Many people think that “postproduction” begins a couple of days after the shoot ends, when your hangover from the wrap party has finally faded, and when you journey to the editing room to view—and be astonished by—the fruits of your last six or seven or eight weeks’ labor. Except for the hangover, that couldn’t be further from what happens. If a producer does his or her job properly, almost every element of so-called “post” has started mid- and even preproduction.

Not that you can ever eliminate surprises. If the editor has been working all along—and it’s pretty standard to have your editor working during production so that he or she can monitor sound and picture and give general feedback—you’ll already know how shots are cutting together. But you won’t know how whole scenes are cutting together. You won’t know how clearly the narrative is emerging, or how strongly the characters are coming through for an audience that hasn’t lived with them for months or years. The pacing might be slower or faster than you’d imagined, and elements of the plot that you thought were obvious might fly over people’s heads. Real knowledge of what you’ve got won’t come until you watch the first, rough assembly—or even the first test screening.

In some ways, a postproduction schedule is more iffy than a shooting schedule because, after eight weeks, if you’re not done cutting, you’re not done cutting. You can certainly set goals: x weeks for a rough cut, x for a fine cut, and so on. You should try to stick to your schedule. But if you screen your fine cut and the audience doesn’t have a clue what’s happening on screen, it’s back to the editing room. Post is a maddeningly inexact science, a profusion of Catch-22s: A lot of things can’t be decided until the movie is finished, but those things need to be decided in order to finish the movie.

Unexpected problems will arise: a scene doesn’t work, a lousy effect needs an optical, the sound is screwy, you realize you’re missing vital coverage, you get into a festival and suddenly have a new deadline for your mix and final print. Six weeks ago the special effects supervisor phoned the director at home in the middle of the night and got him to approve a new digital process that costs $20,000 and you’re only finding out now because the invoice just arrived…. Stay calm. Study the cost reports and think of possible savings. Brainstorm: “If we schedule a screening and invite everyone we know, then the editors will have to be finished to avoid a career-staining embarrassment.” “If five interns sell a pint of plasma each, we can afford an extra hour of mix time.” Stay on top of all the disparate elements and move forward, forward, always forward to that magical delivery date—which you will not make!

THE DAZE AFTER

Let’s catch our breath for a second and go back to the wrap. The day after production ends, you:

1. Sell off what you can, including the beer you didn’t drink at the wrap party, plus leftover stock, gels, Polaroid film, etc.

2. Return all equipment.

3. Make sure that all locations are restored to the satisfaction of their owners.

4. Inventory costumes and props, and arrange to store key ones for a period of time in case you need them for reshoots.

5. Conclude your contracts. Deal with all the unhappy vendors, people who are missing paychecks, etc. Make sure all production paperwork is complete.

It’s also time for the production accountant to tidy up the books and pass them on to the postproduction accountant, if you have one. On smaller films, which don’t involve that much accounting, your postproduction supervisor can often handle the books. But as the movies get bigger, the variety of expenses gets mind-boggling. You’ll have a payroll for sound and picture departments, optical vendors, labs, and sound houses, along with bills for shipping, vehicle rentals, and reshoots. Plus there’re all the bills from production that, like ol’ man river, just keep rolling along. If you can afford one, hire a separate postproduction accountant. If nothing else, he or she will act as a check against a profligate post supervisor, earning his or her salary back and then some.

A postproduction office is different from a production office: fewer people, a lot quieter. But it’s hardly pressure-free. If your movie has been financed by someone else, then there’s usually a delivery date in your contract. And, if you’re smart, that date will allow for every possible disaster. On Safe, a couple of cans of negative were never developed, and when I called the lab they had no record. All the negative film for a crucial scene was in those cans, and our only recourse was to get the missing takes from a work print that had been pawed and scratched and mangled for twenty weeks. I debated calling Todd, but he was in the middle of the sound mix, and I feared he’d throw himself off the Williamsburg Bridge, so I went back to the schedule to see when the scene was shot: Ah ha! Right after the major earthquake that had shaken LA, when the lab had been in (understandable) disarray. Knowing that helped me get through the next excruciating twenty-four hours; I figured if ever there were a time for reels to be misplaced (as opposed to lost), it would be just after a six-point temblor.

