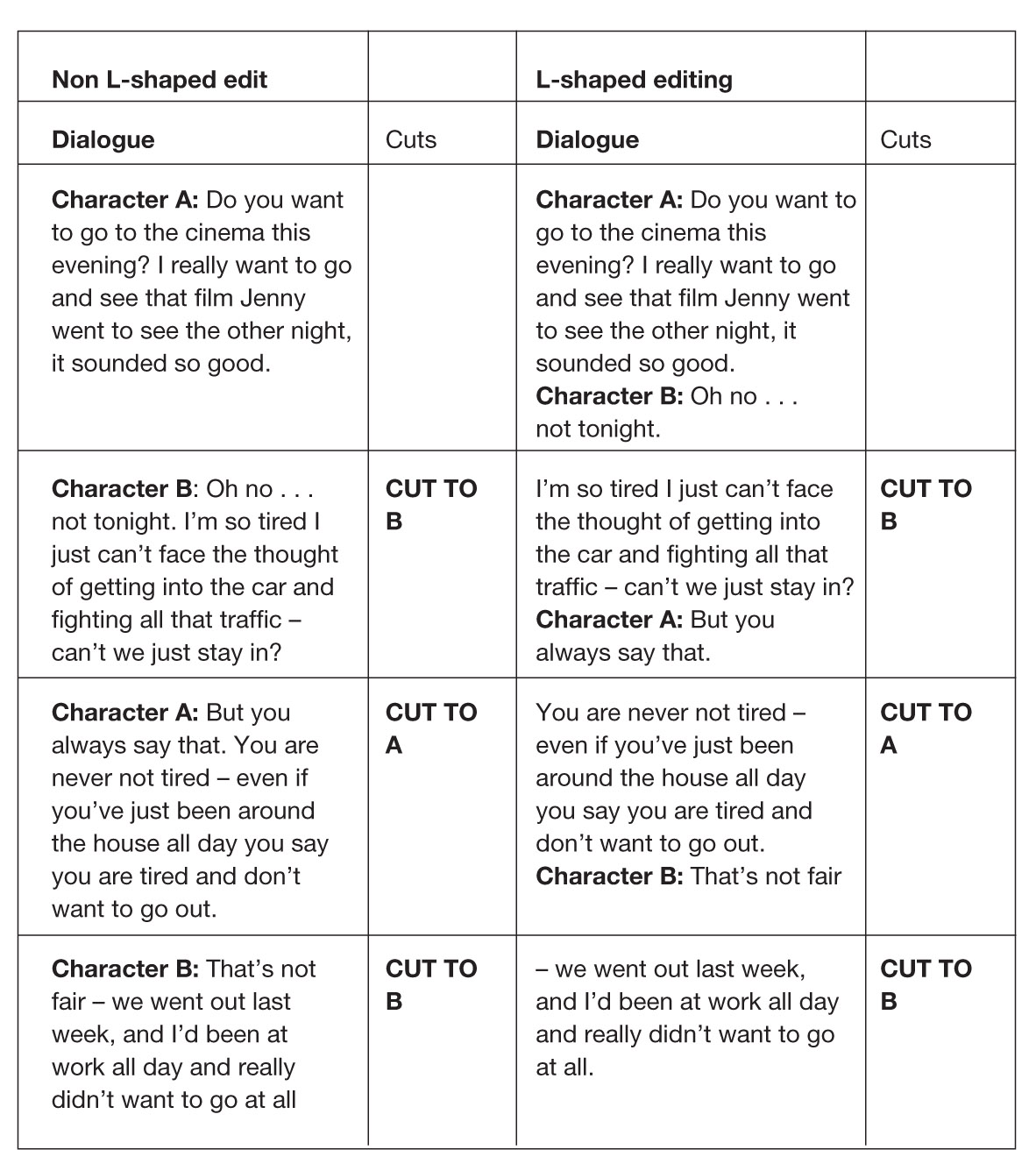

- Cutting dialogue: How you choose to cut your dialogue will significantly affect the quality of the finished product. Something may have been beautifully shot and acted but if the editing is poor the whole piece ends up looking quite shoddy. Here are a couple of tips to help:

- L-shaped editing: You don’t need to cut to the person speaking immediately as they start talking. It can often create a smoother edit if you allow the character to

say the first few words under another picture and then cut to the character. You can download the template off the website.

- 2. Reaction shots: If there is a long piece of dialogue from a character you may not want to keep the shot on the character who is speaking for the whole of the speech. You could cut to the person the character is speaking to for a reaction shot. You will get a sense of how the second character is reacting to the person who is talking. You can do this at a particularly dramatic point in the dialogue if it seems right. If you think back to the section on shooting drama, this is why you should run the scene a number of times and film reactions as well as dialogue.

Music

You may want to lay some music on your drama and this will play an important part in the edit. There will be two types of music you are likely to want to use; both of these will be added during the edit.

- Diegetic music: Music which is actually supposed to be a part of the scene, something the characters are supposed to be able to hear, something coming from a radio or CD, IPod, etc.

- Non-diegetic music/incidental music/title music: This is the type of music that the characters are not supposed to be hearing, which adds to the atmosphere of the piece. With this type of music you will need to make sure that the music is not fighting with the dialogue. Most of the time the music is either faded out under dialogue or kept very low so that it doesn’t detract. Music is more often used over sequences with no dialogue.

Music is generally one of the last things to be added. You should sort out all your picture cuts first and then lay the music. If you lay the music first you are almost certainly going to have to change it radically as you change the pictures, and you will waste a lot of time.

Music videos are slightly different. In this instance the music is the thing you are trying to feature, so you will probably find it easier to lay the music first and then cut the pictures to fit the music.

Trailers are a kind of hybrid. They are likely to use more music than the programme or film they are trailing. The music is often a way of holding the piece together. A trailer uses lots of different extracts from different parts of the film or TV programme, but having a single piece of music running underneath gives the piece cohesion and holds it together.

Voice-over/commentary

This isn’t often used in dramas, although you do sometimes get a kind of ‘narrator’ voice coming in. It’s commonly used if a story is told in flashback and you hear the voice of the person telling the story. It’s used quite sparingly, usually only at key moments in the drama. Trailers also sometimes use a voice-over commentary. As with factual programmes this is something you would lay properly at the end of the edit, although some directors will use a guide track or rough version of the commentary to help time the piece.

Fine cut

Once you have got all the pictures right, either for a documentary or a dramatised piece, and you are happy with the music and commentary, you can then move to finishing the piece off and doing the fine cut. This is the point where you will do any fine tweaking. You may want to adjust the sound levels and sound edits to make them smoother. You can add any effects or transitions you want to use. This process can be quite fiddly, so you will need to leave yourself enough time at the end to polish the piece. However, you will need to be sure that you are happy with the overall piece before you start this process. You can waste a lot of time if you start doing fine editing before you are settled on your rough cut.

The last process is the play out. You will have been given a format on which you are expected to deliver the piece, so you will need to ‘export’ the piece onto this format. Clearly you won’t want to play out your piece until you are absolutely sure that you have got the piece you want. Normally you would not delete the project from your edit package immediately. If there was some kind of disaster you might need to come back to it, but once you have played out then you have finished the actual production work.

Conclusion

The edit is a creative part of the production process; every bit as creative as the shoot itself. It’s important not to underestimate the amount of time you will need to spend on your edit. Just like the shoot, you will need to organise yourself if you are going to get the best out of your available time. It’s also really important to get feedback and to listen to the feedback: that first reaction to your piece is a really important one.