After a day, the reels turned up, and Todd and I had a good laugh.

MAKING THE CUT

An editor from the first hundred years of moviemaking would not recognize the inside of an editing room as it has come to look in the last five. People still occasionally edit on film: They cut frames and tape (splice) them back together; to make changes they have to pull off old tape, and put on new tape; and they have to keep their bits and pieces (“trims”) in order in case they need them. When I was an assistant editor I spent most of my time organizing trims and looking for missing ones.

What has changed the face of editing is the advent of the immense, nonlinear Macintosh-based system called Avid—a system that allows you to use “telecines” that are digitally transferred to a computer. (Another computerized system is called Lightworks.) This means no more film bins, editing tapes, or splicers.

The process is supposed to be faster on an Avid but, in my experience, that isn’t the case. The fact that you have more options when you edit on video can slow you down. Making a change on film is a commitment: You pull things apart, cut off frames, resynchronize everything—your editor can spend at least fifteen or twenty minutes just moving shots around. On an Avid, you do all that with the push of a button. You don’t have to commit so quickly: You can save the sequence the way you had it, try it a new way, try it a completely different way and save that, and then go back and watch all three ways. By the time you’re done fussing around, you’ve put in the same number of hours as you did in the days of Steenbeck tables and yards of loose celluloid. (Writers I know say that the same thing is true for writing on a word processor versus a typewriter.)

Another Avid frustration: The computere opens the door to expensive possibilities that you probably can’t afford. You can put in just about any fancy optical you want: cross-fades, superimpositions, wipes, split screens. The problem comes when you transfer them to film. A lab will do certain standard dissolves for free, because its machines are already calibrated, but for extras you’ll pay dearly. So every time the director and editor add an optical effect on the Avid, your costs go up. Keep tabs on them, or they’ll bankrupt you.

Actors invariably complain about scenes that have been left on the cutting-room floor, but most performances are improved, not weakened, by editing; I’ve heard of stars whose careers were saved because of what never saw daylight. On almost every one of the films I’ve produced, we’ve been concerned about an actor in dailies, but have been able to cut together a strong performance. This isn’t theater acting. Many performances don’t take hold until you see them cut together. Good directors will ask for different kinds of readings, so that they’ll have more choices in the editing room; when you pair together master take three and close-up take two, something amazing can emerge. (One thing you’ll hear directors and editors complain about is actors who “can only do it one way.”) Editing can’t make a bad performance (or a bad movie) great, but it can make it much more watchable.

JAMES LYONS, editor

My role as editor on Velvet Goldmine really began when Todd Haynes and I first conceived of the film. Knowing that the plot would cover many characters over a great period of time, that musical sequences would be at its heart, and that much of the story would be told in a series of flashbacks, forced us to make strong editing choices in order to write the script. With each draft we debated questions that can be seen as editing questions: How to reveal narrative information and when to withhold it? Which actions needed to take place over the course of a scene and which could be abbreviated in a montage? Where would musical performances increase the emotional intensity of the movie rather than stop it dead? Many decisions that on a film with more money would have been made in the editing room, had to be made ahead of time. I don’t recommend this to most filmmakers. Todd Haynes has amazing skills of pre-visualization and can hold immense amounts of information in his head. He knows what he absolutely has to have to make a scene work, what’s worth going the extra mile to get, and what can be omitted. Without these skills the film would never have come together. As it was, I think, everyone—Todd included—was crossing their fingers a bit.

My first official actions as editor were to attend Todd and director of photography Maryse Alberti’s storyboard meetings. Having the editor at storyboarding is, I think, crucial, but is not done often enough. On Velvet Goldmine we needed to have a full assembly of the film three weeks after principal photography was completed. This meant I would be cutting scenes while Todd was shooting them, with very little access to him. Without this time together before production began, it would have been impossible to know what he and Maryse had in mind.

Storyboarding is one of the nicest parts of the filmmaking process. Our work was simply to dream: What would be the most elegant, compelling, and beautiful images with which to render the ideas in the script? Todd would come in with sketches and notes and explain what he wanted and Maryse would say. “That’s possible,” or “We’d need other equipment; what about this?” The money at this point is all in your head.

It’s the editor’s job to think about coverage, and mistakes at this stage can have a very high price. Without that shot of the murderous feet walking slowly down the stairs, it’s impossible to build suspense. Inexperienced directors are often drawn to shooting important dramatic scenes in a single continuous take—a “macho” style that leaves no way of changing pacing or helping unsteady performances.

During production, the editing room is the first line of defense. Mark (my British assistant) and I would look at everything as quickly as possible to make sure it was exposed and developed correctly. After that, you look at the performances: Are they working together? Actors can have very disparate styles. You have to cut scenes to know if they feel like they are in the same movie.

Working on performance is my favorite part of editing. The key to its looking hard at what the actor actually did in front of the camera and leaving aside what you hoped they’d do or expected them to do. Once you understand what they brought to that moment and how it makes you feel, you can use it in the larger structure of the film. Jonathan Rhys-Myers brought a warmer, youthful quality to the part of Brian that I never expected. This tempers Brian’s cold, calculated side and makes him more human. Christian Bale has an uncanny ability to register subtle shifts of emotion without speaking a line. As Arthur he spends most of the film listening to Cecil and Mandy tell their stories while he remembers his youth. Without this faculty, his character would have been lost; with it, he takes his rightful place as the emotional center of the film. As we watch him listen, we see how much what he’s hearing makes him feel. First, we are intrigued, then, as we learn more about him, moved.

In contrast, Toni Collette as Mandy carries off grand gestures and sudden changes of emotion with great accuracy and grace. Velvet Goldmine itself walks a tightrope between these two poles—the glory of the extravagant gestures and the deep intimate feelings that make such gestures necessary. Toni and Christian played off each other wonderfully, so wonderfully in fact that our first cuts of their scenes together were much too long. We cut them back considerably.

You have to be rigorous and, sometimes, ruthless even with the stuff you love the most. The musical sequences were another case. At first we tried extending the songs to include all the great material we had shot. This proved deadly. Those sequences had to be fast and colorful and fleeting—like dreams you can’t quite remember. They had to embody the exuberance of youth recalled from the compromises of adulthood.

Perhaps the hardest part of cutting a film is trying to imagine what it would be like to see it for the first time after seeing it yourself 500 times. Screening it for other people, especially those not in the film industry, is invaluable. Velvet Goldmine is so complicated that people often had a hard time explaining where they were confused or lost. Here again we had to leave aside our ideas about how the script was supposed to work and learn how it did work. Only then did we ahve a chance of making good on the dreams we dreamt in the very beginning.

THE FURY AND THE SOUND

Now it should all go like clockwork:

- From the Avid, the editor prints an Edit Decision List (EDL), which gives you the selected shots and their corresponding key codes on the negative.

- The negative cutter pulls relevant sections of the negative and sends them to the lab. (The negative cutter does not yet cut the negative, which is a Big Deal; he or she only finds the takes the director has chosen so that the lab can make a print.)

- The lab produces a “one-light print” of all the takes—the cheapest and fastest you can get, with no adjustment of light levels or color correction.

- The one-light is sent to a “conform” assistant, who splices it all together.

- A “work print conform” is struck, and everyone gathers to see how everything looks on celluloid. Although very low-budget movies skip this step (we didn’t do it on Kiss Me, Guido), it’s a good idea to check out what you have before you commit to cutting the negative. The Avid hides fine details, and shots that work on the video might look horrifying on film. Say hello to boom shadows, reflections of hapless crew members in mirrors, and focus problems that were minimal on the Avid. Sometimes the technology will allow you to reframe a shot or blow up a small detail, but a lot of times with a low budget you just have to go to another take or live with your gaffes and hope that no one will notice.

As you’re putting together your picture, you’re trying to find a sound team and arranging the dates for your mix.

If you haven’t hired a composer, you’re searching for one. Every day, more kids graduate from music school who’d kill to be the next Danny Elfman, Carter Burwell, or Michael Kamen, and you can get them cheaply. If you’ve got a really terrific movie, you might even get Carter Burwell or Michael Kamen, as we did on Velvet Goldmine and Stonewall, respectively.

Do you have a distributor? If not, now’s the time to think about how and when to initiate a Close Encounter with an acquisitions person, a process discussed at length in Chapter 9. How soon you attempt this might depend on how desperate you are for money to finish postproduction.

Meanwhile, your music supervisor is trying to get songs that your director wants to cut in, and the cost of those songs will be a rude awakening. You’re trying to decide if you can afford a particular number while the music supervisor hunts for cheaper alternatives—but quickly, because many directors in the post-MTV generation like to edit to the music. There are publishing (synchronization) fees and master fees. If someone in your film sings a copyrighted song, you have to pay a publishing fee, which goes to the composer. If you use an existing performance, you have to pay a synchronization fee and a master fee, which goes to the performer. A lot of directors edit to temporary music and get very attached to it, so the earlier they can start playing with the music they’re going to use, the easier a time—creatively and emotionally—they’re going to have.

You can’t start your sound editors until you’re pretty close to locking the picture, because if they edit to an unlocked picture, they’ll need to go back and redo it all. That’s a common screwup in post. Your sound person finishes an intricate collage and then you suddenly realize that the scene needs to be two seconds longer or shorter—and everyone goes nuts. You take a lot of risks doing a digital mix to a videotape instead of a film; once you cut the negative, you might find yourself with unsalvageable sync problems. (On Guido, we never could figure out why ten frames were out of sync, but we had to remix to fix the mistake.)

Once the editor locks the picture, the director and the supervising sound editor sit down and watch the movie and make the big decisions about sound, music, and dialogue. Should the composer lay down some violins over the love scene, or will the couple’s heavy breathing be enough? Do you want silence when the heroine opens the door to the attic, or doom-laden music, or just the echo of her footsteps and the creeeak of the door? The last you achieve with “Foley,” which covers, say, footsteps or doors closing or the rustle of clothes. The effects are created in a Foley studio, which is filled with myriad surfaces for walking and running and door-slamming, and where Foley technicians watch the movie and stomp around in heavy boots or stab cabbages to simulate someone being knifed. Some directors hate Foley because every single movement has a huuuge effect. And it’s true that once you’ve used it, you’ll register the artificiality in every movie you see. But you often need Foleys to get a clean sound effect.

You’ll also be creating an ADR (additional dialogue recording) track, which includes the “looping” of dialogue and the addition of voiceovers. ADR can cover for problems you had while shooting. If a car alarm was blasting nearby, and you couldn’t wait for it to stop because you were in danger of losing the light, someone had to make the decision to go ahead and shoot and “ADR it” later. (The common expression is: “We’ll fix it in the mix,” and sound editors are always cursing you for passing the buck.)

Often directors use ADR as a last-ditch tool for improving (or saving) performances. You can correct a lapsed accent or a wrong inflection. The only problem is that some actors are terrible at it. Others have difficulty getting back in touch with their characters. Jared Harris underwent an astonishing transformation to play Andy Warhol, and he had a hard time reviving Warhol for ADR months later. To play Arthur in Velvet Goldmine, Christian Bale developed a “Mancunian” (Manchester) accent which he’d forgotten by the time we did ADR. Brad Simpson, our postproduction supervisor, brought him a tape of himself a couple of days before the session so he could practice his Arthur again. Another factor in scheduling ADR is that your actors might have scattered to all parts of the globe. In the best of all worlds you want to have everyone together, but you often end up recording people in different places. When it came time to do ADR for Velvet Goldmine:

Toni Collette was in Australia.

Ewan McGregor was filming in a small town in the north of England.

Jonathan Rhys-Myers was in Dublin.

Christian Bale was in Los Angeles.

Eddie Izzard was on tour in Paris and New York.

Meanwhile, our contingency had dwindled to almost nothing. We had to delay some of the voiceover, squeeze in Ewan and Jonathan, drop Eddie Izzard from ADR (we made do with his existing production tracks), and wait a month to get Toni and Christian when they were both going to be in Los Angeles. We also had to pay for Todd Haynes’ travel to three different ADR studios.

You add texture to a film with background voices, but you often don’t know what you’ll need in terms of crowd reactions until you’ve cut everything together. Velvet Goldmine posed a lot of problems in this regard. For one thing, it was shot in England and edited in the United States. The background voices—say, to fill up a pub—had to be English, and although a bunch of us Yanks could have stood in front of a microphone and bellowed things like, “Blimey! Give us another pint then!” we thought it more prudent to fly Todd Haynes and the ADR person back to England to record the real thing. (Todd did put on an English accent and record himself for a “scratch” track, which accompanied rough-cut screenings of the movie.) For a scene outside the Lyceum Theatre, where an actor playing a BBC reporter was doing a news story on Brian Slade, we wanted to hear the reporter without a lot of background yelling, so we had to go back to London to record the crowd later. Yes, we could have done it after we shot the scene (and we did record the concert audience going crazy for Ewan McGregor as Curt Wild after we’d dismissed Ewan for the day), but it’s hard to get into a sound recording mindset when you’re shooting. Who wants to spend three hours recording additional dialogue for a scene that might not make it into the movie?

Once you’ve recorded and edited your sound, it’s time for your premix and mix, which is always an expensive process. First you hire a sound house that provides the equipment and the personnel. Low-budget films will often go “standby,” which means you’ll wait until the people mixing the Bruce Willis movie are done for the night and then move in and work until morning. This saves a lot of money. Another cost-cutting technique is allowing the sound house to break in a new mixer on your film. Go Fish was one of mixer David Novak’s first features, and now he’s a big deal. (He just finished mixing Velvet Goldmine.)

At the mixing house, the mixer takes all your disparate, edited sound elements—ADR, Foley, voiceovers, crowd noises, music—and makes them work together. After a premix, at which temporary levels are set, the mixer goes through the movie reel by reel in excruciating detail. It’s a surreal vision, an anarchic muddle of blinking lights, levers, and flashing buttons. The mixer sits in a rolling chair and glides left and right along the length of a master console that looks like something you’d find on George Lucas’ Death Star, moving his or her hands across the board like a pianistic fighter pilot—listening, watching, adjusting levels. Lay folk who visit the mix think it’s cool to see how the sound comes together—but by the second hour of hearing the same line of dialogue over and over and over again with subtle changes, they’re pulling their hair out. The mix takes virtuosity and patience.

You’ll have a lot of decisions to make. Do you want to use Dolby? (You’ll need to pay a license fee.) Digital or analog? Foreign distributors generally insist on a separate Music and Effects (M&E) track, which allows a foreign distributor to drop in German or Italian or Japanese voices without losing any texture. Then your sound house films the optical track, which goes to the lab and gets laid down—it looks like scratches on the side of the film—on your final prints.

The final negative cutting takes a long time, sometimes a month or two. You insert all the opticals; watch an answer print, which is the first print off the negative and is scrutinized especially closely for light levels by the cinematographer; correct for color and sound; strike an “interpositive” and an “internegative”—the latter a sturdy negative that’s used to make your scores (hundreds? thousands?) of exhibition prints; and open a bottle of the best champagne you can afford.

When you deliver a movie to a distributor, you’re expected to provide them with copies of the shooting script and all your contracts and music licenses. The latter might take years to finalize, though. I was in Ted Hope’s office at Good Machine recently and in walked someone with a draft of the final soundtrack deal for The Brothers McMullen—a film that was released more than two years earlier.

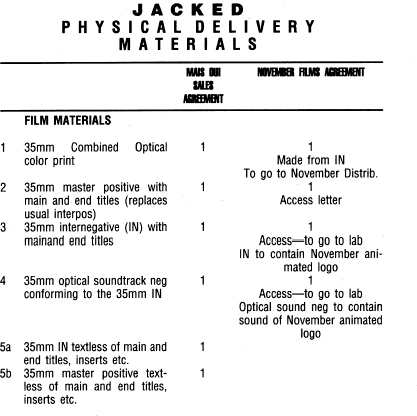

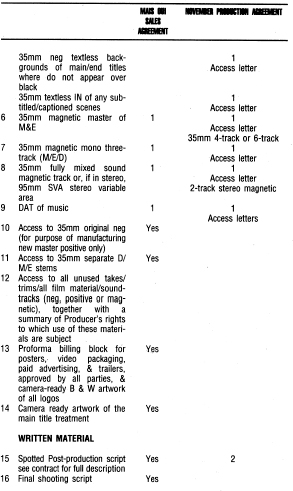

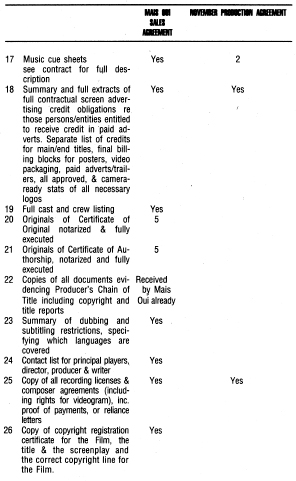

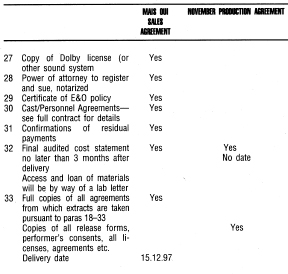

A distributor will give you a long list of “deliverables”—and you’d better deliver them. (See the typical deliverable list below.) One missing element and you’re technically in breach of contract, which means that the distributor can refuse to pay you. If they’re not pleased with your movie, you’ve just given them an easy way out of the deal. So deliver.

Testing One Two Three

Studios test movies early to get John Q. Public’s feeling about, say, whether it’s okay to kill off an actor or if an ending is too much of a bummer. Independent filmmakers, on the other hand, are supposed to operate differently—to stay true to the director’s vision, to lead the audience instead of following its dictates. But that’s no excuse for arrogance: You should always listen to what objective viewers have to say. We routinely screen our movies for people who haven’t read the script or been involved in the process, especially when a film of ours consciously sets out to experiment with narrative language. In the case of Velvet Goldmine, we expected there to be moments when the audience was off balance, but we wanted to be in control of those moments. It’s a tough call: When are you tantalizing your viewers and when are you pissing them off?

As soon as he finished a rough cut of Velvet Goldmine, Todd Haynes held a screening on high-definition video for close friends and colleagues, and afterwards passed out a questionnaire that was as challenging as some of the final exams I took in college. People sat hunched with their pencils poised, struggling to answer probing questions about the plot, themes, and pacing—and it wasn’t multiple choice! Ultimately, Todd and his editor, James Lyons, learned a lot about what was and wasn’t coming through onscreen.

What Todd doesn’t like about standard questionnaires (I’ve included an example in chapter 9) is what I like about them: They’re not too leading. If you ask a question like, “What would you say, in terms of pacing, was the slowest part of the film for you?” you’re planting the idea that parts of the film are slow. And so your viewers will write: “Well, actually, now that you mention it…”

It’s a shock seeing your movie with people who haven’t seen it before. You know when their attention is starting to wander. Things you think are totally obvious turn out to be incomprehensible. Major characters get mixed up in people’s minds. We knew we were in trouble with Swoon when the audience couldn’t tell the difference between Leopold and Loeb—we had to put in voiceovers to distinguish them. In Velvet Goldmine, the audience had no idea who Shannon, Brian Slade’s increasingly formidable assistant, was—her style changed so radically from scene to scene that they didn’t recognize her. We had to hold on her longer in certain shots, and to reshoot some footage to emphasize her more. Americans were also confused by Toni Collette’s accent, which is English in the London scenes and American when the action shifts to New York, more than a decade later. The British got it instantly, because they see so many Americans who move to England and suddenly start vocalizing like Henry Higgins. But to clarify the character—and to protect Toni from unfair criticism—we had to insert a line explaining that she’s an American living in Britain and affecting an accent.

You have to read between the lines, because people don’t tend to be articulate, especially right after they’ve seen the movie. A scene that they think isn’t working might have nothing wrong with it: It might not be working because the section before it didn’t work, and so they didn’t know what was going on. In that case, the solution might not be to get rid of the scene but to tighten up what’s around it.

It’s important not to be defensive, especially if you’re making a film that takes risks. Not everyone is going to like it, nor should they be expected to. You can’t expect to please all of the people all of the time, unless you’re a mogul with a hundred million dollars on the line—which is the best reason of all to stay independent.